Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association between health literacy (HL) and quality of life (QOL) among cancer survivors in China.

Design

Cross-sectional study in China.

Setting and participants

This is a cross-sectional observational study of 4589 cancer survivors aged 18 years and older from the Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club. Participants were enrolled and completed the questionnaires between May and July 2017.

Measurement

HL was assessed by three established screening questions and QOL was evaluated using the simplified Chinese version of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Core 30 items. Answers to all questionnaires were collected through face-to-face interviews or through self-administered questionnaires for literate participants. Participants were excluded if they did not answer any one of the HL questions. Baseline characteristics were compared by levels of HL using χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal continuous variables. The item response theory (IRT) was used to evaluate the existing measure of HL. Linear regression and logistic regression models were used to investigate the association between HL and QOL. SAS V.9.4 and MULTILOG V.7.03 were used in the analysis.

Results

There were 4589 participants included in the study. The calculated results of IRT scale parameters of HL entries indicate that the entries have better discrimination and difficulty. Of the 4589 respondents, 159 (3.5%) had low HL. After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, treatment regimen and years with cancers, for each one-point decrement in HL score the QOL score increased by 2.07 (p<0.001). Cancer survivors with low HL were less likely than those with adequate HL to achieve better QOL. In logistic regression, low HL was independently associated with poor QOL (adjusted OR, 2.81; 95% CI 1.94 to 4.06; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Low HL was independently associated with poor QOL among cancer survivors of the Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club.

Keywords: Health Literacy, 3 Brief Screening Questions, Quality of Life, Cancer Survivors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the few studies to use three brief screening questions to evaluate health literacy among Chinese cancer survivors, instead of questionnaires with long and complex questions, which are not suitable for use in clinical routine practice, and to explore the relationship between health literacy and quality of life.

The item response theory was applied to evaluate whether a summed unidimensional health literacy scale could be used.

Causal inferences could not be drawn due to the cross-sectional design of the study.

The proportion of participants with high health literacy might be overestimated, and those with low literacy are sometimes excluded from the study due to illiteracy.

Introduction

Health literacy (HL) is an evolving concept. As defined by the National Library of Medicine,1 HL is ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions’. It means more than simply the ability to ‘read pamphlets’, ‘make appointments’, ‘understand food labels’ or ‘comply with prescribed actions’ from a doctor.2 Higher levels of HL within populations yield social benefits,3 4 and HL is an important factor in ensuring significant health outcomes.5 6 Previous studies indicated that poor or limited HL can make it difficult for patients to function effectively in the healthcare system, and that it is associated with several negative outcomes, such as poor health status, decreased comprehension of medical information, lack of engagement with doctors, higher cost of healthcare and so forth.7 8

Cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide,9 and its economic impact is increasing. China had a lower incidence rate of cancer compared with Western countries; however, its incidence has increased with a sharp slope in recent decades.10 11 Patients nowadays are diagnosed using advanced diagnostic techniques and cured by modern therapeutic methods, extending the lifespan of patients with cancer and resulting to more attention being paid to the quality of life (QOL) during their survival years.12

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) refers to individuals’ subjective assessment of well-being and ability to perform social roles, and has been accepted as a health indicator in medical settings, such as clinical interventions, treatments and health surveys.13 Studies evaluating the relationship between HL and HRQOL among cancer survivors have produced mixed results. A longitudinal, population-based study conducted in the Netherlands between 2000 and 2009 (n=1643, response rate 83%) showed that low subjective HL was associated with worse QOL among colorectal cancer survivors registered in the Eindhoven Cancer Registry.14 A study by Hahn et al 15 conducted among 420 outpatients with cancer enrolled at five cancer centres in the Chicago area indicated that low literacy is not an independent risk factor for poor HRQOL. There are other various studies on different populations which reported different results, and few similar studies conducted in less developed countries such as China.

A growing body of research measures HL with long and complex questions, which are not suitable for use in clinical routine practice.16 Thus, this study adopted the questions from Chew’s Brief Health Literacy Screening tool, which has established validity for evaluating subjective functional HL.17 The scale has three questions only and can be easily and handily implemented in busy clinical settings. QOL was chosen as the primary outcome of interest because it can fully reflect the feeling and physical recovery of patients. It has also been increasingly used as a comprehensive health indicator in clinical treatments and interventions.18 19 QOL can be used as one of the indicators of efficacy of different therapeutic measures and the combination of QOL and clinical curative effect observation index can help choose a more suitable treatment for patients. The simplified Chinese version of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Core 30 items (EORTC QLQ-C30) has been widely used to assess QOL among patients with cancer and has well-documented validity and reliability in various populations.20 21

Therefore, using a population-based survey, this study aims to evaluate the association between HL and QOL in a sample of cancer survivors (breast, colorectal, lung, stomach, thyroid and so on) from the Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club using three brief screening questions. We hypothesise that higher HL levels would be associated with better physical and mental well-being. Isolating the independent contribution of HL towards cancer survivors’ QOL would have important clinical and public health implications, and would help relieve the conflict between the complexity of cancer care and health deficits, and ultimately improve patients’ HRQOL.22

Methods

Design and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted from May to July 2017. All participants were recruited from the Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club, a non-governmental self-help mutual aid organisation with 20 branch offices, 175 community block groups and more than 13 000 members. The present study covered 16 districts in Shanghai (Huangpu, Pudong, Xuhui, Changning, Putuo, Hongkou, Yangpu, Minhang, Baoshan, Jiading, Jinshan, Songjiang, Qingpu, Fengxian, Chongming and Jingan).

Participants

All participants of the study were cancer survivors from the Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club. The following were the inclusion criteria for study enrolment: (1) at least 18 years old, (2) have a pathological diagnosis of cancer, (3) able to independently participate in the cancer rehabilitation club, (4) willing to provide written informed consent, and (5) no cognitive impairment or psychotic disorder. Information leaflets that describe the scope and purpose of the study were given to patients, and written informed consent forms were obtained ahead of the investigation from those who met the inclusion criteria. A box of eggs was offered as gifts for their participation. The investigators, who were all students of Fudan University, were trained and field investigation was conducted. Answers to questionnaires were collected through face-to-face interviews with the help of well-trained fieldworkers or through self-administered questionnaires for literate participants. There were 4713 cancer survivors surveyed, and 4610 responded. Excluding incomplete questionnaires (questionnaires with all three questions not answered are considered incomplete), we obtained a total of 4589 valid questionnaires.

Measures

HL was assessed using three established screening questions and was categorised as adequate or inadequate.17 23–25 The following were the questions: ‘How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?’, ‘How confident are you filling out forms by yourself’ and ‘How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty reading hospital materials?’ Each question was scored by participants on a 5-point scale. HL was evaluated as a continuous and dichotomous variable. Based on a previous study,16 scores were summed, and participants were categorised as low HL if their total score were higher than 10 and adequate HL if 10 or lower.

QOL was assessed using the simplified Chinese version of EORTC QLQ-C30, which incorporates nine multi-item scales26—five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social functioning), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain and nausea/vomiting) and a global health status/QOL scale—and six single-item scales (dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties). The psychometric properties of the questionnaire had previously been evaluated.27 Scale scores were calculated by averaging the items within the scales and transforming the average scores linearly. All of the scales range in scores from 0 to 100. A high score on a functional scale represents a high/healthy level of functioning, whereas a high score on a symptom scale or item represents a high level of symptomatology or problems. For more details on the scoring procedures, see the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual.28 Participants were classified as having good QOL if their scores were higher than 50 and poor QOL if lower than 50.

Other variables

The covariates were age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, educational level, marital status (married vs single or divorced/widowed), insurance status, years with cancer, smoking habit, alcohol use, physical activity, treatment regimen, district, body mass index (BMI) and history of coexisting illnesses. Because coexisting illnesses may affect survivors’ QOL, we measured coexisting illnesses by asking cancer survivors whether they had ever been told by a physician that they had a chronic disease, including hypertension, hyperlipaemia, hyperuricaemia, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and diseases of the respiratory, digestive and skeletal systems. All covariates were determined at the time of the survey.

Statistical analysis

To determine whether a summed unidimensional HL scale could be used, the item response theory (IRT) was applied to evaluate the item parameter (discrimination parameter, threshold parameter), item characteristic curve and item information curve. Since the item responses were classified into ordered polytomous categories, the graded response model was used. For the participants answering only one or two of the three questions, the score for those questions was multiplied by 3 and 1.5, respectively.16

Baseline characteristics were compared across levels of HL using χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal continuous variables. Linear regression models were used to estimate the association between HL score and QOL after controlling for differences in participants’ characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, marriage, education, income, insurance status, years with cancer, number of chronic diseases, smoking habit, alcohol use, physical activity, treatment regimen, district and BMI. Logistic regression models were used to measure the independent relationship between HL and each of the QOL scales, while adjusting for other potentially confounding survivor characteristics.

IRT analyses were conducted using MULTILOG V.7.03. Other statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4. The null hypothesis was evaluated at a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development of the research question or in the design of the study.

Results

Among 4713 cancer survivors surveyed, 4610 responded, yielding a 97.81% response rate. For 4589 of the 4610 participants, at least one HL question was available in the survey; these participants composed our study sample, providing 99.5% valid questionnaires.

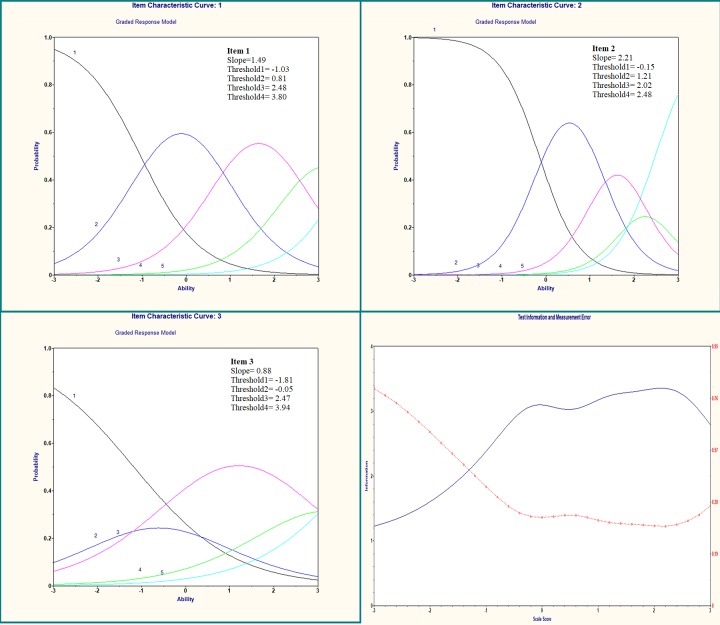

The summed HL scale was measured using all three HL questions. The correlations of single items to the total were 0.73, 0.70 and 0.75 for questions 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Figure 1 shows the IRT models and test information for the total sample and illustrated the implications of the item parameters for the response probabilities for the different levels of HL. All items had high discrimination parameters, except for item 3, ‘How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty reading hospital materials?’ which had moderate discrimination (α=0.88) but still satisfied the condition α>0.75. The difficulty parameters (threshold) increased monotonically across rating scale categories for all items, ranging from −1.81 to 3.94, indicating that the three HL questions discriminated well. Among the 4589 participants, the mean HL score was 6.3 (range, 3–15). As table 1 shows, 159 (3.5%) participants had low HL (HL score, 11–15). Participants with low HL were more likely than participants with adequate HL to be older, to have received only middle school education or lower, and to have had light physical activity.

Figure 1.

Item characteristic curve and test information curve for the three established screening questions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents stratified by level of health literacy*

| Characteristics | Total (N=4589) | Level of health literacy | P value | |

| Adequate (n=4430) | Inadequate (n=159) | |||

| Age, mean (Quartile 1, Quartile 3), years | 62.0 (57.04, 66.53) | 62.0 (57.00, 66.53) | 62.52 (58.37, 68.39) | 0.0485 |

| Years with cancers, mean (Quartile 1, Quartile 3) | 6.09 (3.50, 10.50) | 6.09 (3.50, 10.50) | 5.92 (3.50, 10.58) | 0.6258 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.9424 | |||

| Male | 1057 (23.03) | 1020 (96.50) | 37 (3.50) | |

| Female | 3532 (76.97) | 3410 (96.55) | 122 (3.45) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.8644 | |||

| Hanzu | 4544 (99.28) | 4386 (96.52) | 158 (3.48) | |

| Marriage, n (%) | 0.2192 | |||

| Single | 129 (2.81) | 121 (93.80) | 8 (6.20) | |

| Married/cohabitation | 3989 (86.93) | 3853 (96.61) | 136 (3.41) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 471 (10.226) | 456 (96.82) | 15 (3.18) | |

| Annual income, ¥, n (%) | 0.0534 | |||

| <5000 | 4134 (91.89) | 3987 (96.44) | 147 (3.56) | |

| ≥5000 | 365 (8.11) | 359 (98.36) | 6 (1.64) | |

| Family income, ¥, n (%) | 0.8296 | |||

| <5000 | 3086 (70.07) | 2979 (96.53) | 107 (3.47) | |

| ≥5000 | 1318 (29.93) | 1274 (96.66) | 44 (3.34) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.0003 | |||

| Middle school or lower | 4021 (87.62) | 3867 (96.17) | 154 (3.83) | |

| High school or college | 568 (12.38) | 563 (99.12) | 5 (0.88) | |

| Insurance status, n (%) | 0.8159 | |||

| Uninsured | 645 (15.55) | 623 (96.59) | 22 (3.41) | |

| Medicare | 3504 (84.45) | 3378 (96.40) | 126 (3.60) | |

| Treatment regimen, n (%) | 0.2753 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 661 (14.44) | 641 (96.97) | 20 (3.03) | |

| Radiotherapy | 74 (1.62) | 68 (91.89) | 6 (8.11) | |

| Operation | 931 (20.34) | 902 (96.89) | 29 (3.11) | |

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 162 (3.54) | 155 (95.68) | 7 (4.32) | |

| Chemotherapy, radiotherapy and operation | 897 (19.59) | 870 (96.99) | 27 (3.01) | |

| Chemotherapy and operation | 1658 (36.22) | 1594 (96.14) | 64 (3.86) | |

| Biotherapy | 69 (1.51) | 66 (95.65) | 3 (4.35) | |

| Number of chronic diseases, n (%) | 0.3564 | |||

| 0 | 1238 (26.98) | 1203 (97.17) | 35 (2.83) | |

| 1–3 | 2735 (59.60) | 2634 (96.31) | 101 (3.69) | |

| >3 | 616 (13.42) | 593 (96.27) | 23 (3.73) | |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 0.5284 | |||

| Never | 3841 (83.70) | 3711 (96.62) | 130 (3.38) | |

| Former | 598 (13.03) | 573 (95.82) | 25 (4.18) | |

| Current | 150 (3.27) | 146 (97.33) | 4 (2.67) | |

| Current alcohol use, n (%) | 0.0637 | |||

| None | 4264 (92.92) | 4113 (96.46) | 151 (3.54) | |

| Light to moderate | 215 (4.69) | 213 (99.07) | 2 (0.93) | |

| Heavy | 110 (2.40) | 104 (94.55) | 6 (5.45) | |

| Body mass index†, n (%) | 0.4593 | |||

| <18.5 | 233 (5.16) | 229 (98.28) | 4 (1.72) | |

| 18.5–23.9 | 2342 (51.85) | 2258 (96.41) | 84 (3.59) | |

| 24.0–27.9 | 1546 (34.23) | 1492 (96.51) | 54 (3.49) | |

| ≥28.0 | 396 (8.77) | 380 (95.96) | 16 (4.04) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 0.0264 | |||

| None | 1038 (22.64) | 991 (95.47) | 47 (4.53) | |

| 1–4 times per week | 2493 (54.37) | 2406 (96.51) | 87 (3.49) | |

| ≥5 times per week | 1054 (22.99) | 1029 (97.63) | 25 (2.37) | |

*Data are shown as percentages unless otherwise indicated.

†Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres.

Table 2 presents the bivariate relationship between the predictors of QOL and cancer survivors’ global health status. HL score, age, sex, marriage, years with cancer, number of chronic diseases, smoking habit, alcohol use, physical activity, district and BMI were all associated with global health status. After adjusting for other potentially confounding factors, marriage, years with cancer and smoking habit were not significantly different among the levels of HL. For each one-point decrement in the HL score, the global health status value increased by 2.07 (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Relationship between survivors’ characteristics and QOL

| Predictor | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||

| Coefficient† | P value | Coefficient† | P value | |

| HL score | −2.11 | <0.0001 | −2.07 | <0.0001 |

| Age | −0.25 | <0.0001 | −0.16 | 0.0053 |

| Sex, female | −3.92 | <0.0001 | −5.02 | 0.0002 |

| Race/ethnicity | 2.10 | 0.5854 | 6.41 | 0.1819 |

| Marriage | −3.01 | 0.0051 | −2.14 | 0.0710 |

| Education | −0.28 | 0.6316 | −1.38 | 0.3190 |

| Annual income | 0.42 | 0.7664 | 0.81 | 0.6044 |

| Family income | −0.03 | 0.9694 | 0.53 | 0.5521 |

| Insurance status | −1.67 | 0.1263 | −0.09 | 0.9346 |

| Years with cancer (per year) | −0.23 | 0.0002 | −0.04 | 0.5401 |

| Number of chronic diseases | −5.79 | <0.0001 | −4.87 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking habit | 1.35 | 0.015 | −1.23 | 0.1210 |

| Alcohol intake | 3.38 | <0.0001 | 2.07 | 0.0240 |

| Physical activity | 4.07 | <0.0001 | 3.15 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment regimen | −0.004 | 0.985 | 0.16 | 0.4474 |

| District | 0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.48 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index | 1.14 | 0.0305 | 2.18 | <0.0001 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, income, education, insurance, years with cancer, treatment regimen, district, number of chronic diseases, smoking habit, alcohol use, physical activity and body mass index.

†All coefficients correspond to a change in QOL score for a unit change of each covariate.

HL, health literacy; QOL, quality of life.

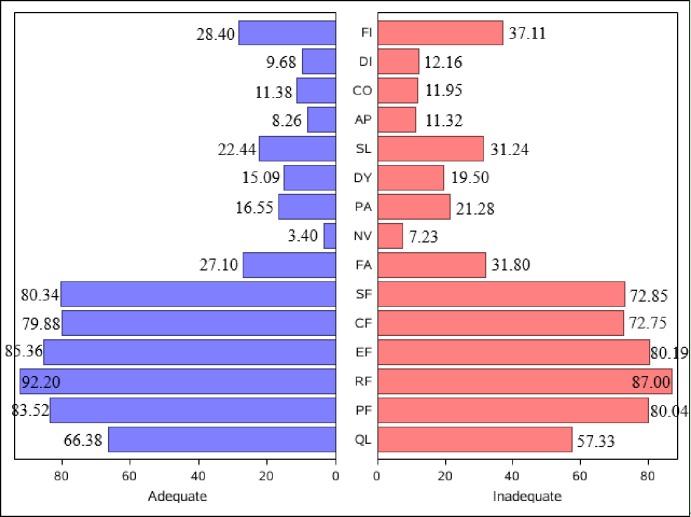

Cancer survivors with adequate HL were more likely to receive higher scores on the functional scale and lower scores on the symptom scale compared with those with low HL. According to a recommendation,29 a difference of more than five points on the 0–100 scale is considered a clinically important difference. As can be seen in figure 2, there was a clinically significant difference between survivors with adequate HL and survivors with low HL in terms of global health status (difference of adequate HL vs low HL (diff), 9.05), role function (diff: 5.2), emotional function (diff: 5.17), cognitive function (diff: 7.13), social function (diff: 7.49), insomnia (diff: −8.8) and financial difficulties (diff: −8.71).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted quality of life scores for cancer survivors with inadequate and adequate health literacy. AP, appetite loss; CF, cognitive function; CO, constipation; DI, diarrhoea; DY, dyspnoea; EF, emotional function; FA, fatigue; FI, financial difficulties; NV, nausea/vomiting; PA, pain; PF, physical function; QL, global health status; RF, role function; SF, social function; SL, insomnia.

Of the cancer survivors, 83% with adequate HL and 65% with low HL reported that they had good global health status (unadjusted OR, 2.75; 95% CI 1.97 to 3.84; p<0.001). After adjusting for confounders, cancer survivors with adequate HL were more likely to report better global health status (adjusted OR, 2.81; 95% CI 1.94 to 4.06; p<0.001) (table 3). The extent of the association between HL and other scales of QOL, including four functional scales (physical, emotional, cognitive and social functioning), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain and nausea/vomiting) and three single-item scales (insomnia, appetite loss and financial difficulties), was similar to that of global health status and all had statistical significance (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted OR of QOL for cancer survivors with inadequate vs adequate health literacy*

| QOL | Survivors with poor QOL | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Global health status | 788 | 2.81 (1.94 to 4.06) | <0.0001 |

| Physical function | 83 | 2.84 (1.18 to 6.87) | 0.0205 |

| Role function | 53 | 2.70 (0.94 to 7.80) | 0.0664 |

| Emotional function | 77 | 5.01 (2.37 to 10.58) | <0.0001 |

| Cognitive function | 128 | 4.07 (2.18 to 7.61) | <0.0001 |

| Social function | 250 | 3.59 (2.19 to 5.88) | <0.0001 |

| Fatigue | 425 | 2.63 (1.68 to 4.12) | <0.0001 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 52 | 5.39 (2.17 to 13.38) | 0.0003 |

| Pain | 296 | 2.37 (1.41 to 3.97) | 0.0011 |

| Dyspnoea | 152 | 1.86 (0.88 to 3.94) | 0.106 |

| Insomnia | 475 | 2.41 (1.56 to 3.74) | <0.0001 |

| Appetite loss | 91 | 3.84 (1.84 to 8.03) | 0.0003 |

| Constipation | 188 | 1.06 (0.45 to 2.46) | 0.8995 |

| Diarrhoea | 114 | 2.11 (0.95 to 4.71) | 0.0679 |

| Financial difficulties | 747 | 2.73 (1.88 to 3.97) | <0.0001 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, income, education, insurance, years with cancer, treatment regimen, district, number of chronic diseases, smoking habit, alcohol use, physical activity and body mass index.

QOL, quality of life.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that inadequate HL assessed by three brief screening questions was found in less than 1 in 25 cancer survivors from the Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club, and that inadequate HL was an independent predictor of poor QOL and was associated with a lower level of functioning and a higher level of symptomatology or problems. The observed association between HL and QOL is significant from a clinical and public health perspective. These findings highlight a potential target for interventions to improve the overall QOL of cancer survivors.

To our knowledge, only few studies had demonstrated an association between HL and QOL among cancer survivors in China using three brief screening questions. Previous research has used more complex and extensive questionnaires to measure HL, such as the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine,22 30 Cancer Health Literacy Test-30,31 Short-Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults5 32 33 and others, which are impractical for use in busy clinical settings. Despite differences in the nature of HL assessment techniques, our results are consistent with those of previous studies that identified inadequate HL as a risk factor for QOL among cancer survivors.5 14 34 Our results showing a higher adequate HL level are in contrast to those from other Chinese studies35 36 which found a lower adequate HL in the Chinese population. This might be because the participants we surveyed all came from Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club. The club37 firmly advocates ‘anti-cancer groups, beyond life’ and organises a variety of activities to make patients feel full confidence in their rehabilitation. Thus, participants of the club will have their HL levels gradually improved, which might be the reason why our results were higher than in other studies.

The results of this study showed that many factors were associated with QOL among cancer survivors, including HL score, age, sex, number of chronic diseases, alcohol intake, physical activity, district and BMI, which was almost in line with previous studies.38 Consistent HL score was found to be associated with QOL. The higher the HL score (indicating limited HL), the lower the QOL.34 Gender was found to be a determinant of QOL, with male participants being more likely to have poor QOL compared with female participants. The study also showed that older survivors reported higher QOL; there exists some research reporting that overall QOL increases with age.39 There was a strong association between QOL and chronic disease, with QOL being lower in survivors with chronic disease.40 Physical activity was found to be positively associated with QOL, and those living in urban areas were more likely to have better QOL than those living in rural areas. Survivors with higher BMI had higher overall QOL when controlling for confounders, which was slightly different from some studies conducted among women reported that higher BMI was associated with QOL.41 42

Additionally, a positive relationship between HL and scales of HRQOL existed regardless of how HL or HRQOL was operationalised (continuous or categorical). Our study showed that cancer survivors with adequate HL had nearly three times the odds of having better QOL than cancer survivors with inadequate HL, and the same trend could be found in other functional scales. In the symptom scales, those with adequate HL were more likely to have minor symptoms compared with those with limited HL. This is largely because the information needs and understanding of person living with chronic conditions are critical to optimal management.8 Kim et al 43 indicated that low HL among patients with prostate cancer may have hindered patients’ involvement in shared decision-making with physicians. Those who had inadequate HL may have difficulty in understanding medical information given by their providers, managing their treatment plan and adherence to cancer treatment regimens, resulting in exacerbated treatment-related symptoms,34 whereas those who had adequate HL have better chance of acquiring health information about the diseases, and understand doctors’ advice and adopthealthy lifestyles, such as drinking less alcohol and exercising regularly.

From a public health perspective, HL is an important factor in ensuring significant health outcomes.34 44 45 Inadequate HL may contribute to the disproportionate burden of cancer-related problems among disadvantaged populations. The United Nations The Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Ministerial Declaration of 2009 provided a clear mandate for action: ‘call for the development of appropriate action plans to promote health literacy’.2 The Ninth Global Conference was held in Shanghai, China in 2016 and addressed the determinants of health through good governance, healthy cities, HL and social mobilisation.2 Therefore, improving cancer survivors’ HL is an important target to improve their QOL.

Limitation

Several limitations should be considered in the interpretation of our findings. First, this was a cross-sectional study and causal inferences could not be drawn due to its cross-sectional design, and interventions should be conducted in further research. Second, we did not use the Chinese Health Literacy Scale and other complex scales to evaluate HL and the three brief questions may reflect other constructs. However, the three brief questions can be easily incorporated into clinical routine work and are useful in identifying high-risk patients. Third, this study may have good representativeness only among cancer survivors from Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club and may not be generalisable to non-members of this club.

Conclusions

In summary, inadequate HL, as evaluated by three brief screening questions, is independently associated with poor QOL among cancer survivors. Efforts should focus on developing and evaluating interventions to improve QOL among cancer survivors with inadequate HL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Furong Tang, Donghui Yu, Mengxue Yin and some other volunteers who contributed to this survey. We also wish to thank the thousands of cancer survivors who were willing to complete the survey.

Footnotes

JX and PW contributed equally.

Contributors: JX carried out the field investigation, participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. PW was in charge of the process of submission and revision of this paper. PW, QD, RuY, ReY and BL participated in the field investigation and data collection. JW and JY designed and coordinated the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved by the Committee of Public Health School of Fudan University (protocol number IRB#2017-05-0621).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kindig DA, Panzer AM, Nielsen-Bohlman L, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Vol. 15 National Academies Press, 2004. 389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization The mandate for health literacy. Available: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/health-literacy/en/ [Accessed 1 Feb 2018].

- 3. Eichler K, Wieser S, Brügger U. The costs of limited health literacy: a systematic review. Int J Public Health 2009;54:313–24. 10.1007/s00038-009-0058-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1027–30. 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schillinger D, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002;288:475–82. 10.1001/jama.288.4.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weiss BD, Hart G, McGee DL, et al. Health status of illiterate adults: relation between literacy and health status among persons with low literacy skills. J Am Board Fam Pract 1992;5:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jayasinghe UW, Harris MF, Parker SM, et al. The impact of health literacy and life style risk factors on health-related quality of life of Australian patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:68 10.1186/s12955-016-0471-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kugbey N, Meyer-Weitz A, Oppong Asante K. Access to health information, health literacy and health-related quality of life among women living with breast cancer: depression and anxiety as mediators. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1357–63. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. International Agency for Research on Cancer GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. Available: http://globocan.iarc.fr/ [Accessed 1 Feb 2018].

- 10. Grayson M. Breast cancer. Nature 2012;485:S49 10.1038/485S49a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keyghobadi N, Rafiemanesh H, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, et al. Epidemiology and trend of cancers in the province of Kerman: Southeast of Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16:1409–13. 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.4.1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghislain I, Zikos E, Coens C, et al. Health-Related quality of life in locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer: methodological and clinical issues in randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e294–304. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30099-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang H-M, Beyer M, Gensichen J, et al. Health-Related quality of life among general practice patients with differing chronic diseases in Germany: cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2008;8:246 10.1186/1471-2458-8-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Husson O, Mols F, Fransen MP, et al. Low subjective health literacy is associated with adverse health behaviors and worse health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors: results from the profiles registry. Psychooncology 2015;24:478–86. 10.1002/pon.3678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hahn EA, Cella D, Dobrez DG, et al. The impact of literacy on health-related quality of life measurement and outcomes in cancer outpatients. Qual Life Res 2007;16:495–507. 10.1007/s11136-006-9128-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peterson PN, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA 2011;305:1695–701. 10.1001/jama.2011.512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, et al. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:874–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu Z, Yang J. Health related quality of life: is it another comprehensive evaluation indicator of Chinese medicine on acquired immune deficiency syndrome treatment? J Tradit Chin Med 2015;35:600–5. 10.1016/s0254-6272(15)30146-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:622–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wan CH, Chen QM, Zhang CZ etc. Evaluation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 Chinese version of the cancer patient's quality of life measurement scale. J Pract Oncol 2005;04:353–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meng Q, Wan CH, Luo JH etc. Study on psychometrical characteristics of different scales among instruments measuring quality of [J]. Tumor 2011;31:245–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Song L, Mishel M, Bensen JT, et al. How does health literacy affect quality of life among men with newly diagnosed clinically localized prostate cancer? findings from the North Carolina-Louisiana prostate cancer project (PCaP). Cancer 2012;118:3842–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large Va outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:561–6. 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wallace LS, Cassada DC, Rogers ES, et al. Can screening items identify surgery patients at risk of limited health literacy? J Surg Res 2007;140:208–13. 10.1016/j.jss.2007.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 2004;36:588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–76. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang JW, Tang Z, JM Y, et al. QLQ-BR23 and EORTC+QLQ-C30 for measurement of the impact of rehabilitation exercise on quality of life in breast cancer patients. Fudan Univ J Med Sci 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual 2001.

- 29. Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. JCO 1998;16:139–44. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993;25:391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Echeverri M, Anderson D, Nápoles AM. Cancer health literacy Test-30-Spanish (CHLT-30-DKspa), a new Spanish-Language version of the cancer health literacy test (CHLT-30) for Spanish-speaking Latinos. J Health Commun 2016;21:69–78. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1131777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yehle KS, Plake KS, Nguyen P, et al. Health-Related quality of life in heart failure patients with varying levels of health literacy receiving telemedicine and standardized education. Home Healthcare Now 2016;34:267–72. 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, et al. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns 1999;38:33–42. 10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00116-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Halverson JL, Martinez-Donate AP, Palta M, et al. Health literacy and health-related quality of life among a population-based sample of cancer patients. J Health Commun 2015;20:1320–9. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yao H, Shi Q, Li Y. The current status of health literacy in China. China Population Today 2016:41. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang L, Peng S, University FM, et al. The status and influencing factors of health literacy among cancer patients. Nursing Journal of Chinese Peoples Liberation Army 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shanghai Cancer Rehabilitation Club, Shanghai Oriental Cancer Double Prevention Rehabilitation Guidance Center , 2012. Available: http://www.shcrc.cn/webs/intro.aspx [Accessed 1 Feb 2018].

- 38. Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, et al. Quality of life among long-term (⩾5years) colorectal cancer survivors – systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2879–88. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hamashima C. Long-Term quality of life of postoperative rectal cancer patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17:571–6. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramsey SD, Berry K, Moinpour C, et al. Quality of life in long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1228–34. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sapp AL, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, et al. Social networks and quality of life among female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer 2003;98:1749–58. 10.1002/cncr.11717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Health-Related quality of life in female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Oncologist 2003;8:342–9. 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim SP, Knight SJ, Tomori C, et al. Health literacy and shared decision making for prostate cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Cancer Invest 2001;19:684–91. 10.1081/CNV-100106143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Protheroe J, Wolf MS, Lee A. Health literacy and health outcomes. Health Literacy in Context: International Perspectives, 2010: 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aaby A, Friis K, Christensen B, et al. Health literacy is associated with health behaviour and self-reported health: a large population-based study in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24:1880–8. 10.1177/2047487317729538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.