Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the association between cardiovascular risk factors and Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS) score in the Romanian population. CAD-RADS is a new, standardised method to assess coronary artery disease (CAD) using coronary CT angiography (CCTA).

Design

A cross-sectional observational, patient-based study.

Setting

Referred imaging centre for CAD in Transylvania, Romania.

Participants

We retrospectively reviewed 674 patients who underwent CCTA between January 2017 and August 2018. The exclusion criteria included: previously known CAD, defined as prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (n=91), cardiac CT for other than evaluation of possible CAD (n=85), significant arrhythmias compromising imaging quality (n=23). Finally, 475 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Methods

Demographical, clinical and CCTA characteristics of the patients were obtained. CAD was evaluated using CAD-RADS score. Obstructive CAD was defined as ≥50% stenosis of ≥1 coronary segment on CCTA.

Results

We evaluated the association between risk factors and CAD-RADS score in univariate and multivariable analysis. We divided the patients into two groups according to the CAD-RADS system: group 1: CAD-RADS score between 0 and 2 (stenosis <50%) and group 2: CAD-RADS score ≥3 (stenosis ≥50%). On univariate analysis, male gender, age, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking and diabetes mellitus were positively associated with a CAD-RADS score ≥3. The multivariate analysis showed that male sex, age, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and smoking were independently associated with obstructive CAD.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a significant association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and a higher coronary atherosclerotic burden assessed using CAD-RADS system in the Romanian population.

Keywords: CAD-RADS, cardiovascular risk factors, coronary artery disease, coronary CT angiography

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate the association of cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery disease (CAD) assessed using coronary CT angiography in Romania.

We quantified the coronary artery stenosis using the Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System classification, the newest, standardised method for reporting CAD.

The patients were recruited from a single centre; therefore, the study population was relatively small.

Another limitation is the design of the study: a cross-sectional, retrospective one.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Even though CAD mortality rates have declined since 1980s, it still accounts for approximately one-third of all deaths of individuals aged over 35 years old.1 2

It is well known that atherosclerosis is the underlying cause of cardiovascular diseases, and multiple risk factors augment the atherosclerotic process. These risk factors include non-modifiable ones such as age and sex and modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus and smoking.3–7 Studies suggest that the majority of patients with CAD have at least one modifiable risk factor, and their presence has an impactful role in the progression of CAD.8 9 Many risk-scoring systems have been developed such as Framingham and SCORE (Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation: High & Low cardiovascular Risk Charts) which are based on the presence of various traditional cardiovascular risk factors.10 11 Assessment of comorbidities and lifestyle together with basic laboratory investigations are recommended as step 2 and step 3 in the approach of patients with angina and suspected CAD.12 After identifying the potential cardiovascular risk factors and establishing the pretest probability and clinical likelihood of coronary artery disease, the next step is to select the appropriate tests for the diagnosis of CAD.12

With the recent advancements made in medical technology, coronary CT angiography (CCTA) has rapidly evolved into one of the most highly accurate methods for diagnosis and evaluation of CAD. It is a unique non-invasive test which can provide direct and accurate visualisation of the coronary vessel lumen, being able to quantify the presence and extent of coronary stenosis and to assess the characteristics of coronary atherosclerotic plaques.13

In the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes, CCTA has been categorised as class I recommendation for diagnosing CAD in symptomatic patients in whom obstructive CAD cannot be excluded by clinical assessment alone. Also, it can be considered as an alternative investigation to invasive angiography if another non-invasive test is equivocal or non-diagnostic.12

In 2016, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography published the Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS) grading system, which is a standardised reporting method of CCTA results. This is meant to facilitate communication of the results along with suggestions for consecutive management of the patients. The grading system ranges from 0 to 5, where CAD-RADS 0 score means a complete absence of stenosis and CAD-RADS 5 represents total occlusion of at least one coronary segment.14

Among European countries, Romania is one of the leading countries regarding the cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality burden, having the second highest standardised death rate caused by ischaemic heart disease.15 Also, the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors is relatively high in our country. Romania is on the fourth place in Europe concerning raised blood pressure, on the eighth place regarding the presence of diabetes mellitus16 17 and an increasing trend in the incidence of obesity.18

The aim of this study is to evaluate the association between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and CAD evaluated using the CAD-RADS score in the Romanian population.

Methods

Study population

We retrospectively reviewed 674 consecutive patients who underwent CCTA between January 2017 and August 2018 in our institution. The indications for CCTA were: atypical angina, typical angina with an inconclusive stress test, patients with intermediate/high risk for major cardiac events. The exclusion criteria included: previously known CAD, defined as prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (n=91), cardiac CT for other than evaluation of possible CAD (n=85), significant arrhythmias compromising imaging quality (n=23). Besides these exclusion criteria, patients with renal failure, documented contrast allergy or pregnant women did not perform the CT examination. Finally, 475 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Scan protocol

All CCTA scans were performed with a 64-sliced multidetector CT (Sensation 64, Siemens, Forchheim, Germany). The scanning parameters were: slices/collimation 64/0.6 mm, tube voltage 120 kv, 850 mAs, gantry rotation time 330 ms, pitch 0.2, effective slice thickness 0.75 mm and reconstruction increment 0.4 mm. Patients with a heart rate >70 beats/min received premedication with oral beta-blockers 1 hour prior to the examination. Short-acting nitroglycerine sublingual spray was administered to all patients for coronary vasodilatation.

First, a non-contrast-enhanced scan was performed to assess the coronary artery calcium score (CACS), followed by the CCTA to evaluate the coronary artery lumen and to characterise the atherosclerotic plaques. A bolus of 80 mL of iodinated contrast medium was administered intravenously at 5 mL/s, followed by 40 mL of saline injected at the same rate. After the acquisition, the images were transferred to a dedicated workstation for postprocessing, which included multiplanar reconstructions, maximum intensity projections and volume rendering images.

Coronary artery analysis

All CCTA images were assessed by an experienced radiologist who was blinded to the study (LEP). CACS was calculated using a semiautomatically software, according to the Agatston method. Plaque composition was classified as: calcified, non-calcified or mixed, with calcified coronary plaque being defined as any structure with a density ≥130 HU.

Coronary atherosclerotic lesions were quantified for stenosis by visual estimation. We evaluated only the coronary segments with a diameter greater than 1.5 mm.

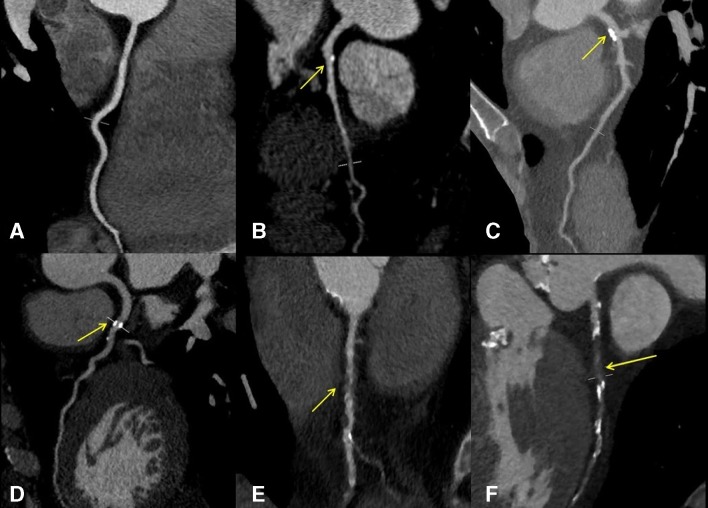

Every patient received a final CAD-RADS score based on the extent of coronary stenosis (figure 1). CAD-RADS score of 0 was assigned if there was a total absence of coronary plaques or stenosis. Minimal coronary stenosis between 1% and 24% was considered CAD-RADS 1. CAD-RADS score 2 was given when there was a mild stenosis between 25% and 49%. CAD-RADS score of 3 corresponded to a moderate stenosis between 50% and 69%. CAD-RADS score of 4 was assigned if there was a single coronary stenosis between 70% and 99% or if the left main artery was depicted with a stenosis of more than 50%. Also, CAD-RADS score of 4 was given in the situation of 3-vessel obstructive disease, when there were stenosis of more than 70% involving all the three coronary arteries (left anterior descending artery, circumflex artery and right coronary artery). If total occlusion was identified in at least one coronary segment, a CAD-RADS score of 5 was assigned.

Figure 1.

MPR images showing different degrees of coronary artery stenosis (yellow arrows): (A) normal RCA without any plaque or stenosis (CAD-RADS 0); (B) small calcified plaque in the proximal LAD with minimal luminal narrowing <25% (CAD-RADS 1); (C) calcified plaque in the proximal LAD with 25%–49% diameter stenosis (CAD-RADS 2); (D) semicircumferential calcified plaque in the proximal LAD with 50%–69% diameter stenosis (CAD-RADS 3); (E) non-calcified plaque in the proximal RCA with 70%–99% diameter stenosis (CAD-RADS 4); (F) total occlusion of proximal and mid LAD; calcified plaques above and beyond, it supports the diagnosis of chronic total occlusion (CAD-RADS 5). CAD-RADS, Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System; LAD, left anterior descending artery; MPR, multiplanar reconstruction; RCA, right coronary artery.

Obstructive CAD was defined as ≥50% stenosis of ≥1 coronary segments on CCTA.

Cardiovascular risk factors

Prior to CCTA, a detailed medical history with the risk factors was obtained from all patients. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or treatment with antihypertensive medications.19 Dyslipidaemia was defined as a total cholesterol level ≥5 mmol/L20 or treatment with lipid-lowering medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or the use of insulin or oral antidiabetic agents. Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2. Self-reported smoking status was obtained by a query regarding both current and previous smoking history. Classification of symptoms (typical angina, atypical angina, non-anginal pain) was judged by cardiologists using patient interviews conducted prior to the CT examination.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as means±SD, those with non-normal distribution as median with IQR. Normality was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Differences between CAD-RADS groups were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. Whenever the distribution of continuous data was not normal, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison.

Cardiovascular risk factors that showed a significant association with the CAD-RADS score were included in multivariable logistic regression analysis to evaluate their simultaneous influence. Through logistic regression analysis, independent relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and obstructive CAD (CAD-RADS score ≥3) was identified.

For all comparisons, a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software (MedCalc for Windows, V.14.8, MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Patient and public involvement

There was no involvement of patients and/or public in this study.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

The clinical and angiographic characteristics of our study population according to the CAD-RADS classification are shown in the online supplementary table 1. Among the 475 patients included in this study, the mean age was 57.8±13.2 years and the majority of them were female: 54.4%. There was a high prevalence of patients both with hypertension (74.5%) and dyslipidaemia (69.7%). The percentage of patients with diabetes was relatively small, with only 19.3% individuals having this condition. Smoking was reported among 46.3% of the study group. The majority of the patients were symptomatic, 72.6% presenting with either typical or atypical angina.

bmjopen-2019-031799supp001.pdf (65.6KB, pdf)

When we classified the patients according to the CAD-RADS score, 177 of them had CAD-RADS score=0, 99 patients had CAD-RADS score=1 while 80 patients CAD-RADS score=2. A percentage of 14.1% of people included in this study were diagnosed with CAD-RADS 3 score. Finally, 9.3% patients had severe stenosis, with a CAD-RADS score of 4 and 8 patients had total occlusion of a coronary segment (CAD-RADS score=5).

Patient gender, age, the presence of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus as well as clinical presentation and coronary artery calcium score were significantly different across CAD-RADS scores (p<0.0001 for all comparisons) (see online supplementary table 1). However, our results did not reveal any association between obesity and different CAD-RADS scores (p=0.63) (see online supplementary table 1).

CAD-RADS score and multiple cardiovascular risk factors

Using the cardiovascular risk factors mentioned above, we tested if there is any association regarding their presence and obstructive coronary artery disease, defined as coronary stenosis ≥50% and equivalent with a CAD-RADS score ≥3 (table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis for the association between cardiovascular risk factors and obstructive CAD classified using CAD-RADS categories

| Variable | Value | CAD-RADS score 0–2 (stenosis <50%) | CAD-RADS score 3–5 (stenosis ≥50%) | P value |

| Age | 55.41±13.11 | 63.10±10.55 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 142 (39.2%) | 75 (63.0%) | ||

| Female | 214 (60.1%) | 44 (37.0%) | ||

| Hypertension | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 242 (68.0%) | 112 (94.1%) | ||

| No | 114 (32.0%) | 7 (5.9%) | ||

| Dyslipidaemia | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 224 (62.9%) | 107 (89.9%) | ||

| No | 132 (37.01%) | 12 (10.1%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | =0.003 | |||

| Yes | 58 (16.3%) | 34 (28.6%) | ||

| No | 298 (83.7%) | 85 (71.4%) | ||

| Obesity | =0.93 | |||

| Yes | 151 (42.4%) | 50 (42.0%) | ||

| No | 205 (57.6%) | 69 (58.0%) | ||

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 145 (40.7%) | 75 (63.0%) | ||

| No | 211 (59.3%) | 44 (37.0%) | ||

| CACS | 0.4 (0–39.5) | 433.0 (182.4–924.8) | <0.001 |

Results are presented as mean±SD, number (%) or median (25th–75th percentile).

CACS, Coronary Artery Calcium Score; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAD-RADS, Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System.

Our results show that a CAD-RADS score between 0 and 2 was more frequent in younger patients, with a mean age of 55.41±13.11 years in this subgroup, while patients with CAD-RADS score ≥3 had a higher mean age of 63.1±10.55 years (table 1). Regarding gender, patients with CAD-RADS scores higher than 3 were more frequently male. The majority of the female patients (82.9%) received a CAD-RADS score of 0, 1 or 2 (table 1).

Our findings indicated a positive association between systolic hypertension and CAD-RADS score, with over 90% of the patients with moderate/severe stenosis (CAD-RADS ≥3) being hypertensive (table 1). Moreover, based on our results, patients with CAD-RADS scores ≥3 had a greater frequency of dyslipidaemia, with more than 85% patients in these categories being also dyslipidaemic (table 1).

Furthermore, the proportion of smokers was larger among patients identified with higher CAD-RADS scores: almost two-thirds of the patients who received a CAD-RADS score ≥3 admitted the use of cigarettes (table 1). On the other hand, in the CAD-RADS groups of 0, 1 and 2, the percentage of the smokers was less than 50% (table 1).

Regarding the association between diabetes mellitus and CAD-RADS score, our results show increasing per cents of diabetic individuals proportional with higher CAD-RADS scores: from 16.3% of patients with diabetes and CAD-RADS scores of 0–2% to 28.6% of patients with diabetes and CAD-RADS scores ≥3 (table 1). However, the percentage of patients with obesity patients did not differ significantly among different CAD-RADS groups (table 1).

Multivariable analysis

According to the multivariable analysis, male sex, age, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and smoking remained independently associated with obstructive CAD defined as CAD-RADS score ≥3 (table 2). Men had more than three times higher odds of developing significant coronary stenosis. The OR for coronary stenosis ≥50% was approximately 3.5-fold greater in individuals with hypertension. Our results showed that having dyslipidaemia significantly increased the odds of moderate/severe coronary stenosis by more than 2.5 times. Last but not least, smoking was associated with increased odds of having CAD-RADS score ≥3 by approximately two times.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for the association between cardiovascular risk factors and obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD-RADS score ≥3)

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Male sex | 3.136 (1.841 to 5.341) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.063 (1.036 to 1.090) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.493 (1.444 to 6.251) | 0.006 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.648 (1.283 to 5.466) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.207 (0.698 to 2.088) | 0.501 |

| Smoking | 2.112 (1.236 to 5.466) | 0.006 |

CAD-RADS, Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System.

Discussion

Romania is one of the high cardiovascular risk European countries according to data from the last ESC guideline for prevention of CVD.3 There are only a limited number of national epidemiological studies which estimate the prevalence and future trends of cardiovascular risk factors in the Romanian population.21–25 The latest study from 2017, Sephar III, shows an increasing trend regarding the majority of cardiovascular risk factors in our population.23 The prevalence of hypertension increased from 40.4% in 2011 to 45.1% in 2016.22 23 Moreover, the percentage of Romanians diagnosed with dyslipidaemia is alarmingly high, reaching 77.3% in 2016, with 53.4% newly diagnosed cases.23 Furthermore, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, another important risk factor for coronary artery disease, is 12.4%,24 a relatively high percentage that puts Romania on the eighth place in Europe regarding this medical condition.16 Overweight and obesity represent another medical issue encountered in our country. Both PREDATORR (PREvalence of DiAbeTes mellitus, prediabetes, overweight, Obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia and chronic kidney disease in Romania) and SEPHAR III (Study for the Evaluation of Prevalence of Hypertension and Cardiovascular Risk in Romania III) studies23 25 reported a prevalence of over 30% of patients with obesity based on BMI index, similar to the data from WHO database which shows an increasing trend of obesity in our country over the last 40 years.18 Last but not least, smoking can be considered another cause for the high incidence of cardiovascular disease in our country. Even if there is a decreasing trend regarding this habit in our country, Romania still occupies one of the leading places in European Union, with 28% of individuals reporting the use of cigarettes, a number higher than the average European percentage: 26%.26 According to the data by the National Institute for Public Health in Romania, tobacco is attributed to 16.3% CVD-related deaths in Romania.27

In Europe, Romania records one of the greatest incidences of cardiovascular diseases, according to the latest statistics offered by EuroStat in 2018.15 Our country occupies the second place in Europe regarding the per cent of total deaths caused by diseases of the circulatory system.15 Concerning the standardised death rates caused by ischaemic heart disease, Romania is also one of the leading countries, being on the sixth and fifth place in deaths of men and women, respectively.15

CAD-RADS is a standardised radiological reporting system dating since 2016, and there are only a few studies published in the area of cardiac imaging using the CAD-RADS score.28–32 It is used to quantify coronary artery stenosis in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease to provide a basis for further investigation, diagnosis, management and treatment, substantially reducing human error and improving data integrity.14

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one to evaluate the association between multiple associations of cardiovascular risk factors and the severity of coronary artery disease assessed on CCTA and evaluated using CAD-RADS classification in the Romanian population.

The association between cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular events was first demonstrated by the Framingham study through an epidemiological approach.33 The INTERHEART study showed that the cumulative effect of risk factors increased the risk of CAD, especially of myocardial infarction worldwide, in both sexes and all ages worldwide.34

Our research reports that male sex, age, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and smoking are significantly associated with obstructive CAD defined as CAD-RADS score ≥3, with the prevalence being increased by a cumulative effect on them.

Male sex and age are well-known risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis, being used in prediction models for the estimation of pretest probability of developing coronary artery disease.12 35 Among medical risk factors, our study showed that hypertension and dyslipidaemia were positively associated with CAD-RADS score ≥3 in both univariate and multivariable analyses. Our results are in concordance with the latest data from the European Heart Network which shows that systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol levels are the determinants with the greatest contribution to CVD mortality.17 Also, these two factors are included in the widely used SCORE charts (3), and there are many clinical models that add them for increasing the probability of obstructive CAD.36–39

Our multivariable analysis did not found an association between diabetes mellitus and obstructive CAD, one possible explanation being that only 19.3% of our study group had diabetes as their comorbidity.

Also, we did not find a direct association between obesity and coronary artery burden defined by CAD-RADS score. Our study is in concordance with Medakovic et al 40 and Dores H et al.41 According to Dores H et al, obesity assessed by BMI can be an indicator of the presence of CAD but not necessarily associated with its severity.41 They also described an ‘obesity paradox’ with better outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions at patients with a higher BMI.41 One hypothesis for this paradox is that patients with obesity tend to be diagnosed at an earlier age and stage of CAD, therefore having lower morbidity and mortality rates.42 43 Another potential reason for better outcomes of patients with obesity compared with those of underweight ones is that the latter group is more likely to have postprocedural complications due to excessive anticoagulation which is usually not weight adjusted.44 45 Moreover, underweight patients usually have more concomitant comorbidities which lead to worse prognosis.46 Another theory is that obesity is associated with higher amounts of lean mass and which can have a protective effect when not associated with increased systemic inflammation.47

Finally, our findings show that smoking is an independent risk factor for the presence of obstructive coronary disease, this being also one of the behavioural factors with the highest contribution for CVD mortality and morbidity rates across Europe.17

Limitations of the study

Our study has several limitations, the most important one being the fact that it is a retrospectively conducted one. Secondary, our results were confined to the experience of a single medical centre, and the findings of this study were based on a relatively small patient population. Regarding the risk factors, dyslipidaemia was not analysed by fractions of the cholesterol: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Also, we did not analyse other additional risk factors like alcohol use, physical activity, anthropometric measurements or C-reactive protein levels. Taking the retrospective approach into consideration, our research assess only the association between tradionally known cardiovascular risk factors and coronary stenosis evaluated by CAD-RADS score and does not assess the incidence of major cardiac events after performing the CT angiography.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that there is a significant association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and a higher coronary atherosclerotic burden assessed using CAD-RADS score in the Romanian population. Considering CAD as a priority for Romanian healthcare system, our study provides an overview of imaging and clinical characteristics of CAD and their association, offering valuable information for both cardiologists and radiologists to improve the management of the patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @0000-0003-2769-9643

Contributors: Conception (constructing the idea for research): LEP, MMB. Design (planning methodology to reach the conclusion): LEP, DSF, AL, RAR. Supervision (organising and supervising the course of the project): LEP, MMB, AM. Data collection and processing: RAR, CS, CC, CGM, BP. Analysis and interpretation: BP, DSF. Literature review: BP, CS, CC, CGM. Writing of the manuscript: LEP, BP, CC, CGM. Critical review: AM, AL, DSF, MMB.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of University of Medicine and Pharmacy ‘Iuliu Hatieganu’ Cluj-Napoca (455/19.12.2018) and University of Medicine and Pharmacy Targu Mures (272/21.11.2018). The Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective, HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant study and waived written informed consent. (1339/25.09.2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale C, et al. . European Society of cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2017. Eur Heart J 2018;39:508–79. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, et al. . Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980 to 2010: the global burden of disease 2010 study. Circulation 2014;129:1483–92. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. . 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rivera JJ, Nasir K, Cox PR, et al. . Association of traditional cardiovascular risk factors with coronary plaque sub-types assessed by 64-slice computed tomography angiography in a large cohort of asymptomatic subjects. Atherosclerosis 2009;206:451–7. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. . Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1·25 million people. The Lancet 2014;383:1899–911. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60685-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pekkanen J, Linn S, Heiss G, et al. . Ten-Year mortality from cardiovascular disease in relation to cholesterol level among men with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1700–7. 10.1056/NEJM199006143222403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenland P, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2003;290:891–7. 10.1001/jama.290.7.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canto JG, Kiefe CI, Rogers WJ, et al. . Number of coronary heart disease risk factors and mortality in patients with first myocardial infarction. JAMA 2011;306:2120–7. 10.1001/jama.2011.1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, et al. . Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2007;115:2722–30. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D'Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. . General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 2008;117:743–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conroy R, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the score project. Eur Heart J 2003;24:987–1003. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00114-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2019;100 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mangla A, Oliveros E, Williams KA, et al. . Cardiac imaging in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Curr Probl Cardiol 2017;42:316–66. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cury RC, Abbara S, Achenbach S, et al. . CAD-RADSTM coronary artery disease – reporting and data system. An expert consensus document of the Society of cardiovascular computed tomography (SCCT), the American College of radiology (ACR) and the North American Society for cardiovascular imaging (NASCI). endorsed by the American College of cardiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2016;10:269–81. 10.1016/j.jcct.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eurostat Available: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php/Cardiovascular_diseases_statistics

- 16. International Diabetes Federation IDF diabetes atlas. 8th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org [Google Scholar]

- 17. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics , 2017. Available: http://www.ehnheart.org/images/CVD-statistics-report-August-2017.pdf

- 18. World Health Organization Available: http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/ncd/risk_factors/obesity/atlas.html

- 19. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. . 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–104. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. HeartScore Available: http://www.heartscore.org/en_GB/

- 21. Dorobantu M, Darabont RO, Badila E, et al. . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Romania: results of the SEPHAR study. Int J Hypertens 2010;2010:1–6. 10.4061/2010/970694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dorobanţu M, Darabont R, Ghiorghe S, et al. . Profile of the Romanian hypertensive patient data from SEPHAR II study. Rom J Intern Med 2012;50:285–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dorobantu M, Tautu O-F, Dimulescu D, et al. . Perspectives on hypertensionʼs prevalence, treatment and control in a high cardiovascular risk East European country. J Hypertens 2018;36:690–700. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mota M, Popa SG, Mota E, et al. . Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and prediabetes in the adult Romanian population: PREDATORR study. J Diabetes 2016;8:336–44. 10.1111/1753-0407.12297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Popa S, Moţa M, Popa A, et al. . Prevalence of overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome and atypical cardiometabolic phenotypes in the adult Romanian population: PREDATORR study. J Endocrinol Invest 2016;39:1045–53. 10.1007/s40618-016-0470-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. European Commission Available: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/surveyKy/2146

- 27. Simionescu M, Bilan S, Gavurova B, et al. . Health policies in Romania to reduce the mortality caused by cardiovascular diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:3080 10.3390/ijerph16173080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xie JX, Cury RC, Leipsic J, et al. . The coronary artery Disease-Reporting and data system (CAD-RADS): prognostic and clinical implications associated with standardized coronary computed tomography angiography reporting. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:78–89. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams MC, Moss A, Dweck M, et al. . Standardized reporting systems for computed tomography coronary angiography and calcium scoring: a real-world validation of CAD-RADS and CAC-DRS in patients with stable chest pain. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2019. 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodriguez-Granillo GA, Carrascosa P, Goldsmit A, et al. . Invasive coronary angiography findings across the CAD-RADS classification spectrum. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;35:1955–61. 10.1007/s10554-019-01654-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Rosendael AR, Shaw LJ, Xie JX, et al. . Superior risk stratification with coronary computed tomography angiography using a comprehensive atherosclerotic risk score. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019;12:1987–97. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Szilveszter B, Kolossváry M, Karády J, et al. . Structured reporting platform improves CAD-RADS assessment. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017;11:449–54. 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham study. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1951;41:279–86. 10.2105/AJPH.41.3.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. . Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. The Lancet 2004;364:937–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Genders TSS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, et al. . A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation, updating, and extension. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1316–30. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Genders TSS, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MGM, et al. . Prediction model to estimate presence of coronary artery disease: retrospective pooled analysis of existing cohorts. BMJ 2012;344:e3485 10.1136/bmj.e3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reeh J, Therming CB, Heitmann M, et al. . Prediction of obstructive coronary artery disease and prognosis in patients with suspected stable angina. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1426–35. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Versteylen MO, Joosen IA, Shaw LJ, et al. . Comparison of Framingham, PROCAM, score, and diamond Forrester to predict coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2011;18:904–11. 10.1007/s12350-011-9425-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jensen JM, Voss M, Hansen VB, et al. . Risk stratification of patients suspected of coronary artery disease: comparison of five different models. Atherosclerosis 2012;220:557–62. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medakovic P, Biloglav Z, Padjen I, et al. . Quantification of coronary atherosclerotic burden with coronary computed tomography angiography: adapted Leaman score in Croatian patients. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;34:1647–55. 10.1007/s10554-018-1376-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dores H, de Araújo Gonçalves P, Carvalho MS, et al. . Body mass index as a predictor of the presence but not the severity of coronary artery disease evaluated by cardiac computed tomography. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:1387–93. 10.1177/2047487313494291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Kojima S, et al. . Impact of body mass index on in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 2007;72:521–5. 10.1253/circj.72.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mehta L, Devlin W, McCullough PA, et al. . Impact of body mass index on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:906–10. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gruberg L, Weissman NJ, Waksman R, et al. . The impact of obesity on the short-term andlong-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the obesity paradox? J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:578–84. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01802-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Powell BD, Lennon RJ, Lerman A, et al. . Association of body mass index with outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:472–6. 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)03252-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xia JY, Lloyd-Jones DM, Khan SS. Association of body mass index with mortality in cardiovascular disease: new insights into the obesity paradox from multiple perspectives. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2019;29:220–5. 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carbone S, Canada JM, Billingsley HE, et al. . Obesity paradox in cardiovascular disease: where do we stand? Vasc Health Risk Manag 2019;15:89–100. 10.2147/VHRM.S168946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031799supp001.pdf (65.6KB, pdf)