Abstract

Background

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), sometimes referred to as chronic otitis media (COM), is a chronic inflammation and infection of the middle ear and mastoid cavity, characterised by ear discharge (otorrhoea) through a perforated tympanic membrane. The predominant symptoms of CSOM are ear discharge and hearing loss.

Antibiotics and antiseptics kill or inhibit the micro‐organisms that may be responsible for the infection. Antibiotics can be applied topically or administered systemically via the oral or injection route. Antiseptics are always directly applied to the ear (topically).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of antibiotics versus antiseptics for people with chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM).

Search methods

The Cochrane ENT Information Specialist searched the Cochrane ENT Register; Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4, via the Cochrane Register of Studies); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid Embase; CINAHL; Web of Science; ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the search was 1 April 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with at least a one‐week follow‐up involving patients (adults and children) who had chronic ear discharge of unknown cause or CSOM, where ear discharge had continued for more than two weeks.

The intervention was any single, or combination of, antibiotic agent, whether applied topically (without steroids) or systemically. The comparison was any single, or combination of, topical antiseptic agent, applied as ear drops, powders or irrigations, or as part of an aural toileting procedure.

Two comparisons were topical antiseptics compared to: a) topical antibiotics or b) systemic antibiotics. Within each comparison we separated where both groups of patients had received topical antibiotic a) alone or with aural toilet and b) on top of background treatment (such as systemic antibiotics).

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard Cochrane methodological procedures. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome.

Our primary outcomes were: resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear' (whether otoscopically confirmed or not), measured at between one week and up to two weeks, two weeks to up to four weeks, and after four weeks; health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument; and ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation. Secondary outcomes included hearing, serious complications and ototoxicity measured in several ways.

Main results

We identified seven studies (935 participants) across four comparisons with antibiotics compared against acetic acid, aluminium acetate, boric acid and povidone‐iodine.

None of the included studies reported the outcomes of quality of life or serious complications.

A. Topical antiseptic (acetic acid) versus topical antibiotics (quinolones or aminoglycosides)

It is very uncertain if there is a difference in resolution of ear discharge with acetic acid compared with aminoglycosides at one to two weeks (risk ratio (RR) 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.08; 1 study; 100 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). No study reported results for ear discharge after four weeks. It was very uncertain if there was more ear pain, discomfort or local irritation with acetic acid or topical antibiotics due to the low numbers of participants reporting events (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.34; 2 RCTs; 189 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). No differences between groups were reported narratively for hearing (quinolones) or suspected ototoxicity (aminoglycosides) (very low‐certainty evidence).

B. Topical antiseptic (aluminium acetate) versus topical antibiotics

No results for the one study comparing topical antibiotics with aluminium acetate could be used in the review.

C. Topical antiseptic (boric acid) versus topical antibiotics (quinolones)

One study reported more participants with resolution of ear discharge when using topical antibiotics (quinolones) compared with boric acid ear drops at between one to two weeks (risk ratio (RR) 1.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.48 to 2.35; 1 study; 411 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). This means that one additional person will have resolution of ear discharge for every four people receiving topical antibiotics (compared with boric acid) at two weeks. No study reported results for ear discharge after four weeks. There was a bigger improvement in hearing in the topical antibiotic group compared to the topical antiseptic group (mean difference (MD) 2.79 decibels (dB), 95% CI 0.48 to 5.10; 1 study; 390 participants; low‐certainty evidence) but this difference may not be clinically significant.

There may be more ear pain, discomfort or irritation with boric acid compared with quinolones (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.98; 2 studies; 510 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Suspected ototoxicity was not reported.

D. Topical antiseptic (povidone‐iodine) versus topical antibiotics (quinolones)

It is uncertain if there is a difference between quinolones and povidone‐iodine with respect to resolution of ear discharge at one to two weeks (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.26; 1 RCT, 39 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The study reported qualitatively that there were no differences between the groups for hearing and no patients developed ototoxic effects (very low‐certainty evidence). No results for resolution of ear discharge beyond four weeks, or ear pain, discomfort or irritation, were reported.

E. Topical antiseptic (acetic acid) + aural toileting versus topical + systemic antibiotics (quinolones)

One study reported that participants receiving topical and oral antibiotics had less resolution of ear discharge compared with acetic acid ear drops and aural toileting (suction clearance every two days) at one month (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.90; 100 participants). The study did not report results for resolution of ear discharge at between one to two weeks, ear pain, discomfort or irritation, hearing or suspected ototoxicity.

Authors' conclusions

Treatment of CSOM with topical antibiotics (quinolones) probably results in an increase in resolution of ear discharge compared with boric acid at up to two weeks. There was limited evidence for the efficacy of other topical antibiotics or topical antiseptics and so we are unable to draw conclusions. Adverse events were not well reported.

Plain language summary

Topical antiseptics compared with antibiotics for people with chronic suppurative otitis media

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review is to find out whether topical antiseptics are more effective than antibiotics in treating chronic suppurative otitis media. The review authors collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question.

Key messages

There is not much evidence comparing topical antiseptics with topical antibiotics. The evidence is very uncertain as to whether antibiotics or topical antiseptics are more effective for reducing ear discharge, except that topical antibiotics are likely to be more effective than boric acid.

What was studied in the review?

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is a long‐term (chronic) swelling and infection of the middle ear, with ear discharge (otorrhoea) through a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum). The main symptoms of CSOM are ear discharge and hearing loss.

Antibiotics are the most commonly used treatment for CSOM. Antibiotics can either be 'topical' (put into the ear canal as ear drops, ointments, sprays or creams) or 'systemic' (taken either by mouth or by an injection into a muscle or vein). Topical antiseptics (antiseptics put directly into the ear as ear drops or as a powder) are a possible treatment for CSOM. Both antibiotics and topical antiseptics kill or stop the growth of the micro‐organisms that may be responsible for the infection.

Antibiotics and topical antiseptics can be used on their own or added to other treatments for CSOM, such as antibiotics or ear cleaning (aural toileting). It was important in this review to examine whether there were any adverse effects from using antibiotics and antiseptics. Possible adverse events could include irritation of the skin within the outer ear, which may cause discomfort, pain or itching. Some antibiotics and antiseptics (such as alcohol) can also be toxic to the inner ear (ototoxicity), which means that they may cause irreparable hearing loss (sensorineural), dizziness or ringing in the ear (tinnitus).

What are the main results of the review?

We found seven studies, which included 935 participants. We found evidence for four different types of topical antiseptics: acetic acid, aluminium acetate, boric acid and povidone‐iodine.

Comparison of antibiotics to acetic acid, aluminium acetate or povidone‐iodine

Compared to acetic acid, aluminium acetate and povidone‐iodine it is very uncertain whether topical antibiotics or systemic antibiotics improve the resolution of ear discharge in patients with CSOM because the certainty of the evidence is very low. It is not possible to know whether there is a difference between the groups for any other outcome.

Comparison of antibiotics to boric acid

We included two studies (532 participants), which showed evidence that topical antibiotics (quinolones) are likely to be better than boric acid at resolving ear discharge at one to two weeks. There also may be less ear discomfort (pain, irritation and bleeding) and a bigger improvement in hearing with topical antibiotics compared with boric acid.

How up to date is this review?

The evidence is up to date to April 2019.

Summary of findings

Background

This is one of a suite of Cochrane Reviews evaluating the comparative effectiveness of non‐surgical interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) using topical antibiotics, topical antibiotics with corticosteroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antiseptics and aural toileting (ear cleaning) methods (Table 4).

1. Table of Cochrane Reviews.

| Topical antibiotics with steroids | Topical antibiotics | Systemic antibiotics | Topical antiseptics | Aural toileting (ear cleaning) | |

| Topical antibiotics with steroids | Review CSOM‐4 | ||||

| Topical antibiotics | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐1 | |||

| Systemic antibiotics | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐3 | Review CSOM‐2 | ||

| Topical antiseptics | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐6 | Review CSOM‐6 | Review CSOM‐5 | |

| Aural toileting | Review CSOM‐4 | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Review CSOM‐7 |

| Placebo (or no intervention) | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐1 | Review CSOM‐2 | Review CSOM‐5 | Review CSOM‐7 |

CSOM‐1: Topical antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Brennan‐Jones 2018a).

CSOM‐2: Systemic antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Chong 2018a).

CSOM‐3: Topical versus systemic antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Chong 2018b).

CSOM‐4: Topical antibiotics with steroids for chronic suppurative otitis media (Brennan‐Jones 2018b).

CSOM‐5: Topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Head 2018a).

CSOM‐6: Antibiotics versus topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Head 2018b).

CSOM‐7: Aural toilet (ear cleaning) for chronic suppurative otitis media (Bhutta 2018).

This review compares the effectiveness of topical antibiotics (without steroids), or systemic antibiotics, against topical antiseptics for CSOM.

Description of the condition

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), which is also often referred to as chronic otitis media (COM), is a chronic inflammation and infection of the middle ear and mastoid cavity, characterised by ear discharge (otorrhoea) through a perforated tympanic membrane.

The predominant symptoms of CSOM are ear discharge and hearing loss. Ear discharge can be persistent or intermittent, and many sufferers find it socially embarrassing (Orji 2013). Some patients also experience discomfort or earache. Most patients with CSOM experience temporary or permanent hearing loss with average hearing levels typically between 10 and 40 decibels (Jensen 2013). The hearing loss can be disabling, and it can have an impact on speech and language skills, employment prospects, and on children’s psychosocial and cognitive development, including academic performance (Elemraid 2010; Olatoke 2008; WHO 2004). Consequently, quality of life can be affected. CSOM can also progress to serious complications in rare cases (and more often when cholesteatoma is present): both extracranial complications (such as mastoid abscess, postauricular fistula and facial palsy) and intracranial complications (such as otitic meningitis, lateral sinus thrombosis and cerebellar abscess) have been reported (Dubey 2007; Yorgancılar 2013).

CSOM is estimated to have a global incidence of 31 million episodes per year, or 4.8 new episodes per 1000 people (all ages), with 22% of cases affecting children under five years of age (Monasta 2012; Schilder 2016). The prevalence of CSOM varies widely between countries, but it disproportionately affects people at socio‐economic disadvantage. It is rare in high‐income countries, but common in many low‐ and middle‐income countries (Mahadevan 2012; Monasta 2012; Schilder 2016; WHO 2004).

Definition of disease

There is no universally accepted definition of CSOM. Some define CSOM in patients with a duration of otorrhoea of more than two weeks but others may consider this an insufficient duration, preferring a minimum duration of six weeks or more than three months (Verhoeff 2006). Some include diseases of the tympanic membrane within the definition of CSOM, such as tympanic perforation without a history of recent ear discharge, or the disease cholesteatoma (a growth of the squamous epithelium of the tympanic membrane).

In accordance with a consensus statement, here we use CSOM only to refer to tympanic membrane perforation, with intermittent or continuous ear discharge (Gates 2002). We have used a duration of otorrhoea of two weeks as an inclusion criterion, in accordance with the definition used by the World Health Organization, but we have used subgroup analyses to explore whether this is a factor that affects observed treatment effectiveness (WHO 2004).

Many people affected by CSOM do not have good access to modern primary healthcare, let alone specialised ear and hearing care, and in such settings health workers may be unable to view the tympanic membrane to definitively diagnose CSOM. It can also be difficult to view the tympanic membrane when the ear discharge is profuse. Therefore we have also included, as a subset for analysis, studies where participants have had chronic ear discharge for at least two weeks, but where the diagnosis is unknown.

At‐risk populations

Some populations are considered to be at high risk of CSOM. There is a high prevalence of disease among Indigenous people such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian, Native American and Inuit populations. This is likely due to an interplay of factors, including socio‐economic deprivation and possibly differences resulting from population genetics (Bhutta 2016). Those with primary or secondary immunodeficiency are also susceptible to CSOM. Children with craniofacial malformation (including cleft palate) or chromosomal mutations such as Down syndrome are prone to chronic non‐suppurative otitis media ('glue ear'), and by extrapolation may also be at greater risk of suppurative otitis media. The reasons for this association with craniofacial malformation are not well understood, but may include altered function of the Eustachian tube, coexistent immunodeficiency, or both. These populations may be less responsive to treatment and more likely to develop CSOM, recurrence or complications.

Children who have a grommet (ventilation tube) in the tympanic membrane to treat glue ear or recurrent acute otitis media may be more prone to develop CSOM; however, their pathway to CSOM may differ and therefore they may respond differently to treatment. Children with grommets who have chronic ear discharge meeting the CSOM criteria are therefore considered to be a separate high‐risk subgroup (van der Veen 2006).

Treatment

Treatments for CSOM may include topical antibiotics (administered into the ear) with or without steroids, systemic antibiotics (given either by mouth or by injection), topical antiseptics and ear cleaning (aural toileting), all of which can be used on their own or in various combinations. Whereas primary healthcare workers or patients themselves can deliver some treatments (for example, some aural toileting and antiseptic washouts), in most countries antibiotic therapy requires prescription by a doctor. Surgical interventions are an option in cases where complications arise or in patients who have not responded to pharmacological treatment; however, there is a range of practice in terms of the type of surgical intervention that should be considered and the timing of the intervention. In addition, access to or availability of surgical interventions is setting‐dependent. This series of Cochrane Reviews therefore focuses on non‐surgical interventions. In addition, most clinicians consider cholesteatoma to be a variant of CSOM, but acknowledge that it will not respond to non‐surgical treatment (or will only respond temporarily) (Bhutta 2011). Therefore, studies in which more than half of the participants were identified as having cholesteatoma are not included in these reviews.

Description of the intervention

Antibiotics are the most commonly used treatment for CSOM. They can be administered topically (as drops, ointments, sprays or creams to the affected area) or systemically (either by mouth or by injection into a vein (intravenous) or muscles (intramuscular)).

Topical application of antibiotics has the advantage of potentially delivering high concentrations of antibiotic to the affected area, whereas systemic antibiotics are absorbed and distributed throughout the body. However, the penetration of topical antibiotics into the middle ear may be compromised if the perforation in the tympanic membrane is small or there is copious mucopurulent discharge in the ear canal that cannot be cleaned. It may also be difficult to achieve compliance with topical dosing in young children. In these cases, systemic antibiotics may have an advantage.

Antiseptics are substances that kill or inhibit the growth and development of micro‐organisms. Agents that have been used for treating CSOM include povidone‐iodine, aluminium acetate, boric acid, chlorhexidine, alcohol, acetic acid and hydrogen peroxide. Antiseptics can be delivered as drops or as washes using a syringe. The frequency of administration and duration of treatment can vary. Syringing may bring additional benefit by flushing out debris or pus, thus reducing the overall bacterial load. Antiseptics can be used alone or in addition to other treatments for CSOM, such as antibiotics or aural toileting.

How the intervention might work

CSOM is a chronic and often polymicrobial (involving more than one micro‐organism) infection of the middle ear. Broad‐spectrum antibiotics such as second‐generation quinolones and aminoglycosides, which are often active against the most frequently cultured micro‐organisms (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus), are therefore commonly used (Mittal 2015) (Table 5). It is possible that antibiotics for CSOM that target Pseudomonas aeruginosa may have an advantage over antibiotics that do not. Dose and duration of treatment are also important factors but are less likely to affect relative effectiveness if given within the therapeutic range. Generally, treatment for at least five days is necessary and a duration of one to two weeks is sufficient to resolve uncomplicated infections. However, in some cases it may take more than two weeks for the ear to become dry and therefore longer follow‐up (more than four weeks) may be needed to monitor for recurrence of discharge.

2. Examples of antibiotics classes and agents with anti‐Pseudomonas activity.

| Class of antibiotics | Examples | Route of administration |

| Quinolones | Ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin | Oral, intravenous, topical |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin, tobramycin | Topical or parenteral |

| Neomycin/framycetin | Only topical | |

| Cephalosporins | Ceftazidime | Parenteral |

| Penicillins | Ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid | Parenteral |

| Monobactams | Aztreonam | Parenteral |

Topical antiseptics are administered to the ear to inhibit the micro‐organisms that may be responsible for the condition. Although the mechanism of action of most antiseptics is thought to relate to disruption of the bacterial cell wall followed by penetration into the cell and action at the target site(s), different groups of antiseptics have different properties (e.g. iodines, alcohols, acids) (Table 6). We therefore analysed these groups separately and pooling only occurred where there was no evidence of a difference in effect.

3. Antiseptics that have been used to treat CSOM.

| Antiseptic agent used aurally | Target and mechanism of action |

| Rubbing alcohol (ethanol, isopropanol) | Penetrating agents that cause loss of cellular membrane function, leading to release of intracellular components, denaturing of proteins, and inhibition of DNA, RNA, protein and peptidoglycan synthesis. |

| Povidone‐iodine | Highly active oxidising agents that destroy cellular activity of proteins. Disrupts oxidative phosphorylation and membrane‐associated activities. Iodine reacts with cysteine and methionine thiol groups, nucleotides and fatty acids, resulting in cell death. |

| Chlorhexidine | Membrane‐active agents that damage cell wall and outer membrane, resulting in collapse of membrane potential and intracellular leakage. Enhanced passive diffusion mediates further uptake, causing coagulation of cytosol. |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Produces hydroxyl free radicals that function as oxidants, which react with lipids, proteins and DNA. Sulfhydryl groups and double bonds are targeted in particular, thus increasing cell permeability. |

| Boric acid | It is likely that the change in the pH media of the ear canal interrupts the growth of bacteria by affecting the amino acid, which causes alteration in the three‐dimensional structure of bacterial enzymes. Extreme changes in pH cause protein denaturation. |

| Aluminium acetate/acetic acid | Acetic acid changes the pH media of the ear canal and interrupts the growth of bacteria by affecting the amino acid, which causes alteration in the three‐dimensional structure of bacterial enzymes. Extreme changes in pH cause protein denaturation. Aluminium acetate is an astringent that helps reduce itching, stinging and inflammation. |

Sources: Gupta 2015; McDonnell 1999; Sheldon 2005.

Some antibiotics (such as aminoglycosides) and antiseptics (such as chlorhexidine or alcohol) can be toxic to the inner ear (ototoxicity), which might be experienced as sensorineural hearing loss, dizziness or tinnitus. For antibiotics, ototoxicity is less likely to be a risk when applied topically in patients with CSOM (Phillips 2007).

For both topical antibiotics and antiseptics, local discomfort, ear pain or itching may occur through the action of putting ear drops into the ear or because the topical antibiotics/antiseptics or their excipients cause chemical or allergic irritation of the skin of the outer ear.

Systemic antibiotics can have off‐target side effects, for example diarrhoea or nausea. However, the risk or incidence of these events is not expected to be different from other common infections since the doses and duration of treatment used are similar in CSOM. A broader concern is the association of the overuse of antibiotics with increasing resistance among community‐ and hospital‐acquired pathogens.

Why it is important to do this review

Although antibiotics are widely recommended as first‐line treatment for CSOM, topical antiseptic agents generally cost less. They are also more readily available, do not require prescription by a doctor and do not need refrigerated transport. These factors make them an attractive option in resource‐constrained environments. Evidence‐based knowledge of the relative effectiveness of antibiotics and topical antiseptics could help to optimise their use.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of antibiotics versus antiseptics for people with chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies with the following design characteristics:

Randomised controlled trials (including cluster‐randomised trials where the unit of randomisation is the setting or operator) and quasi‐randomised trials.

Patients were followed up for at least one week.

We excluded studies with the following design characteristics:

Cross‐over trials, because CSOM is not expected to be a stable chronic condition. Unless data from the first phase were available, we excluded such studies.

Studies that randomised participants by ear (within‐patient controlled) because, by definition, the effects of systemic treatments are not localised. This applies to studies that compared systemic antibiotics versus topical antiseptics. Note: we did not exclude studies comparing topical antibiotics with topical antiseptics that randomised participants by ear but we analysed these using the methods outlined in Unit of analysis issues.

Types of participants

We included studies with patients (adults and children) who had:

chronic ear discharge of unknown cause; or

chronic suppurative otitis media.

We defined patients with chronic ear discharge as patients with at least two weeks of ear discharge, where the cause of the discharge was unknown.

We defined patients with chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) as patients with:

chronic or persistent ear discharge for at least two weeks; and

a perforated tympanic membrane.

We did not exclude any populations based on age, risk factors (cleft palate, Down syndrome), ethnicity (e.g. Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders) or the presence of ventilation tubes (grommets). Where available, we recorded these factors in the patient characteristics section during data extraction from the studies. If any of the included studies recruited these patients as a majority (80% or more), we analysed them in a subgroup analysis (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

We excluded studies where the majority (more than 50%) of participants:

had an alternative diagnosis to CSOM (e.g. otitis externa);

had underlying cholesteatoma;

had ear surgery within the last six weeks.

We did not include studies designed to evaluate interventions in the immediate peri‐surgical period, which were focused on assessing the impact of the intervention on the surgical procedure or outcomes.

Types of interventions

Antibiotics

We included all topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical antibiotics were applied directly into the ear canal. The most common formulations are ear drops but other formulations such as sprays have also been included.

Systemic antibiotics are administered orally or parenterally (intramuscular or intravenous).

We excluded studies that conducted swabs and tests for antimicrobial sensitivity and then based the choice of antibiotics for each participant on the results of the laboratory test.

Duration

At least five days of treatment with antibiotics was required, except for antibiotics where a shorter duration has been suggested as equivalent (e.g. azithromycin for systemic antibiotics).

Dose

There was no limitation on the dose or frequency of administration.

Topical antiseptics

Any single, or combination of, topical antiseptic agent of any class including (but not limited to) povidone‐iodine, aluminium acetate, boric acid, chlorhexidine, alcohol and hydrogen peroxide. The topical antiseptics could be applied directly into the ear canal as ear drops, powders or irrigations, or as part of an aural toileting procedure.

Dose/duration

There was no limitation on the dose, duration or frequency of application.

Comparisons

We analysed topical antibiotics and systemic antibiotics as separate comparisons:

Topical antibiotics versus topical antiseptics.

Systemic antibiotics versus topical antiseptics.

We analysed these as three main scenarios depending on which common therapy was applied in the background:

Topical or systemic antibiotics versus topical antiseptics as a single treatment (main therapy): this included studies where all participants in both treatment groups either received no other treatment or only received aural toileting. This also included situations where antiseptics were applied only once (e.g. as part of microsuction at the start of treatment).

Topical or systemic antibiotics versus topical antiseptics as an add‐on therapy to antiseptics: this included studies where all participants in both treatment groups also used a daily antiseptic, which was a different type to the antiseptic under investigation, with or without aural toileting.

Topical or systemic antibiotics versus topical antiseptics as an add‐on therapy to other systemic or topical antibiotics: this included studies where all participants in both treatment groups also received a systemic or topical antibiotic, which was a different type to the antibiotic under investigation, with or without aural toileting or antiseptics.

Many comparison pairs were possible in this review. The main comparisons of interest that we have summarised and presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables are:

topical antibiotics versus topical antiseptics as single therapies (main treatments); and

systemic antibiotics versus topical antiseptics as single therapies (main treatments).

Types of outcome measures

We analysed the following outcomes in the review, but we did not use them as a basis for including or excluding studies.

We extracted and reported data from the longest available follow‐up for all outcomes.

Primary outcomes

-

Resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear' (whether otoscopically confirmed or not), measured at:

between one week and up to two weeks;

two weeks to up to four weeks; and

after four weeks.

Health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument for CSOM (e.g. Chronic Otitis Media Questionnaire (COMQ)‐12 (Phillips 2014a; Phillips 2014b; van Dinther 2015), Chronic Otitis Media Outcome Test (COMOT)‐15 (Baumann 2011), Chronic Ear Survey (CES) (Nadol 2000)).

Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation.

Secondary outcomes

Hearing, measured as the pure‐tone average of air conduction thresholds across four frequencies tested (500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz) of the affected ear. If this was not available, we reported the pure‐tone average of the thresholds measured.

Serious complications, including intracranial complications (such as otitic meningitis, lateral sinus thrombosis and cerebellar abscess) and extracranial complications (such as mastoid abscess, postauricular fistula and facial palsy), and death.

-

Ototoxicity; this was measured as 'suspected ototoxicity' as reported by the studies where available, and as the number of people with the following symptoms that may be suggestive of ototoxicity:

sensorineural hearing loss;

balance problems/dizziness/vertigo;

tinnitus.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane ENT Information Specialist conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. The date of the search was 1 April 2019.

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist searched:

the Cochrane ENT Register (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies to 1 April 2019);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4) (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies Web to 1 April 2019);

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946 to 1 April 2019);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 1 April 2019);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 1 April 2019);

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database), lilacs.bvsalud.org (search to 1 April 2019);

Web of Knowledge, Web of Science (1945 to 1 April 2019);

ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov (search via the Cochrane Register of Studies to 1 April 2019);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (search to 1 April 2019).

We also searched:

IndMed (search to 22 March 2018);

African Index Medicus (search to 22 March 2018).

The search strategies for major databases are detailed in Appendix 1. The Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. The strategies were designed to identify all relevant studies for a suite of reviews on various interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media (Bhutta 2018; Brennan‐Jones 2018a; Brennan‐Jones 2018b; Chong 2018a; Chong 2018b; Head 2018a; Head 2018b). Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2011).

Searching other resources

We scanned the reference lists of identified publications for additional trials and contacted trial authors where necessary. In addition, the Information Specialist searched Ovid MEDLINE to retrieve existing systematic reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. The Information Specialist also ran non‐systematic searches of Google Scholar to retrieve grey literature and other sources of potential trials.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects. We considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

We contacted original authors for clarification and further data if trial reports were unclear and we arranged translations of papers where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two review authors (KH/LYC) independently screened all titles and abstracts of the references obtained from the database searches to identify potentially relevant studies. At least two review authors (KH/LYC) evaluated the full text of each potentially relevant study to determine whether it met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review.

We resolved any differences by discussion and consensus, with the involvement of a third author for clinical and methodological input where necessary.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors (KH/LYC/CBJ/MB) independently extracted data from each study using a standardised data collection form (see Appendix 2). Whenever a study had more than one publication, we retrieved all publications to ensure complete extraction of data. Where there were discrepancies in the data extracted by different review authors, we checked these against the original reports and resolved any differences by discussion and consensus, with the involvement of a third author or a methodologist where appropriate. We contacted the original study authors for clarification or for missing data whenever possible. If differences were found between publications of a study, we contacted the original authors for clarification. We used data from the main paper(s) if no further information was found.

We included key characteristics of the included studies, such as study design, setting (including location), year of study, sample size, age and sex of participants, and how outcomes were defined or collected in the studies. In addition, we also collected baseline information on prognostic factors or effect modifiers (see Appendix 2). For this review, this included the following information whenever available:

duration of ear discharge at entry to the study;

diagnosis of ear discharge (where known);

number people who may have been at higher risk of CSOM, including those with cleft palate or Down syndrome;

ethnicity of participants including the number who were from Indigenous populations;

number who had previously had ventilation tubes (grommets) inserted (and, where known, the number who had tubes still in place);

number who had previous ear surgery;

number who had previous treatments for CSOM (non‐responders, recurrent versus new cases).

We recorded concurrent treatments alongside the details of the interventions used. See the 'Data extraction form' in Appendix 2 for more details.

For the outcomes of interest to the review, we extracted the findings of the studies on an available case analysis basis, i.e. we included data from all patients available at the time points based on the treatment randomised whenever possible, irrespective of compliance or whether patients had received the treatment as planned.

In addition to extracting pre‐specified information about study characteristics and aspects of methodology relevant to risk of bias, we extracted the following summary statistics for each trial and each outcome:

For continuous data: the mean values, standard deviations and number of patients for each treatment group. Where endpoint data were not available, we extracted the values for change from baseline. We analysed data from disease‐specific quality of life scales such as COMQ‐12, COMOT‐15 and CES as continuous data.

For binary data: the number of participants who experienced an event and the number of patients assessed at the time point.

For ordinal scale data: if the data appeared to be approximately normally distributed or if the analysis that the investigators performed suggested parametric tests were appropriate, then we treated the outcome measures as continuous data. Alternatively, if data were available, we converted it into binary data.

Time‐to‐event outcomes: we were not expecting any outcomes to be measured as time‐to‐event data. However, if outcomes such as resolution of ear discharge were measured in this way, we would have reported the hazard ratios.

For resolution of ear discharge, we extracted the longest available data within the time frame of interest, defined as from one week up to (and including) two weeks (7 days to 14 days), from two weeks up to (and including) four weeks (15 to 28 days), and after four weeks (28 days or one month).

For other outcomes, we reported the results from the longest available follow‐up period.

Extracting data for pain/discomfort and adverse effects

For these outcomes, there were variations in how studies had reported the outcomes. For example, some studies reported both 'pain' and 'discomfort' separately whereas others did not. Prior to the commencement of data extraction, we agreed and specified a data extraction algorithm for how data should be extracted.

We extracted data for serious complications as a composite outcome. If a study reported more than one complication and we could not distinguish whether these occurred in one or more patients, we extracted the data with the highest incidence to prevent double counting.

Extracting data from figures

Where values for primary or secondary outcomes were shown as figures within the paper, we attempted to contact the study authors to try to obtain the raw values. When the raw values were not provided, we extracted information from the graphs using an online data extraction tool, using the best quality version of the relevant figures available.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors (KH/LYC/CBJ/MB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study. We followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011), using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. With this tool we assessed the risk of bias as 'low', 'high' or 'unclear' for each of the following six domains:

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting;

other sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We summarised the effects of dichotomous outcomes (e.g. proportion of patients with complete resolution of ear discharge) as risk ratios (RR) with confidence intervals (CIs). For the key outcomes that are presented in the 'Summary of findings' table, we expressed the results as absolute numbers based on the pooled results and compared to the assumed risk. We also calculated the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) using the pooled results. The assumed baseline risk was typically either (a) the median of the risks of the control groups in the included studies, this being used to represent a 'medium‐risk population' or, alternatively, (b) the average risk of the control groups in the included studies, which is used as the 'study population' (Handbook 2011). If a large number of studies were available, and where appropriate, we would have also attempted to present additional data based on the assumed baseline risk in (c) a low‐risk population and (d) a high‐risk population.

For continuous outcomes, we expressed treatment effects as a mean difference (MD) with standard deviation (SD). If different scales were used to measure the same outcome, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) and provided a clinical interpretation of the SMD values.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over studies

This review did not use data from phase II of cross‐over studies.

The ear as the unit of randomisation: within‐patient randomisation in patients with bilateral ear disease

For data from studies where 'within‐patient' randomisation was used (i.e. studies where both ears (right versus left) were randomised) we adjusted the analyses for the paired nature of the data (Elbourne 2002; Stedman 2011), as outlined in section 16.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011).

The ear as the unit of randomisation: non‐paired randomisation in patients with bilateral ear disease

Some patients with bilateral disease may have received the same treatment in both ears, whereas others received a different treatment in each ear. We did not exclude these studies, but we only reported the data if specific pairwise adjustments were completed or if sufficient data were obtained to be able to make the adjustments.

The patient as the unit of randomisation

Some studies randomised by patient and those with bilateral CSOM received the same intervention for both ears. In some studies the results may be reported as a separate outcome for each ear (the total number of ears is used as the denominator in the analysis). The correlation of response between the left ear and right ear when given the same treatment was expected to be very high, and if both ears were counted in the analysis this was effectively a form of double counting, which may be especially problematic in smaller studies if the number of people with bilateral CSOM was unequal. We did not exclude these studies, but we only reported the results if the paper presented the data in such a way that we could include the data from each participant only once (one data point per participant) or if we had enough information to reliably estimate the effective sample size or inflated standard errors as presented in chapter 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011). If this was not possible, we attempted to contact the authors for more information. If there was no response from the authors, then we did not include data from these studies in the analysis.

If we found cluster‐randomised trials by setting or operator, we analysed these according to the methods in section 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the study authors via email whenever the outcome of interest was not reported but the methods of the study had suggested that the outcome had been measured. We did the same if not all of the data required for the meta‐analysis were reported, unless the missing data were standard deviations. If standard deviation data were not available, we approximated these using the standard estimation methods from P values, standard errors or 95% CIs if these were reported, as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011). Where it was impossible to estimate these, we contacted the study authors.

Apart from imputations for missing standard deviations, we did not conduct any other imputations. We extracted and analysed data for all outcomes using the available case analysis method.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity (which may be present even in the absence of statistical heterogeneity) by examining the included studies for potential differences in the types of participants recruited, interventions or controls used, and the outcomes measured. We did not pool studies where the clinical heterogeneity made it unreasonable to do so.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plots and by considering the Chi² test (with a significance level set at P value < 0.10) and the I² statistic, which calculated the percentage of variability that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, with I² values over 50% suggesting substantial heterogeneity (Handbook 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias as within‐study outcome reporting bias and between‐study publication bias.

Outcome reporting bias (within‐study reporting bias)

We assessed within‐study reporting bias by comparing the outcomes reported in the published report against the study protocol, whenever this could be obtained. If the protocol was not available, we compared the outcomes reported to those listed in the methods section. If results were mentioned but not reported adequately in a way that allowed analysis (e.g. the report only mentioned whether the results were statistically significant or not), bias in a meta‐analysis was likely to occur. We tried to find further information from the study authors, but if no further information could be obtained, we noted this as being a high risk of bias. Where there was insufficient information to judge the risk of bias, we noted this as an unclear risk of bias (Handbook 2011).

Publication bias (between‐study reporting bias)

We intended to create funnel plots if sufficient studies (more than 10) were available for an outcome. If we had observed asymmetry of the funnel plot, we would have conducted a more formal investigation using the methods proposed by Egger 1997.

Data synthesis

We conducted all meta‐analyses using Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014). For dichotomous data, we analysed treatment differences as a risk ratio (RR) calculated using the Mantel‐Haenszel methods. We analysed time‐to‐event data using the generic inverse variance method.

For continuous outcomes, if all the data were from the same scale, we pooled mean values obtained at follow‐up with change outcomes and reported this as a MD. However, if the SMD had to be used as an effect measurement, we did not pool change and endpoint data.

When statistical heterogeneity is low, random‐effects versus fixed‐effect methods yield trivial differences in treatment effects. However, when statistical heterogeneity is high, the random‐effects method provides a more conservative estimate of the difference.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We subgrouped studies where most participants (80% or more) met the criteria stated below in order to determine whether the effect of the intervention was different compared to other patients. Due to the risks of reporting and publication bias with unplanned subgroup analyses of trials, we only analysed subgroups reported in studies if these were prespecified and stratified at randomisation.

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses regardless of whether statistical heterogeneity was observed for studies that included patients identified as high‐risk (i.e. thought to be less responsive to treatment and more likely to develop CSOM, recurrence or complications) and patients with ventilation tubes (grommets). 'High‐risk' patients include Indigenous populations (e.g. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Native Americans and Inuit populations of Alaska, Canada and Greenland), people with craniofacial malformation (e.g. cleft palate), Down syndrome and people with known immunodeficiency.

We planned to present the main analyses of this review in the form of forest plots based on this main subgroup analysis.

For the high‐risk group, this applied to the outcomes resolution of ear discharge (dry ear), quality of life, pain/discomfort, development of complications and hearing loss.

For patients with ventilation tubes, this applied to the outcome resolution of ear discharge (dry ear) for the time point of four weeks or more because this group was perceived to be at lower risk of treatment failure and recurrence than other patient groups. If statistical heterogeneity was observed, we also conducted subgroup analysis for the effect modifiers below. If there were statistically significant subgroup effects, we presented these subgroup analysis results as forest plots.

For this review, effect modifiers included:

Diagnosis of CSOM: it was likely that some studies would include patients with chronic ear discharge but who had not had a diagnosis of CSOM. Therefore, we subgrouped studies where most patients (80% or more) met the criteria for CSOM diagnosis in order to determine whether the effect of the intervention was different compared to patients where the precise diagnosis was unknown and inclusion into the study was based purely on chronic ear discharge symptoms.

Duration of ear discharge: there is uncertainty about whether the duration of ear discharge prior to treatment has an impact on the effectiveness of treatment and whether more established disease (i.e. discharge for more than six weeks) is more refractory to treatment compared with discharge of a shorter duration (i.e. less than six weeks).

Patient age: patients who were younger than two years old versus patients up to six years old versus adults. Patients under two years are widely considered to be more difficult to treat.

We presented the results as subgroups regardless of the presence of statistical heterogeneity based on these three factors:

Class of antibiotics. We grouped by pharmacological class, e.g. quinolones, aminoglycosides, penicillins etc. The rationale for this was that different classes may have had different effectiveness and side effect profiles.

Spectrum of activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (groups with known activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa versus groups without activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This is the most commonly found bacteria in patients with CSOM and its presence is associated with tissue damage.

Type of antiseptic used in the comparison arm (e.g. iodines, alcohols, acids). This is because different types of antiseptic have different mechanisms of action and therefore the treatment effects and adverse effect profiles are likely to be different.

When other antibiotics were also used as a common treatment in both the intervention and comparison group, we investigated the class and antipseudomonal activity when statistical heterogeneity was present and could not be explained by the other subgroup analyses.

No other subgroups based on the pharmacological properties of antibiotics were planned, but we considered the method and frequency of aural toileting if there was remaining unexplained heterogeneity despite conducting the other subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to determine whether the findings were robust to the decisions made in the course of identifying, screening and analysing the trials. We planned to conduct sensitivity analysis for the following factors, whenever possible:

Impact of model chosen: fixed‐effect versus random‐effects model.

Risk of bias of included studies: excluding studies with high risk of bias (we defined these as studies that have a high risk of allocation concealment bias and a high risk of attrition bias (overall loss to follow‐up of 20%, differential follow‐up observed)).

Where there was statistical heterogeneity, studies that only recruited patients who had previously not responded to one of the treatments under investigation in the RCT. Studies that specifically recruited patients who did not respond to a treatment could potentially have reduced the relative effectiveness of an agent.

If any of these investigations found a difference in the size of the effect or heterogeneity, we mentioned this in the Effects of interventions section and/or presented the findings in a table.

GRADE and 'Summary of findings' table

Using the GRADE approach, at least two review authors (KH/LYC) independently rated the overall certainty of evidence using the GDT tool (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/) for the main comparison pairs listed in the Types of interventions section. The certainty of evidence reflects the extent to which we were confident that an estimate of effect was correct and we applied this in the interpretation of results. There were four possible ratings: 'high', 'moderate', 'low' and 'very low' (Handbook 2011). A rating of 'high' certainty evidence implies that we were confident in our estimate of effect and that further research was very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. A rating of 'very low' certainty implies that any estimate of effect obtained was very uncertain.

The GRADE approach rates evidence from RCTs that do not have serious limitations as high certainty. However, several factors could lead to the downgrading of the evidence to moderate, low or very low. The degree of downgrading was determined by the seriousness of these factors:

study limitations (risk of bias);

inconsistency;

indirectness of evidence;

imprecision;

publication bias.

The 'Summary of findings' tables present the following outcomes:

-

resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear':

at between one week and up to two weeks;

after four weeks;

health‐related quality of life;

ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation;

hearing;

serious complications;

suspected ototoxicity.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

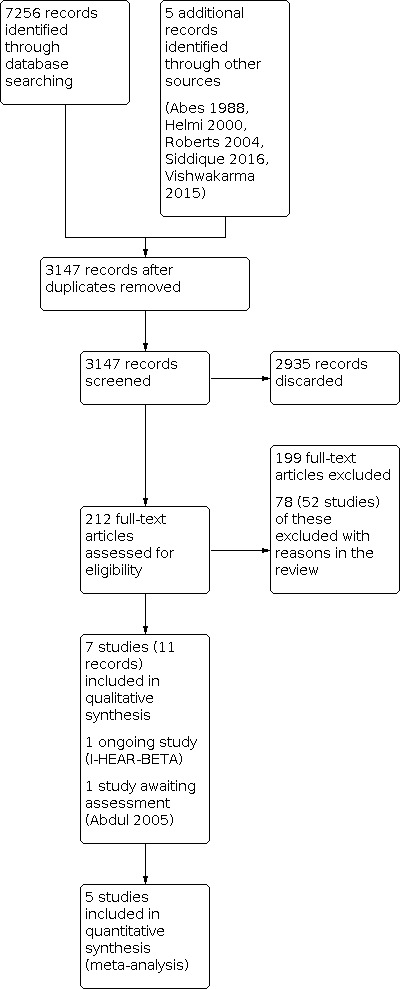

The searches retrieved a total of 7256 references and we identified five additional references from other sources. This reduced to 3147 after removal of duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts and subsequently removed 2935 references. We assessed 212 full texts for eligibility of which we discarded 199 references; we excluded 78 of these references (52 studies) with reasons recorded in the review (see Excluded studies).

We included seven studies (11 references) (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Loock 2012; Macfadyen 2005; van Hasselt 1997; Vishwakarma 2015). The Characteristics of included studies table and Table 7 provide further details of the included studies.

4. Summary of study characteristics.

|

Ref ID (no. participants) |

Setting | Population | Antibiotic | Topical antiseptic | Treatment | Follow‐up | Background treatment | Notes |

| Topical antibiotics versus acetic acid | ||||||||

|

Loock 2012 (159 participants) |

South Africa, city (secondary care) | Patients with otorrhoea because of active mucosal COM Age over 6 years (90% between 20 and 34 years) |

Ciprofloxacin, ear drops, (no concentration), 6 drops/8 hours | 1% acetic acid 6 drops/12 hours |

4 weeks | Up to 8 weeks | Aural cleaning at 1st visit | Part of a 3‐arm trial; third arm used boric acid (see below) |

|

van Hasselt 1997 (58 participants in relevant arms) |

Malawi (community setting) | CSOM (no details) "Children" ‐ no age information provided |

0.3% ofloxacin 3 drops/8 hours |

2% acetic acid in spirit 25% and glycerine 30% 3 drops/8 hours |

2 weeks | 8 weeks | Suction cleaning at the start of trial, at 1‐week and 2‐week follow‐up | Part of a 3‐arm trial; third arm used topical antiseptics + steroids |

| Neomycin 0.5%/polymixin B 0.1%, 3 drops/8 hours | ||||||||

|

Vishwakarma 2015 (100 participants) |

India (secondary care) |

Tubotympanic (safe) type of CSOM Mean age 69 years (range: 10 to 60 years) |

Gentamicin (0.3%), ear drops, 3 drops every 8 hours | Acetic acid (1.5%), ear drops, 3 drops every 8 hours | 2 weeks | 2 weeks | None listed | Resolution of ear discharge measured as symptom score |

| Topical antibiotics versus aluminium acetate (Burow's solution) | ||||||||

|

Fradis 1997 (51 participants, 60 ears) |

Israel (ENT outpatient clinic) | Chronic otitis media Mean: 44.4 years (range 18 to 73 years) |

Ciprofloxacin (no concentration), 15 drops per day |

1% aluminium acetate solution 5 drops/8 hours |

3 weeks | 3 weeks | None mentioned | Randomisation by ear Not possible to use results 3‐arm trial |

| Tobramycin (no concentration), 15 drops per day | ||||||||

| Topical antibiotics versus boric acid | ||||||||

|

Loock 2012 (159 participants) |

South Africa, city (secondary care) | Patients with otorrhoea because of active mucosal COM Age over 6 years (90% between 20 and 34 years) |

Ciprofloxacin, ear drops, (no concentration), 6 drops/8 hours | Boric acid powder Single administration |

4 weeks (antibiotics) | Up to 8 weeks | Aural cleaning at 1st visit | Part of a 3‐arm trial; third arm used acetic acid (see above) |

| Macfadyen 2005 (427 participants) | Kenya, rural (community, school setting) | Children (aged over 5 years) with CSOM Mean age 11.1 ± 3.15 years |

0.3% ciprofloxacin, ear drops, no volume given every 12 hours | 2% boric acid in 45% alcohol, ear drops, no volume given every 12 hours | School days only for 2 weeks | 4 weeks | Daily dry mopping before application | — |

| Topical antibiotics versus povidone‐iodine | ||||||||

| Jaya 2003 (40 participants) | India, city (ENT outpatient clinic) |

Actively discharging CSOM with moderate to large central perforation Age over 10 years (50% between 21 to 21 to 40) |

Ciprofloxacin 0.3% ear drops, 3 drops 3 times daily | Povidone‐iodine 5% solution, 3 drops 3 times daily | 10 days | 4 weeks | Suction cleaning before trial and then daily dry mopping | — |

| Systemic and topical antibiotics versus acetic acid and aural toileting | ||||||||

|

Gupta 2015 (100 participants) |

India (secondary care) |

CSOM Mean age: 36.4 years (range: 6 to 72 years) |

Topical ciprofloxacin (no concentration/volume) daily for 3 months, plus oral ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily for 15 days |

Diluted acetic acid (2 mL) daily. Every second day this was completed at the hospital with suction ear cleaning. Continued until no further discharge |

See details for each treatment arm | 3 months | Dry mopping at 1st visit | — |

We identified one ongoing study (I‐HEAR‐BETAa; see Characteristics of ongoing studies). One reference is awaiting classification (Abdul 2005; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

A flow chart of study retrieval and selection is provided in Figure 1.

1.

Process for sifting search results and selecting studies for inclusion.

Included studies

We included seven studies (11 references) (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Loock 2012; Macfadyen 2005; van Hasselt 1997; Vishwakarma 2015). The Characteristics of included studies table and Table 7 provide a further details of the included studies.

Study design

Three studies were three‐arm trials (Fradis 1997; Loock 2012; van Hasselt 1997). In each case, all three study arms were included in the comparison. Details of the other study arms can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

One study was presented as a non‐peer reviewed report where no mention of randomisation was made (van Hasselt 1997). However, the same study author refers to the study as "randomised" in the introduction of a later publication. The remaining six studies indicated that they were "randomised".

Unit of randomisation

There were no cluster‐randomised trials identified. Fradis 1997 randomised participants by ear, rather than by person, meaning that the 9 (of 51) included participants with bilateral disease may have been given different topical antibiotics for each ear. It is not possible to separate out these participants and so the results cannot be used.

Sample size

A total of 935 participants were included in the seven studies. The number of participants in the studies ranged from 40 to 427.

Location

Three studies were conducted in India (Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Vishwakarma 2015) and three studies were conducted in different African countries: Malawi (van Hasselt 1997), Kenya (Macfadyen 2005), and South Africa (Loock 2012). The final study was conducted in Israel (Fradis 1997).

Setting

Five studies were based in secondary care in the ENT departments of hospitals (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Loock 2012; Vishwakarma 2015). Macfadyen 2005 was completed in primary schools and van Hasselt 1997 was a community study.

Population

Age and sex

The ages of participants are reported in Table 7. One study recruited only children (van Hasselt 1997) and six studies included both adults and children although randomisation did not appear to be stratified by age in any study (Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Loock 2012; Macfadyen 2005; Vishwakarma 2015). Six studies reported that they included both males and females. The percentage of females in the studies ranged from 39% to 65%.

Diagnosis

Main diagnosis

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) was the main diagnosis in all studies (Table 7). None of the studies reported any of the participants having an alternative cause of ear discharge.

Duration of discharge

Three studies did not list the duration of discharge (Loock 2012; van Hasselt 1997; Vishwakarma 2015). Where reported, the information was provided in different ways making comparison difficult. The minimum duration of discharge in Gupta 2015 was four weeks, Macfadyen 2005 reported a median duration of eight weeks and the mean duration of discharge in Fradis 1997 was 24 months. Jaya 2003 provided the most information and identified that 15 participants (37.5%) had symptoms for less than one week, 20 participants (50%) for between one and four weeks, and five participants (12.5%) had symptoms for longer than four weeks. The paper noted that 27 participants (67.5%) had CSOM for more than five years.

Intervention

Details of the interventions, background treatments and treatment durations for each of the included studies are summarised in Table 7. The treatment durations lasted between 10 days and 4 weeks.

Comparisons

The included studies presented information for five comparisons:

Topical antibiotics versus acetic acid: two studies used quinolones (Loock 2012; van Hasselt 1997) and one study used aminoglycosides (Vishwakarma 2015).

Topical antibiotics versus aluminium acetate: one study arm used quinolones and the other used aminoglycosides (Fradis 1997).

Topical antibiotics versus boric acid (either ear drops or a single administration of boric acid powder): two studies both used quinolones (Loock 2012; Macfadyen 2005).

Topical antibiotics versus povidone‐iodine: one study used quinolones (Jaya 2003).

Topical antibiotics and systemic antibiotics (quinolones) versus acetic acid and aural toileting: one study (Gupta 2015).

Outcomes

Resolution of ear discharge

All seven studies reported resolution of ear discharge as an outcome, although the definitions, methods and timing of assessment differed between studies. These are summarised in Table 8

5. Resolution of ear discharge outcome.

| Reference | Unit of randomisation | Discharge results reported by | Definition | Otoscopically confirmed? | Time points | Notes |

| Fradis 1997 | Ear | Ear | "Clinical success" defined as cessation of otorrhoea and eradication of the micro‐organisms in the post‐treatment culture | Unclear | 2 to 4 weeks: 21 days | Not possible to use these results as randomisation by ear (9/51 patients had bilateral disease) |

| Gupta 2015 | Person | Person | "Absence of discharge" | Otoscopically confirmed | 2 to 4 weeks: 15 days After 4 weeks: 1 month |

— |

| Jaya 2003 | Person | Person | "Inactive" ear | Microscopic examination | 1 to 2 weeks: 2 weeks 2 to 4 weeks: 4 weeks |

— |

| Loock 2012 | Person | Person | "Inactive" ear (dry) | Otoscopically confirmed | 2 to 4 weeks: 4 weeks | Also measured patient satisfaction, which asked patients whether their ears were 'completely dry', 'better but not completely dry', 'no better, still running' |

| Macfadyen 2005 | Person | Both by person | Resolution of aural discharge | Otoscopically confirmed | 1 to 2 weeks: 2 weeks 2 to 4 weeks: 4 weeks |

For bilateral disease results were reported for when either ear was dry and when both ears were dry. For this review we have used the 'both ears' results. |

| van Hasselt 1997 | Unclear | Results reported by ear | "Dry ear" | Unclear | 1 to 2 weeks: 1 week 2 to 4 weeks: 2 weeks |

Results not used as it was not possible to account for correlation between ears due to bilateral disease |

| Vishwakarma 2015 | Person | Person | "Clinical cure" defined as a score of < 3 on a symptom scale1 | Unclear | 1 to 2 weeks: 14 days | — |

1Symptom scale; tinnitus: absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3); amount of discharge: absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3); type of discharge: absent (0), mucoid (1), mucopurulent (2), purulent (3). Sum scores in each category to give range of 0 to 9.

Health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument

No studies reported this outcome.

Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation

Three studies reported this outcome, although the definitions are different and the methods of assessment are not always clear. Loock 2012 gave the number of participants who reported unpleasant taste and burning sensation, Vishwakarma 2015 reported one case of "mild irritability" with the use of acetic acid and Macfadyen 2005 recorded "ear pain, irritation, and bleeding".

Hearing

One study presented the average change in hearing (air conduction) from baseline at four weeks as decibels (dB) averaged over 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz (Macfadyen 2005). Four studies noted that audiometry was completed as part of the study but results were either not presented (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015) or only presented narratively (Jaya 2003; Loock 2012). No hearing outcomes were measured or reported in two studies (van Hasselt 1997; Vishwakarma 2015).

Serious complications (including intracranial complications, extracranial complications and death)

Serious complications were not consistently reported. One study reported that no serious complications occurred (Loock 2012).

Suspected ototoxicity

This outcome was not consistently reported. Two studies attempted to record ototoxicity (Jaya 2003; Vishwakarma 2015).

Excluded studies

We excluded 52 studies (78 papers) after reviewing the full text. Further details for the reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The main reasons for exclusion were as follows:

We excluded 47 studies (73 papers) because the comparisons were not appropriate for this review, but were relevant to another review in this suite:

Topical antibiotics (CSOM‐1): Asmatullah 2014; de Miguel 1999; Esposito 1990; Gyde 1978; Jamallulah 2016; Kasemsuwan 1997; Kaygusuz 2002; Liu 2003; Mira 1993; Nawasreh 2001; Ramos 2003; Siddique 2016; Tutkun 1995; van Hasselt 1998a.

Systemic antibiotics (CSOM‐2): de Miguel 1999; Eason 1986; Esposito 1990; Fliss 1990; Ghosh 2012; Legent 1994; Nwokoye 2015; Onali 2018; Picozzi 1983; Ramos 2003; Renuknanada 2014; Rotimi 1990; Sanchez Gonzales 2001; Somekh 2000; van der Veen 2007.

Topical versus systemic antibiotics (CSOM‐3): de Miguel 1999; Esposito 1990; Esposito 1992; Povedano 1995; Ramos 2003; Yuen 1994.

Topical antibiotics with steroids (CSOM‐4): Boesorire 2000; Browning 1988; Couzos 2003; Crowther 1991; Eason 1986; Gendeh 2001; Helmi 2000; Indudharan 2005; Kaygusuz 2002; Lazo Saenz 1999; Leach 2008; Miro 2000; Panchasara 2015; Ramos 2003; Subramaniam 2001; Tong 1996.

Topical antiseptics (CSOM‐5): Eason 1986; Minja 2006; Papastavros 1989.

Aural toileting (CSOM‐7): Eason 1986; Kiris 1998; Smith 1996.

We excluded the remaining five studies (five papers) for the following reasons:

Browning 1983: although the comparison was antibiotics compared with topical antiseptics, the antibiotics were prescribed based on the results of the culture and so no standard antibiotic treatment was given.

Clayton 1990: less than 20% of participants within the study had CSOM.

Roydhouse 1981: the intervention was a mucolytic agent (bromhexine), which was not classified as an antiseptic.

Thorpe 2000: compared three concentrations of the same topical antiseptic (aluminium acetate), which is not a question included in this review.

van Hasselt 1998b: although the comparison was topical antibiotics with topical antiseptics, the antibiotics were given as a single dose, which does not meet the inclusion criteria for this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 for the 'Risk of bias' graph (our judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies) and Figure 3 for the 'Risk of bias' summary (our judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

We judged two studies to be at high risk of bias (Gupta 2015; van Hasselt 1997). Neither study reported methods for sequence generation and Gupta 2015 indicated that participants who were already using antibiotics were allocated to the antiseptic treatment group, which may have created biases between the groups but the baseline characteristics are not provided. For van Hasselt 1997, the original report did not mention randomisation and this was only mentioned in passing as part of the introduction to a different study.

We judged three studies as at unclear risk of bias as they did not provide clear data on how the randomisation schedule was generated (Fradis 1997; Jaya 2003; Vishwakarma 2015). We judged two studies as at low risk as they reported randomisation well (Loock 2012; Macfadyen 2005).

Allocation concealment

We judged the same two studies that are at high risk of selection bias to be at high risk of allocation concealment bias (Gupta 2015; van Hasselt 1997). In Gupta 2015, as there was selection of participants to one of the groups (those using antibiotics to the acetic acid group), we have to assume allocation concealment to have been broken. For van Hasselt 1997, as there were an unequal number of people between the groups (46 versus 38 versus 12) without any explanation, there is a risk of bias due to selective allocation.

We judged Vishwakarma 2015 as at unclear risk of bias as it does not provide information on allocation concealment. We judged three studies as at low risk of bias because they reported measures to protect bias from allocation concealment well (Fradis 1997; Loock 2012; Macfadyen 2005).

Blinding

Performance bias

We assessed two studies to be at high risk of performance bias: Gupta 2015 did not mention blinding and Vishwakarma 2015 reported that the study was an "open study".

We assessed two studies to be at unclear risk of bias. Although Loock 2012 made some attempts to blind participants to treatment, because one of the treatments (boric acid) was given as a powder and the other two as ear drops blinding was not likely to be effective. van Hasselt 1997 did not mention blinding and as one of the treatments was acetic acid ear drops, which have a distinctive smell, blinding would have been difficult.

We assessed three studies as at low risk of bias because they provided sufficient descriptions of how they kept participants and professionals blinded the allocated treatments (Fradis 1997; Jaya 2003; Macfadyen 2005).

Detection bias

Similar to performance bias, we assessed two studies to be at high risk of bias (Gupta 2015; Vishwakarma 2015), two studies as at unclear risk (Loock 2012; van Hasselt 1997) and three studies as at low risk of detection bias (Fradis 1997; Jaya 2003; Macfadyen 2005).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed one study to be at high risk of attrition bias: van Hasselt 1997 reported a high loss to follow‐up (27/96; 28%) despite being a short trial. No reasons were provided and the loss is not balanced across groups, ranging from 8% to 40% of participants by group.

We assessed four studies to be at unclear risk of attrition bias:

Fradis 1997: presented a loss to follow‐up of 10% (6/60) but no reasons were provided or details of to which group the lost participants were allocated.

Gupta 2015: the study does not report any patients dropping out but as the study lasted three months and the participants were advised to visit the hospital every other day its seems unlikely that there was no loss to follow‐up.

Jaya 2003: only four participants (10%) did not provide results; the reasons were not given and these missing data points could have affected the efficacy results due to the small sample size. In particular, it may have been important if they withdrew due to adverse events.

Loock 2012: provided the loss to follow‐up rates in the three treatment groups as 5.8%, 15.1% and 18.5% but did not provide reasons within the paper.

We assessed two studies as at low risk of attrition bias because they reported low dropout rates (Macfadyen 2005; Vishwakarma 2015).

Selective reporting

We assessed one study to be at high risk of publication bias (van Hasselt 1997). It was unpublished and makes reference to longer‐term results that were not found in our searches.

We assessed five studies to be at unclear risk of selective reporting bias (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Loock 2012; Vishwakarma 2015). Four of these studies stated that hearing assessment was completed pre‐ and post‐treatment but either did not report the results or only reported vague narrative statements (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Loock 2012). Vishwakarma 2015 used symptom scales as their primary outcome but failed to provide information on the definition or validation of these scales.

We assessed one study as at low risk of selective reporting bias as it was a well‐reported study (Macfadyen 2005).

None of the studies had protocols identified through our searches of clinical trials registries.

Other potential sources of bias

Funding

Three papers did not provide information about funding (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003) and a further paper declared that there were no funding sources (Vishwakarma 2015).

Two studies were funded through national or international research grants: Loock 2012 was funded by the ENT Society of South Africa, National Health Laboratory Service of South Africa (NHLS) but "received no sponsorship or incentive from manufacturers of any of the treatments used"; Macfadyen 2005 was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant reference number: 056756/Z/99/Z) but the study also declared that "Alcon (Denmark and Belgium) provided the Ciloxan supplies".

It appears that van Hasselt 1997 was funded by the Christian Blind Mission International.

Declaration of interest

Four studies did not make a statement about any interests (Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Macfadyen 2005; van Hasselt 1997), whilst the remaining three either declared that they had no interests (Loock 2012; Vishwakarma 2015) or that they had no financial interests (Jaya 2003).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. Topical antibiotics compared to acetic acid for chronic suppurative otitis media.

| Topical antibiotics compared to acetic acid for chronic suppurative otitis media | |||||||

| Patient or population: chronic suppurative otitis media Setting: secondary care (India, South Africa) Intervention: topical antibiotics Comparison: acetic acid | |||||||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without topical antibiotics | With topical antibiotics | Difference | |||||

| Resolution of ear discharge (1 to 2 weeks) Aminoglycosides assessed with: 'clinical cure' Follow‐up: 14 days |

100 (1 RCT) | RR 0.88 (0.72 to 1.08) | Study population | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | It is very uncertain whether acetic acid is more effective at resolving ear discharge compared with topical aminoglycoside antibiotics at 14 days | ||

| 84.0% | 73.9% (60.5 to 90.7) | 10.1% fewer (23.5 fewer to 6.7 more) | |||||