Abstract

Purpose

The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) has collected cycle‐based assisted reproductive technology (ART) data in an online registry since 2007. Herein, we present the characteristics and treatment outcomes of ART cycles registered during 2017.

Methods

We collected cycle‐specific information for all ART cycles implemented at participating facilities and performed descriptive analysis.

Results

In total, 448,210 treatment cycles and 56,617 neonates (1 in 16.7 neonates born in Japan) were reported in 2017, increased from 2016; the number of initiated fresh cycles decreased for the first time ever. The mean patient age was 38.0 years (standard deviation 4.6). A total 110,641 of 245,205 egg retrieval cycles (45.1%) were freeze‐all cycles; fresh embryo transfer (ET) was performed in 55,720 cycles. A total 194,415 frozen‐thawed ET cycles were reported, resulting in 66,881 pregnancies and 47,807 neonates born. Single ET (SET) was performed in 81.8% of fresh transfers and 83.4% of frozen cycles, with singleton pregnancy/live birth rates of 97.5%/97.3% and 96.7%/96.6%, respectively.

Conclusions

Total ART cycles and subsequent live births increased continuously in 2017, whereas the number of initiated fresh cycles decreased. SET was performed in over 80% of cases, and ET shifted from using fresh embryos to frozen ones.

Keywords: ART registry, freeze‐all strategy, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the first baby in Japan conceived as a result of in vitro fertilization (IVF) was born in 1983, the number of assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles has dramatically increased each year. According to the latest report from the International Committee Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ICMART), Japan has been one of the largest users of ART worldwide in terms of annual number of treatment cycles performed.1

As it is essential to monitor the trend and situation of ART treatments implemented in the country, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) began an ART registry system in 1986 and launched an online registration system in 2007. Since then, cycle‐specific information for all ART treatment cycles performed in ART facilities has been collected. The aim of the present report was to describe the characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered ART cycles during 2017 in comparison with previous year.2

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Since 2007, the JSOG has requested all participating ART clinics and hospitals to register cycle‐specific information for all ART treatment cycles. The information includes patient characteristics, information on ART treatment, and pregnancy and obstetric outcomes. Detailed information collected in the registry has been reported previously.3 For ART cycles performed between January 1 and December 31, 2017, the JSOG requested registration of the information via an online registry system by the end of November 2018.

Using the registry data for 2017, we performed a descriptive analysis to investigate the characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered cycles. The number of registered cycles for the initiation of treatment, egg retrievals, fresh embryo transfer (ET) cycles, frozen‐thawed embryo transfer (FET) cycles, freeze‐all embryos/oocytes cycles, pregnancies, and neonates were compared with those in previous years. The characteristics of registered cycles and treatment outcomes were described for fresh ET and FET cycles. Treatment outcomes included pregnancy, miscarriage and live birth rates, multiple pregnancies, pregnancy outcomes for ectopic pregnancy, intrauterine pregnancy coexisting with an ectopic pregnancy, artificial abortion, stillbirth, and fetal reduction. Furthermore, the treatment outcomes of pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage, and multiple pregnancy rates were analyzed according to patient age. We also described treatment outcomes for cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes based on medical indications.

3. RESULTS

In Japan, there were 607 registered ART facilities in 2017, of which 606 participated in the ART registration system. A total 586 facilities actually implemented ART treatment in 2017; 19 registered facilities did not implement ART cycles. Trends in the number of registered cycles, egg retrievals, pregnancies, and neonates born as a result of IVF, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and FET cycles from 1985 to 2017 are shown in Table 1. In 2017, 448,210 cycles were registered, and 56,617 neonates were recorded, accounting for 1 in 16.7 neonates born in Japan (the total number of neonates born in Japan was 946,065 in 2017). The total number of registered cycles and neonates born as a result of ART demonstrated an increasing trend from 1985 to 2017. In 2017, for the first time ever, the number of registered cycles for fresh IVF and ICSI decreased from the previous year; registered IVF and ICSI cycles decreased by 3.2% and 2.2%, respectively, from the previous year. The number of FET cycles increased continuously; the number in 2017 was 198,985 (a 3.7% increase from 2016), resulting in 67,255 pregnancies and 48,060 neonates in 2017. Among registered fresh cycles, 63.3% were ICSI. In terms of FET cycles, 188,388 FETs were performed, resulting in 62,749 pregnancies and 44,678 neonates born in 2016.

Table 1.

Trends in the number of registered initiated cycles, egg retrievals, pregnancies, and neonates according to IVF, ICSI, and frozen‐thawed ET cycles in Japan, 1985‐2017

| Year | Fresh cycles | FET cyclesc | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVFa | ICSIb | |||||||||||||||

| No. of registered initiated cycles | No. of egg retrieval | No. of freeze‐all cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | No. of registered initiated cycles | No. of egg retrieval | No. of freeze‐all cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | No. of registered initiated cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | |

| 1985 | 1,195 | 1,195 | 862 | 64 | 27 | |||||||||||

| 1986 | 752 | 752 | 556 | 56 | 16 | |||||||||||

| 1987 | 1,503 | 1,503 | 1,070 | 135 | 54 | |||||||||||

| 1988 | 1,702 | 1,702 | 1,665 | 257 | 114 | |||||||||||

| 1989 | 4,218 | 3,890 | 2,968 | 580 | 446 | 184 | 92 | 7 | 3 | |||||||

| 1990 | 7,405 | 6,892 | 5,361 | 1,178 | 1,031 | 160 | 153 | 17 | 17 | |||||||

| 1991 | 11,177 | 10,581 | 8,473 | 2,015 | 1,661 | 369 | 352 | 57 | 39 | |||||||

| 1992 | 17,404 | 16,381 | 12,250 | 2,702 | 2,525 | 963 | 936 | 524 | 42 | 35 | 553 | 530 | 79 | 66 | ||

| 1993 | 21,287 | 20,345 | 15,565 | 3,730 | 3,334 | 2,608 | 2,447 | 1,271 | 176 | 149 | 681 | 597 | 86 | 71 | ||

| 1994 | 25,157 | 24,033 | 18,690 | 4,069 | 3,734 | 5,510 | 5,339 | 4,114 | 759 | 698 | 1,303 | 1,112 | 179 | 144 | ||

| 1995 | 26,648 | 24,694 | 18,905 | 4,246 | 3,810 | 9,820 | 9,054 | 7,722 | 1,732 | 1,579 | 1,682 | 1,426 | 323 | 298 | ||

| 1996 | 27,338 | 26,385 | 21,492 | 4,818 | 4,436 | 13,438 | 13,044 | 11,269 | 2,799 | 2,588 | 2,900 | 2,676 | 449 | 386 | ||

| 1997 | 32,247 | 30,733 | 24,768 | 5,730 | 5,060 | 16,573 | 16,376 | 14,275 | 3,495 | 3,249 | 5,208 | 4,958 | 1,086 | 902 | ||

| 1998 | 34,929 | 33,670 | 27,436 | 6,255 | 5,851 | 18,657 | 18,266 | 15,505 | 3,952 | 3,701 | 8,132 | 7,643 | 1,748 | 1,567 | ||

| 1999 | 36,085 | 34,290 | 27,455 | 6,812 | 5,870 | 22,984 | 22,350 | 18,592 | 4,702 | 4,247 | 9,950 | 9,093 | 2,198 | 1,812 | ||

| 2000 | 31,334 | 29,907 | 24,447 | 6,328 | 5,447 | 26,712 | 25,794 | 21,067 | 5,240 | 4,582 | 11,653 | 10,719 | 2,660 | 2,245 | ||

| 2001 | 32,676 | 31,051 | 25,143 | 6,749 | 5,829 | 30,369 | 29,309 | 23,058 | 5,924 | 4,862 | 13,034 | 11,888 | 3,080 | 2,467 | ||

| 2002 | 34,953 | 33,849 | 26,854 | 7,767 | 6,443 | 34,824 | 33,823 | 25,866 | 6,775 | 5,486 | 15,887 | 14,759 | 4,094 | 3,299 | ||

| 2003 | 38,575 | 36,480 | 28,214 | 8,336 | 6,608 | 38,871 | 36,663 | 27,895 | 7,506 | 5,994 | 24,459 | 19,641 | 6,205 | 4,798 | ||

| 2004 | 41,619 | 39,656 | 29,090 | 8,542 | 6,709 | 44,698 | 43,628 | 29,946 | 7,768 | 5,921 | 30,287 | 24,422 | 7,606 | 5,538 | ||

| 2005 | 42,822 | 40,471 | 29,337 | 8,893 | 6,706 | 47,579 | 45,388 | 30,983 | 8,019 | 5,864 | 35,069 | 28,743 | 9,396 | 6,542 | ||

| 2006 | 44,778 | 42,248 | 29,440 | 8,509 | 6,256 | 52,539 | 49,854 | 32,509 | 7,904 | 5,401 | 42,171 | 35,804 | 11,798 | 7,930 | ||

| 2007 | 53,873 | 52,165 | 7,626 | 28,228 | 7,416 | 5,144 | 61,813 | 60,294 | 11,541 | 34,032 | 7,784 | 5,194 | 45,478 | 43,589 | 13,965 | 9,257 |

| 2008 | 59,148 | 57,217 | 10,139 | 29,124 | 6,897 | 4,664 | 71,350 | 69,864 | 15,390 | 34,425 | 7,017 | 4,615 | 60,115 | 57,846 | 18,597 | 12,425 |

| 2009 | 63,083 | 60,754 | 11,800 | 28,559 | 6,891 | 5,046 | 76,790 | 75,340 | 19,046 | 35,167 | 7,330 | 5,180 | 73,927 | 71,367 | 23,216 | 16,454 |

| 2010 | 67,714 | 64,966 | 13,843 | 27,905 | 6,556 | 4,657 | 90,677 | 88,822 | 24,379 | 37,172 | 7,699 | 5,277 | 83,770 | 81,300 | 27,382 | 19,011 |

| 2011 | 71,422 | 68,651 | 16,202 | 27,284 | 6,341 | 4,546 | 102,473 | 100,518 | 30,773 | 38,098 | 7,601 | 5,415 | 95,764 | 92,782 | 31,721 | 22,465 |

| 2012 | 82,108 | 79,434 | 20,627 | 29,693 | 6,703 | 4,740 | 125,229 | 122,962 | 41,943 | 40,829 | 7,947 | 5,498 | 119,089 | 116,176 | 39,106 | 27,715 |

| 2013 | 89,950 | 87,104 | 25,085 | 30,164 | 6,817 | 4,776 | 134,871 | 134,871 | 49,316 | 41,150 | 8,027 | 5,630 | 141,335 | 138,249 | 45,392 | 32,148 |

| 2014 | 92,269 | 89,397 | 27,624 | 30,414 | 6,970 | 5,025 | 144,247 | 141,888 | 55,851 | 41,437 | 8,122 | 5,702 | 157,229 | 153,977 | 51,458 | 36,595 |

| 2015 | 93,614 | 91,079 | 30,498 | 28,858 | 6,478 | 4,629 | 155,797 | 153,639 | 63,660 | 41,396 | 8,169 | 5,761 | 174,740 | 171,495 | 56,888 | 40,611 |

| 2016 | 94,566 | 92,185 | 34,188 | 26,182 | 5,903 | 4,266 | 161,262 | 159,214 | 70,387 | 38,315 | 7,324 | 5,166 | 191,962 | 188,338 | 62,749 | 44,678 |

| 2017 | 91,516 | 89,447 | 36,441 | 22,423 | 5,182 | 3,731 | 157,709 | 155,758 | 74,200 | 33,297 | 6,757 | 4,826 | 198,985 | 195,559 | 67,255 | 48,060 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; FET, frozen‐thawed embryo transfer; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

Including gamete intrafallopian transfer.

Including split‐ICSI cycles.

Including cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes.

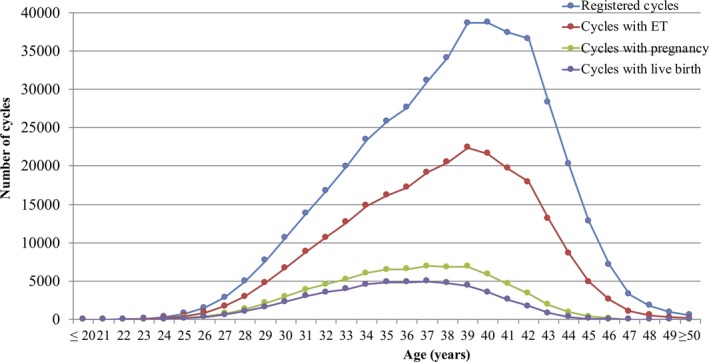

The distributions of patient age in registered cycles and different subgroups of cycles with ET, pregnancy, and live birth are shown in Figure 1. The mean patient age for registered cycles was 38.0 years (standard deviation [SD] =4.6); the mean age for pregnancy and live birth cycles was 36.0 years (SD = 4.1) and 35.5 years (SD = 4.0), respectively.

Figure 1.

Age distributions of all registered cycles, different subgroups of cycles for ET, pregnancy, and live birth in 2017. Adapted from the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology ART Databook 2017 (http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jsog-art/2017data_20191015.pdf). ET, embryo transfer

The characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered fresh cycles are shown in Table 2. There were 87,445 registered IVF cycles, 26,485 split‐ICSI cycles, 128,643 ICSI cycles using ejaculated sperm, 2,581 ICSI cycles using testicular sperm extraction (TESE), 25 gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) cycles, 537 cycles with oocyte freezing based on medical indications, and 3,509 other cycles. Of the 245,205 cycles with oocyte retrieval, 110,641 (45.1%) were freeze‐all cycles. The pregnancy rate per ET was 23.0% for IVF and 19.2% for ICSI using ejaculated sperm. Single ET was performed at a rate of 81.8%, with a pregnancy rate of 21.7%. Live birth rates per ET were 16.2% for IVF, 13.2% for ICSI using ejaculated sperm, and 10.2% for ICSI with TESE. The singleton pregnancy rate and live birth rate were 97.5% and 97.3%, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered fresh cycles in assisted reproductive technology in Japan, 2017

| Variables | IVF‐ET | Split | ICSI | GIFT | Frozen oocyte | Othersa | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculated sperm | TESE | |||||||

| No. of registered initiated cycles | 87,445 | 26,485 | 128,643 | 2,581 | 25 | 537 | 3,509 | 249,225 |

| No. of egg retrieval | 85,541 | 26,185 | 126,996 | 2,577 | 25 | 530 | 3,351 | 245,205 |

| No. of fresh ET cycles | 21,939 | 5,691 | 26,931 | 675 | 25 | 2 | 457 | 55,720 |

| No. of freeze‐all cycles | 34,930 | 17,320 | 55,585 | 1,295 | 0 | 457 | 1,054 | 110,641 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 5,047 | 1,475 | 5,174 | 108 | 7 | 0 | 128 | 11,939 |

| Pregnancy rate per ET | 23.0% | 25.9% | 19.2% | 16.0% | 28.0% | 0 | 28.0% | 21.4% |

| Pregnancy rate per egg retrieval | 5.9% | 5.6% | 4.1% | 4.2% | 28.0% | ‐ | 3.8% | 4.9% |

| Pregnancy rate per egg retrieval excluding freeze‐all cycles | 10.0% | 16.6% | 7.2% | 8.4% | 28.0% | ‐ | 5.6% | 8.9% |

| SET cycles | 18,428 | 4,913 | 21,502 | 412 | 3 | ‐ | 300 | 45,559 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 4,234 | 1,312 | 4,179 | 72 | 0 | ‐ | 86 | 9,883 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 84.0% | 86.3% | 79.8% | 61.0% | 12.0% | ‐ | 65.6% | 81.8% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 23.0% | 26.7% | 19.4% | 17.5% | 0.0% | ‐ | 28.7% | 21.7% |

| Miscarriages | 1,227 | 327 | 1,380 | 36 | 3 | ‐ | 31 | 3,004 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 24.3% | 22.2% | 26.7% | 33.3% | 42.9% | ‐ | 24.2% | 25.2% |

| Singleton pregnanciesb | 4,755 | 1,417 | 4,881 | 98 | 7 | ‐ | 121 | 11,279 |

| Multiple pregnanciesb | 114 | 35 | 136 | 4 | 0 | ‐ | 3 | 292 |

| Twin pregnanciesb | 113 | 33 | 134 | 3 | 0 | ‐ | 3 | 286 |

| Triplet pregnanciesb | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 6 |

| Quadruplet pregnanciesb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple pregnancy rateb | 2.3% | 2.4% | 2.7% | 3.9% | 0.0% | ‐ | 2.4% | 2.5% |

| Live births | 3,555 | 1,085 | 3,552 | 69 | 4 | ‐ | 90 | 8,355 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 16.2% | 19.1% | 13.2% | 10.2% | 16.0% | ‐ | 19.7% | 15.0% |

| Total number of neonates | 3,635 | 1,103 | 3,653 | 70 | 4 | ‐ | 92 | 8,557 |

| Singleton live births | 3,464 | 1,066 | 3,439 | 66 | 4 | ‐ | 88 | 8,127 |

| Twin live births | 84 | 17 | 107 | 2 | 0 | ‐ | 2 | 212 |

| Triplet live births | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 2 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 0 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | ||||||||

| Ectopic pregnancies | 58 | 12 | 63 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 3 | 136 |

| Intrauterine pregnancies coexisting with ectopic pregnancy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 2 |

| Artificial abortions | 18 | 5 | 25 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 48 |

| Stillbirths | 14 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 1 | 32 |

| Fetal reductions | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 2 |

| Unknown cycles for pregnancy outcomes | 102 | 32 | 111 | 2 | 0 | ‐ | 2 | 249 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; IVF‐ET, in vitro fertilization‐embryo transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; GIFT, gamete intrafallopian transfer; TESE, testicular sperm extraction; SET, single embryo transfer.

Others include zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT).

Singleton, twin, triplet, and quadruplet pregnancies were defined according to the number of gestational sacs in utero.

The characteristics and treatment outcomes of FET cycles are shown in Table 3. There were 197,593 registered cycles, among which FET was performed in 194,415 cycles leading to 66,881 pregnancies (pregnancy rate per FET = 34.4%). The miscarriage rate per pregnancy was 25.9%, resulting in a 23.9% live birth rate per ET. Single ET was performed at a rate of 83.5%, and the singleton pregnancy and live birth rates were 96.7% and 96.6%, respectively.

Table 3.

Characteristics and treatment outcomes of frozen‐thawed embryo transfer cycles in assisted reproductive technology, Japan, 2017

| Variables | FET | Othersa | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of registered initiated cycles | 197,593 | 1,199 | 198,792 |

| No. of FET | 194,415 | 1,053 | 195,468 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 66,881 | 353 | 67,234 |

| Pregnancy rate per FET | 34.4% | 33.5% | 34.4% |

| SET cycles | 162,343 | 746 | 163,089 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 57,167 | 241 | 57,408 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 83.5% | 70.8% | 83.4% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 35.2% | 32.3% | 35.2% |

| Miscarriages | 17,343 | 81 | 17,424 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 25.9% | 22.9% | 25.9% |

| Singleton pregnanciesb | 63,391 | 324 | 63,715 |

| Multiple pregnanciesb | 2,168 | 22 | 2,190 |

| Twin pregnanciesb | 2,126 | 22 | 2,148 |

| Triplet pregnanciesb | 42 | 0 | 42 |

| Quadruplet pregnanciesb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple pregnancy rateb | 3.3% | 6.4% | 3.3% |

| Live births | 46 396 | 228 | 46 624 |

| Live birth rate per FET | 23.9% | 21.7% | 23.9% |

| Total number of neonates | 47,807 | 235 | 48,042 |

| Singleton live births | 44,820 | 213 | 45,033 |

| Twin live births | 1,471 | 11 | 1,482 |

| Triplet live births | 15 | 0 | 15 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | |||

| Ectopic pregnancies | 354 | 2 | 356 |

| Intrauterine pregnancies coexisting with ectopic pregnancy | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Artificial abortions | 286 | 3 | 289 |

| Stillbirths | 180 | 1 | 181 |

| Fetal reduction | 15 | 0 | 15 |

| Unknown cycles for pregnancy outcomes | 1,901 | 33 | 1,934 |

Abbreviations: FET, frozen‐thawed embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer.

Including cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes.

Singleton, twin, triplet, and quadruplet pregnancies were defined according to the number of gestational sacs in utero.

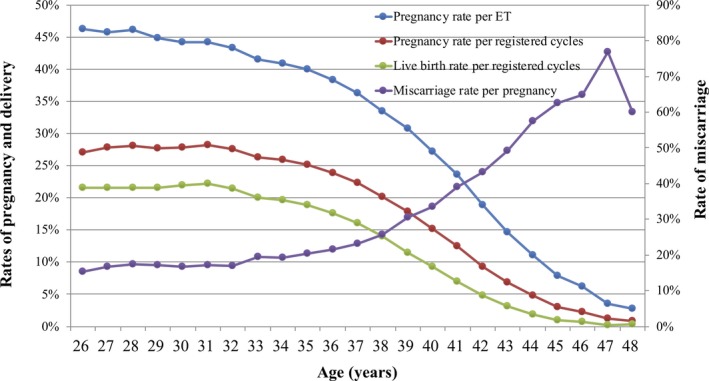

Treatment outcomes of registered cycles, including pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth, and multiple pregnancy rates, according to patient age, are shown in Table 4. Similarly, the distribution of pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates according to patient age are shown in Figure 2. The pregnancy rate per ET exceeded 40% up to 35 years of age; this rate gradually fell below 30% after age 39 years and below 10% after age 45 years. The miscarriage rate was below 20% under age 35 years but gradually increased to 33.6% and 49.3% for those aged 40 and 43 years, respectively. The live birth rate per registered cycle was around 20% up to 33 years of age and decreased to 9.3% and 3.1% at ages 40 and 43 years, respectively. Multiple pregnancy rates varied between 2% and 3% across most age groups.

Table 4.

Treatment outcomes of registered cycles, according to patient age in Japan, 2017

| Age (years) | No. of registered initiated cycles | No. of ET cycles | Pregnancy | Multiple pregnanciesa | Miscarriage | Live birth | Pregnancy rate per ET | Pregnancy rate per registered cycles | Live birth rate per registered cycles | Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | Multiple pregnancy ratea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 20s | 39 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 30.0% | 7.7% | 5.1% | 33.3% | 0.0% |

| 21 | 33 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 41.7% | 15.2% | 12.1% | 20.0% | 0.0% |

| 22 | 79 | 37 | 25 | 2 | 5 | 19 | 67.6% | 31.6% | 24.1% | 20.0% | 8.0% |

| 23 | 149 | 86 | 34 | 1 | 7 | 24 | 39.5% | 22.8% | 16.1% | 20.6% | 2.9% |

| 24 | 364 | 199 | 91 | 0 | 10 | 77 | 45.7% | 25.0% | 21.2% | 11.0% | 0.0% |

| 25 | 788 | 468 | 213 | 11 | 46 | 157 | 45.5% | 27.0% | 19.9% | 21.6% | 5.2% |

| 26 | 1,569 | 918 | 425 | 15 | 65 | 339 | 46.3% | 27.1% | 21.6% | 15.3% | 3.6% |

| 27 | 2,895 | 1,762 | 806 | 22 | 134 | 623 | 45.7% | 27.8% | 21.5% | 16.6% | 2.8% |

| 28 | 4,965 | 3,026 | 1,396 | 41 | 242 | 1,070 | 46.1% | 28.1% | 21.6% | 17.3% | 3.0% |

| 29 | 7,731 | 4,792 | 2,147 | 55 | 371 | 1,671 | 44.8% | 27.8% | 21.6% | 17.3% | 2.6% |

| 30 | 10,721 | 6,754 | 2,990 | 79 | 498 | 2,352 | 44.3% | 27.9% | 21.9% | 16.7% | 2.7% |

| 31 | 13,829 | 8,843 | 3,911 | 119 | 673 | 3,065 | 44.2% | 28.3% | 22.2% | 17.2% | 3.1% |

| 32 | 16,744 | 10,678 | 4,620 | 143 | 787 | 3,596 | 43.3% | 27.6% | 21.5% | 17.0% | 3.2% |

| 33 | 19,951 | 12,671 | 5,259 | 130 | 1019 | 3,988 | 41.5% | 26.4% | 20.0% | 19.4% | 2.5% |

| 34 | 23,392 | 14,806 | 6,055 | 175 | 1,172 | 4,611 | 40.9% | 25.9% | 19.7% | 19.4% | 2.9% |

| 35 | 25,809 | 16,210 | 6,492 | 247 | 1,321 | 4,869 | 40.0% | 25.2% | 18.9% | 20.3% | 3.9% |

| 36 | 27,594 | 17,184 | 6,583 | 249 | 1,424 | 4,867 | 38.3% | 23.9% | 17.6% | 21.6% | 3.9% |

| 37 | 31,095 | 19,156 | 6,940 | 255 | 1,612 | 5,000 | 36.2% | 22.3% | 16.1% | 23.2% | 3.8% |

| 38 | 34,081 | 20,484 | 6,867 | 224 | 1,762 | 4,778 | 33.5% | 20.1% | 14.0% | 25.7% | 3.3% |

| 39 | 38,618 | 22,400 | 6,894 | 238 | 2,111 | 4,440 | 30.8% | 17.9% | 11.5% | 30.6% | 3.5% |

| 40 | 38,698 | 21,604 | 5,872 | 184 | 1,973 | 3,603 | 27.2% | 15.2% | 9.3% | 33.6% | 3.2% |

| 41 | 37,365 | 19,672 | 4,645 | 146 | 1,819 | 2,626 | 23.6% | 12.4% | 7.0% | 39.2% | 3.2% |

| 42 | 36,600 | 17,946 | 3,394 | 82 | 1,466 | 1,763 | 18.9% | 9.3% | 4.8% | 43.2% | 2.5% |

| 43 | 28,253 | 13,138 | 1,932 | 43 | 952 | 881 | 14.7% | 6.8% | 3.1% | 49.3% | 2.3% |

| 44 | 20,255 | 8,667 | 965 | 17 | 555 | 371 | 11.1% | 4.8% | 1.8% | 57.5% | 1.8% |

| 45 | 12,836 | 4,956 | 393 | 4 | 246 | 130 | 7.9% | 3.1% | 1.0% | 62.6% | 1.0% |

| 46 | 7,147 | 2,634 | 165 | 0 | 107 | 54 | 6.3% | 2.3% | 0.8% | 64.8% | 0.0% |

| 47 | 3,275 | 1,093 | 39 | 0 | 30 | 8 | 3.6% | 1.2% | 0.2% | 76.9% | 0.0% |

| 48 | 1,799 | 556 | 15 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 2.7% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 60.0% | 7.1% |

| 49 | 973 | 317 | 14 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 4.4% | 1.4% | 0.3% | 71.4% | 0.0% |

| Over 50s | 563 | 200 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2.0% | 0.7% | 0.2% | 75.0% | 0.0% |

Abbreviation: ET, embryo transfer.

Multiple pregnancies were defined according to the number of gestational sacs in utero.

Figure 2.

Pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates, according to patient age, among all registered cycles in 2017. Adapted from the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology ART Databook 2017 (http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jsog-art/2017data_20191015.pdf). ET, embryo transfer

The treatment outcomes of cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes based on medical indications are shown in Table 5. There were a total of 91 cycles using frozen oocytes, among which 21 cycles resulted in pregnancy (pregnancy rate per FET = 23.1%). The miscarriage rate per pregnancy was 14.3%, resulting in a 19.8% live birth rate per ET.

Table 5.

Treatment outcomes of cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes based on medical indications in assisted reproductive technology, Japan, 2017

| Variables | Embryo transfer using frozen‐thawed oocyte |

|---|---|

| No. of registered cycles | 193 |

| No. of ET | 91 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 21 |

| Pregnancy rate per ET | 23.1% |

| SET cycles | 69 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 18 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 75.8% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 26.1% |

| Miscarriages | 3 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 14.3% |

| Singleton pregnanciesa | 20 |

| Multiple pregnanciesa | 1 |

| Twin pregnanciesa | 1 |

| Triplet pregnanciesa | 0 |

| Quadruplet pregnanciesa | 0 |

| Multiple pregnancy ratea | 4.8% |

| Live births | 18 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 19.8% |

| Total number of neonates | 18 |

| Singleton live births | 18 |

| Twin live births | 0 |

| Triplet live births | 0 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | |

| Ectopic pregnancies | 0 |

| Intrauterine pregnancies coexisting with ectopic pregnancy | 0 |

| Artificial abortions | 0 |

| Stillbirths | 0 |

| Fetal reduction | 0 |

| Unknown cycles for pregnancy outcomes | 0 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer.

Singleton, twin, triplet, and quadruplet pregnancies were defined according to the number of gestational sacs in utero.

4. DISCUSSION

Using the current Japanese ART registry system, we demonstrated that there were a total 448,210 registered ART cycles and 56,617 resultant live births, accounting for 1 in 16.7 neonates born in Japan during 2017, the most since the registry began. However, in 2017, the total number of initiated fresh cycles (both IVF and ICSI) decreased from the previous year for the first time. Freeze‐all cycles predominated, accounting for nearly 45% of total initiated cycles, resulting in frozen cycles accounting for most embryo transfers. The single ET rate was 81.8% for fresh transfers and 83.4% for frozen cycles, which also showed an increasing trend since 2007, reaching a singleton live birth rate of nearly 97% in total. These results represent the latest clinical practice of ART in Japan.

The characteristic that more than 45% of fresh cycles were freeze‐all is unique in Japan. Freeze‐all is beneficial for avoiding complications related to ovarian stimulation, such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), especially in high‐risk patients such as those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or high ovarian reserve.4 However, it remains under discussion whether the freeze‐all strategy is beneficial for the entire IVF population. A recently published meta‐analysis including 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 5,379 patients reported that freeze‐all and subsequent elective FET demonstrated significantly higher live birth rates than those with fresh ET (risk ratio [RR] =1.12, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01 to 1.24) in the entire population.5 Interestingly, neither the live birth rate (RR = 1.03, 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.17) in the subgroup of normo‐responders nor the cumulative live birth rate in the entire population (RR = 1.04, 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.11) was significantly different between groups. However, a more recent multicenter RCT investigating the effect of blastocyst ET after freeze‐all or fresh ET cycles among 825 ovulatory women from China demonstrated that a freeze‐all strategy with subsequent elective FET achieved a significantly higher live birth rate than did fresh blastocyst ET (RR = 1.26, 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.41).6 Thus, evidence for the use of a freeze‐all strategy in the entire IVF population remains limited.

FET might increase specific complications during pregnancy. Previous analysis using the Japanese ART registry has demonstrated that FET is associated with significantly higher risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and placenta accreta than fresh ET.7 In particular, higher risk of HDP in FET is noted in several RCTs.4, 6 Recently, it was reported that methods of endometrium preparation, especially hormone replacement cycles for FET, might be associated with these complications.8 Therefore, caution should be exerted with respect to the risks of specific pregnancy complications, although frozen ET is reported to be beneficial in avoiding OHSS and reducing the risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery, as compared with fresh cycles.9

ICSI cycles accounted for 63% of registered fresh cycles in 2017. An increasing trend in ICSI use is seen worldwide. The latest report from ICMART indicates that ICSI was used at a rate of 66.5% in 2011 among 65 countries and 2,560 ART clinics.1 That report also highlighted that large disparities exist for ICSI; the ICSI rate varies from 97% in Middle Eastern countries to 55% in Asia, 69% in Europe, and 73% in North America. Importantly, despite its increased use, there is no rigorous evidence that ICSI improves reproductive outcomes, especially for non‐male factor infertility such as unexplained infertility,10 low ovarian reserve, 11 or advanced maternal age.12 Based on this insufficient evidence, practice committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology have concluded that routine use of ICSI in patients with non‐male factor infertility is not recommended.13

The strength of the Japanese ART registry is its mandatory reporting system with a high compliance rate, in cooperation with the government subsidy system. Using this system, nearly all participating ART facilities (606 of 607 facilities) have registered cycle‐specific information.

Nevertheless, several limitations exist in the registry. First, the registry includes only cycle‐specific information; it is very difficult to identify cycles in the same patient using the registry. Under current Japanese ART practice, in which nearly half of initiated cycles are freeze‐all, current indicators such as pregnancy and live birth rate per aspiration cycle would be markedly underestimated. In fact, the abovementioned report from ICMART described that the delivery rate per oocyte aspiration in Japan was the lowest among 65 countries, which could mislead public opinion regarding the quality of treatment as ET was not performed in most included fresh cycles.1 It has recently been suggested that the cumulative live birth rate per oocyte aspiration is more suitable when reporting the success rate of IVF outcomes.14, 15 Yet, the appropriate definitions to be used in calculating the cumulative live birth rate are under discussion. The format of the Japanese ART registry may need to be changed, to report indicators for comparability.

Second, the Japanese ART registry includes unfertilized oocyte freezing cycles only for medically indicated cases, such as fertility preservation in cancer patients; the registry does not include cycles with non‐medical indications. Because no other regulatory measure in reproductive medicine that includes oocyte freezing is enforced in Japan, there is no information available regarding the practices outside this registry.

In conclusion, our analysis of the ART registry during 2017 demonstrated that the total number of ART cycles increased whereas the number of initiated fresh cycles decreased for the first time ever. SET was performed at a rate of more than 80%, resulting in a 97% singleton live birth rate. Although an increasing trend for frozen ET and freeze‐all cycles is characteristic in Japan, further investigation is required to evaluate the effect of the freeze‐all strategy and frozen ET on cumulative live births, and particularly with respect to both maternal and neonatal safety issues. These data represent the latest clinical practices of ART in Japan. Further improvement in the ART registration system in Japan is important.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this study.

HUMAN RIGHTS STATEMENT AND INFORMED CONSENT

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant committees on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included the study.

ANIMAL RIGHTS

This report does not contain any studies performed by any of the authors that included animal participants.

APPROVAL BY ETHICS COMMITTEE

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the registered facilities for their cooperation in providing their responses. We would also like to encourage these facilities to continue promoting use of the online registry system and assisting us with our research. This study was supported by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants. We thank Analisa Avila, ELS, of Edanz Group (http://www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: A summary report for 2017 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2020;19:3–12. 10.1002/rmb2.12307

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Chambers GM, et al. International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2011. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(6):1067‐1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: A summary report for 2016 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2019;18(1):7‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Irahara M, Kuwahara A, Iwasa T, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report of 1992–2014 by the Ethics Committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16(2):126‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen Z‐J, Shi Y, Sun Y, et al. Fresh versus frozen embryos for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):523‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roque M, Haahr T, Geber S, Esteves SC, Humaidan P. Fresh versus elective frozen embryo transfer in IVF/ICSI cycles: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of reproductive outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25(1):2‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wei D, Liu J‐Y, Sun Y, et al. Frozen versus fresh single blastocyst transfer in ovulatory women: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10178):1310‐1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ishihara O, Araki R, Kuwahara A, Itakura A, Saito H, Adamson GD. Impact of frozen‐thawed single‐blastocyst transfer on maternal and neonatal outcome: an analysis of 277,042 single‐embryo transfer cycles from 2008 to 2010 in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(1):128‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saito K, Kuwahara A, Ishikawa T, et al. Endometrial preparation methods for frozen‐thawed embryo transfer are associated with altered risks of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placenta accreta, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(8):1567‐1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sha T, Yin X, Cheng W, Massey IY. Pregnancy‐related complications and perinatal outcomes resulting from transfer of cryopreserved versus fresh embryos in vitro fertilization: a meta‐analysis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(2): 330–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Check JH, Yuan W, Garberi‐Levito MC, Swenson K, McMonagle K. Effect of method of oocyte fertilization on fertilization, pregnancy and implantation rates in women with unexplained infertility. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(3):203‐205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ou YC, Lan KC, Huang FJ, Kung FT, Lan TH, Chang SY. Comparison of in vitro fertilization versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection in extremely low oocyte retrieval cycles. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):96‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tannus S, Son WY, Gilman A, Younes G, Shavit T, Dahan MH. The role of intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non‐male factor infertility in advanced maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(1):119‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive M, Society for Assisted Reproductive T . Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) for non‐male factor infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6):1395‐1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maheshwari A, McLernon D, Bhattacharya S. Cumulative live birth rate: time for a consensus? Hum Reprod. 2015;30(12):2703‐2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS. Cumulative live‐birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):236‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]