Abstract

In-line purification is an important tool for flow chemistry. It enables effective handling of unstable intermediates and integration of multiple synthetic steps. The integrated flow synthesis is useful for drug synthesis and process development in medicinal chemistry. In this article, we overview current states of in-line purification methods. In particular, we focus on four common methods: scavenger column, distillation, nanofiltration, and extraction. Examples of their applications are provided.

Keywords: Flow chemistry, flow synthesis, in-line purification, continuous separation; drug synthesis

In the early decades of drug discovery, medicinal chemistry relied on in vivo testing of a limited set of potential therapeutical molecules. However, after the 1980s, drug discovery has been accelerated by many technologies such as high-throughput in vitro screening and receptor-based pharmacology.1 At the same time, characterization methods have been greatly developed, allowing for extensive studies of synthetic routes. Consequently, such advances in pharmacological testing and characterization have resulted in the rapid growth of new pharmaceutical entities.

In response to the increasingly large compound libraries, engineering work has progressed in order to enable efficient drug synthesis and process development. Traditionally, molecules are synthesized in batch. However, the batchwise approach can be time-consuming and inefficient. A number of reactions suffer from slow mass transfer, which in turn results in limited apparent kinetics.2 Some highly exothermic reactions are difficult to operate in batch due to slow heat dissipation from a batch reaction unit.3 Moreover, a batch process also has several logistical disruptions such as material transfers between reaction units. This aspect renders a batch process unsuitable for high-throughput screening as well as synthesis that involves unstable or air-sensitive intermediates.4−6

Flow chemistry has emerged as an approach that addresses the above-mentioned challenges. This technique is closely related to the concept of microreaction in which a particular transformation occurs as it flows through a micron-sized channel. In particular, flow chemistry refers to the methodology in which reactions are performed in tube reactors rather than fabricated microreactors.7 Flow chemistry and microreaction offer many similar benefits, including increased mass and heat transfer, which in turn allows for a more efficient process, smaller reaction unit size, and greater safety. In some cases, reactions are more efficient in flow than batch such as multiphase reactive systems.8 Flow system also means that chemicals are handled and synthesized continuously, eliminating challenges caused by the disconnected nature of batchwise operations.

As a result, both flow chemistry and microfluidics continue to expand in applications in chemical synthesis. In the past, microreactors have been used to study reaction mechanisms and obtain kinetic information.9,10 Furthermore, with its efficient process, flow chemistry is useful for generations of a large set of compounds, particularly in serial parallel solution-based organic syntheses as well as combinatorial chemistry.11 In the flow systems, process parameters such as reaction time and temperature can be precisely regulated. Therefore, drug candidates with specific bioactivity-focused structures can be produced via assembly of building blocks and known chemical reactions. Alternatively, flow synthesis can be integrated with computational target prediction to facilitate medicinal chemists in producing drug candidates.12 Recently, researchers at MIT have developed a flow synthesis platform that uses software to identify possible synthetic routes for a target molecule and control a robotic arm to assemble units (e.g., reactors).13

Aside from automated drug synthesis, process development can also benefit from a flow chemistry approach. During the process development phase, engineers aim to obtain optimal operating conditions for synthesizing a target drug. Many works have reported the use of automated microfluidic systems for optimizing reaction conditions.14−18 Process variables, either continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration) or discrete variables (e.g., solvent and catalyst types), can be adjusted in an adaptive response to inline or online analytical results such as a LC/MS, a FTIR monitoring, and a UV–vis spectrometer. A similar concept for automated synthesis optimization and data acquisition was applied for continuous-flow reactors.19

Furthermore, a flow approach is beneficial to multistep synthesis. Drug molecules are complex and need to be transformed stepwise from simple precursors. Therefore, the synthesis of most drug compounds contains multiple steps of reactions. A flow system allows unstable intermediate to be transferred rapidly to a subsequent step. General examples of multistep organic synthesis in flow have been comprehensively overviewed.20 Steps are often arranged sequentially although some of them can be carried out in parallel in order to produce different intermediates. In our perspective, multistep synthesis in flow can be developed by three approaches, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schemes show different approaches for operating multistep synthesis in flow: (1) telescoping, (2) integration with off-line purification, (3) integration with in-line purification.

The first approach is to telescope multiple reactions or adjust reaction conditions such that all the steps are compatible. Solvents, excess reagents, products, and side products need to be considered. Examples include the syntheses of Ibuprofen,21 CCR8 ligands,22 Rolipram,23 and Lidocaine.24 This approach is simple to implement since it does not require any purification. However, telescoping multistep synthesis becomes more difficult as the number of steps increases. The second approach handles the intermediate purification off-line. Therefore, multistep synthesis via this approach is not fully continuous. Off-line purification methods include batch extraction, rotary evaporation, and chromatography. Off-line purification has major disadvantages of being time-consuming and unsuitable for highly reactive or unstable intermediates. In the third approach, all the purification steps are done in-line and continuously. In-line purification can separate impurities out from the main stream or remove excess reagents that may not be compatible with the subsequent reactive step. In this innovation article, we will overview the state-of-the-art techniques for in-line purification, particularly for applications in flow chemistry. There are four common methods that will be discussed, namely scavenger column, distillation, nanofiltration, and extraction.

To begin with, use of scavenger resins has been of great interest to many synthetic chemists because of its simplicity to separate desired and undesired compounds. Often, impurities will experience either an electrostatic or covalent interaction with the resins, so that they can be isolated from the solution.25 In batch, filtration can be employed to separate the resin-bound impurities from the product in the solution.26 In flow, the resins are packed in a column; hence, the products remain in the reaction stream. Over the past decades, many examples of scavenger resins have been demonstrated in flow chemistry.27 For example, the immobilized benzyl amine resins were used to remove isocyanide and acid chlorides, which were in excess during the preparation of oxazole derivatives.28 The authors also showed that the immobilized phosphene resins could scavenge residual azide, which was a starting material in the process.29 In another example, Omnifit glass tubes were used to pack scavenger materials for the multistep synthesis of triazoles and incorporated into the commercial flow-synthesis platform, Vaportec R2+/R4,30 as shown in Figure 2. In the system, the resins, Quadrapure-benzylamine (QP-BZA) and Quadrapure-thiourea (QP-TU), removed excess aldehyde and any leached copper. The base Amberlyst A-21, immobilized on polymer resins, was employed to catch unreacted carboxylic acid during the racemic resolution of flurbiprofen.31

Figure 2.

(a) Scheme of the triazoles synthesis with scavenger resins to remove impurities. (b) Vaportec R2+/R4 with scavengers in glass columns. Adapted with permission from ref (30). Copyright 2009 Wiley-VCH.

Second, distillation is another method that has been used in flow chemistry. One of the early developments is vacuum membrane distillation on a microfluidic chip.32 In such a unit, a membrane layer is sandwiched between two channels, and serves as liquid-vapor contact. Methanol–water separation was achieved in the unit. Similarly, the microfluidic distillation from Klavs F. Jensen’s group was demonstrated for solvent switch from dichloromethane to N,N-dimethylformamide between sequential reactive steps33 (Figure 3a). Moreover, continuous reactive distillation could also be performed using a simple glassware setup with a Hickman still head.34 The head had two ports, top and side. The intermediate was continuously withdrawn by a pump through the side port and sent to the subsequent reaction directly (Figure 3b). A closely related device is an in-line evaporator for concentrating or switching solvent during the flow process. The in-line evaporator was prototyped by Steven Ley’s group using a glass column and metal fittings35 (Figure 3c). The prototype was successfully implemented for solvent switch from toluene to methanol in a telescoped flow synthesis.

Figure 3.

(a) Microfluidic distillation for in-line solvent switch. Adapted with permission from ref (33). Copyright 2010 Wiley-VCH. (b) Hickman still head setup for continuous reactive distillation. Reproduced from ref (34) with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry. (c) Prototype glass column for solvent switch. Adapted from ref (35) with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Third, nanofiltration is a promising in-line purification that is based on molecule sizes. In the past, nanofiltration has been applied to facilitate solvent switch,36,37 recovery of catalysts and solvent,38,39 as well as removal of impurities.40 Recently, it has been found useful for the development of continuous synthesis, thanks to the progress in membrane materials and properties such as organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN). Gursel et al. (2015) overviewed several examples that employed OSN for recovery of homogeneous catalysts in continuous-flow process41. As an example, sustainability of the continuous-flow Michael addition process was improved by operating the in situ OSN to recover and recycle solvent and excess reagent.42 As a relatively young area, OSN has begun to be used in pharmaceutical synthesis. For instance, as shown in Figure 4a, a flow-through reactor/separator assembly was built with the polymeric OSN membrane to separate the Pd catalyst from the Heck coupling reactions.43 Similarly, the same research group also implemented two stages of OSN to separate a desired API, Roxithromycin, from a potential genotoxic impurity, 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP).44 Their design achieved a purity of 99% or greater. The use of Puramem 280, a commercial membrane for OSN (Figure 4 b), was reported for its function to separate and recycle metathesis catalysts in the flow setup.45 Their work has proved that the flow system could separate the catalyst at 99.0–99.8% rejection, which was similar in performance to the large-scale batch filtration.

Figure 4.

(a) Continuous-flow reactor/separator cell assembly for performing Heck coupling reactions and separating Pd catalysts. Adapted with permission from ref (43). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (b) Nanofiltration module for separating metathesis catalysts. Reprinted with permission from ref (45). Copyright 2014 Wiley-VCH.

Lastly, liquid extraction is a method to separate desired solutes from impurities, based on their different solubilities in liquids. As it involves liquid, this method can be made continuous. For applications in medicinal chemistry, extraction has been integrated with synthesis for two main applications: final and intermediate purifications. For the former application, continuous extraction is installed at the end of a flow synthesis to purify the final compound before using or sending to further downstream processing or formulation.46−49 On the other hand, the intermediate extraction is in between reactive steps in order to remove any impurities, including byproducts and excess reagents, from the desired intermediate.24,50−52 Researchers at MIT integrated in-line extraction with three reactive steps under pressure of 1.7 MPa in order to synthesize fluoxetine24 as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Integrated multistep synthesis of fluoxetine with in-line membrane separations. From ref (24). Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

In the past decade, different designs of continuous extractors have been reported. The common designs are based on either a gravity or capillary force. The gravity-based extractor is similar to a conventional mixer-settler, but with a smaller volume. As shown in Figure 6a, a prototype high-efficiency extraction device (HEED) has been developed.53 The device passed liquid streams to sparge-like adapters in order to generate thin streams into the glass column, where the light and heavy phases settled down as top and bottom layers, respectively. In some cases, a level detector is needed to maintain the position of the interface between the two layers such that the streams can be continuously pumped in and out. An electrical impedance probe could be used to control the phase separation between organic and aqueous phases,54 as shown in Figure 6b. Another example monitored a position of a floating ball using a camera and a feedback control system.55 This type of camera-based systems has been implemented for in-line extraction in many reactions including hydrazone formations55,56 and iodination.57

Figure 6.

(a) High-efficiency extraction device in a glass column. Adapted with permission from ref (53). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. (b) Use of electrical impedance probe to monitor the phase separation in a glass tube. Adapted by permission from Springer, Journal of Flow Chemistry, Sprecher, H.; Payán, M. N. P.; Weber, M.; Yilmaz, G.; Wille, G., Copyright 2012. (c) Flow setup with a camera-based separator for hydrozone formations. Adapted from 55 with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

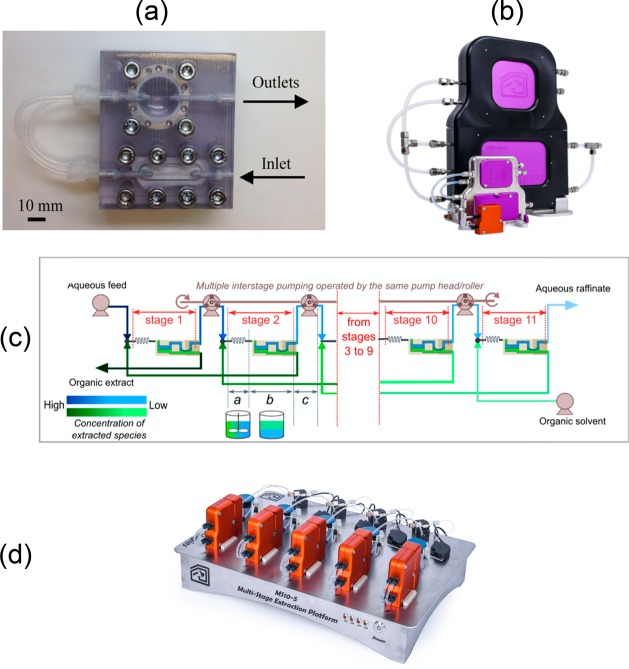

Alternatively, the extractor can take advantage of surface forces. In 2007, a membrane-based microfluidic extraction device was developed by Krajl et al.58 The main part of the device is a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane that selectively wets only nonaqueous phase and enables the separation between the aqueous and organic streams after their mixing in the tube. Pressure drop across the membrane must be balanced to ensure complete separation.59 Microfluidic extraction was integrated with a microreactor to perform a multistep continuous-flow microchemical synthesis.60 Related approaches have been reported using different geometries of the separator, including a porous capillary61−63 and a slit shape.64 To eliminate the need for manual control of the pressure drop across the membrane, Adamo et al. (2013) integrated a self-tuning pressure regulator to Krajl’s design. The regulator relies on a similar concept as a valve that can close or open a fluid channel. This allows the device to build up the pressure drop just enough to force only a wetting phase through the membrane65 (Figure 7a). The device has now been marketed by Zaiput Flow Technologies (Figure 7b). As a simple plug-and-play device, this membrane separator has been useful in continuous drug synthesis.24,46,66−68 Apart from drug production, it has also found many applications such as flow chemistry,69,70 separation of radioisotopes,71 and gas–liquid separation.72 The membrane separator has also been configured as multistage countercurrent extraction to improve the extraction efficiency,73−75 as shown in Figure 7c. Similarly, the setup has now been commercialized by Zaiput Flow Technologies, as shown in Figure 7d. Besides the membrane separator, some other examples of the multistage extraction setups have been reported.76,77

Figure 7.

(a) Prototyped membrane separator with self-tuning pressure control. Reprinted with permission from ref (65). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (b) Membrane separators as commercialized by Zaiput Flow Technologies. Copyright Andrea Adamo. Used with permission. (c) Continuous-flow multistage extraction setup. Reprinted with permission from ref (73). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society. (d) Multistage setup on market by Zaiput Flow Technologies. Copyright Andrea Adamo. Used with permission.

In conclusion, this article provides an overview of current technologies for in-line purification that can be incorporated in continuous-flow synthesis. We discussed four techniques: scavenger resins, distillation, nanofiltration, and extraction. They are potential tools for drug synthesis. They can be implemented for diverse applications including removal of impurities, separation of volatile components/solvents, isolation, and recycling of catalysts. However, each of these techniques has its own challenges. For the scavenger resins, the resins need to be carefully chosen in order to have a high selectivity toward binding only impurities, and not a product. Moreover, the resins may be saturated after some time, so the flow synthesis needs to be stopped in order to replace the column. For in-line distillation/evaporation, the precipitation of the residue materials on the evaporator wall has been reported.35 Gas expansion can cause an unsteady flow, making it difficult to implement in between reactors that require a steady flow. Likewise, there are a number of challenges with nanofiltration such as chemical incompatibility of the membranes, membrane fouling, insufficient rejection of solutes, and limited lifetime of the membranes.78 Lastly, liquid extraction may also have limitations in some cases such as systems with an emulsion layer and those with a very low interfacial tension. It is sometimes challenging to choose an optimal solvent that has a high selectivity toward key solutes as well as a compatibility with all species in the stream.

As for future prospects, we expect that there will be developments of the devices that enable diverse applications at once. Ideally, a unit could be inserted into any synthetic route without the need for time-consuming customization or optimization. These types of ideal units can be used also in automated systems for drug-compound generations or process development. Higher selectivities can be achieved via improvements in chemical and engineering aspects. For example, different resins should be developed to enhance selectivity; alternatively, units can be arranged in multistage fashion to increase a level of separation.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Weeranoppanant’s research has been supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (grant number: 5.9/2562).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Lombardino J. G.; Lowe J. A. III A guide to drug discovery: the role of the medicinal chemist in drug discovery—then and now. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2004, 3 (10), 853. 10.1038/nrd1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman R. L.; McMullen J. P.; Jensen K. F. Deciding whether to go with the flow: evaluating the merits of flow reactors for synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50 (33), 7502–7519. 10.1002/anie.201004637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. G.; Jensen K. F. The role of flow in green chemistry and engineering. Green Chem. 2013, 15 (6), 1456–1472. 10.1039/c3gc40374b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P. R.; Browne D. L.; Pastre J. C.; Butters C.; Guthrie D.; Ley S. V. Continuous flow-processing of organometallic reagents using an advanced peristaltic pumping system and the telescoped flow synthesis of (E/Z)-tamoxifen. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17 (9), 1192–1208. 10.1021/op4001548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huck L.; de la Hoz A.; Díaz-Ortiz A.; Alcázar J. Grignard Reagents on a Tab: Direct Magnesium Insertion under Flow Conditions. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (14), 3747–3750. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton M.; Huck L.; Alcazar J. On-demand synthesis of organozinc halides under continuous flow conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13 (2), 324. 10.1038/nprot.2017.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K. F. Flow chemistry—microreaction technology comes of age. AIChE J. 2017, 63 (3), 858–869. 10.1002/aic.15642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weeranoppanant N. Enabling tools for continuous-flow biphasic liquid–liquid reaction. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 4 (2), 235–243. 10.1039/C8RE00230D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen J. P.; Jensen K. F. Rapid determination of reaction kinetics with an automated microfluidic system. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2011, 15 (2), 398–407. 10.1021/op100300p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aroh K. C.; Jensen K. F. Efficient kinetic experiments in continuous flow microreactors. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 3 (1), 94–101. 10.1039/C7RE00163K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich P. S.; Manz A. Lab-on-a-chip: microfluidics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5 (3), 210. 10.1038/nrd1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G. Automating drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17 (2), 97. 10.1038/nrd.2017.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley C. W.; Thomas D. A. 3rd; Lummiss J. A. M.; Jaworski J. N.; Breen C. P.; Schultz V.; Hart T.; Fishman J. S.; Rogers L.; Gao H.; Hicklin R. W.; Plehiers P. P.; Byington J.; Piotti J. S.; Green W. H.; Hart A. J.; Jamison T. F.; Jensen K. F., A robotic platform for flow synthesis of organic compounds informed by AI planning. Science 2019, 365 ( (6453), ), eaax1566. 10.1126/science.aax1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen J. P.; Jensen K. F. An automated microfluidic system for online optimization in chemical synthesis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2010, 14 (5), 1169–1176. 10.1021/op100123e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. S.; Jensen K. F. Automated multitrajectory method for reaction optimization in a microfluidic system using online IR analysis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012, 16 (8), 1409–1415. 10.1021/op300099x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reizman B. J.; Jensen K. F. Feedback in flow for accelerated reaction development. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49 (9), 1786–1796. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reizman B. J.; Wang Y.-M.; Buchwald S. L.; Jensen K. F. Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling optimization enabled by automated feedback. Reaction chemistry & engineering 2016, 1 (6), 658–666. 10.1039/C6RE00153J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rifai N.; Cao E.; Dua V.; Gavriilidis A. Microreaction technology aided catalytic process design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2013, 2 (3), 338–345. 10.1016/j.coche.2013.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes N.; Akien G. R.; Savage R. J.; Stanetty C.; Baxendale I. R.; Blacker A. J.; Taylor B. A.; Woodward R. L.; Meadows R. E.; Bourne R. A. Online quantitative mass spectrometry for the rapid adaptive optimization of automated flow reactors. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2016, 1 (1), 96–100. 10.1039/C5RE00083A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner J.; Ceylan S.; Kirschning A. Flow chemistry–a key enabling technology for (multistep) organic synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354 (1), 17–57. 10.1002/adsc.201100584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan A. R.; Poe S. L.; Kubis D. C.; Broadwater S. J.; McQuade D. T. The continuous-flow synthesis of ibuprofen. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48 (45), 8547–8550. 10.1002/anie.200903055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. P.; Mirsharghi S.; Rummel P. C.; Thiele S.; Rosenkilde M. M.; Ritzén A.; Ulven T. Multistep Continuous-Flow Synthesis in Medicinal Chemistry: Discovery and Preliminary Structure–Activity Relationships of CCR8 Ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19 (28), 9343–9350. 10.1002/chem.201204350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubogo T.; Oyamada H.; Kobayashi S. Multistep continuous-flow synthesis of (R)-and (S)-rolipram using heterogeneous catalysts. Nature 2015, 520 (7547), 329. 10.1038/nature14343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo A.; Beingessner R. L.; Behnam M.; Chen J.; Jamison T. F.; Jensen K. F.; Monbaliu J.-C. M.; Myerson A. S.; Revalor E. M.; Snead D. R. On-demand continuous-flow production of pharmaceuticals in a compact, reconfigurable system. Science 2016, 352 (6281), 61–67. 10.1126/science.aaf1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxendale I. R. The integration of flow reactors into synthetic organic chemistry. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 88 (4), 519–552. 10.1002/jctb.4012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seeberger P. H. Organic synthesis: scavengers in full flow. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1 (4), 258. 10.1038/nchem.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R. M.; Roper K. A.; Baxendale I. R.; Ley S. V. The evolution of immobilized reagents and their application in flow chemistry for the synthesis of natural products and pharmaceutical compounds. Modern Tools for the Synthesis of Complex Bioactive Molecules 2012, 359–393. 10.1002/9781118342886.ch11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M.; Baxendale I. R.; Ley S. V.; Smith C. D.; Tranmer G. K. Fully automated continuous flow synthesis of 4, 5-disubstituted oxazoles. Org. Lett. 2006, 8 (23), 5231–5234. 10.1021/ol061975c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. D.; Baxendale I. R.; Lanners S.; Hayward J. J.; Smith S. C.; Ley S. V. [3+ 2] Cycloaddition of acetylenes with azides to give 1, 4-disubstituted 1, 2, 3-triazoles in a modular flow reactor. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5 (10), 1559–1561. 10.1039/b702995k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxendale I. R.; Ley S. V.; Mansfield A. C.; Smith C. D. Multistep synthesis using modular flow reactors: Bestmann–Ohira reagent for the formation of alkynes and triazoles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48 (22), 4017–4021. 10.1002/anie.200900970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamborini L.; Romano D.; Pinto A.; Bertolani A.; Molinari F.; Conti P. An efficient method for the lipase-catalysed resolution and in-line purification of racemic flurbiprofen in a continuous-flow reactor. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2012, 84, 78–82. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2012.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Kato S.; Anazawa T. Vacuum membrane distillation on a microfluidic chip. Chem. Commun. 2009, (19), 2750–2752. 10.1039/b823499j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman R. L.; Naber J. R.; Buchwald S. L.; Jensen K. F. Multistep microchemical synthesis enabled by microfluidic distillation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49 (5), 899–903. 10.1002/anie.200904634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M. Integrating reactive distillation with continuous flow processing. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 4 (2), 368–371. 10.1039/C8RE00217G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deadman B. J.; Battilocchio C.; Sliwinski E.; Ley S. V. A prototype device for evaporation in batch and flow chemical processes. Green Chem. 2013, 15 (8), 2050–2055. 10.1039/c3gc40967h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chun-Te Lin J.; Livingston A. G. Nanofiltration membrane cascade for continuous solvent exchange. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62 (10), 2728–2736. 10.1016/j.ces.2006.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeva L.; Da Silva Burgal J.; Heckenast Z.; Brazy F.; Cazenave F.; Livingston A. Continuous consecutive reactions with inter-reaction solvent exchange by membrane separation. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128 (43), 13774–13777. 10.1002/ange.201607795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra H. P.; Van Klink G. P.; Van Koten G. The use of ultra-and nanofiltration techniques in homogeneous catalyst recycling. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35 (9), 798–810. 10.1021/ar0100778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreimann J. M.; Skiborowski M.; Behr A.; Vorholt A. J. Recycling homogeneous catalysts simply by organic solvent nanofiltration: new ways to efficient catalysis. ChemCatChem 2016, 8 (21), 3330–3333. 10.1002/cctc.201601018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Székely G.; Bandarra J.; Heggie W.; Sellergren B.; Ferreira F. C. Organic solvent nanofiltration: a platform for removal of genotoxins from active pharmaceutical ingredients. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 381 (1–2), 21–33. 10.1016/j.memsci.2011.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsel I. V.; Noël T.; Wang Q.; Hessel V. Separation/recycling methods for homogeneous transition metal catalysts in continuous flow. Green Chem. 2015, 17 (4), 2012–2026. 10.1039/C4GC02160F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fodi T.; Didaskalou C.; Kupai J.; Balogh G. T.; Huszthy P.; Szekely G. Nanofiltration-enabled in situ solvent and reagent recycle for sustainable continuous-flow synthesis. ChemSusChem 2017, 10 (17), 3435–3444. 10.1002/cssc.201701120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeva L.; Arbour J.; Livingston A. On the potential of organic solvent nanofiltration in continuous heck coupling reactions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17 (7), 967–975. 10.1021/op400073p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeva L.; da Silva Burgal J.; Valtcheva I.; Livingston A. G. Continuous purification of active pharmaceutical ingredients using multistage organic solvent nanofiltration membrane cascade. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2014, 116, 183–194. 10.1016/j.ces.2014.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal E. J.; Jensen K. F. Continuous nanofiltration and recycle of a metathesis catalyst in a microflow system. ChemCatChem 2014, 6 (10), 3004–3011. 10.1002/cctc.201402368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C.; Snead D. R.; Zhang P.; Jamison T. F. Continuous-flow synthesis and purification of atropine with sequential in-line separations of structurally similar impurities. J. Flow Chem. 2015, 5 (3), 133–138. 10.1556/1846.2015.00013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monbaliu J.-C. M.; Stelzer T.; Revalor E.; Weeranoppanant N.; Jensen K. F.; Myerson A. S. Compact and integrated approach for advanced end-to-end production, purification, and aqueous formulation of lidocaine hydrochloride. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20 (7), 1347–1353. 10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M.; Cooper D. Continuous Flow Liquid–Liquid Separation Using a Computer-Vision Control System: The Bromination of Enaminones with N-Bromosuccinimide. Synlett 2015, 27 (01), 164–168. 10.1055/s-0035-1560975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimanouchi T.; Kataoka Y.; Tanifuji T.; Kimura Y.; Fujioka S.; Terasaka K. Chemical conversion and liquid–liquid extraction of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose by slug flow microreactor. AIChE J. 2016, 62 (6), 2135–2143. 10.1002/aic.15201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla-Vechia L.; Reichart B.; Glasnov T.; Miranda L. S.; Kappe C. O.; de Souza R. O. A three step continuous flow synthesis of the biaryl unit of the HIV protease inhibitor Atazanavir. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11 (39), 6806–6813. 10.1039/C3OB41464G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibfarth F. A.; Johnson J. A.; Jamison T. F. Scalable synthesis of sequence-defined, unimolecular macromolecules by Flow-IEG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (34), 10617–10622. 10.1073/pnas.1508599112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu E.; Mangunuru H. P.; Telang N. S.; Kong C. J.; Verghese J.; Gilliland S. E. III; Ahmad S.; Dominey R. N.; Gupton B. F. High-yielding continuous-flow synthesis of antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14 (1), 583–592. 10.3762/bjoc.14.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C.; Saldarriaga A.; Tilley M.; Hunter H.; Organ M. G.; Wilson D. J. A Single-Stage, Continuous High-Efficiency Extraction Device (HEED) for Flow Synthesis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20 (10), 1738–1743. 10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher H.; Payán M. N. P.; Weber M.; Yilmaz G.; Wille G. Acyl azide synthesis and curtius rearrangements in microstructured flow chemistry systems. J. Flow Chem. 2012, 2 (1), 20–23. 10.1556/jfchem.2011.00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M.; Koos P.; Browne D. L.; Ley S. V. A prototype continuous-flow liquid–liquid extraction system using open-source technology. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10 (35), 7031–7036. 10.1039/c2ob25912e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M.; Cooper D. A.; Mhembere P. The continuous-flow synthesis of carbazate hydrazones using a simplified computer-vision controlled liquid–liquid extraction system. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57 (47), 5188–5191. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M.; Cooper D. A.; Dolan J. Continuous flow iodination using an automated computer-vision controlled liquid-liquid extraction system. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58 (9), 829–834. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kralj J. G.; Sahoo H. R.; Jensen K. F. Integrated continuous microfluidic liquid–liquid extraction. Lab Chip 2007, 7 (2), 256–263. 10.1039/B610888A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Weeranoppanant N.; Jensen K. F. Characterization and Modeling of the Operating Curves of Membrane Microseparators. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56 (42), 12184–12191. 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b03207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo H. R.; Kralj J. G.; Jensen K. F. Multistep continuous-flow microchemical synthesis involving multiple reactions and separations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46 (30), 5704–5708. 10.1002/anie.200701434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannock J. H.; Phillips T. W.; Nightingale A. M.; deMello J. C. Microscale separation of immiscible liquids using a porous capillary. Anal. Methods 2013, 5 (19), 4991–4998. 10.1039/c3ay41251b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T. W.; Bannock J. H.; deMello J. C. Microscale extraction and phase separation using a porous capillary. Lab Chip 2015, 15 (14), 2960–2967. 10.1039/C5LC00430F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannock J. H.; Lui T. Y. M.; Turner S. T.; deMello J. C. Automated separation of immiscible liquids using an optically monitored porous capillary. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 3 (4), 467–477. 10.1039/C8RE00023A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsel I. V.; Kurt S. K.; Aalders J.; Wang Q.; Noël T.; Nigam K. D.; Kockmann N.; Hessel V. Utilization of milli-scale coiled flow inverter in combination with phase separator for continuous flow liquid–liquid extraction processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 855–868. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo A.; Heider P. L.; Weeranoppanant N.; Jensen K. F. Membrane-based, liquid–liquid separator with integrated pressure control. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52 (31), 10802–10808. 10.1021/ie401180t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaman Z.; Sobreira T. J.; Mufti A.; Ferreira C. R.; Cooks R. G.; Thompson D. H. Rapid On-Demand Synthesis of Lomustine under Continuous Flow Conditions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019, 23 (3), 334–341. 10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Weeranoppanant N.; Thomas D. A.; Tahara K.; Stelzer T.; Russell M. G.; O’Mahony M.; Myerson A. S.; Lin H.; Kelly L. P. Advanced Continuous Flow Platform for On-Demand Pharmaceutical Manufacturing. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24 (11), 2776–2784. 10.1002/chem.201706004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vitis V.; Dall’Oglio F.; Pinto A.; De Micheli C.; Molinari F.; Conti P.; Romano D.; Tamborini L. Chemoenzymatic synthesis in flow reactors: a rapid and convenient preparation of captopril. ChemistryOpen 2017, 6 (5), 668–673. 10.1002/open.201700082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebl R.; Cantillo D.; Kappe C. O. Continuous generation, in-line quantification and utilization of nitrosyl chloride in photonitrosation reactions. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 4 (4), 738–746. 10.1039/C8RE00323H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin T. A.; Lazarus G. M.; Kelly C. B.; Leadbeater N. E. A Continuous-Flow Approach to 3, 3, 3-Trifluoromethylpropenes: Bringing Together Grignard Addition, Peterson Elimination, Inline Extraction, and Solvent Switching. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18 (10), 1253–1258. 10.1021/op500190j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K. S.; Imbrogno J.; Fonslet J.; Lusardi M.; Jensen K. F.; Zhuravlev F. Liquid–liquid extraction in flow of the radioisotope titanium-45 for positron emission tomography applications. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 3 (6), 898–904. 10.1039/C8RE00175H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sang L.; Tu J.; Cheng H.; Luo G.; Zhang J.. Hydrodynamics and mass transfer of gas–liquid flow in micropacked bed reactors with metal foam packing. AIChE J., 2019, 10.1002/aic.16803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weeranoppanant N.; Adamo A.; Saparbaiuly G.; Rose E.; Fleury C.; Schenkel B.; Jensen K. F. Design of multistage counter-current liquid–liquid extraction for small-scale applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56 (14), 4095–4103. 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b00434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peer M.; Weeranoppanant N.; Adamo A.; Zhang Y.; Jensen K. F. Biphasic catalytic hydrogen peroxide oxidation of alcohols in flow: scale-up and extraction. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20 (9), 1677–1685. 10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y.; Weeranoppanant N.; Xie L.; Chen Y.; Lusardi M. R.; Imbrogno J.; Bawendi M. G.; Jensen K. F. Multistage extraction platform for highly efficient and fully continuous purification of nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2017, 9 (23), 7703–7707. 10.1039/C7NR01826F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Jing S.; Luo Q.; Chen J.; Luo G. Bionic system for countercurrent multi-stage micro-extraction. RSC Adv. 2012, 2 (29), 10817–10820. 10.1039/c2ra21818f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holbach A.; Kockmann N. Counter-current arrangement of microfluidic liquid-liquid droplet flow contactors. Green Process. Synth. 2013, 2 (2), 157–167. 10.1515/gps-2013-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bruggen B.; Mänttäri M.; Nyström M. Drawbacks of applying nanofiltration and how to avoid them: a review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63 (2), 251–263. 10.1016/j.seppur.2008.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]