Abstract

Lead-free double perovskites have been considered as a potential environmentally friendly photovoltaic material for substituting the hybrid lead halide perovskites due to their high stability and nontoxicity. Here, lead-free double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 films are initially fabricated by single-source evaporation deposition under high vacuum condition. X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy characterization show that the high crystallinity, flat, and pinhole-free double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 films were obtained after post-annealing at 300 °C for 15 min. By changing the annealing temperature, annealing time, and film thickness, perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells with planar heterojunction structure of FTO/TiO2/Cs2AgBiBr6/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag achieve an encouraging power conversion efficiency of 0.70%. Our preliminary work opens a feasible approach for preparing high-quality double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 films wielding considerable potential for photovoltaic application.

Keywords: lead-free, perovskite solar cell, thin film, single-source vapor deposition

1. Introduction

Organic–inorganic hybrid lead halide perovskite material family for photovoltaic application has attracted considerable attention in the past few years due to its excellent optoelectronic properties [1,2]. This material has also been rapidly developed with a power conversion efficiency (PCE) exceeding 24% [3]. However, two challenging problems still need to be solved, namely, lead toxicity and long-term stability issues, for the commercial application of perovskite solar cells (PSCs) [4,5]. Therefore, to date, many researchers have given considerable attention to the development of inorganic and/or environmentally friendly Pb-free perovskite materials to obtain highly stable nontoxic PSC devices [6,7]. A commonly applied approach toward Pb-free perovskites is to replace heavy metal Pb2+ ions with the divalent metal Sn2+ ions. However, the stability of tin-based PSC device under ambient environment is not ideal, because the divalent Sn2+ ion is easily oxidized into tetravalent Sn4+ ion [8]. Alternatively, nontoxic bismuth (Bi) based inorganic perovskites have been applied in solar cell devices as light absorber layers due to their high stability. However, Bi-based perovskites (A+1B2+X−13) cannot form three-dimensional (3D) structure of traditional perovskites, but only have zero-dimensional (0D) or two-dimensional (2D) structure of A+13B3+2X−19, which commonly results in unfavorable optoelectronic properties, such as high exciton binding energy, low carrier mobility, short carrier diffusion length, and high trap-state density [9,10]. Recently, the novel inorganic double perovskite material (Cs2AgBiX6 (X = Cl, Br)) has drawn research attention due to their high stability and nontoxicity, and their single crystal with highly symmetric cubic structure has been synthesized in succession [11,12,13]. This newly discovered double perovskite, especially the Cs2AgBiBr6, has been theoretically and experimentally tested to be a potential candidate for photovoltaic application due to their advantages of long carrier recombination lifetime, low toxicity, and high stability [5,14,15,16,17]. Moreover, in recent years, some articles regarding the perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells have been reported [18,19,20,21,22], and its highest PCE achieved is close to 2.51% [23]. The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells is much lower than that of conventional perovskite devices, mainly because double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 is the semiconductor material with an indirect bandgap and narrow optical absorption wavelength range (its bandgap is ~2 eV). As a result, the current density of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells is very low and the perovskite efficiency is not high. Further improvement can be obtained by the bandgap engineering of double perovskite. Additionally, its bandgap can be tunable from 0.5 eV to 2.7 eV [24]. For example, element Tl (I) can be added into Cs2AgBiBr6 to form Cs2(Ag1−aBi1−b)TlxBr6 (x = 0.075), with a direct bandgap of 1.57 eV [25]. Two methods are available for preparing double perovskite films, namely, solution-processing and vapor deposition. Greul et al. used a simple one-step spin-coating method to prepare the mesostructure Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells. The absorber layer was fabricated by directly spin-coating the precursor of BiBr3, AgBr, and CsBr on the porous TiO2, but the surface morphology of Cs2AgBiBr6 films appeared to be poor, with high roughness and defect density [21]. Especially, perovskite films with pinholes may cause the direct contact between electron and hole transport layers, which result in photogenerated carrier recombination loss. This is mainly because the perovskite films that are prepared by solution-processing are very sensitive to conditions of film forming, such as annealing temperature [26], solution concentration [27], precursor composition [28], and solvent selection [29]. Gao et al. and Wu et al. obtained flat Cs2AgBiBr6 films by anti-solvent and low-pressure assisted methods, respectively, but the low solubility (less than 0.6 mol/L) of double perovskite precursors in common solvents limits the preparation of high-quality films, as well as their commercial applications. In addition, Wang et al. prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells by the sequential vapor deposition. The fabrication is complicated for sequentially evaporating AgBr, BiBr3 and CsBr powder under high vacuum and determining their suitable composition ratio, and the composition ratios of the prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films greatly deviated from the ideal stoichiometry, which is not conducive to the preparation of high-efficiency solar cells. Single-source vapor deposition is an alternative method for the preparation of perovskite films [30,31]. The materials to be deposited is placed on a metal heater, and then rapidly evaporated onto the substrates by adjusting the heating current. Through this simple method, the Cs2AgBiBr6 films have the advantages of good smoothness, high uniformity, and high crystallinity. Inspired by this, we fabricated Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells by single-source vapor deposition.

In this work, we successfully fabricated double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 film by single-source vapor deposition. The annealing effects on the crystallinity and optical properties of Cs2AgBiBr6 films were systematically investigated. We found that the Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at 300 °C for 15 min had better properties with high crystallinity, good uniformity, and free pinholes. Planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells based on this film were prepared. By adjusting the annealing conditions and film thickness, the Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell devices show an optimized PCE of approximately 0.70%.

2. Materials and Methods

All of the preparation chemical materials were used without any further purification. All of the fabrication processes were operated under ambient conditions, except the preparation of the hole transporting layer (HTL) and the post-annealing, which were conducted in a glove box filled with nitrogen.

2.1. Cs2AgBiBr6 Crystal and Powder Preparation

The double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 crystals were prepared via the modified crystallization method [5]. The detailed processes are as follows: 426 mg CsBr (2.00 mmol, 99.5%, MACKLIN, Shanghai, China), 188 mg AgBr (1.00 mmol, 99.9%, MACKLIN, Shanghai, China), and 449 mg BiBr3 (1.00 mmol, 99%, Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA) powder were sequentially dissolved in 12 mL of hydrobromic acid (HBr, ACS, 48%, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) solution in a transparent glass bottle. Subsequently, the glass bottle was tightly sealed and placed into the petri dish filled with silicone oil. The silicone oil was gradually heated to 110 °C and then held for approximately 3 h to dissolve the raw material entirely and obtain a clear precursor solution. Subsequently, the solution was smoothly cooled down to 58 °C at a rate of 3 °C/h. Thereafter, minute Cs2AgBiBr6 crystals can be observed. The solution was kept at 58 °C for another 9 h to further promote crystal growth. Subsequently, the solution was cooled down to 35 °C at 1 °C/h. Finally, the well-grown Cs2AgBiBr6 crystals were collected by filtrating and were then washed by isopropyl alcohol (AR, ≥99.5%, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) three times. After drying in the oven, the prepared crystals could be ground to powder for use.

2.2. Device Fabrication

Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glasses (2.0 × 2.0 cm2, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) were ultrasonically sequentially then cleaned with industrial detergent, deionized water, and ethanol for 30 min. After treatment with ultraviolet (UV) ozone cleaning system for 15 min, the titanium dioxide (TiO2) was fabricated by spin-coating TiO2 precursor solution [32] at 3000 rpm for 30 s and then annealed at 450 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the Cs2AgBiBr6 films were deposited onto the TiO2-coated substrates by single-source vapor deposition. First, Cs2AgBiBr6 powder was loaded into the tungsten boat, and the cleaned FTO substrates were then fixed onto a rotatable holder above the evaporation source. The distance between the substrates and the evaporation source is approximately 20 cm. When the pressure in the vacuum chamber dropped down to 5.0 × 10−4 Pa, the evaporation source was smoothly heated to evaporate the perovskite powder by adjusting the heating current from 0 A to 120 A at a rate of 20 A/min. Meanwhile, the substrate holder was rotating at a rate of 20 rpm. The Cs2AgBiBr6 powder was completely evaporated in only a few minutes, and the Cs2AgBiBr6 films were then formed. The device performance of PSCs was optimized by varying the post-annealing temperatures (150 °C, 250 °C, 300 °C, and 350 °C), annealing times (5 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 65 min) and film thicknesses (167 nm, 238 nm, and 297 nm). Thereafter, the HTL was prepared by spin-coating 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis-(N,N-di-4-methoxyphenylamino)-9,9′-spirobi-fluorene (Spiro-OMeTAD, 99.7%, MACKLIN, Shanghai, China) solution on the perovskite film at 3000 rpm for 30 s. The preparation processes of the Spiro-OMeTAD solution are as follows. First, 145 mg Spiro-OMeTAD powder was dissolved in 2 mL of chlorobenzene (99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Second, 57 μL of 4-tert-butylpyridine (AR, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and 35 μL of bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonamide lithium salt (99.9%, MACKLIN, Shanghai, China) solution (520 mg/mL) in acetonitrile (super dehydrated, Wako, Tokyo, Japan) were sequentially added to the Spiro-OMeTAD solution. Third, the solution was filtered. Finally, approximately 80-nm-thick Ag thin film was deposited on the top of the device at a rate of 0.5 Å/s by the vacuum thermal evaporation method.

2.3. Characterization

The crystallinity of the samples was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Ultima IV, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) by using CuKα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were measured by SUPRA 55 Sapphire SEM (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with an accelerated voltage of 3 kV. UV–visible (UV–vis) absorption spectra were measured by a UV–vis–near-infrared spectrophotometer (Lambda 950, Perkin Elmer, Akron, OH, USA) with a wavelength range of 175–3300 nm and resolution of <0.05 nm. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the products were measured by a Raman spectrometer (inVia, Renishaw, Gloucestershire, England), with an excited wavelength of 532 nm (50 mW) and a spectral resolution of 1 cm−1. The film thicknesses of perovskite films were measured on the DEKTAKXT profilometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectra were recorded with the multimodal ultrafast spectroscopy system (SOLSTICS-1K, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) with a 35 femtosecond Ti: sapphire chirped pulse amplifier (Spectra-Physics Spitfire Pro 35) operating at a 1 kHz repetition rate and generating 35 fs pulse that was centered at approximately 800 nm. The valence band (VB) of the perovskite material in this work was performed by UV photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS). The spectrometer setup is equipped with a monochromatic He I source (21.2 eV) and a VG Scienta R4000 analyzer (Uppsala, Sweden). The current density–voltage (J–V) curves of the PSCs were measured by a Keithley 2400 (SolarIV-150A, Zolix, Beijing, China) under simulated AM 1.5 Solar Simulator (100 mW/cm2). The active area of the solar cell was approximately 0.1 cm2. The external quantum efficiency (EQE) was measured while using an EQE 200 Oriel integrated system (SCS1011, Zolix, Beijing, China) under 1.5 AM white light.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystalline Properties of Cs2AgBiBr6 Films

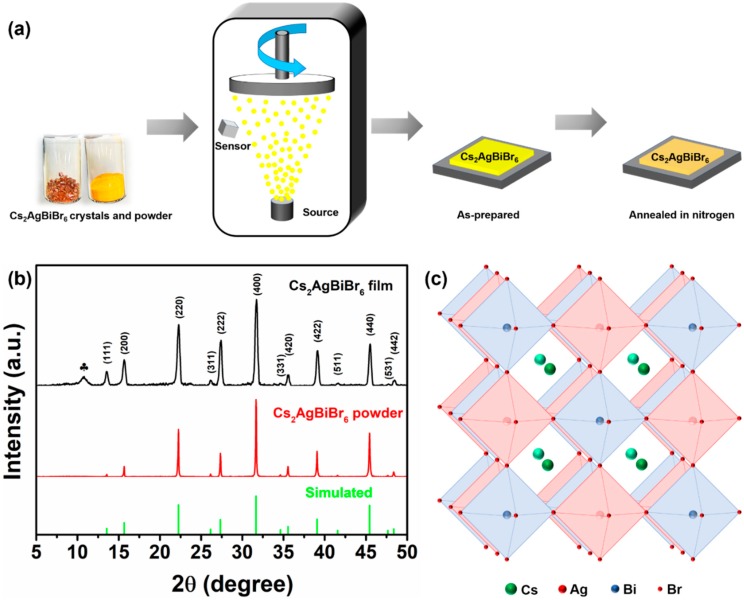

As shown in Figure 1a, the single-source vapor deposition method was used for preparing our Cs2AgBiBr6 films. High-quality Cs2AgBiBr6 single crystals were initially produced according to our modified method, and the detailed process is shown in Experimental Details (Supporting Information). Our prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 single crystals show an octahedral structure with bright surfaces and a size up to a millimeter (Figure S1) [5,18,20]. Our prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 powder could endure high heating temperature up to 430 °C without weight loss (Figure S2). The as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films are yellow in comparison with orange Cs2AgBiBr6 powder. The films turned into orange after being thermally annealed at high temperature.

Figure 1.

Schematic of Cs2AgBiBr6 film preparation (a). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 film and powder (b). Crystal structure of Cs2AgBiBr6 (c). The position of reflection labeled by club (♣) indicates the additional phase of BiOBr.

As shown in Figure 1b, the XRD patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 film and powder were in agreement with the simulated result. The film diffraction peaks located at 13.6°, 15.7°, 22.2°, 26.1°, 27.3°, 31.7°, 34.6°, 35.6°, 39.1°, 41.6°, 45.4°, 47.7°, and 48.4° could be indexed as the (111), (200), (220), (311), (222), (400), (331), (420), (422), (511), (440), (531), and (442) planes of Cs2AgBiBr6 perovskite, respectively [5,13]. This phenomenon indicates that our method synthesized the high-crystallinity Cs2AgBiBr6 films. Figure 1c shows the crystal structure of perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6. Moreover, the additional minor diffraction peak located at 10.82° represents the BiOBr side phase, which indicates that the perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 partially decomposed into BiBr3 during deposition and then hydrolyzed into BiOBr during post-annealing.

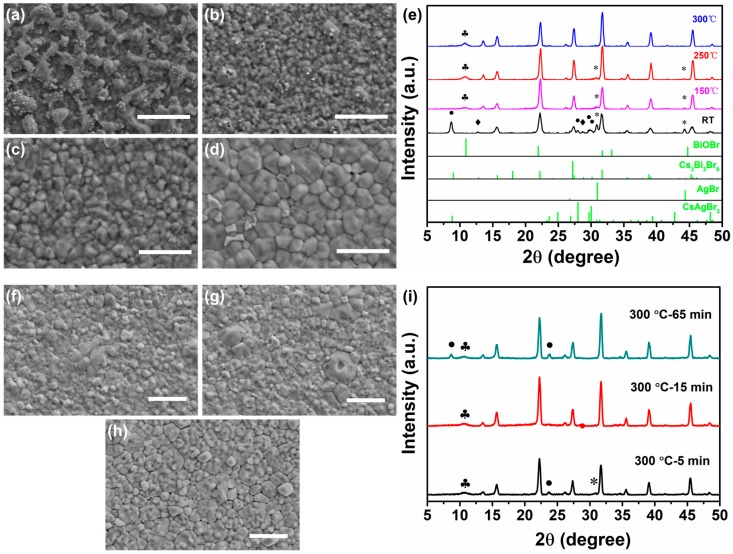

The samples were thermally annealed at different temperatures to investigate the effect of post-annealing on the surface morphology and crystalline of Cs2AgBiBr6 film. The as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films were respectively annealed at 150 °C, 250 °C and 300 °C for 30 min in the nitrogen-filled glove box. Figure 2a–d shows the SEM surface morphology of Cs2AgBiBr6 films with and without annealing. It can be observed that the as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 film is covered completely, but with many island masses. However, the Cs2AgBiBr6 films became remarkably uniform and smooth after thermally annealing. Besides, grain size gradually increased up to several hundreds of nanometers with the annealing temperature increasing from 150 °C to 300 °C, indicating higher crystalline Cs2AgBiBr6 films that were obtained by thermally annealing. Nevertheless, for the film annealed at 350 °C, the film coverage became very poor, as shown in Figure S3. It can be inferred that the Cs2AgBiBr6 film may partially decompose under much high annealing temperature (350 °C), which was confirmed by the following XRD results. The XRD patterns of the Cs2AgBiBr6 films with and without annealing are shown in Figure 2e. The as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films feature additional diffraction peaks at 8.70°, 12.76°, 28.02°, 28.74°, 29.72°, 30.10°, 30.86°, and 44.20°, which indicates the unexpected phases of CsAgBr2, Cs3Bi2Br9, and AgBr [15,21]. This XRD results imply that the double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 decomposed into CsAgBr2, Cs3Bi2Br9, and AgBr during the process of deposition. Notably, the side phases gradually decreased with the treatment of post annealing from 150 °C to 300 °C. Additionally, high-purity Cs2AgBiBr6 films without the additional phases of CsAgBr2, Cs3Bi2Br9 and AgBr were obtained under the annealing temperature of 300 °C. However, for the film annealed at 350 °C, it is obvious that we could see the diffraction peaks of side phases CsAgBr2 and Cs3Bi2Br9, being labeled by circle (•) and diamond (♦), respectively, in Figure S4. Their peak intensity is much stronger than that of Cs2AgBiBr6, suggesting that Cs2AgBiBr6 film would decompose into CsAgBr2 and Cs3Bi2Br9 when the annealing temperature was up to 350 °C. However, there is no decomposition in Cs2AgBiBr6 crystals in the range of room temperature to 350 °C, according to the literature that was reported by Gao et al. [20], indicating that high-quality Cs2AgBiBr6 crystals may feature higher thermal decomposition temperature than Cs2AgBiBr6 films. In addition, the club (♣) indicates the diffraction peaks from the side phase BiOBr, as discussed in Figure 1b. From the XRD patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 films, it is found that there are three major diffraction peaks of (220), (400), and (440) planes. Their corresponding peak intensity, as a function of annealing temperature, is displayed in Figure S5, respectively. We find that the intensity of the three major peaks increased after annealing and performed the most strongly between the annealing temperatures of 250 °C and 300 °C, which indicated that Cs2AgBiBr6 films with higher crystalline were obtained with post-annealing treatment. In order to further optimize the film quality, our as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films were also annealed at 300 °C for 5 min, 15 min, and 65 min, respectively. The SEM images show that the films from 5 min, 15 min, and 30 min are all dense and uniform, whereas Figure 2f–h show the films from 65 min have many defects, such as pinholes and cracks. The XRD patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at 300 °C for 5 min, 15 min and 65 min are displayed in Figure 2i. The diffraction peak intensity from the preferred orientations of (220), (400) and (440) planes as a function of annealing time was carried out in Figure S6. It could be observed that the peak intensity of (220), (400), and (440) planes increased with the annealing time increasing from 5 min to 30 min, whereas it decreased with more annealing time of 65 min. So suitable annealing time is beneficial to obtain the high crystalline Cs2AgBiBr6 films. Moreover, the diffraction peaks of Cs2AgBiBr6 films from 5 min, 30 min and 65 min, labeled with circle (•), asterisk (*), and club (♣), correspondingly indicate the additional phases of CsAgBr2, AgBr, and BiOBr, which suggests that the annealing time of 15 min can sufficiently obtain the desired Cs2AgBiBr6 films.

Figure 2.

SEM images and XRD patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at different temperatures for different time. (a–d) Cs2AgBiBr6 films were annealed at different temperatures for 30 min respectively. RT (ca. 25 °C) (a), 150 °C (b), 250 °C (c), and 300 °C (d). (e) XRD patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 films without and with annealing at 150, 250 and 300 °C. (f–h) Cs2AgBiBr6 films were annealed at 300 °C for different time. 5 min (f), 15 min (g), 65 min (h). (i) XRD patterns of Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at 300 °C for 5, 15 and 65 min, respectively. The positions of reflections labeled by circle (•), diamond (♦), asterisk (*), and club (♣) indicate the additional phases of CsAgBr2 (PDF#38-0850), Cs3Bi2Br9 (PDF#44-0714), AgBr (PDF#06-0438), and BiOBr (PDF#52-0084), respectively. The scale bars in the SEM images are all 1 μm.

3.2. Photophysical Properties and Energy Band Structure of Cs2AgBiBr6 Films

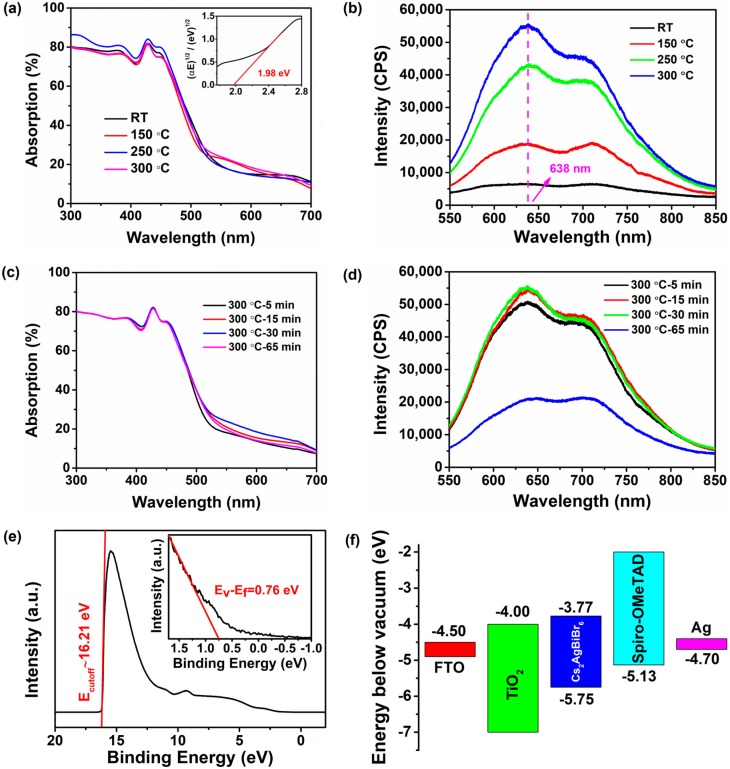

The UV–vis absorption and PL spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at different temperatures were also measured in order to further investigate the optical properties of Cs2AgBiBr6 films, as shown in Figure 3a,b. The as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films were annealed at 150 °C, 250 °C, and 300 °C for 30 min respectively in the nitrogen-filled glove box. It can be observed that all the absorption spectra feature three parts, namely, a smooth absorption of approximately 80% below 450 nm, a steep absorption in the wavelength region of 450–520 nm, and a weak absorption lower than 25% above 520 nm, which indicates that double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 film has high thermal stability even under 300 °C, whereas the typical perovskites decompose at 150 °C. In the literatures previously reported, there is commonly a sharp absorption peak located at ~450 nm that might arise from a direct bismuth s-p transition [33], whereas no such feature can be observed in our Cs2AgBiBr6 film. That probably attributes to our different methods for the preparation of perovskite thin films. The Tauc plot (see inset in Figure 3a), which was obtained from the absorption spectrum of Cs2AgBiBr6 film, determined an indirect band gap of approximately 1.98 eV, which is in agreement with the previously reported results [21]. From the PL spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 films with different annealing temperatures (Figure 3b), we found that only two thin films annealed at 250 °C and 300 °C feature a wide typical PL peak located at approximately 638 nm (1.94 eV) and the PL peak of the thin film annealed at 150 °C is not obvious, which indicated that the post-annealing process with more than annealing temperature of 250 °C is necessary for obtaining desired Cs2AgBiBr6 film. It is worth noting that the PL spectra of our Cs2AgBiBr6 films exhibit an additional peak at ~710 nm (~1.75 eV), which is similar to the situation in the previous literature [20]. The report pointed out that this additional peak originates from the photon-assisted indirect band transitions processes. However, no phonon-assisted processes with transitions at ~1.75 eV could be observed in our Tauc plot, which suggests that this additional peak might arise from the direct bandgap emission of Cs2AgBiBr6. Besides, the peak intensity became stronger with the annealing temperature increasing. For comparison, the PL spectrum of our synthesized Cs2AgBiBr6 crystal was also measured, as shown in Figure S7. The measured result matched well with that of Cs2AgBiBr6 film annealed at 300 °C, which suggests that high-homogeneity Cs2AgBiBr6 films were obtained with the treatment of annealing. The optical properties of Cs2AgBiBr6 films with different annealing time (5 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 65 min) were also studied (Figure 3c,d). It can be seen that the optical absorption with different annealing time is very similar to each other in the whole wavelength range (Figure 3c), as discussed above, although the Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at 300 °C for 65 min have many pinholes and cracks shown in the SEM image. As shown in Figure 3d, all of the PL spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at 300 °C with different annealing time possessed similar obvious PL peaks, except the thin film annealed at 300 °C for 65 min. Additionally, the PL peak intensity increased with the annealing time increasing from 5 min to 15 min, but it hardly changed when the annealing time was up to 30 min. The increased PL peak intensity indicates that non-radiative decay in our Cs2AgBiBr6 films is significantly suppressed and. as a result, the number of defects decrease by our annealing [34]. These results imply that too much annealing time under high temperature is not favorable for the preparation of high-quality Cs2AgBiBr6 film and, in our experiment, the annealing time of 30 min is suitable for obtaining the desire thin film.

Figure 3.

(a,b) UV-vis and photoluminescence (PL) spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 films with and without annealing. As-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films were annealed at 150 °C, 250 °C and 300 °C for 30 min respectively. Inset in (a) is the Tuat plot obtained from the optical absorption spectrum. (c,d) UV-vis and PL spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 films annealed at 300 °C for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 65 min respectively. (e) UPS spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 film annealed at 300 °C for 15 min. (f) Energy band diagram of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell with the planar structure of FTO/compact TiO2/Cs2AgBiBr6/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag.

UPS was used to calculate the energy band structure of the annealed Cs2AgBiBr6 film as shown in Figure 3e,f. The work function (Ef) can be calculated by the equation Ef = 21.2 eV (He I) − Ecutoff, where Ecutoff is 16.21 eV, as presented in Figure 3e, and the resulting value of EF is 4.99 eV. The linear extrapolation in the low binding-energy region (see inset in Figure 3e) indicates the value of (EV − EF), leading to an EV of 5.75 eV. As a result, the conduction band (EC) energy of Cs2AgBiBr6 film can be estimated by the value of (EV − Eg) and the relative EC value is 3.77 eV. The EF energy level is near the top of VB (EV), which suggests that the prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 film is probably a p-type semiconductor. We carried out the energy band diagram of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell with the planar structure of FTO/TiO2/Cs2AgBiBr6/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag, based on the calculating results of energy band structure of Cs2AgBiBr6 film, as shown in Figure 3f. According to the energy band theory, the photogenerated electrons and holes in the Cs2AgBiBr6 film can separately transport through the hole and electron blocking layers (TiO2 and Spiro-OMeTAD) to the electrodes (FTO and Ag), which would meet the requirement for the preparation of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell.

3.3. Photogenerated Carrier Lifetime of Cs2AgBiBr6 Films

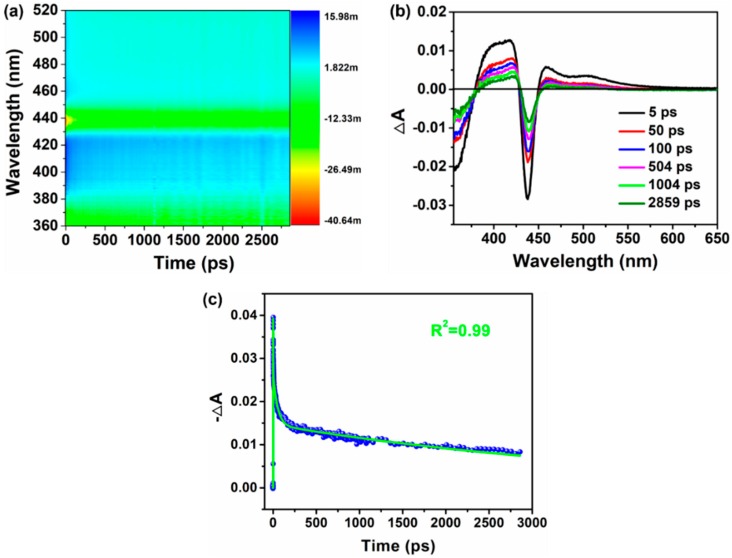

The femtosecond TA spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 film were carried out to estimate the lifetime of photoinduced charge carriers of Cs2AgBiBr6 film, as shown in Figure 4. A GSB at 439 nm can be observed for perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 film (Figure 4a), which originates from the state-filling effect [35,36]. Two broad photoinduced absorption bands correspondingly centered at 458 nm and 504 nm can be seen at early times and then rapidly turn into a strong bleaching at a long time (Figure 4b). As previously reported [37,38], this characteristic is a typical feature assigned to exciton–exciton interaction. Three components can fit the GSB decay probed at 439 nm, namely, a short-lived lifetime of~1.3 ps, a middle-lived lifetime of ~50 ps, and a long-lived lifetime of ~4.3 ns (Figure 4c). According to the literature [39], the short- and middle-lived components correspond to the subband gap trapping processes, whereas the long-lived component can be attributed to the carrier recombination processes. The much lower carrier recombination lifetime of the Cs2AgBiBr6 films than that reported by Yang et al. [23] may be ascribed to the higher defect state density that results from the additional phase of BiOBr in our films. Moreover, in the literature by Slavney et al. [5], the Cs2AgBiBr6 crystals and powder both show a long carrier recombination lifetime of ~660 ns, which is much longer than those from Cs2AgBiBr6 films, indicating that Cs2AgBiBr6 films are likely to have more defects than crystals or powder.

Figure 4.

Femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectra of Cs2AgBiBr6 film with an excited energy of 350 nm. (a) Pseudocolor TA plot. (b) TA spectra at indicated delay time from 5 ps to 2859 ps. (c) Ground-state bleach (GSB) decay dynamic probed at 439 nm. The as-prepared Cs2AgBiBr6 films were annealed at 300 °C for 15 min.

3.4. Photovoltaic Performance

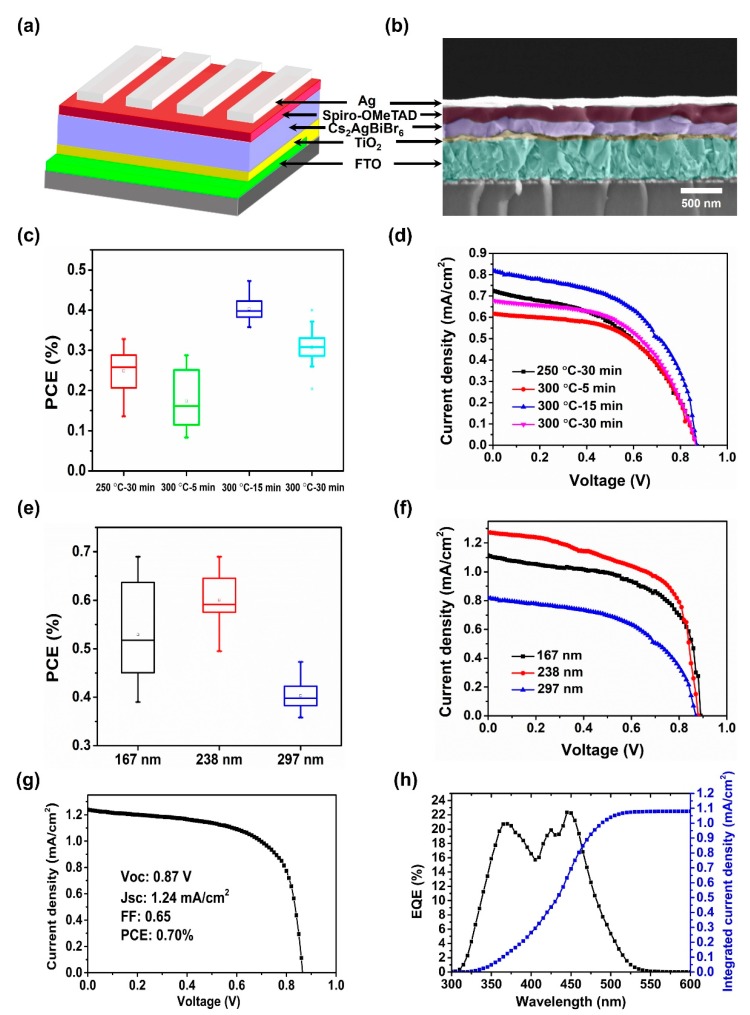

We fabricated the solar cells based on the planar heterojunction structure of FTO/TiO2/Cs2AgBiBr6/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag to test the device performance of Cs2AgBiBr6 film. The Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell structure and the cross-section SEM image of solar cell device are shown in Figure 5a,b, respectively. The incorporated Cs2AgBiBr6 film was annealed at 300 °C for 15 min and its measured thickness is approximately 167 nm. It can be observed that the Cs2AgBiBr6 grains are comparable with the film thickness, which indicates that most of the photogenerated charges can reach the electron and hole transport layer (TiO2 and Spiro-OMeTAD) without encountering grain boundaries, which leads to the reduction of photogenerated carrier recombination loss. This condition is beneficial in the preparation of efficient PSCs. Figure 5c shows the PCEs of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells with different annealing temperatures and time and the corresponding device parameters were summarized in Table S1. A PCE maximum was achieved from the solar cell device assembled with Cs2AgBiBr6 film annealed at 300 °C for 15 min, which is mainly attributed to the increased Jsc (Figure 5d and Figure S8), caused by the higher crystalline and larger grains of Cs2AgBiBr6 films after annealing. The improved crystallization and large grains are favorable in reducing the grain boundaries and trapping states, which leads to less recombination loss in Cs2AgBiBr6 films and longer lifetime of photogenerated carriers. To further optimize the device performance, we also fabricated series of solar cells assembled with different Cs2AgBiBr6 film thicknesses. Figure 5e shows the device performance of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells as a function of film thickness (167 nm, 238 nm, and 297 nm) and the solar cell parameters are summarized in Table S2. The best PCEs were achieved from a thicker thin film of 238 nm with increased Jsc (Figure 5f and Figure S9). However, the devices that were assembled with extremely thick perovskite films exhibited very low Jsc, which may suffer from the additional phase of BiOBr in our films. According to the literature by Greul et al., solar cells with phase-pure double perovskite films have much higher Jsc than those with side phases of Cs3Bi2Br9 and AgBr. Additionally, the short carrier recombination lifetime in our Cs2AgBiBr6 films is another reason why our solar cell efficiency is very low. As discussed in Figure 4, our Cs2AgBiBr6 films has much lower carrier recombination lifetime of ~4.3 ns than those (220 ns and 117 ns) from Greul’s and Wang’s. In addition, our prepared devices show a wide deviation of PCE in the case of 167 nm film when compared to 238 nm and 297 nm cases, which originates from the pinholes in perovskite films (Figure S10). The achieved PCE of the champion device is approximately 0.70% with Voc of 0.87 V, Jsc of 1.24 mA/cm2, and FF of 0.65 through the optimized preparation conditions (Figure 5g). The J-V curves of our Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cells show a hysteresis under forward and backward scanning direction (Figure S11) that can be attributed to the low activation barrier of halide anions during migration in perovskite devices [40]. The integrated current of 1.08 mA/cm2 confirmed the tested current density (Jsc) of solar cell (Figure 5h).

Figure 5.

(a) Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell structure, FTO/compact TiO2/Cs2AgBiBr6/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag. (b) Cross-section SEM image of solar cell device. (c) Device performance as a function of annealing temperature and time. (d) J–V curves of solar cell devices with different annealing temperatures and time. (e) Device performance as a function of film thickness. (f) J–V curves of solar cell devices with different thicknesses of absorber layer. Cs2AgBiBr6 films were annealed at 300 °C for 15 min. (g,h) J–V curve, and the corresponding EQE spectrum (black) and its integrated current density (blue) of the best performing device.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate the double perovskite solar cells with Cs2AgBiBr6 films that were initially prepared by single-source evaporation deposition. Further crystallized after post-annealing under high temperature, the Cs2AgBiBr6 films have the advantages of high crystallinity, good smoothness, and free pinholes. By incorporating Cs2AgBiBr6 films with suitable annealing conditions and film thickness, the solar cell devices represent an optimal PCE of 0.70%. The photovoltaic performance of this perovskite material is expected to be further enhanced by optimizing the energy alignment of charge transporting materials to reduce the energy loss from the interface between perovskite and charge transporting materials. In addition, developing direct bandgap double perovskites by doping can also improve solar cell efficiency. The solar cell devices based on high-quality Cs2AgBiBr6 films that were prepared by single-source evaporation deposition suggest that this perovskite material can be a potential candidate for environmentally friendly photovoltaic application.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/9/12/1760/s1, Figure S1: SEM image of Cs2AgBiBr6 crystal with typical octahedral morphology; Figure S2: Thermogravimetric analysis of Cs2AgBiBr6 powder; Figure S3: SEM surface morphology of Cs2AgBiBr6 film thermally annealed at 350 °C for 30 min; Figure S4: XRD pattern of Cs2AgBiBr6 film thermally annealed at 350 °C for 30 min. The positions of reflections labeled by circle (•) and diamond (♦) indicate the additional phases of CsAgBr2 and Cs3Bi2Br9 respectively; Figure S5: The diffraction peak intensity of (220), (400) and (440) planes of Cs2AgBiBr6 films as a function of annealing temperature, respectively; Figure S6: The diffraction peak intensity of (220), (400) and (440) planes of Cs2AgBiBr6 films as a function of annealing time, respectively; Figure S7: Steady-state photoluminescence spectrum of Cs2AgBiBr6 crystal; Table S1: Device performance of Cs2AgBiBr6 films with different annealing time and temperatures; Figure S8: The statistical box charts of open-circuit voltage (Voc), short-circuit current density (Jsc) and fill factor (FF) of solar cells assembled with Cs2AgBiBr6 films (297 nm) annealed at 250 °C and 300 °C for different times respectively. The values were obtained from 16 individual devices per annealing condition; Table S2: Parameters of solar cell devices with different Cs2AgBiBr6 film thicknesses; Figure S9: The statistical box charts of open-circuit voltage (Voc), short-circuit current density (Jsc) and fill factor (FF) of solar cells based on Cs2AgBiBr6 films with various thin film thickness. The values were obtained from 16 individual devices per annealing condition; Figure S10: SEM surface morphology of Cs2AgBiBr6 film annealed at 300 °C for 15 min. The film thickness is approximately 167 nm. The areas marked by yellow circles indicate pinholes in the Cs2AgBiBr6 film. Figure S11. J-V curves of Cs2AgBiBr6 solar cell, measured by backward scan and forward scan. The Cs2AgBiBr6 film was prepared at 300°C for 30 min.

Author Contributions

Data curation, P.F., H.-X.P., G.-X.L.; methodology, H.-X.P., Z.-H.S., Z.-H.Z., Z.-H.C., X.-Y.C., Y.-D.L.; investigation, P.F., H.-X.P., Z.-H.S., S.-J.T., J.-T.L. and G.-X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.F., H.-X.P. and Z.-H.S.; funding acquisition, P.F. and G.-X.L.; funding acquisition, G.-X.L.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology plan project of Shenzhen, JCYJ20180305124340951 and Key Project of Basic Research of Education in Guangdong, 2018KZDXM059 and National Natural Science Foundation of China, 61404086 and 11574217 and Shenzhen Key Lab Fund, ZDSYS 20170228105421966.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Xing G., Mathews N., Sun S., Lim S.S., Lam Y.M., Grätzel M., Mhaislkar S., Sum T.C. Long-range balanced electron-and hole-transport lengths in organic-inorganic CH3NH3PbI3. Science. 2013;342:344–347. doi: 10.1126/science.1243167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stranks S.D., Eperon G.E., Grancini G., Menelaou C., Alcocer M.J.P., Leijtens T., Herz L.M., Petrozza A., Snaith H.J. Electron-hole diffusion lengths exceeding 1 micrometer in an organometal trihalide perovskite absorber. Science. 2013;342:341–344. doi: 10.1126/science.1243982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NREL Efficiency Chart. [(accessed on 17 April 2019)]; Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html.

- 4.Kumar M.H., Dharani S., Leong W.L., Boix P.P., Prabhakar R.R., Baikie T., Shi C., Ding H., Ramesh R., Aata M., et al. Lead-free halide perovskite solar cells with high photocurrents realized through vacancy modulation. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:7122–7127. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slavney A.H., Hu T., Lindenberg A.M., Karunadasa H.I. A bismuth-halide double perovskite with long carrier recombination lifetime for photovoltaic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2138–2141. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang B., Lei Y., Qi R., Yu H., Yang X., Cai T., Zheng Z. An in-situ room temperature route to CuBiI4 based bulk-heterojunction perovskite-like solar cells. Sci. China Mater. 2019;62:519–526. doi: 10.1007/s40843-018-9355-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thong H.C., Zhao C., Zhu Z.X., Chen X., Li J.F., Wang K. The impact of chemical heterogeneity in lead-free (K, Na) NbO3 piezoelectric perovskite: Ferroelectric phase coexistence. Acta Mater. 2019;166:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2019.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao F., Stoumpos C.C., Cao D.H., Chang R.P.H., Kanatzidis M.G. Lead-free solid-state organic-inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics. 2014;8:489–494. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ran C., Wu Z., Xi J., Yuan F., Dong H., Lei T., He X., Hou X. Construction of Compact Methylammonium Bismuth Iodide Film Promoting Lead-Free Inverted Planar Heterojunction Organohalide Solar Cells with Open-Circuit Voltage over 0.8 V. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017;8:394–400. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang F., Yang D., Jiang Y., Liu T., Zhao X., Ming Y., Luo B., Qin F., Fan J., Han H., et al. Chlorine-Incorporation-Induced Formation of the Layered Phase for Antimony-Based Lead-Free Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1019–1027. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volonakis G., Filip M.R., Haghighirad A.A., Sakai N., Wenger B., Snaith H.J., Giustino F. Lead-Free Halide Double Perovskite via Heterovalent Substitution of Noble Metals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:1254–1259. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creutz S.E., Crites E.N., Gamelin D.R. Colloidal nanocrystals of lead-free double-perovskite (Elpasolite) semiconductors: Synthesis and anion exchange to access new materials. Nano Lett. 2018;18:1118–1123. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu L., Ahmad W., Liu W., Yang J., Zhang R., Sun Y., Yang J., Li X. Lead-free halide double perovskite materials: A new superstar toward green and stable optoeletronic applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2019;11:16. doi: 10.1007/s40820-019-0244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan W., Wu H., Luo J., Deng Z., Ge C., Chen C., Jiang X., Yin W.J., Niu G., Zhu L., et al. Cs2AgBiBr6 single-crystal X-ray detectors with a low detection limit. Nat. Photonics. 2017;11:726–732. doi: 10.1038/s41566-017-0012-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClure E.T., Ball M.R., Windl W., Woodward P.M. Cs2AgBiX6 (X = Br, Cl): New visible light absorbing, lead-free halide perovskite semiconductors. Chem. Mater. 2016;28:1348–1354. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b04231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao Z., Meng W., Wang J., Yan Y. Thermodynamic stability and defect chemistry of bismuch-based lead-free double perovskites. ChemSusChem. 2016;9:2628–2633. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201600771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filip M.R., Hillman S., Haghighirad A.A., Snaith H.J., Giustino F. Band gaps of the lead-free halide double perovskite Cs2BiAgCl6 and Cs2BiAgBr6 from theory and experiment. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:2579–2585. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ning W., Wang F., Wu B., Lu J., Yan Z., Liu X., Tao Y., Liu J.M., Huang W., Fahlman M., et al. Long electron-hole diffusion length in high-quality lead-free double perovskite films. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1706246. doi: 10.1002/adma.201706246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C., Zhang Q., Liu Y., Luo W., Guo X., Huang Z., Ting H., Sun W., Zhong X., Wei S., et al. The dawn of lead-free perovskite solar cell: Highly stable double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 film. Adv. Sci. 2018;5:1700759. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao W., Ran C., Xi J., Jiao B., Zhang W., Wu M., Hou X., Wu Z. High-quality Cs2AgBiBr6 double perovskite film for lead-free inverted planar heterojunction solar cells with 2.2% efficiency. ChemPhysChem. 2018;19:1696–1700. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201800346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greul E., Petrus M.L., Binek A., Docampo P., Bein T. Highly stable, phase pure Cs2AgBiBr6 double perovskite thin films for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:19972–19981. doi: 10.1039/C7TA06816F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang M., Zeng P., Bai S., Gu J., Li F., Yang Z., Liu M. High-quality sequential-vapor-deposited Cs2AgBiBr6 thin films for lead-free perovskite solar cells. Sol. RRL. 2018;2:1800217. doi: 10.1002/solr.201800217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igbari F., Wang R., Wang Z.K., Ma X.J., Wang Q., Wang K.L., Zhang Y., Liao L.S., Yang Y. Composition stoichiometry of Cs2AgBiBr6 films for highly efficient lead-free perovskite solar cells. Nano Lett. 2019;19:2066–2073. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du K., Meng W., Wang X., Yan Y., Mitzi D.B. Bandgap Engineering of Lead-Free Double Perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 through Trivalent Metal Alloying. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:8158–8162. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slavney A.H., Leppert L., Bartesaghi D., Gold-Parker A., Toney M.F., Savenije T.J., Neaton J.B., Karunadasa H.I. Defect-Induced Band-Edge Reconstruction of a Bismuth-Halide Double Perovskite for Visible-Light Absorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5015–5018. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eperon G.E., Burlakov V.M., Docampo P., Goriely A., Snaith H.J. Morphological control for high performance, solution-processed planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24:151–157. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201302090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q., Shao Y., Dong Q., Xiao Z., Yuan Y., Huang J. Large fill-factor bilayer iodine perovskite solar cells fabricated by a low-temperature solution-process. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014;7:2359–2365. doi: 10.1039/C4EE00233D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y.X., Zhu K. CH3NH3Cl-assisted one-step solution growth of CH3NH3PbI3: Structure, charge-carrier dynamics, and photovoltaic properties of perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:9412–9418. doi: 10.1021/jp502696w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H.B., Choi H., Jeong J., Kim S., Walker A., Song S., Kim J.Y. Mixed solvents for the optimization of morphology in solution-processed, inverted-type perovskite/fullerene hybrid solar cells. Nanoscale. 2014;6:6679–6683. doi: 10.1039/c4nr00130c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan P., Gu D., Liang G.X., Luo J.T., Chen J.L., Zheng Z.H., Zhang D.P. High-performance perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 thin films for solar cells prepared by single-source physical vapour deposition. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29910. doi: 10.1038/srep29910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longo G., Gil-Escrig L., Degen M.J., Sessolo M., Bolink H.J. Perovskite solar cells prepared by flash evaporation. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:7376–7378. doi: 10.1039/C5CC01103E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu H., Zhang S., Zhao H., Will G., Liu P. An efficient and low-cost TiO2 compact layer for performance improvement of dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta. 2008;54:1319–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bekenstein Y., Dahl J.C., Huang J., Osowiecki W.T., Swabeck J.K., Chan E.M., Yang P., Alivisatos A.P. The Making and Breaking of Lead-Free Double Perovskite Nanocrystals of Cesium Silver–Bismuth Halide Compositions. Nano Lett. 2018;6:3502–3508. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You J., Yang Y., Hong Z., Song T.B., Meng L., Liu Y., Jiang C., Zhou H., Chang W.H., Li G., et al. Moisture assisted perovskite film growth for high performance solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;105:183902. doi: 10.1063/1.4901510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang B., Chen J., Yang S., Hong F., Sun L., Han P., Pullerits T., Deng W., Han K. Lead-free silver-bismuth halide double perovskite nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. 2018;57:5359–5363. doi: 10.1002/anie.201800660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo Z., Wan Y., Yang M., Snaider J., Zhu K., Huang L. Long-range hot-carrier transport in hybrid perovskites visualized by ultrafast microscopy. Science. 2017;356:59–62. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang B., Mao X., Hong F., Meng W., Tang Y., Xia X., Yang S., Deng W., Han K. Lead-free direct band gap double-perovskite nanocrystals with bright dual-color emission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:17001–17006. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b07424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung H., Jung S.I., Kim H.J., Cha W., Sim E., Kim D., Koh W.K., Kim J. Composition-dependent hot carrier relaxation dynamics in cesium lead halide (CsPbX3, X = Br and I) perovskite nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:4160–4164. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang B., Chen J., Hong F., Mao X., Zheng K., Yang S., Li Y., Pullerits T., Deng W., Han K. Lead-free, air-stable all-inorganic cesium bismuth halide perovskite nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. 2017;56:12471–12475. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eames C., Frost J.M., Barnes P.R.F., O’Regan B.C., Walsh A., Islam M.S. Ionic transport in hybrid lead iodide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7497–7504. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.