Abstract

Objectives

To define the core competencies essential for specialist training in neurocritical care in China.

Design

Modified Delphi method and nominal group (NG) technique.

Setting

National.

Participants

A total of 1094 respondents from 33 provinces in China participated in the online survey. A NG of 11 members was organised by the Neuro-Critical Care Committee affiliated with the Chinese Association of Critical Care Physicians and the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases.

Results

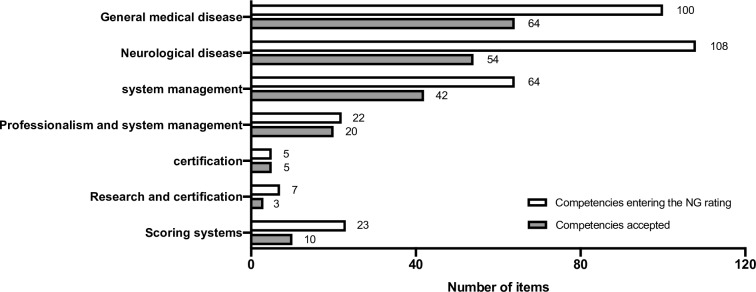

1094 respondents from 33 provinces in China participated in the online survey. A formal list containing 329 statements was generated for the rating by a NG. After five rounds of NG meetings and one round of comments and iterative review, 198 core competencies (54 on neurological diseases, 64 on general medical diseases, 42 on monitoring of practical procedures, 20 on professionalism and system management, five on ethical and legal aspects, three on the principles of research and certification and 10 on scoring systems) formed the final list.

Conclusion

By using consensus techniques, we have developed a list of core competencies for neurocritical care training, which may serve as a reference for future specialist training programmes in China.

Keywords: neurocritical care, training, core competency, consensus, Delphi, nominal group

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that core competencies for neurocritical care has been established in China.

Consensus techniques were employed in our study, which may serve as a reference for future specialist training programmes in China.

All of the nominal group members came from tertiary academic hospitals so they might not have represented the views of lower-grade hospitals.

Introduction

During the past three decades, neuro-intensive care units (NICUs) in China grew rapidly with the development of neuroscience and critical care medicine.1 2 A recent survey demonstrated that most of the NICUs in China are operated under a ‘closed’ model and that clinical practice is conducted by full-time dedicated neuro-intensivists.3 Systemic professional training and the performance assessment of physicians involved in neurocritical care practice are among the cornerstones of the development of the NICU.4 At present, professional training programmes focusing on critical care medicine and neurosurgery have been put into practice in China.5 However, there is no standardised national training programme for neuro-intensivists.

The experience of critical care and neurocritical care training in other countries has already illustrated that identifying core competencies is important for establishing standardised training programmes.6–8 To date, no core competency lists are available for neurocritical care training in China. Recently, a list of competencies for general critical care training has been established.9 However, since neurocritical care is a multidisciplinary subspecialty that contains the characteristics of neurology, neurosurgery and critical care medicine, it is inappropriate to directly apply critical care or neurological/neurosurgical lists for neurocritical care. The United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties (UCNS) and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) have published their core competency lists for neurocritical care training, respectively.7 10 Both were generated based on the opinions of experts. Additionally, due to the diversity of medical resources and educational systems in China, the establishment of NICUs is extremely imbalanced across different regions.3 Therefore, consensus statements issued by other countries may not be applicable for NICUs in China.

The Neuro-Critical Care Committee affiliated with the Chinese Association of Critical Care Physicians (NCCC-CACCP) and the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases called for a working group to generate a list of fundamental core competencies for neurocritical care training in China. The modified Delphi method and nominal group (NG) technique were used during consensus establishment. The methodology and results of the present study might provide a reference for future specialist training programmes in different regions.

Methods

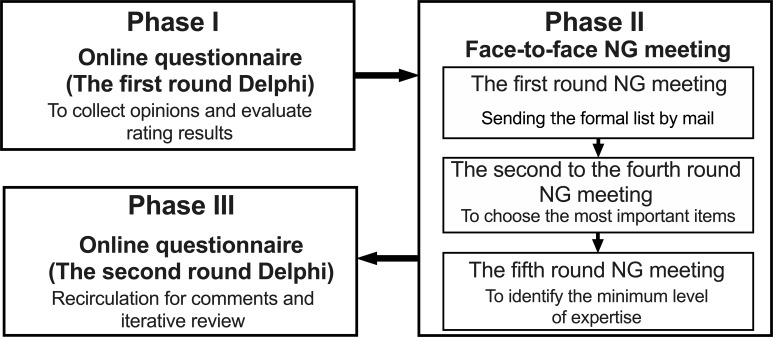

The present study was conducted in three phases from February 2018 to May 2019 (figure 1). In phase I (the first round Delphi), a nationwide questionnaire was published online to collect opinions on the core competencies that provided a basic perspective for the specialists training in neurocritical care. In phase II, several rounds of voting were conducted by face-to-face NG meetings to generate a core competencies list. Then the minimum level of expertise, which is equated with the ability that should be attained at the end of training, was identified by one round of voting. During phase III (the second round Delphi), the draft was posted online for further comments.

Figure 1.

The study was conducted in three phases. In phase I, a competencies list was generated and arranged during the first round of Delphi. In phase II, five rounds of nominal group (NG) meetings were conducted to confirm the competencies list and levels of expertise. In phase III, comments and iterative review were recirculated during the second round of Delphi.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this study.

Phase I: generation and rearrangement competencies list (first round Delphi)

A list of potential core competencies was developed based on four previous publications, including the list introduced by the Competency-Based Training in Intensive Care Medicine in Europe Collaboration (CoBaTrICE),6 the guidelines developed by UCNS,7 the Chinese College of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (CCICCM)9 and the Critical Care and Emergency Medicine fellowship core curriculum of AAN.10 In principle, all core competencies proposed by the aforementioned publications were preserved, while the duplicated items were rearranged to simplify the list. Those items with a definition of the level of expertise were modified. For example, the items about shock in CCICCM (to recognise and manage different types of shock) and UCNS (shock: hypotension) and its complications (vasodilatory and cardiogenic) were rewritten as ‘different types of shock’ in the potential list. Furthermore, since there were very few items in the published guidelines relevant to scoring system for patient assessment, we added five new items related to the scoring system.

The potential competencies list was translated into Chinese and organised into an online questionnaire (https://www.wjx.cn/jq/21776519.aspx, accessed 2 April 2018), which comprised seven parts (general medical diseases, neurological diseases, monitoring practice, professionalism and system management, ethical and legal, research and certification, and scoring system). The respondents were asked to select ‘YES’ or ‘NO’ for each item. Respondents were also invited to answer an open question: ‘Which competencies are important for specialist training in neurocritical care, in addition to those listed above’.

The online questionnaire was disseminated via three types of media:

Members of the NCCC-CACCP from each province were responsible for the distribution of the questionnaire via email, WeChat or website links.

The questionnaire was posted on the official website of the Chinese Society of Critical Care Medicine (http://www.csccm.org.cn, accessed 2 April 2018).

The questionnaire was posted on the WeChat official account of the Department of Critical Care Medicine of Capital Medical University (https://www.wjx.cn/jq/21776519.aspx, accessed 2 April 2018).

We used WeChat as the primary disseminating means because it is the most popular social media not only in China but in the entire Chinese community. WeChat integrates the functions of WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook.

The questionnaire was posted online for 90 days. After removing duplicate and meaningless responses from the ‘open question’, the remaining responses and all those items that received at least one ‘YES’ response were generated into a formal list for the NG meeting.

Phase II: NG ratings

The leaders of the NCCC-CACCP and the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases were responsible for the establishment of NG. Considering the imbalance of medical resources in China, 11 NG members from different regions were invited, covering areas from economic development to underdevelopment (six provinces: Beijing, Shanghai, Shandong, Shanxi, Guangdong, Xinjiang). There were four neuro-intensivists with neurological/neurosurgical background, three general intensivists in charge of NICUs, two trainees who had completed training in neurocritical care, one respiratory therapist and one experienced neurocritical care nurse. A researcher was selected as the coordinator to facilitate the process. The four neuro-intensivists and three general intensivists were all engaged in graduate, postgraduate medical education and in charge of physician training programme. The three general intensivists in the NG were specialist training (similar with fellowship training in USA) directors of critical care medicine and the four neuro-intensivists were residency training directors on neurology or neurosurgery.

To improve efficiency, the first round of NG rating was conducted by sending the formal list generated after the online survey to the NG members by mail. All of the competencies were followed by the same question: ‘Is it important for specialists training in neurocritical care?’. Meanwhile, the percentages of ‘YES’ responses selected during the online questionnaire were provided. The NG members were asked to individually rate the importance of competencies using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 representing very unimportant to 5 representing very important),6 and to return the feedback in 1 week.

The coordinator was in charge of analysing the feedback of the questionnaires. Items achieving full consensus (100% NG members voting 4-point or 5-point) were directly entered into the final list. Other undetermined items were emailed to the NG members 1 week before the plenary NG ratings. Data on personal and group ratings for each item during the first round were provided as well. The NG members were requested to read these materials carefully and compare the differences between their own opinions and those of other NG members.

A face-to-face NG meeting was held on 21 July 2018 (the second round NG rating). Each NG member was required to select at least the five most important items individually from those items entered in the second round of ratings. Each NG member was asked to explain the reasons for selecting these items in turn, and others were not allowed to interrupt during this process. Afterwards, an open discussion for debate was conducted. During the meeting, the NG members were frequently reminded to consider the resource disequilibrium of the national medical system and respect the opinions of the ‘vulnerable members’ such as trainees, nurses and respiratory therapists. Finally, each member rated the importance of competencies independently, as in the first round. Items achieving full consensus entered into the final list; otherwise, they were entered into the third round. The third and fourth rounds were conducted in the same manner as the second round. Since no item achieved full consensus (100% NG members voting 4-point or 5-point) during the fourth round, the iteration ended. All the items that did not achieve full consensus were eliminated. The resulting data from the previous rounds were presented to the NG members during the meeting.

The fifth round NG rating was held on 22 July 2018. The NG members were required to identify the minimum level of expertise for each competence item, which was defined at four levels: a, b, c and d. We used the CoBaTrICE approach6 to describe the level of expertise in the competence statements: a=has knowledge of or describes … ; b=performs, manages, conducts, demonstrates, assesses or interprets … under supervision; c=performs, manages, conducts, demonstrates, assesses, interprets … independently; d=teaches or supervises others to perform (selected from the generic descriptors, online supplementary appendix 1, table S1). A simple majority rule was implemented; that is, the level that gained the most votes was accepted as the final choice. When the number of votes was the same, the lower level would be accepted. For example, if five ‘b’, five ‘c’ and one “d” were voted, the level ‘b’ would be accepted as the minimum level of expertise.

bmjopen-2019-033441supp001.pdf (190.6KB, pdf)

All NG members participated in all of the five rounds NG meetings.

Phase III: comments and iterative review (second round Delphi)

The draft of the final list was delivered by three types of media, as with the first round of Delphi. All participants who provided an email address during the online survey were contacted and invited to give comments.

Development of the final set

After the three phases of the study, the final competence set was constructed as the statements were made of three parts: ‘context’, ‘level of expertise’ and ‘content of competence’ (online supplementary appendix 1, table S2).

The number of items in the final competence set was compared with those in guidelines and statements published by CoBaTrICE, UCNS, CCICCM and AAN.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as number (percentage). Continuous data were presented as the median and the IQR. All data were analysed using SPSS V.17.0.

Results

Phase I: generation and rearrangement competencies list (first round Delphi)

A total 1094 respondents from 33 administrative provinces (including Macao and Taiwan) participated in the first round of Delphi (table 1). There were 916 (83.7%) respondents from tertiary hospitals, 536 (49.0%) of whom had been engaged in clinical practice for more than 10 years. Each item in the original online questionnaire won at least one vote, so all entered the NG rating. The open question received 394 additional suggestions, most of which had already been included in the original online questionnaire. Finally, 37 suggestions (22 relating to knowledge and skills and 15 relating to the scoring system) were included in the formal list after careful consideration. Following the rule that we not delete items but only analyse and integrate them, a formal list containing 329 statements was ultimately generated for the following NG ratings (online supplementary appendix 1, tables S3 and S4).

Table 1.

The professional background of participants in Delphi

| Specialist | First round Delphi | Second round Delphi |

| General intensivists | 412 (37.7%) | 49 (44.1%) |

| Neurosurgeons | 244 (22.3%) | 18 (16.2%) |

| Neurologists | 139 (12.7%) | 9 (8.2%) |

| Neuro-intensivists | 95 (8.7%) | 22 (19.8%) |

| Medical physicians (except neurologists) | 53 (4.8%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Surgeons (except neurosurgeons) | 25 (2.3%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Emergency physicians | 20 (1.8%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Anaesthesiologists | 13 (1.2%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Rehabilitation physicians | 4 (0.4%) | 0 |

| Nurses | 70 (6.4%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Respiratory therapists | 7 (0.6%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Medical students | 12 (1.1%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Total | 1094 | 111 |

Phase II: NG ratings

During the first round of ratings, 138 (41.8%) items achieved full consensus. Then, 52 (15.8%) and eight (2.4%) items were elected during the second and third rounds, respectively. In the fourth round, no additional items achieved full consensus; therefore, the rating was terminated. Finally, a list containing 198 items was generated (online supplementary appendix 1, Table S3). Another 131 items that did not reach full consensus were eliminated (online supplementary appendix 1, table S4).

The minimum level of expertise was identified in the fifth round of rating. Following the established rules, most items were rated as level ‘c’ (159, 80.3%), with one ‘a’ (0.5%), 28 ‘b’ (14.1%) and 10 ‘d’ (5.0%) ratings. Nineteen items had the same rating results in two levels of expertise, and the lower level was accepted as the final level. For example, the item ‘9.5 Describes burns and electrical injury’ was voted as five ‘a’, five ‘b’ and one ‘c’. According to the rule, the level ‘a’ was accepted.

Phase III: comments and iterative review (second round of Delphi)

There were 111 replies received from 27 provinces (table 1). No new competencies were proposed during this phase, so no change was made to the final competency list. It is worth noted that many participants expressed their urgent demand for standardised neurointensive training.

Development of the final set

The final competence set comprised 198 competency statements divided into seven parts (figure 2, online supplementary appendix 2). Online supplementary appendix 2 also shows the overlap of our core competences with those from other international organisations.

Figure 2.

The numbers of competencies categorised into seven different themes. The number of competencies entering the nominal group (NG) rating that were finally accepted are shown.

bmjopen-2019-033441supp002.pdf (209KB, pdf)

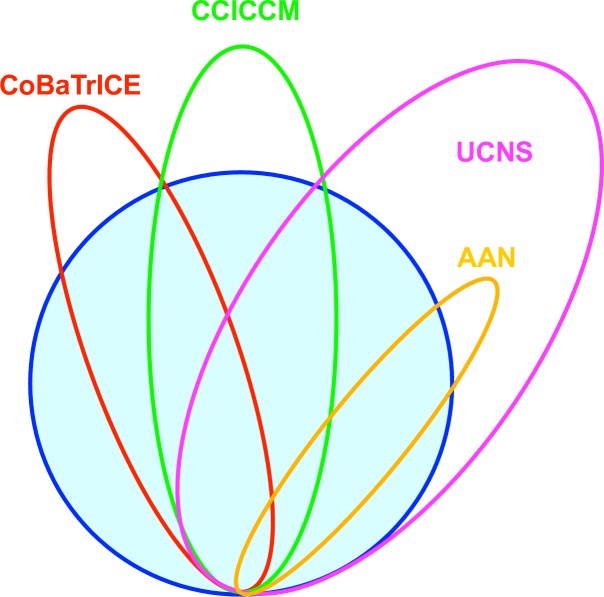

The number of items in the final competence set (n=198) was more than the number in CoBaTrICE (n=102), CCICCM (n=129) and AAN (n=66) but was less than the number in UCNS (n=289) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The intersection among the competencies list developed in the present study (n=198, blue circle) with other guidelines and statements, including the competency based training in intensive care medicine in Europe collaboration (CoBaTrICE) (n=102, red circle), the Chinese College of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (CCICCM) (n=129, green circle), the United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties (UCNS) (n=289, magenta circle) and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) (n=66, orange circle).

Discussion

Based on past guidelines, we used consensus techniques, that is, the modified Delphi method and NG technique, to develop a set of 198 core competencies for fundamental neurocritical care training in China. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that consensus techniques have been applied to the development of core competencies of neurocritical care in China. On behalf of the Working Group of the National Center of Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological System Diseases, we will implement this document of core competencies through this administration organisation, and the implementation of this consensus will be one of the indicators for quality management of neurocritical care.

The Delphi method and NG technique are the most commonly employed techniques for developing consensus.11 These methods have been used successfully in critical care medicine, for instance, to identify the core competencies of critical care in Europe6 and China9 and to establish national research priorities of critical care in the UK.12 The Delphi method is used to collect opinions and evaluate rating results. This technique was initially described by the RAND Air Force Corporation in America in the 1950s.13 In the field of medical education, more than three quarters of publications using consensus techniques adopted the Delphi and modified Delphi.14 This methodology permits individual thinking. In phase I Delphi, our survey was open to respondents with different backgrounds to collect ideas and suggestions as much as possible on topics such as ethics and professionalism. The NG technique is employed to select the most important items and define the minimum level of expertise. During face-to-face ratings, the interaction is controlled by a coordinator so that all participants have opportunities to express their views and the dominance of one or two vocal members can be avoided.11 Later, the free period allows for more expression of ideas and discussions. The design of our study shares many similarities with CoBaTrICE,6 except for one step order. In our study, we adhered the principle that determining the core competencies is the top priority. The most important items were voted on prior to the determination of the minimum level of expertise. The purpose of this adjustment was to avoid the potential influence of the minimum level of expertise on the voting process on the importance of the competencies. For example, if the item was previously categorised as level ‘a’, it may have been interpreted as ‘unimportant’ and ruled out during the voting on importance.

The number of our items was significantly reduced compared with UCNS7 (figure 3). The main reason is that we wanted to obtain a basic list with the greatest consensus. Therefore, only those competencies agreed on by all NG members were included. For example, one NG member insisted that research capacity was not essential for junior physicians. Under the established admission criteria, most items relevant to research capacity were ruled out. In addition, the differences in the professional backgrounds of the NG members lead to divergences. For example, some NG members with a neuroscience background believed that the ultrasound technique was not so important, while NG members specialised in general critical care insisted that ultrasound was an essential skill for clinical practice. This phenomenon may be associated with the popularity of ultrasound in the two specialties.15 16 After repeated discussions, three items were admitted in the third round (pleural effusion and ascites localisation, assesses inferior caval vein and vascular localisation), although more advanced techniques such as lung ultrasound and echocardiography were excluded. Compared with CCICCM,9 our list not only added a large number of neurological items but also added some items related to systemic diseases related to neuroscience to adapt to neurocritical care training. More than 30 items related to general critical care were deleted, such as ‘Manages continuous renal replacement therapy’. Furthermore, the 15 newly added items were all from the first round of Delphi, which highlighted the importance of the Delphi method and avoided the loss of important items. The comparison of our core competences with those from CoBaTrICE, CCICCM, AAN and UCNS (online supplementary appendix 2) might help these international organisations to modify and enhance their core competencies.

Neurocritical care is an interdisciplinary specialty involving neuroscience and critical care medicine.17 18 In China, NICUs fall under different departments and are managed by neurosurgeons, neurologists or intensivists.3 The training requirements of different regions and backgrounds are highly diverse. An all-embracing competency list could be a burden for a training programme and may decrease efficiency. Our lists selected essential fundamental competencies for physicians who had just finished neurocritical care training, regardless of whether a training programme was based on neurosurgery, neurology, critical care medicine or other specialties related to neurocritical care. Training programme directors may reorganise this list by adding core competencies for any special local training. Those items that had been ruled out during the NG process might serve as optional competencies. For those trainees after neurological and neurosurgical training, general critical care training items may be added according to our core competencies list and those from CCICCM.9 Although all of the items have reached consensus after the NG rating, the content and minimum level of expertise on some items may be controversial. In addition, some clinically relevant conditions, such as brain death, were not included in the final lists. However, we must report according to the results of the vote. Readers and training programme directors should be aware of potential disputes and make adjustment as needed.

There are some potential limitations in our study. First, we used WeChat as one of the media to disseminate online questionnaires to maximise the efficiency and enthusiasm of the participants. Therefore, it is inevitable that some feedback was of low quality and given without consideration. Fortunately, among more than 1000 respondents, the proportion of low-quality responses was quite low, so there was not much impact on the final results. Additionally, in both rounds of Delphi, we used the WeChat to deliver our questionnaires. Although the WeChat is powerful and highly efficient, we have to admit that by this way, we are unable to obtain the exact number of participants who the questionnaires were sent to. Therefore, we cannot tell the ‘denominator’ for the number of stakeholders invited to participate in either round of the Delphi. Thus, the response rate cannot be identified. Second, although we had reminded the experts to pay attention to the opinions of vulnerable groups and the voting processes were independent, trainees, nurses and respiratory therapists were still less involved in the discussion. By analysing the questionnaires, we could not rule out the suspicion of conformity in the selection of some items. Third, all of the NG members came from tertiary academic hospitals so they may not have represented the views of lower-grade hospitals. However, one-seventh of the replies were received from lower-grade hospitals in phase I, which provided a reference for the NG meetings. In addition, the NG members were reminded to consider the resource disequilibrium during the voting processes. Finally, patients and their relatives were not invited to participate in our study, which therefore might have lacked their opinions. However, the CoBaTrICE invited patients and their relatives to give their opinions, and all these items were incorporated into our potential list.

Conclusions

In summary, by using consensus techniques, we have developed a list of core competencies for Chinese neurocritical care training that may serve as a reference for future specialist training programmes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

LinlinZ and J-XZ contributed equally.

Collaborators: The authors is on behalf of the Working Group from Neuro-Critical Care Committee affiliated to the Chinese Association of Critical Care Physicians and the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases.

Contributors: LinlinZ and J-XZ conceived the study. Statistical design and analysis were done by ZC and YumW. ZC, LinlinZ and J-XZ drafted the initial version of the manuscript. ZC, LG, QBH, LHL, BHQ, GZS, XYY, YaW, LiZ, YumW, LinlinZ and J-XZ participated nominal group meeting. All authors revised and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the IRB of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. KY2017-034-02). Since no patients were involved in the study, our local IRB approved a waiver of informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Huang M, Wang J, Ni X, et al. Neurocritical care in China: past, present, and future. World Neurosurg 2016;95:502–6. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang J, Bai L, Shi M, et al. Trends in age of first-ever stroke following increased incidence and life expectancy in a low-income Chinese population. Stroke 2016;47:929–35. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Su Y-Y, Wang M, Feng H-H, et al. An overview of neurocritical care in China: a nationwide survey. Chin Med J 2013;126:3422–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dhar R, Rajajee V, Finley Caulfield A, et al. The state of neurocritical care fellowship training and attitudes toward accreditation and certification: a survey of neurocritical care fellowship program directors. Front Neurol 2017;8:548 10.3389/fneur.2017.00548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China Recommendation for conducting specialist training program in China, 2016. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/qjjys/s3593/201601/0ae28a6282a34c4e93cd7bc576a51553.shtml [Accessed 29 May 2019].

- 6. Bion JF, Barrett H, CoBaTrICE Collaboration . Development of core competencies for an international training programme in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1371–83. 10.1007/s00134-006-0215-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mayer SA, Coplin WM, Chang C, et al. Core curriculum and competencies for advanced training in neurological intensive care: United Council for neurologic subspecialties guidelines. Neurocrit Care 2006;5:159–65. 10.1385/NCC:5:2:159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen AS, Izzy S, Kumar MA, et al. Education research: variation in priorities for neurocritical care education expressed across role groups. Neurology 2018;90:1117–22. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu X, Xi X, Ma P, et al. Consensus development of core competencies in intensive and critical care medicine training in China. Crit Care 2016;20 10.1186/s13054-016-1514-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Academy of Neurology Critical care & emergency medicine fellowship core curriculum, 2019. Available: https://www.aan.com/tools-and-resources/academic-neurologists-researchers/program-and-fellowship-director-resources/aan-core-curricula/ [Accessed 29 May 2019].

- 11. Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical Guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:i–iv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldfrad C, Vella K, Bion JF, et al. Research priorities in critical care medicine in the UK. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:1480–8. 10.1007/s001340000628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Helmer O, Dalkey N. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Wood TJ, et al. The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research. Academic Medicine 2017;92:1491–8. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wong A, Galarza L, Duska F. Critical care ultrasound: a systematic review of international training competencies and program. Crit Care Med 2019;47:e256–62. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rajajee V, Díaz-Gómez JL. Critical care ultrasound should be a priority first-line assessment tool in neurocritical care. Crit Care Med 2019;47:833–6. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Markandaya M, Thomas KP, Jahromi B, et al. The role of neurocritical care: a brief report on the survey results of neurosciences and critical care specialists. Neurocrit Care 2012;16:72–81. 10.1007/s12028-011-9628-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin A, Chen ML, Chatterjee A, et al. Specialty classifications of physicians who provide neurocritical care in the United States. Neurocrit Care 2019;30:177–84. 10.1007/s12028-018-0598-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033441supp001.pdf (190.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033441supp002.pdf (209KB, pdf)