Abstract

Background

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is frequently discontinued after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation, which could increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). Few studies have attempted to improve DAPT adherence through web-based social media.

Objective

To explore the effect of social media on DAPT adherence following DES implantation.

Methods/design

The WeChat trial is a multicentre, single-blind, randomised study (1:1). It will recruit 760 patients with DES who require 12 months of DAPT. The control group will only receive usual care and general educational messages on medical knowledge. The intervention group will receive a personalised intervention, including interactive responses and medication and follow-up reminders beyond the general educational messages. The primary endpoint will be the discontinuation rate which is defined as the cessation of any dual antiplatelet drug owing to the participants’ discretion within 1 year of DES implantation. The secondary endpoints will include medication adherence and MACEs. Both groups will receive messages or reminders four times a week with follow-ups over 12 months.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was granted by Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (GDREC2018327H). Results will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and presentations at international conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: mobile health, discontinuation rate, dual antiplatelet therapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This multicentre trial will first provide comprehensive evidence of the effectiveness of social media on drug compliance with dual antiplatelet therapy and health management.

Interactive response based on behavioural change theory will offer a new approach for motivating patient stickiness and obtaining patient feedback.

The distribution of people older than 65 years may be limited because the study requires the use of smartphones.

The causes of discontinuation of either drug, such as drug changes, gastrointestinal reactions and allergies to aspirin, could not be collected and classified.

Introduction

With an ageing population and the increasing prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, the disease load of coronary heart disease (CHD) will grow dramatically in the future.1 2 Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is generally recommended after patients’ drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation to reduce cardiac events.3 Despite conclusive evidence on the effectiveness of DAPT demonstrated in previous studies,4 5 approximately 9.8% of patients discontinue antiplatelet therapy themselves during the 1-year follow-up period, and the overall discontinuation rate is as high as 23.3%6 in the USA and Europe. The discontinuation in 1 year is higher than that in the short duration. The incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), stent thrombosis and target vessel revascularisation was significantly increased in patients with DAPT cessation due to poor adherence.6 7 Many studies have demonstrated that improving medication adherence is of great significance for the long-term prognosis of patients with cardiovascular diseases.8 9

Mobile health offers new and low-cost approaches for improving patient management of chronic diseases.10 11 Previous studies have proven that interventions, such as patient education, counselling and medication reminders, can improve patients’ medication adherence as well as outcomes.12 13 However, only several studies have focused on improving patients’ DAPT adherence via social media, especially the popolar application WeChat. Therefore, we designed this multicentre, single-blind, randomised study to explore the prevalence of DAPT discontinuation and the effect of social media on DAPT adherence among patients who need 1 year of DAPT following their DES implantation.

Methods

Study design

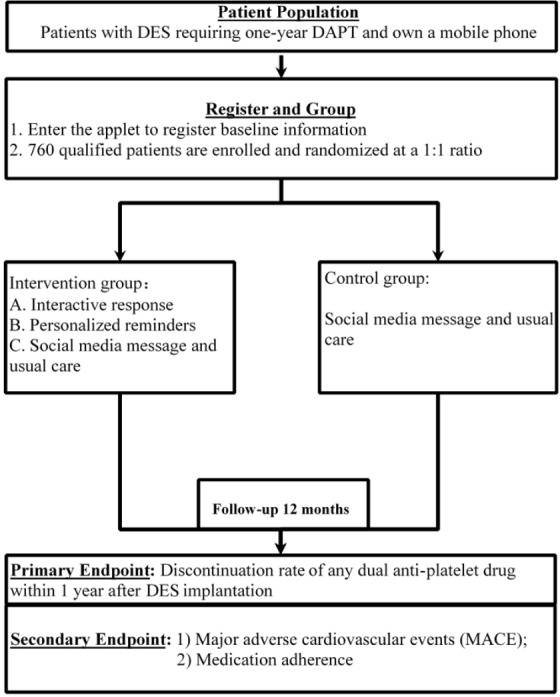

This WeChat study is a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial that will include five public hospitals as recruitment sites in Guangdong Province. Participants will be allocated randomly to two arms: the intervention group and the control group. The control group will receive messages four times a week only, while the intervention group will receive interactive responses, medication reminders, medical knowledge education and follow-up reminders, in addition to messages. Blinding will be maintained during the entire study (figure 1). Trained research nurses will conduct the follow-ups after 6 and 12 months by telephone or in face-to-face visits. All adverse events will be collected in the self-reported section of the mobile health tool or by the investigators.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study design. DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DES, drug-eluting stent.

Data collection

Patients in both groups will be required to provide baseline information, including social demographic characteristics, history of diseases and social behavioural characteristics, such as smoking status and sports activity. They will also be required to use WeChat as soon as they are enrolled in the study. Medication adherence will be evaluated by the proportion of days covered (PDC) at both 6-month and 12-month visits.

Study population

Participants will meet the following inclusion criteria:

Patients aged ≥18 years undergoing DES implantation within 7 days of recruitment.

Participating patients are required to receive a recommendation to undergo DAPT for at least 1 year after their doctor’s evaluation. Participants with a confirmed diagnosis of acute coronary syndrom (ACS) will be eligible for the study. The duration of DAPT will be evaluated by Precise-DAPT scores and in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). Those who are recommended to have 12 months of DAPT will also be considered for inclusion.

Participants are required to be WeChat and smartphone users.

Written informed consent will be obtained.

Patients will be excluded for the following reasons: pregnancy; malignant tumour or end-stage disease with a life expectancy of <1 year; prescription for a shorter course of DAPT at discharge; refusal to use social media; refusal to provide written informed consent for this study.

All patients will receive training on using the app when they enrolled. They will receive a brochure on using the applet and staff guidance. All patients assigned to the intervention group will receive personalised social media interventions four times a week.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation will be performed using a centralised, computerised randomisation programme in a uniform 1:1 allocation ratio. The intervention programme will be initiated after patients have been enrolled. The patients (but not their care providers), and research personnel will be unaware of their allocation. The study coordinators and research assistants conducting the assessments and the statisticians will also be blinded. This randomisation programme is electronically linked to the applet delivering the interactive responses and messages, thereby minimising the need for human interference. Key participant characteristics that will determine intervention customisation and personalisation will also be automatically imported into the applet administering the intervention.

The control group

The control group will receive standard care as determined by their usual doctors. Typical secondary prevention cardiovascular medications include antithrombotic drugs, β-blockers, statins and ACE inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blockers. Control group patients will receive messages four times a week, including cardiovascular knowledge and follow-up reminders, such as risk factors for CHD and typical symptoms of myocardial infarction.13 These patients will have follow-up visits after 6 and 12 months, and they will undergo a physical examination, lifestyle assessment, drug adherence status evaluation and therapy adjustment. In order to balance the potential influence by social media, controls will also receive the educational material.14

The intervention group

The intervention group will receive the usual messages (online supplementary eTable 1) with additional personalised reminders that will include a series of messages focusing on medication adherence. They will also receive autoresponses and backstage counselling over the 12-month study period as detailed below.

bmjopen-2019-033017supp001.pdf (110.2KB, pdf)

The interventions for this group are listed but not limited to the following points:

Medication reminders

Patients’ personal information will be assessed when they are enrolled. The mHealth tool will provide special interventions according to the patients’ medical history. For example, patients who smoke will be advised to quit smoking. Every patient will receive a health report monthly, which will reflect their drug compliance, blood pressure, heart rate, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and smoking status.

Patients’ medication information will be recorded by obtaining pictures of their medication. Patients will be asked to use the punch time clock in the mHealth tool. If they forget to punch in, they can do so whenever they think of it. If there is no record of medication for 3 days, the intervention group patients will receive SMS alerts and phone over 7 days.

Interactive responses

Autoresponse: after sending personal or discomfort symptom questions, patients will be provided with an automatic response pushed by the back-end database that crawls the keywords. The tool suggests that the answer is just for reference. If the intervention group patients have urgent questions, they will be advised to consult their clinicians.

The researchers will communicate with the patients once a month. If there is an emergency message, the applet will remind the patient to go to the hospital for immediate treatment/first aid.

Follow-up

Blood pressure, heart rate, heart rhythm, body weight, lifestyle assessment findings, medication and medication adjustment will be recorded at 6 and 12 months after enrollment. The patients’ medication adherence will be evaluated by PDC according to their prescriptions. MACEs will include all-cause mortality, rehospitalisation, target vessel revascularisation and stroke. The research staff will carefully collect all information through outpatient/telephone call follow-ups.

Timeline

1 June 2018–30 September 2018: ethical application for research proposal is approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital Ethics Research Committee

1 October 2018–31 December 2018: mobile health tools are developed in collaboration with relevant technology companies. A pilot phase takes place in 36 patients for design optimisation.

1 January 2019–31 December 2020: enrollment is to be completed over 24 months, and at least 760 patients are to be randomly allocated to the control group or the intervention group.

1 December 2021–1 January 2022: follow-up and interim analysis are performed.

Study endpoints

Primary outcome

The primary endpoint will be the discontinuation rate of any antiplatelet drug within 1 year of DES implantation. The discontinuation duration will be further segmented into periods after the index disruption event, that is, brief (1–7 days), temporary (8–30 days) and permanent (>30 days), according to follow-ups and records of medication adherence in the applet.6

Key secondary outcomes

The secondary endpoints will be as follows:

Medication adherence: we will assess the patients’ DAPT adherence according to PDC by prescription.

MACEs, including all-cause mortality, target vessel revascularisation, non-fatal myocardial infarction and stroke.

Definition

DAPT is defined as the combination of aspirin and an oral inhibitor of the P2Y12 receptor for adenosine 5’-diphosphate.15

Oral inhibitors of the P2Y12 receptor include ticagrelor and clopidogrel.16 Other drugs, such as prasugrel, will not be included because they are not yet available in the Chinese market.

Medication change will be defined as any modification between ticagrelor and clopidogrel under doctors’ advice (table 1).

Table 1.

Outcome definitions

| Term | Definition |

| Dual antiplatelet drug discontinuation | Discontinuation of any dual antiplatelet drug owing to patients’ discretion, including bleeding or non-compliance, rather than doctors’ advice. Changing of DAPT medication between ticagrelor and clopidogrel under doctors’ advice will not be identified as dual antiplatelet drug discontinuation; such changing at patients’ discretion will be identified as such6 |

| Dual antiplatelet drug discontinuation duration | Is further divided into brief (1–7 days), temporary (8–30 days) and permanent (>30 days)6 |

| Medication adherence | Is further divided into poor (PDC <40%), moderate (40%–80%) and good (PDC >80%) based on the number of days the patients take their medicine6 |

| All-cause mortality | Any death recorded between the date of enrollment and the end of data linkage |

| Target vascular revascularisation | Any revascularisation procedure involving percutaneous coronary intervention of the target lesion or surgical bypass of the target vessel |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) | Typical rise and fall of biochemical markers of myocardial necrosis to greater than twice the ULN; or, if markers are already elevated, further elevation of a marker to >50% of a previous value that had been decreasing, and >2 × ULN, with ≥1 of the following: 1) ischaemic symptoms, 2) development of new pathologic Q waves, 3) ECG changes of new ischaemia or 4) pathological evidence of MI3 |

| Stroke | The presence of a new focal neurological deficit thought to be vascular in origin, with signs or symptoms lasting >24 hours. It is strongly recommended (but not required) that an imaging procedure, such as CT or MRI, be performed. |

DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; PDC, proportion of days covered; ULN, upper limits of normal.

Reporting and evaluating clinical adverse events

The researchers at each centre will carefully observe the main clinical adverse events that occur during the clinical study. They will query and inspect them carefully according to the ‘Clinical Incident Registration Form’. They will fill out the ‘Clinical Event Registration Form’ in the Case Report Form and save all relevant clinical data. Clinical data related to clinical adverse events will be reported to the Department of Cardiology, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Guangdong Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases and the subcentre’s clinical event committee for assessment. At least two specialist clinicians will be required for confirmation. Any symptoms of discomfort will be self-reported via social media.

Data and safety monitoring board

A committee of clinicians and a biostatistician will periodically review and evaluate the accumulated study data for participants’ safety, progress (if appropriate) and efficacy. They will make recommendations to the principal investigators concerning the continuation, modification of enrollment or termination of the trial. The hospital’s academic committee has approved the study design. Confidentiality agreements have been signed with third-party companies.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will follow the principles of the Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration. Before the trial begins, the Principle Investigator (PI) at each subcentre will be responsible for submitting the necessary information, such as the research plan and informed consent documents to the ethics committee for review. It will be the responsibility of the investigator to explain the study’s purpose, methodology, benefits and potential adverse events of the interventions. All enrolled patients will be required to provide written, informed consent to participate in this study. The investigator must obtain informed consent from the legal parent or legal guardian of patients who are unable to make a legally binding decision for any reason. Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital’s institutional ethics review board has approved the study’s design.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation will be based on a previous study.6 With a test level of 0.05, test efficiency of 80%, 1-year incidence rate in the control group of 24%, 1-year incidence rate in the test group of 15%, significance level of 0.05, power of 80% and dropout rate of <20% and a two-sided χ2 test, 380 subjects will be required in each group. A total of 760 patients will be needed in the two groups.

Comparisons between normally distributed continuous variables, expressed as means±SD, will be performed using two-sample t-tests. Non-normally distributed continuous variables, presented as medians and IQRs, will be analysed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Pearson χ2 or Fisher’ exact tests will be used, as appropriate, for categorical data, which will be expressed as percentages. The primary and secondary endpoints will be analysed in accordance with the intention-to-treat principle. All tests will be two tailed, and a p-value of <0.05 will be considered statistically significant. To account for group effects and correct baseline characteristics, the primary endpoint will be compared using a generalised assessment equation, and the SAS V.9.3 will be employed for all analyses. Subgroups will also be analysed, such as age, education level and socioeconomic status, using logistic regression models with the intervention group.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of the study, including the development of the research question, outcomes measures, recruitment to or conduct of the study. The results of the study will be disseminated to the public as deemed appropriate by public health officials.

Discussion

We hypothesise that social media interventions will yield better DAPT adherence in patients with CHD who undergo DES implantation within 1 year.

Despite conclusive evidence on the effectiveness of DAPT, DAPT discontinuation frequently occurs for various reasons, which can lead to many adverse outcomes. Cutlip et al found that incidence of antiplatelet drug cessation was about 9.6% in 2159 patients with DES within 6 months after operation. And the risk of death or recurrent myocardial infarction in those patients with poor compliance was higher (7.6% vs 3.0%, p<0.001).17 In Asian, the early discontinuation rate was 31.0%. It seems to be significantly higher than those reported from prospective studies, which may more likely reflect the real-world situation.18

Previous studies have shown that using mobile medical interventions, even with simple methods, can improve patients’ lifestyle and risk factors (online supplementary eTable 2). The SimCard Trial19 has shown that patient management with the use of social media can improve the blood pressure control rate in Asians. It provided evidence that smartphones can promote multifactorial interventions for secondary prevention of CHD. The Tobacco, Exercise and DietMessages (TEXT ME) trial study,12 a randomised controlled trial with 6 months of follow-up, enrolled 710 patients with CHD. The intervention group received four messages per week, which included four aspects: smoking intervention, diet, physical activity and general coronary health education. Conversely, the control group received standard care only. The intervention group’s low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure and body mass index significantly improved. The TEXT ME study occurred in a single centre and had only 6 months of follow-up; nevertheless, it provided a good model for other mobile-based intervention research and design involving social media.

Although the concept of social media-based interventions is not new, it may be a good method for promoting medication adherence, considering the rapidly increasing application ratio of smartphones.20–23 After analysing our previous questionnaire and investigating the current chronic disease management software on the market, the project’s clinical and academic teams and the collaborating technology company jointly developed a CHD management programme, which has been internally verified and externally qualified. Rather than creating a brand new application, our applet is based on WeChat, which has approximately 700 million active users. Our applet will intervene in the patients and their families in various aspects: lifestyle, health education, self-management, supervision, behavioural and medical consultation and treatment adherence evaluation, all of which are associated with improvement in communication efficiency and patient compliance.

In conclusion, we designed this single-blind, multicentre, randomised study to explore whether a social media-based intervention would be effective in enhancing DAPT compliance across multiple hospitals among patients with CHD who have undergone DES implantation within 1 year.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @liujin

G-lS, LL, LL and JL contributed equally.

Contributors: YL and J-yC had the original idea. G-lS, LL S-qC, JL, YH, ZG and LL contributed to the study design. S-qC and JL were involved in the design of the statistical analysis approach. YH, ZG, XD and LH were involved in literature review and developing study instruments and materials. JY, YL, GC and YH are site PI participated in conducting the trial and acquisition of data. YL, G-lS, LL and LL drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed critical intellectual input and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the major funding bodies, the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital Clinical Research Fund (2014dzx02), Cardiovascular Research Foundation Project of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association (SCRFCMDA201216) and CS Optimizing Antithrombotic Research Fund (BJUHFCSOARF201801-10).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital Ethics Research Committee (GDREC2018327H). Results will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and presentations at international conferences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Lin JS, Evans CV, Johnson E, et al. Nontraditional risk factors in cardiovascular disease risk assessment: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services Task force. JAMA 2018;320:281–97. 10.1001/jama.2018.4242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2016 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2016;133:e38–60. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J 2019;40:87–165. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrières J, Lautsch D, Ambegaonkar BM, et al. Use of guideline-recommended management in established coronary heart disease in the observational DYSIS II study. Int J Cardiol 2018;270:21–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kedhi E, Fabris E, van der Ent M, et al. Six months versus 12 months dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (DAPT-STEMI): randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2018;363 10.1136/bmj.k3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehran R, Baber U, Steg PG, et al. Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention (Paris): 2 year results from a prospective observational study. The Lancet 2013;382:1714–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61720-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cutlip DE, Kereiakes DJ, Mauri L, et al. Thrombotic Complications Associated With Early and Late Nonadherence to Dual Antiplatelet Therapy. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2015;8:404–10. 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Irvin MR, Shimbo D, Mann DM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of low medication adherence in apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2012;14:694–700. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00690.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:177–86. 10.1001/jama.297.2.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patel R, Chang T, Greysen SR, et al. Social media use in chronic disease: a systematic review and novel taxonomy. Am J Med 2015;128:1335–50. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Redfern J, Ingles J, Neubeck L, et al. Tweeting our way to cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1657–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chow CK, Redfern J, Hillis GS, et al. Effect of Lifestyle-Focused text messaging on risk factor modification in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA 2015;314:1255–63. 10.1001/jama.2015.10945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Widmer RJ, Allison TG, Lerman LO, et al. Digital health intervention as an adjunct to cardiac rehabilitation reduces cardiovascular risk factors and rehospitalizations. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2015;8:283–92. 10.1007/s12265-015-9629-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nolan RP, Liu S, Feldman R, et al. Reducing risk with e-based support for adherence to lifestyle change in hypertension (reach): protocol for a multicentred randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003547 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Costa F, Van Klaveren D, Feres F, et al. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Duration Based on Ischemic and Bleeding Risks After Coronary Stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:741–54. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of cardiology (ESC) and of the European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2018;39:213–60. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cutlip DE, Kereiakes DJ, Mauri L, et al. Thrombotic complications associated with early and late nonadherence to dual antiplatelet therapy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:404–10. 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho MH, Shin DW, Yun JM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of early discontinuation of Dual-Antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation in Korean population. Am J Cardiol 2016;118:1448–54. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tian M, Ajay VS, Dunzhu D, et al. A cluster-randomized, controlled trial of a simplified multifaceted management program for individuals at high cardiovascular risk (SimCard trial) in rural Tibet, China, and Haryana, India. Circulation 2015;132:815–24. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Brindle P, et al. Discontinuation and restarting in patients on statin treatment: prospective open cohort study using a primary care database. BMJ 2016;353 10.1136/bmj.i3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santo K, Hyun K, de Keizer L, et al. The effects of a lifestyle-focused text-messaging intervention on adherence to dietary guideline recommendations in patients with coronary heart disease: an analysis of the text me study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15 10.1186/s12966-018-0677-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dorje T, Zhao G, Scheer A, et al. Smartphone and social media-based cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention (SMART-CR/SP) for patients with coronary heart disease in China: a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021908 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neubeck L, Lowres N, Benjamin EJ, et al. The mobile revolution—using smartphone apps to prevent cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:350–60. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033017supp001.pdf (110.2KB, pdf)