Abstract

Matrix Gla protein (MGP) is an important regulatory protein for inhibition of calcification in the vessel wall and cartilage. The MGP gene polymorphisms are suspected to increase the risk of extracellular calcification through altering the related gene expression and serum MGP levels. The goal of this study was to examine the correlation between rs4236 (Thr83-Ala), rs12304 (Glu60-X) and rs1800802 (T138-C) polymorphisms of the MGP gene and coronary artery calcification. Serum MGP levels of 168 subjects who had undergone coronary angiography were analyzed along with genotyping of MGP gene polymorphisms. The results indicated that serum MGP levels were significantly associated with rs4236 and rs1800802 polymorphisms of the MGP gene with the occurrence of coronary artery diseases (CAD). Allelic distributions of MGP gene polymorphisms and serum MGP levels, respectively, were not significantly interconnected with the presence of CAD. Our results revealed that serum MGP levels of CAD patients show association with rs4236 and rs1800802 polymorphisms, but serum MGP levels alone do not directly reflect the risk of CAD. The role of MGP genetic variants on formation and progression of arterial calcification should be regarded in cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Coronary artery disease (CAD), Genetic polymorphism, Matrix Gla protein (MGP)

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have been the main cause of death worldwide in the past decade [1]. Efforts to overcome these diseases have gained crucial importance along with the increase in aging population. Screening of traditional risk factors could not provide sufficient information for CVD prediction. Approximately 25.0% of patients with CVD comprise asymptomatic individuals suffering from non fatal myocardial infarction or sudden death [2]. Therefore, in order to elucidate the causes of CVD, which lead to predisposition for this disease, new risk factors assessments have to be identified.

Arterial calcification affects the endothelial layer and the media of the vessel wall. Particularly, atherosclerotic vascular calcification is prevalent in the aging population, however atherosclerotic lesions can occur in earlier ages, even during fetal life, related with parental smoking [3]. Arterial calcification was found to progress with the differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into osteoblast- and chondrocyte-like cells [4]. For this reason, the role of various bone related genes in atherosclerotic processes were investigated to clarify underlying mechanisms [5, 6, 7]. Matrix Gla protein (MGP), a vitamin K-dependent matrix protein, participate in regulatory mechanisms of vascular calcification. It is an 84-amino acid protein, mainly expressed in bone matrix, cartilage and VSMCs.

Matrix Gla protein contains nine glutamate residues and five of them can be γ-carboxylated by vitamin K-dependent reaction. Gla residues have high affinity to calcium phosphate (hydroxyapatite) compound. Knockout mouse model experiments have demonstrated that MGP-deficient mice exhibited abnormal and severe arterial and cartilage calcification within a few weeks after birth [6]. Moreover, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of human MGP genes lead to either reduced protein expression or loss of function [8,9].

Previously, we investigated the associations of MGP SNPs with cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease [10]. We demonstrated that rs4236 and rs12304 SNPs of the MGP gene are significantly associated with CKD. Nonetheless, we could not find any correlation between variation of the MGP gene and serum MGP levels. In our present study, we assessed the relation between rs4236 (Thr83-Ala), rs12304 (Glu60-X) and rs1800802 (T138-C) SNPs of the MGP gene and coronary artery calcification. Furthermore, we analyzed serum MGP levels to evaluate their correlation with studied MGP gene variants.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Clinical Assessment. The study was conducted with 168 Caucasian participants recruited between February 2011 and November 2012 from the Cardiology Department of İstanbul Dr. Siyami Ersek Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Training and Research Hospital, İstanbul, Turkey. Patients suspected of having CAD with health complaints such as angina, atypical chest pain and chest distress, were enrolled in the study. After general medical inquiry, routine blood and urine assays, patients admitted to the Department of Cardiology to determine the presence of concomitant CAD. Coronary angiography was performed in all subjects through the femoral artery by the Judkins technique to determine the presence of arterial calcification. One hundred and twelve of subjects were considered as CAD patients, who had at least one vessel with >50.0% narrowing of the luminal diameter. The CAD group was also divided into three sub-groups as single-vessel disease (n = 62), two-vessel disease (n = 30) and three-vessel disease (n = 20), according to the number of main vessels with significant stenosis. Subjects who had normal coronary arteries, without cardiovascular disease, were enrolled as a control group (n = 56). Informed consent was provided by all volunteers who participated in the study. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of Marmara University and Turkish Ministry of Health, Central Ethics Committee (ID: 09.2011.0020, 2011). The patients with malignancies were excluded.

Demographic and clinical data, including underlying diseases such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, alcohol consumption and family history were collected from medical records. Biochemical data related with CAD, such as serum glucose, triglyceride, low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, total cholesterol and creatinine, were assayed using routine clinical methods. Table 1 represents demographic and biochemical profiles of participants.

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the coronary artery disease patients and controls. (Values are presented as mean ± SD and percent.)

| Parameters | CAD Patients (n = 112) | Controls (n = 56) | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (F; M) | F: 22; M: 90 | F: 30; M: 26 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 62.63 ± 9.16 | 56.40 ± 9.40 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 76 (67.9%) | 34 (60.7%) | 0.384 |

| DMT2 | 52 (46.2%) | 20 (35.7%) | 0.244 |

| Current smoker | 66 (58.9%) | 29 (51.8%) | 0.406 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 114.99 ± 43.28 | 104.67 ± 32.47 | 0.463 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44.61 ± 13.49 | 41.33 ± 12.14 | 0.228 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.81 ± 52.96 | 176.42 ± 39.45 | 0.310 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 176.22 ± 106.12 | 149.26 ± 68.27 | 0.234 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 122.21 ± 47.81 | 109.79 ± 24.89 | 0.215 |

| eGFR (mL/min./1.73m3) | 90.37 ± 19.83 | 84.83 ± 22.81 | 0.051 |

| sMGP (μg/L) | 0.82 ± 0.37 | 0.87 ± 0.42 | 0.426 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; DMT2: Diabetes mellitus type II; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; sMGP: serum MGP.

Adjusted for age and gender status.

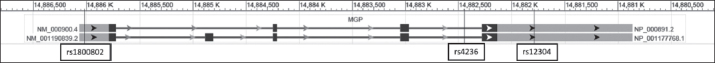

Genotyping of MGP SNPs. Peripheral blood samples from participants were collected and then genomic DNA was extracted by Roche DNA isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The geno-typing of rs1800802 (T138-C) in the promoter region, rs4236 (Thr83-Ala) and rs12304 (Glu60-X) in exon 4 of the MGP gene, was carried out using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), (CSL Gradient Thermal Cycler; Cleaver Scientific Ltd., Rugby, Warwickshire, UK). The location of the studied SNPs on a schematic representation of the MGP gene structure are shown in Figure 1. Genotyping of rs1800802 and rs4236 SNPs was performed by using PCR with subsequent restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis as previously reported by Garbuzova et al. [11]. Genotyping of rs12304 polymorphism was carried out as described previously [10].

Figure 1.

The structure of the human MGP gene showing the location of the rs4236, rs12304 and rs1800802 polymorphisms.

Serum MGP Levels. Serum samples of participants were separated from whole blood and kept at –20 °C until they were analyzed. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) provided by Sunred Biological Technology (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) was used to measure concentrations of serum MGP.

Statistical Analyses. The statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®) software (version 20) (https://ibm.com/ SPSS-Statistics/Software). All results expressed as means ± SD and p value less than 0.05 were defined to be statistically significant. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) testing was executed to compare the monitored and expected genotype frequencies of subjects using the χ2 test. Descriptive statistics and multivariate analyses were performed to estimate the relationships between clinical profiles and MGP alleles. The results were adjusted for the cofounders age and gender. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds ratio (OR) of the genotype for the occurrence of CAD. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) block structures of MGP gene SNPs, HWE test and calculation of haplotype frequencies and estimated associations between haplotypes and CAD risk were performed by Haploview (version 4.2) (https://www.broad institute.org/haploview/haploview) [12].

Results

Clinical Characteristics of the Participants. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of 168 subjects and their biochemical parameters indicated as risk factors for CAD. There were no significant differences between glucose, triglyceride, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol levels, estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) of CAD patients and controls (p >0.05). Furthermore, CAD patients were isolated into subgroups as single-vessel disease (n = 62; 55.3%), two-vessel disease (n = 30; 26.8%) and three-vessel disease (n = 20; 17.9%). Serum MGP concentrations were not statistically different between CAD patients and controls (p >0.05).

Genotype Distribution of MGP SNPs and Their Associations with CAD Risk and Biochemical Profiles. Genotype frequencies and allele distributions of MGP SNPs rs1800802, rs4236 and rs12304, which were in accordance with HWE expectations, are presented in Table 2. The genotype distributions of rs1800802, rs4236 and rs12304 SNPs were not statistically different between CAD patients and healthy controls (p = 0.701, 0.267, 0.936, respectively). The relation between allele distribution and CAD risk was evaluated by multinomial logistic regression analysis and the results are shown in Table 3. The correlation between rs1800802, rs4236 and rs12304 alleles and CAD risk was not statistically significant (p = 0.822, 0.121 and 0.936, respectively). Moreover, no association was found between the presence of single-, two-, and three-vessel disease and MGP alleles.

Table 2.

Genotype and allele distributions of matrix Gla protein gene rs1800802, rs4236, and rs12304 polymorphisms.

| Genotype/Allele | CAD Patients (n = 112) | Controls (n = 56) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs1800802 | |||

| Genotype: TT | 42 (37.5%) | 22 (39.3%) | |

| TC | 55 (49.1%) | 29 (51.8%) | 0.701 |

| CC | 15 (13.4%) | 5 (8.9%) | |

| Allele: T | 139 (62.0%) | 73 (65.2%) | |

| C | 85 (38.0%) | 39 (34.8%) | 0.822 |

| rs4236 | |||

| Genotype: Thr/Thr | 37 (33.0%) | 12 (21.4%) | 0.267 |

| Thr/Ala | 57 (50.9%) | 35 (62.5%) | |

| Ala/Ala | 18 (16.1%) | 9 (16.1%) | |

| Allele: Thr | 131 (58.5%) | 59 (52.7%) | |

| Ala | 93 (41.5%) | 53 (47.3%) | 0.119 |

| rs12304 | |||

| Genotype: Glu/Glu | 89 (79.5%) | 44 (80.0%) | 0.936 |

| Glu/X | 23 (20.5%) | 11 (20.0%) | |

| X/X | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Allele: Glu | 201 (89.7%) | 99 (90.0%) | 0.936 |

| X | 23 (10.3%) | 11 (10.0%) |

CAD: coronary artery disease.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals for alleles of matrix Gla protein genotypes for coronary artery disease.

| Genotypes | CAD Patients (n = 112) | Single-Vessel Disease (n = 62) | Two-Vessel Disease (n = 30) | Three-Vessel Disease (n = 20) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Valuea | OR (95% CI) | p Valuea | OR (95% CI) | p Valuea | OR (95% CI) | p Valuea | |

| rs1800802: TT vs. | ||||||||

| TT+CC | 0.927 (0.480-1.792) | 0.822 | 0.736 (0.346-1.567) | 0.426 | 1.182 (0.481-2.905) | 0.716 | 1.264 (0.451-3.457) | 0.655 |

| rs4236: Thr/Thr vs. | ||||||||

| Thr/Ala+Ala/Ala | 1.809 (0.854-3.829) | 0.121 | 1.878 (0.821-4.294) | 0.135 | 1.833 (0.680-4.943) | 0.231 | 1.571 (0.498-4.962) | 0.441 |

| rs12304: Glu/Glu vs. | ||||||||

| Glu/X+X/X | 0.967 (0.433-2.162) | 0.936 | 0.857 (0.352-2.086) | 0.734 | 1.625 (0.469-5.631) | 0.444 | 0.750 (0.224-2.512) | 0.641 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

a Control group is the reference category.

The allele distributions of SNPs were further evaluated to view the association of MGP gene variants with clinical risk factors for CAD (Table 4). Particularly, polymorphism rs4236 had a correlation with serum HDL-cholesterol (p = 0.049).

Table 4.

The baseline distribution characteristics of MGP alleles and their correlation with serum MGP concentrations. (Values are presented as mean ± SD.)

| Parameters | rs1800802 | rs4236 | rs12304 | sMGP (μg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT+TT vs. CC | p Valuea | Thr/Thr/Ala+Thr Ala/vs. Ala | p Valuea | Glu/Glu/Glu X+X/vs. X | p Valuea | Correlation | |

| Gender (F; M) | F:22; M: 30; F: 42; M: 74 | 0.452 | F: 9; M: 43; F: 40; M: 76 | 0.024 | F: 39; M: 12; F: 94; M:22 | 0.500 | 0.043 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 106.81±38.62; 113.93±41.19 | 0.701 | 117.61±42.17; 108.47±39.26 | 0.394 | 112.15±37.40; 112.21±53.30 | 0.878 | 0.222 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44.69±16.78; 43.13±11.31 | 0.556 | 46.87±14.79; 41.72±11.76 | 0.049 | 44.29±8.53; 41.25±8.53 | 0.361 | 0.145 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 188.28±46.01; 185.56±51.14 | 0.344 | 195.10±45.91; 181.37±51.04 | 0.245 | 187.45±48.46; 185.10±53.94 | 0.939 | 0.085 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 170.81±83.15; 166.67±102.21 | 0.769 | 177.05±119.29; 162.67±81.21 | 0.528 | 162.09±84.13; 199.42±139.30 | 0.115 | 0.903 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 121.31±42.67; 117.13±42.46 | 0.544 | 125.54±51.81; 114.28±35.63 | 0.539 | 117.80±39.23; 121.63±56.52 | 0.653 | 0.588 |

| eGFR (mL/min./1.73m3) | 85.57±23.62; 86.75±20.99 | 0.835 | 88.80±22.01; 85.81±21.97 | 0.405 | 85.98±21.37; 88.70±24.28 | 0.377 | 0.015 |

sMGP, serum MGP; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

a Adjusted for age and gender status.

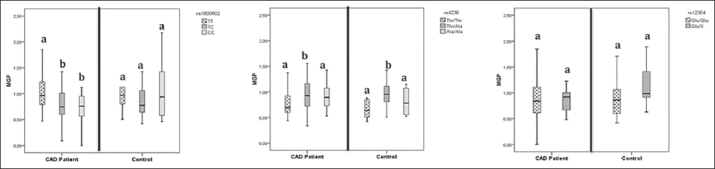

Associations Between MGP SNPs and Serum MGP Levels. The difference of serum MGP levels between CAD patients (0.82 ± 0.37 μg/L) and controls (0.87 ± 0.42 μg/L) were not statistically significant (p >0.05) (Table 1). Serum MGP levels demonstrated diversity related to the rs1800802 genotype distributions in CAD patients (p = 0.019). In addition, genotype distributions of rs4236 were associated with serum MGP levels, especially in the presence of CAD (CAD patients p = 0.012; controls p = 0.022). The histograms of serum MGP concentrations relative to MGP genotypes are shown in Figure 2. The eGFR profiles of subjects were correlated with serum MGP levels (p = 0.015) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Histograms of the serum MGP concentrations (μg/L) relative to MGP genotypes. The statistical significance between MGP concentrations were indicated by letters ‘a’ and ‘b.’

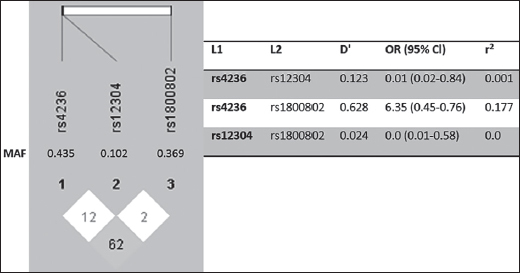

Haplotype Analysis and Associations Between Haplotypes and CAD Risk, and Serum MGP Levels. Linkage disequilibrium block structures of MGP SNPs were performed by Haploview [12]. Linkage disequilibrium was not observed in rs1800802, rs4236 and rs12304 and their D’ values were under 0.99. Figure 3 presents the LD block structures and their association with CAD risk. At the haplotype analysis, there was no correlation between three haplotypes and CAD risk. Furthermore, serum MGP concentrations showed no difference related to these haplotype distributions, according to multinomial logistic regression analysis.

Figure 3.

Linkage disequilibrium block structures of MGP gene polymorphisms was performed by Haploview (version 4.2) [12]. Numbers in squares (D’ values) indicate the pairwise correlation between polymorphisms. Color scheme from red to white represent higher to lower LD values.

Discussion

In our study, we reported that serum MGP levels were associated with rs4236 and rs1800802 SNPs of the MGP gene with the occurrence of CAD. As results from the studies investigating the relationship of MGP SNPs with the serum MGP levels in CAD patients were inconclusive, we believe our findings show evidence for this relationship. We did not observe association between serum MGP levels and MGP SNPs in CKD. Even though we demonstrated the effect of rs4236 and rs12304 SNPs on CKD progression, in the present study we did not find any significant correlation between these SNPs and CAD risk. On the other hand, our results demonstrated that investigated MGP variants might affect serum MGP levels in CAD patients.

The MGP is considered as one of the important regulatory proteins for inhibition of calcification in the vessel wall and cartilage. The MGP gene SNPs are propounded to alter MGP gene expression and serum MGP levels, therefore increasing the risk of extracellular calcification [13]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the relationship between MGP SNPs and cardiovascular diseases in relation with calcification [8,9,11,14]. Particularly, the role of rs1800802 and rs4236 SNPs in cardiovascular diseases has become prominent. The impact of the rs1800802 polymorphism on transcription in VSMCs was demonstrated in vitro, in addition to this result the differences in serum concentrations of MGP was correlated with genotypic variation [8].

The consequences of MGP genotype variants in CVD are conflicting in clinical researches. For instance, the role of MGP gene rs1800802 polymorphism on vascular calcifications was investigated by numerous studies, however, no significant association has been discovered in an abdominal aorta of autopsy cases [15], coronary arteries [14] or acute coronary syndrome and ischemic stroke [11]. Although certain studies demonstrated the association between the TT genotype of rs1800802 SNP and all-cause mortality and CVD risk in hemodialysis patients [16,17], our results did not show evidence linking the SNP with disease status in hemodialysis patients with CKD and CAD. On the other hand, the rs4236 polymorphism was found to be associated with myocardial infarction in low-risk individuals and assessed that this polymorphism contributed to coronary artery calcification [9]. Cassidy-Bushrow et al. [13] propounded that the rs4236 polymorphism has been shown to affect the progression of coronary artery calcification, however, it was not significantly associated with incident calcification. In that study, MGP genotypes were not involved in the quantity of coronary artery calcification; contrary to this, Crosier et al. [16] observed that rs1800802 or rs4236 SNPs were related to decreased quantity of calcification. A recently published meta-analysis, which evaluated the impact of MGP genetic variants in the process of vascular calcification, revealed that the rs1800801 (G7-A) polymorphism was associated with the risk of vascular calcification and atherosclerotic disease. However, rs800802 and rs4236 SNPs were not correlated with these diseases [18].

Matrix Gla protein comprises five γ-carboxyglutamate (Gla) amino acids and it is activated via γ-glutamate carboxylation and serine phosphorylation [4]. The carboxylated MGP is asserted as a potent inhibitor of vascular calcification [19,20]. The pathophysiological mechanisms for protection from vascular calcification are: 1) to have binding affinity to calcium-phosphate compound and prevent their aggregation within arterial wall; 2) to stimulate phagocytosis and apoptosis of the MGP-hydroxyapatite complex by regulating the macrophages; 3) to inhibit binding of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) to its receptor in order to prevent the differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into osteoblast- and chondrocyte-like cells [21]. The active form of MGP is both phosphorylated and carboxylated, whereas inactive forms are: uncarboxylated MGP (ucMGP), carboxylated but not phosphorylated MGP (dpcMGP), phosphorylated but uncarboxylated (pucMGP), and the fully inactive un-carboxylated, dephosphorylated MGP (dpucMGP). There are numerous studies that investigate the relationship between serum MGP and/or inactive forms of MGP levels, and vascular calcification in patients with CKD and CVD diseases, however, whether MGP SNPs have on effects serum MGP levels remain controversial [19,22,23].

We propounded that MGP levels might be modified in relation to the presence of polymorphic variants of the MGP gene in circulation of patients with CAD. Serum MGP levels were altered when associated with rs4236 and rs1800802 SNPs with the occurrence of CAD. The MGP levels increased when associated with the rs4236 variant, on the other hand, MGP levels were found to be low in association with the rs1800802 variant in the serum of CAD patients. However, the distributions of serum MGP levels were not statistically different between CAD patients and controls. Research conducted on incidence of altered MGP levels in vascular diseases are also contradictory.

In the meantime, the study of Wang et al. [24] is compatible to our results, hence, the rs4236 polymorphism found in association with higher MGP plasma levels and rs1800802 with lower levels. Even Farzaneh-Far et al. [8] propounded that the rs1800802 CC allele has increased the transcriptional activity of the MGP gene, direct or inverse relationship of the rs4236 or rs1800802 polymorphism with serum/plasma MGP concentrations could not be established by certain investigations [14,25]. Furthermore, the association between serum MGP levels and CAD has not been verified in clinical investigations. The possible explanation is the activation of MGP occurring with modifications including carboxylation and phosphorylation; under-carboxylated MGP shows high affinity for hydroxyapatite crystal, therefore, accumulates in atherosclerotic lesions [19,20,26].

We evaluated the two-allelic haplotype distributions in the studied SNPs and LD was not found to be significant between control and patients. Crosier et al. [16] reported that LD values of rs1800802, rs1800801 and rs4236 SNPs were highly significant, otherwise Najafi et al. [14] did not indicate haplotype distributions between rs1800802, rs1800801 and rs1800799 SNPs.

The limitation of this study is that serum MGP levels are inadequate to accurately reflect MGP tissue levels in atherosclerotic lesions. Although the investigation was carried out in a limited number of CAD patients, study groups were classified by the presence of arterial calcification after coronary diagnostic angiography, which was supposed to improve the accuracy of study findings.

Our results revealed that rs4236 and rs1800802 variants of the MGP gene were associated with serum MGP levels in patients with CAD. However, genotype distributions of three SNPs and serum MGP levels were not correlated with the presence of CAD. As it is well known, CVD are multifactorial disorders, therefore, development of arterial calcification is affected by several conditions including hypertension, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and aging. Consequently, MGP gene polymorphisms might not directly influence the formation of CAD. Further large-scale investigations will elucidate the contribution of genetic variants of the MGP gene on formation and progression of arterial calcification in CVD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding. This study was supported by the Marmara University Research Foundation under Grant (Project ID: SAG-A-130511-0124).

References

- 1.Erbel R, Budoff M. Improvement of cardiovascular risk prediction using coronary imaging: Subclinical atherosclerosis: The memory of lifetime risk factor exposure. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(10):1201–1213. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Castellanos A. Sudden cardiac death: Epidemiology, transient risk, and intervention assessment. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(12):1187–1197. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-12-199312150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milei J, Ottaviani G, Lavezzi AM, Grana DR, Stella I, Matturri L. Perinatal and infant early atherosclerotic coronary lesions. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostrom K. Insights into the mechanism of vascular calcification. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(2A):20E–22E. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01718-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Morony S, Tarpley J, Capparelli C. Osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12(9):1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyer E, Behringer RR. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386(6620):78–81. doi: 10.1038/386078a0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schafer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, Westenfeld R, Ket-teler M, Floege J. The serum protein α2-Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(3):357–366. doi: 10.1172/JCI17202. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farzaneh-Far A, Davies JD, Braam LA, Spronk HM, Proudfoot D, Chan SW. A polymorphism of the human matrix γ-carboxyglutamic acid protein promoter alters binding of an activating protein-1 complex and is associated with altered transcription and serum levels. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(35):32466–32473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104909200. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrmann SM, Whatling C, Brand E, Nicaud V, Gariepy J, Simon A. Polymorphisms of the human matrix gla protein (MGP) gene, vascular calcification, and myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(11):2386–2393. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2386. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karsli Ceppioglu S, Yurdun T, Canbakan M. Assessment of matrix Gla protein, Klotho gene polymorphisms, and oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2011;33(9):866–874. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.605534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbuzova VY, Gurianova VL, Stroy DA, Dosenko VE, Parkhomenko AN, Ataman AV. Association of matrix Gla protein gene allelic polymorphisms (G(-7)→A, T(-138)→C and Thr(83)→Ala) with acute coronary syndrome in the Ukrainian population. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2012;17(1):30–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Bielak LF, Levin AM, Sheedy PF. Turner ST, Boerwinkle E. Matrix gla protein gene polymorphism is associated with increased coronary artery calcification progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(3):645–651. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300491. 2nd. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Najafi M, Roustazadeh A, Amirfarhangi A, Kazemi B. Matrix Gla protein (MGP) promoter polymorphic variants and its serum level in stenosis of coronary artery. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41(3):1779–1786. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi N, Kitazawa R, Maeda S, Schurgers L, Kitazawa S. T-138C polymorphism of matrix gla protein promoter alters its expression but is not directly associated with atherosclerotic vascular calcification. Kobe J Med Sci. 2004;50(3-4):69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crosier MD, Booth SL, Peter I, Dawson-Hughes B, Price PA, O’Donnell CJ. Matrix Gla protein poly-morphisms are associated with coronary artery calcification in men. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2009;55(1):59–65. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.55.59. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brancaccio D, Biondi ML, Gallieni M, Turri O, Galassi A, Cecchini F. Matrix GLA protein gene polymorphisms: Clinical correlates and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25(6):548–552. doi: 10.1159/000088809. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheng K, Zhang P, Lin W, Cheng J, Li J, Chen J. Association of Matrix Gla protein gene (rs1800801, rs1800802, rs4236) polymorphism with vascular calcification and atherosclerotic disease: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8713–8724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09328-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schurgers LJ, Teunissen KJ, Knapen MH, Kwaijtaal M, van Diest R, Appels A. Novel con-formationspecific antibodies against matrix γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) protein: Undercarboxylated matrix Gla protein as marker for vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(8):1629–1633. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000173313.46222.43. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweatt A, Sane DC, Hutson SM, Wallin R. Matrix Gla protein (MGP) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 in aortic calcified lesions of aging rats. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(1):178–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roumeliotis S, Dounousi E, Eleftheriadis T, Liakopoulos V. Association of the inactive circulating matrix gla protein with vitamin K intake, calcification, mortality, and cardiovascular disease: A review. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):628–655. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schurgers LJ, Barreto DV, Barreto FC, Liabeuf S, Renard C, Magdeleyns EJ. The circulating inactive form of matrix gla protein is a surrogate marker for vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: A preliminary report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(4):568–575. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07081009. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett H, O’Keeffe M, Kavanagh E, Walsh M, O’Connor EM. Is matrix gla protein associated with vascular calcification? A systematic review. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):415–433. doi: 10.3390/nu10040415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Chen J, Zhang Y, Yu W, Zhang C, Gong L. Common genetic variants of MGP are associated with calcification on the arterial wall but not with calcification present in the atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6(3):271–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000003. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roumeliotis S, Roumeliotis A, Panagoutsos S, Giannakopoulou E, Papanas N, Manolopoulos VG. Matrix Gla protein T-138C polymorphism is associated with carotid intima media thickness and predicts mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(10):1527–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.06.012. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spronk HM, Soute BA, Schurgers LJ, Cleutjens JP, Thijssen HH, De Mey JG. Matrix Gla protein accumulates at the border of regions of calcification and normal tissue in the media of the arterial vessel wall. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289(2):485–490. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5996. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]