Abstract

The importance of physicochemical property calculation and measurement is well-established in drug discovery. In particular, lipophilicity predictions play a central role in target design and prioritization. While significant progress has been made in our ability to calculate both logP and logD, the quality of these predictions is limited by the size and diversity of the underlying data set. Access to diverse data sets and advanced models is often limited to large organizations or consortia, and they are not available to many students and practitioners of medicinal chemistry. A molecular matched pair analysis of median ΔlogD7.4 contributions for substituents commonly used in drug discovery programs at Genentech is reported. The results of this ΔlogD analysis are compiled into a single table, which we anticipate will be of use to practicing medicinal chemists.

Keywords: lipophilicity, matched molecular pairs, logD, ΔlogD

Lipophilicity is a critical parameter in drug design and development.1 Canonized in Lipinski’s rule of five, trends in lipophilicity often correlate with the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile of drugs, while high lipophilicity has been shown to correlate with attrition in the development phase.1−4 For these reasons, measurement of the partition coefficient (logP) or its pH-dependent variant, the distribution coefficient (logD), is now routine in the process of drug discovery.5

The ability to predict the logD of molecules is central to the process of target design, evaluation, and prioritization within a medicinal chemistry program. This notion is accentuated by data that suggest the optimal lipophilicity for drugs exists within a narrow range of logP = 1–3.1 Pioneering work by Hansch, Leo, and Rekker demonstrated that the total lipophilicity of a molecule can be calculated through summation of the lipophilicity of its constitutive fragments.6−12 Building on this work, a variety of methods now exist for the prediction of logP; a limitation of these methods is that they possess a “reasonable degree of error which is often systematic”.1,13,14 Advances in computing (e.g., machine learning) and use of large internal data sets have led to the creation of tailored models for lipophilicity prediction; however, these models are not broadly distributed or accessible to those at institutions with limited historical data.15 Owing to these factors, we surmised that a list of experimentally determined logD values for common molecular fragments based on a large, diverse, and pharmaceutically relevant set of compounds would provide value to medicinal chemists as a reference to aid in target design. While not allowing for an exact calculation of logD, such a list provides a generalized sense of lipophilic contributions of commonly employed substituents in the context of drug-like molecules.

Our approach to establish the lipophilicity contributions of functional groups leveraged Genentech logD data collected using the shake-flask method at pH 7.4 and an in-house molecular matched pairs (MMPs) application.5,16 MMP analysis has found use in the assessment of quantitative structure–activity relationships, including in studying the lipophilicity of substituents, although previous lipophilicity reports have been limited in scope.17−22 Using the MMP algorithm, lists of MMPs that differ by a defined functional group were generated, allowing for statistical analysis of the contribution to logD of that functional group. As ΔlogD for an MMP is expected to be highly dependent on the environment of substitution (e.g., in the case of H-to-Me substitutions, an MMP could represent quite diverse transformations, such as acid-to-ester or phenyl-to-tolyl changes), analysis was conducted at two different radii. Here, radius is defined as the number of bonds from the point of substitution in an MMP that must be preserved as a minimal, shared substructure when data from the analysis is compiled. The analysis presented here is based on radius values of zero and three and a substructure of phenyl. Radius = 0 means that the functional group in question can have any attachment to the matched pair parent molecule and no matched pairs would be excluded during analysis. A substructure of phenyl and radius = 3 means that the substitution is occurring specifically on a 1,4-disubstituted phenyl ring shared between the MMPs. While its use is well-established in the literature, the term ‘radius’ is often not well-defined. Thus, a schematic illustration of the concept of radius in the context of this work is provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S1).

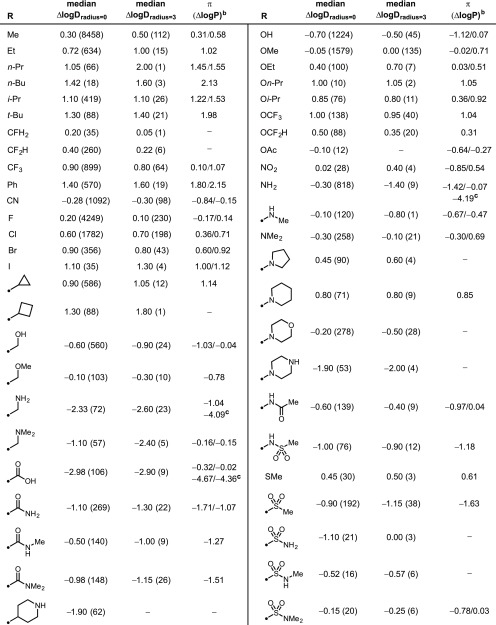

The median value for ΔlogD7.4 was chosen to limit the effects of experimental outliers, and the number of MMPs for a given functional group is provided in parentheses (Table 1). All ΔlogD7.4 values are compared with previously reported π-values (ΔlogP values for substituted benzene MMPs) from Hansch and Leo, when available; in cases where multiple values are listed, the minimum and maximum values are provided.7−9 Importantly, whereas the π-values provide data on a single, aryl-substituted MMP, this ΔlogD7.4 analysis provides a median measure of multiple MMPs of diverse, pharmaceutically relevant structure. In general, good agreement is observed between ΔlogD7.4 and π-values for nonionizable groups. Analysis of aliphatic fragments reveals that the lipophilic contributions of these functional groups is greater in MMPs with a radius = 3 than with a radius = 0. This trend is reversed for fluoroalkanes, which show reduced lipophilicity in MMPs with a radius = 3. For ionizable motifs, as expected the median ΔlogD7.4 falls between the ΔlogP of the un-ionized and completely ionized functional group, thus offering insight in to the median pKa values of these functional groups. For example, this analysis would suggest that primary amines and carboxylic acids in this library have median pKa values of approximately 8.7 and 4.5, respectively. As might be expected, there are fewer matched pairs at radius = 3 because, in this analysis, this would require matched pairs of only 1,4-disubstituted phenyl groups. Of perhaps greater note, although the logP data reported by Hansch and Leo are extensive, no values are provided for some fragments that are now frequently observed in drug-like compounds, perhaps reflective of the development of synthetic methods in the intervening period.7−9

Table 1. Lipophilic Contributions of Common Functional Groupsa.

logD measured by the shake-flask method at pH 7.4. Values in parentheses denote the number of MMPs for a given functional group at a given radius.

π-Values reported by Hansch and Leo.6−12 In cases where multiple data values were reported, they are expressed in the form minimum/maximum reported value.

π-Values for the ionized form of the functional group.

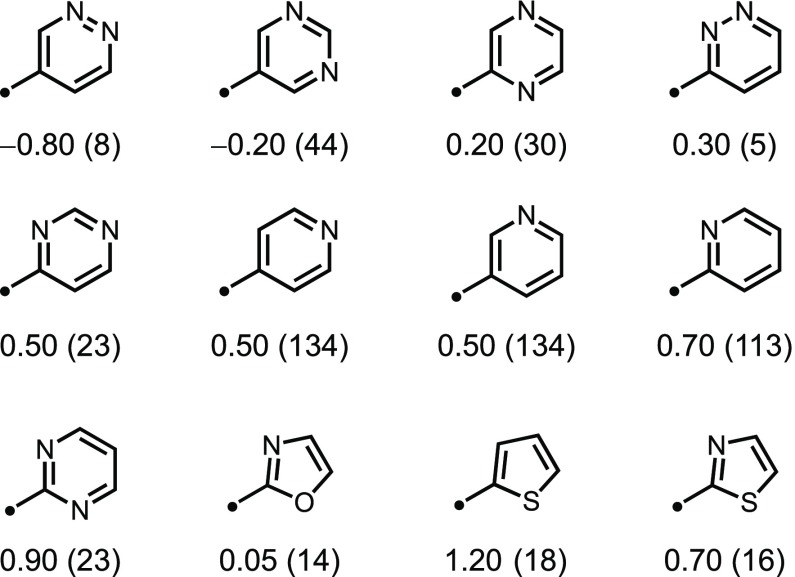

Phenyl substitution is one of the most lipophilic changes studied in this analysis, and bioisosteric replacement of this motif is a routine means of reducing compound lipophilicity.23,24 Common phenyl bioisosteres include nitrogen-containing analogues of benzene such as pyridines and diazines. Analysis of the lipophilic contributions of these heterocycles was performed and found to span nearly a 2-log-unit range, including 3-pyridazine, which decreases lipophilicity by −0.80 units (Figure 1). These data provide a quantitative assessment of the lipophilicity of common phenyl replacements.

Figure 1.

Median ΔlogD values measured at pH 7.4 for common heterocycles. Analysis performed between MMPs (heterocycle- vs H-substituted) with radius = 0, and the number of MMPs is shown in parentheses.

Cognizant of the observed standard deviation (see Table S1) for various substituents as well as variability in data measurements and its possible effect on our analyses, we sought to more closely scrutinize the underlying experimental data for median ΔlogD7.4. To this end, a detailed case study on trifluoromethyl MMPs was conducted which examined the most extreme outliers within this data set (compounds 1–6, Figure 2). The global maximum and minimum for ΔlogD7.4 of a trifluoromethyl substituent were +2.0 and −2.2, belonging to the MMPs of 3 to 4 and 5 to 6, respectively (Figure 2, top). Given that these experimental measures are subject to error, a reassessment of these outliers was undertaken and produced data in closer agreement with the median ΔlogD7.4 (+1.1, in both cases). The measured logP of these compounds is in good agreement with the remeasured logD7.4 for compounds 4 and 6, while for compound 2, the discrepancy between logD7.4 and logP can be explained through a change in the measured pKa of its aryl sulfonamide (ΔpKa = −0.7 for 1 to 2). Postulating that a source of error in these initial logD measurements might arise from poor solubility, the kinetic solubility of each of these compounds was tested. The observed error in initial logD measurement correlated with decreased solubility, in line with the necessity for compound solubility in logD determination by the shake-flask method.25 This observation led to two questions: (1) could variability in logD measurements be mitigated by filtering out compounds with limited solubility, and (2) would filtering by solubility affect median ΔlogD7.4? To this end, functional group data sets were filtered with kinetic solubility limits of >25 and >100 μM, resulting in a decrease in the standard deviation for ΔlogD7.4 without a notable effect on median ΔlogD7.4 (Figure 2, bottom). This effect was widely observed among the functional groups tested and demonstrates that (1) limited solubility is correlated with error in logD7.4 measurement and (2) removing outliers through filtering by solubility tightens standard deviation while not meaningfully changing median ΔlogD7.4. Further data and additional statistics for ΔlogD contributions of all substituents shown in Table 1 are provided in the Supporting Information (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Top: Lipophilicity, solubility, and acidity data for outlier CF3-MMPs at radius = 3. Bottom: Median and mean values for ΔlogD among CF3-MMPs at radius = 0 (left) and radius = 3 (right), along with statistical data for the same data sets filtered by kinetic solubility thresholds of >25 and >100 μM. Kin. Sol. = kinetic solubility, SD = standard deviation, Count = number of MMPs, and rad = radius.

Although filtering by compound solubility removes many outliers, there still exists a range of ΔlogD7.4 values for functional groups. This provides insight in to the breadth of lipophilic contribution that a functional group may have in the context of forming an MMP. Such a range is partially reflective of the unique environment of substitution between two MMPs. For example, some substitutions may lead to changes in ionization state of nearby functionality, alterations in molecular conformation, masking of polarity, and minimization or maximization of dipoles. All of these outcomes can drastically impact the contribution of a given functional substitution. Notwithstanding these ranges of contribution, the size and diversity of the data set used in this analysis provide a generalized metric for the lipophilicity of standard functional groups. Importantly, as lipophilicity will always be context-dependent, a range of contributions will always exist for a given functional group; however, median measures of ΔlogD taken on a diverse array of scaffolds can provide a guide for target design.

The application of MMP analysis to Genentech’s database of compounds has allowed for the generation of a table of lipophilicity values that we anticipate will provide value to the medicinal chemistry community as a convenient reference that is based upon relevant data. As drug discovery is an iterative process where chemists often consider the impact of a marginal fragmental addition to their lead compound, easily accessible ΔlogD data for the most common substituents can allow for rapid assessment of new targets as opposed to de novo prediction of the lipophilicity of an entire molecule. In addition to lipophilicity, huge reservoirs of data are prevalent in large organizations which can provide value through the application of MMP analysis. Initiatives such as the sharing of data and trends from MMP analyses offer the advantage of being able to inform and enable the academic, pharma, and biotech sectors in a precompetitive manner,26,27 and we anticipate the completion and report of similar analyses in the near future.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hao Zheng, Timothy Heffron, Fabio Broccatelli, Michael Siu, Matthew Volgraf, and Paul Beroza for helpful discussions; Wendy Lee, Kewei Xu, and Yanzhou Liu for characterization of compounds 1–6; Eric Low and Newton Wu for performing analytical experiments; and to Genentech, Roche, and research partners thereof for generating the compounds and gathering the data upon which this analysis is built.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00489.

Characterization of compounds 1–6 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Waring M. J. Lipophilicity in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2010, 5, 235–248. 10.1517/17460441003605098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A.; Lombardo F.; Dominy B. W.; Feeney P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25. 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenlock M. C.; Austin R. P.; Barton P.; Davis A. M.; Leeson P. D. A Comparison of Physicochemical Property Profiles of Development and Marketed Oral Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 1250–1256. 10.1021/jm021053p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M. J.; Arrowsmith J.; Leach A. R.; Leeson P. D.; Mandrell S.; Owen R. M.; Pairaudeau G.; Pennie W. D.; Pickett S. D.; Wang J.; Wallace O.; Weir A. An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 475–486. 10.1038/nrd4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B.; Pease J. H. A Novel Method for High Throughput Lipophilicity Determination by Microscale Shake Flask and Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening 2013, 16, 817–825. 10.2174/1386207311301010007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T.; Iwasa J.; Hansch C. A New Substituent Constant, π, Derived from Partition Coefficients. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 5175–5180. 10.1021/ja01077a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.. Substituent Constants for Correlation Analysis in Chemistry and Biology; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.. Exploring QSAR. Fundamentals and Applications in Chemistry and Biology; ACS: WA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.; Hoekman D.. Exploring QSAR. Hydrophobic, Electronic and Steric Constants; ACS: WA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leo A.; Hansch C.; Elkins D. Partition Coefficients and Their Uses. Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 525–616. 10.1021/cr60274a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rekker R. F.; de Kort H. M. The hydrophobic fragmental constant; an extension to a 1000 data point set. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Chimica Therapeutica. 1979, 14, 479–488. [Google Scholar]

- Rekker R. F.; Mannhold R.. Calculation of Drug Lipophilicity—The Hydrophobic Fragmental Constant Approach; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mannhold R.; Poda G. I.; Ostermann C.; Tetko I. V. Calculation of Molecular Lipophilicity: State-of-the-Art and Comparison of Log P Methods on More Than 96,000 Compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 861–893. 10.1002/jps.21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnott J. A.; Planey S. L. The influence of lipophilicity in drug discovery and design. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2012, 7, 863–875. 10.1517/17460441.2012.714363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y.-C.; Rensi S. E.; Torng W.; Altman R. B. Machine learning in chemoinformatics and drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2018, 23, 1538–1546. 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalke A.; Hert J.; Kramer C. mmpdb: An Open-Source Matched Molecular Pair Platform for Large Multiproperty Data Sets. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 902–910. 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson P.; Bravi G.; Modi S.; Lowe D. ADMET rules of thumb II: A comparison of the effects of common substituents on a range of ADMET parameters. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5906–5919. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadatos G.; Alkarouri M.; Gillet V. J.; Willett P. Lead Optimization Using Matched Molecular Pairs: Inclusion of Contextual Information for Enhanced Prediction of hERG Inhibition, Solubility, and Lipophilicity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1872–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffen E.; Leach A. G.; Robb G. R.; Warner D. J. Matched Molecular Pairs as a Medicinal Chemistry Tool. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7739–7750. 10.1021/jm200452d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an MMP analysis of Pfizer lipophilicity data, see:Keefer C. E.; Chang G.; Kauffman G. W. Extraction of tacit knowledge from large ADME data sets via pairwise analysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 3739–3749. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossetter A. G.; Griffen E. J.; Leach A. G. Matched Molecular Pair Analysis in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2013, 18, 724–731. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrchan C.; Evertsson E. Matched Molecular Pair Analysis in Short: Algorithms, Applications and Limitations. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 86–90. 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patani G. A.; LaVoie E. J. Bioisosterism: A Rational Approach in Drug Design. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 3147–3176. 10.1021/cr950066q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Synopsis of Some Recent Tactical Applications of Bioisosteres in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2529–2591. 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Improving Drug Design: An Update on Recent Applications of Efficiency Metrics, Strategies for Replacing Problematic Elements, and Compounds in Nontraditional Drug Space. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 564–616. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer C.; Ting A.; Zheng H.; Hert J.; Schindler T.; Stahl M.; Robb G.; Crawford J. J.; Blaney J.; Montague S.; Leach A. G.; Dossetter A. G.; Griffen E. J. Learning Medicinal Chemistry Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) Rules from Cross-Company Matched Molecular Pairs Analysis (MMPA). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 3277–3292. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone C. Medicinal chemistry matters - a call for discipline in our discipline. Drug Discovery Today 2012, 17, 538–543. 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.