Abstract

Background

This article describes the second update of a Cochrane review on the effectiveness of laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Previous versions were published in 2006 and 2010 where we also evaluated trials of methylnaltrexone; these trials have been removed as they are included in another review in press. In these earlier versions, we drew no conclusions on individual effectiveness of different laxatives because of the limited number of evaluations. This is despite constipation being common in palliative care, generating considerable suffering due to the unpleasant physical symptoms and the availability of a wide range of laxatives with known differences in effect in other populations.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and differential efficacy of laxatives used to manage constipation in people receiving palliative care.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and Web of Science (SCI & CPCI‐S) for trials to September 2014.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating laxatives for constipation in people receiving palliative care.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors assessed trial quality and extracted data. The appropriateness of combining data from the studies depended upon clinical and outcome measure homogeneity.

Main results

We identified five studies involving the laxatives lactulose, senna, co‐danthramer, misrakasneham, docusate and magnesium hydroxide with liquid paraffin. Overall, the study findings were at an unclear risk of bias. As all five studies compared different laxatives or combinations of laxatives, it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis. There was no evidence on whether individual laxatives were more effective than others or caused fewer adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

This second update found that laxatives were of similar effectiveness but the evidence remains limited due to insufficient data from a few small RCTs. None of the studies evaluated polyethylene glycol or any intervention given rectally. There is a need for more trials to evaluate the effectiveness of laxatives in palliative care populations. Extrapolating findings on the effectiveness of laxatives evaluated in other populations should proceed with caution. This is because of the differences inherent in people receiving palliative care that may impact, in a likely negative way, on the effect of a laxative.

Plain language summary

Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care

Background

People with an incurable illness may receive palliative care, which involves making the person as comfortable as possible by controlling pain and other distressing symptoms. People receiving palliative care commonly experience constipation. This is as a result of the use of medicines (e.g. morphine) for pain control, as well as disease, dietary and mobility factors. There is a wide range of laxatives available. The aim of this review was to determine what we know about the effectiveness of laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care.

Study characteristics

We searched medical databases for clinical trials of the use of laxatives for constipation in people receiving palliative care. Two review authors assessed study quality and extracted data.

Key results and quality of evidence

We identified five studies involving 370 people. The laxatives evaluated were lactulose, senna, co‐danthramer combined with poloxamer, docusate and magnesium hydroxide combined with liquid paraffin. Misrakasneham was also evaluated; this is a traditional Indian medicine and is used as a laxative, containing castor oil, ghee, milk and 21 types of herbs.

There was no evidence on which laxative provided the best treatment. However, the review was limited as the evidence was from only five small trials and patient preference and cost were under evaluated. Further rigorous, independent trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of laxatives.

Background

Description of the condition

This is the second update of a Cochrane review first published in 2006 (Miles 2006), and subsequently in 2010 where trials of methylnaltrexone were also evaluated; these trials have been removed as they are included in another review in press (Candy 2011).

There are many definitions of constipation (Gray 2011). In part, this reflects differences in what is normal; for instance in healthy people the range of bowel evacuations can be from three times a day to three times a week (Thompson 1999). However, in general, definitions of constipation, including the Rome III Criteria (Longstreth 2006), make reference to:

infrequent, difficult or incomplete bowel evacuation that may lead to pain and discomfort;

stools that can range from small, hard 'rocks', to a large bulky mass;

a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

Constipation can generate considerable suffering, including abdominal pain and distension, anorexia, nausea, general malaise and in faecal impaction, an overflow of diarrhoea. It can also cause headaches, halitosis, restlessness and confusion. There are significant psychological and social consequences that can contribute to a reduction in a person's quality of life. The suffering can be so severe that some people with opioid‐induced constipation choose to decrease or even discontinue opioids, thereby preferring to experience inadequate pain control rather than the symptoms of constipation (Thomas 2008).

The causes of constipation can be classified as follows.

Lifestyle‐related, such as having a low‐fibre diet, and a poor fluid intake. Physical inactivity can bring about a reduction in abdominal muscle activity and stimulation producing a 'sluggish bowel' (Winney 1998). In people who are being treated in a healthcare setting, a lack of privacy or environmental factors, or both, such as having to use a bedpan or a commode in a communal area can inhibit bowel function and predispose to constipation in people who are already debilitated.

Disease‐related for mechanical‐anatomical reasons, such as an anal fissure, colitis, diverticular disease, haemorrhoids, hernia and rectocoele. In the common cancers, particularly bowel and ovarian cancer, gastrointestinal symptoms are a frequent complication (Droney 2008; Dunlop 1989). There are also metabolic and physiological consequences of various conditions that increase the tendency for constipation, including paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia, hypokalaemia, obstructed venous outflow with right heart failure and intestinal lymphoedema.

Drug‐induced, there is a wide range of drugs that have constipation as an adverse effect. These drugs include neurotoxic chemotherapy agents, antiemetics, anticholinergics and diuretics. Good palliative care is predicated on a need to achieve optimal pain control; many of the drugs used to achieve this, such as opioids, cause constipation.

Constipation is a common problem in palliative care, where the overall estimated incidence ranges, depending on the definition of constipation used, from 18% to 90% of people (Clark 2012; Laugsand 2009; Sykes 1998). The causes in this population are often multifactorial relating to poor dietary intake, physical inactivity, disease and treatment related. For people receiving palliative care receiving opioid treatments, the estimates of the incidence of constipation are even higher: from 72% (Droney 2008) to 87% of people (Sykes 1998).

Description of the intervention

Prevention and management of constipation relates to cause. People receiving palliative care are at risk of developing constipation as a result of changes in their lifestyle. These are attributable to disease progression and are unlikely to be readily resolved. However, given that constipation for the majority of people receiving palliative care has the potential to be drug‐induced, management to promote satisfactory bowel movements commonly involves some form of pharmaceutical administration, of which the first line of recommended treatment is commonly a laxative (Caraceni 2012; NICE 2012; Scottish Palliative Care Guidelines 2014).

There is a wide range of laxatives that work by softening faecal matter or through direct stimulation of peristalsis, or both. Laxatives are generally classified according to their mode of action: bulk‐forming laxatives, osmotic laxatives, stimulant laxatives, and faecal softeners and lubricants. Widely used laxatives are the stimulant preparations: these include senna, bisacodyl, sodium picosulfate and wheat bran. In a survey in Spain, the most commonly prescribed was lactulose (Noguera 2010). The authors suggest this is because of ease of dosing, its sweet taste and that it is often freely available through prescription, thereby requiring less financial burden to the person.

How the intervention might work

Laxatives work in various ways. Bulk‐forming laxatives involve the absorption of large amounts of fluids. This incurs a stretch reflex on the intestinal wall, which results in reflexive, propulsive activity, leading to bowel movement. These types of laxatives are not ordinarily recommended in palliative care, as people may not maintain a necessary adequate fluid intake to avoid intestinal obstruction or faecal impaction. Osmotic laxatives increase water content and thereby the softness and volume of the stool. Besides lactulose, osmotic laxatives include polyethylene glycol, sorbitol and magnesium citrate. Stimulant laxatives induce propulsive motility. Individually, within these mode of action groups, laxatives work in different ways.

Bisacodyl works after bacterial hydrolysis in the intestines.

Sodium picosulfate and senna only after hydrolysis in the large intestine (colon).

Lactulose is fermented in the intestine producing carbon dioxide and hydrogen, which results in acidification of the stool. Due to irritation of the colon wall this promotes peristalsis (Droney 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

Laxatives are an accepted treatment in constipation. Reviewing the evidence base to support their use is necessary to compare and assess individual laxatives in terms of effect and harm, as well as a person's preference and cost. There are published clinical practice recommendations in palliative care that have been informed by earlier versions of this review including those from the European Palliative Care Association (Caraceni 2012). It is timely to update this review as the last search was undertaken in 2010.

It is important to highlight that there are other reviews on laxatives in other populations that have identified multiple trials, of note is one Cochrane review on lactulose in comparison with polyethylene glycol for chronic constipation (Lee‐Robichaud 2010). This review concluded on the basis of evidence from 10 trials that polyethylene glycol should be used in preference to lactulose. In extrapolating them to a palliative care population, these results must be treated with care as they came from studies whose populations are different. Moreover, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of laxatives in palliative care populations, because of the differences inherent in this group that may impact, in a likely negative way, on the effect of a laxative. In particular, the multifactorial pathophysiology of constipation in people with advanced disease. This includes but is not limited to the impact of disease progression, that certain terminal illnesses have a rapid course, that people may have from co‐morbidities, have multiple organ failure, have increasing frailty, reduced liquid and food intake, and may be receiving various treatments including multiple different drugs (Bader 2012; Sanderson 2014). People receiving palliative care may also have a higher risk than other populations of experiencing adverse effects from the laxatives used.

Sincethe mid‐2000s, mu‐opioid antagonists, such as methylnaltrexone have been developed and have been recommended as an alternative to laxatives. These drugs are generally only recommended when traditional laxatives have failed (Caraceni 2012; Scottish Palliative Care Guidelines 2014). A separate Cochrane review on mu‐opioids antagonists in people receiving palliative care is in press.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and differential efficacy of laxatives used to manage constipation in people receiving palliative care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the efficacy of laxatives were included.

We applied no language restrictions and allowed both published and unpublished studies.

Types of participants

Eligible studies concerned adults receiving palliative care who were given a laxative, either as a prophylactic or because they were constipated. These studies could be undertaken in any care setting (inpatient, outpatient, day‐care, community).

We also included studies of people whose disease was described as advanced or end‐stage irrespective of care setting.

We excluded studies that included healthy volunteers, participants with constipation as a result of drug misuse and participants with constipation arising from bowel obstruction.

Types of interventions

All laxatives were eligible for inclusion. This was irrespective of routes of administration (oral, rectal or another route) and for doses that were evaluated in the management of constipation in palliative care for cancer and other life‐limiting progressive diseases. Laxatives included, for example, senna and lactulose. The comparator could be placebo, usual care or another active intervention such as a study of comparison between two laxatives.

Types of outcome measures

Studies were eligible if the outcome measures were reported in terms of relief of constipation. These could include:

laxation response, such as change in frequency of defecation and ease of defecation;

relief of systemic and abdominal symptoms related to constipation, such as an reduced appetite, abdominal pain and distension, and confusion;

change in quality of life;

need for additional laxatives, as in the use of 'rescue' laxatives, such as a rectal suppository or an enema; and

acceptability and tolerability including participant preference.

We collected information on adverse effects, including:

nausea/vomiting;

pain;

flatus;

diarrhoea; and

faecal incontinence.

Primary outcomes

Laxation response. Laxation response could be measured by reporting the time to a bowel movement or frequency of having a bowel movement. It could be by the need for an additional laxative beyond those that were evaluated in the trial or measured by whether the person had difficulty or completeness of defecation. The type of stool passed, such as in volume and consistency, could also be measured by the Bristol Stool Chart (Lewis 1997).

Adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Participant preference.

Relief of other constipation‐associated symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite.

Search methods for identification of studies

The aim of the search strategy was to be as comprehensive as possible. We updated our 2014 review search strategy as in earlier versions using three approaches: a literature search for recent reviews, expert consultation and a search of the British National Formulary.

Electronic searches

We used both English and American spellings and names. Searches were restricted to human participants. The subject search used a combination of controlled vocabulary and free‐text terms based on a strategy for searching MEDLINE. Appendix 1 details the search strategies used for this current update. We did not seek studies pre‐dating 1966.

For this update, we searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), Issue 8 of 12, 2014.

MEDLINE (OVID) August 2010 to 9 September 2014.

EMBASE (OVID) August 2010 to 9 September 2014.

CINAHL (EBSCO) August 2010 to September 2014.

Web of Science (SCI & CPCI‐S) 2010 to September 2014.

Previously, for the original review and the first updated version, the following was searched up to 2010 unless otherwise stated:

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library Issue 8, 2010).

MEDLINE search from 1966 to January 2005 ‐ (update to August 2010).

EMBASE search from 1980 to January 2005 ‐ (update to August 2010).

CANCERLIT from 1980 to March 2001.

Science Citation Index from 1981 to March 2005.

Web of Science March 2005 to August 2010.

CINAHL from 1982 to March 2005 (update to August 2010).

Databases that provide information on grey literature: SIGLE from 1980 to 2005 (containing British Reports, Translations and Theses), NTIS, DHSS‐DATA and Dissertation Abstracts from 1961 to 2005, and Index to Thesis to October 2010.

Conference proceedings from both international and national conferences were handsearched and databases on conference proceedings were accessed ‐ Boston Spa Conferences (containing Index of Conference Proceedings) and Inside Conferences 1996 to 2001, Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings from 1982 to 2005. In addition, conference proceedings for the European Association of Palliative Care 2007 to 2010 were handsearched.

National Health Service National Research Register (containing Medical Research Council Directory) (inception to 2007).

Searching other resources

Reference searching

We searched the MetaRegister of controlled trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct), clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) to October 2014. We also searched reference lists and undertook a forward citation check of all included studies. We also searched reference lists from relevant review articles and sought contact with representatives of pharmaceutical companies for further trial evaluations.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

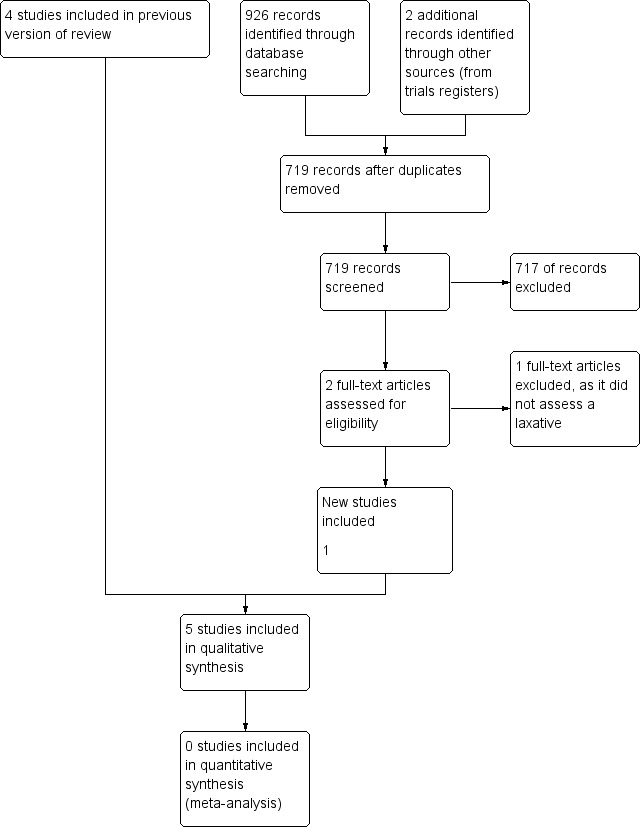

Two review authors (BC/LJ or BC/PL) independently screened citations identified in our searches for eligibility. If it was not possible to accept or reject a study with certainty, we obtained the full text of the study for further evaluation. Two review authors independently assessed studies in accordance with the above inclusion criteria. We resolved any differences in opinion by discussion. We included a PRISMA study flow diagram (Moher 2009), to document the screening process, as recommended in Part 2, Section 11.2.1, of the Cochrane Handbook on Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction form specifically for the review. If possible, we obtained the following information for each of the eligible studies:

study methods (trial design, duration, allocation method, blinding, setting, study inclusion criteria);

participants (number, age, sex, drop‐outs/withdrawals);

laxative(s) (type, dose(s), route of delivery, control used);

outcome data including laxation response;

tolerance and adverse effects.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors assessed the quality of included RCTs according to the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where differences of opinion existed, we resolved them by consensus with the other review authors. We assessed five main sources of systematic bias for each included study.

Randomisation allocation sequence generation.

Concealment of allocation sequence.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors.

Level of completeness of outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

We assessed each domain by whether the criteria for that domain had been met (i.e. low risk of bias), whether they had not (i.e. high risk of bias) or whether it was judged 'unclear' because of insufficient reporting.

Based on these criteria, we categorised a trial as:

low risk of bias if all quality criteria met;

unclear risk of bias if one or more of the criteria was judged as unclear;

high risk of bias if one or more criteria not met.

Measures of treatment effect

We report study results organised by type of intervention treatments evaluated.

We measured treatment effects using dichotomous data, an ordinal rating scale or qualitative evidence.

Dichotomous data

Where dichotomous data were reported, we generated odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also calculated the risk difference (RD), which is the absolute difference in the proportions in each treatment group.

Continuous data

We assessed effects measures for ordinal data as continuous data. We generated the mean difference (MD) for continuous and ordinal data where the data were provided as a mean and standard deviation (SD).

If baseline data were reported pre‐intervention and post‐intervention, we reported means or proportions for both intervention and control groups and calculated the change from baseline. For cross‐over trials, we only generated, as appropriate, an OR or MD for pre‐cross‐over results.

If limitations in the study data prevented reporting an OR, RD or, if continuous data, an MD, we reported the results with caution due to lack of transparency of the evidence.

Qualitative evidence

We planned if there had been any qualitative data reported in the included studies to extract it in consultation with the Cochrane Qualitative Methods Group. Such qualitative data may aim to capture the participant's views on the value of the intervention.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to seek statistical advice if we had identified trials using a cluster design (in which participants were randomly assigned at group level).

Dealing with missing data

Given the nature of this field, there was a significant amount of missing data as a result of trial attrition due to the death of the participant.

Where data were not reported we attempted to contact study authors. For studies using continuous outcomes in which SDs were not reported, and no information was available from the authors, we calculated the SDs using the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Assessment of heterogeneity

If meta‐analysis had been possible, we would have assessed statistical heterogeneity between the studies using the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (we considered a Chi2 P value of less than 0.05 or an I2 value of 50% or more than to indicate substantial heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to explore publication bias using funnel plots.

Data synthesis

Where study data were of sufficient quality and sufficiently similar (in diagnostic criteria, intervention, outcome measure, length of follow‐up and type of analysis), we planned to combine data in a meta‐analysis to provide a pooled effect estimate. We would have used a fixed‐effect model in the first instance. If there was no statistical heterogeneity, we would have used a random‐effects model to check the robustness of the fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If heterogeneity had been identified in a meta‐analysis, we planned to undertake subgroup analysis to investigate its possible sources.

To explore clinical heterogeneity and investigate the effect modification of specific participant characteristics that have been identified in general palliative care populations as effect modifiers, we planned to exclude studies of a higher risk of bias from subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

If sufficient studies were available, we planned to perform, in a meta‐analysis, sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of:

publication status by excluding unpublished studies;

study quality by excluding studies that had a high risk of bias;

validated measures of outcome effect by excluding studies that did not use validated measures.

'Summary of findings' tables

We had planned to use the GRADE system to assess the quality of the evidence associated with specific outcomes (e.g. pain reduction, quality of life improvement, adverse effects) (Schünemann 2008), and construct a 'Summary of findings' table using the GRADE software. Although the review authors note that it is possible to create a 'Summary of findings' table despite the lack of meta‐analysis, because the search found of the small cohort of heterogeneous trials comprising of different laxatives and outcomes, we did not construct a 'Summary of findings' table as it would not add any meaning for the reader.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

From the searches undertaken for the earlier versions of this review we identified three published trials (Agra 1998; Ramesh 1998; Sykes 1991a). We also identified a fourth relevant, but unpublished, study (Sykes 1991b). We excluded 20 studies that had warranted further consideration. They were mostly excluded as they were evaluating the effect of laxatives in a non‐palliative care population.

The 2014 update search identified 717 unique citations (of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL and Web of Science databases) of which one trial was included (Tarumi 2013). We excluded a further study that had warranted further consideration at full text as it was evaluating laxatives in a non‐palliative care population. We also identified two ongoing trials that may fit inclusion criteria when completed (NCT01189409 2014; NCT01416909 2014). In total, we reviewed five RCTs in this update. Figure 1 charts the project progress from screening to inclusion.

1.

Study flow diagram for update search in 2014.

Included studies

The five RCTs analysed 370 participants (Agra 1998; Ramesh 1998; Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b; Tarumi 2013). Two studies were of cross‐over design (Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b); the others were parallel design. The studies were undertaken in Canadian, British, Spanish and Indian populations. All participants were at an advanced stage of disease and were cared for within a palliative care setting. All participants had a cancer diagnosis, apart from four participants (5% of sample) in one study (Tarumi 2013). The mean age of participants ranged from 61 to 75 years. The laxatives evaluated were all taken orally, they were senna (Agra 1998; Ramesh 1998; Sykes 1991a; Tarumi 2013); lactulose (Agra 1998; Sykes 1991a); co‐danthramer plus poloxamer (Sykes 1991a); magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin (Sykes 1991b), and docusate (Tarumi 2013). One study also evaluated the effect of misrakasneham (Ramesh 1998), a drug used in traditional Indian medicine as a purgative, containing castor oil, ghee, milk and 21 types of herbs. We identified no studies of interventions given rectally.

Study comparisons were mostly between different laxatives, others involved an active control of a placebo plus a common laxative. Two studies used in one or both arms a combination of laxatives; senna plus lactulose (Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b), and magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin (Sykes 1991b). Another study used an active control of placebo and senna (Tarumi 2013). All studies measured laxation response and adverse effects. Commonly, laxation response was captured by self report and was assessed at several time points over one or two weeks. Timing of follow‐up was not clear in two studies (Ramesh 1998; Sykes 1991a). None of the studies reported significant baseline differences between the trial arms.

Excluded studies

We excluded 21 studies after assessing full‐text publications, reasons for exclusion included not a trial, outcomes not on laxation or intervention was not a laxative. See table on Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

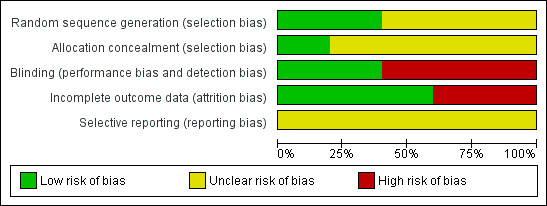

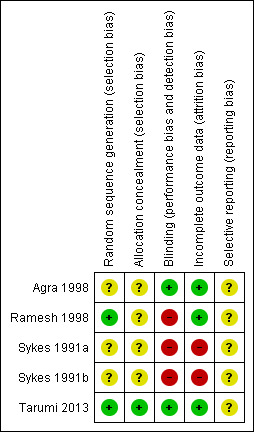

All trials under‐reported key design features. Much of the information from the studies was of an unclear risk of bias. See Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Two studies described how they generated random allocation (Ramesh 1998; Tarumi 2013), and three studies did not describe how they generated the random allocation to trial arms (Agra 1998; Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b). Only one of the studies reported the methods used to conceal random allocation (Tarumi 2013).

Blinding

Owing to differences in the physical characteristics of the intervention laxative and comparison, blinding was not possible in four of the trials, (Agra 1998; Ramesh 1998; Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b). Complete details on who was blinded were provided by one study (Tarumi 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition rates were provided by all studies. Three studies were are a low risk of attrition bias; over three‐quarters of participants completed the studies and the numbers and reasons for dropping out were similar in trial arms (Agra 1998; Ramesh 1998; Tarumi 2013). The other studies were at a higher risk of attrition bias as higher proportions of participants dropped out, 49% in one (Sykes 1991a) and 64% in the other (Sykes 1991b). In these two studies, no participants dropped because of inefficacy and one participant in one trial dropped out because of stomach cramps associated with taking the intervention laxatives of lactulose with senna (Sykes 1991b).

Selective reporting

It is unclear if any of the studies were at risk of reporting bias as there was insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'High risk'.

Other potential sources of bias

The two cross‐over studies did not involve, between the different interventions, a washout period when the participants did not receive any active trial treatment (Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b). Washout is intended to prevent continuation of the effects of the trial treatment from one period to another.

Effects of interventions

Co‐danthramer plus poloxamer versus senna plus lactulose

One cross‐over study of 51 participants evaluated the effectiveness of co‐danthramer plus poloxamer versus senna plus lactulose (Sykes 1991a). Both laxatives were in a liquid format. Neither dosage nor details of the data analyses were reported in full. The study analysed laxation response according to opioid use. Table 1 details findings reported.

1. Co‐danthramer plus poloxamer versus senna plus lactulose.

| Outcome or subgroup | Participants | Effect estimate* |

| Bowel movements in participants receiving strong opioid analgesia (taking ≥ 80 mg) | 17 | "Lactulose plus senna was associated with significantly higher frequency (regardless of which laxative taken first) (P value = < 0.01)" |

| Bowel movements in participants receiving opioid analgesia (< 80 mg) or no opioid analgesia | 21 | "No statistical difference between the trial arms" |

| No bowel movement in treatment week | Unclear | While participants were receiving co‐danthramer plus poloxamer, this occurred 11 times versus once in senna plus lactulose group (P value = 0.01) |

| Suspension of laxative therapy for 24 hours | Unclear | Occurred more frequently with lactulose plus senna (15 cases) than co‐danthramer plus poloxamer (5 cases) (P value = 0.05) |

| Rescue laxatives | Unclear | 14 participants received a rescue laxative only while taking co‐danthramer plus poloxamer but not with senna plus lactulose. 4 participants received rescue laxatives while taking senna plus lactulose but not with co‐danthramer plus poloxamer. 5 participants received rescue laxatives both while taking both trial treatments |

| Participant assessment of bowel function | Unclear | The reported mean change in participant assessment of their bowel function was not significant between drugs at the first week prior to cross‐over or in the week following cross‐over |

| Participant preference | 58 | "While favourable comments about agents effectiveness and flavour were evenly shared, twice as many patients disliked the flavour of co‐danthramer as that of lactulose with senna" |

| Diarrhoea | Unclear | "...diarrhoea resulted in the suspension of laxative therapy occurred more frequently with lactulose and senna compared to co‐danthramer (15 versus 5)" |

| Adverse effects | Unclear | 2 participants reported per‐anal soreness and burning on co‐danthramer plus poloxamer |

| Overall finding | ‐ | Outcomes were mixed on laxation response |

* If data available and appropriate effect estimate was presented as an odds ratio (OR) or a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). If not available or appropriate then effect was reported as stated in the trial.

Laxation response

The trialists report that the 17 participants receiving 80 mg or more of a strong opioid analgesia (either diamorphine or morphine) "had a significantly higher stool frequency when taking lactulose plus senna than while receiving co‐danthramer, P < 0.01". The study reported no statistical difference for the other participants receiving either a lower dose of opioid or no opioid. For participants' assessments of bowel function, they reported no statistical difference between laxatives.

Need for additional laxatives

Nineteen participants required rescue laxatives in the co‐danthramer plus poloxamer group and nine in the senna plus lactulose group.

Constipation‐associated symptoms

The study did not evaluate constipation‐associated symptoms.

Acceptability and tolerability

Diarrhoea resulted in suspension of laxative therapy for 24 hours for 15 participants while taking senna plus lactulose and for five participants while taking co‐danthramer plus poloxamer. The trialists reported that six instances of diarrhoea occurred at opioid doses of at least 80 mg/day while taking senna plus lactulose and none occurred while taking co‐danthramer plus poloxamer. Two participants reported perianal soreness and burning while taking co‐danthramer plus poloxamer. Participant preference was similar between the trial arms (15 for senna plus lactulose and 14 for co‐danthramer plus poloxamer), although they reported more participants disliked the flavour of co‐danthramer plus poloxamer compared with senna plus lactulose.

Magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin versus senna plus lactulose

One unpublished cross‐over trial involved 118 participants (Sykes 1991b). It evaluated the effectiveness of

one week of magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin (mean dose per cross‐over group 45 mL if taken in first week and 49 mL daily if taken in second week), versus

one week of senna plus lactulose (mean dose per cross‐over group of 34 mL if taken in the first week and 38 mL daily if taken in the second week).

Forty‐two of the 118 participants completed the trial. Results were not analysed in terms of whether different opioid doses influenced laxative results. Table 2 details findings.

2. Magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin versus senna plus lactulose.

| Magnesium hydroxide plus liquid | Participants | Effect outcome* |

| Laxation response | 35 | "For all patients and for the subgroups who either were or were not receiving strong opioids there was no statistical difference in stool frequency between the two trial treatment groups". At the end of the trial, 19/35 (54%) participants had bowel function they accepted as normal |

| Treatment failure | 29 | 2 participants passed no spontaneous stool with either treatment |

| Loose stools | unclear | There was no significant difference between treatments in the proportion of participants reporting loose stools |

| Rescue laxatives | unclear | "...rectal measures were used on ten occasions during treatment with senna plus lactulose and 23 occasions while magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin was being used" |

| Participant assessment of constipation | 35 | OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.28 to 4.26** |

| Participant assessment of diarrhoea | 35 | OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.10 to 4.58** |

| Participant assessment of normality of bowel function | 35 | OR 1.11; 95% CI 0.29 to 4.21** |

| Participant preference | 32 | 8/32 (magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin) versus 19/32 (senna and lactulose group) |

| Adverse events | Unclear | In both groups, 1 participant found the treatment intolerably nauseating. 1 participant had gripping abdominal pain with lactulose and senna |

| Overall finding | ‐ | No difference in laxation response |

* If data available and appropriate effect estimate was presented as an odds ratio (OR) or a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). If not available or appropriate then effect was reported as stated in the trial. **Effect outcome used data prior to cross‐over.

Laxation response

No difference was reported in laxation response between the cross‐over groups. The findings did not change by dose of opioid or by the order given in the cross‐over of senna plus lactulose with magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin. They reported that the dosage of magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin required to achieve the same frequency of bowel movements was significantly higher than the dosage required with senna plus lactulose. Using data from the pre‐cross‐over week, there was no significant difference in participants' perception of being constipated, or normality of bowel function. At the end of the trial, 54% of participants considered their bowel movements were normal.

Need for additional laxatives

Participants in both groups required rescue laxatives. They reported that a significantly greater proportion of participants needed rescue laxatives while taking senna plus lactulose compared with magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin.

Constipation‐associated symptoms

The study did not evaluate constipation‐associated symptoms.

Acceptability and tolerability

There was no significant difference between treatments in participants reporting diarrhoea. In both groups, one participant found the treatment intolerably nauseating. One participant, while taking senna plus lactulose, experienced gripping abdominal pain. More participants preferred senna plus lactulose rather than magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin.

Misrakasneham versus senna

One small study of 36 participants evaluated the effectiveness of up to 10 mL of misrakasneham versus senna 24 to 72 mg (both in liquid format) over two weeks (Ramesh 1998). Participants in the trial were taking various doses of morphine but results were not analysed in terms of whether different opioid dose influenced laxative results. Table 3 details the findings.

3. Misrakasneham versus senna.

| Outcome or subgroup | Participants | Effect estimate* |

| Satisfactory bowel movements with no adverse effects | 28 | OR 7.67; 95% CI 0.37 to 158.01 |

| Overall finding | ‐ | No difference in laxation response |

* If data available and appropriate effect estimate was presented as an odds ratio (OR) or a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). If not available or appropriate then effect was reported as stated in the trial.

Laxation response

There was no statistical difference between the misrakasneham and the senna groups in satisfactory bowel movements (defined as the comfortable feeling that a person experienced after having a free, effortless bowel movement at a frequency acceptable to him or her).

Need for additional laxatives

Six participants required rescue laxatives, five of whom were in the senna group.

Constipation‐associated symptoms

The study did not evaluate constipation‐associated symptoms.

Acceptability and tolerability

Nausea, vomiting and colicky pain were reported by two participants taking misrakasneham. None of the participants withdrew because of inefficiency. Participant preference was split between the groups.

Senna versus lactulose

One study of 75 participants evaluated the effectiveness of lactulose 10 mg to 40 mg versus senna 12 mg to 48 mg (both laxatives were in liquid format) over four weeks (Agra 1998). Doses of the laxatives were increased according to clinical response; the study authors do not provide details on mean doses. Results were not analysed in terms of whether different opioid doses influenced laxative results. Table 4 details the findings.

4. Senna versus lactulose.

| Outcome or subgroup | Participants | Effect estimate* |

| Mean number of defecation days | 75 | MD ‐0.10; 95% CI ‐0.60 to 0.40 |

| Defecation‐free days | 75 | MD 0.00; 95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.48 |

| General state of health | 75 | MD ‐0.10; 95% CI ‐0.31 to 0.11 |

| Overall finding | ‐ | No difference in laxation response |

* If data available and appropriate effect estimate was presented as an odds ratio (OR) or a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). If not available or appropriate then effect was reported as stated in the trial.

Laxation response

There was no statistical difference between the senna and the lactulose groups in laxation response, in defecation‐free periods and in the mean number of defecation days (senna: mean 8.9 days, SD 6.6; lactulose: mean 10.6 days, SD 7.3).

Need for additional laxatives

Thirty‐seven per cent of participants completing the study required combined lactulose and senna to relieve constipation.

Constipation‐associated symptoms

There was no statistical difference in the general state of health of the participants between the trial arms.

Acceptability and tolerability

An equal number of participants, three per trial group, reported diarrhoea, vomiting and cramps. There was no significant difference in the number of participants who dropped out between the trial arms. Participant preference was not evaluated.

Docusate plus senna versus placebo plus senna

One study of 74 participants evaluated docusate plus senna (sennosides) versus an active control of placebo plus senna over 10 days (Tarumi 2013). Details of the data analyses were not reported in full. Results were not analysed in terms of whether different opioid doses influenced laxative results. Table 5 details the findings.

5. Docusate plus senna versus placebo plus senna.

| Outcome or subgroup | Participants | Effect estimate* |

| Stool frequency | 56 | No statistically significant difference in the overall mean number of bowel movements per day between the docusate plus senna (x statistic = 0.74 (SD 0.47) and placebo plus senna groups (x statistic = 0.69, SD 0.37) (P value = 0.58) |

| Bowel movement on ≥ 50% of days | 56 | OR 0.52; 95% CI 0.17 to 1.57 |

| Stool volume | 56 | Trialists reported no significant difference between trial arms in stool volume (P value = 0.06) |

| Stool consistency | 56 | Using the Bristol Stool Form Scale, more participants in the placebo plus senna group had Type 4 (smooth and soft) and Type 5 (soft blobs). In the docusate plus senna group, more participants had Type 3 (sausage, cracks in surface) and Type 6 (mushy stool) (P value = 0.01) |

| Participants' perceptions of the difficulty and completeness of defecation | 56 | No differences in reported difficulty in evacuation (13/40 in the docusate group versus 14/56 in the placebo group; OR 1.44; 95% CI 0.59 to 3.54). No difference in sense of completeness of evacuation (25/34 in the docustate plus senna group versus 44/56 in the placebo plus senna group ; OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.28 to 2.05) |

| Overall finding | ‐ | No difference in laxation response |

* If data available and appropriate effect estimate is presented as an odds ratio (OR) or a mean difference (MD). If not available or appropriate then effect is reported as stated in the trial. SD: standard deviation.

Laxation response

The study reported no statistical difference in laxation between docusate plus senna and placebo plus senna. This was in volume, difficulty and completeness of defecation, and having a bowel movement on 50% of the study days (where for instance the OR was 0.52 (95% CI 0.17 to 1.57)). Using the Bristol Stool chart, there was a significant difference (P value = 0.001) in stool consistency between the trial arms; with more participants in the placebo plus senna group having Type 4 (smooth and soft) or Type 5 (soft blobs) stools, and more participants in the docusate plus senna group having Type 3 (sausage like) or Type 6 (mushy) stools.

Need for additional laxatives

At least one type of additional laxative was given to 74% of participants in the placebo plus senna group and 68.6% of participants in the docusate plus senna group. The difference was not significant (P value = 0.77).

Constipation‐associated symptoms

The study measured symptoms, such as shortness of breath and drowsiness, using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. They report no significant difference between the trial arms.

Acceptability and tolerability

Twenty‐five participants in the docusate plus senna group and eight in the placebo plus senna group dropped out; reasons for attrition were not related to the treatments. Adverse effects were not reported. Preference was not measured.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review is the second update of a Cochrane review on the effectiveness of laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. Previous versions were published in 2006 and 2010 where we also evaluated trials of methylnaltrexone; we have removed these trials as they are included in another review in press. This current review sought to determine the effectiveness of the administration of laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. We included five studies, four of which were identified in the earlier review. Studies either compared the effectiveness of two different laxatives, or compared the laxative with an active control.

No differences in effectiveness were demonstrated in:

lactulose compared with senna;

senna plus lactulose compared with magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin;

misrakasneham compared with senna;

docusate plus senna compared with placebo plus senna.

In one study, there were mixed findings on senna plus lactulose compared with co‐danthramer plus poloxamer (Sykes 1991a). There was a significant difference (P value <0.01) in the subgroup of 17 participants receiving strong opioid analgesia that favoured senna plus lactulose compared with co‐danthramer plus poloxamer in stool frequency and overall participants took fewer rescue medications (9/51 in senna plus lactulose group compared with 19/51 in co‐danthramer plus poloxamer group). However, there was no difference between the laxatives in participants' overall assessment of their bowel function.

Four studies report that a few (one to three) participants experienced adverse effects. The most common adverse effects were nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. In the study comparing senna plus lactulose with magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin, one participant from each group withdrew because of intolerable nausea and gripping abdominal pain.

Participant preferences were reported in two studies; one study showed a preference for senna plus lactulose over magnesium hydroxide plus liquid paraffin (Sykes 1991b). The other study found no difference in preference between misrakasneham and senna (Ramesh 1998).

In all included studies, a number of participants remained constipated and were given rescue laxatives. None of the studies explored differences between responders and non‐responders in follow‐up characteristics, such as disease progression or drug use (in particular opioids).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our review findings are limited. The studies were few, and were overall of unclear risk of biased findings. The studies involved small sample sizes and the two cross‐over trials did not involve a washout period between testing the effect of the different treatments. There was limited overlap in which laxative was evaluated, this prevented their results being combined in an analysis. Participant preference was under‐explored. Only one new trial was completed since the last search in 2010. However, there is perhaps little incentive for pharmaceutical companies to sponsor evaluations in established treatments such as laxatives and in the relatively small group of people in palliative medicine (Bader 2012). Laxatives are extensively used in this patient group but there remains little known about the differences in effect and adverse events between the laxatives available. It is unknown whether some laxatives may be more suitable for certain people receiving palliative care than other people.

Quality of the evidence

There were issues in the quality of the evidence. Sample sizes of most studies (four of five) were likely to be under‐powered to find a true effect as they involved fewer than 100 participants. Studies also had some methodological limitations; in three studies, double‐blinding was not possible because the drugs differed in presentation (Ramesh 1998; Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b); in two studies, there was a high attrition rate of over 50% (Sykes 1991a; Sykes 1991b). However, given this was a palliative care population, attrition of this magnitude is not unusual.

Potential biases in the review process

We limited inclusion to studies that specified that their participants were in palliative care or at an advanced stage of a disease. This is likely to have led to a loss of data, as studies we excluded may have included people with advanced disease but the authors did not provide details on disease stage.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There is one larger Cochrane review on laxatives, which is within the general adult population (Lee‐Robichaud 2010). It sought to determine whether lactulose or polyethylene glycol is more effective at treating chronic constipation and faecal impaction. The authors were able to combine the findings of some of the 10 eligible trials in various meta‐analyses. They found that polyethylene glycol was better than lactulose in outcomes of stool frequency and form, and the need for rescue laxatives.

No trials of polyethylene glycol were identified in people receiving palliative care. The findings from reviews in non‐palliative care populations are informative. However, it is important to evaluate laxatives in palliative care populations because of the differences inherent in this group that will impact, in a likely negative way, on the effect of a laxative. In particular, people receiving palliative care may differ from other populations in regards to the multifactorial pathophysiology of constipation, the rapid course of their illness, the presence of multiple organ failure, increased frailty, reduced food intake and higher rates of polypharmacy. People receiving palliative care may also have a higher risk of adverse effects (Bader 2012).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In this second update, the conclusions on the effectiveness of laxatives remain unchanged.

The review cannot provide any information on what may be the optimal laxative management for constipation in people receiving palliative care. The randomised controlled trials included in this review did not show any differences in effectiveness of three commonly used laxatives; senna, docusate and lactulose. However, these studies are subject to bias and low power. None of the studies evaluated the effectiveness of polyethylene glycol in this population.

Implications for research.

Rigorous and independent randomised controlled trials measuring standardised and clinically relevant outcomes in a clearly defined population are needed to establish the effectiveness of laxatives in the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care. To help distinguish between different laxatives there is a need to include measures on tolerability, quality of life, participant preference and costs.

High attrition rates in the included studies and the relatively small numbers of eligible participants in any one palliative care unit suggest that any trial of laxative efficacy should be multicentred.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 December 2019 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2002 Review first published: Issue 4, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 November 2014 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This update includes only trials of laxatives in palliative care. The previous version included both laxatives and methylnaltrexone. Another review specifically on mu‐opioid antagonists for patients in palliative care will include the trials on methylnaltrexone which were included in the earlier version of this review. The conclusion on laxatives have not been changed, but we recommend readers of the previous version to re‐read this update. |

| 21 November 2014 | New search has been performed | A new search for trials on laxatives was undertaken in September 2014; one new trial was identified. |

| 6 July 2011 | Amended | Amendment to contributors of Feedback submitted for Issue 6, 2011. |

| 11 May 2011 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback was received and the author has responded. Please see the Feedback section in the review for details. |

| 6 December 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The background and methods were updated, three new studies were added to the review (Portenoy 2008; Slatkin 2009; Thomas 2008), and the conclusions were revised to include Methylnaltrexone. The review was updated by a new set of authors. |

| 20 August 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated to August 2010. |

| 30 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

A restricted search in September 2019 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. The review will be re‐assessed for updating in two years. If appropriate, we will update the review before this date if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Acknowledgements

The researchers in the original review published in 2006 gratefully acknowledged the financial support provided by Janssen‐Cilag. Marie Curie Care funded both the 2010 and 2015 update of this review.

We acknowledge Claire Miles, Susie Wilkinson, Robyn Drake and Margaret Goodman, who were authors of earlier versions of this review and George Dowswell who assisted in the early stages of the updating of this review. We also acknowledge the support of Jessica Thomas, Caroline Struthers, Anna Hobson and Joanne Abbott of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS) or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies for 2014 update

Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care

| Database | Date searched | Number of results |

| CENTRAL Issue 8 of 12, 2014 (The Cochrane Library) (searched 2010 to 2014) |

10 September 2014 | 47 |

| MEDLINE and MEDLINE in Process (OVID) August 2010 to 9 September 2014 | 10 September 2014 | 147 |

| EMBASE (OVID) August 2010 to 9 September 2014 | 10 September 2014 | 429 |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) August 2010 to September 2014 | 16 September 2014 | 40 |

| Web of Science (SCI & CPCI‐S) 2010 to September 2014 | 16 September 2014 | 263 |

| Total | 926 | |

| After de‐duplication | 717 | |

CENTRAL

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Constipation] this term only

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Defecation] this term only

#3 MeSH descriptor: [Fecal Incontinence] this term only

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Feces] this term only

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Diarrhea] this term only

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Irritable Bowel Syndrome] this term only

#7 (constipat* or (hard near/3 stool*) or (bowel near/3 symptom*) or (impact* near/3 stool*) or (impact* near/3 feces) or (impact* near/3 faeces) or (fecal* near/3 incontin*) or (faecal* near/3 incontin*) or (fecal* near/3 impact*) or (faecal* near/3 impact*) or (loose near/3 stool*) or diarrh* or feces or faeces):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#8 (defecat* or (bowel* near/3 function*) or (bowel* near/3 habit*) or (bowel* near/3 symptom*) or (evacuat* near/3 f?eces) or (evacuat* near/3 bowel*) or (bowel* near/3 symptom*) or (bowel near/3 movement*) or (intestin* near/3 motility) or (colon near/3 transit*) or (void* near/3 bowel*) or (strain* near/3 bowel*) or (irritable bowel syndrome)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#9 MeSH descriptor: [Fecal Impaction] this term only

#10 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9

#11 (cathartic* or laxative* or purgative* or stimulant or osmotic or supposit* or "faecal softener*" or bulk‐forming or enema*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#12 MeSH descriptor: [Cathartics] explode all trees

#13 MeSH descriptor: [Laxatives] explode all trees

#14 (5‐HT4 agonist or 5‐hydroxytryptamine receptor subtype 4 agonist or actilax or actonorm* or aka hemp seed pill or aloe* or aludrox* or anthraquinone* or apo‐lactulose or (arachis near/2 oil) or aloin phenolphthalein or bethanechol or bifidobacterium supplement* or bisacodyl* or (bowel near/2 cleaning near/2 solution*) or bran or trifyba or (dietary near/2 (fibre or fiber)) or "bowl cleansing" or (bulk near/2 forming) or buckthrin):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#15 (calcium polycarbophil or calsalettes* or califig* or capsuvac* or carbalax or carbellon* or cascara or castranol or casanthranol or cellulose or celevac* or (chloride near/2 clinical near/2 activators) or cephulac or cholac or cilac or citroma or constilac or chronulac or citramag* or citrafleet or codalax or codanthramer* or co‐danthrusate* or codanthrusate or cologel* or colyte or creon* or colocynth or danlax or dantron* or danthron* or dioctyl* or (dioctyl near/2 sodium near/2 sulphosuccinate) or didaccharide or docusate or dulcolax* or duphalac* or dulcolax or docusol* or docisate sodium):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#16 (enulose or (epsom near/2 salt*) or ex‐lax* or exlax or (f?ecal near/2 softener*) or fam‐lax‐senna* or emollients or fibrelief or fleet enema or fleet phospho‐soda or (fleet* near/2 fletcher*) or (fletcher* near/2 enemette*) or fortans or forlax or frangula or (fruit near/2 juice*) or fybogel* or frangula or generiac or glycerol or glycerin or glucitol or goitely or grangula* or golytely or ground‐nut or ground nut or heptalac or idrolax* or indoles or ispaghula or ispaghula or isogel* or ispagel* or (jackson* near/2 herb*) or jalap or (juno near/2 junipah near/2 salts*) or kiwi or (klean near/2 prep*) or konsyl* or kristalose or lactuga* or lactitol or lactulose* or lactobacillus or laxoberal* or laxido or (liquid near/2 paraffin) or Lubiprostone or linaclotide):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#17 (maalox* or macrogol* or magnesium hydroxide or (magnesium near/2 (salt* or compound* or hydroxide or sulphate* or citrate*)) or manevac or macrogol or magnesium sulphate or movicol* or (magnesium hydroxide) or manevac* or methylcellulose or (milk near/2 magnesia*) or mineral oil or (micolette near/2 micro‐enema*) or (micralax near/2 micro‐enema*) or miralax or moviprep or mucaine* or mucogel* or movicol or neostigmine or (nylax near/2 senna*) or normax* or normacol* or norgine* or norgalax* or nutrizym* or nutiteky or osmolax* or osmotic or osmoprep or operles*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#18 (pancrease* or pancrex* or pancreatin* or pear or peanut oil or phenols or phenolphthalein* or phosphate* or (phosphate near/2 enema*) or picolax* or PEG or (polyethylene near/2 glycol*) or PMF‐100 or poloxalkol or poloxamer or (potter* near/2 cleansing near/2 herb*) or prune* or Probiotic* or pricalopride or psyllium or pyridostigmine or regulose* or regulan* or (relaxit near/2 micro‐enema*) or receptors or roughage or rhubarb or rhuaka* or sanochemia or senna* or senokot* or senako* or serotonin agonists or ((sodium picosulfate or sodium) near/2 picosulfate) or sorbitol or sterculia* or suppositor* or (syrup near/3 fig*) or (sodium near/2 alginate) or (sodium near/2 acid near/2 phosphate) or (sodium near/2 (salts or citrate)) or stool softener* or sterculia or tegaserod or transipeg or trilyte or visicol or yun‐chang):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#19 #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18

#20 MeSH descriptor: [Palliative Care] this term only

#21 MeSH descriptor: [Terminal Care] this term only

#22 MeSH descriptor: [Terminally Ill] this term only

#23 MeSH descriptor: [Hospice Care] this term only

#24 (palliat* or terminal* or endstage or hospice* or (end near/3 life) or (care near/3 dying) or ((advanced or late or last or end or final) near/3 (stage* or phase*))):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#25 #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24

#26 #25 and #19 and #10 Publication Year from 2010 to 2014

MEDLINE & MEDLINE in Process

1. Constipation/

2. Defecation/

3. Fecal Incontinence/

4. Feces/

5. Diarrhea/

6. Irritable Bowel Syndrome/

7. (constipat* or (hard adj3 stool*) or (bowel adj3 symptom*) or (impact* adj3 stool*) or (impact* adj3 feces) or (impact* adj3 faeces) or (fecal* adj3 incontin*) or (faecal* adj3 incontin*) or (fecal* adj3 impact*) or (faecal* adj3 impact*) or (loose adj3 stool*) or diarrh* or feces or faeces).tw.

8. (defecat* or (bowel* adj3 function*) or (bowel* adj3 habit*) or (bowel* adj3 symptom*) or (evacuat* adj3 f#eces) or (evacuat* adj3 f#eces) or (evacuat* adj3 bowel*) or (bowel* adj3 symptom*) or (bowel adj3 movement*) or (intestin* adj3 motility) or (colon adj3 transit*) or (void* adj3 bowel*) or (strain* adj3 bowel*) or (irritable adj bowel adj syndrome)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

9. Fecal Impaction/

10. or/1‐9

11. (cathartic* or laxative* or purgative* or stimulant or osmotic or supposit* or "faecal softener*" or bulk‐forming or enema*).tw.

12. exp cathartics/ or exp laxatives/

13. (5‐HT4 agonist or 5‐hydroxytryptamine receptor subtype 4 agonist or actilax or actonorm* or aka hemp seed pill or aloe* or aludrox* or anthraquinone* or apo‐lactulose or (arachis adj2 oil) or aloin phenolphthalein or bethanechol or bifidobacterium supplement* or bisacodyl* or (bowel adj2 cleaning adj2 solution*) or bran or trifyba or (dietary adj2 (fibre or fiber)) or "bowl cleansing" or (bulk adj2 forming) or buckthrin).tw.

14. (calcium polycarbophil or calsalettes* or califig* or capsuvac* or carbalax or carbellon* or cascara or castranol or casanthranol or cellulose or celevac* or (chloride adj2 clinical adj2 activators) or cephulac or cholac or cilac or citroma or constilac or chronulac or citramag* or citrafleet or codalax or codanthramer* or co‐danthrusate* or codanthrusate or cologel* or colyte or creon* or colocynth or danlax or dantron* or danthron* or dioctyl* or (dioctyl adj2 sodium adj2 sulphosuccinate) or didaccharide or docusate or dulcolax* or duphalac* or dulcolax or docusol* or docisate sodium).tw.

15. (enulose or (epsom adj2 salt*) or ex‐lax* or exlax or (f#ecal adj2 softener*) or fam‐lax‐senna* or emollients or fibrelief or fleet enema or fleet phospho‐soda or (fleet* adj2 fletcher*) or (fletcher* adj2 enemette*) or fortans or forlax or frangula or (fruit adj2 juice*) or fybogel* or frangula or generiac or glycerol or glycerin or glucitol or goitely or grangula* or golytely or ground‐nut or ground nut or heptalac or idrolax* or indoles or ispaghula or ispaghula or isogel* or ispagel* or (jackson* adj2 herb*) or jalap or (juno adj2 junipah adj2 salts*) or kiwi or (klean adj2 prep*) or konsyl* or kristalose or lactuga* or lactitol or lactulose* or lactobacillus or laxoberal* or laxido or (liquid adj2 paraffin) or Lubiprostone or linaclotide).tw.

16. (maalox* or macrogol* or magnesium hydroxide or (magnesium adj2 (salt* or compound* or hydroxide or sulphate* or citrate*)) or manevac or macrogol or magnesium sulphate or movicol* or (magnesium adj hydroxide) or manevac* or methylcellulose or (milk adj2 magnesia*) or mineral oil or (micolette adj2 micro‐enema*) or (micralax adj2 micro‐enema*) or miralax or moviprep or mucaine* or mucogel* or movicol or neostigmine or (nylax adj2 senna*) or normax* or normacol* or norgine* or norgalax* or nutrizym* or nutiteky or osmolax* or osmotic or osmoprep or operles*).tw.

17. (pancrease* or pancrex* or pancreatin* or pear or peanut oil or phenols or phenolphthalein* or phosphate* or (phosphate adj2 enema*) or picolax* or PEG or (polyethylene adj2 glycol*) or PMF‐100 or poloxalkol or poloxamer or (potter* adj2 cleansing adj2 herb*) or prune* or Probiotic* or pricalopride or psyllium or pyridostigmine or regulose* or regulan* or (relaxit adj2 micro‐enema*) or receptors or roughage or rhubarb or rhuaka* or sanochemia or senna* or senokot* or senako* or serotonin agonists or ((sodium picosulfate or sodium) adj2 picosulfate) or sorbitol or sterculia* or suppositor* or (syrup adj3 fig*) or (sodium adj2 alginate) or (sodium adj2 acid adj2 phosphate) or (sodium adj2 (salts or citrate)) or stool softener* or sterculia or tegaserod or transipeg or trilyte or visicol or yun‐chang).tw.

18. or/11‐17

19. Palliative Care/

20. Terminal Care/

21. Terminally Ill/

22. Hospice Care/

23. (palliat* or terminal* or endstage or hospice* or (end adj3 life) or (care adj3 dying) or ((advanced or late or last or end or final) adj3 (stage* or phase*))).tw.

24. or/19‐23

25. 10 and 18 and 24

EMBASE

1. Constipation/

2. Defecation/

3. Feces Incontinence/

4. Feces/

5. Diarrhea/

6. Irritable Colon/

7. (constipat* or (hard adj3 stool*) or (bowel adj3 symptom*) or (impact* adj3 stool*) or (impact* adj3 feces) or (impact* adj3 faeces) or (fecal* adj3 incontin*) or (faecal* adj3 incontin*) or (fecal* adj3 impact*) or (faecal* adj3 impact*) or (loose adj3 stool*) or diarrh* or feces or faeces).tw.

8. (defecat* or (bowel* adj3 function*) or (bowel* adj3 habit*) or (bowel* adj3 symptom*) or (evacuat* adj3 f#eces) or (evacuat* adj3 f#eces) or (evacuat* adj3 bowel*) or (bowel* adj3 symptom*) or (bowel adj3 movement*) or (intestin* adj3 motility) or (colon adj3 transit*) or (void* adj3 bowel*) or (strain* adj3 bowel*) or (irritable adj bowel adj syndrome)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

9. Feces Impaction/

10. or/1‐9

11. (cathartic* or laxative* or purgative* or stimulant or osmotic or supposit* or "faecal softener*" or bulk‐forming or enema*).tw.

12. exp laxative/

13. (5‐HT4 agonist or 5‐hydroxytryptamine receptor subtype 4 agonist or actilax or actonorm* or aka hemp seed pill or aloe* or aludrox* or anthraquinone* or apo‐lactulose or (arachis adj2 oil) or aloin phenolphthalein or bethanechol or bifidobacterium supplement* or bisacodyl* or (bowel adj2 cleaning adj2 solution*) or bran or trifyba or (dietary adj2 (fibre or fiber)) or "bowl cleansing" or (bulk adj2 forming) or buckthrin).tw.

14. (calcium polycarbophil or calsalettes* or califig* or capsuvac* or carbalax or carbellon* or cascara or castranol or casanthranol or cellulose or celevac* or (chloride adj2 clinical adj2 activators) or cephulac or cholac or cilac or citroma or constilac or chronulac or citramag* or citrafleet or codalax or codanthramer* or co‐danthrusate* or codanthrusate or cologel* or colyte or creon* or colocynth or danlax or dantron* or danthron* or dioctyl* or (dioctyl adj2 sodium adj2 sulphosuccinate) or didaccharide or docusate or dulcolax* or duphalac* or dulcolax or docusol* or docisate sodium).tw.

15. (enulose or (epsom adj2 salt*) or ex‐lax* or exlax or (f#ecal adj2 softener*) or fam‐lax‐senna* or emollients or fibrelief or fleet enema or fleet phospho‐soda or (fleet* adj2 fletcher*) or (fletcher* adj2 enemette*) or fortans or forlax or frangula or (fruit adj2 juice*) or fybogel* or frangula or generiac or glycerol or glycerin or glucitol or goitely or grangula* or golytely or ground‐nut or ground nut or heptalac or idrolax* or indoles or ispaghula or ispaghula or isogel* or ispagel* or (jackson* adj2 herb*) or jalap or (juno adj2 junipah adj2 salts*) or kiwi or (klean adj2 prep*) or konsyl* or kristalose or lactuga* or lactitol or lactulose* or lactobacillus or laxoberal* or laxido or (liquid adj2 paraffin) or Lubiprostone or linaclotide).tw.

16. (maalox* or macrogol* or magnesium hydroxide or (magnesium adj2 (salt* or compound* or hydroxide or sulphate* or citrate*)) or manevac or macrogol or magnesium sulphate or movicol* or (magnesium adj hydroxide) or manevac* or methylcellulose or (milk adj2 magnesia*) or mineral oil or (micolette adj2 micro‐enema*) or (micralax adj2 micro‐enema*) or miralax or moviprep or mucaine* or mucogel* or movicol or neostigmine or (nylax adj2 senna*) or normax* or normacol* or norgine* or norgalax* or nutrizym* or nutiteky or osmolax* or osmotic or osmoprep or operles*).tw.

17. (pancrease* or pancrex* or pancreatin* or pear or peanut oil or phenols or phenolphthalein* or phosphate* or (phosphate adj2 enema*) or picolax* or PEG or (polyethylene adj2 glycol*) or PMF‐100 or poloxalkol or poloxamer or (potter* adj2 cleansing adj2 herb*) or prune* or Probiotic* or pricalopride or psyllium or pyridostigmine or regulose* or regulan* or (relaxit adj2 micro‐enema*) or receptors or roughage or rhubarb or rhuaka* or sanochemia or senna* or senokot* or senako* or serotonin agonists or ((sodium picosulfate or sodium) adj2 picosulfate) or sorbitol or sterculia* or suppositor* or (syrup adj3 fig*) or (sodium adj2 alginate) or (sodium adj2 acid adj2 phosphate) or (sodium adj2 (salts or citrate)) or stool softener* or sterculia or tegaserod or transipeg or trilyte or visicol or yun‐chang).tw.

18. or/11‐17

19. Palliative Therapy/

20. Terminal Care/

21. Terminally Ill Patient/

22. Hospice Care/

23. (palliat* or terminal* or endstage or hospice* or (end adj3 life) or (care adj3 dying) or ((advanced or late or last or end or final) adj3 (stage* or phase*))).tw.

24. or/19‐23

25. 10 and 18 and 24

CINAHL

S27 S25 AND S26

S26 EM 20100801‐20140930

S25 (S10 AND S18 AND S24)

S24 S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23

S23 (palliat* or terminal* or endstage or hospice* or (end near/3 life)

or (care near/3 dying) or ((advanced or late or last or end or final)

near/3 (stage* or phase*)))

S22 (MH "Hospice Care")

S21 (MH "Terminally Ill Patients")

S20 (MH "Terminal Care")

S19 (MH "Palliative Care")

S18 S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17

S17 (pancrease* or pancrex* or pancreatin* or pear or peanut oil or

phenols or phenolphthalein* or phosphate* or (phosphate near/2 enema*)

or picolax* or PEG or (polyethylene near/2 glycol*) or PMF‐100 or

poloxalkol or poloxamer or (potter* near/2 cleansing near/2 herb*) or

prune* or Probiotic* or pricalopride or psyllium or pyridostigmine or

regulose* or regulan* or (relaxit near/2 micro‐enema*) or receptors or

roughage or rhubarb or rhuaka* or sanochemia or senna* or senokot* or

senako* or serotonin agonists or ((sodium picosulfate or sodium) near/2

picosulfate) or sorbitol or sterculia* or suppositor* or (syrup near/3

fig*) or (sodium near/2 alginate) or (sodium near/2 acid near/2

phosphate) or (sodium near/2 (salts or citrate)) or stool softener* or

sterculia or tegaserod or transipeg or trilyte or visicol or

yun‐chang)

S16 (maalox* or macrogol* or magnesium hydroxide or (magnesium near/2

(salt* or compound* or hydroxide or sulphate* or citrate*)) or manevac

or macrogol or magnesium sulphate or movicol* or (magnesium hydroxide)

or manevac* or methylcellulose or (milk near/2 magnesia*) or mineral oil

or (micolette near/2 micro‐enema*) or (micralax near/2 micro‐enema*) or

miralax or moviprep or mucaine* or mucogel* or movicol or neostigmine or

(nylax near/2 senna*) or normax* or normacol* or norgine* or norgalax*

or nutrizym* or nutiteky or osmolax* or osmotic or osmoprep or

operles*)

S15 (enulose or (epsom near/2 salt*) or ex‐lax* or exlax or (f?ecal

near/2 softener*) or fam‐lax‐senna* or emollients or fibrelief or fleet

enema or fleet phospho‐soda or (fleet* near/2 fletcher*) or (fletcher*

near/2 enemette*) or fortans or forlax or frangula or (fruit near/2

juice*) or fybogel* or frangula or generiac or glycerol or glycerin or

glucitol or goitely or grangula* or golytely or ground‐nut or ground nut

or heptalac or idrolax* or indoles or ispaghula or ispaghula or isogel*

or ispagel* or (jackson* near/2 herb*) or jalap or (juno near/2 junipah

near/2 salts*) or kiwi or (klean near/2 prep*) or konsyl* or kristalose

or lactuga* or lactitol or lactulose* or lactobacillus or laxoberal* or

laxido or (liquid near/2 paraffin) or Lubiprostone or linaclotide)

S14 (calcium polycarbophil or calsalettes* or califig* or capsuvac* or

carbalax or carbellon* or cascara or castranol or casanthranol or

cellulose or celevac* or (chloride near/2 clinical near/2 activators) or

cephulac or cholac or cilac or citroma or constilac or chronulac or

citramag* or citrafleet or codalax or codanthramer* or co‐danthrusate*

or codanthrusate or cologel* or colyte or creon* or colocynth or danlax

or dantron* or danthron* or dioctyl* or (dioctyl near/2 sodium near/2

sulphosuccinate) or didaccharide or docusate or dulcolax* or duphalac*

or dulcolax or docusol* or docisate sodium)

S13 (5‐HT4 agonist or 5‐hydroxytryptamine receptor subtype 4 agonist or

actilax or actonorm* or aka hemp seed pill or aloe* or aludrox* or

anthraquinone* or apo‐lactulose or (arachis near/2 oil) or aloin

phenolphthalein or bethanechol or bifidobacterium supplement* or

bisacodyl* or (bowel near/2 cleaning near/2 solution*) or bran or

trifyba or (dietary near/2 (fibre or fiber)) or "bowl cleansing" or

(bulk near/2 forming) or buckthrin)

S12 (MH "Cathartics")

S11 (cathartic* or laxative* or purgative* or stimulant or osmotic or

supposit* or "faecal softener*" or bulk‐forming or enema*)

S10 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9

S9 (MH "Feces, Impacted")

S8 (defecat* or (bowel* near/3 function*) or (bowel* near/3 habit*) or

(bowel* near/3 symptom*) or (evacuat* near/3 f?eces) or (evacuat* near/3

bowel*) or (bowel* near/3 symptom*) or (bowel near/3 movement*) or

(intestin* near/3 motility) or (colon near/3 transit*) or (void* near/3

bowel*) or (strain* near/3 bowel*) or (irritable bowel syndrome))

S7 (constipat* or (hard near/3 stool*) or (bowel near/3 symptom*) or

(impact* near/3 stool*) or (impact* near/3 feces) or (impact* near/3

faeces) or (fecal* near/3 incontin*) or (faecal* near/3 incontin*) or

(fecal* near/3 impact*) or (faecal* near/3 impact*) or (loose near/3

stool*) or diarrh* or feces or faeces)

S6 (MH "Irritable Bowel Syndrome")

S5 (MH "Diarrhea")

S4 (MH "Feces")

S3 (MH "Fecal Incontinence")

S2 (MH "Defecation")

S1 (MH "Constipation")

Web of Science (SCI & CPCI‐S)

# 12

#11 AND #10 AND #3

Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S, Timespan=2010‐2014

# 11

TOPIC: ((palliat* or terminal* or endstage or hospice* or (end near/3 life) or (care near/3 dying) or ((advanced or late or last or end or final) near/3 (stage* or phase*))))

Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S, Timespan=2010‐2014

# 10

#9 OR #8 OR #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4

Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S, Timespan=2010‐2014

# 9

TOPIC: ((pancrease* or pancrex* or pancreatin* or pear or peanut oil or phenols or phenolphthalein* or phosphate* or (phosphate near/2 enema*) or picolax* or PEG or (polyethylene near/2 glycol*) or PMF‐100 or poloxalkol or poloxamer or (potter* near/2 cleansing near/2 herb*) or prune* or Probiotic* or pricalopride or psyllium or pyridostigmine or regulose* or regulan* or (relaxit near/2 micro‐enema*) or receptors or roughage or rhubarb or rhuaka* or sanochemia or senna* or senokot* or senako* or serotonin agonists or (("sodium picosulfate" or sodium) near/2 picosulfate) or sorbitol or sterculia* or suppositor* or (syrup near/3 fig*) or (sodium near/2 alginate) or (sodium near/2 acid near/2 phosphate) or (sodium near/2 (salts or citrate)) or stool softener* or sterculia or tegaserod or transipeg or trilyte or visicol or yun‐chang))

Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S, Timespan=2010‐2014

# 8