Abstract

Background

Previous systematic reviews have not shown clear benefit of glucocorticoids for acute viral bronchiolitis, but their use remains considerable. Recent large trials add substantially to current evidence and suggest novel glucocorticoid‐including treatment approaches.

Objectives

To review the efficacy and safety of systemic and inhaled glucocorticoids in children with acute viral bronchiolitis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2012, Issue 12), MEDLINE (1950 to January week 2, 2013), EMBASE (1980 to January 2013), LILACS (1982 to January 2013), Scopus® (1823 to January 2013) and IRAN MedEx (1998 to November 2009).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing short‐term systemic or inhaled glucocorticoids versus placebo or another intervention in children under 24 months with acute bronchiolitis (first episode with wheezing). Our primary outcomes were: admissions by days 1 and 7 for outpatient studies; and length of stay (LOS) for inpatient studies. Secondary outcomes included clinical severity parameters, healthcare use, pulmonary function, symptoms, quality of life and harms.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data on study and participant characteristics, interventions and outcomes. We assessed risk of bias and graded strength of evidence. We meta‐analysed inpatient and outpatient results separately using random‐effects models. We pre‐specified subgroup analyses, including the combined use of bronchodilators used in a protocol.

Main results

We included 17 trials (2596 participants); three had low overall risk of bias. Baseline severity, glucocorticoid schemes, comparators and outcomes were heterogeneous. Glucocorticoids did not significantly reduce outpatient admissions by days 1 and 7 when compared to placebo (pooled risk ratios (RRs) 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.08 and 0.86; 95% CI 0.7 to 1.06, respectively). There was no benefit in LOS for inpatients (mean difference ‐0.18 days; 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.04). Unadjusted results from a large factorial low risk of bias RCT found combined high‐dose systemic dexamethasone and inhaled epinephrine reduced admissions by day 7 (baseline risk of admission 26%; RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.95; number needed to treat 11; 95% CI 7 to 76), with no differences in short‐term adverse effects. No other comparisons showed relevant differences in primary outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Current evidence does not support a clinically relevant effect of systemic or inhaled glucocorticoids on admissions or length of hospitalisation. Combined dexamethasone and epinephrine may reduce outpatient admissions, but results are exploratory and safety data limited. Future research should further assess the efficacy, harms and applicability of combined therapy.

Plain language summary

Glucocorticoids for acute viral bronchiolitis in infants and young children under two years of age

Bronchiolitis is the most common acute infection of the airways and lungs during the first years of life. It is caused by viruses, the most common being respiratory syncytial virus. The illness starts similar to a cold, with symptoms such as a runny nose, mild fever and cough. It later leads to fast, troubled and often noisy breathing (for example, wheezing). While the disease is often mild for most healthy babies and young children, it is a major cause of clinical illness and financial health burden worldwide. Hospitalisations have risen in high‐income countries, there is substantial healthcare use and bronchiolitis may be linked with preschool wheezing disorders and the child later developing asthma.

There is variation in how physicians manage bronchiolitis, reflecting the absence of clear scientific evidence for any treatment approach. Anti‐inflammatory drugs like glucocorticoids (for example, prednisolone or dexamethasone) have been used based on apparent similarities between bronchiolitis and asthma. However, no clear benefit of their use has been shown.

Our systematic review found 17 controlled studies involving 2596 affected children that used these drugs for a short duration and assessed short‐term outcomes. When comparing glucocorticoids to placebo, no differences were found for either hospital admissions or length of hospital stay. There was no substantial benefit in other health outcomes. These findings are consistent and likely to be applicable in diverse settings.

Exploratory results from one large high‐quality trial suggest that combined treatment of systemic glucocorticoids (dexamethasone) and bronchodilators (epinephrine) may significantly reduce hospital admissions. There were no relevant short‐term adverse effects that were any different from those seen with an inactive placebo, while long‐term safety was not assessed. Further research is needed to confirm the efficacy, safety and applicability of this promising approach.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Acute viral bronchiolitis is the most common acute infection of the lower respiratory tract during the first year of life (Wright 1989). It is diagnosed clinically in infants and young children, based on a history of rhinorrhoea and low‐grade fever that progress to cough and respiratory distress, with findings of tachypnoea, chest retractions and wheeze, crackles, or both, on examination (Bush 2007; Smyth 2006; Taussig 2008). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is responsible for the majority of cases, usually in seasonal epidemics (Smyth 2006; Yusuf 2007). Other viral agents, particularly rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, bocavirus and adenovirus, may also be involved as single or dual infections (Calvo 2010; Kusel 2006; Mansbach 2008b; Mansbach 2012). Although bronchiolitis is usually a straightforward diagnosis, some variability in its definition exists. This may be due to poor agreement on the identification of early childhood wheezing phenotypes and worldwide differences in disease semantics (Brand 2008; Everard 2009; Mansbach 2008a).

Bronchiolitis is a major cause of clinical morbidity and its financial health burden is substantial. Population‐based studies in developed countries suggest an incidence ratio of approximately 10% within the first year of life, with hospital admissions up to 3% (Koehoorn 2008; Mansbach 2005; Shay 1999; Wright 1989). While mortality is rare, hospitalisations have increased steadily in North America and Europe over the past 10 to 20 years (Langley 2003; Shay 1999; van Woensel 2002), with rising inpatient health care costs (Langley 1997; Paramore 2004; Pelletier 2006). Additionally, a majority of cases with mild illness cared for in the community are responsible for a considerable number of outpatient visits, loss of parental work time and decreased quality of life (Carroll 2008; Mansbach 2007; Robbins 2006). RSV infection, including bronchiolitis, is a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality at a global level (Nair 2010).

Bronchiolitis involves acute inflammation of the bronchiolar airways initiated by viral infection, regardless of the causative agent. Airway oedema, necrosis and mucous plugging are the hallmark pathological features, and air flow obstruction ensues (Taussig 2008). Factors underlying disease severity are only partially understood, but clinical determinants include lower age, prematurity, chronic lung, heart or neurological disease, immunodeficiency and ethnicity (Damore 2008; Figueras‐Aloy 2008; Meissner 2003; Simoes 2003; Simoes 2008). There is likely a complex interplay between host (i.e. genetic markers), agent (i.e. viral loads, specific agents and co‐infections) and environmental factors (i.e. crowding, tobacco smoke exposure) (Colosia 2012; Collins 2008; DiFranza 2012; Mansbach 2012; Miyairi 2008;Papadopoulos 2002). Basic, translational and clinical research studies are elucidating the association between bronchiolitis, preschool wheezing disorders and later asthma (Martinez 2005; Perez‐Yarza 2007; Singh 2007; Sly 2010).

Description of the intervention

The current treatment for bronchiolitis is controversial. There is substantial variation in its management throughout the world, reflecting the absence of clear evidence for any single treatment approach (Babl 2008; Barben 2003; Brand 2000; Gonzalez 2010; Mansbach 2005; Plint 2004). Many interventions failed to show consistent and relevant effects (Bialy 2011). Recently, both nebulised epinephrine and hypertonic saline have emerged as options for improving relevant outcomes in outpatient and inpatient populations, respectively (Hartling 2011a; Zhang 2011). However, no routine treatment is yet recommended by most evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines worldwide (AAP 2006; Baumer 2007; Turner 2008).

The case of glucocorticoids highlights the uncertainties of research in this field. Trials assessing their use date back to the 1960s, with different potencies, modes of administration, dosages and regimens of these drugs having been recommended (Connolly 1969; Leer 1969). However, results from randomised clinical trials (RCTs) have been heterogeneous, leading to ongoing controversy regarding their use. Differences in participants, care settings and outcomes may account for these conflicting results, and have led to distinct interpretations (Everard 2009; Guilbert 2011; Hall 2007; Weinberger 2003; Weinberger 2007).

How the intervention might work

Glucocorticoid use in bronchiolitis was originally thought to have equivalent benefits to those in acute asthma. Similarities between clinical findings were expected to express equivalent biological and physiological mechanisms attributable to inflammation (Leer 1969). However, evidence suggests there is heterogeneity in inflammatory pathways and mediators activated in different wheezing phenotypes which may underlie bronchiolitis (for example, neutrophil‐ versus eosinophil‐mediated inflammation) (Halfhide 2008). Mechanistic studies have shown that glucocorticoids have limited anti‐inflammatory effects in this condition (Buckingham 2002; Somers 2009) and there is an ongoing debate regarding their efficacy in acute virus‐induced wheezing in preschool children (Bush 2009; Ducharme 2009; Panickar 2009). Further, potential benefits need to be considered in light of possible short‐ and long‐term adverse effects of glucocorticoid use. While the interactive effect of bronchodilators and glucocorticoids has been widely known in asthma, both at a clinical and biological level, its use as a putative treatment option in bronchiolitis has only been explored recently (Plint 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

While guideline implementation has changed prescription patterns, glucocorticoids are still widely used (Barben 2000; Barben 2008; David 2010). The latest version of this review integrated critical results from the two largest multi‐centre studies in this area (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009) and examined the use of combined therapy with bronchodilators or adrenaline. We continue to update the current body of evidence in order to adequately assess the efficacy and safety of glucocorticoids in bronchiolitis.

Objectives

To review the efficacy and safety of systemic and inhaled glucocorticoids in children with acute viral bronchiolitis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs irrespective of risk of bias, sample size, publication status or language of publication.

Types of participants

Studies should include infants and young children ≤ 24 months of age with acute viral bronchiolitis. Bronchiolitis was defined clinically as a first episode of acute wheezing, respiratory distress and clinical evidence of a viral infection (cough, coryza, fever). Many bronchiolitis trial reports do not specify clinical findings required for participant inclusion (King 2004); we included all studies if other diagnoses (for example, pneumonia) could be excluded. We did not restrict inclusion based on specific findings on examination (for example, crackles) or viral aetiology.

We excluded studies in which any participant had a history of wheezing or respiratory distress (one or more previous episodes), a formal diagnosis of asthma, or if reporting of these items was unclear. We focused on first time wheezing so results could be directly pertinent to infants with 'typical' viral bronchiolitis, as opposed to children with acute recurrent wheezing. We did not exclude trials based on other reported participant characteristics, including gestational age and co‐morbidities.

We included studies of both inpatients and outpatients (ambulatory care and/or emergency department), and excluded trials in the intensive care setting or with intubated and/or ventilated participants.

Types of interventions

The interventions of interest were short‐term systemic or inhaled glucocorticoids administered for the acute care of bronchiolitis. We considered all types of glucocorticoids, dosages, durations and routes of administration. Glucocorticoids could be administered alone or combined with co‐interventions (for example, bronchodilators), used with or without a fixed protocol. We excluded trials assessing the use of longer courses of glucocorticoids started during the acute phase for the prevention of post‐bronchiolitic wheezing.

Comparators included either placebo or another intervention (for example, bronchodilators, other glucocorticoid). Inhaled isotonic saline is frequently used as a placebo control for inhaled drugs. We excluded studies comparing different doses or regimens of the same glucocorticoid.

Types of outcome measures

We selected primary outcomes based a priori on clinical relevance and patient importance; secondary outcomes assessed other relevant health domains (clinical severity, pulmonary function, healthcare use, patient/parent‐reported symptoms and status, and harms). We included studies if they reported numeric data on at least one primary or secondary outcomes assessed within the first month after acute bronchiolitis. We considered different timings of outcome assessment, based on a priori relevance and available data.

Primary outcomes

Rate of admission by days one and seven for outpatient studies.

Length of stay (LOS) for inpatient studies.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical severity scores.

O2 saturation, respiratory rate and heart rate.

Hospital re‐admissions (for inpatient studies) and return healthcare visits (for all studies); LOS (for outpatient studies).

Pulmonary function tests.

Symptoms and quality of life.

Short‐ and long‐term adverse events.

We selected the following time points and intervals for clinical scores, O2 saturation, respiratory and heart rate: 60 and 120 minutes, three to six hours, six to 12 hours, 12 to 24 hours, 24 to 72 hours, and three to 10 days. The time points selected for re‐admissions and return visits were days 1 to 10, and 11 to 30. We also considered data on all other reported outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

The previous version of this review used an inclusive search strategy as part of a comprehensive systematic review evaluating the effect of three types of interventions in bronchiolitis (glucocorticoids, epinephrine and other bronchodilators) (Hartling 2011b).

Electronic searches

Previously we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 4), which contains the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Specialised Register, MEDLINE (1950 to November Week 2, 2009), EMBASE (1980 to Week 47, 2009), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information) (1982 to 25 November 2009), Scopus® (1823 to 25 November 2009) and IRAN MedEx (1998 to 26 November 2009).

We developed search strings by scanning search strategies of relevant systematic reviews and examining index terms of potentially relevant studies. We applied and modified a validated RCT filter according to each database (Glanville 2006). We applied no publication or language restrictions. The search strings for each database can be found in Appendix 1 to Appendix 6.

For this 2013 update we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2012, Issue 12, part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 21 January 2013), which contains the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Specialised Register, MEDLINE (October 2009 to January week 2, 2013), EMBASE (November 2009 to January 2013), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information) (2009 to January 2013) and Scopus (2009 to January 2013) (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

To identify unpublished studies and studies in progress we searched the following clinical trials registers on 1 August 2012: ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP Search Portal – World Health Organization. We searched the following conference proceedings: Pediatric Academic Societies (2003 to 2012), European Respiratory Society (2003 to 2011), American Thoracic Society (2006 to 2012).

We identified additional published, unpublished or ongoing studies by handsearching reference lists and included or excluded studies of relevant reviews. In addition, we contacted topic specialists.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Five review authors (AP, LB, LH, NH or RF) independently screened the titles, keywords and abstracts (when available) to determine if an article met the inclusion criteria. These review authors independently assessed the full text of all articles classified as 'include' or unclear' using a standardised form. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by an arbitrator (AP, TK, DJ, or RF).

Data extraction and management

We extracted data using a standardised form in paper or electronic format (available from authors). Seven review authors extracted data (LB, LH, AM, HM, RF, OT or JF) and three review authors (LB, AM or RF) independently checked for accuracy and completeness. We resolved discrepancies by consensus or in consultation with a third review author (TK, AP or DJ). A statistician (BV) checked all quantitative data during analysis. Extracted data included study characteristics, funding, inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, interventions, outcomes and results.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool, which includes seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias (Higgins 2011). We assessed blinding and incomplete outcome data separately for the following groups of outcomes: healthcare use (rate of admission, LOS, hospital re‐admissions and return healthcare visits); clinical parameters (clinical severity scores, O2 saturation, respiratory rate and heart rate); pulmonary function; patient/parent‐reported outcomes (symptoms and quality of life measures) and other outcomes such as adverse events. Where trial protocols or trial registers were unavailable, we assessed selective outcome reporting by comparing outcomes reported in the methods and results sections. We summarised risk of bias for each study across outcomes based on individual domain assessments ('high' if one or more domains were high; 'low' if all domains were low; 'unclear' for all other studies).

Three review authors (LB, LH or RF) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies; we resolved discrepancies by consensus. One review author (OT) assessed study reports written in Turkish. We pilot tested the risk of bias tool on a sample of five studies and used the results to adapt decision rules (available from authors).

Grading the body of evidence

We used the Evidence‐Based Practice Centers Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, based on the standard GRADE system (GRADE 2009; Owens 2010), to assess domain‐specific and overall strength of evidence on three relevant outcomes: length of stay or admission rate, clinical severity scores and adverse events. Two review authors (LH, RF) independently graded the body of evidence using adapted decision rules.

We examined the following domains: risk of bias, consistency, directness and precision. Risk of bias was considered as low or medium, as we only included RCTs. There is limited evidence regarding clinically significant and patient‐important between‐group differences in this field. We therefore defined a priori thresholds of clinical relevance based on expert opinion and GRADE guidance for the precision domain: risk ratio reduction > 20% for admissions, reduction in LOS > 0.5 days and clinical scale effect sizes based on GRADE guidance (GRADE 2009). We graded overall strength of evidence 'high', 'moderate' or 'low' based on the likelihood of further research changing our confidence in the estimate of effect (when evidence was unavailable or did not permit estimation of an effect, it was considered insufficient).

All decisions were made explicitly and inter‐rater agreement was calculated (data available from authors). We resolved discrepancies by consensus among two review authors (LH, RF).

Measures of treatment effect

We pooled dichotomous variables using risk ratios (RRs). We derived the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) for significant results from primary outcomes. Since the only comparison with significant differences was based on a single trial, the NNTB is shown for that trial's baseline risk.

We analysed measurement scale outcomes as continuous variables. For continuous variables measured on the same scale (for example, respiratory rate), we calculated mean differences (MD) for individual studies and mean differences for the pooled estimates. For those measured on different scales (for example, clinical scores), we calculated MDs for separate studies and standardised MD (SMD) for the pooled estimates. We used changes from baseline for all continuous variables.

Unit of analysis issues

Some of the studies included in this review were multi‐arm or factorial studies in which more than two intervention groups were eligible to contribute several comparisons to a single meta‐analysis. For example, a trial might compare glucocorticoid versus placebo in two arms, and glucocorticoid + bronchodilator versus placebo + bronchodilator in another two arms, with both contributing to the overall glucocorticoid versus placebo comparison. When the comparisons were independent, i.e. with no intervention group in common, we included data from these arms with no transformation and we shown them separately in each forest plot. If needed and feasible, we pooled the active groups to avoid double‐counting of the comparator group when there was more than one active group: for example, two glucocorticoid groups versus placebo. We did not include any treatment groups twice in the same meta‐analysis.

Guidance regarding the analysis of factorial trials mandates caution when results suggest positive interaction/additive effects ('synergism') between study treatments (McAlister 2003; Montgomery 2003). This was the case for a large trial included in this review. We therefore chose to include comparisons separately in meta‐analysis ('within the table analysis'): for example, for the glucocorticoid versus placebo comparison, we included separately glucocorticoid + bronchodilator versus placebo + bronchodilator and glucocorticoid + placebo versus double placebo. We also performed sensitivity analysis pooling all arms ('at the margins analysis').

Dealing with missing data

We extracted information on incomplete outcome data and we classified trials that performed intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis as either ITT with all data, ITT with imputation of missing data, ITT with available case analysis, per protocol analysis or treatment‐received analysis (Higgins 2011). We did not impute missing data for drop‐outs. We estimated unreported means from figures or imputed from medians if possible. We computed standard deviations (SDs) from available data (i.e. standard errors, confidence intervals (CI) or P values) when missing. Failing this, we estimated them from ranges and inter‐quartile ranges, or imputed them from a similar study. When standard deviations of change from baseline values were unavailable, we estimated correlation at 0.5 (Follmann 1992; Wiebe 2006). We occasionally encountered clinical score results presented as dichotomous data, for example, using a cut‐off score or time‐to‐event analysis. When methods were feasible and assumptions judged reasonable, we used existing approaches to re‐express odds ratios as standardised mean differences, thus allowing dichotomous and continuous data to be pooled together (Higgins 2011). When data were unavailable for one of the predefined timings of outcome measurement, we used the time point closest or any time point in the range. If there was more than one time point, we chose the one with the largest magnitude of change.

We did not contact trial authors of the individual studies to obtain additional data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We used the following intervals for interpreting I2 statistic values: 0% to 30% low heterogeneity; 30% to 50% moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 75% substantial heterogeneity; and 75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting biases for the main comparisons and primary outcomes by visual interpretation of funnel plots and testing for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger test) (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We meta‐analysed quantitative results within the different comparisons when studies were consistent on clinical grounds and had available outcome data; we imposed no restrictions based on risk of bias. We performed separate meta‐analyses for studies involving inpatients and outpatients.

We combined results using random‐effects models regardless of heterogeneity, due to expected differences in interventions, outcomes and measurement instruments. We calculated fixed‐effect models in a sensitivity analysis. We conducted meta‐analyses of dichotomous outcomes using Mantel‐Haenszel methods. We used inverse variance methods for continuous outcomes and measurement scales, and combined dichotomous and continuous data into a standardised mean difference whenever needed (Higgins 2011). All results are reported with 95% CI. We used Review Manager software for data management and analysis (RevMan 2012).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate heterogeneity by conducting subgroup analyses based on pre‐specified study‐ and participant‐level characteristics. The following subgroups were considered:

Protocolised use of bronchodilators (studies with protocolised use versus no/unclear protocolised use).

RSV status (studies with all participants exclusively RSV‐positive versus some RSV‐negative/unspecified RSV status).

Age of participants (studies with all participants exclusively less than 12 months of age versus some participants older than 12 months/unspecified age).

Atopy (studies with all participants exclusively atopic versus some participants not atopic/unspecified atopic status).

Glucocorticoid: type of glucocorticoids; and daily and overall dose (high versus low).

We explored potential positive or negative (i.e. 'synergistic' or 'antagonistic') interactions between glucocorticoids and bronchodilators by distinguishing trials where bronchodilator use was protocolised (i.e. comparing glucocorticoids + bronchodilator versus placebo + bronchodilator) from studies where use was either at the discretion of the physician or not allowed (Gurusamy 2009). The choice of RSV, age and atopy was based on clinical or biological evidence suggesting possible effect modification of glucocorticoid effects by these parameters. We studied drug type and dose to explore distinct glucocorticoid pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties; dosing was based on prednisolone equivalents.

We planned to perform subgroup analyses only on the review's primary outcomes. We also collected data from studies that analysed these subgroups at a study level. We assessed subgroup differences comparing changes in effect estimate and CI overlap; statistical tests or meta‐regression techniques were not used.

Sensitivity analysis

We decided a priori to perform sensitivity analyses on primary outcome results of trials with overall low risk of bias. We also checked for differences in the direction and magnitude of primary outcome results when using fixed‐effect models, as well as using pooled data from all factorial trial arms ('at the margins analysis').

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

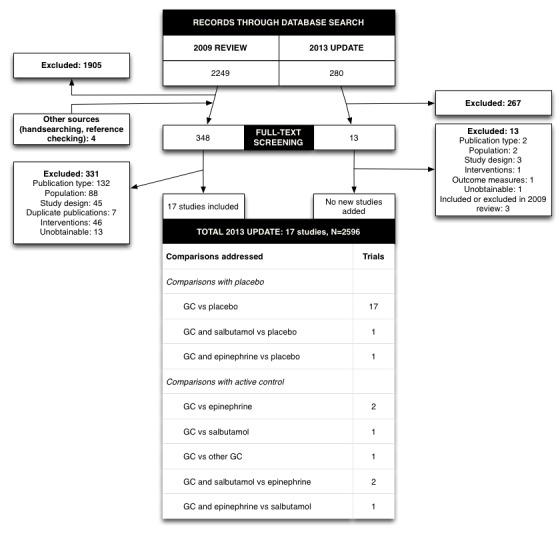

The initial 2009 comprehensive search of all electronic databases identified 2249 records, of which 344 were potentially relevant. Handsearching had identified four more studies and overall 348 full‐text articles had been assessed for eligibility. Of 91 studies that used glucocorticoids, 17 trials fulfilled inclusion criteria.

The 2013 search identified 280 further records, of which 13 were assessed for eligibility using full text but all were excluded (flowchart in Figure 1).

1.

Flow of citations through the search and screening procedures of the 2009 review and this 2012 update, studies included in the review and comparisons addressed (GC: glucocorticoids)

Included studies

We included 17 trials with 2596 randomised participants. We considered different comparisons separately between glucocorticoids, alone or with fixed co‐interventions, and either placebo or active controls. Included trials contributed to one or more comparisons, depending on trial arms (Figure 1).

Design, centres and sample sizes

Fifteen trials were parallel‐designed, 14 of which were double‐armed (Bentur 2005; Berger 1998; Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; De Boeck 1997; Goebel 2000; Gomez 2007; Klassen 1997; Mesquita 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003) and one was six‐armed (Barlas 1998). Two trials were factorial two‐by‐two (Kuyucu 2004; Plint 2009).

Eleven trials were single‐centred and five included multiple centres (range: 2 to 20) (Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000; Plint 2009; Teeratakulpisarn 2007); one trial did not clearly report this item (Bentur 2005). All trials were conducted in a single country, either in North, Central or South America, Europe and the Middle East or Asia.

Sample size calculations were reported in 12 trials (Bentur 2005; Berger 1998; Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; Klassen 1997; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003); the outcome used for sample size calculation was the reported primary outcome in all except one trial (Richter 1998). The overall median number of participants per trial was 72 (range 32 to 800), with two large trials counting 600 and 800 (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009, respectively), and all others fewer than 200.

Funding was reported in nine studies, three of which had pharmaceutical industry support (Cade 2000; Richter 1998; Schuh 2002).

Setting and participants

Outpatients were included in eight trials, with 1824 randomised participants and a median of 85 participants per trial (range: 42 to 800) (Barlas 1998; Berger 1998; Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000; Kuyucu 2004; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Schuh 2002). Outpatient settings mostly included paediatric emergency departments. Nine trials included inpatients only, with 772 participants and a median of 61 participants per trial (range: 32 to 179) (Bentur 2005; Cade 2000; De Boeck 1997; Gomez 2007; Klassen 1997; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003). Few details were reported regarding criteria for hospitalisation and the type of admission unit in which patients received care, except for one inpatient trial report (Teeratakulpisarn 2007).

In most trials bronchiolitis was defined by clinical findings; wheezing was always required. Three trials restricted inclusion to bronchodilator responders (Goebel 2000 ‐ outpatients; Teeratakulpisarn 2007 and Zhang 2003 ‐ inpatients). Seven trials only included participants under the age of 12 months, all of which had a mean or median participant age below six months (Bentur 2005; Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Zhang 2003).

Bronchiolitis severity thresholds were used for inclusion in eight outpatient (Barlas 1998; Berger 1998; Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000; Kuyucu 2004; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Schuh 2002) and two inpatient trials (Gomez 2007; Klassen 1997). Severity was based on clinical scales or respiratory parameters, and thresholds varied. The Respiratory Distress Assessment Instrument (RDAI) baseline score thresholds varied between two and six (less than four usually considered mild bronchiolitis).

Thirteen trials reported testing for RSV at least in a portion of participants, and three trials only included RSV‐positive patients (Bentur 2005; Cade 2000; De Boeck 1997). Prevalence of RSV in the remaining 10 trials varied from 33% to 89% (Barlas 1998; Berger 1998; Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000; Klassen 1997; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002).

Atopic status was reported in nine trials (Barlas 1998; Berger 1998; Cade 2000; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003), while one trial reported a family history of wheezing (Corneli 2007). Definitions for atopy and methods of assessment were rarely provided, and when reported were heterogeneous. No trials excluded participants with a history of atopy.

Children with chronic cardiac, pulmonary or neurological conditions or immunodeficiency were frequently excluded. All or some premature infants were explicitly excluded in seven trials (Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; De Boeck 1997; Goebel 2000; Plint 2009; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007). Other criteria for exclusion were length of illness and glucocorticoid‐related parameters (previous use, history of adverse events, specific contraindications to their use).

Subgroup analyses within studies were reported in five trials (Bentur 2005; Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; Plint 2009; Teeratakulpisarn 2007), two of which being pre‐specified (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009). Subgroups were based on age, RSV status, family or personal history of atopy and eczema, duration and severity of illness, and exposure to smoke and/or dampness.

Interventions

There was heterogeneity regarding the choice of glucocorticoid, its dosage, route of administration and duration of treatment. Dexamethasone was the most frequently tested drug (11 trials). Nine trials used systemic dexamethasone, either oral (Corneli 2007; Klassen 1997; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Schuh 2002), intramuscular (Kuyucu 2004; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007) or intravenous (De Boeck 1997). Single‐day doses were administered for one to five days. Initial dosing was higher (0.5 to 1 mg/kg), with later doses ranging from 0.15 to 0.6 mg/kg. The highest overall dose was seen in Plint 2009 and Schuh 2002 (1 mg/kg followed by 0.6 mg/kg for five days), and the lowest in Mesquita 2009 (single‐dose 0.5 mg/kg). Two trials used inhaled dexamethasone (0.2 mg to 0.25 mg every four to six hours), at least for one day, or until discharge for inpatients (Bentur 2005; Gomez 2007). Systemic prednisone or prednisolone were tested in four trials, three oral (Berger 1998; Goebel 2000; Zhang 2003) and one intravenous (Barlas 1998). Duration varied between one and five days (1 to 2 mg/kg/day, once or twice daily). Three trials used inhaled budesonide (0.5 mg to 1 mg, once or twice daily) for one to six weeks (Barlas 1998; Cade 2000; Richter 1998).

Details on placebos were reported in nine trials. Inhaled placebos included mist (Barlas 1998) and 0.9% saline (Bentur 2005; Richter 1998). Protocolised standard of care was used as a control arm in Zhang 2003.

Eleven trials used protocolised bronchodilators in both glucocorticoid and placebo arms. The choice of bronchodilator, its dose and frequency varied substantially. Seven trials used salbutamol (Barlas 1998; Berger 1998; Goebel 2000; Gomez 2007; Klassen 1997; Kuyucu 2004; Schuh 2002), four used epinephrine (Bentur 2005; Kuyucu 2004; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009) and one used salbutamol and ipratropium bromide (De Boeck 1997). Nebulised salbutamol was administered during emergency department stay (first two to four hours), or each four to six hours at home or during hospitalisation (1.5 mg to 2.5 mg, or 0.15 mg/kg). Oral administration was also allowed in Goebel 2000. Nebulised epinephrine was administered every six hours to inpatients, or once or twice in the emergency department for outpatients (1 mg to 3 mg). All other trials used bronchodilators at the discretion of the attending physician, often with guidance on the choice of drug and dosage. Additional use of glucocorticoids was often restricted. Supportive measures, i.e. oxygen and intravenous or nasogastric fluids, were usually reported.

Outcomes

Pre‐defined primary outcomes were specified in 12 trials (Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000; Klassen 1997; Kuyucu 2004; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003), three of which reported more than one primary outcome (Kuyucu 2004; Richter 1998; Teeratakulpisarn 2007). Only the two largest trials used admission as a primary outcome (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009). Other primary outcomes included clinical scales (Goebel 2000; Klassen 1997; Kuyucu 2004; Mesquita 2009; Richter 1998; Schuh 2002), clinical severity parameters or duration of disease (Kuyucu 2004; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007) and symptoms (Cade 2000; Zhang 2003). Timings of primary outcome assessment were reported in 11 trials, six of which used multiple time points. Sample size calculations were either not reported or based on secondary outcomes in Goebel 2000, Kuyucu 2004 and Richter 1998.

Reported outcomes included healthcare use domains and clinical severity parameters (all trials), pulmonary function (De Boeck 1997), patient/parent‐reported symptoms and status (seven trials: Berger 1998; Cade 2000; Plint 2009; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003) and other outcomes, including adverse events (10 trials: Bentur 2005; Cade 2000; Corneli 2007; Klassen 1997; Kuyucu 2004; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003). Not all outcome and time point results were reported.

Admission rates were assessed in all eight outpatient trials, both by day 1 (all trials) and day 7 (three trials; Corneli 2007; Plint 2009; Schuh 2002). Kuyucu 2004 and Goebel 2000 reported admissions by days 5 and 6, respectively, and were pooled with day 7 results. LOS was reported in eight of nine inpatient trials (except Roosevelt 1996) and three outpatient trials (Berger 1998; Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000). Criteria for admission or discharge were rarely reported. Considerable variability was found in control group admission rates (from 0% to 44% by day 1, and 0% to 49% by day 7) and mean LOS (0.8 to 6.6 days) (Table 3). Hospital re‐admissions for inpatients and return healthcare visits up to one month were mentioned in six trials, with variable assessment methods (Berger 1998; Klassen 1997; Plint 2009; Roosevelt 1996; Schuh 2002; Teeratakulpisarn 2007).

1. Placebo group risk of admission/length of stay.

| Study | Placebo group ‐ participants | Placebo group ‐ primary outcomes | |

| OUTPATIENT STUDIES | Risk of admission day 1 (%) | Risk of admission day 7 (%) | |

| Barlas 1998 | 30 | 17% | NR |

| Berger 1998 | 18 | 11% | NR |

| Corneli 2007 | 295 | 41% | 49% |

| Goebel 2000 | 24 | 8% | 21% |

| Kuyucu 2004 | 11 | 0% | 0% |

| Mesquita 2009 | 32 | 22% | NR |

| Plint 2009 | 201 | 18% | 26% |

| Schuh 2002 | 34 | 44% | 47% |

| INPATIENT STUDIES | Length of stay (mean ± SD days) | ||

| Bentur 2005 | 32 | 6.3 ± 8.8 | |

| Cade 2000 | 79 | 2 ± 2.2 | |

| De Boeck 1997 | 15 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | |

| Gomez 2007 | 25 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |

| Klassen 1997 | 32 | 2 ± 0.7 | |

| Richter 1998 | 19 | 3 ± 1.6 | |

| Teeratakulpisarn 2007 | 85 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | |

| Zhang 2003 | 24 | 5 ± 3.3 | |

NR = not reported SD = standard deviation

Clinical severity scales were assessed in all except one trial (Zhang 2003), often using more than one scale (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Schuh 2002). Measurement instruments were developed specifically for nine trials (Barlas 1998; Bentur 2005; Berger 1998; Cade 2000; De Boeck 1997; Goebel 2000; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007), mostly based on previous scales by Schuh 1990, Tal 1983 and Westley 1978. The RDAI was used in eight trials (Corneli 2007; Gomez 2007; Klassen 1997; Kuyucu 2004; Mesquita 2009; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Schuh 2002). Corneli 2007 and Plint 2009 also used the Respiratory Assessment Change Score (RACS), based on RDAI and respiratory rate (both originally reported by Lowell 1987). All scales included items on wheezing and accessory muscle use; other respiratory items (for example, timing or location of wheezing) or disease domains (for example, general status, nutrition) were less frequently used. Oxygen saturation, respiratory and heart rates were reportedly measured in most trials. Heterogeneity in timings of repeated measurements was found; the two most frequently time points assessed were 60 minutes and three to six hours.

Measurement of patient/parent‐reported symptoms was inconsistent. Five trials reported symptoms data (Cade 2000; Plint 2009; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007). There were differences in the specific symptoms addressed (for example, respiratory, feeding), the measurement instrument used (i.e. questionnaires, diaries) and the time points of assessment. No trial reported the use of generic or disease‐specific quality of life instruments.

Other reported outcomes included temperature measurements (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009; Roosevelt 1996), time to resolution or length of illness (Roosevelt 1996; Zhang 2003), and duration of oxygen therapy or fluids (Bentur 2005; Richter 1998; Roosevelt 1996; Teeratakulpisarn 2007; Zhang 2003). Data on the use of bronchodilator co‐interventions were often reported as an outcome.

Adverse events were mentioned in six trials (Corneli 2007; Goebel 2000; Klassen 1997; Kuyucu 2004; Plint 2009; Teeratakulpisarn 2007). Five of these studies assessed specific gastrointestinal, endocrine or infectious complications. There was heterogeneity and incomplete reporting regarding which adverse events were pre‐specified, their definitions and measurement methods. All adverse effects were short‐term and no study assessed long‐term harms.

Excluded studies

Eighty‐four out of 361 excluded papers involved glucocorticoids. Motives for exclusion from this subset mostly included inappropriate population (for example, trials including participants with a history of previous wheezing, or > 24 months old), type of publication and non‐RCT study design (Characteristics of excluded studies).

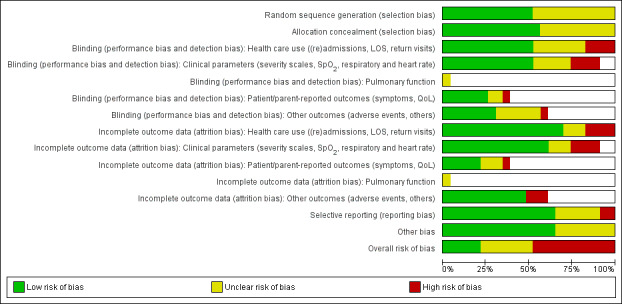

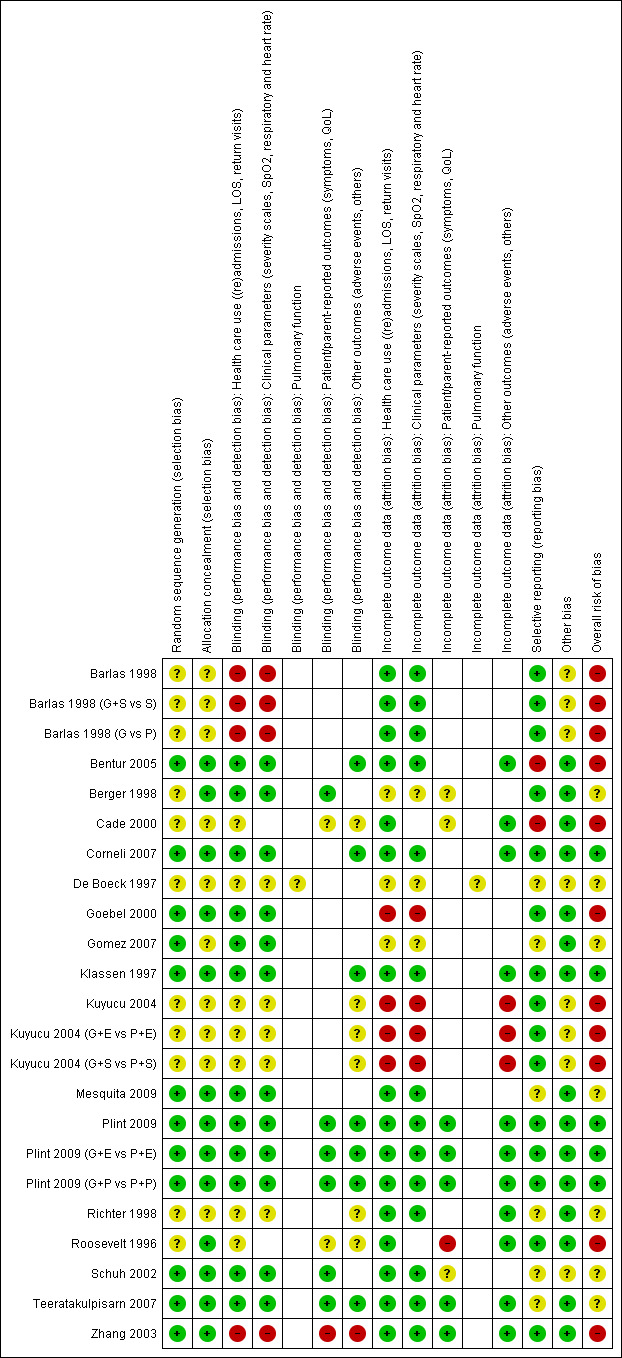

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed overall risk of bias as 'low' in three trials, as 'high' in seven and 'unclear' in seven. The glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo comparison included one low risk of bias trial. All other comparisons included mostly high risk of bias trials (Figure 2).

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.*

*For multi‐arm studies (Barlas 1998, Kuyucu 2004 and Plint 2009), we included one overall assessment for all trial comparisons, and two assessments for each separate comparison of glucocorticoids versus placebo (with or without protocolised bronchodilator, or with epinephrine or salbutamol).

We found adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment in 10 and 11 trials, respectively (Figure 3). We considered blinding adequate in 10 out of 17 trials for the review primary outcomes and clinical severity parameters. Incomplete reporting explained most 'unclear' assessments. Incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed in 12 out of 17 studies for the review primary outcomes, and 11 out of 17 for clinical severity outcomes; it was unclear or inadequate when there was imbalanced attrition between groups, mostly in longer follow‐up assessments.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.*

*For multi‐arm studies (Barlas 1998, Kuyucu 2004 and Plint 2009), we included one overall assessment for all trial comparisons, and two assessments for each separate comparison of glucocorticoids versus placebo (with or without protocolised bronchodilator, or with epinephrine or salbutamol).

We considered nine out of 17 studies free from risk of selective outcome reporting. Assessment of this item was challenging given the large number of outcomes reported, the diversity of measurement time points, and the fact that trial protocols were not available. Using trial registry searches, we identified three trial registers and used that data to complete assessments (Corneli 2007; Plint 2009; Teeratakulpisarn 2007).

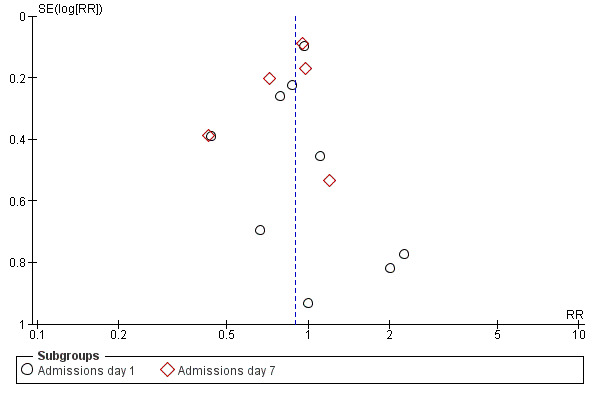

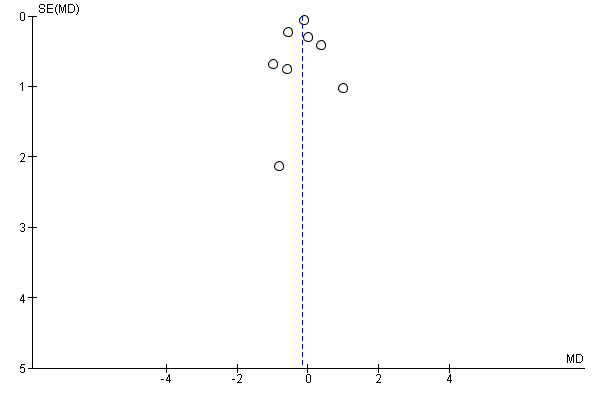

Regarding publication bias and small study effects, there was no asymmetry in funnel plots for the primary outcomes in the glucocorticoids versus placebo comparison by visual inspection or statistical testing (Egger test for admissions and length of stay, P = 0.98 and P = 0.77, respectively) (Figure 4; Figure 5).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Steroid versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Admissions (days 1 and 7) (outpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Steroid versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Length of stay (inpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

Other types of bias assessed as 'unclear' included baseline imbalances, or active arm contamination with other related co‐interventions (Kuyucu 2004 and Schuh 2002, respectively).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Glucocorticoid versus placebo: summary of findings.

| Glucocorticoid versus placebo for acute viral bronchiolitis in infants and young children | |||||

| Patient or population: infants and young children with acute viral bronchiolitis Settings: outpatients and inpatients Intervention: glucocorticoid versus placebo | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Steroid versus placebo | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Placebo | Steroid | ||||

|

Admissions (outpatients) Follow‐up: day 1 |

Medium risk population |

RR 0.92 (0.78 to 1.08) |

1762 (8) | high | |

| 162 per 1000 | 149 per 1000 (126 to 175) | ||||

|

Admissions (outpatients) Follow‐up: day 7 |

Medium risk population |

RR 0.86 (0.7 to 1.06) |

1530 (5) | moderate | |

| 250 per 1000 | 215 per 1000 (175 to 265) | ||||

|

Length of stay (inpatients) days |

The mean length of stay ranged across control groups from 0.8 to 6.6 days | The mean length of stay in the intervention groups was 0.18 lower (0.39 lower to 0.04 higher) | 633 (8) | high | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (for example, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Assumed risk for admissions was based on the median control group risks across the studies included in the meta‐analysis (medium risk).

Summary of findings 2. Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo: summary of findings.

| Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo for acute viral bronchiolitis in infants and young children | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants and young children with acute viral bronchiolitis Settings: outpatients Intervention: glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Steroid versus placebo | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Steroid | |||||

|

Admissions (outpatients) Follow‐up: day 1 |

179 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 (72 to 186) | RR 0.65 (0.4 to 1.05) | 400 (1) | Low | NNT: not calculated for non‐significant findings |

|

Admissions (outpatients) Follow‐up: day 7 |

264 per 1000 | 169 per 1000 (116 to 251) |

RR 0.65 (0.44 to 0.95) |

400 (1) | Low | NNT: 11 (95% CI 7 to 76) (based on unadjusted analysis results) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (for example, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval NNT: number needed to treat RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Assumed risk for admissions was based on the control group risk in the single study included (Plint 2009).

Results are summarised by comparison, setting and type of outcome. GRADE assessments for the two main comparisons ‐ glucocorticoid versus placebo and glucocorticoid and bronchodilator versus placebo are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. All meta‐analyses used random‐effects models; fixed‐effect models did not modify the direction and magnitude of results unless mentioned.

2. GRADE assessments: glucocorticoid versus placebo.

| Population | Outcome | Number of studies | Number of participants | GRADE domains | Strength of evidence | Intervention favoured | |||

| Risk of bias | Consistency | Directness | Precision | ||||||

| GLUCOCORTICOID versus PLACEBO | |||||||||

| Inpatients | Length of stay | 8 | 633 | Medium | Consistent | Direct | Precise | High | No difference |

| Clinical score : 3 to 6 hours | 1 | 26 | Medium | Unknown | Direct | Imprecise | Low | Glucocorticoid | |

| Clinical score : 6 to 12 hours | 3 | 175 | Medium | Consistent | Direct | Imprecise | Moderate | Glucocorticoid | |

| Clinical score : 12 to 24 hours | 3 | 230 | Medium | Consistent | Direct | Imprecise | Moderate | No difference (glucocorticoid favoured) | |

| Clinical score : 24 to 72 hours | 4 | 113 | Medium | Inconsistent | Direct | Imprecise | Low | No difference (glucocorticoid favoured; very close to significant) | |

| Outpatients | Admissions day 1 | 8 | 1762 | Medium | Consistent | Direct | Precise | High | No difference |

| Admissions up to day 7 | 5 | 1530 | Low | Consistent | Direct | Imprecise | Moderate | No difference | |

| Clinical score: 60 minutes | 4 | 1006 | Low | Consistent | Direct | Precise | High | No difference | |

| Clinical score: 120 minutes | 3 | 214 | Medium | Consistent | Direct | Imprecise | Moderate | No difference | |

| Clinical score: 3 to 6 hours | 2 | 808 | Medium | Inconsistent | Direct | Precise | Moderate | No difference | |

| Clinical score: 12 to 24 hours | 1 | 69 | Medium | Unknown | Direct | Imprecise | Low | No difference | |

| Clinical score: 3 to 10 days | 4 | 224 | Medium | Inconsistent | Direct | Imprecise | Low | No difference | |

| Inpatients/outpatients | Adverse events | 5 | 1123 | Low | Consistent | Direct | Precise | Moderate | No difference |

3. GRADE assessments: glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo.

| Population | Outcome | Number of studies | Number of participants | GRADE domains | Strength of evidence | Intervention favoured | |||

| Risk of bias | Consistency | Directness | Precision | ||||||

| GLUCOCORTICOID AND EPINEPHRINE versus PLACEBO | |||||||||

| Outpatients | Admissions day 1 | 1 | 400 | Low | Unknown | Direct | Imprecise | Low | Favours epi + dex but NS |

| Admissions day 7 | 1 | 400 | Low | Unknown | Direct | Imprecise | Low | Epi + dex | |

| Clinical score: 60 minutes | 1 | 400 | Low | Unknown | Direct | Precise | Moderate | Epi + dex | |

| Adverse events | 1 | 400 | Low | Unknown | Direct | Imprecise | Low | No difference | |

dex = dexamethasone epi = epinephrine NS = non‐significant

Glucocorticoid versus placebo

Outpatients

Primary outcomes

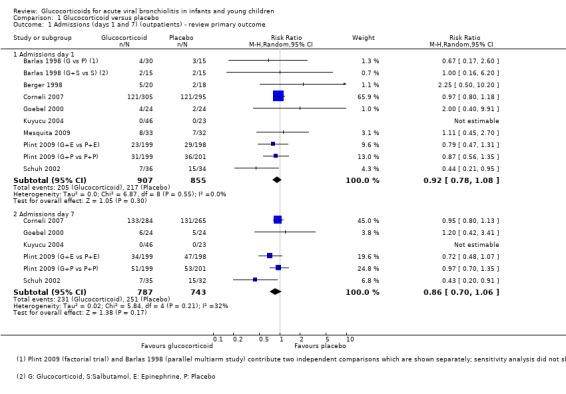

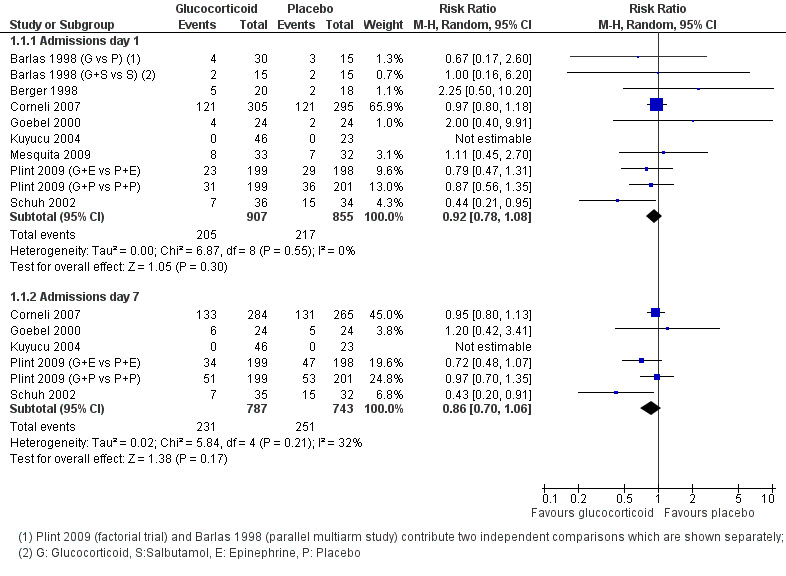

All eight outpatient studies reported admissions by day 1, and five also reported admissions by day 7. Complete outcome data were available for 1762 participants by day 1 (out of 1824 randomised) and 1530 participants by day 7 (out of 1612 randomised).

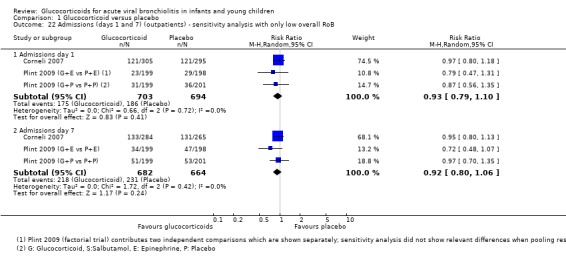

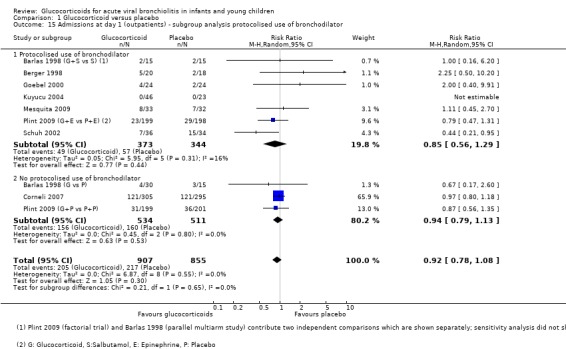

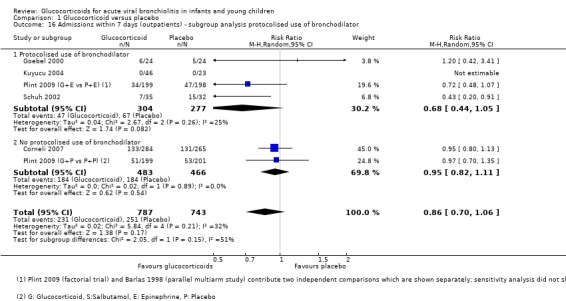

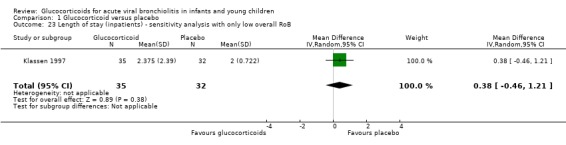

The pooled risk ratios (RRs) for admissions by days 1 and 7 were 0.92 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.08) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.7 to 1.06), respectively, with no significant differences between groups (Analysis 1.1; Figure 6). Heterogeneity was low for day 1 results and moderate for day 7 (I2 statistic = 0% and 31%, respectively). There was no relevant change in the magnitude or direction of results when using pooled data from both Plint 2009 arms. Sensitivity analyses for both trials with low overall risk of bias showed comparable results (Analysis 1.22). Overall strength of evidence for these findings was high for day 1 results and moderate for day 7, the latter due to some imprecision in the effect estimate (Table 4; Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 1 Admissions (days 1 and 7) (outpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Steroid versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Admissions (days 1 and 7) (outpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 22 Admissions (days 1 and 7) (outpatients) ‐ sensitivity analysis with only low overall RoB.

Subgroup analysis of studies using protocolised bronchodilator found lower pooled RRs for admissions by both days 1 and 7, but the CIs between subgroups overlapped (Analysis 1.15; Analysis 1.16). For admissions by day 7, the estimate for RR was 0.68 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.05) for protocolised bronchodilator trials (four trials, 581 participants), and 0.95 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.11) for other trials (two trials, 949 participants). Heterogeneity was low in both subgroups.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 15 Admissions at day 1 (outpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis protocolised use of bronchodilator.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 16 Admissions within 7 days (outpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis protocolised use of bronchodilator.

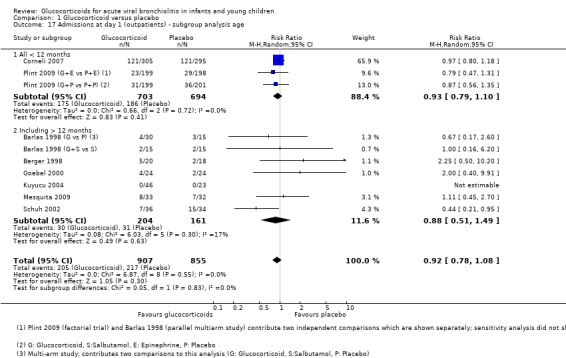

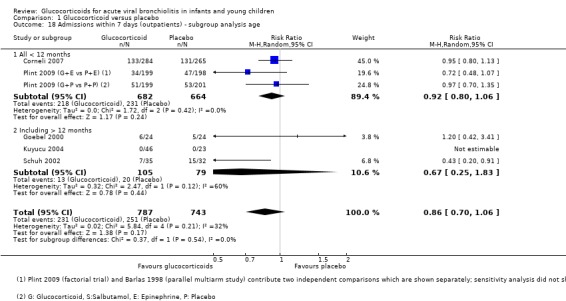

The two largest outpatient studies only included participants under 12 months of age, while six smaller studies also included older patients (Analysis 1.17; Analysis 1.18). For admissions by day 7, estimates were 0.92 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.06) and 0.67 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.83), for < 12 months (two trials, 1346 participants) and trials including older participants (three trials, 184 participants), respectively. Trials including older participants had a lower effect estimate, but a large CI overlapped with the other subgroup and there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 statistic = 60%).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 17 Admissions at day 1 (outpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis age.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 18 Admissions within 7 days (outpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis age.

No subgroup analysis according to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or atopic status was performed, since no outpatient trial restricted inclusion based on these parameters. Corneli 2007 and Plint 2009 reported pre‐specified subgroup analyses based on atopic status, with no statistically significant differences. Plint 2009 also reported no differences according to RSV status, duration of illness and severity. We chose not to perform analyses based on glucocorticoid type or dose due to heterogeneity in glucocorticoid schemes.

Secondary outcomes

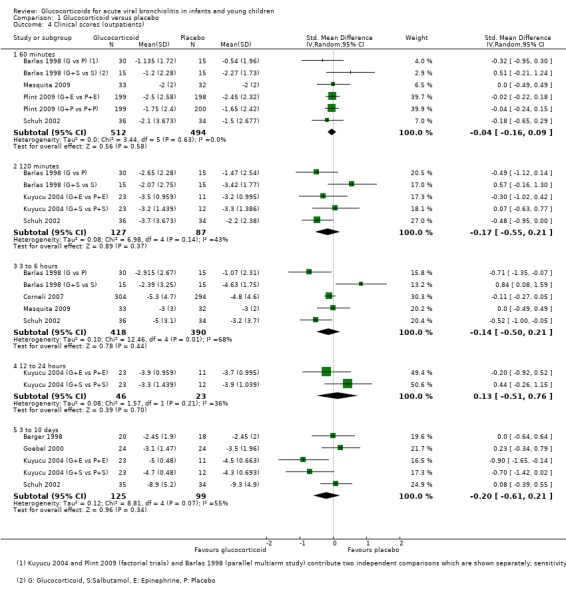

Clinical score data were available for time points/intervals between 60 minutes and 3 to 10 days (Analysis 1.4; Figure 7). Different sets of studies with different scales contributed to each time point, with most data at 60 minutes (four trials, 1006 participants); no trial assessed the period between 24 to 72 hours. There were no significant differences between groups at any time point. Strength of evidence for these findings was high at 60 minutes, with precise and consistent results (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.04; 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.09; I2 statistic = 0%). Evidence was weaker for later results due to imprecision and substantial heterogeneity.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 4 Clinical scores (outpatients).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Steroid versus placebo, outcome: 1.4 Clinical scale scores (outpatients) (change from baseline data).

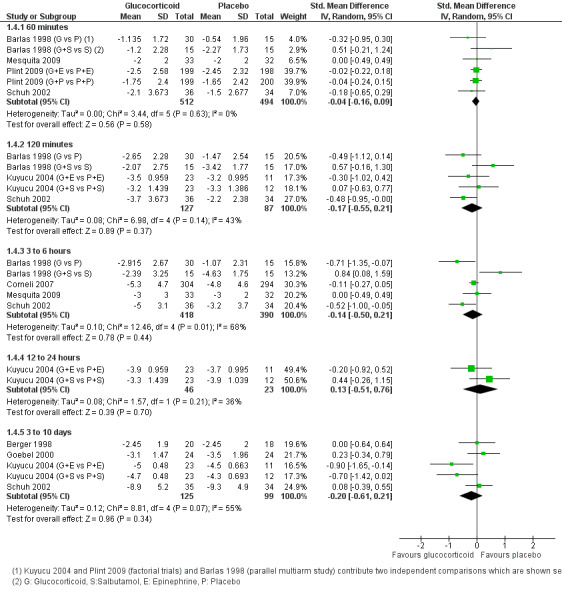

Six trials reported outcome data on oxygen saturation between 60 minutes and 24 to 72 hours (Analysis 1.6). Data were most frequently reported at 60 minutes (three trials, 936 participants). At three to six hours, results favoured placebo (mean difference (MD) ‐0.43; 95% CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.02; units: %), while for all other time points there were no significant differences between groups.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 6 O2 saturation (outpatients).

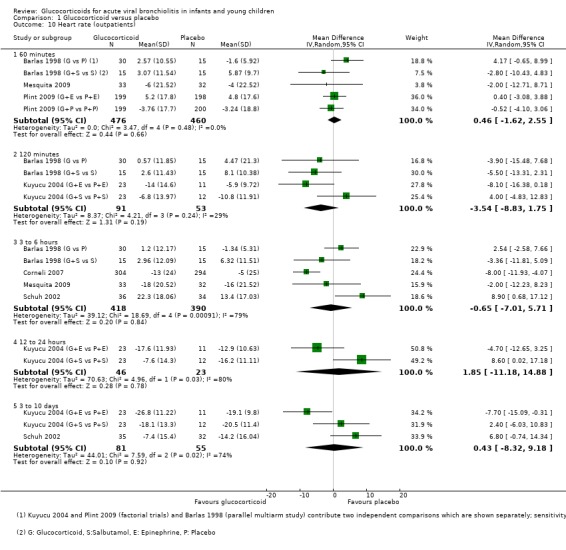

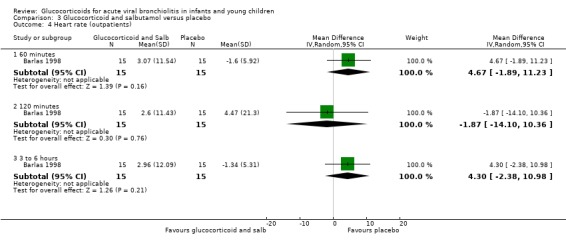

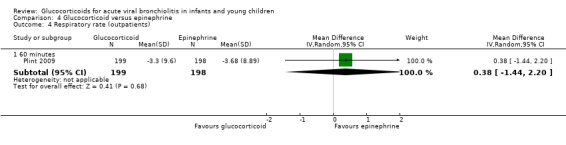

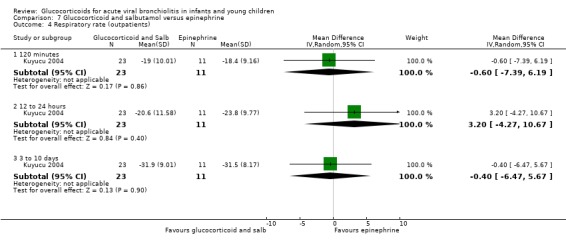

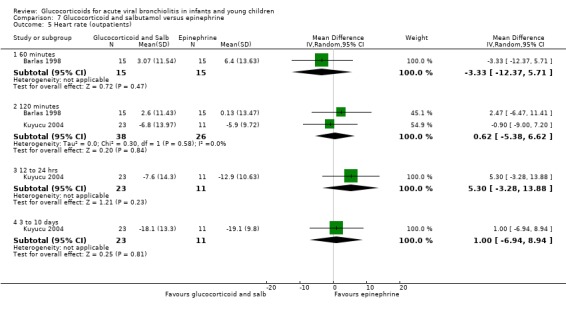

Respiratory and heart rate data were both reported in six outpatient trials, between 60 minutes and 3 to 10 days (Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.10). The most frequently assessed time point for both outcomes was 60 minutes; no trial assessed the period between 24 to 72 hours. There were no significant differences between groups for any of these outcomes.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 8 Respiratory rate (outpatients).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 10 Heart rate (outpatients).

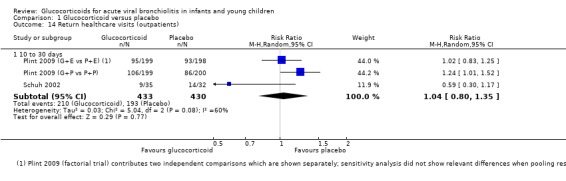

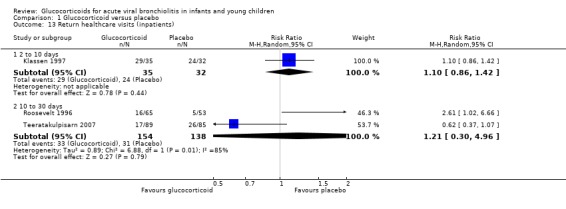

Regarding other health services outcomes, pooled data from three trials (255 participants) reporting length of stay (LOS) of admitted patients did not show significant differences between groups (Analysis 1.3). Return to healthcare visits for bronchiolitis symptoms were only assessed in two trials (863 participants), both showing considerable event rate for a three to four‐week follow‐up period (26% to 53% in all groups; Table 6). Pooled results did not show significant differences between groups (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.35) (Analysis 1.14).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 3 Length of stay (outpatients).

4. Hospital re‐admissions and return healthcare visits (in‐ and outpatients).

| Study | Population | Duration of follow‐up | Glucocorticoid‐including group | Placebo or comparator group | Notes |

| GLUCOCORTICOID AND EPINEPHRINE versus PLACEBO: HOSPITAL RE‐ADMISSIONS | |||||

| Roosevelt 1996 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 14 | 0 | 0 | (No events in either group) |

| Klassen 1997 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 7 | 4/35 (11%) | 1/32 (3%) | P = 0.36 |

| Teeratakulpisarn 2007 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 30 | 3/89 (3%) | 7/85 (8%) | |

| GLUCOCORTICOID versus PLACEBO: RETURN HEALTHCARE VISITS* | |||||

| Plint 2009 (epinephrine ‐ E; dexamethasone ‐ D; placebo ‐ P) |

Outpatients | Days 1 to 22 | D + E 95/199 (48%) |

P + E 93/198 (47%) |

Return to the health care provider for bronchiolitis symptoms Difference between dexamethasone + placebo versus placebo + placebo, was significant in the unadjusted analysis (P = 0.04) |

| D + P 106/199 (53%) |

P + P 86/201 (43%) |

||||

| Schuh 2002 | Outpatients | Days 7 to 28 | 9/35 (26%) | 14/32 (44%) | Medical visits for continuing symptoms; P = 0.069 |

| Klassen 1997 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 7 | 29/35 (83%) | 24/32 (75%) | P = 0.77 |

| Roosevelt 1996 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 14 | 16/65 (25%) | 5/53 (9%) | P = 0.01; reported on visits made by the physician; 69% were for non‐respiratory difficulties |

| Teeratakulpisarn 2007 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 30 | 17/89 (19%) | 26/85 (31%) | Visit to emergency room or a private clinic because of respiratory symptoms |

| GLUCOCORTICOID versus EPINEPHRINE: RETURN HEALTHCARE VISITS | |||||

| Plint 2009 (dexamethasone + placebo versus epinephrine + placebo) |

Outpatients | Days 1 to 22 | 106/199 (53%) | 93/198 (47%) | ‐ |

| GLUCOCORTICOID AND EPINEPHRINE versus PLACEBO: RETURN HEALTHCARE VISITS | |||||

| Plint 2009 (dexamethasone + epinephrine versus placebo + placebo) |

Outpatients | Days 1 to 22 | 95/198 (48%) | 86/201 (43%) | ‐ |

*Berger 1998: no difference between groups, but did not report quantitative data. Data presented as n/N (%)

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 14 Return healthcare visits (outpatients).

Plint 2009 reported data on parent‐reported symptoms regarding time to return to normal feeding, sleeping, breathing and no coughing (Table 7). There were no statistically significant differences between glucocorticoid and placebo groups. No outpatient trials assessed or reported pulmonary function or quality of life outcomes.

5. Symptoms and quality of life (in‐ and outpatients)*.

| Study | Population | Duration of follow‐up | Parameter | Glucocorticoid‐including group | Placebo or comparator group | Notes |

| GLUCOCORTICOID versus PLACEBO | ||||||

| Teeratakulpisarn 2007 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 30 | Time from treatment to being symptom free ‐ mean ± SD | 7.0 ± 5.9 | 9.0 ± 6.4 | P = 0.035 |

| Cade 2000 | Inpatients | Days 1 to 28 | Time taken for half of infants to become asymptomatic for 48 hours (95% CI) ‐ time to event analysis | 10 (10 to 13) | 12 (10 to 16) | HR 1.41 (95% CI 0.98 to 2.04), P = 0.07 |

| Days with coughing or wheezing episodes ‐ mean ± SD | 17.0 ± 7.6 days | 17.1 ± 8.5 | Mean difference: 0.91 days (95% CI ‐2.72 to 2.41), P = 0.91 | |||

| Roosevelt 1996# | Inpatients | Day 10 to 14 | No current difficulty breathing ‐ n/N (%) | 45/45 (100) | 37/42 (88) | P = 0.07 |

| Feeding and drinking well ‐ n/N (%) | 45/45 (100) | 40/42 (95) | P = 0.57 | |||

| GLUCOCORTICOID versus PLACEBO, GLUCOCORTICOID versus EPINEPHRINE, GLUCOCORTICOID AND EPINEPHRINE versus PLACEBO | ||||||

| Plint 2009 (epinephrine ‐ E; dexamethasone ‐ D; placebo ‐ P) | Outpatients | Days 1 to 22 | Time to return to normal feeding ‐ median (IQR) | D + E: 0.6 (0.2 to 1.3) D + P: 0.8 (0.3 to 1.9) P + E: 0.5 (0.2 to 1.2) P + P: 0.9 (0.3 to 2.1) | Time to return to normal feeding ‐ mean symptom duration ratio D + E versus P + P: 0.63 (unadjusted 95% CI 0.5 to 0.8)¶ Time to return to quiet breathing ‐ mean symptom duration ratio D + E versus P + P: 0.83 (unadjusted 95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) No other reported comparison was statistically significant in adjusted analysis |

|

| Time to return to normal sleeping ‐ median (IQR) | D + E: 0.7 (0.2 to 1.7) D + P: 0.8 (0.3 to 1.9) P + E: 0.8 (0.3 to 1.9) P + P: 0.8 (0.3 to 1.8) | |||||

| Time to no coughing ‐ median (IQR) | D + E: 12.6 (7.8 to 18.5) D + P: 13.8 (8.5 to 20.2) P + E: 13.2 (8.1 to 19.3) P + P: 13.3 (8.2 to 19.5) | |||||

| Time to quiet breathing ‐ median (IQR) | D + E: 3.1 (1.4 to 6.1) D + P: 3.7 (1.6 to 7.1) P + E: 3.6 (1.5 to 6.9) P + P: 3.7 (1.6 to 7.2) | |||||

*Units in days unless otherwise stated; no study assessed or reported data from generic or disease‐specific quality of life instruments; Richter 1998 also reported number of symptom‐free days for a 6‐week follow‐up period

#Roosevelt 1996 primary outcome was time to resolution (defined as number of 12 h periods needed to achieve: O2 saturation > 95% at room air, accessory muscle score = 0, wheeze = 0 or 1, and normal feeding); only association measures were reported: HR 1.3 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.3), P = 0.22

¶time to symptom relief was analysed by means of parametric survival models with Weibull distributions assumed; 95% CI adjusted for multiple analysis in a factorial trial.

CI = confidence interval HR = hazard ratio IQR = interquartile range SD = standard deviation

Inpatients

Primary outcomes

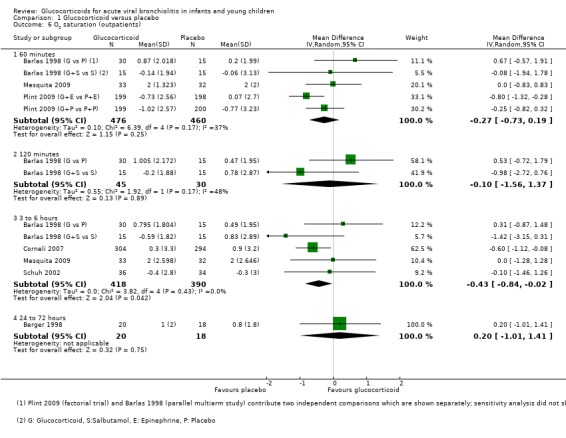

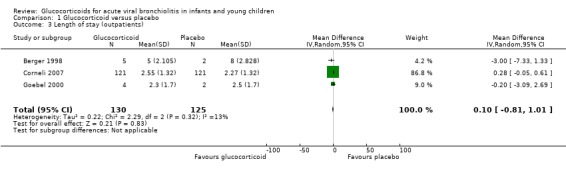

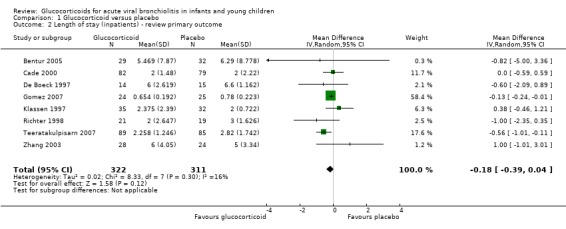

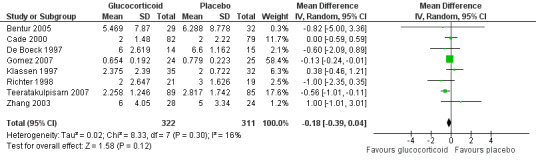

Eight inpatient trials reported data on LOS (633 participants), with no significant mean difference between glucocorticoid and placebo groups (MD ‐0.18 days; 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.04; I2 statistic = 16%) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 8). On a sensitivity analysis using fixed‐effect models and including all studies, the mean difference reached statistical significance favouring glucocorticoids, with a similar magnitude (MD ‐0.14 days; 95% CI ‐0.25 to ‐0.03). We graded the strength of evidence as high given its precision, consistency and 'Risk of bias' assessments for all included trials (Table 4; Table 1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 2 Length of stay (inpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Steroid versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Length of stay (inpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

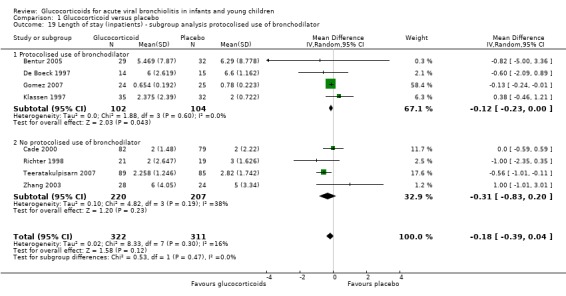

Subgroup analyses showed a statistically significant reduction in LOS in trials with protocolised bronchodilator (‐0.12 days; 95% CI ‐0.23 to ‐0.00; four trials, 206 participants), although CIs overlapped between subgroups (Analysis 1.19). Heterogeneity was low in the protocolised group results (I2 statistic = 0%) and moderate in the other subgroup (I2 statistic = 38%).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 19 Length of stay (inpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis protocolised use of bronchodilator.

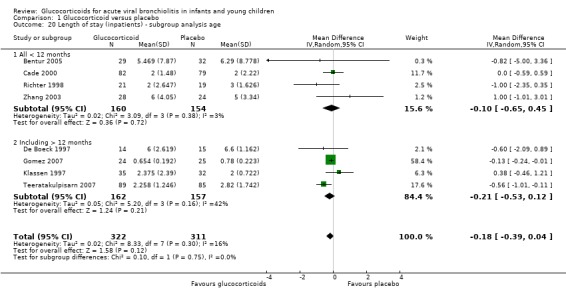

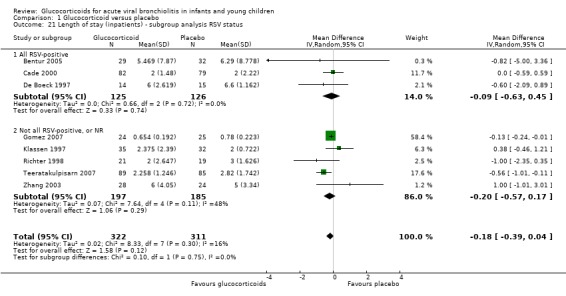

In subgroup analyses according to age and RSV status, CIs overlapped between subgroups for both parameters (Analysis 1.20 and Analysis 1.21). Heterogeneity was low in both < 12 months and RSV‐only trial results, and moderate in the other subgroups.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 20 Length of stay (inpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis age.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 21 Length of stay (inpatients) ‐ subgroup analysis RSV status.

We did not perform subgroup analyses based on atopic status and glucocorticoid type and dose for the reasons mentioned previously.

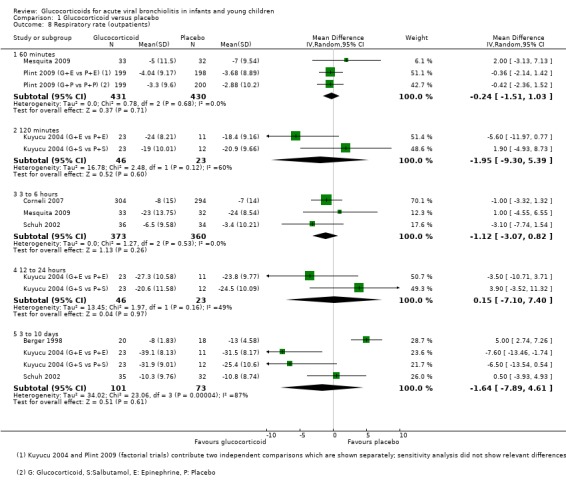

Secondary outcomes

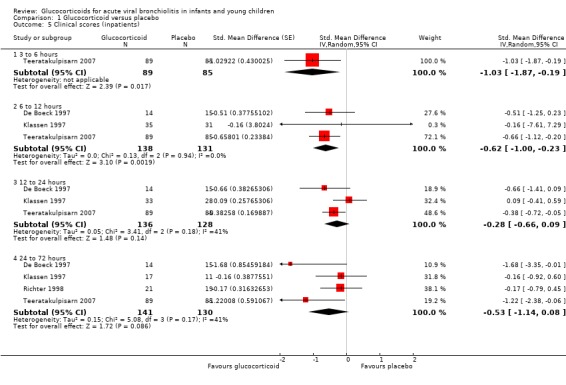

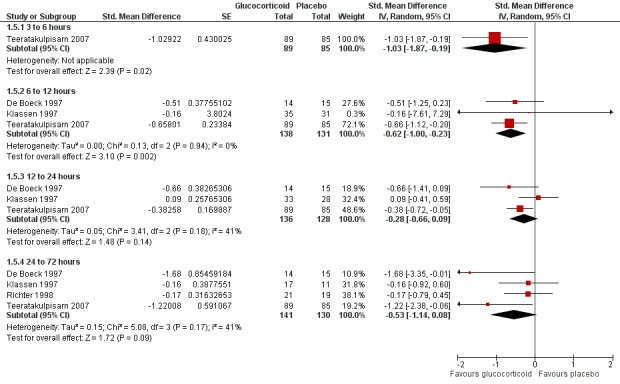

Clinical score data were only available for intervals between three to six hours and 24 to 72 hours (Analysis 1.5; Figure 9). Glucocorticoids were favoured at earlier time points (three to six hours, one trial, 174 participants: SMD ‐1.03 (95% CI ‐1.87 to ‐0.19); and 6 to 12 hours, three trials, 269 participants: SMD ‐0.62 (95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.23). There were no statistically significant differences at later time points. We assessed the overall strength of evidence for these findings as low or moderate, due to imprecision and low or unknown consistency, often with considerable heterogeneity.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 5 Clinical scores (inpatients).

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, outcome: 1.6 Clinical scores (inpatients) (change from baseline data).

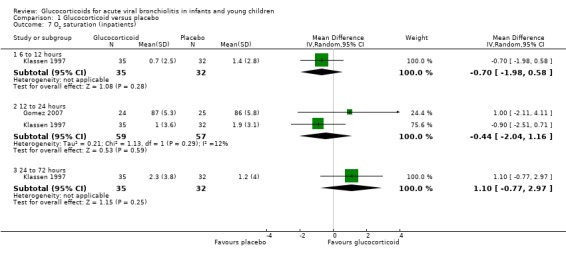

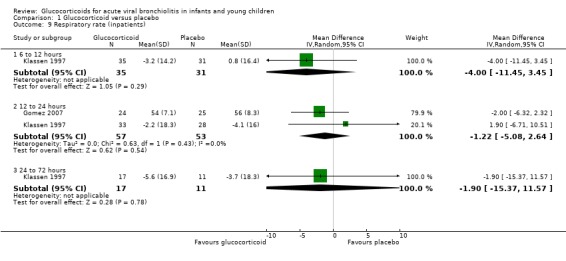

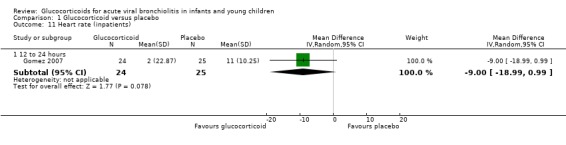

Only two trials reported outcomes of oxygen saturation and respiratory rate at time points between 6 to 12 hours and 24 to 72 hours, one of which also reported heart rate at 12 to 24 hours (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.11). There were no significant differences between groups for any outcome or time point.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 7 O2 saturation (inpatients).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 9 Respiratory rate (inpatients).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 11 Heart rate (inpatients).

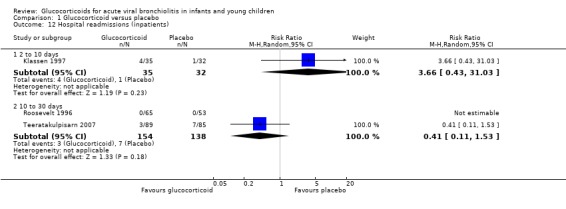

Both hospital re‐admissions and return healthcare visits were reported by three inpatient studies, with distinct durations of follow‐up; no significant differences were found between groups (Table 6; Analysis 1.12; Analysis 1.13).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 12 Hospital readmissions (inpatients).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glucocorticoid versus placebo, Outcome 13 Return healthcare visits (inpatients).

Three inpatient trials reported data on parent‐reported symptoms (Table 7). Different sets of symptoms were measured at distinct time points, and methods of measurement and analysis varied. In Teeratakulpisarn 2007 time to being symptom free was significantly shorter in the glucocorticoid group, while Cade 2000 used a different analysis and did not shown any statistically significant differences. There were no differences regarding respiratory symptoms and feeding in both Cade 2000 and Roosevelt 1996. No inpatient trials assessed or reported quality of life outcomes.

De Boeck 1997 reported results from pulmonary function tests on day three. No differences were found in minute ventilation, dynamic lung compliance, and inspiratory and expiratory pulmonary resistance, both before and after nebulised bronchodilator.

All patients

Adverse events

Six trials reported adverse events. Five assessed specific glucocorticoid‐related harms including the two largest studies (Table 8). We considered all harms data together regardless of patient setting in order to adequately assess the safety profile of glucocorticoids. Data were available from 600 to 1579 participants for each safety outcome. We did not pool results given the heterogeneity in definitions, methods and timings of assessment. Individual trial analysis did not show significant differences between glucocorticoids and placebo regarding the occurrence of vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, hypertension, pneumonia or varicella.

6. Harms ‐ adverse events.

| Adverse event | Number of participants | Study | Glucocorticoid‐including group, N (%) | Placebo or comparator group, N (%) | Notes | |

| GLUCOCORTICOID versus PLACEBO, GLUCOCORTICOID versus EPINEPHRINE, GLUCOCORTICOID AND EPINEPHRINE versus PLACEBO | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | Vomiting | 1466 | Plint 2009* | D + E: 2/199 (1) D + P: 5/199 (2.5) | P + E: 4/198 (2) P + P: 3/201 (1.5) | Observed in the emergency department by research nurse |

| Kuyucu 2004* | No events in either group (D + E, D + S, P + E, P + S) | Methods/timings NR | ||||

| Corneli 2007 | 16/305 (5.2) | 14/295 (4.7) | Within 20 minutes after administration of the study medication | |||

| Bleeding | 1576 | Corneli 2007 | No events in either group | # | ||

| Teeratakulpisarn 2007 | 2/90 (2) | 1/89 (1) | Occult blood; also assessed diarrhoea separately. Methods/timings NR | |||

| Plint 2009 | D + E: 17/199 (8.5) D + P: 12/199 (6) | P + E: 14/198 (7) P+P: 16/201 (8) | Dark stools; reported by families during the 22‐day telephone follow‐up. No patient had more than 1 episode | |||

| Endocrine | Hypertension | 1397 | Plint 2009 | D + E: 0/199 (0) D + P: 1/199 (0.5) | P + E: 1/198 (0.5) P + P: 0/201 (0) | Observed in infants admitted to hospital |

| Corneli 2007 | No events in either group | # | ||||

| Infectious | Pneumonia | 851 | Corneli 2007 | 1/305 (3.3) | 2/295 (7) | Also assessed empyema separately |

| Teeratakulpisarn 2007 | 0/90 (0) | 3/89 (3.4) | Methods/timings NR | |||

| Klassen 1997 | 1/35 (3) | 1/37 (3) | Methods/timings NR | |||

| Varicella | 1397 | Corneli 2007 | No events in either group | # | ||

| Plint 2009 | No events in either group | Reported by families during the 22‐day telephone follow‐up | ||||

| General | Tremor | 866 | Kuyucu 2004 | No events in either group | Methods/timings NR | |

| Plint 2009 | D + E: 4/199 (2) D + P: 5/199 (2.5) | P + E: 4/198 (2) P + P: 2/201 (1) | Observed in the emergency department by research nurse | |||

| Pallor/flushing | 866 | Kuyucu 2004 | No events in either group | Methods/timings NR | ||

| Plint 2009 | D + E: 23/199 (11.5) D + P: 15/199 (7.5) | P + E: 22/198 (11.1) P + P: 16/201 (8) | Observed in the emergency department by research nurse | |||

Additional reported adverse events: Goebel 2000 reported toxicity data: one patient was "jittery"; no evidence of further treatment complications. Plint 2009 also reported hyperkalaemia observed in infants admitted to hospital (only one case was noted in the dexamethasone group).

*epinephrine ‐ E; dexamethasone ‐ D; salbutamol ‐ S; placebo ‐ P

#Corneli 2007: Study clinicians and research assistants monitored the infants for adverse events during observation in the emergency department. Subsequent adverse events were determined at follow‐up. A patient safety committee, made up of people not involved with patient enrolment, tracked all adverse events.

Glucocorticoid and bronchodilator (epinephrine or salbutamol) versus placebo

Both outpatient trials assessing either of these comparisons used different severity thresholds for patient inclusion: Respiratory Distress Assessment Instrument (RDAI) score above four in Plint 2009 (moderate disease), and scores between 4 and 10 using a trial‐specific clinical scale in Barlas 1998 (mild to moderate disease).

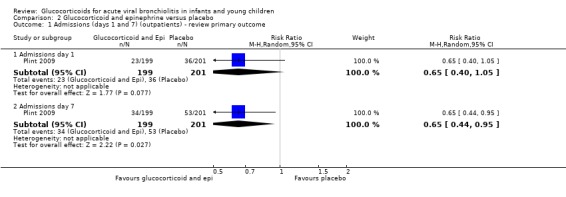

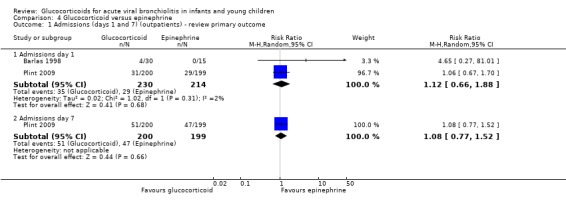

Primary outcomes

The factorial trial Plint 2009 included a comparison of oral dexamethasone and nebulised epinephrine against double placebo (399 analysed participants). This was the largest trial included in the review, with low overall risk of bias. The RRs for admissions by days 1 and 7 were 0.65 (95% CI 0.40 to 1.05) and 0.65 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.95), respectively (Analysis 2.1). There was a statistically significant reduction in admissions by day 7, with a relative risk reduction estimate of 35%. Absolute risk reduction was 9% (95% CI 1 to 17), and the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) to reduce one admission by day 7 was 11 (95% CI 7 to 76); these results were obtained through unadjusted analysis. However, the factorial trial design requires special methodological considerations, since this was not the study's main comparison, and there was an unanticipated additive/synergistic effect between epinephrine and dexamethasone. Reported analyses adjusted for multiple comparisons were above the threshold for statistical significance (RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.41 to 1.03). We graded the overall strength of evidence as low for these results given their imprecision and the fact that they were obtained from a single trial (Table 5; Table 2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Admissions (days 1 and 7) (outpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

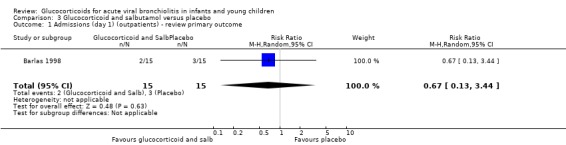

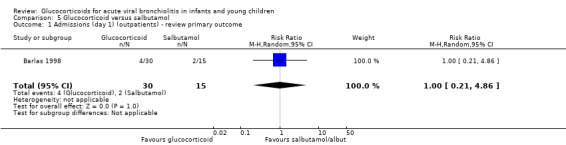

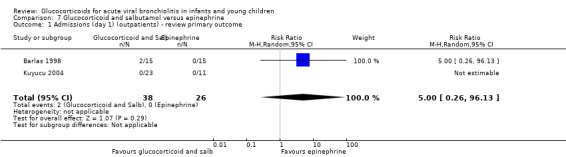

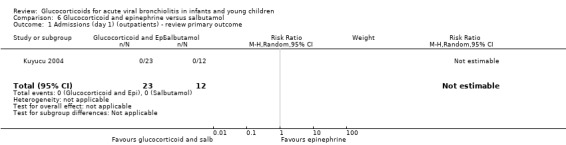

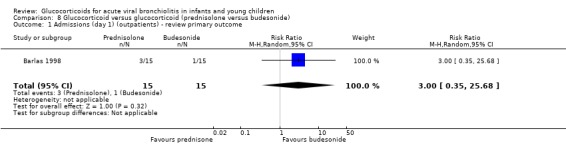

Barlas 1998, a small high risk of bias trial, compared intravenous prednisolone and nebulised salbutamol versus placebo. Admissions by day 1 (30 participants) showed no statistically significant differences between groups (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.13 to 3.44) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glucocorticoid and salbutamol versus placebo, Outcome 1 Admissions (day 1) (outpatients) ‐ review primary outcome.

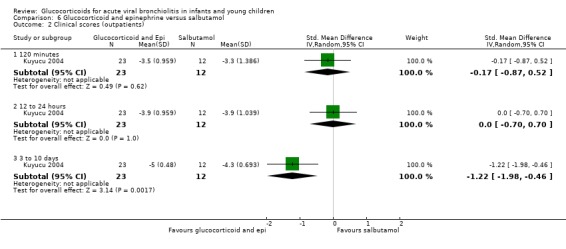

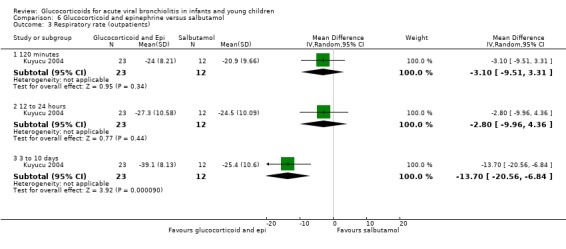

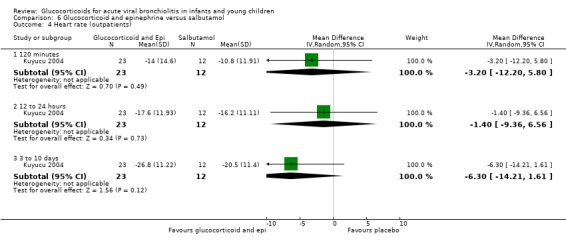

Secondary outcomes

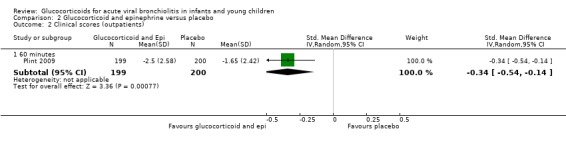

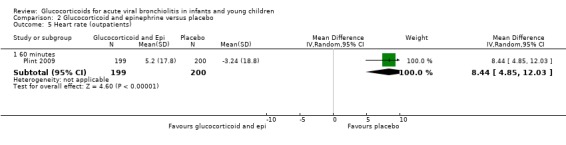

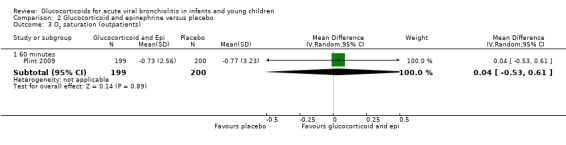

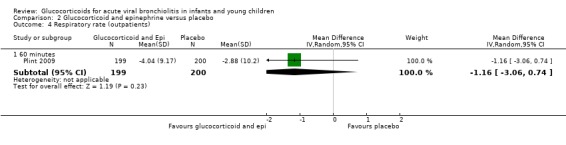

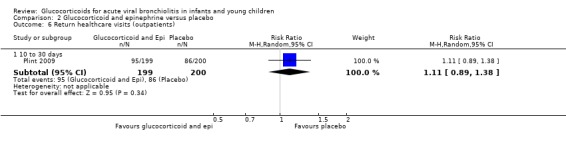

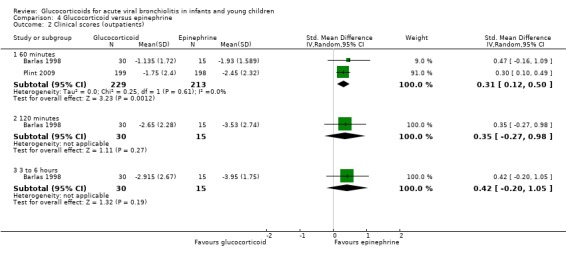

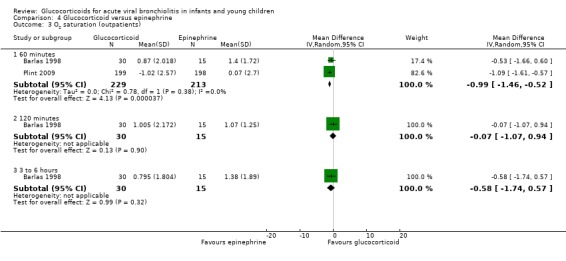

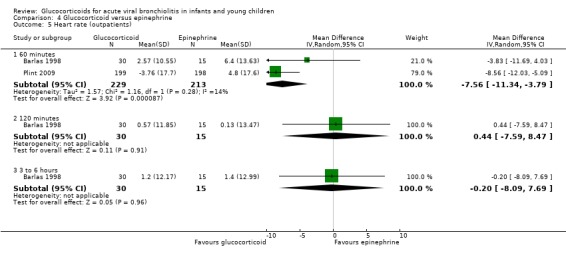

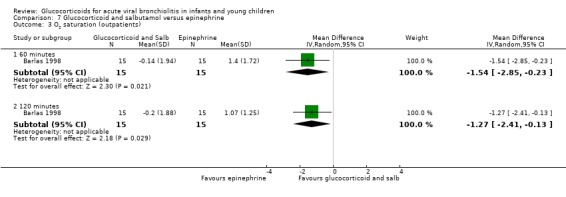

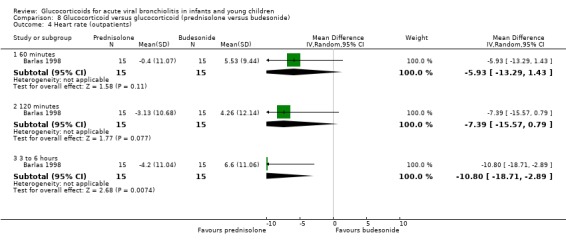

Clinical score results at 60 minutes favoured glucocorticoid and epinephrine (SMD ‐0.34; 95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.14) (Analysis 2.2), while having an increased heart rate (MD 8.44; 95% CI 4.85 to 12.03) (Analysis 2.5). No differences were found between groups regarding oxygen saturation and respiratory rate (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). There were also no differences regarding return healthcare visits for bronchiolitis symptoms (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.38) (Table 6; Analysis 2.6). Symptom results showed reduced time to normal feeding and quiet breathing in the glucocorticoid and epinephrine group (mean symptom duration ratios: 0.63; 95% CI 0.5 to 0.8 and 0.83; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) (Table 7). No differences were found in time to normal sleeping and time to no coughing.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Clinical scores (outpatients).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Heart rate (outpatients).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo, Outcome 3 O2 saturation (outpatients).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Respiratory rate (outpatients).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glucocorticoid and epinephrine versus placebo, Outcome 6 Return healthcare visits (outpatients).

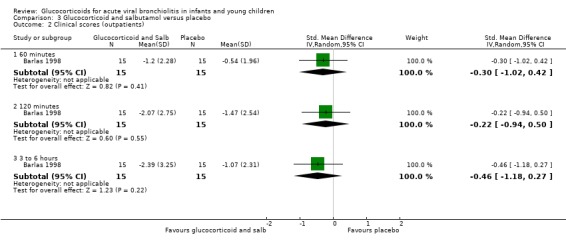

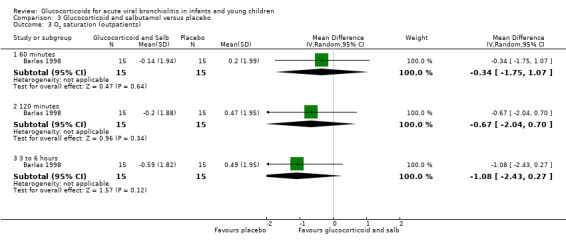

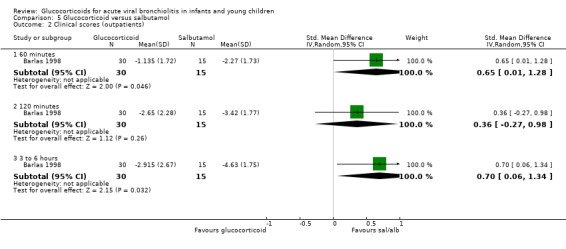

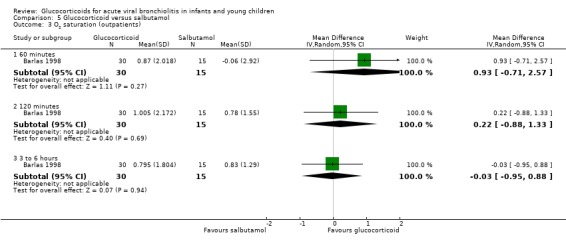

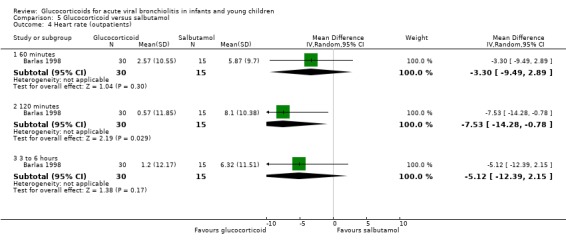

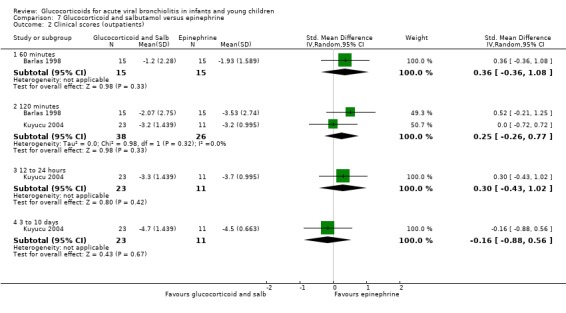

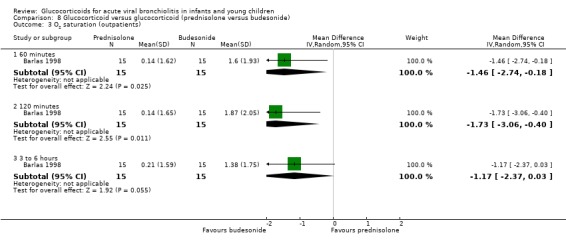

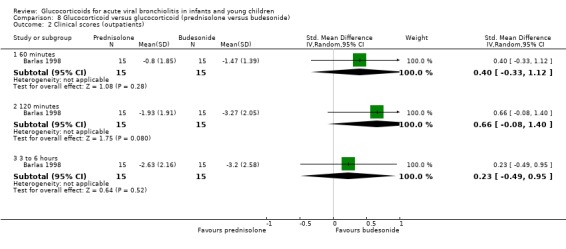

Results for clinical scores, oxygen saturation and heart rate at 60 minutes, 120 minutes and three to six hours did not show any differences between groups in the single trial comparing glucocorticoid and salbutamol versus placebo (Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4). No further secondary outcomes were assessed in this comparison.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glucocorticoid and salbutamol versus placebo, Outcome 2 Clinical scores (outpatients).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glucocorticoid and salbutamol versus placebo, Outcome 3 O2 saturation (outpatients).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Glucocorticoid and salbutamol versus placebo, Outcome 4 Heart rate (outpatients).

Other comparisons