Abstract

The HDAC inhibitor 4-tert-butyl-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)phenyl)benzamide (AES-350, 51) was identified as a promising preclinical candidate for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), an aggressive malignancy with a meagre 24% 5-year survival rate. Through screening of low-molecular-weight analogues derived from the previously discovered novel HDAC inhibitor, AES-135, compound 51 demonstrated greater HDAC isoform selectivity, higher cytotoxicity in MV4-11 cells, an improved therapeutic window, and more efficient absorption through cellular and lipid membranes. Compound 51 also demonstrated improved oral bioavailability compared to SAHA in mouse models. A broad spectrum of experiments, including FACS, ELISA, and Western blotting, were performed to support our hypothesis that 51 dose-dependently triggers apoptosis in AML cells through HDAC inhibition.

Keywords: histone deacetylases, acute myeloid leukemia, enzyme inhibition, pharmacokinetics

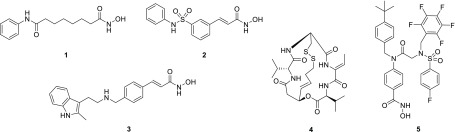

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) are two protein classes with antagonistic roles that regulate acetylation of histones as well as various cytoplasmic nonhistone proteins.1,2 HATs catalyze the transfer of acetyl groups to the ε-amino substituent of specific Lys residues, whereas classical HDACs reverse this process using a metal cofactor to catalyze hydrolysis of the acetyl group.1 There are 18 HDACs in the human proteome grouped into four classes.2 Classes I, II, and IV are metal-dependent with corresponding HDAC inhibitors typically coordinating to the metal cofactor rendering the protein inactive. Class III HDACs (sirtuins) operate in conjunction with an NAD+ cofactor and are not assessed in this study. To date, four small-molecule HDAC inhibitors have received FDA approval for cancer treatment: vorinostat (SAHA, 1),3 belinostat (PXD101, 2),4 panobinostat (LBH-589, 3),5 and romidepsin (depsipeptide-FK228, 4)6 (Figure 1). All compounds are approved specifically for hematological malignancies, although multiple clinical trials are ongoing with these compounds in combination studies against various cancers, including gliomas, solid tumors, and AML. In contrast to the FDA-approved drugs, ricolinostat and citarinostat are the first HDAC6-selective inhibitors in clinical trials.7 HDAC6 is unique among the HDACs in that it is predominantly cytosolic and facilitates microtubule deacetylation as well as regulation of PDL1 and other important targets related to cancer immunotherapy. As such, HDAC6 has been implicated in oncogenesis and metastasis, with the emergence of selective inhibitors as viable cancer therapeutics.8,9

Figure 1.

Vorinostat (1), belinostat (2), panobinostat (3), romidepsin (4), and AES-135 (5).

Recently, we reported the discovery of AES-135 (5) (Figure 1), a novel nanomolar inhibitor of HDAC3, -6, and -11 with in vitro cytotoxicity in low passage patient-derived pancreatic cancer cells, even in the presence of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs).10 Herein, we report efforts to optimize the ligand efficiency of 5 via a focused SAR analysis. Several stripped-down analogues of 5 exhibited enhanced HDAC6 inhibition and selectivity, with one inhibitor (51) also demonstrating nanomolar cytotoxicity in MV4-11 (AML) cells.

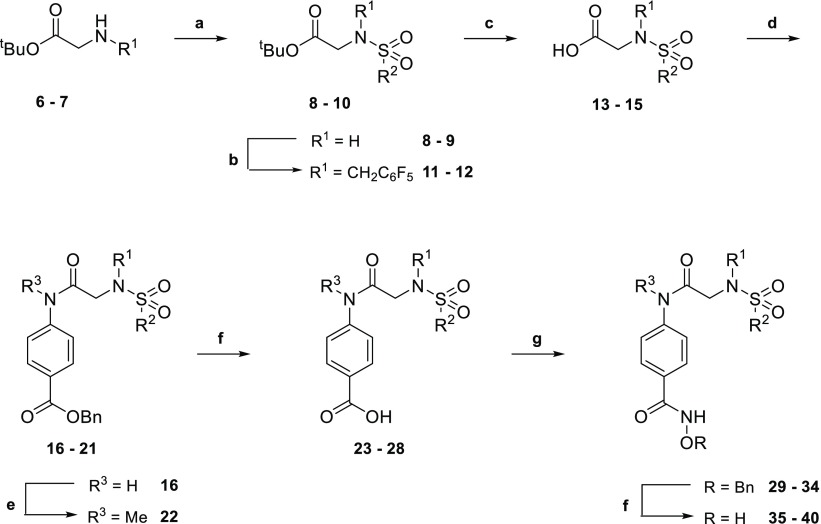

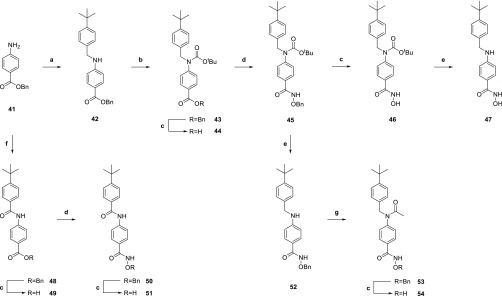

Given the molecular weight of 5 (693.7 g/mol), the relative importance of each substituent toward in vitro HDAC potency was evaluated through the synthesis of truncated analogues (35–40, 46, 47, 51, and 54). Analogues lacking one substituent were synthesized using Scheme 1. Starting from tert-butyl glycine or sarcosine hydrochloride salts (6–7), sulfonylation was followed either by acid-mediated removal of the tert-butyl protecting group or by alkylation of the sulfonamide and then tert-butyl deprotection to generate carboxylic acids 13–15. Microwave-assisted coupling with various anilines generated a series of secondary and tertiary amides. Secondary amides were alkylated prior to hydrogenation of the benzyloxy group, and tertiary amides were hydrogenated directly. The resulting carboxylic acids 23–28 were coupled with O-benzylhydroxylamine, and hydrogenation of the O-benzyl group yielded hydroxamic acids 35–40.

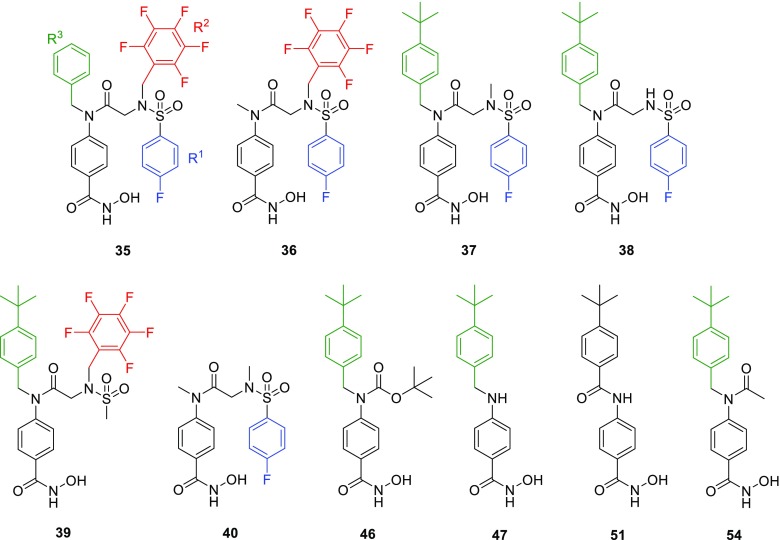

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 35–40.

Key: (a) R2SO2Cl, iPr2NEt, CH2Cl2, 16 h, rt, N2; (b) pentafluorobenzyl bromide, Cs2CO3, MeCN, 16 h, rt; (c) CF3CO2H/CHCl3 (1:3), 24 h, rt; (d) appropriate aniline, PPh3Cl2, CHCl3, 90 min, 100 °C, MW, N2; (e) MeI, Cs2CO3, MeCN, 20 h, rt; (f) H2, 10% Pd/C, THF/MeOH (2:1), 16 h, rt; (g) (i) (COCl)2, THF, DMF, 2 h, 0 °C, N2; (ii) O-benzylhydroxylamine, iPr2NEt, THF, 16 h, rt, N2. R1, R2, and R3 are variable depending on the molecule and shown below in Table 1.

Fragment derivatives of 5 lacking the sulfonamide moiety were generated using Scheme 2. Reductive amination of benzyl 4-aminobenzoate (41) with 4-tert-butylbenzaldehyde and protection of the resulting secondary aniline yielded carbamate 43. Hydrogenation of the benzyloxy group, coupling with O-benzylhydroxylamine, and removal of the O-benzyl group generated hydroxamic acid 46. Subsequent acid-mediated removal of the Boc group yielded compound 47. Deprotection of the Boc group and acylation of the aniline prior to hydrogenation of the O-benzyl group formed compound 54. Coupling of 41 with 4-tert-butylbenzoic acid, followed by conversion of the benzyl ester to the hydroxamic acid, as described previously, gave analogue 51 (AES-350).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compounds 46, 47, 51, and 54.

Key: (a) (i) 4-tert-butylbenzaldehyde, THF/TFE (4:1), 16 h, rt, (ii) NaBH4, MeOH, 6 h, rt; (b) (Boc)2O, DMAP, MeCN, 2 h, 80 °C, MW; (c) H2, 10% Pd/C, THF/MeOH (2:1), 16 h, rt; (d) (i) (COCl)2, THF, DMF, 2 h, 0 °C, N2; (ii) O-benzylhydroxylamine, iPr2NEt, THF, 16 h, rt, N2; (e) CF3CO2H/CHCl3 (1:3), 18 h, rt; (f) 4-tert-butylbenzoic acid, PPh3Cl2, CHCl3, 90 min, 100 °C, MW, N2; (g) AcCl, CH2Cl2, 24 h, 0 °C to rt.

All compounds were screened against HDAC3, -6, -8, and -11 in an enzymatic activity assay and fluorescence polarization binding assay (Table 1, Table S2, Supporting Information). Compounds 35−40, bearing a central amide and lacking one substituent relative to 5, displayed increased potency against HDAC6 (1.6−128-fold), greatly improving ligand efficiency against this protein (Table 1). Notably, when R3 was a benzyl substituent (35), general HDAC inhibition increased substantially over the larger tert-butylbenzyl (5) or smaller methyl group (36). When R1 was changed from a pentafluorobenzene (PFB) (5) to a methyl group (37) or deleted (38), potency against HDAC3 and -11 was unaffected, but there was a significant gain in HDAC8 potency. Conversion of R2 from a 4-fluorobenzene (5) to a methyl group (39) increased HDAC6 and -8 inhibition, but with a concomitant loss in HDAC11 inhibition. These results were also validated by a fluorescence polarization binding assay (Table 1).

Table 1. IC50 Values for Compounds 35–40, 46, 47, 51, and 54 against HDACs 3, 6, 8, and 11 (EMSA, n = 1) and in MV4-11, MOLM-13, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MRC-9 cells (± SD) and Ki Values against Zebra Fish HDAC6 Catalytic Domain 2.

| HDAC

activity IC50a (μM) |

HDAC6 Ki (μM) | cytotoxicity

(μM) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | HDAC3 | HDAC6 | HDAC8 | HDAC11 | HDAC6 | MV4-11 | MOLM-13 | MDA-MB-231 | MDA-MB-468 | MRC-9 |

| 1 | 0.00657 | 0.0058 | 0.497 | >1 | <0.035 | 0.310 ± 0.061c | 0.345 ± 0.035b | >25b | ||

| 5 | 0.654 | 0.190 | >1 | 0.636 | 3.600 | 1.88 ± 0.89d | 2.10 ± 0.22c | 2.62 ± 0.56c | 4.21 ± 1.76d | 19.2 ± 5.80c |

| 35 | 0.132 | 0.00149 | 0.0906 | 0.0519 | 1.860 | 5.80 ± 1.37b | 8.05 ± 1.31b | |||

| 36 | 0.213 | 0.0201 | 0.224 | >1 | 0.573 | 3.24 ± 1.14b | 14.1 ± 4.56b | >25b | >25b | >25b |

| 37 | 0.492 | 0.0552 | 0.0379 | 0.697 | 0.768 | 3.41 ± 0.29b | 5.46 ± 0.74b | >25b | >12.5b | 11.8 ± 1.46b |

| 38 | 0.372 | 0.0528 | 0.0280 | 0.665 | 0.293 | 3.33 ± 0.34b | 5.11 ± 0.88b | >12.5b | 10.8 ± 0.45b | |

| 39 | 0.213 | 0.0277 | 0.133 | >1 | 1.093 | 1.62 ± 0.29c | 2.98 ± 0.36b | >12.5b | >25b | >25b |

| 40 | 0.708 | 0.117 | 0.573 | >1 | 0.793 | 14.6 ± 1.44b | 24.8 ± 1.30b | |||

| 46 | 0.374 | 0.0282 | 0.635 | 0.837 | 0.201 | 3.12 ± 0.66b | 10.3 ± 0.95b | >25b | >25b | 9.49 ± 0.57b |

| 47 | 0.503 | 0.110 | >1 | >1 | 0.451 | 3.49 ± 1.06b | 9.47 ± 2.12b | >25b | >25b | 16.1 ± 0.34b |

| 51 | 0.187 | 0.0244 | 0.245 | >1 | 0.035 | 0.576 ± 0.131e | 6.00 ± 2.74c | >25b | >50b | 33.2 ± 10.3b |

| 54 | 0.276 | 0.0713 | 0.0854 | >1 | 0.199 | 4.24 ± 2.83b | 10.6 ± 2.17b | >25b | >25b | |

Compounds evaluated to 1 μM.

n = 2.

n = 3.

n = 4.

n = 8; R1, R2, R3 shown in blue, red, and green, respectively.

Analogues of 5 with both the PFB and 4-fluorobenzenesulfonamide substituents removed showed high variation in HDAC selectivity (Table 1). Boc-protected derivative 46 showed higher potency and selectivity for HDAC6 than 5 or its deprotected derivative 47. The structurally more rigid amide 51 was similarly potent against HDAC6 but also highly potent against HDAC3 and -8. Acetyl derivative 54 was one of the most potent HDAC8 inhibitors in this series (IC50 = 0.085 μM), with comparably high activity against HDAC6 (IC50 = 0.071 μM). None of the inhibitors lacking two aromatic substituents from compound 5 showed significant potency against HDAC11, highlighting the importance of steric bulk in the design of HDAC11-targeting compounds.

In conjunction with biochemical assays, inhibitors were assessed for cytotoxic activity in several cancer cell lines including MV4–11 and MOLM-13 (AML), MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 (breast cancer), as well as MRC-9 lung cells (noncancerous) and compared to vorinostat (1) and 5 (Table 1). Deletion of different substituents resulted in complete abrogation of cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells and reduction in potency in MOLM-13 cells (2–12 fold), with the exception of 39. In MV4–11 cells, loss of activity was smaller (2–3 fold), with 39 again demonstrating similar potency. While 35 showed impressive HDAC6 selectivity and potency in the enzymatic assay, potency in MV4–11 cells was markedly weaker (>5 μM). In contrast, 51 was more potent than 5, with submicromolar activity (IC50 = 0.58 ± 0.13 μM) akin to that of vorinostat (IC50 = 0.31 ± 0.061 μM). At < 50% the molecular weight of 5, compound 51 is more ligand efficient and exemplifies a large therapeutic index (IC50 > 30 μM in noncancerous MRC-9 cells). Compound 51 was also shown to be effective in AML-3 (acute myeloid leukemia) cells (IC50 = 0.73 ± 0.12 μM) similar to SAHA (IC50 = 1.30 ± 0.85 μM) and citarinostat (IC50 = 4.40 ± 0.99 μM). In combination with the observed in vitro potency and selectivity of 51 (HDAC6 IC50 = 24 nM), it was selected for further pharmacologic studies.

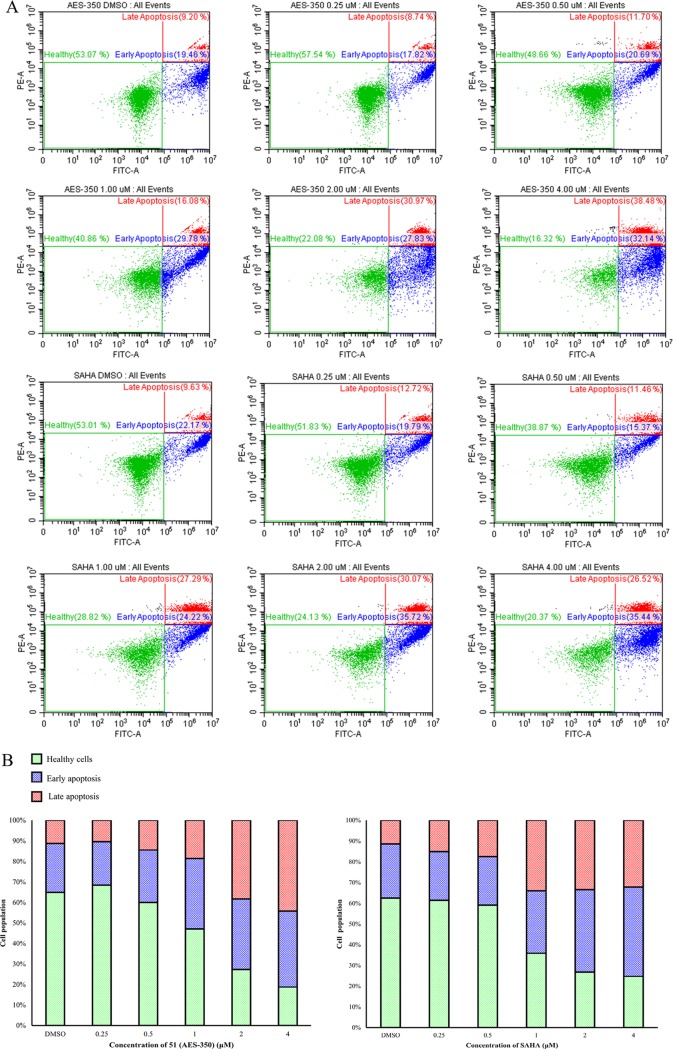

The cytotoxicity data for 51 was corroborated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Figure 2). MV4–11 cells were cultured for 18 h with increasing concentrations of 51 or SAHA before treatment with apoptosis indicators annexin V and propidium iodide. The findings revealed a clear dose-dependent increase in the percentage of cells entering late-stage apoptosis, similar to SAHA, further supporting the anticancer activity of 51 in this cell line. In vitro stability of 51 was evaluated in mouse hepatocytes by comparing the rates of intrinsic clearance of verapamil (control) with 51. Compound 51 (t1/2 = 28.3 min) exhibited ∼1.5-fold longer half-life than verapamil (t1/2 = 18.0 min). Previous assays under the same conditions revealed a longer half-life for 5 (t1/2 = 38.5 min), although verapamil also showed a 17.8% variation (t1/2 = 21.9 min).10 Normalizing the data of 5 and 51 according to the control verapamil suggests that after removing >50% of the total mass of 5 the hepatocyte half-life of 51 was reduced by only 10%. Similarly, the clearance rate of 51 (49.1 μL/min per 106 cells) was lower than that of verapamil (77.0 μL/min per 106 cells) but faster than that of 5 (36.0 μL/min per 106 cells) (Table S5 and Figures S12–S15, Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

(A) Dot plots and (B) stacked bar graphs representing the distribution of MV4-11 cells classed as healthy, early apoptosis, and late apoptosis 18 h postdosing with varying concentrations of SAHA and 51 (AES-350) using FACS.

Notably, 51 was markedly less bound to plasma proteins (95.3% protein bound) compared to 5 (99.6%), although both compounds were poorly recovered (∼20%), suggesting a metabolic liability in their composition (Tables S6–S8, Supporting Information).10

The significantly lower molecular weight of 51 (312.4 g/mol) suggested it would exhibit superior membrane permeability in comparison to 5. Parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) was used to approximate permeation of 51 through the blood–brain barrier, where a permeability coefficient (−Log Pe) < 6 is defined as having high permeability. Compound 51 was found to have a −Log Pe of 5.14, indicating relatively good lipid bilayer permeability, and was 87.1% recovered in comparison to the parent 5 (−Log Pe = 7.73, 28.7% recovery, Tables S9–S12, Supporting Information). Compound 51 was further analyzed in a small intestinal membrane model (Caco-2) assay to gauge permeability through a monolayer of epithelial cells as well as compound efflux. Metoprolol and digoxin were used as controls with low and high efflux ratios, respectively. In agreement with PAMPA, 51 demonstrated a high permeability (apparent permeability coefficient, Papp A–B = 3.45 × 10–6 cm/s), approximately 13-times the rate of 5 (Papp A–B = 0.27 × 10–6 cm/s). Additionally, efflux ratios for metoprolol, digoxin, and 5 were all higher (1.00, 72.99 and 3.83, respectively) in comparison to 51 (0.64) indicating that 51 would likely demonstrate intestinal absorption if ingested orally (Tables S13–S17, Supporting Information).11

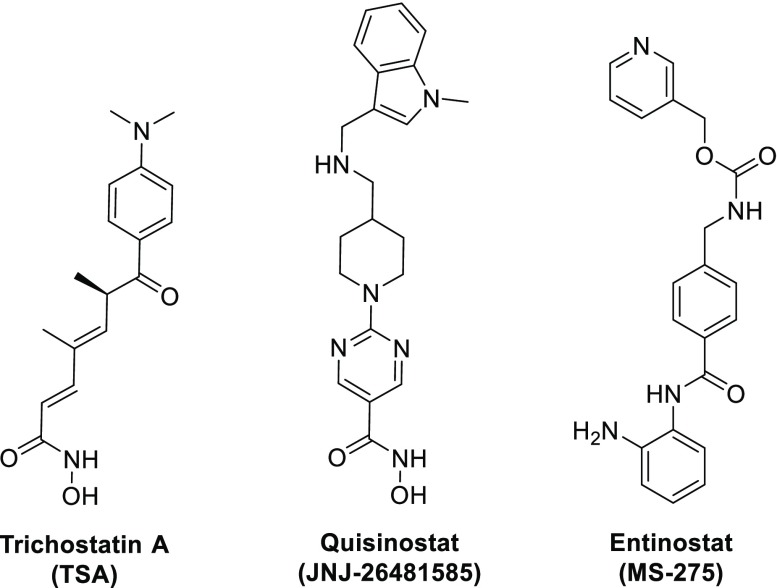

To gain a comprehensive HDAC selectivity profile of 51, the compound was screened in vitro against all 11 metal-dependent HDACs (Table 2). Known pan-HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A (TSA), quisinostat (JNJ-26481585, Phase II clinical trials in CTCL and ovarian cancer), and Group I selective inhibitor entinostat (MS-275, Phase III clinical trials in breast cancer/Phase II trials in renal cell carcinoma) were used as positive controls and showed IC50 values/selectivity profiles consistent with the literature.12−14 Compound 51 was found to be selective for HDAC6 with minimal inhibition observed for the remaining HDACs, in contrast to both quisinostat and entinostat which displayed low nanomolar IC50 values against almost all HDACs (Tables S2–S4 and Figures S1–S11, Supporting Information). Indeed, 51 could be considered equally to marginally more selective for HDAC6 than ricolinostat and citarinostat under these assay conditions. Although both compounds are more potent than 51 against HDAC6, they are also more potent against HDAC3, which reduces their selectivity.

Table 2. IC50 Values for 51 against 11 Classical HDACs (EMSA, n = 1).

| HDAC

IC50 (μM) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 51 | 0.605 | >1 | 0.187 | >1 | >1 | 0.0244 | >1 | 0.245 | >1 | 0.899 | >1 |

| TSA | 0.000681 | 0.00274 | 0.000404 | >1 | 0.776 | 0.000954 | 0.482 | 0.207 | >1 | 0.00161 | >1 |

| JNJ-26481585 | 0.000617 | 0.00216 | 0.000478 | 0.00461 | 0.00595 | 0.0399 | 0.00404 | 0.0024 | 0.0067 | 0.00196 | >1 |

| MS-275 | 0.118 | 0.247 | 0.223 | >1 | >1 | >1 | >1 | >1 | >1 | >1 | >1 |

| ricolinostat | 0.379 | 0.0143 | >1 | 0.00259 | 0.245 | >1 | |||||

| citarinostat | 0.318 | 0.0125 | >1 | 0.00221 | 0.171 | >1 | |||||

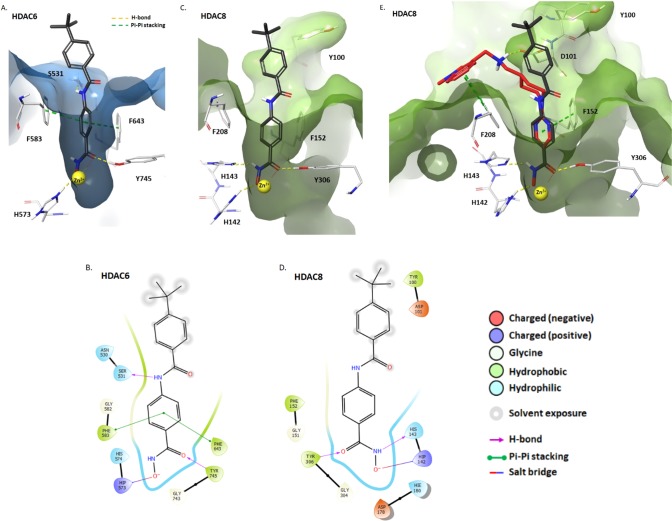

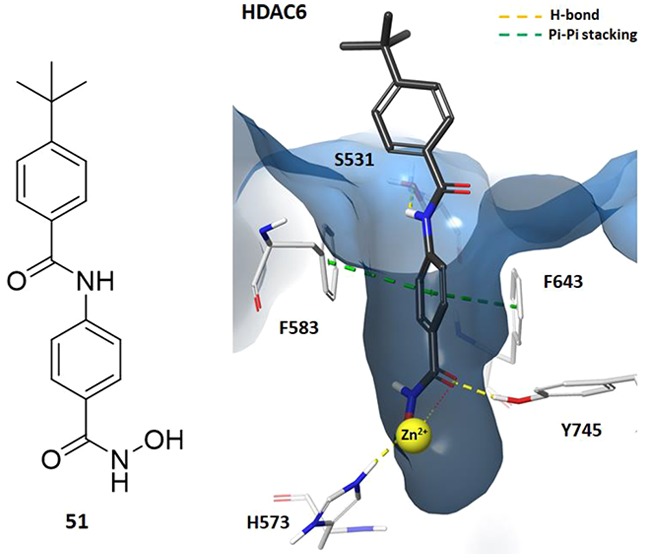

To explain the observed selectivity of 51, the compound was modeled in catalytic domain 2 (CD2) of HDAC6 and HDAC8 using Maestro v11.9.01 (Schrödinger, LLC)15−17 (Figure 3A–D). The hydroxamic acid of 51 formed a H-bond between the carbonyl oxygen and hydroxyl group of Tyr745 (HDAC6) or Tyr306 (HDAC8) and a salt bridge interaction between the deprotonated acid and protonated His573 (HDAC6) or His142 (HDAC8). Crucially, the benzene ring of 51 formed π-stacking interactions with Phe583 and Phe643 of HDAC6 that were not observed in HDAC8. Additionally, the amide NH in 51 formed a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl of Ser531, giving an average free energy of binding (ΔGB) of −8.5 kcal/mol. These interactions are believed to be responsible for the selectivity of this structural motif for HDAC6 over other isoforms.18,19 Neither of these interactions were observed with HDAC8 (ΔGB was −7.8 kcal/mol, Figure S16, Supporting Information). The rigid conformation of 51 means that the tert-butylbenzene ring cannot avoid nearby residues, such as Y100 (HDAC8), potentially causing steric clashes that more flexible compounds, such as Quisinostat, can avoid (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

(A) Docking of 51 with zebra fish HDAC6 CD2 (light blue) (PDB: 6CSR). (B) Ligand interaction diagram depicting the key interactions of 51 in HDAC6 CD2. (C) Docking of 51 in the human HDAC8 catalytic domain (green) (PDB: 6HSK). (D) Ligand interaction diagram depicting the key interactions of 51 in the HDAC8 catalytic domain. (E) Overlap of 51 (gray) with quisinostat (red) in the human HDAC8 catalytic domain (PDB: 6HSK). In A, C, and E, 51 is illustrated by gray (C), white (H), blue (N), red (O), and yellow (Zn2+). Other interactions are shown as follows: π-stacking (green dashed lines), H-bonds and salt bridges (yellow dashed lines), and Zn2+ chelation (yellow/red dots).

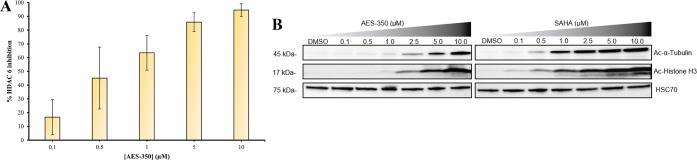

To validate the proposed cellular HDAC inhibition, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent-based assay (ELISA) was performed using HeLa cervical cancer cell lysates. HeLa cells highly express HDAC6 and were sensitive to 51 (IC50 = 2.53 ± 0.57 μM) (Table S1, Supporting Information). Correspondingly, ELISA assays depicted a dose-dependent increase in HDAC6 inhibition (IC50 = 0.58 ± 0.13 μM) and supported 51-induced cell death via HDAC6 inhibition (Figure 4A). ELISA-based data were also supported by Western blot analysis of 51-treated MV4–11 cells (Figure 4B) with an observed dose-dependent increase in acetylated α-tubulin (Ac-α-tubulin), a substrate of HDAC6.20 Collectively, ELISA and Western blot analysis suggest 51 elicits HDAC6 inhibition in vitro to dose-dependently facilitate apoptosis. It is important to note that despite the observed HDAC6 selectivity in vitro there is also a significant reduction of the biomarker of acetylated histone (Ac-Histone H3, an indication of pan-HDAC activity)21 and acetylated tubulin in cellulo which suggests there may be additional Class I inhibitory activity of the compound.9 As such, the in vitro selectivity of 51 may not be observed in cellulo to the same extent which may be the result of alternative inhibition mechanisms.

Figure 4.

(A) HDAC6 inhibition profile with varying concentrations of 51 in HeLa cell lysates (IC50 = 0.58 ± 0.13 μM, n = 2). (B) Western blots probing for Ac-α-tubulin, Ac-Histone H3, and HSC70 from MV4–11 after 6 h with varying concentrations of 51 (AES-350) and SAHA.

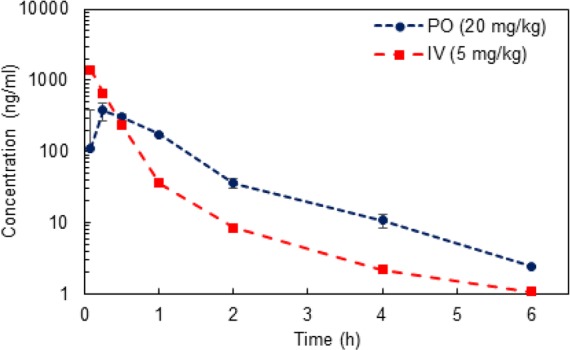

To evaluate pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of 51, CD-1 mice were dosed (20 mg/kg, PO, and 5 mg/kg IV; Figure 5 and Tables S18–S22, Supporting Information). The single dose oral bioavailability (F) of 51 was 19.8%. In comparison, the reported F value for SAHA in mice is significantly lower (8%).22 The rapid clearance rate of 51 (av. t1/2 = 0.853 min.) would require regular dosing, alternative administration routes, or larger dosages. In previous studies, 5 achieved an average Cmax of 10.74 μM in NSG mice that was sustained for 8 h (t1/2 = 5.0 h).10 However, it should be noted that 5 could only be dosed by IP due to poor absorption profiles.

Figure 5.

Mean plasma concentrations of 51 in CD-1 mice following PO (20 mg/kg, n = 3) and IV administration (5 mg/kg, n = 3).

Systematic modifications of novel HDAC inhibitor, 5, led to the discovery of 51, a comparatively ligand-efficient compound. Encouragingly, 51 exhibited an in vitro HDAC6 selectivity profile comparable to that of ricolinostat and citarinostat. This translated into cellular target engagement, with dose-dependent HDAC6 inhibition in HeLa and MV4–11 cells. Although 51 did not display the same extent of HDAC6 selectivity in cellulo as observed in the in vitro studies, the compound demonstrated superior cytotoxicity compared to its predecessor in MV4–11 cells, which was corroborated with FACS experiments. The membrane permeability of 51 was also significantly improved compared to 5 based on PAMPA and Caco-2 assays, which translated into an orally absorbed therapeutic in CD-1 mice. While initial pharmacological data have been promising, ultimately, 51 was not as potent as its FDA-approved competitor SAHA in AML cells. Moreover, although 51 was discovered during our SAR studies, we subsequently discovered it had been previously documented in patent literature.23−25 Despite these shortcomings, this investigation represents the first disclosure of the mechanism of action for 51 in cancer cells with potency in AML, potentially enabling close analogues to reach preclinical investigation for AML treatment. Overall, 51 represents an improved orally bioavailable analogue of 5 and is a promising candidate for further medicinal chemistry efforts to build upon the HDAC selectivity/potency and pharmacological properties.

Acknowledgments

P.T.G. is supported by research grants from NSERC (RGPIN-2014-05767), CIHR (MOP-130424, MOP-137036), Canada Research Chair (950-232042), Canadian Cancer Society (703963), Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation (705456), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of Canada and infrastructure grants from CFI (33536), and the Ontario Research Fund (34876). A.E.S. is supported by a Mitacs Accelerate Grant (IT05960).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- SAHA

suberanilohydroxamic acid

- CTCL

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- PTCL

peripheral T-cell lymphoma

- MM

multiple myeloma

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- CAF

cancer-associated fibroblast

- IP

intraperitoneal

- PO

per os

- Boc

tert-butoxycarbonyl

- PFB

pentafluorobenzyl

- FB

fluorobenzene

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- PAMPA

parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- TSA

trichostatin A

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00471.

Author Contributions

† A.E.S. and J.M.G. contributed equally to this work. A.E.S., J.M.G., L.H., A.E.J., and A.D.C. synthesized/characterized the compounds. J.M.G., N.N., D.S., S.B., P.M., O.O.O., E.D.A., and A.S. carried out biological and biophysical evaluation of the compounds. Y.S.R. performed in silico experiments. A.E.S., J.M.G., E.D.A., and P.T.G. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Khan O.; La Thangue N. B. HDAC Inhibitors in Cancer Biology: Emerging Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 85–94. 10.1038/icb.2011.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccacci E.; Minucci S. Inhibition of Histone Deacetylases in Cancer Therapy: Lessons from Leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114 (6), 605–611. 10.1038/bjc.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai T.; Wakimoto N.; Yin D.; Gery S.; Kawamata N.; Takai N.; Komatsu N.; Chumakov A.; Imai Y.; Koeffler H. P. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid (Vorinostat, SAHA) Profoundly Inhibits the Growth of Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121 (3), 656–665. 10.1002/ijc.22558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X.; Ara G.; Mills E.; LaRochelle W. J.; Lichenstein H. S.; Jeffers M. Activity of the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Belinostat (PXD101) in Preclinical Models of Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122 (6), 1400–1410. 10.1002/ijc.23243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis L.; Pan Y.; Smyth G. K.; George D. J.; McCormack C.; Williams-Truax R.; Mita M.; Beck J.; Burris H.; Ryan G.; et al. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Panobinostat Induces Clinical Responses with Associated Alterations in Gene Expression Profiles in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14 (14), 4500–4510. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekarz R. L.; Frye R.; Turner M.; Wright J. J.; Allen S. L.; Kirschbaum M. H.; Zain J.; Prince H. M.; Leonard J. P.; Geskin L. J.; et al. Phase II Multi-Institutional Trial of the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Romidepsin as Monotherapy for Patients with Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27 (32), 5410–5417. 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasmahapatra G.; Patel H.; Friedberg J.; Quayle S. N.; Jones S. S.; Grant S. In Vitro and in Vivo Interactions between the HDAC6 Inhibitor Ricolinostat (ACY1215) and the Irreversible Proteasome Inhibitor Carfilzomib in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13 (12), 2886–2897. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Li T.; Zhang C.; Hassan S.; Liu X.; Song F.; Chen K.; Zhang W.; Yang J. Histone Deacetylase 6 in Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 10.1186/s13045-018-0654-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl D. T.; Raje N.; Jagannath S.; Richardson P.; Hari P.; Orlowski R.; Supko J. G.; Tamang D.; Yang M.; Jones S. S.; et al. Ricolinostat, the First Selective Histone Deacetylase 6 Inhibitor, in Combination with Bortezomib and Dexamethasone for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23 (13), 3307–3315. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shouksmith A. E.; Shah F.; Grimard M. L.; Gawel J. M.; Raouf Y. S.; Geletu M.; Berger-Becvar A.; De Araujo E. D.; Luchman H. A.; Heaton W. L.; et al. Identification and Characterization of AES-135, a Hydroxamic Acid-Based HDAC Inhibitor That Prolongs Survival in an Orthotopic Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (5), 2651–2665. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambuy Y.; De Angelis I.; Ranaldi G.; Scarino M. L.; Stammati A.; Zucco F. The Caco-2 Cell Line as a Model of the Intestinal Barrier: Influence of Cell and Culture-Related Factors on Caco-2 Cell Functional Characteristics. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2005, 21, 1–26. 10.1007/s10565-005-0085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W. G.; Wei Y.; Stevenson W.; Kuang S. Q.; Fang Z.; Zhang M.; Arts J.; Garcia-Manero G. Preclinical Antileukemia Activity of JNJ-26481585, a Potent Second-Generation Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor. Leuk. Res. 2010, 34 (2), 221–228. 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts J.; King P.; Mariën A.; Floren W.; Beliën A.; Janssen L.; Pilatte I.; Roux B.; Decrane L.; Gilissen R.; et al. JNJ-26481585, a Novel “Second-Generation” Oral Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, Shows Broad-Spectrum Preclinical Antitumoral Activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15 (22), 6841–6851. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatamiya T.; Saito A.; Sugawara T.; Nakanichi O. Isozyme-Selective Activity of the HDAC. Proc. Amer Assoc Cancer Res. 2004, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A.; Murphy R. B.; Repasky M. P.; Frye L. L.; Greenwood J. R.; Halgren T. A.; Sanschagrin P. C.; Mainz D. T. Extra Precision Glide: Docking and Scoring Incorporating a Model of Hydrophobic Enclosure for Protein-Ligand Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49 (21), 6177–6196. 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren T. A.; Murphy R. B.; Friesner R. A.; Beard H. S.; Frye L. L.; Pollard W. T.; Banks J. L. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 2. Enrichment Factors in Database Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47 (7), 1750–1759. 10.1021/jm030644s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A.; Banks J. L.; Murphy R. B.; Halgren T. A.; Klicic J. J.; Mainz D. T.; Repasky M. P.; Knoll E. H.; Shelley M.; Perry J. K.; et al. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47 (7), 1739–1749. 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter N. J.; Mahendran A.; Breslow R.; Christianson D. W. Unusual Zinc-Binding Mode of HDAC6-Selective Hydroxamate Inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114 (51), 13459–13464. 10.1073/pnas.1718823114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter N. J.; Wagner F. F.; Christianson D. W. Entropy as a Driver of Selectivity for Inhibitor Binding to Histone Deacetylase 6. Biochemistry 2018, 57 (26), 3916–3924. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbert C.; Guardiola A.; Shao R.; Kawaguchi Y.; Ito A.; Nixon A.; Yoshida M.; Wang X. F.; Yao T. P. HDAC6 Is a Microtubule-Associated Deacetylase. Nature 2002, 417 (6887), 455–458. 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto E.; Yoshida M. Erasers of Histone Acetylation: The Histone Deacetylase Enzymes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6 (4), a018713. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh P. R.; Goh E.; Zeng P.; New L. S.; Xin L.; Pasha M. K.; Sangthongpitag K.; Yeo P.; Kantharaj E. Vitro Phase I Cytochrome P450 Metabolism, Permeability and Pharmacokinetics of SB639, a Novel Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor in Preclinical Species. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30 (5), 1021–1024. 10.1248/bpb.30.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho H. S.; Baek H. S.; Lee J. A.; Park C. M.; Kim D. H.; Chang I. S.; Lee O. S.. Hydroxamic Acid Derivatives and the Preparation Method Thereof, WO2005/19162 A1, 2009.

- Lu Q.; Yang Y. T.; Chen C. S.; Davis M.; Byrd J. C.; Etherton M. R.; Umar A.; Chen C. S. Zn2+-Chelating Motif-Tethered Short-Chain Fatty Acids as a Novel Class of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 467. 10.1021/jm0303655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London C. A.; Lin T.-Y.; Kulp S.. Methods and Compositions for Inhibiting and Preventing the Growth of Malignant Mast Cells. WO2011/103563 A1, 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.