Abstract

Background

Sensory stimulation via acupuncture has been reported to alter activities of numerous neural systems by activating multiple efferent pathways. Acupuncture, one of the main physical therapies in Traditional Chinese Medicine, has been widely used to treat patients with stroke for over hundreds of years. This is the first update of the Cochrane Review originally published in 2005.

Objectives

To assess whether acupuncture could reduce the proportion of people with death or dependency, while improving quality of life, after acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register (last searched on February 2, 2017), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Ovid (CENTRAL Ovid; 2017, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to February 2017), Embase Ovid (1974 to February 2017), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) EBSCO (1982 to February 2017), the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED; 1985 to February 2017), China Academic Journal Network Publishing Database (1998 to February 2017), and the VIP database (VIP Chinese Science Journal Evaluation Reports; 1989 to February 2017). We also identified relevant trials in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (last searched on Feburuary 20, 2017), the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (last searched on April 30, 2017), and Clinicaltrials.gov (last searched on April 30, 2017). In addition, we handsearched the reference lists of systematic reviews and relevant clinical trials.

Selection criteria

We sought randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of acupuncture started within 30 days from stroke onset compared with placebo or sham acupuncture or open control (no placebo) in people with acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, or both. Needling into the skin was required for acupuncture. Comparisons were made versus (1) all controls (open control or sham acupuncture), and (2) sham acupuncture controls.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors applied the inclusion criteria, assessed trial quality and risk of bias, and extracted data independently. We contacted study authors to ask for missing data. We assessed the quality of the evidence by using the GRADE approach. We defined the primary outcome as death or dependency at the end of follow‐up .

Main results

We included in this updated review 33 RCTs with 3946 participants. Twenty new trials with 2780 participants had been completed since the previous review. Outcome data were available for up to 22 trials (2865 participants) that compared acupuncture with any control (open control or sham acupuncture) but for only six trials (668 participants) that compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture control. We downgraded the evidence to low or very low quality because of risk of bias in included studies, inconsistency in the acupuncture intervention and outcome measures, and imprecision in effect estimates.

When compared with any control (11 trials with 1582 participants), findings of lower odds of death or dependency at the end of follow‐up and over the long term (≥ three months) in the acupuncture group were uncertain (odds ratio [OR] 0.61, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.46 to 0.79; very low‐quality evidence; and OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.85; eight trials with 1436 participants; very low‐quality evidence, respectively) and were not confirmed by trials comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.18; low‐quality evidence; and OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.12; low‐quality evidence, respectively).

In trials comparing acupuncture with any control, findings that acupuncture was associated with increases in the global neurological deficit score and in the motor function score were uncertain (standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.84, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.32; 12 trials with 1086 participants; very low‐quality evidence; and SMD 1.08, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.71; 11 trials with 895 participants; very low‐quality evidence). These findings were not confirmed in trials comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture (SMD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.57; low‐quality evidence; and SMD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.17; low‐quality evidence, respectively).

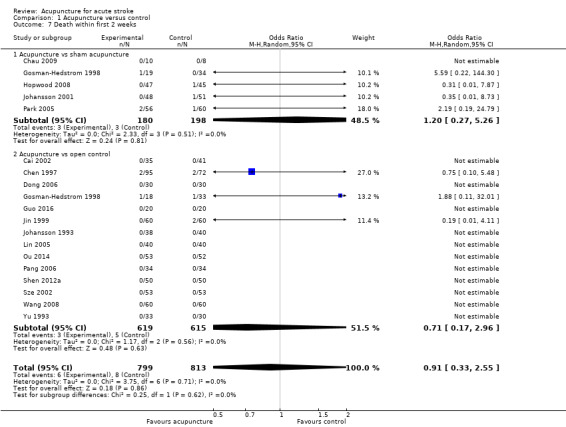

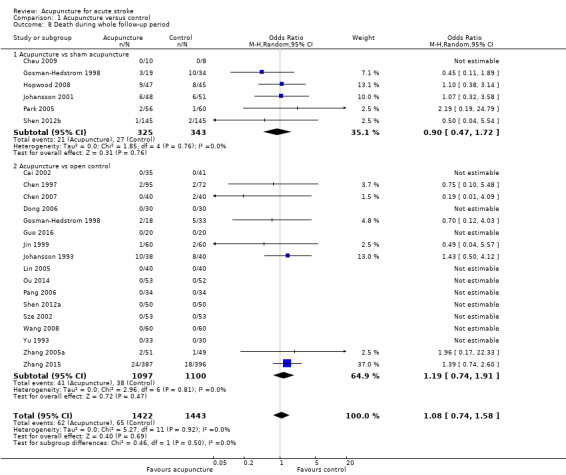

Trials comparing acupuncture with any control have reported little or no difference in death or institutional care at the end of follow‐up (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.12; five trials with 1120 participants; low‐quality evidence), death within the first two weeks (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.55; 18 trials with 1612 participants; low‐quality evidence), or death at the end of follow‐up (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.58; 22 trials with 2865 participants; low‐quality evidence).

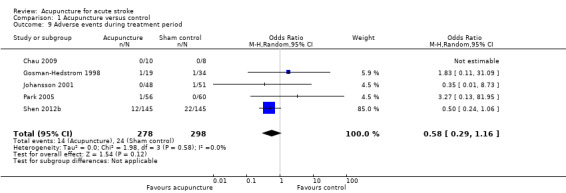

The incidence of adverse events (eg, pain, dizziness, faint) in the acupuncture arms of open and sham control trials was 6.2% (64/1037 participants), and 1.4% of these (14/1037 participants) discontinued acupuncture. When acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture, findings for adverse events were uncertain (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.16; five trials with 576 participants; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

This updated review indicates that apparently improved outcomes with acupuncture in acute stroke are confounded by the risk of bias related to use of open controls. Adverse events related to acupuncture were reported to be minor and usually did not result in stopping treatment. Future studies are needed to confirm or refute any effects of acupuncture in acute stroke. Trials should clearly report the method of randomization, concealment of allocation, and whether blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors was achieved, while paying close attention to the effects of acupuncture on long‐term functional outcomes.

Plain language summary

Acupuncture for acute stroke

Review question

To assess the effects and safety of acupuncture for rehabilitating people after stroke caused by blood clots or bleeding in the brain.

Background

Stroke is a devastating disease with high morbidity and mortality. Acupuncture, one of the main physical therapies in Traditional Chinese Medicine, has been widely used to treat stroke for over hundreds of years in China, but evidence of its effectiveness in stroke rehabilitation is inconsistent.

Study characteristics

We searched electronic databases and the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry up to February 2017, and two clinical trials platforms (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and Clinicaltrials.gov) up to April 2017. We included in this review 33 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with 3946 participants. Of these, results were available for up to 22 trials (2865 participants) that compared acupuncture with any control but for only six trials (668 participants) that compared acupuncture with a sham acupuncture procedure.

Key results

The effects of acupuncture in reducing death or dependency or improving neurological and movement scores at the end of follow‐up, as seen in trials comparing acupuncture with any control, were not seen in trials comparing acupuncture with the more reliable control of sham acupuncture. Adverse events such as pain, dizziness, and faint were reported in 6.2% (64/1037) of participants, and 1.4% (14) of these had to discontinue acupuncture.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was low or very low owing to risk of bias in the included studies and variation in the type and duration of acupuncture. Additional larger reliable research trials are required for enhanced confidence in the effects of acupuncture for acute stroke.

Summary of findings

Background

This review is the first update of a previously published review (Zhang 2005b).

Description of the condition

Stroke is a devastating disease with high morbidity and mortality. Stroke therapy is currently lacking in sufficient population‐wide treatments, thus it is estimated that the numbers of first‐ever stroke and stroke death will rise to 23 million and 7.8 million, respectively, by the year 2030 (Strong 2007). In China, stroke has become the leading cause of death, with a mortality rate of approximately 1.6 million among a population of 1.4 billion people. Furthermore, 2.5 million new strokes occur each year in China (Liu 2011), and the burden of stroke has increased over the past three decades (Wang 2017b). This reality drives researchers to test other adjunctive therapies including acupuncture in an attempt to reduce morbidity and mortality, especially given that approved and validated therapies for stroke, with the exception of aspirin and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, are limited.

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture is one of the main physical therapies in Traditional Chinese Medicine (Sze 2002); it has been widely used to treat patients with stroke in China for more than hundreds of years (Hu 1993). In recent years, acupuncture has attracted the attention of physicians and stroke survivors in Western countries (Hopwood 2008; Park 2005). However, evidence of its effectiveness in stroke rehabilitation is inconsistent.

How the intervention might work

Acupuncture may improve muscle movement (Zhang 2016), may exert various biochemical effects including up‐regulating expression of hippocampal lipoprotein receptor‐related protein (LRP1) as reported by Xue 2011 and down‐regulating expression of interleukin (IL)‐1β mRNA as described by Fang 2013, and may improve treatment response among those with neuroinflammatory disorders (Deng 2015). A previous study showed a time‐wise coincidence with the occurrence of endogenous opioids and endorphins with use of acupuncture, which activates multiple efferent pathways to alter activities of numerous neural systems (Han 1982).

Notably, acupuncturists who perform acupuncture action must receive training in standardized acupuncture procedures, and they must be qualified and experienced to ensure uniformity. In addition, sterile disposable stainless steel needles should be used to ensure safety (Chau 2009; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Zhang 2015). "De Chi," the needling sensation, is provoked at each point by manual stimulation (Chau 2009; Hopwood 2008; Park 2005). When electrical stimulation is used, the intensity of stimulation is increased until tingling, warmth (as reported by Hopwood 2008 and Hsieh 2007), or muscle contractions (as indicated by Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998) around acupoints can be sensed by the patient.

Why it is important to do this review

Acupuncture is well accepted by doctors and patients in China. Although numerous studies have been conducted within and outside of China to examine the efficacy of acupuncture in stroke, trial results are not consistent (Sze 2002a). Over the past 10 years, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) exploring the safety and efficacy of acupuncture have been published (Chau 2009; Hsieh 2007; Park 2005; Zhang 2015). The previous version of this review, which included 14 trials, showed no clear evidence of efficacy of acupuncture for acute stroke, but the evidence base was small and intention‐to‐treat analysis was rarely mentioned (Zhang 2005b). The aim of this updated review is to analyze systematically all relevant RCTs, including those published since 2003, when we last searched the literature.

Objectives

To assess whether acupuncture could reduce the proportion of people with death or dependency, while improving quality of life, after acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included truly unconfounded randomized clinical trials (without restrictions of blinding, publication status, or language) comparing acupuncture with placebo or sham acupuncture, or open control (no placebo), in people with acute stroke. We excluded quasi‐randomized trials (those that refer to allocation using the sequence of admission, alternate case record numbers, alternation, date of birth, or day of the week). We also excluded confounded trials in which the treatment or control group received another active therapy, for example, acupuncture versus other intervention, or acupuncture plus other intervention versus control.

Types of participants

People of any age or sex with any type of acute stroke (within 30 days of stroke onset) were eligible. Diagnosis of stroke was based on one of the following: (1) consistency with the World Health Organization definition, that is, "the focal neurological impairment occurs suddenly, lasts more than 24 hours or leads to death, and was presumed of vascular origin"; (2) purely clinical features; or (3) brain imaging alone (ie, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or computed tomography scanning [CT]). We excluded trials that were restricted to people with subdural hematoma or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Types of interventions

We included trials assessing acupuncture treatment in people with acute stroke within 30 days of onset, regardless of duration and times of treatment. We included trials using traditional acupuncture, which refers to insertion of needles in classical meridian points, or contemporary acupuncture, by which needles are inserted into trigger points or into non‐meridian points, irrespective of the method of stimulation (hand or electrical stimulation). The control group received placebo or sham acupuncture or no acupuncture treatment (open control). With open control, routine treatments such as drug therapy or rehabilitation or both would be the same as those given to the real/sham acupuncture group. However, real/sham acupuncture would not be given to participants in the open control group. We also included trials comparing acupuncture plus another treatment versus the other treatment alone, thereby assessing acupuncture. Placebo acupuncture indicates needling attaching to the surface of the skin. Sham acupuncture refers to (1) needling prick on the surface of the skin, by which needles are placed in an area that is close to but not at acupuncture points, and (2) electro‐stimulation of subliminal skin via electrodes attached to the skin.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was death or dependency at the end of follow‐up. Dependency is defined as a state of being dependent on others for activities of daily living (ADL), for example, a Barthel Index (BI) score ≤ 60, a modified Rankin Scale (MRS) grade of 3 to 6, or the trialists' own definition. We included in a secondary analysis death or dependency reported in trials that followed participants for at least three months.

Secondary outcomes

Death or required institutional care or extensive family support at the end of follow‐up. In developing countries, extensive family support can be the main form of care for patients with severe neurological deficit. We also performed a secondary analysis of institutional care or extensive family support for participants who were followed up for at least three months after stroke.

Changes in neurological deficit score at the end of the scheduled treatment period and at the end of follow‐up (≥ three months after stroke onset). Measures could focus on (1) specific impairment (eg, Motricity Index, or Motor Assessment Scale, used to assess only motor function), or (2) global neurological deficit (eg, Canadian Neurological Scale [CNS], National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS], European Stroke Scale [ESS], Scandinavian Stroke Scale [SSS], modified Edinburgh‐Scandinavian Stroke Scale (MESSS) used to assess neurological function, such as motor function, sensor function, etc.).

Death from all causes within the first two weeks of treatment and during the whole follow‐up period

Quality of life (QOL), if assessed by included trials during the whole follow‐up period

Adverse events (AEs) and severe AEs that may relate to acupuncture alone, including faintness, dizziness, pain, bleeding, high blood pressure, infection and heart tamponades, spinal cord injury, puncture of a lung, disrupted pacemaker function, and other effects presumed to be caused by acupuncture or electro‐stimulation

Search methods for identification of studies

See the Specialized Register section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials without language restrictions and translated relevant papers when necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Ovid (CENTRAL Ovid; 2017, Issure 2) in the Cochrane Library; Appendix 1), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to February 2017; Appendix 2), Embase Ovid (1974 to February 2017; Appendix 3), the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register (last searched by the Managing Editor on February 2, 2017), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) EBSCO (1982 to February 2017; Appendix 4), the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED; 1985 to February 2017; Appendix 5), the China Academic Journal Network Publishing Database (1998 to February 2017), and the VIP database (VIP Chinese Science Journal Evaluation Reports; 1989 to February 2017). We also identified relevant trials in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn/searchproj.aspx; last searched on February 20, 2017; Appendix 6), the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/; last searched on May 9, 2017; Appendix 7), and Clinicaltrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/; last searched on May 9, 2017; Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of published systematic reviews of acupuncture for stroke and identified trials as we searched for relevant articles. We attempted to contact study authors of the included trials to ask for additional data; the authors of only four trials ‐ Chen 1997,Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998,Hopwood 2008,Johansson 2001 ‐ provided additional data for the previous version of this review (Zhang 2005b). We pooled these unpublished data into meta‐analyses in this updated review. We are grateful to these trial authors.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MX, DL) independently screened all studies identified by searching electronic databases and relevant references. We included eligible studies that met predetermined inclusion criteria and resolved disagreements through discussion, or by consultation with a third review author if necessary (SZ).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MX, DL) independently extracted data on study methods and characteristics of participants, interventions, and outcomes onto a data extraction form. We obtained additional information from study authors whenever possible.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated risk of bias in included studies by establishing whether each trial met the following methodological domains according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Method of randomization.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and outcome assessors.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We graded the risk of bias for each domain as high, low, or unclear. We provided information from the trial and justification for our judgement in "Risk of bias" tables. Two review authors (MX, DL) independently assessed risk of bias for each trial and resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author (SZ).

Measures of treatment effect

We reported the results of dichotomous outcomes as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes, we used mean differences (MDs) (when outcomes were measured on the same scale) or standardized mean differences (SMDs) (when outcomes were measured on different scales), together with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

For studies with non‐standard design, we managed data according to recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors for additional information whenever possible. However, no study authors replied to our requests for missing data. Notably, we pooled published data and unpublished data from four included RCTs into the meta‐analyses (Chen 1997; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 2001).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We considered I2 > 50% as substantial heterogeneity. We performed all analyses using a random‐effects model.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting biases using funnel plots (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We tested differences between acupuncture and control groups (combined placebo/sham acupuncture and open control) through overall comparison. We separately compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture and open control. We performed all meta‐analyses using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). We used the fixed‐effect approach for outcomes without substantial heterogeneity and the random‐effects approach for those with substantial heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We preplanned the following subgroup analyses to investigate the effects of acupuncture.

Different stroke subtypes (ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke).

Different start times (within and after 10 days from stroke onset).

Different stroke severity, which was determined by NIHSS, SSS, MESSS, CNS, or ESS, or by trialists' own definition at baseline.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform the following sensitivity analyses by excluding trials:

with open control;

in which adequate concealment of allocation was unclear; and

in which outcome evaluations were not blinded.

"Summary of findings" tables

We used GRADEpro (GRADEproGDT) software to retrieve data from RevMan and produced "Summary of findings" tables (Table 1; Table 2), which included the following.

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Acupuncture compared with all control (sham and open) for patients with acute stroke.

| Acupuncture compared with all control for patients with acute stroke | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with acute stroke Settings: rehabilitation after acute stroke for inpatients Intervention: acupuncturea Comparison: all control (sham and open) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Acupuncture | |||||

| Death or dependency at end of follow‐up | Study population | OR 0.61 (0.46 to 0.79) | 1582 (11 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb,c | Dependency was defined as BI ≤ 60 (of a potential total of 100), BI ≤ 70 (of a potential total of 100), or BI ≤ 12 (of a potential total of 20). One trial used the trialists' own definition. | |

| 347 per 1000 | 245 per 1000 (196 to 296) | |||||

| Death or dependency at end of follow‐up (> 3 months) | Study population | OR 0.67 (0.53 to 0.85) | 1436 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb,d | Dependency was defined as BI ≤ 60 (of a potential total of 100), BI ≤ 70 (of a potential total of 100), or BI ≤ 12 (of a potential total of 20). One trial used the trialists' own definition. | |

| 325 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (203 to 291) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 444 per 1000 | 349 per 1000 (297 to 404) | |||||

| Death or institutional care at end of follow‐up | Study population | OR 0.78 (0.54 to 1.12) | 1120 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowe | ||

| 162 per 1000 | 131 per 1000 (94 to 178) | |||||

| Changes in global neurological deficit score at end of treatment period | Mean change in global neurological deficit score at end of treatment period in intervention groups was 0.84 standard deviations higher (0.36 to 1.32 higher). | 1086 (12 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowf,g | Global neurological function was measured via modified Edinburgh‐Scandinavian Stroke Scale in 9 trials, NIHSS in 2, and SSS in 1. | ||

| Motor function at end of acupuncture treatment period | Mean motor function at end of acupuncture treatment period in intervention groups was 1.08 standard deviations higher (0.45 to 1.71 higher). | 895 (11 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowf,h | Motor function was measured via Fugl‐Meyer Assessment in 7 trials, Motricity Index in 1, motor function score in 1, Rivermead Mobility Index in 1, and mobility index in 1. | ||

| Death within first 2 weeks | Study population | OR 0.91 (0.33 to 2.55) | 1612 (18 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowi | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (3 to 25) | |||||

| Death during whole follow‐up period | Study population | OR 1.08 (0.74 to 1.58) | 2865 (22 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowj | ||

| 45 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (34 to 69) | |||||

| Adverse events related to acupuncture | See comments. | See comments. | See comments. | (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowk | The incidence of adverse events directly related to acupuncture (such as pain, dizziness, faint) was approximately 6.17% (64/1037 participants) in the acupuncture group, and 1.35% (14/1037 participants) discontinued acupuncture. AEs related to sham acupuncture occurred in 8.0% (24/298) of participants. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AEs: adverse events; BI: Barthel Index; CI: confidence interval; NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; OR: odds ratio; RCTs: randomized controlled trials; SSS: Scandinavian Stroke Scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aOf the 33 included RCTs, the acupuncture treatment type and period were heterogeneous. The acupuncture treatment period ranged from one to three months. The acupoints varied across trials. The needling sensation could be provoked by manual stimulation or electrical stimulation.

bDowngraded one level for serious inconsistency: variation in the definition of dependency and acupuncture treatment type and duration.

cDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the 11 included trials, eight had risk of performance bias and seven had risk of detection bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

dDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the eight included trials, six had risk of performance bias and four had risk of detection bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

eDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the five included trials, four had risk of performance bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

fDowngraded two levels for very serious inconsistency: considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) and variation in acupuncture treatment type and duration.

gDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the 13 included trials, at least eight trials had risk of allocation bias, performance bias, or detection bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

hDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the 11 included trials, at least six had risk of allocation bias, performance bias, or detection bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

iDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the 18 included trials, at least 10 trials had risk of allocation bias, performance bias, or detection bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

jDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: Among the 22 included trials, at least 11 trials had risk of allocation bias, performance bias, or detection bias; the result was not consistent with the sensitivity analysis using only sham controls.

kDowngraded two levels for very serious inconsistency: variation between trials in reporting of adverse events and in acupuncture treatment type and duration.

Summary of findings 2. Acupuncture compared with sham control for patients with acute stroke.

| Acupuncture compared with sham control for patients with acute stroke | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with acute stroke Settings: rehabilitation after acute stroke for inpatients Intervention: acupuncture1 Comparison: sham control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Acupuncture | |||||

| Death or dependency at end of follow‐up | Study population | OR 0.71 (0.43 to 1.18) | 262 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 464 per 1000 | 384 per 1000 (264 to 404) | |||||

| Death or dependency at end of follow‐up (> 3 months) | Study population | OR 0.67 (0.40 to 1.12) | 244 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

| 476 per 1000 | 376 per 1000 (256 to 496) | |||||

| Death or institutional care at end of follow‐up | Study population | OR 0.47 (0.23 to 0.96) | 145 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5 | ||

| 456 per 1000 | 286 per 1000 (126 to 476) | |||||

| Changes in global neurological deficit score at end of treatment period | Mean change in global neurological deficit score at end of treatment period in intervention groups was 0.01 standard deviations higher (0.55 lower to 0.57 higher). | 53 (1 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |||

| Motor function at end of acupuncture treatment period | Mean motor function at end of acupuncture treatment period in intervention groups was 0.10 standard deviations lower (0.38 lower to 0.17 higher). | 202 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,7 | |||

| Death within first 2 weeks | Study population | OR 1.20 (0.27 to 5.26) | 378 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,8 | ||

| 15 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (0 to 45) | |||||

| Death during whole follow‐up period | Study population | OR 0.90 (0.47 to 1.72) | 668 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,9 | ||

| 79 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (59 to 99) | |||||

| Adverse events related to acupuncture | See comments. | See comments. | OR 0.58 (0.29 to 1.16) | 576 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,10 | The incidence of adverse events directly related to acupuncture (such as pain, dizziness, faint) was approximately 8.0% (24/298) in sham acupuncture patients. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCTs: randomized controlled trials. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aOf the 33 included RCTs, the acupuncture treatment type and period were heterogeneous. The treatment period for acupuncture ranged from one to three months. Acupoints varied across trials. The needling sensation could be provoked by manual stimulation or electrical stimulation.

bDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: small number of studies and wide confidence intervals.

cDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: Among the four included trials, two trials had risk of performance bias or attrition bias.

dDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: Among the three included trials, one trial had risk of performance bias.

eDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: Among the two included trials, one trial had risk of performance bias.

fDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: single study and very wide confidence intervals.

gDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: Among the three included trials, at least two trials had risk of performance bias or attrition bias.

hDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: Among the five included trials, at least two trials had risk of performance bias or attrition bias.

iDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: Among the six included trials, at least two trials had risk of performance bias or attrition bias.

jDowngraded one level for serious inconsistency: Reporting of adverse events varied between trials.

A list of all important outcomes.

A measure of the typical burden of these outcomes, such as illustrative risk.

Relative effects.

Numbers of participants and studies addressing each outcome.

A grade of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome.

Comments.

We judged the quality of the evidence as "high," "moderate," "low," or "very low." We used the specific evidence grading system developed by the GRADE Collaboration (GRADE Working Group 2004) to judge the quality of evidence according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

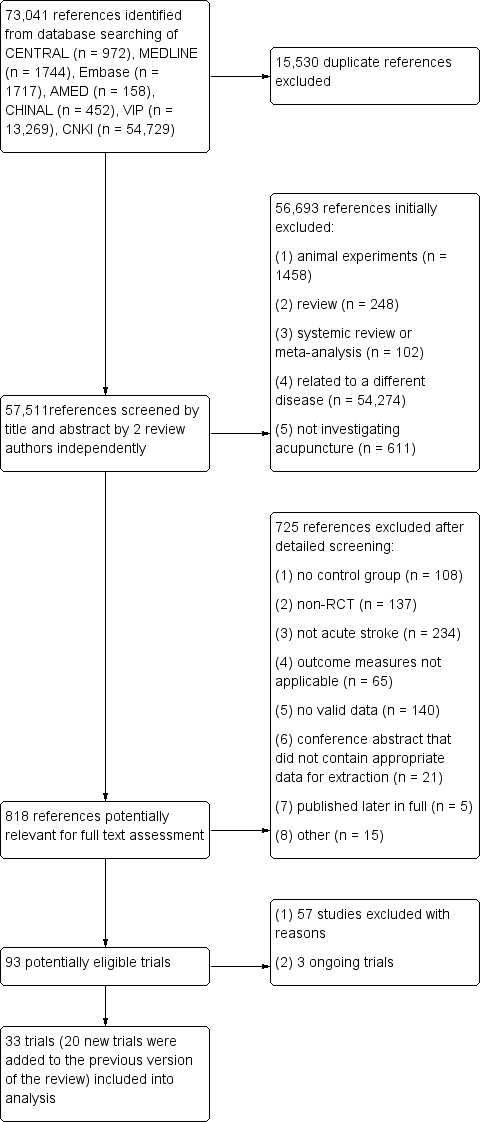

We identified 73,041 references from electronic databases and through handsearching. As shown in Figure 1, we excluded 15,530 duplicate references, 1458 references to animal experiments, 248 reviews, 102 systemic reviews or meta‐analyses, 54,274 references that related to a different disease, 611 references that did not investigate acupuncture, and 725 references because of no control group, non‐RCT, or non‐acute stroke, leaving 93 potentially eligible RCTs for inclusion.

1.

Flow diagram.

Of the 93 potentially eligible RCTs, we excluded 57 trials and added three ongoing trials. We therefore included in this version of the review 33 RCTs with a total of 3946 participants, 13 of which were included in the previous version (Cai 2002; Chen 1997; Duan 1997; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hu 1993; Huang 2002; Jin 1999; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Sze 2002; Wu 2002; Yu 1993), and 20 new trials (Chau 2009; Chen 2007; Chen 2015; Chen 2016a; Dong 2006; Guo 2016; Hsieh 2007; Lin 2005; Liu 2016; Mu 2008; Ou 2014; Pang 2006; Park 2005; Shen 2012a; Shen 2012b; Wang 2008; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2013; Zhang 2015; Zhu 2007).

Included studies

Of the 33 included RCTs, 28 were conducted in China (including Taiwan and Hong Kong), two in the UK, and three in Sweden. The mean age of participants ranged from 51 to 82 years. All RCTs included men and women. The rate of CT/MRI scanning was 100% in all except four trials (Chen 2016a; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001). Six trials included both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (Chen 2015; Pang 2006; Park 2005; Shen 2012a; Sze 2002; Wu 2002); two trials included participants with hemorrhagic stroke (Dong 2006; Guo 2016); the remaining trials included ischemic stroke, but for three of them we could not determine the subtype of stroke because of an incomplete rate of CT/MRI examination before entry (Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001).

Apart from sham/placebo acupuncture, participants randomized to sham control were given drug therapy (Shen 2012b), rehabilitation therapy (Chau 2009; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Park 2005), or both (Hopwood 2008; Johansson 2001), as was the acupuncture group. Participants randomized to open control also received drug therapy (Cai 2002; Chen 1997; Dong 2006; Duan 1997; Guo 2016; Huang 2002; Jin 1999; Lin 2005; Liu 2016; Mu 2008; Ou 2014; Wang 2008; Wu 2002; Yu 1993; Zhang 2005a; Zhu 2007), rehabilitation therapy (Chen 2015; Chen 2016a; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Johansson 1993), or both (Chen 2007; Hsieh 2007; Hu 1993; Pang 2006; Shen 2012a; Sze 2002; Zhang 2013; Zhang 2015), as did the acupuncture group, while no real/sham acupuncture was given.

All included trials described the acupuncture methods used. Time to the start of acupuncture treatment, method of treatment, time each session lasted, and number of sessions differed among trials (see table of Characteristics of included studies for details of each trial). Overall, three trials evaluated eye acupuncture (Chen 2007; Pang 2006; Wang 2008), four scalp acupuncture (Cai 2002; Dong 2006; Duan 1997; Yu 1993), eight body acupuncture (Chau 2009; Chen 1997; Chen 2015; Shen 2012a; Shen 2012b; Sze 2002; Zhang 2013; Zhu 2007), and one eye, scalp, and body acupuncture (Guo 2016). The remaining 17 trials used both scalp and body acupuncture treatment. The acupuncture program was not described for all, but three trials used "Xing Nao Kai Qiao" acupuncture methods (Shen 2012a; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015).

Among the 33 included RCTs, one included three groups ‐ specifically, one intervention and two control groups (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998). The remaining trials included two groups ‐ one intervention and one control group. In Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998, all participants received conventional stroke rehabilitation. Participants in the acupuncture group were given deep acupuncture via manual or electrical stimulation. Manual stimulation was used on the non‐paretic side until the special needle sensation, generally called "De Chi," was achieved. Electrical stimulation was used on the paretic side to achieve pronounced muscle contractions. Participants in the sham control group were given superficial acupuncture, by which needles were just placed under the skin and no manual or electrical stimulation was provided. Participants in the open control group were not given acupuncture.

The acupuncture treatment period was also heterogeneous among trials. Acupuncture treatment lasted one week in one trial (Huang 2002), approximately two weeks in nine trials (Cai 2002; Guo 2016; Lin 2005; Liu 2016; Ou 2014; Park 2005; Shen 2012a; Wang 2008; Yu 1993), approximately three weeks in five trials (Chen 1997; Chen 2016a; Mu 2008; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2013), approximately one month in nine trials (Chen 2015; Dong 2006; Duan 1997; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Hu 1993; Shen 2012b; Zhang 2015; Zhu 2007), 40 days in two trials (Jin 1999; Pang 2006), two months in one trial (Chau 2009), 10 weeks in four trials (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Sze 2002), three months in one trial (Chen 2007), and for an undetermined time in one trial (Wu 2002).

Thirteen included trials continued to follow participants after acupuncture treatment ended (Chen 2007; Chen 2016a; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Hu 1993; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Shen 2012a; Shen 2012b; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015), and the others stopped follow‐up once acupuncture treatment had ended. Follow‐up lasted one year in four trials (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001), and follow‐up was provided for six months in four trials (Hsieh 2007; Shen 2012b; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015). The remaining 25 trials followed participants for three months or less.

Excluded studies

We excluded 57 studies for the following reasons (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Randomization was questionable (Cai 2002a; Yin 2013; Zhang 1999).

It was not possible to include usable data for the meta‐analysis from the following: Fan 2014; Gu 2005; Guo 2006a; Jia 2007; Jiang 1998; Li 1999; Li 2000a; Li 2000b; Li 2001; Li 2009; Liu 2001; Liu 2002a; Liu 2002b; Liu 2003a; Liu 2010; Lv 2003; Sang 2013; Tang 1996; Wang 2001; Wang 2012a; Wang 2016; Xiong 2008; Xu 1997; Xu 2001; Yang 2001; Zhang 1996; Zhang 2011; Zhao 2000; Zhen 2011; Zhou 2000; Zhou 2002; Zhu 2013.

Data were questionable (data provided in the full text of the published paper were inconsistent) (Fu 2001).

The trial was confounded (Guo 2006b; Han 2016; Ma 1999; Pei 2001; Song 2016; Yun 2000; Zheng 1996).

Trial inclusion criteria provided no clear information on the course of stroke. Types of participants were questionable (Jiang 2009; Liu 2003b).

The trial aimed to assess effects of two kinds of acupuncture on acute stroke (acupuncture involving Du15 and Du16 in addition to other acupoints vs acupuncture involving other acupoints alone) (Li 1989).

Trials were quasi‐randomized, and the scale that was used to evaluate neurological function did not include a detailed description or reference, so reliability was uncertain (Li 2008).

Participants who were within three days after stroke onset were included in the abstract, and participants who were within seven days after stroke onset were included in the main body of the text. In addition, the main text describes that 120 participants were enrolled and randomized in this study, discusses only 90 participants in the results section, and provides no information on the remaining 30 participants. Trial data were questionable (Wang 2007).

Trial inclusion criteria did not define the course of acute stroke (Liu 2015; Ruan 2012; Zhu 2012).

Trials provided sparse information on acupoints, how to stimulate, how long each session lasted, and how many sessions were provided. In addition, it was not possible to include usable data in the analysis (Wang 2014).

Acupuncture points were stimulated by using an adhesive surface electrode (Wong 1999).

This trial described methods that were inconsistent with normal clinical practice. In this trial,participants with acute ischemic stroke and Barthel Index (BI) < 70 were included and randomized in the outpatient department. It was difficult to perform this trial in China. The type of study was questionable (Yu 2003).

The trial included patients with stroke with subarachnoid hemorrhage (Xia 2016).

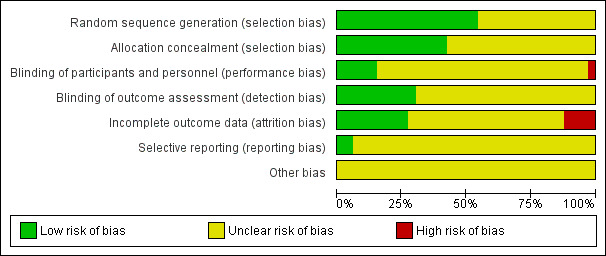

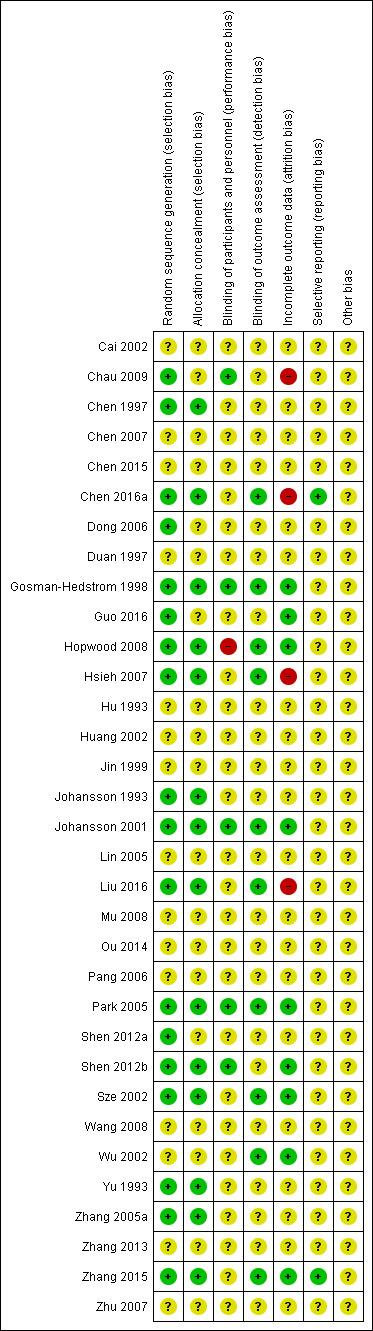

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

All included trials explicitly stated that randomization occurred. Eighteen trials reported the method of randomization (Chau 2009; Chen 1997; Chen 2016a; Dong 2006; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Guo 2016; Hsieh 2007; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Park 2005; Shen 2012a; Shen 2012b; Sze 2002; Yu 1993; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015), 14 trials reported concealment of allocation (Chen 2007; Chen 2016a; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Park 2005; Shen 2012b; Sze 2002; Yu 1993; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015), and the remaining trials did not report how participants were randomized or how the allocation sequence was generated or concealed. We evaluated methods of randomization and concealment as introducing unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Eleven trials reported that treatment was blinded to both participants and outcome assessors (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Johansson 2001; Park 2005), participants (Chau 2009; Shen 2012b), or outcome assessors (Chen 2016a; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Liu 2016; Sze 2002; Wu 2002). The other trials failed to report blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Seven trials reported the numbers lost to follow‐up (Chen 2016a; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 2001; Shen 2012b; Zhang 2015). The rate of loss to follow‐up ranged from 1% to 33.3%. Six trials noted the number of withdrawals (Chau 2009; Hopwood 2008; Liu 2016; Park 2005; Sze 2002; Wu 2002). The rate of withdrawals ranged from 1.9% to 15.5%. All participants in the remaining trials completed treatment and follow‐up.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting bias was not clear because the protocols of 31 included RCTs were not available; protocols for only two trials were available (Chen 2016a; Zhang 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

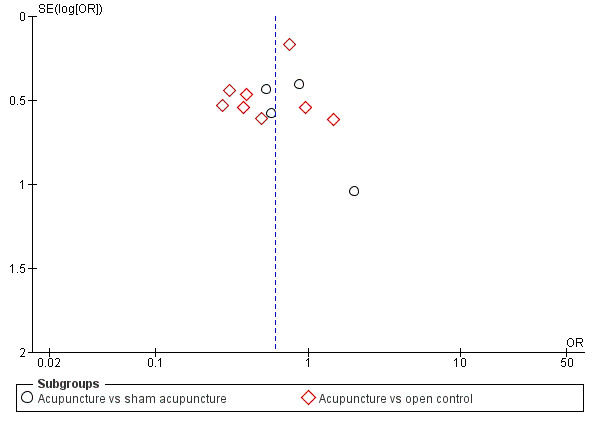

The funnel plot with large number of trials investigating death or dependency at the end of follow‐up showed a slightly asymmetrical funnel distribution, so publication bias may be present (Figure 2).

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Acupuncture versus control, outcome: 1.1 Death or dependency at end of follow‐up.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcome

Death or dependency at end of follow‐up

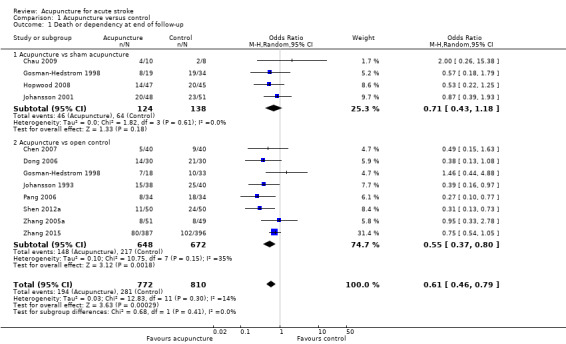

Eleven trials with a total of 1582 participants measured this outcome at the end of follow‐up (Chau 2009; Chen 2007; Dong 2006; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Pang 2006; Shen 2012a; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015). Investigators defined dependency as BI ≤ 60 (of a potential total of 100; Chen 2007; Chau 2009; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Shen 2012a; Zhang 2015), BI ≤ 70 (of a potential total of 100; Dong 2006; Pang 2006), or BI ≤ 12 (of a potential total of 20; Hopwood 2008), or by trialists' own definition (Zhang 2005a). Overall, participants in the acupuncture group were reported as less likely to be dead or dependent compared with those in the control group (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.79; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome [NNTB] = 11; I2 = 14%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1). We downgraded the evidence to very low quality for inconsistency and risk of bias. Also, when acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture alone, the difference in death or dependency between the two groups was not significant (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.18; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 1 Death or dependency at end of follow‐up.

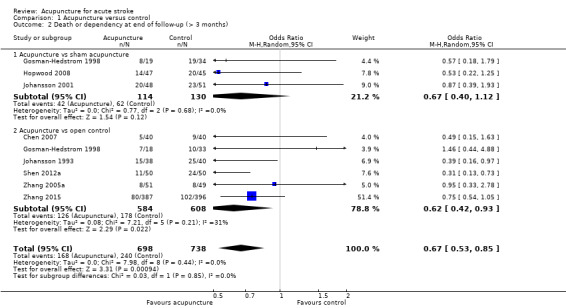

Eight of 11 trials with 1436 participants followed participants for at least three months (Chen 2007; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Shen 2012a; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015). Data show a significant effect of acupuncture on reducing death or dependency (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.85; I2 = 0%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2). When acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture alone, the difference between the two groups was not significant (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.12; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 2 Death or dependency at end of follow‐up (> 3 months).

Secondary outcomes

Death or institutional care at end of follow‐up

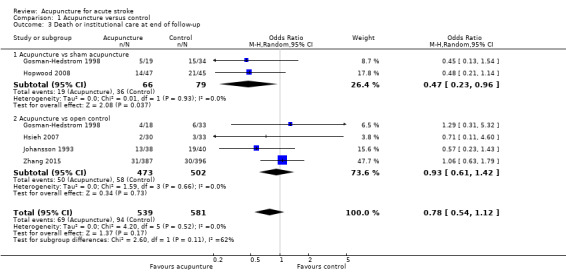

Data for this outcome were available for five trials with 1120 participants (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 1993; Zhang 2015). All five trials followed up with participants for longer than three months after stroke. The numbers of participants living at home and needing extensive family support were not available. The numbers of participants living in rehabilitation units, nursing homes/old people's homes, and acute hospitals were included in the analysis as numbers requiring institutional care. Overall, data show a non‐significant difference between acupuncture and control groups with regard to the outcome of death or institutional care (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.12; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). When acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture, data show a significant trend toward fewer deaths among participants and less need for institutional care (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.96; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 3 Death or institutional care at end of follow‐up.

Changes in neurological deficit score and motor function score at end of treatment period and at end of follow‐up (> three months)

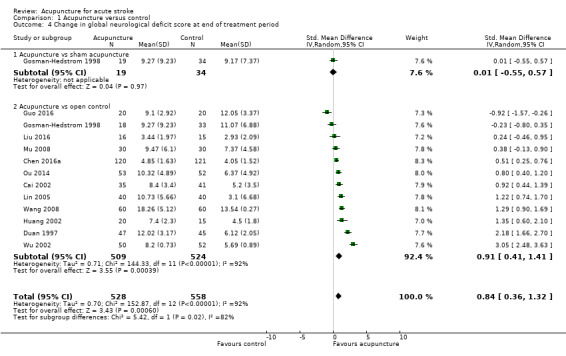

Changes in global neurological deficit score at the end of the treatment period could be extracted from 12 studies with a total of 1086 participants (Cai 2002; Chen 2016a; Duan 1997; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Guo 2016; Huang 2002; Lin 2005; Liu 2016; Mu 2008; Ou 2014; Wang 2008; Wu 2002). Global neurological function was measured by the MESSS (Cai 2002; Duan 1997; Guo 2016; Huang 2002; Lin 2005; Mu 2008; Ou 2014; Wang 2008; Wu 2002), the NIHSS (Chen 2016a; Liu 2016), or the SSS (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998). Overall, improvement in neurological deficit was more significant in the acupuncture group than in the control group (SMD 0.84, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.32; I2 = 92%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4). We downgraded the evidence for this outcome to very low quality owing to both risk of bias and inconsistency. We noted no significant difference in changes in global neurological deficit score when acupuncture was compared with sham control (SMD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.57; I2 not applicable). Only two trials measured long‐term changes in global neurological deficit score (> three months), and the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (weighted mean difference [WMD] ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.37 to 0.33) (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Liu 2016).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 4 Change in global neurological deficit score at end of treatment period.

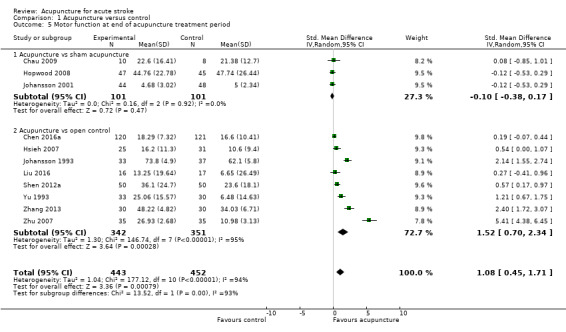

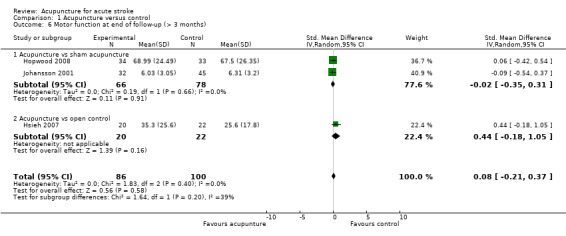

Data showing changes in motor function score at the end of the treatment period were available for 11 studies with 895 participants (Chau 2009; Chen 2016a; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Shen 2012a; Yu 1993; Zhang 2013; Zhu 2007). Researchers measured motor function using the Fugl‐Meyer Assessment (Chau 2009; Chen 2016a; Hsieh 2007; Liu 2016; Shen 2012a; Zhang 2013; Zhu 2007), the Motricity Index (Hopwood 2008), motor function score (Johansson 1993), the Rivermead Mobility Index (Johansson 2001), or a mobility index (Yu 1993). Similarly, data show a significant trend toward greater improvement in motor function in the acupuncture group than in the control group (SMD 1.08, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.71; I2 = 94%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5). We downgraded the evidence for this outcome to low quality owing to risk of bias and inconsistency. Also the difference was non‐significant when acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture alone (SMD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.17; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence). Three studies provided data on long‐term motor function score (> three months); the difference in changes in motor function score between acupuncture and control groups was not significant (Analysis 1.6) (Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 2001).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 5 Motor function at end of acupuncture treatment period.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 6 Motor function at end of follow‐up (> 3 months).

We noted significant heterogeneity for the outcomes of changes in global neurological deficit score and motor function at the end of the treatment period, which may have been due to differences in scales, times of evaluation from stroke onset, and control groups.

Death within first two weeks and during the whole follow‐up period

Eighteen studies with 1612 participants provided data on death within the first two weeks. Overall, few participants died (acupuncture group 6/799, 0.75%; control group 8/813, 0.98%) and data show no significant differences between groups (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.55; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.7). We downgraded the evidence for this outcome to low quality owing to risk of bias in the included trials. Also, when acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture alone, the difference in death between the two groups was not significant (OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.27 to 5.26; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 7 Death within first 2 weeks.

Data on death during the whole follow‐up period were available for 22 studies with 2865 participants. Similar to data on death within the first two weeks, a small number of participants in both the acupuncture group (62/1422, 4.36%) and the control group (65/1443, 4.50%) died (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.58; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.8). We downgraded the evidence for this outcome to low quality owing to risk of bias in included trials. Also, when acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture alone, the difference in death between the two groups was not significant (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.72; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 8 Death during whole follow‐up period.

Quality of life (QOL) at the end of follow‐up

Six studies investigated the effects of acupuncture on QOL. One trial used the EuroQoL–5‐Dimensional Forma (EQ‐5D) and the EuroQoL–Visual Analog Scale (EQ‐VAS) (Park 2005). Results of this trial suggest that acupuncture was not superior to sham treatment. Another study used the Stroke‐Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS‐QOL) to study QOL at six months after stroke; results indicate that acupuncture may improve QOL at six months (Shen 2012b). The remaining four trials used Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) scores to investigate this outcome (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001). However, the standard deviations for NHP in the four trials were not available, so we could not perform a meta‐analysis for this outcome. Regarding the dimensions of pain and sleep, none of the trials showed a significant difference between the acupuncture group and the control group. Scores on energy show that acupuncture treatment was superior to control treatment; the difference was significant in two trials (Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993), and it was non‐significant in one trial (Johansson 2001). Also, data show a significant difference between groups with regard to the dimensions of mobility (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Johansson 1993), emotional reaction (Johansson 1993), and social isolation (Johansson 1993).

Numbers with adverse events related to acupuncture treatment

Among the 33 included trials, only one trial reported severe AEs, which occurred in both acupuncture and control groups, and noted no significant difference (Zhang 2015). Thirteen trials reported AEs that were directly related to acupuncture (Chau 2009; Chen 2015; Dong 2006; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hu 1993; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Park 2005; Shen 2012b; Sze 2002; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015). Of 1037 participants in the acupuncture group, 64 (6.2%) were observed to have AEs and 14 (1.4%) of them discontinued acupuncture because of pain (Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015), erysipeloid arm infection (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998), and bruising from handling (Hopwood 2008). Common reported AEs of acupuncture included seizure (Park 2005), pain (Shen 2012b; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015), infection (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Zhang 2015), faint (Shen 2012b; Liu 2016; Zhang 2015), dizziness (Hu 1993; Zhang 2015), high blood pressure (Shen 2012b), and bruising at acupoints (two participants who were taking anticoagulants) (Hopwood 2008; Sze 2002). Five of the 13 trials above also recorded AEs related to sham acupuncture, which occurred in 8.0% (24/298) of participants. Data show no significant difference in the proportion of participants with AEs between acupuncture and sham treatment groups (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.16; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.9). In Analysis 1.9, we pooled data only from trials that involved sham acupuncture. Differences in AEs between acupuncture and sham acupuncture were comparable. Given that participants in the open control group were not given acupuncture, we did not pool data from trials with open control for the meta‐analysis.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus control, Outcome 9 Adverse events during treatment period.

Sensitivity analyses

Excluding trials with open control

We included in the analysis six trials with placebo/sham acupuncture (Chau 2009; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Johansson 2001; Park 2005; Shen 2012b). Data show no beneficial effects of acupuncture for any outcomes except death or needing institutional care (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.96; low‐quality evidence).

Excluding trials in which adequate concealment of allocation was unclear

We included in the analysis 14 trials with adequate concealment of allocation (Chen 1997; Chen 2016a; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Park 2005; Shen 2012b; Sze 2002; Yu 1993; Zhang 2005a; Zhang 2015). Fewer participants in the acupuncture group than in the control group were reported to be dead or dependent (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.93). However, significant effects of acupuncture were not observed for other outcomes.

Excluding trials in which the outcome evaluation was not blinded

For this analysis, we pooled data from 12 trials (Chau 2009; Chen 2016a; Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Hopwood 2008; Hsieh 2007; Johansson 2001; Liu 2016; Park 2005; Shen 2012b; Sze 2002; Wu 2002; Zhang 2015). The likelihood of being dead or dependent was lower in the acupuncture group than in the control group (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.00). Data show no statistically significant effects of acupuncture for other outcomes.

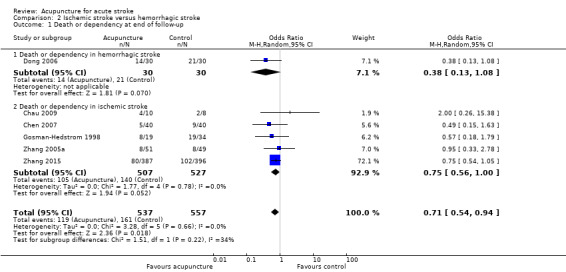

Subgroup analyses

Effects in ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke

Of the 33 included trials, six trials included both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (Chen 2015; Pang 2006; Park 2005; Shen 2012a; Sze 2002; Wu 2002). Only two trials included participants with hemorrhagic stroke (Dong 2006; Guo 2016). The remaining trials included participants with ischemic stroke, but in three of them, several participants did not undergo a brain CT/MRI before entry (Hopwood 2008; Johansson 1993; Johansson 2001). Data show a non‐significant subgroup difference between the two groups of trials with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke for the primary outcome (I2 = 33.7%, P = 0.22; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Ischemic stroke versus hemorrhagic stroke, Outcome 1 Death or dependency at end of follow‐up.

Effects of time of the start of acupuncture (within and after 10 days from stroke onset)

We could not perform this subgroup analysis because all trials included participants within 10 days of stroke onset.

Effects of stroke severity determined by NIHSS, SSS, CNS, or ESS, or by trialists' own definition at baseline

We could not perform this subgroup analysis because all trials included participants with different stroke severity.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included in this updated review 33 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with a total of 3946 participants; we identified 20 new trials since publication of the previous version of the review. Although most trials assessed effects of acupuncture on activities of daily living (ADL), data on death or dependency were available from 11 trials with 1582 participants. Across trials using any control comparison, participants in the acupuncture group were reported to be less likely to be dead or dependent at the end of follow‐up and to have improved neurological deficits, especially for motor function. Investigators provided no evidence of a difference for other trial outcomes. However, all these results are uncertain owing to very low‐quality evidence and were not confirmed in sensitivity analyses using only sham acupuncture controls. Thus we must conclude that these apparent improvements in outcome with acupuncture in acute stroke are confounded by the high risk of bis related to use of open controls.

The reported incidence of adverse events directly related to acupuncture was about 6.2%, and 1.4% of participants discontinued acupuncture owing to intolerable pain, infection, and bruising at acupoints. Adverse events were reported in 8% of participants who received sham acupuncture. Unfortunately, reporting of adverse events was incomplete.

In view of the many uncertainties related to quality of the evidence, additional large, high‐quality randomized trials are required to confirm or refute the effects of acupuncture in acute stroke.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In this review, we focused on the effects of acupuncture on ADL when used in the acute stage of stroke. Of 33 included trials,11 RCTs with a total of 1582 participants measured this outcome, and most trials evaluated the effects of acupuncture on neurological deficits. Acupuncture methods used in the included trials are common in clinical practice.

The present review had several limitations.

Follow‐up in most of the included trials was completed within three months. With regard to recovery after stroke, long‐term effects should be evaluated.

Heterogeneity among the included trials was huge. Potential reasons were (1) different outcome scales were used across trials; and (2) acupuncture methods and the time of starting acupuncture treatment varied.

Only a small number of trials assessed the effects of acupuncture used in acute hemorrhagic stroke.

In the analysis of effects of acupuncture on the primary outcome, only two of eight trials with open control clearly stated blinding of outcome assessment (Gosman‐Hedstrom 1998; Zhang 2015). The remaining six trials did not report sufficient information to permit judgement on detection bias (Chen 2007; Dong 2006; Johansson 1993; Pang 2006; Shen 2012a; Zhang 2005a). Close inspection of other results suggest that this finding reflects the number of participants classified as dependent rather than the number who have died because the data show few deaths (with an odds ratio [OR] of 1.08) (Analysis 1.8). The composite of death/institutional care also shows little evidence of an effect (Analysis 1.3). Measures of dependency are susceptible to performance/detection bias, which is showing up strongly in open control trials.

Given that only 12 of the 33 included trials reported sufficient information for judgement of performance/detection bias, we downgraded the evidence for the primary outcome and for secondary outcomes. Future studies with larger sample sizes, clear information on methods of randomization and concealment of allocation, and statements of whether participants, personnel, and outcome assessors were blinded are required to confirm the effects and safety of acupuncture.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence varied across the 33 included trials. Overall, 18 trials reported the method of randomization, 14 adequately concealed the sequence of randomization, and 12 reported that treatment was blinded to participants or outcome assessors, or both. Seven trials performed intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis.

According to the five GRADE considerations, the quality of the body of evidence was low for the outcome of death at end of follow‐up and long‐term follow‐up (three months or longer) and was very low for the other outcomes. The main reasons for downgrading evidence included risk of bias in included trials, inconsistency, and imprecision (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Potential biases in the review process

We used a comprehensive search strategy for this updated review. We prepared a funnel plot for the primary outcome of death or dependency and found a slightly asymmetrical funnel distribution, which indicated the possibility of publication bias (Figure 2).

The Characteristics of included studies tables show risk of bias, as summarized in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several systematic reviews of acupuncture for stroke have been published before this updated review. One systematic review investigated the effects of long‐term "Xingnao Kaiqiao needling" in people with ischemic stroke (Yang 2015). We included two trials with 126 participants in the meta‐analyses on disability, results of which indicated that "Xingnao Kaiqiao needling" could reduce the poststroke disability rate, which is consistent with the findings of our review. Another systematic review investigated the effect of acupuncture for the outcome of death or dependency (Zheng 2011), whereas no trial in this review reported this outcome. A third systematic review, which included patients with stroke in both the acute and the non‐acute stage, demonstrated the efficacy of acupuncture in poststroke rehabilitation, whereas review authors did not report the effects of acupuncture on ADL and in the acute stage alone (Wu 2010).

Three systematic reviews evaluated scalp acupuncture for people with acute ischemic stroke (Wang 2012b), acute hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (Zheng 2011), or stroke (Bai 2015). All three reviews drew similar conclusions that scalp acupuncture was useful in improving neurological deficits. Six trials included in one review focused on the effect of scalp acupuncture on neurological deficit scores in acute ischemic stroke (Wang 2012b); only one trial stated the method of randomization, and no trial reported allocation concealment or the blinding procedure. Furthermore, selective reporting bias might be present in the RCTs included in this review, characterized as co‐intervention reported and similarity of baseline (Wang 2012b). In Bai 2015, data on changes in neurological deficit score and motor function were available, and this trial did not report the method of randomization, allocation concealment, or the blinding procedure. Thus the results of these two reviews should be interpreted with caution because the included trials were of low quality (Bai 2015; Wang 2012b). In the review of acupuncture for acute intracerebral hemorrhage (Zheng 2011), investigators assessed neurological deficit improvement by using the rate of reduction in neurological deficit scores at baseline rather than changes in neurological deficit score as used in the present review.

Two systematic reviews that investigated sham‐controlled RCTs found no positive effect of acupuncture on functional recovery after stroke (Kong 2010; Wu 2010), which was consistent with findings of the subgroup analysis reported in the present review. However, we do not think that sham acupuncture as the control is necessary in a pragmatic trial because sham acupuncture may have an underlying physiological effect (Bao 2014; Moffet 2009; Zhang 2015).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In this review, the apparent reduction in dependency and improvement in neurological recovery with acupuncture in acute stroke are confounded by risk of bias related to use of open controls. Adverse events with acupuncture were generally reported to be minor and usually did not result in stopping treatment.

Implications for research.

Among the 33 included trials, only 18 reported information about randomization and 12 reported blinding. Future studies, with larger sample sizes, clear information on methods of randomization and concealment of allocation, and statements on whether participants, personnel, and outcome assessors were blinded, are required to assess the effects and safety of acupuncture. Future studies should pay specific attention to the effects of acupuncture on long‐term functional outcomes. Notably, only two trials in this updated review investigated the effects of acupuncture on hemorrhagic stroke. Data show possible differences between symptoms and consequently between the results of acupuncture in patients with ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke; thus wider research studies in the future should be sure to include people with hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, further reliable studies in other ethnic populations (alongside the Asian ones) are required to identify population‐specific response differences.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 December 2017 | Amended | The structure and content of this review have been extensively revised in line with feedback from the Cochrane Stroke Group and the Cochrane Editorial Unit. Comparisons were restructured as (1) acupuncture vs any control (open control or sham acupuncture), and (2) acupuncture vs sham acupuncture. |

| 21 February 2017 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This updated review extends the safety results for acupuncture in acute stroke and indicates that acupuncture may improve activities of daily living. |

| 21 February 2017 | New search has been performed | We have included in this update 20 new trials with 2780 participants, bringing the total number of included studies to 33 and included participants to 3946. The findings presented in this updated review show that acupuncture could be used for treatment of patients with acute stroke, but this remains to be confirmed by large sample sizes and high‐quality trials, whereas results of the previous review did not support the routine use of acupuncture for people with acute stroke. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Hazel Fraser (Managing Editor, Cochrane Stroke Group) for the search of the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register, and Brenda Thomas (Trials Search Co‐ordinator) and Joshua Cheyne (Information Specialist) for the searches of CINAHL and AMED databases. We acknowledge with thanks the useful comments and the work of Prof Peter Langhorne, who spent time helping to revise this updated review. We also thank Valentina Assi, Joshua Cheyne, Maree Hackett, Hongmei Wu, Julie Gildie, Odie Geiger, and Heather Goodare for their many useful comments. We thank Prof Ming Liu for her contribution to previous versions of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL

1 exp cerebrovascular disorders/ 2 (stroke$ or poststroke$ or cva$).tw. 3 (cerebrovascular$ or cerebral vascular).tw. 4 (cerebral or cerebellar or brainstem or vertebrobasilar).tw. 5 (infarct$ or isch?emi$ or thrombo$ or apoplexy or emboli$).tw. 6 4 and 5 7 (cerebral or intracerebral or intracranial or parenchymal).tw. 8 (brain or intraventricular or brainstem or cerebellar).tw. 9 (infratentorial or supratentorial or subarachnoid).tw. 10 7 or 8 or 9 11 (haemorrhage or haemorrhage or hematoma or hematoma).tw. 12 (bleeding or aneurysm).tw. 13 11 or 12 14 10 and 13 15 thrombo$.tw. 16 (intracranial or sinus or (venous adj5 sinus$) or (sagittal adj5 venous) or (sagittal adj5 vein)).tw. 17 15 and 16 18 1 or 2 or 3 or 6 or 14 or 17 19 acupuncture/ 20 exp acupuncture therapy/ 21 electroacupuncture/ 22 meridians/ 23 acupuncture points/ 24 acupuncture$.tw. 25 (electroacupuncture or electro‐acupuncture).tw. 26 acupoints.tw. 27 ((meridian or non‐meridian or trigger) adj10 point$).tw. 28 or/19‐27 29 18 and 28

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE

1 exp cerebrovascular disorders/ 2 (stroke$ or poststroke$ or cva$).tw. 3 (cerebrovascular$ or cerebral vascular).tw. 4 (cerebral or cerebellar or brainstem or vertebrobasilar).tw. 5 (infarct$ or isch?emi$ or thrombo$ or apoplexy or emboli$).tw. 6 4 and 5 7 (cerebral or intracerebral or intracranial or parenchymal).tw. 8 (brain or intraventricular or brainstem or cerebellar).tw. 9 (infratentorial or supratentorial or subarachnoid).tw. 10 7 or 8 or 9 11 (haemorrhage or haemorrhage or hematoma or hematoma).tw. 12 (bleeding or aneurysm).tw. 13 11 or 12 14 10 and 13 15 thrombo$.tw. 16 (intracranial or sinus or (venous adj5 sinus$) or (sagittal adj5 venous) or (sagittal adj5 vein)).tw. 17 15 and 16 18 1 or 2 or 3 or 6 or 14 or 17 19 acupuncture/ 20 exp acupuncture therapy/ 21 electroacupuncture/ 22 meridians/ 23 acupuncture points/ 24 acupuncture$.tw. 25 (electroacupuncture or electro‐acupuncture).tw. 26 acupoints.tw. 27 ((meridian or non‐meridian or trigger) adj10 point$).tw. 28 or/19‐27 29 18 and 28

Appendix 3. Search strategy for Embase

1 exp cerebrovascular disease/ 2 (stroke$ or poststroke$ or cva$).tw. 3 (cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular).tw. 4 (cerebral or cerebellar or brainstem or vertebrobasilar).tw. 5 (infarct$ or isch?emi$ or thrombo$ or apoplexy or emboli$).tw. 6 4 and 5 7 (cerebral or intracerebral or intracranial or parenchymal).tw. 8 (brain or intraventricular or brainstem or cerebellar).tw. 9 (infratentorial or supratentorial).tw. 10 7 or 8 or 9 11 (haemorrhage or haemorrhage or hematoma or hematoma).tw. 12 10 and 11 13 1 or 2 or 3 or 6 or 12 14 exp acupuncture/ 15 acupunctur$.tw. 16 (electroacupuncture or electro‐acupuncture).tw. 17 acupoint$.tw. 18 ((meridian or non‐meridian or trigger) adj10 point$).tw. 19 or/14‐18 20 13 and 19

Appendix 4. Search strategy for CINAHL

S1 ‐(MH "Cerebrovascular Disorders") OR (MH "Basal Ganglia Cerebrovascular Disease+") OR (MH "Carotid Artery Diseases+") OR (MH "Cerebral Ischemia+") OR (MH "Cerebral Vasospasm") OR (MH "Intracranial Arterial Diseases+") OR (MH "Intracranial Embolism and Thrombosis") OR (MH "Intracranial Hemorrhage+") OR (MH "Stroke") OR (MH "Vertebral Artery Dissections")

S2 ‐(MH "Stroke Patients") OR (MH "Stroke Units")

S3 ‐TI ( stroke* or poststroke or apoplex* or cerebral vasc* or brain vasc* or cerebrovasc* or cva* or SAH ) or AB ( stroke* or poststroke or apoplex* or cerebral vasc* or brain vasc* or cerebrovasc* or cva* or SAH )

S4 ‐TI ( brain or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracran* or intracerebral) or AB ( brain or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracran* or intracerebral)

S5 ‐TI ( ischemi* or ischaemi* or infarct* or thrombo* or emboli* or occlus*) or AB ( ischemi* or ischaemi* or infarct* or thrombo* or emboli* or occlus*)

S6 ‐S4 and S5

S7 ‐TI ( brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracran* or subarachnoid ) or AB ( brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracran* or subarachnoid )

S8 ‐TI ( haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or haematoma* or hematoma* or bleed* ) or AB ( haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or haematoma* or hematoma* or bleed* )

S9 ‐S7 and S8

S10 ‐S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S6 OR S9

S11 ‐(MH "Acupuncture") OR (MH "Acupuncture Analgesia") OR (MH "Acupuncture Anesthesia") OR (MH "Acupuncture, Ear") OR (MH "Electroacupuncture") OR (MH "Meridians") OR (MH "Acupuncture Points") OR (MH "Acupuncturists") OR (MH "Trigger Point")

S12 ‐TI (acupuncture* or electroacupuncture or electro‐acupuncture or acupoint* or meridians or needling) OR AB (acupuncture* or electroacupuncture or electro‐acupuncture or acupoint* or meridians or needling)

S13 ‐TI ((meridian or non‐meridian or trigger) N10 point*) or AB ((meridian or non‐meridian or trigger) N10 point*)

S14 ‐S11 OR S12 OR S13

S15 ‐S10 AND S14

Appendix 5. Search strategy for AMED

1. cerebrovascular disorders/ or cerebral hemorrhage/ or cerebral infarction/ or cerebral ischemia/ or cerebrovascular accident/ or stroke/

2. (stroke or poststroke or post‐stroke or cerebrovasc$ or brain vasc$ or cerebral vasc$ or cva$ or apoplex$ or SAH).tw.

3. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracran$ or intracerebral) adj5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$)).tw.

4. ((brain$ or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or intracerebral or intracranial or subarachnoid) adj5 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or haematoma$ or hematoma$ or bleed$)).tw.

5. or/1‐4

6. acupuncture/ or acupuncture therapy/ or acupoints/ or neiguan/ or acupuncture analgesia/ or ear acupuncture/ or electroacupuncture/ or meridians/ or needling/ or scalp acupuncture/

7. (acupuncture$ or electroacupuncture or electro‐acupuncture or acupoint$ or meridians or needling).tw.

8. ((meridian or non‐meridian or trigger) adj10 point$).tw.

9. 6 or 7 or 8

10. 5 and 9

Appendix 6. Search terms for the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry

English:

Target disease: acute stroke or acute ischemic stroke or acute intracerebral hemorrahge

Intervention: acupuncture

Chinese:

研究疾病名称:急性脑卒中

干预措施:针刺

Appendix 7. Search strategy for the WHO International Trials Registry Platform

acupuncture and acute stroke

Appendix 8. Search strategy for Clinicaltrials.gov

acupuncture and acute stroke

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Acupuncture versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death or dependency at end of follow‐up | 11 | 1582 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.46, 0.79] |

| 1.1 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 4 | 262 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.43, 1.18] |

| 1.2 Acupuncture vs open control | 8 | 1320 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.37, 0.80] |

| 2 Death or dependency at end of follow‐up (> 3 months) | 8 | 1436 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.53, 0.85] |

| 2.1 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 3 | 244 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.40, 1.12] |

| 2.2 Acupuncture vs open control | 6 | 1192 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.42, 0.93] |

| 3 Death or institutional care at end of follow‐up | 5 | 1120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.54, 1.12] |

| 3.1 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 2 | 145 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.23, 0.96] |

| 3.2 Acupuncture vs open control | 4 | 975 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.61, 1.42] |

| 4 Change in global neurological deficit score at end of treatment period | 12 | 1086 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.36, 1.32] |

| 4.1 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 1 | 53 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.55, 0.57] |

| 4.2 Acupuncture vs open control | 12 | 1033 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.41, 1.41] |

| 5 Motor function at end of acupuncture treatment period | 11 | 895 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.45, 1.71] |

| 5.1 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 3 | 202 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.38, 0.17] |

| 5.2 Acupuncture vs open control | 8 | 693 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.70, 2.34] |

| 6 Motor function at end of follow‐up (> 3 months) | 3 | 186 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.21, 0.37] |

| 6.1 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 2 | 144 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.35, 0.31] |

| 6.2 Acupuncture vs open control | 1 | 42 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [‐0.18, 1.05] |