Abstract

Background

Hypochondriasis is associated with significant medical morbidity and high health resource use. Recent studies have examined the treatment of hypochondriasis using various forms of psychotherapy.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness and comparative effectiveness of any form of psychotherapy for the treatment of hypochondriasis.

Search methods

1. CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References were searched on 7/8/2007, CENTRAL, Medline, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Cinahl, ISI Web of Knowledge, AMED and WorldCat Dissertations; Current Controlled Trials meta‐register (mRCT), CenterWatch, NHS National Research Register and clinicaltrials.gov; 2. Communication with authors of relevant studies and other clinicians in the field; 3. Handsearching reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles, and electronic citation search in ISI Web of Knowledge for all included studies.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled studies, both published and unpublished, in any language, in which adults with hypochondriasis were treated with a psychological intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted independently by two authors using a standardised extraction sheet. Study quality was assessed independently by the two authors qualitatively and using a standardised scale. Meta‐analyses were performed using RevMan software. Standardised or weighted mean differences were used to pool data for continuous outcomes and odds ratios were used to pool data for dichotomous outcomes, together with 95% confidence intervals.

Main results

Six studies were included, with a total of 440 participants. The interventions examined were cognitive therapy (CT), behavioural therapy (BT), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural stress management (BSM) and psychoeducation. All forms of psychotherapy except psychoeducation showed a significant improvement in hypochondriacal symptoms compared to waiting list control (SMD (random) [95% CI] = ‐0.86 [‐1.25 to ‐0.46]). For some therapies, significant improvements were found in the secondary outcomes of general functioning (CBT), resource use (psychoeducation), anxiety (CT, BSM), depression (CT, BSM) and physical symptoms (CBT). These secondary outcome findings were based on smaller numbers of participants and there was significant heterogeneity between studies.

Authors' conclusions

Cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural stress management are effective in reducing symptoms of hypochondriasis. However, studies included in the review used small numbers of participants and do not allow estimation of effect size, comparison between different types of psychotherapy or whether people are "cured". Most long‐term outcome data were uncontrolled. Further studies should make use of validated rating scales, assess treatment acceptability and effect on resource use, and determine the active ingredients and nonspecific factors that are important in psychotherapy for hypochondriasis.

Plain language summary

Psychotherapies for hypochondriasis

Hypochondriasis is a condition in which the sufferer believes or fears that they have an undiagnosed serious illness. It can cause much anxiety and repeated seeking of medical help and traditionally has been considered difficult to treat. A number of different psychotherapies have been suggested as treatments for sufferers of hypochondriasis, some of which have been tested in clinical trials.

The objective of this review was to assess whether any form of psychotherapy is effective in the management of people suffering from hypochondriasis. Six studies were included in the review. Analysis of data suggested that, compared to being on a waiting list, forms of cognitive and behaviour therapy, or a non‐specific therapy called behavioural stress management all improve the symptoms of hypochondriasis. However, the numbers of people in the studies were small and it was not possible to tell how much of an improvement each therapy made. It is possible that the improvements seen were due to non‐specific factors involved in regular contact with a therapist rather than specific properties of these forms of psychotherapy. It was also not possible to make comparisons between the different types of psychotherapy. A study of psychoeducation was not considered to be sufficient evidence that this form of psychotherapy is effective.

Background

Hypochondriasis is defined as a disorder in which there is excessive concern for one's own health. This is coupled with the belief that one has an undiagnosed physical illness, that persists despite adequate reassurance from medical staff. At present hypochondriasis is classified amongst the somatoform disorders, although its validity as a separate psychiatric entity has been questioned (Mayou 2003; Creed 2004). As excessive health anxiety lies at the heart of the disorder, there have been suggestions that hypochondriasis would be better classified as an anxiety disorder (Noyes 1999), whilst others have argued that it shares important similarities with the personality disorders (Tyrer 1990). Both the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (WHO 1992) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th Edition (APA 2000) outline operationalised criteria for the diagnosis of hypochondriasis. DSM‐IV specifies a minimum duration of symptoms of six months, while ICD‐10 does not specify duration. Some researchers maintain that both sets of criteria are unduly strict and have therefore suggested revised (or abridged) criteria that do not insist on the persistent refusal to accept medical reassurance (Gureje 1997). Despite this disagreement amongst psychiatrists over how best to classify hypochondriasis, it remains a distressing disorder for affected patients and an under‐recognised, costly and difficult disorder for physicians to contend with.

General population and primary care studies estimate the prevalence of hypochondriasis to be between 0.02% and 8.5%, with the population prevalence increasing to as much as 10.7% when abridged criteria are used (Creed 2004). Hypochondriasis is probably equally common amongst men and women and is associated with significant disability and high health costs (Creed 2004). A study examining the relationship with age found no association (Barsky 1991). Some studies have found an association with fewer years of education, while others have not (Creed 2004). Evidence also suggests that hypochondriasis is probably a relatively persistent condition over time (Barsky 1998); the co‐existence of anxiety and/or depression is common and is associated with chronicity of the disorder (Simon 2001).

Typically individuals with hypochondriasis present to doctors requesting investigation and reassurance, but find it difficult to be effectively reassured. This may lead to frequent presentations to primary and secondary care physicians, who find them particularly difficult to manage (Barsky 2001). For these reasons, people with hypochondriasis are not only costly to medical services but may interact with doctors in a manner that ultimately exacerbates their symptoms and distress. A number of different psychological models have been proposed for the aetiology of hypochondriasis. Psychodynamic writers have conceptualised the disorder either as an alternative channel for the individual's unacceptable sexual or aggressive drives, or as a defence mechanism against unbearably low self‐esteem. These models postulate that the hypochondriacal position is maintained by the primary gain of a reduction in intrapsychic conflict and the secondary gains associated with legitimately assuming the sick role (Barsky 1983). The cognitive behavioural model emphasises the role of excessive attention to and misinterpretation of benign bodily sensations, and suggests that repeated attempts to gain reassurance represents a form of avoidance behaviour, which leads to a temporary relief of anxiety only to be followed by an increase in the need for reassurance (Warwick 1990). In common with other anxiety and somatoform disorders, cognitive behavioural therapy has been suggested to be a potentially effective treatment modality for hypochondriasis, by challenging dysfunctional assumptions about illness and modifying behaviours of avoidance and reassurance‐seeking. A psychoeducational approach involving explanation of the cognitive behavioural model has also been proposed (Barsky 1998). Other forms of psychotherapy based on theories of psychodynamic or interpersonal conflict could potentially be useful. A variety of psychotropic medications, including antidepressants, benzodiazepines and antipsychotics have been used (Barsky 2001, Ikenouchi 2004, Lorenzo 2004). There is also a case report of the use of electro‐convulsive therapy (ECT) (Newmark 2004). An exploratory study found that patients with hypochondriasis considered cognitive behavioural therapy to be more acceptable and more effective than medication (Walker 1999). However, there is little clear guidance for clinicians on how best to treat people with hypochondriasis (Barsky 2001). A first step towards providing this guidance is to critically assess the results of relevant treatment trials. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the available evidence on the effectiveness of psychotherapies in the treatment of hypochondriasis.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of psychotherapies for adults with a primary diagnosis of hypochondriasis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled studies, both published and unpublished, were included. Trials which used cluster randomisation were included. Trials published in any language were considered.

Types of participants

Trials of adult men and women (aged between 18 and 75) with an ICD‐10 (WHO 1992), DSM‐IV (APA 2000) or abridged or equivalent diagnosis of hypochondriasis were included.

Studies were excluded if participants had a co‐morbid diagnosis of psychosis or a primary diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder (DSM‐IV excludes people who have delusional disorder or body dysmorphic disorder, while ICD‐10 excludes people with schizophrenia). Trials in which other conditions (e.g. depression, panic) were present were included provided the primary diagnosis was hypochondriasis. Physical co‐morbidity was not an exclusion criterion.

Types of interventions

All trials which included group or individual therapy, delivered as an out‐patient, in‐patient or in primary care, were included.

Active treatment The following types of psychotherapy were included: 1) Cognitive therapy ‐ therapy that focuses on modifying a person's present thinking, beliefs and attitudes towards illness 2) Behavioural therapy ‐ therapy that focuses on altering a person's present behavioural responses 3) Cognitive behavioural therapy ‐ therapy that attempts to modify present thinking, beliefs, attitudes and behavioural responses 4) Interpersonal therapy ‐ therapy that focuses on a person's relationships with peers and family members 5) Brief psychodynamic therapy ‐ therapy that explores unconscious meaning behind a person's symptoms 6) Hypnotherapy ‐ therapy based on the use of hypnosis 7) Counselling ‐ non‐directive psychotherapy in which the person is encouraged to express themselves in a non‐judgemental environment 8) Relaxation training ‐ general training in relaxation techniques 9) Psychoeducation ‐ therapy in which the main focus is the provision of information about the person's condition.

Psychotherapy categories Where studies were available, comparisons between psychotherapy approaches were also to be conducted, categorised as: 1) Cognitive behavioural therapy (cognitive, behavioural, cognitive‐behavioural, relaxation, psychoeducation) 2) Interpersonal therapy 3) Brief psychodynamic therapy 4) Other psychotherapies (eg counselling, hypnotherapy).

Trials were only included if treatment consisted of no more than 30 sessions, as only treatments that are practicably deliverable were to be assessed. Trials that combined psychotherapy with drug treatment as part of the study protocol were not included.

Control condition Only trials with a specified control condition were included. The following were considered to be control conditions: 1) No treatment 2) Treatment as usual 3) Waiting list 4) Placebo treatment (e.g. tablet placebo).

Treatment Comparisons Where studies were available the following main comparisons were made: 1) All forms of psychotherapy versus control 2) Cognitive therapy versus control 3) Behavioural therapy versus control 4) Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control 5) Interpersonal therapy versus control 6) Brief psychodynamic therapy versus control 7) Hypnotherapy versus control 8) Counselling versus control 9) Relaxation training versus control 10) Psychoeducation versus control

Additional comparisons Where studies become available, additional comparisons between categories of psychotherapy will be conducted (eg interpersonal therapy versus brief psychodynamic therapy)

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures The primary outcome was considered to be a reduction in hypochondriacal cognitions or behaviours, as measured by a hypochondriasis or health anxiety rating scale. If a validated scale was used, this was considered the primary outcome. Where visual analogue scales or unvalidated scales were used, the authors made a decision about which scale most closely approximated the symptoms of hypochondriasis.

Validated hypochondriasis and health anxiety scales considered for the purposes of this review were: 1) Health Anxiety Inventory (Salkovskis 2002) 2) Health Anxiety Questionnaire (Lucock 1996) 3) Somatic Symptom Index (Barsky 1990, Weinstein 1989) 4) Whitely Index (Pilowsky 1967; Speckens 1996) 5) Illness Attitudes Scale (Kellner 1987).

Secondary outcome measures The following secondary outcomes of trials were also assessed: 1) General functioning ‐ either i) clinician‐rated, e.g. Karnofsky index (Karnofsky 1948) or ii) patient‐rated, e.g. Short Form 36 (SF‐36) questionnaire (Jenkinson 1996) 2) Health services resource use ‐ eg. primary or secondary care consultation rate, secondary care referral rate, use of alternative practitioners 3) Psychological distress ‐ as measured by a validated scale for rating anxiety or depression e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1979), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton 1960), Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery 1979), Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck 1988), or Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton 1959) 4) Physical distress ‐ as measured by symptom scores, e.g. the Rating Scale for Somatic Symptoms (Kellner 1988) or the Somatic Symptom Inventory (Weinstein 1989) 5) Acceptability to participant, as measured by self‐report ratings of treatment acceptability 6) Drop out rates.

Outcomes were classified as assessed i) within one month post treatment ii) one to six months post treatment iii) greater than six months post treatment

Search methods for identification of studies

The following sources were used to identify potential studies for inclusion in this review:

Electronic searches 1) CCDANCTR‐Studies was searched on 7/8/2007 using the search terms Intervention = Hypochondriasis or "Health Anxiety"

CCDANCTR‐References was searched on 7/8/2007 using the search terms Free‐text = Hypochondria* or "health anxiety"

2) CENTRAL was searched using the search terms hypochondri$, health anxiety, Psychotherapy, cognitive therap$, behavi$ therap$, cognitive behavi$ therap$, interpersonal therap$, psychodynamic, psychoanal$, hypno$, counsel$, explanatory therap$, group therap$, family therap$, stress management, exposure response prevention, psychoeducation;

3) MEDLINE, PSYCinfo, Embase, AMED and Cinahl were searched using the CCDAN search strategy and the additional search terms hypochondri$, health anxiety, Psychotherapy, cognitive therap$, behavi$ therap$, cognitive behavi$ therap$, interpersonal therap$, psychodynamic, psychoanal$, hypno$, counsel$, explanatory therap$, group therap$, family therap$, stress management, exposure response prevention, psychoeducation;

4) ISI Web of Knowledge was searched using the search terms hypochondria*, health anxiety, Psychotherapy, cognitive therap*, behavi* therap*, cognitive behavi* therap*, interpersonal therap*, psychodynamic, psychoanal*, hypno*, counsel*, explanatory therap*, group therap*, family therap*, stress management, exposure response prevention, psychoeducation

For each included study, a cited reference search was performed in ISI Web of Knowledge to identify any later studies that may have cited it as a reference.

5) WorldCat Dissertations was searched using the search terms hypochondriasis, health anxiety.

Personal communication Experts in the field were contacted and asked to identify other published and unpublished trials.

Reference lists The reference lists of retrieved studies and relevant review articles were reviewed to identify any other studies.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection Abstracts of potentially relevant studies were inspected by the review authors and full articles requested where there was an indication that they might be relevant. Where unpublished trials were identified, the co‐ordinators were contacted to request the data. Full papers were then inspected independently by the review authors to assess whether studies fulfilled criteria for inclusion in this review. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or use of a third opinion.

Quality assessment Methodological quality was assessed independently by both review authors according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2006). This was in the form of a qualitative assessment for the presence of bias under the following categories: 1) Selection bias 2) Performance bias 3) Attrition bias 4) Detection bias.

The presence of each category of bias was assessed as being likely, possible, unlikely or unclear. An additional quality assessment was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration Depression and Anxiety Group Quality Rating Scale (QRS) (Moncrieff 2001). The QRS consists of 23 items, including items on sample size, allocation, use of diagnostic criteria, compliance, attrition and statistical analysis. Total scores range from 0‐46. Quality rating scores were used for descriptive purposes and to categorise studies into high and low quality, for sensitivity analyses. Any disagreements between authors were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction Data from identified trials were independently extracted by the review authors using a standardised extraction sheet. Any disagreements were discussed. Where data were missing from the published studies, attempts were made to obtain this by correspondence with the trial authors. Information extracted included the characteristics of the study, design and methods used, number and characteristics of participants, nature of intervention, nature of control, outcomes and results. Results were entered into an Excel spreadsheet then transferred into Review Manager software (RevMan) for analysis. Accuracy of data entry was checked by using the double data entry feature.

Analysis Where appropriate, outcome data were pooled using RevMan software. Dichotomous data such as dropout rates were pooled using odds ratios. Where ordinal rating scales were used, results were treated as continuous data. Continuous data were pooled using weighted mean differences where outcomes were measured using the same validated rating scales, or by using standardised mean differences where outcomes are measured on different or unvalidated rating scales. All outcome data other than dropout rates was either in the form of long ordinal scales or continuous visual analogue scales and so were treated as continuous data. Where studies did not use intention‐to‐treat analyses, an available case analysis was used.

Studies were assessed for heterogeneity using both the chi‐squared and the I‐squared tests. Forest plots were also visually inspected to assess for heterogeneity. Given the small number of studies and the heterogeneity between them, random‐effects models were used to pool outcome data (Field 2003). If a primary outcome was not stated in the study, the review authors agreed by discussion on an outcome measure to use as the primary outcome.

Results from all the studies were pooled in a meta‐analysis of all forms of psychotherapy. In order to avoid making multiple comparisons with the same control group, where studies had more than one treatment arm, data from both treatment arms were combined. Dichotomous outcomes were combined by taking the sums of the number of events (e.g. dropouts) and the number of participants in both active treatment arms. The means of continuous data were combined using the formula shown in Figure 1.The combined standard deviations of continuous data were obtained using the formula shown in Figure 2 (Cooper 1994). The combined means and standard deviations for the two active treatment arms were then compared to the control outcome data for each trial.

1.

2.

Where studies used a cluster randomisation design, it was planned to divide the original sample size by the design effect, calculated from the average cluster size and the intracluster correlation coefficient (Higgins 2006), where deemed necessary.

Subgroup analyses were defined a priori and carried out as follows: 1) By differing diagnostic criteria 2) By validated versus unvalidated scales for hypochondriasis 3) By total psychotherapy exposure time (<8h versus >8h).

A sensitivity analysis was performed as follows: 1) Comparing high and low quality studies, based on QRS scores of equal or less than 25 and greater than 25 2) By including all studies in the meta‐analysis regardless of the time point of the outcome measures.

The construction of funnel plots to assess for publication bias was considered, but there were not sufficient studies included in this review.

Methods for updating the review This is the first published version of this review. We will review the protocol and repeat the search strategy every two years. If additional studies are identified for inclusion then the review will be updated. Additionally, if the authors become aware of studies that should be included in the review, then the search strategy will be repeated and the review updated.

Results

Description of studies

Thirty‐seven studies were identified. Six were included and 26 excluded. Of the remainder two are ongoing and three are awaiting assessment. There were no disagreements between review authors regarding study inclusion. See tables of Characteristics of Excluded Studies and Included Studies.

Excluded Studies Twenty published studies did not meet inclusion criteria. Of these, 12 studies did not use a randomised design (Avia 1996; Bouman 2002; Kellner 1982; Kellner 1983; Kenyon 1964; Langlois 2004; Martinez 2005; Papageorgiou 1998; Stern 1991; Visser 1992; Warwick 1988; Wattar 2005); three studies did not use standard diagnostic criteria for hypochondriasis (Jones 2002; Kellner 1971; Tyrer 1999) and three studies were case series (Brown 1936; Salkovskis 1986; Townend 1994). Two studies randomly allocated participants to two different arms of therapy but did not include a control condition (Bouman 1998; Buwalda 2006).

Five PhD or MA theses did not meet inclusion criteria. Four were uncontrolled studies (Anderson 1996; Fried 1978; Hassan 1989; Schmieschek 1968). One was a case report (Rhinard 1967).

One reference to an unpublished trial was found (Salkovskis 2001). The co‐ordinators confirmed that this trial had been registered but not completed.

Ongoing studies Two studies are ongoing (Jones 2006; Nolido 2006). Three studies are awaiting assessment (Cavanagh 2004; Salkovskis 2006 b; Sorenson 2004), and will be considered for inclusion in an updated version of the review.

Included Studies Six studies were identified for inclusion in this review (Barsky 2004; Clark 1998 a; Fava 2000 b; Greeven 2004; Visser 2001; Warwick 1996). All were published in English language journals.

Description of Study Design All included studies were randomised controlled trials. One study used a cluster randomised design (Barsky 2004), whereby primary care physicians were randomised to determine whether participants received CBT or treatment as usual. Only 11 out of 163 physicians in the trial had more that one participant. A sensitivity analysis of the potential effect of clustering was reported in the paper, in which an analysis using only one subject selected at random from each of the clusters (excluding 24 participants) was compared to an analysis using data from all participants. The results did not differ. Therefore, the effect of clustering in this study was not considered significant. Four studies used designs in which a proportion of subjects were initially placed on a waiting list and later entered into therapy (Clark 1998 a; Fava 2000 b; Visser 2001; Warwick 1996). One of these studies (Clark 1998 a) reported combined post‐treatment outcomes for the initial intervention group plus the later group that had originally been part of the control group. Therefore, comparison of these outcomes to the control group partly involved between‐groups comparison and partly a within‐group comparison. Since within‐group comparison potentially provides a more precise estimate (Senn 2002), the data were handled conservatively by treating them as for a between‐groups comparison, for the purposes of meta‐analysis.

Participants One study recruited subjects exclusively from secondary care (Fava 2000 b), whilst two studies recruited from both primary and secondary care (Clark 1998 a; Warwick 1996). One study recruited from primary care and also used volunteer subjects who responded to public announcements (Barsky 2004). One study recruited from secondary care and also used volunteer subjects who responded to public announcements (Greeven 2004). One study did not state from where subjects were recruited (Visser 2001).

Three studies included subjects who fulfilled DSM‐IV criteria for hypochondriasis (Fava 2000 b; Greeven 2004; Visser 2001), whilst two studies used DSM‐IIIR criteria (Clark 1998 a; Warwick 1996). One study used a predetermined cut‐off on a combined Whitely Index and Somatic Symptom Inventory (Barsky 2004), with 61% of participants fulfilling DSM‐IV criteria.

All studies excluded subjects with serious psychiatric co‐morbidity (e.g. psychosis). Only one study (Visser 2001) did not exclude subjects who had significant medical co‐morbidity, although the other studies defined this exclusion criterion in different ways. Two studies excluded those that had received CBT previously (Visser 2001; Warwick 1996).

Cultural Setting Two studies were set in the United Kingdom (Warwick 1996; Clark 1998 a), two studies in the Netherlands (Greeven 2004; Visser 2001), one study in the United States (Barsky 2004) and one study in Italy (Fava 2000 b).

Sample Size The number of subjects randomised into the studies varied from 20 (Fava 2000 b) to 187 (Barsky 2004).

Interventions The active intervention in all six trials was individual (one to one) therapy delivered in an outpatient setting. Three studies used CBT (Barsky 2004; Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996), two studies used CT (Visser 2001; Clark 1998 a), one study used explanatory therapy (Fava 2000 b); one study used exposure plus response prevention (which was classified as behavioural therapy for the purposes of this study) (Visser 2001) and one study used behavioural stress management (Clark 1998 a).

Explanatory therapy (Fava 2000 b) is described as providing patient education, reassurance and teaching of the principles of selective attention ‐ it is said to differ from CBT in that it is simpler to deliver and does not contain behavioural components. For the purposes of this review explanatory therapy was classified as psychoeducation.

Behavioural stress management combined elements of relaxation, problem‐solving, assertiveness training and time management. It was developed as an alternative to cognitive behavioural therapy with the aim of addressing the anxious and avoidant aspects of hypochondriasis. Although this did not fit into any predefined category of psychotherapy, it seemed sufficiently different to be considered as a separate form of therapy.

Three studies had one active treatment and one control arm (Barsky 2004; Fava 2000 b; Warwick 1996). Two studies had two active treatment arms, both psychotherapy, and one control arm (Clark 1998 a; Visser 2001). One study had two active treatment arms ‐ one psychotherapy and one medication arm ‐ and a control arm (Greeven 2004). Amount of therapy time in the active arm varied from four hours (Fava 2000 b) to 19 hours (Clark 1998 a). Four studies used waiting list controls (Visser 2001; Warwick 1996; Fava 2000 b; Clark 1998 a), one allocated controls to receive treatment as usual from their primary care physician (Barsky 2004) and one used placebo tablets plus medication review appointments (Greeven 2004).

Outcome measures A wide range of outcome measures was used in the studies. All the studies used a measure of hypochondriacal cognitions and behaviours. Three studies did not specify a primary outcome measure (Clark 1998 a; Fava 2000 b; Warwick 1996). Of the three studies that did specify a primary outcome, two studies (Barsky 2004; Greeven 2004) used the Whiteley Index (Pilowsky 1967) and one study (Visser 2001) used the health anxiety subscale of the Illness Attitudes Scale (Kellner 1987). The Illness Attitudes Scale was also included in one study which did not specify a primary outcome (Fava 2000 b). Two studies (Clark 1998 a; Warwick 1996) did not use recognised hypochondriasis scales but instead used a number of visual analogue scales devised by the authors to assess different aspects of health anxiety. Table 12 gives details of the outcome measures selected for the analyses.

1.

Outcome measures used in the analyses

| Study | Therapies | Primary Outcome | General Functioning | Resource Use | Psychological Sx | Physical Sx |

| Barsky 2004 | CBT | Whitely Index (specified in paper) | FSQ ‐ intermediate activities of daily living subscale | SSI | ||

| Clark 1998 | CT; BSM | VAS ‐ health worry‐related distress‐disability ‐ self‐rated (selected by review authors) | BDI; BAI | |||

| Fava 2000 | ET | IAS ‐ hypochondriasis subscale (selected by review authors) | No. of visits to physicians in 3 month period | RSSS | ||

| Greeven 2007 | CBT | Whitely Index (specified in paper) | MADRS; BAS | |||

| Visser 2001 | CT; BT | IAS Health Anxiety subscale (specified in paper) | BDI | |||

| Warwick 1996 | CBT | VAS ‐ Health anxiety ‐ self‐rated (selected by review authors) | BDI; BAI |

Two studies included measures of physical distress: one study (Fava 2000 b) used the Rating Scale of Somatic Symptoms (Kellner 1988) and another (Barsky 2004) used the Somatic Symptom Inventory (Weinstein 1989).

Four studies included measures of psychiatric symptoms: two (Greeven 2004; Visser 2001) used the Dutch version of the SCL‐90 Symptom Checklist (Arrindell 1986; Derogatis 1973), three studies (Clark 1998 a; Visser 2001; Warwick 1996) used the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1979; Bouman 1985), one study (Greeven 2004) used the Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the Brief Anxiety Scale (Montgomery 1979; Tyrer 1984) two studies (Clark 1998 a; Warwick 1996) used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck 1988), and one study (Clark 1998 a) also used the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton 1959).

Only one study (Barsky 2004) assessed functional outcome, using the Functional Status Questionnaire (Cleary 2000; Jette 1986). One study (Fava 2000 b) assessed health service use by measuring the number of physician visits and laboratory tests over a 3‐month period.

All six studies provided data on the number of dropouts. No study measured the acceptability of the therapy to participants. Study Length Length of follow‐up varied from immediately post treatment only (Greeven 2004) to 12 months post treatment (Barsky 2004; Clark 1998 a). Only one study made comparisons between treatment and control at time points later than immediately post‐treatment (Barsky 2004).

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomisation method Only one study provided details of the method of randomisation, which was judged to be adequate (Greeven 2004). This study used block randomisation, in which an independent statistician prepared allocation information in sealed opaque envelopes that were opened when a participant was included in the study.

Allocation concealment Only two studies (Barsky 2004; Greeven 2004) described adequate allocation concealment, although one of these used cluster randomisation of physicians rather than participants. This could have resulted in a small number of participants (approximately 25 out of 187) failing to receive concealed allocation because their physician had already been randomised (Barsky 2004). None of the other included studies described allocation concealment; therefore the quality was judged to be 'unclear' on this validity criterion.

Blinding Blinding of participants is difficult to achieve in psychotherapeutic trials, since participants are aware of the type of therapy that they are receiving or whether they are on a waiting list. All studies used self‐report rating scales. One study (Warwick 1996) used participants' therapists to rate several measures; the therapists could not have been blinded and were therefore subject to observer bias. Four studies also used some scales rated by an independent assessor; three stated that the assessor was blinded (Fava 2000 b; Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996), and one did not specify (Clark 1998 a). Baseline characteristics No study reported significant differences in age or gender between treatment and control groups, although one study failed to report any sociodemographic comparisons (Clark 1998 a) and another reported only that no significant difference had been found (Warwick 1996). Of the three studies that presented comparisons of baseline characteristics (Barsky 2004; Fava 2000 b; Visser 2001), only two performed statistical tests for differences between groups (Barsky 2004; Greeven 2004).

Interventions One study did not include information on supervision or monitoring of the active intervention (Fava 2000 b). One study used manualised treatment (Barsky 2004) and four studies used tape recordings of the sessions to supervise and/or audit treatment (Clark 1998 a; Greeven 2004; Visser 2001; Warwick 1996).

One study may have introduced performance bias, as there was evidence of co‐intervention (Barsky 2004): a detailed letter of advice was sent to all primary care physicians whose patients were randomised to receive the active treatment. This meant that it was not possible to attribute any change to the psychotherapy (CBT) alone, as the letter could have significantly altered the GPs' management in the active group.

Studies that had two active psychotherapy arms (behavioural and cognitive) as well as a control arm (Clark 1998 a; Visser 2001) also showed some evidence of co‐intervention, as the cognitive therapy arms contained elements of behavioural therapy.

Dropouts All studies reported whether participants left the trial early for any reason. Dropout rates varied from 3.1% to 28.2%. Three studies used an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Barsky 2004; Fava 2000 b; Greeven 2004).

Selective reporting There was nothing in the papers to suggest selective reporting of outcome data. All studies presented all outcome data that had been described in the "methods" sections and included these data in the analyses. However, some studies did not include secondary outcome measures that had been included in other studies and the results reported were positive and generally statistically significant.

Quality Rating Scale scores Quality Rating Scale (Moncrieff 2001) scores ranged from 21 (Visser 2001) to 30 (Barsky 2004; Greeven 2004), mean score 25.8.

Effects of interventions

Although all studies reported follow‐up data, most studies were designed so that the waiting list groups were allocated to active therapy immediately after the first period of therapy and assessment ended. Therefore, they were only a parallel group design until the first post‐treatment assessment, after which they were uncontrolled trials. Only one trial (Barsky 2004) provided sufficient control data to enable treatment versus control comparisons to be made at later follow‐up points. All other comparisons were made immediately post treatment. Comparison 1: All forms of psychotherapy versus waiting list/usual medical care/tablet placebo Where possible, the outcome data from the five included studies that reported outcomes immediately post‐treatment, with a total of 247 participants, were pooled for most of the outcomes (Clark 1998 a; Fava 2000 b; Greeven 2004; Visser 2001; Warwick 1996). Data from the study which did not report outcomes immediately post‐treatment (Barsky 2004) were not pooled in this comparison. Where only one form of psychotherapy examined a secondary outcome, this is reported under the relevant section below.

01.01 Hypochondriasis The psychotherapy group did significantly better than the waiting list group (SMD (random) = ‐0.86 [95% CI ‐1.25 to ‐0.46]). There was significant heterogeneity between trials (chi‐squared = 7.65, p = 0.11, I‐squared =47.7%).

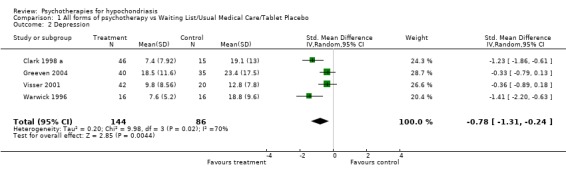

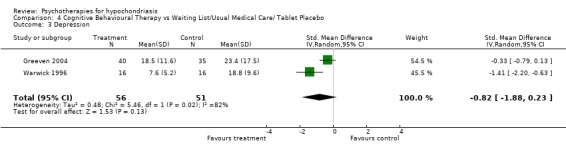

01.02 Depression Four studies with a total of 230 participants examined this outcome (Clark 1998 a; Greeven 2004; Visser 2001; Warwick 1996). The psychotherapy group did significantly better than the waiting list group (SMD (random) = ‐0.78 [95% CI ‐1.31 to ‐0.24]). There was significant heterogeneity between trials (chi‐squared = 9.98, p = 0.02, I‐squared = 69.9%).

01.03 Anxiety Three studies with a total of 164 participants examined this outcome (Clark 1998 a; Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996). The psychotherapy group did significantly better than the waiting list group (SMD (random) = ‐0.96 [95% CI ‐1.64 to ‐0.27]). There was significant heterogeneity between trials (chi‐squared = 7.32, p = 0.03, I‐squared = 72.7%).

01.04 Physical Symptoms Two studies with a total of 207 participants examined this outcome (Barsky 2004; Fava 2000 b). The psychotherapy group did significantly better than the waiting list group. (SMD (random) = ‐0.41 [95% CI ‐0.69 to ‐0.13]). There was not significant heterogeneity between trials (chi‐squared = 0.09, p = 0.77, I‐squared = 0%).

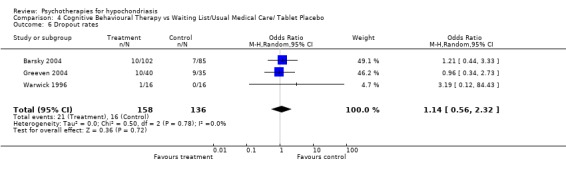

01.05 Dropout rates All five studies reported numbers of participants who left the trial early for any reason. There was no significant difference between treatment and control (OR (random) = 1.17 [95% CI 0.58 to 2.34]). There was not significant heterogeneity between trials (chi‐squared = 1.01, p = 0.91, I‐squared = 0%).

Comparison 2: Cognitive therapy versus waiting list Two studies with a total of 79 participants compared CT to a waiting list (Clark 1998 a; Visser 2001).

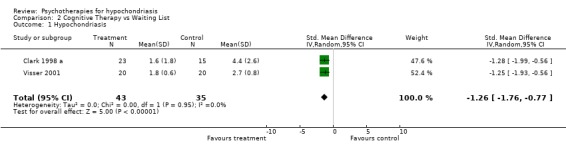

02.01 Hypochondriasis The CT group did significantly better than the waiting list group immediately after treatment (SMD (random) = ‐1.26 [95% CI ‐1.76 to ‐0.77]). There was no significant heterogeneity between the two trials (chi‐squared = 0.00, p = 0.95, I square = 0%).

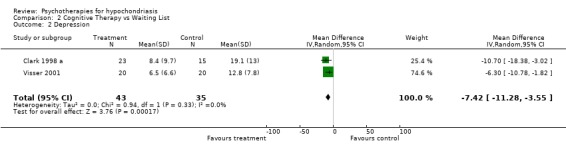

02.02 Depression The CT group did significantly better than the waiting list group immediately after treatment (WMD (random) = ‐7.42 [95% CI ‐11.28 to ‐3.55]). There was no significant heterogeneity between the two trials (chi‐squared = 0.94, p = 0.33, I‐squared = 0%).

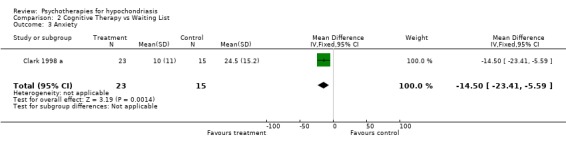

02.03 Anxiety One study (Clark 1998 a) examined this outcome. The CT group did significantly better than the waiting list group (WMD (fixed) [95% CI] = ‐14.50 [‐23.41 to ‐5.59]).

02.04 Dropout rates There was no significant difference in drop out rate between treatment and control (OR (random) = 1.089 [95% CI 0.33 to 3.52]). There was no significant heterogeneity between the two trials (chi‐squared = 0.43, p = 0.51, I‐squared= 0%).

02.05 Acceptability One study (Clark 1998 a) attempted to measure acceptability by asking participants the extent to which they thought their treatment was logical, would be successful and would recommend to a friend. They reported no significant difference when compared to ratings for behavioural stress management.

General functioning, resource use and physical distress were not measured in studies of cognitive therapy.

Comparison 3: Behavioural therapy versus waiting list One study with a total of 48 participants compared behavioural therapy (BT) to a waiting list (Visser 2001).

03.01 Hypochondriasis The BT group did significantly better than the waiting list group immediately after treatment (WMD (fixed) = ‐0.60 [95% CI ‐1.11 to ‐0.09]).

03.02 Depression There was no significant difference between treatment and waiting list immediately after treatment (WMD (fixed) = 0.30 [95% CI ‐5.10 to 5.70]).

03.03 Dropout rates There was no significant difference between treatment and waiting list (OR (fixed) = 0.93 [95% CI 0.26 to 3.29]).

General functioning, resource use, anxiety, physical distress and acceptability were not measured in studies of behavioural therapy. Comparison 4: Cognitive behavioural therapy versus waiting list/usual medical care/ tablet placebo Three studies compared cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to a waiting list, usual medical care or tablet placebo, with a total of 219 participants (Barsky 2004; Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996). Data were pooled separately for different follow‐up points. 04.01 Hypochondriasis Two studies reported outcomes immediately post‐treatment (Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996). The difference between the CBT group and the waiting list/placebo group failed to reach significance (SMD (random) = ‐0.80 [95% CI ‐1.62 to 0.01]. There was significant heterogeneity between the two trials (chi‐squared = 0.3.33, p = 0.07, I‐squared = 69.9%). In the study that examined outcomes at 12‐month follow‐up (Barsky 2004), the CBT group did significantly better (SMD (fixed) = ‐0.43 [95% CI ‐0.72 to ‐0.14]).

04.02 General functioning One study examined this outcome with a total of 187 participants (Barsky 2004). The CBT group did significantly better than the usual medical care group at 12‐month follow‐up (WMD (fixed) = 11.19 [95% CI 5.29 to 17.09]).

04.03 Depression Two studies examined this outcome with a total of 107 participants (Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996). The difference between CBT and waiting list/placebo was not significant (SMD (random) = ‐0.82 [95% CI ‐1.88 to 0.23]. There was significant heterogeneity between the two trials (chi‐squared = 5.46, p = 0.02, I‐squared = 81.7%). 04.04 Anxiety Two studies examined this outcome with a total of 103 participants (Greeven 2004; Warwick 1996). The difference between CBT and waiting list/placebo was not significant (SMD (random) = ‐0.79 [95% CI ‐1.70 to 0.12]. There was significant heterogeneity between the two trials (chi‐squared = 4.09, p = 0.04, I‐squared = 75.5%). 04.05 Physical symptoms One study examined this outcome with a total of 187 participants (Barsky 2004). The CBT group did significantly better than the usual medical care group at 12‐month follow‐up (WMD (fixed) = ‐0.24 [95% CI ‐0.40 to ‐0.08]).

04.06 Dropout rates All three studies recorded whether participants left the trial early for any reason. There was no significant difference between treatment and control (OR (random) = 1.15 [95% CI 0.56 to 2.32]). There was not significant heterogeneity between the trials (chi‐squared = 0.50, p = 0.78, I‐squared = 0%).

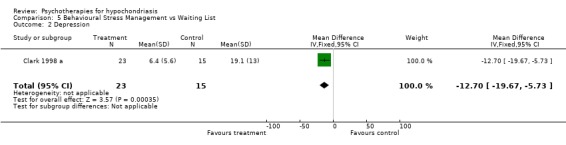

Resource use and acceptability were not measured in studies of cognitive behavioural therapy. Comparison 5: Behavioural stress management versus waiting List One study examined 32 participants, comparing behavioural stress management (BSM) to a waiting list (Clark 1998 a). . 05.01 Hypochondriasis The BSM group did significantly better than the waiting list group (WMD (fixed) = ‐2.40 [95% CI ‐3.87 to ‐0.93]). 05.02 Depression The BSM group did significantly better than the waiting list group (WMD (fixed) = ‐12.70 [95% CI ‐19.67 to ‐5.73]). 05.03 Anxiety The BSM group did significantly better than the waiting list group (WMD (fixed) = ‐14.90 [95% CI ‐23.21 to ‐6.59]). 05.04 Dropout rates There was no significant difference between the BSM group and waiting list group (OR (fixed) = 2.82 [95% CI 0.11 to 74.51]). 05.05 Acceptability One study (Clark 1998 a) attempted to measure acceptability by asking participants the extent to which they thought their treatment was logical, would be successful and would recommend to a friend. They reported no significant difference when behavioural stress management ratings were compared to ratings for cognitive therapy.

The study did not measure general functioning, resource use, physical distress or acceptability.

Comparison 6: Psychoeducation versus waiting list One study examined 20 participants, comparing psychoeducation to a waiting list (Fava 2000 b).

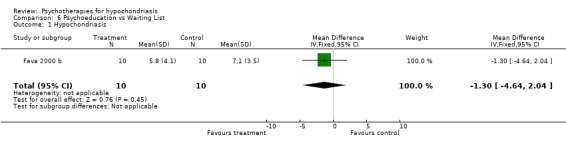

06.01 Hypochondriasis There was no significant difference between treatment and control groups (WMD (fixed) = ‐1.30 [95% CI ‐4.64 to 2.04]).

06.02 Resource use The Psycho‐education group used significantly fewer resources than the waiting list group (WMD (fixed) = ‐6.00 [95% CI ‐11.70 to ‐0.30]).

06.03 Physical symptoms There was no significant difference between treatment and control groups (WMD (fixed) = ‐2.20 [95% CI ‐8.73 to 4.33]). 06.04 Dropout rates There was no significant difference between treatment and control groups (OR (fixed) = 2.25 [95% CI 0.17 to 29.77]).

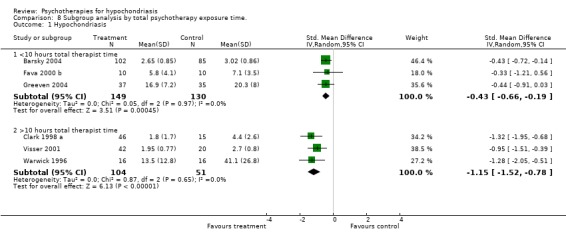

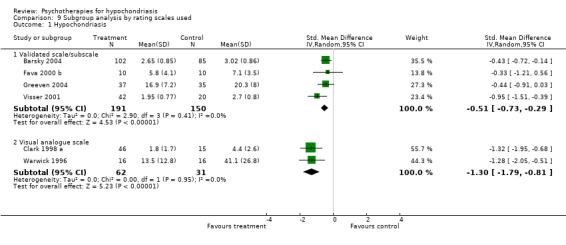

Subgroup analysis The effect size for hypochondriasis was largest in the studies that had the largest amount of therapist time, used visual analogue scales and used DSM‐IIIR diagnostic criteria. The difference was significant when the studies were grouped by therapist time (SMD (random) = ‐1.15 [95% CI ‐1.52 to ‐0.78] for >10h versus ‐0.43 [‐0.66 to ‐0.19] for <10h) or by type of scale used (SMD (random) = ‐1.30 [95% CI ‐1.79 to ‐0.81] for visual analogue scales versus ‐0.51 [‐0.73 to ‐0.29] for validated scales). The differences were not significant when studies were grouped by diagnostic criteria used. There was no significant heterogeneity within any of the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis Comparisons were made between studies which scored equal to or less than 25 or greater than 25 on the QRS. The difference between the two groups was not significant (SMD (random) = ‐1.06 [95% CI ‐1.52 to ‐0.61] for scores <25 versus ‐0.61 [‐0.99 to ‐0.22] for scores > 25). Significant heterogeneity was found in the group of studies with higher quality scores (chi‐squared = 6.73, p = 0.08, I‐squared = 55.4%).

The primary outcome measure of most studies was measured immediately post‐treatment. One study (Barsky 2004) measured outcomes at 12‐month follow‐up. The meta‐analysis of all forms of psychotherapy was repeated for the hypochondriasis outcome including this study to assess the effect of comparing outcomes from different time points. When this study was included, the psychotherapy group still did significantly better than the control group, with a slightly smaller effect size (SMD (random) = ‐0.75 [95% CI ‐1.09 to ‐0.41]).

Post hoc analysis In the subgroup analysis (figure 08.01) it was observed that studies that had a larger total amount of time with a therapist also had a larger effect size as measured by SMD. In order to explore this, a graph of effect size (SMD) was plotted against hours of therapist time (Figure 3). Where the length of each session was not stated in the paper, this was assumed to be one hour. The resulting graph showed a strong positive correlation between therapist time and effect size (r‐squared= 0.93, correlation coefficient = 0.090 (95%CI 0.056‐0.124) p=0.002).

3.

Publication bias All the studies included in this review were published or in press. There were insufficient studies to construct a meaningful funnel plot.

Discussion

This review found a significant favourable effect on symptoms of hypochondriasis for all forms of psychotherapy that used cognitive behavioural therapy, cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy or behavioural stress management approaches. Although the meta‐analysis of CBT immediately post‐treatment just failed to reach significance, the results at 12‐month follow‐up show a significant difference; therefore we consider this probable evidence for the effectiveness of CBT. Where assessed, there were also significant favourable effects on measures of general functioning (CBT), resource use (psychoeducation), depression (CT, BT, BSM), anxiety (CT, BSM) and physical symptoms (CBT). There was no significant difference in dropout rates between treatment and control groups, which suggests that participants found the treatment acceptable. However, only one study attempted to assess the acceptability of treatments (Clark 1998 a). No studies examined the effectiveness of other forms of psychotherapy (interpersonal therapy, psychodynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, relaxation therapy, counselling) for hypochondriasis.

There were few randomised controlled studies of psychotherapy for hypochondriasis, and the majority used a small sample size. All studies could be considered to be of moderate methodological quality. The outcome measures were inconsistent between studies, with few studies using an unaltered, validated hypochondriasis scale, or stating a primary outcome measure. Most studies used multiple measures for the different dimensions of hypochondriasis and performed separate analyses for each. This approach increases the risk of type one error. This is illustrated by the study of psychoeducation: although the paper reported positive findings, when we made an a priori decision to select a single primary outcome, this review did not find a significant difference between treatment and control. We do not conclude that psychoeducation is ineffective in hypochondriasis, but that more research is needed before it can be recommended as a treatment.

Half of the included studies did not report an intention‐to‐treat analysis and it was not possible to impute missing data. Although this raises the possibility of attrition bias, there was no significant difference in dropout rates between groups for any study. However, when interpreting the generalisability of the results it may be more important to consider the characteristics of people who consent to participate in psychotherapy trials. The treatment of hypochondriasis by psychotherapy techniques depends on the patient's willingness to engage with such treatment. As the conviction that one has a serious physical illness is a core feature of the disorder, it is likely that some patients will be unwilling to participate in psychotherapy, and that these patients would not be represented in trials of psychotherapy. In one trial, only 30% of eligible patients agreed to participate (Barsky 2004). This possibility restricts the generalisability of the findings to hypochondriacal patients who are prepared to undertake psychotherapy. An association has been found between low motivation for psychotherapy and poorer outcome in somatisation disorders (Timmer 2006) and this factor may also be relevant in hypochondriasis. It remains unclear what approaches best help those who do not agree to participate in psychotherapy.

The subgroup analyses identified possible causes of heterogeneity: studies that had the largest amount of therapist time and used visual analogue scales had a larger effect size than studies with smaller amounts of therapist time which used standardised scales. Since both studies that used visual analogue scales were also in the >10hrs total therapist time group, it is not possible to definitely identify one as a causative factor; it seems plausible that a larger amount of face‐to‐face time with a therapist results in a greater improvement in symptoms, although the possibility remains that the use of patient‐rated visual analogue scales detected an artificially large effect size.

These findings suggest that nonspecific factors may play a substantial role in the treatment of hypochondriasis. Waiting list groups do not control for therapist time, which is often an important element in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. It is possible that participants on a waiting list do not expect to recover until they have had psychotherapy, which may increase the size of the effect found in favour of the active treatment. It is of note that the primary outcome of the only study in which the control condition involved regular face‐to‐face reviews did not show a significant difference in the meta‐analysis (Greeven 2004). This suggestion is also consistent with the observation that effect size is positively correlated with amount of therapist time for the included studies. Although a strong correlation was found, this should be interpreted with caution as the number of studies is very small. This review excluded studies which did not compare treatment to a control group such as a waiting list, treatment as usual or some form of placebo, i.e. a condition which would not be expected to produce clinical improvement; this led to the exclusion of some studies which made comparisons between different forms of psychotherapy. Such exclusion criteria may be justified on the grounds that the efficacy of a psychotherapy should be established before comparisons are made to others, but it does not eliminate the conceptual and methodological difficulties of establishing a credible and equivalent placebo condition which adequately controls for nonspecific factors (Borkovec 2005)

The possible importance of non‐specific therapeutic factors is also suggested by the finding of positive outcomes in both arms of studies that had two active treatments. One study devised a non‐specific treatment ‐ behavioural stress management ‐ which deliberately did not address hypochondriasis. Nevertheless this treatment produced significant improvements compared to a waiting list: although they reported sooner and larger initial improvements in the specific treatment arm (CT), there was no significant difference between the two treatments by 12‐month follow‐up (Clark 1998 a). This finding is consistent with trials comparing different treatments for hypochondriasis that did not include a control group, which have reported improvements after treatment with, but no significant difference between, both forms of treatment (Bouman 1998 ‐ CT versus exposure plus response prevention; Buwalda 2006 ‐ group CBT versus group problem‐solving). It is also consistent with a meta‐analysis of recent psychotherapy trials for any condition, which found a significantly smaller effect size when the placebo treatment was structurally similar to the active treatment (Baskin 2003). A review of psychotherapy trials for other somatoform disorders similarly found positive effects for cognitive, behavioural, or cognitive‐behavioural therapies (Allen 2002). However, as in this review, the majority of studies compared the intervention with treatment as usual or a waiting list.

Although statistically significant improvements were shown for psychotherapy in hypochondriasis, it is difficult to interpret their magnitude or clinical significance. No study assessed dichotomous outcomes, e.g. whether participants still met diagnostic criteria for hypochondriasis at the end of treatment. This approach may be justified if one is aiming not to "cure" a disorder but merely to ameliorate the associated symptoms and distress, but it is necessary to be sure that the outcome scales are designed to accurately measure change in core symptoms. The use of validated rating scales would also allow some estimation of the magnitude of change to be made, for example by comparing outcome scores to the case and reference scores of the validation study. Due to the diversity of outcome measures used, it was also not possible to make direct comparisons of effect size between different types of psychotherapy.

It is not possible to draw conclusions about the long‐term effects of psychotherapy on hypochondriasis. The maximum length of follow‐up in the included studies was 12 months, but only one study was designed to make comparisons with a control group at that time point (Barsky 2004). However, as the study authors acknowledge, it is not possible to attribute the effect entirely to the psychotherapy: the GPs of participants in the treatment group were given advice on management, which would have altered the treatment this group received in the 12‐month period following psychotherapy. The efficacy of such advice has been demonstrated in the treatment of somatoform disorders (Rost 1994; Smith 1986; Smith 1995). Although the other studies of CBT reported that significant improvements were maintained at the end of follow‐up (three and seven months), it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about whether this maintenance would occur without treatment in the absence of direct comparisons.

This review has examined several different approaches to the psychotherapeutic treatment of hypochondriasis, but these are not the only ones in clinical practice. The excluded studies evaluated a number of other forms of psychotherapy, including group CBT (Avia 1996; Buwalda 2006; Stern 1991), group psychoeducation (Bouman 2002), group problem‐solving (Buwalda 2006), biofeedback‐assisted relaxation training (Fried 1978), bibliotherapy (Jones 2002) and attention training (Papageorgiou 1998). If these are to be recommended they would need to be tested in randomised controlled trials, but at present there is insufficient evidence to recommend these therapies. Nevertheless, the results of this review are encouraging and provide evidence to support the use of some forms of psychotherapy, namely CT, BSM, BT and CBT, in the treatment of hypochondriasis. Further studies using standardised and validated assessment scales will be needed to confirm these results, assess other forms of psychotherapy and make comparisons between different psychotherapy approaches.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1) Implications for people with hypochondriasis Psychotherapies using cognitive therapy, exposure plus response prevention (i.e. behavioural therapy), cognitive behaviour therapy or behavioural stress management approaches are effective in reducing symptoms of hypochondriasis. However, the findings are based on small numbers of participants and do not allow estimation of the size of the effect, comparison between different types of psychotherapy or whether patients are "cured". Most long‐term outcome data were uncontrolled.

2) Implications for clinicians Hypochondriasis is a condition that is managed largely in primary care. People with hypochondriasis may see a variety of specialists and may be reluctant to see a psychiatrist. Clinicians need to be aware of the existence of this condition and the evidence for effective forms of psychotherapy. They should be aware of what services are available locally and the pathways to access such services. Clinicians need to be able to communicate to patients the nature of the disorder and to encourage them to accept effective treatment. Psychological therapies in primary care are often psychodynamic or person‐centred in approach. These have not been studied in RCTs for hypochondriasis and consideration should be given to referral to specialist services.

3) Implications for managers and policymakers Managers and policymakers need to be aware that there are effective forms of psychotherapy available for the treatment of hypochondriasis and to consider making this treatment available. Studies of these psychotherapies have not addressed the cost‐effectiveness of such treatment or the potential effects on resource use, although it is known that hypochondriasis is associated with significantly more resource use (Creed 2004).

Implications for research.

1) Further well‐designed trials of psychotherapy are required. These should include larger numbers of participants, longer follow‐up times and a credible control condition. Given the prevalence of counselling and psychodynamic therapies in primary care, these should be evaluated for efficacy in hypochondriasis. 2) Further trials should be designed to assess not only whether a psychotherapy is effective, but also which elements are active. 3) To facilitate future comparisons between trials, trials should state a primary outcome measure and use a validated assessment scale for hypochondriasis 4) To facilitate healthcare planning and economic evaluation, trials should include an assessment of effect on healthcare resource use 5) Trials should include an assessment of treatment acceptability and functional improvement in all patients with hypochondriasis 6) There needs to be further investigation of what management strategies are helpful for those with hypochondriasis who are not prepared to engage in psychotherapy.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2007 Review first published: Issue 4, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 July 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank James Rubin, for methodological advice, Michael Dewey, for advice on statistical methods, and Nikola Kern, for translation of a paper from German.

Data and analyses

1.

All forms of psychotherapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/Tablet Placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 5 | 247 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.86 [‐1.25, ‐0.46] |

| 2 Depression | 4 | 230 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.78 [‐1.31, ‐0.24] |

| 3 Anxiety | 3 | 164 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.96 [‐1.64, ‐0.27] |

| 4 Physical Symptoms | 2 | 207 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.41 [‐0.69, ‐0.13] |

| 5 Dropout rates | 5 | 247 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.58, 2.34] |

1.1.

Comparison 1 All forms of psychotherapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/Tablet Placebo, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

1.2.

Comparison 1 All forms of psychotherapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/Tablet Placebo, Outcome 2 Depression.

1.3.

Comparison 1 All forms of psychotherapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/Tablet Placebo, Outcome 3 Anxiety.

1.4.

Comparison 1 All forms of psychotherapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/Tablet Placebo, Outcome 4 Physical Symptoms.

1.5.

Comparison 1 All forms of psychotherapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/Tablet Placebo, Outcome 5 Dropout rates.

2.

Cognitive Therapy vs Waiting List

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 2 | 78 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.26 [‐1.76, ‐0.77] |

| 2 Depression | 2 | 78 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.42 [‐11.28, ‐3.55] |

| 3 Anxiety | 1 | 38 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐14.5 [‐23.41, ‐5.59] |

| 4 Dropout rates | 2 | 79 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.33, 3.52] |

2.1.

Comparison 2 Cognitive Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

2.2.

Comparison 2 Cognitive Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 2 Depression.

2.3.

Comparison 2 Cognitive Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 3 Anxiety.

2.4.

Comparison 2 Cognitive Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 4 Dropout rates.

3.

Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 1 | 42 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐1.11, ‐0.09] |

| 2 Depression | 1 | 42 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐5.10, 5.70] |

| 3 Dropout rates | 1 | 48 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.26, 3.29] |

3.1.

Comparison 3 Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

3.2.

Comparison 3 Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 2 Depression.

3.3.

Comparison 3 Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List, Outcome 3 Dropout rates.

4.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Immediately post treatment | 2 | 104 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.80 [‐1.62, 0.01] |

| 1.2 12 month follow‐up | 1 | 187 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐0.72, ‐0.14] |

| 2 General functioning | 1 | 187 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.19 [5.29, 17.09] |

| 3 Depression | 2 | 107 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.82 [‐1.88, 0.23] |

| 4 Anxiety | 2 | 103 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.79 [‐1.70, 0.12] |

| 5 Physical Symptoms | 1 | 187 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.24 [‐0.40, ‐0.08] |

| 6 Dropout rates | 3 | 294 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.56, 2.32] |

4.1.

Comparison 4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

4.2.

Comparison 4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo, Outcome 2 General functioning.

4.3.

Comparison 4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo, Outcome 3 Depression.

4.4.

Comparison 4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo, Outcome 4 Anxiety.

4.5.

Comparison 4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo, Outcome 5 Physical Symptoms.

4.6.

Comparison 4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy vs Waiting List/Usual Medical Care/ Tablet Placebo, Outcome 6 Dropout rates.

5.

Behavioural Stress Management vs Waiting List

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 1 | 38 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.40 [‐3.87, ‐0.93] |

| 2 Depression | 1 | 38 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐12.7 [‐19.67, ‐5.73] |

| 3 Anxiety | 1 | 37 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐14.9 [‐23.21, ‐6.59] |

| 4 Dropout rates | 1 | 32 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.82 [0.11, 74.51] |

5.1.

Comparison 5 Behavioural Stress Management vs Waiting List, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

5.2.

Comparison 5 Behavioural Stress Management vs Waiting List, Outcome 2 Depression.

5.3.

Comparison 5 Behavioural Stress Management vs Waiting List, Outcome 3 Anxiety.

5.4.

Comparison 5 Behavioural Stress Management vs Waiting List, Outcome 4 Dropout rates.

6.

Psychoeducation vs Waiting List

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.30 [‐4.64, 2.04] |

| 2 Resource use | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.0 [‐11.70, ‐0.30] |

| 3 Physical symptoms | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.20 [‐8.73, 4.33] |

| 4 Dropout rates | 1 | 20 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.25 [0.17, 29.77] |

6.1.

Comparison 6 Psychoeducation vs Waiting List, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

6.2.

Comparison 6 Psychoeducation vs Waiting List, Outcome 2 Resource use.

6.3.

Comparison 6 Psychoeducation vs Waiting List, Outcome 3 Physical symptoms.

6.4.

Comparison 6 Psychoeducation vs Waiting List, Outcome 4 Dropout rates.

7.

Subgroup analysis by diagnostic criteria

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 6 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 DSM‐IIIR | 2 | 93 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.30 [‐1.79, ‐0.81] |

| 1.2 DSM‐IV | 3 | 154 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.61 [‐0.97, ‐0.24] |

| 1.3 Idiosyncratic criteria | 1 | 187 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐0.72, ‐0.14] |

7.1.

Comparison 7 Subgroup analysis by diagnostic criteria, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

8.

Subgroup analysis by total psychotherapy exposure time.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 6 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 <10 hours total therapist time | 3 | 279 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐0.66, ‐0.19] |

| 1.2 >10 hours total therapist time | 3 | 155 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.15 [‐1.52, ‐0.78] |

8.1.

Comparison 8 Subgroup analysis by total psychotherapy exposure time., Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

9.

Subgroup analysis by rating scales used

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 6 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Validated scale/subscale | 4 | 341 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.51 [‐0.73, ‐0.29] |

| 1.2 Visual analogue scale | 2 | 93 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.30 [‐1.79, ‐0.81] |

9.1.

Comparison 9 Subgroup analysis by rating scales used, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

10.

Sensitivity analysis by QRS score

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis | 6 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 QRS <= 25 | 2 | 94 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.06 [‐1.52, ‐0.61] |

| 1.2 QRS > 25 | 4 | 340 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.61 [‐0.99, ‐0.22] |

10.1.

Comparison 10 Sensitivity analysis by QRS score, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis.

11.

All studies regardless of time to outcome

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypochondriasis ‐ all studies | 6 | 434 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.75 [‐1.09, ‐0.41] |

11.1.

Comparison 11 All studies regardless of time to outcome, Outcome 1 Hypochondriasis ‐ all studies.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Participant blinding: no Therapist blinding: no Assessor blinding: yes Analysis: intention‐to‐treat Country: USA Ethics approval: not stated | |

| Participants | Number: active ‐ 102 (76 female; 26 male); control ‐ 85 (67 female; 18 male); total ‐ 187 (143 female; 44 male) Mean (sd) age in years: active ‐ 40.66 (12.60); control ‐ 44.29 (13.75); total ‐ 42.31 Diagnostic criteria: Whitely Index & Somatic Symptom Inventory with cutoff score of 150; 61% of participants had a DSM‐IV diagnosis of hypochondriasis Recruited from: primary care; volunteers Mean (sd) length of illness: active ‐ (); control ‐ (); total ‐ 11 years () Exclusion criteria: 1. <18 years of age; 2. not fluent or literate in English; 3. not having seen GP in last 12 months; 4. major medical morbidity; 5. somatoform pain disorder; 6. psychosis; 7. suicide risk; 8. ongoing disability or compensation claim of litigation. Language restrictions: English only Comorbidity: not stated Number of drop‐outs: active ‐ 10; control ‐ 7; total ‐ 17 | |

| Interventions | Active treatment: cognitive behaviour therapy + letter to GP Control treatment: "usual medical care" Treatment setting: Primary care ‐ letter sent to GPs advising on management, Secondary care outpatient Discipline of therapists: "masters or doctoral degrees and prior CBT experience" Number and duration of sessions: 6 x 90min Interval between sessions: 1 week Total exposure: 9 hours | |

| Outcomes | Length of follow up: 12 months Primary outcome measure: Whitely Index score at 12 months Secondary outcome measures: Health Anxiety Inventory Hypochondriacal Cognitions Questionnaire Somatic Symptom Inventory SCID for DSM‐IV hypochondriasis Somstosensory Amplification Scale Functional Status Questionnaire ‐ intermediate activities of daily living subscale Functional Status Questionnaire ‐ social activities subscale Covariates: Hodgkins Symptom Checklist 90 Duke Severity of Illness Scale 2 ordinal ratings of aggregate medical morbidity by primary care physician | |

| Notes | possible selection bias ‐ only 30% of subjects participated likely performance bias ‐ GPs in active treatment group were given advice on management attrition bias unlikely detection bias unlikely Overall quality assessment: moderate (QRS score = 30) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Participant blinding: not stated Therapist blinding: no Assessor blinding: not stated Analysis: available case Country: England Ethics approval: not stated | |

| Participants | Number: 1st active [CT] ‐ 16; 2nd active [BSM] ‐ 17; control ‐ 15; total ‐ 48 (32 female; 16 male) Median age in years: total ‐ 34; inter‐quartile range 25‐43 Diagnostic criteria: hypochondriasis as assessed by SCID for DSM‐III‐R Recruited from: GPs (70%); medical specialists and psychiatrists (13%); clinical psychologists (13%) Median length of illness: total ‐ 4 years; inter‐quartile range 1‐10 years Exclusion criteria: 1. <30% belief they had a serious illness; 2. health worry not main problem; 3. age <18 or >60; 4. previous treatment with cognitive therapy or behavioural stress management; 5. depressive disorder requiring immediate psychiatric treatment; 6. physical illness which would account for health concerns; 7. psychotic disorder; 8. unwillingness to accept random allocation Language restrictions: English Comorbidity: not stated Number of drop‐outs: 1st active [CT] ‐ 1; 2nd active [BSM] ‐ 1 control ‐ 0; total ‐ 2 | |

| Interventions | Active treatment: 1. Cognitive Therapy; 2. Behavioural Stress Management Control treatment: waiting list Treatment setting: not stated (assumed to be secondary care outpatient) Discipline of therapists: psychologists Number and duration of sessions: 16 x 1 hour with up to 3 booster sessions Interval between sessions: 1 week Total exposure: 16 hours | |

| Outcomes | Length of follow up: 12 months Primary outcome measure: none stated Secondary outcome measures: visual analogue scales: VAS ‐ time seriously worried about health VAS ‐ time free of health worries VAS ‐ avoidance of situations/events that might trigger health worries VAS ‐ checking parts of the body for signs of illness VAS ‐ need for reassurance VAS ‐ health worry related distress‐disability (patient rating) VAS ‐ health worry related distress‐disability (independent rating) Beck Anxiety Inventory Beck Depression Inventory Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale Cognitions questionnaire ‐ frequency of thoughts about standardised set of illnesses Cognitions questionnaire ‐ belief in thoughts about standardised set of illnesses | |

| Notes | unclear selection bias ‐ randomisation not described possible performance bias ‐ participants and therapists not blinded attrition bias unlikely possible detection bias ‐ assessor blinding status not stated Overall quality: moderate (QRS score = 26) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Participant blinding: not stated Therapist blinding: no Assessor blinding: yes Analysis: intention‐to‐treat Country: Italy Ethics approval: not stated | |

| Participants | Number: active ‐ 10 (8 female; 2 male); control ‐ 10 (10 female; 0 male); total ‐ 20 (18 female; 2 male) Mean (sd) age in years: active ‐ 29.5 (7.6); control ‐ 33.9 (7.9); total ‐ 31.7 Diagnostic criteria: DSM‐IV hypochondriasis assessed using SCID‐III‐R Recruited from: secondary care psychosomatic outpatients clinic Mean (sd) length of illness in years: active ‐ 2.28 (1.2); control ‐ 2.9 (2.75); total ‐ 2.59 Exclusion criteria: 1. DSM‐IV 1st/2nd axis comorbidity; 2. active medical illness; 3. severity score <7/9 Language restrictions: Italian Comorbidity: no Number of drop‐outs: active ‐ 2; control ‐ 1; total ‐ 3 | |

| Interventions | Active treatment: Explanatory Therapy Control treatment: waiting list Treatment setting: secondary care outpatients Discipline of therapists: psychiatrists Number and duration of sessions: 8 x 30min Interval between sessions: 2 weeks Total exposure: 4 hours | |

| Outcomes | Length of follow up: 6 months Primary outcome measure: none stated Secondary outcome measures: Clinical Interview for Depression CID change subscale CID hypochondriasis subscale CID nosophobia subscale CID thanatophobia subscale CID bodily preoccupations subscale number of visits to physicians in 3 month period number of laboratory tests in 3 month period Illness Attitude Scale IAS worry about illness subscale IAS concern about pain subscale IAS health habits subscale IAS hypochondriasis subscale IAS thanatophobia subscale IAS nosophobia subscale IAS bodily preoccupations subscale Anxiety Sensitivity Index | |

| Notes | unclear selection bias ‐ randomisation not described possible performance bias ‐ participants not blinded attrition bias unlikely detection bias unlikely Overall quality: moderate (QRS score = 26) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Participant blinding: not stated Therapist blinding: no Assessor blinding: yes Analysis: intention‐to‐treat Country: The Netherlands Ethics approval: yes | |