Abstract

Background

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), sometimes referred to as chronic otitis media (COM), is a chronic inflammation and infection of the middle ear and mastoid cavity, characterised by ear discharge (otorrhoea) through a perforated tympanic membrane. The predominant symptoms of CSOM are ear discharge and hearing loss.

Topical antiseptics, one of the possible treatments for CSOM, inhibit the micro‐organisms that may be responsible for the infection. Antiseptics can be used alone or in addition to other treatments for CSOM, such as antibiotics or ear cleaning (aural toileting). Antiseptics or their application can cause irritation of the skin of the outer ear, manifesting as discomfort, pain or itching. Some antiseptics (such as alcohol) may have the potential to be toxic to the inner ear (ototoxicity), with a possible increased risk of causing sensorineural hearing loss, dizziness or tinnitus.

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical antiseptics for people with chronic suppurative otitis media.

Search methods

The Cochrane ENT Information Specialist searched the Cochrane ENT Register; Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4, via the Cochrane Register of Studies); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid Embase; CINAHL; Web of Science; ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the search was 1 April 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with at least a one‐week follow‐up involving patients (adults and children) who had chronic ear discharge of unknown cause or CSOM, where the ear discharge had continued for more than two weeks.

The interventions were any single, or combination of, topical antiseptic agent of any class, applied directly into the ear canal as ear drops, powders or irrigations, or as part of an aural toileting procedure.

Two main comparisons were topical antiseptics compared to: a) placebo or no intervention; and b) another topical antiseptic (e.g. topical antiseptic A versus topical antiseptic B).

Within each comparison we separated studies where both groups of patients had received topical antiseptics a) alone or with aural toileting and b) on top of antibiotic treatment.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard Cochrane methodological procedures. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome.

Our primary outcomes were: resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear' (whether otoscopically confirmed or not), measured at between one week and up to two weeks, two weeks to up to four weeks, and after four weeks; health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument; ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation. Secondary outcomes included hearing, serious complications and ototoxicity measured in several ways.

Main results

Five studies were included. It was not possible to calculate the total number of participants as two studies only provided the number of ears included in the study.

A. Topical antiseptic (boric acid) versus placebo or no treatment (all patients had aural toileting)

Three studies compared topical antiseptics with no treatment, with one study reporting results we could use (254 children; cluster‐RCT). This compared the instillation of boric acid in alcohol drops versus no ear drops for one month (both arms used daily dry mopping). We made adjustments to the data to account for the intra‐cluster correlation. The very low certainty of the evidence means it is uncertain whether or not treatment with an antiseptic leads to an increase in resolution of ear discharge at both four weeks (risk ratio (RR) 1.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20 to 3.16; 174 participants) and at three to four months (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.47; 180 participants). This study narratively described no differences in suspected ototoxicity or hearing outcomes between the arms (very low‐certainty evidence). None of the studies reported results for health‐related quality of life, adverse effects or serious complications.

B. Topical antiseptic A versus topical antiseptic B

Two studies compared different antiseptics but only one (93 participants), comparing a single instillation of boric acid powder with daily acetic acid ear drops, provided any information for this comparison. The very low certainty of the evidence means that it is uncertain whether more patients had resolution of ear discharge with boric acid powder compared to acetic acid at four weeks (RR 2.61, 95% CI 1.51 to 4.53; 93 participants), or whether there was a difference between the arms with respect to ear discomfort due to the low number of reported events (RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.81; 93 participants). Narratively, the study reported no difference in hearing outcomes between the groups. None of the included studies reported any of the other primary or secondary outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Due to paucity of the evidence and the very low certainty of that which is available the effectiveness and safety profile of antiseptics in the treatment of CSOM is uncertain.

Plain language summary

Topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review is to find out whether topical antiseptics are effective compared to placebo or no treatment in treating chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM). The review also looked to see whether one topical antiseptic was more effective than the others. The Cochrane Review authors collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question.

Key messages

Due to a lack of trials and the very low certainty of the evidence that is available, the effectiveness of antiseptics in the treatment of CSOM is unclear. Adverse effects were not well reported in the studies.

What was studied in the review?

Chronic suppurative otitis media is a long‐term (chronic) swelling and infection of the middle ear, with ear discharge (otorrhoea) through a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum). The main symptoms are ear discharge and hearing loss.

Topical antiseptics (antiseptics put directly into the ear as ear drops or as a powder) are sometimes used as a treatment for CSOM. Topical antiseptics kill or stop the growth of the micro‐organisms that may be responsible for the infection. Topical antiseptics can be used on their own or added to other treatments for CSOM, such as antibiotics or ear cleaning (aural toileting). Applying topical antiseptics can cause irritation of the skin within the outer ear, which may cause discomfort, pain or itching. Some antiseptics (such as alcohol) can be toxic to the inner ear (ototoxicity), which means they may cause irreparable hearing loss (sensorineural), dizziness or ringing in the ear (tinnitus).

What are the main results of the review?

We found five studies but it was not possible to tell how many participants were included as two studies only reported how many ears were treated. Different types of antiseptics were used: some used ear drops and some used powders.

Topical antiseptic (boric acid) versus no treatment (with a background treatment of ear cleaning)

One study (254 children) compared using boric acid in alcohol ear drops with no topical antiseptic treatment. All children had their ears cleaned daily using cotton wool sticks (dry mopping). The very low certainty of the evidence means that it is unclear whether or not treatment with an antiseptic leads to an increase in resolution of ear discharge at four weeks or at three to four months compared with the group who did not receive any topical antiseptic. The study reported that there was no difference between the two treatment groups in hearing or suspected ototoxicity. There was no information for any of the other outcomes.

Comparison of topical antiseptic agents

One study (93 participants) compared a single dose of boric acid powder with daily acetic acid ear drops. The very low certainty of the evidence means that it is unclear if boric acid leads to an increase in resolution of ear discharge compared to daily acetic acid drops at four weeks. It was uncertain if one group had more ear discomfort than the other group. There was no information for any of the other outcomes.

How up to date is the review?

The evidence is up to date to April 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Topical antiseptic compared to no treatment for chronic suppurative otitis media.

| Topical antiseptic compared to no treatment for chronic suppurative otitis media | |||||||

| Patient or population: chronic suppurative otitis media Setting: community setting, Malawi Intervention: topical antiseptic (boric acid in alcohol ear drops and daily dry mopping) Comparison: no topical antiseptic (daily dry mopping alone) | |||||||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without topical antiseptic | With topical antiseptic | Difference | |||||

| Resolution of ear discharge (between 1 week and up to 2 weeks) ‐ not reported | — | — | — | — | — | — | No study reported this outcome at this time point |

| Resolution of ear discharge (4 weeks or more) Follow‐up: 3 to 4 months |

180 (1 RCT) |

RR 1.73 (1.21 to 2.47) | Study population | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | Boric acid in alcohol ear drops with dry mopping may help resolve ear discharge at 3 to 4 months, compared with dry mopping alone, but we are very uncertain | ||

| 31.5% | 54.5% (38.1 to 77.9) | 23.0% more (6.6 more to 46.3 more) | |||||

| Health‐related quality of life ‐ not reported | — | — | — | — | — | — | No study reported this outcome |

| Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation ‐ not reported | — | — | — | — | — | — | No study reported this outcome |

| Hearing Follow‐up: 4 months | 180 (1 RCT) |

One study stated that "there was no deterioration of hearing in groups 2 [boric acid] ... as compared to group 1 [no additional treatment]." | very low2 | We are very uncertain whether hearing is improved when boric acid in alcohol is used with dry mopping | |||

| Serious complications ‐ not reported | — | — | — | — | — | — | No study reported that any participant died or had any intracranial or extracranial complications |

| Suspected ototoxicity | 180 (1 RCT) |

One study stated that "there was no deterioration of hearing in groups 2 [boric acid] ...as compared to group 1 [no additional treatment]. Thus, no signs of ototoxicity could be found." | very low3 | — | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||||

1Downgraded to very low‐certainty: downgraded by two levels due to study limitations (risk of bias) because of concerns about randomisation, blinding, attrition bias and selective reporting. Downgraded by one level due to imprecision as there was one small study (180 participants) with a confidence interval crossing the line of minimally important benefit.

2Downgraded to very low‐certainty: downgraded by two levels due to study limitations (risk of bias) because of concerns about randomisation, blinding, attrition bias and selective reporting. Downgraded by one level due to imprecision as numeric results were not presented for this outcome.

3Downgraded to very low‐certainty: downgraded by two levels due to study limitations (risk of bias) because of concerns about randomisation, blinding, attrition bias and selective reporting. Downgraded by one level due to indirectness of the outcome: only hearing appears to have been considered for the outcome of ototoxicity and not other factors such as tinnitus or balance problems. Downgraded by one level due to imprecision, as numeric results were not presented for this outcome.

Background

This is one of a suite of Cochrane Reviews evaluating the comparative effectiveness of non‐surgical interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media using topical antibiotics, topical antibiotics with corticosteroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antiseptics and aural toileting (ear cleaning) methods (Table 2).

1. Table of Cochrane Reviews.

| Topical antibiotics with steroids | Topical antibiotics | Systemic antibiotics | Topical antiseptics | Aural toileting (ear cleaning) | |

| Topical antibiotics with steroids | Review CSOM‐4 | ||||

| Topical antibiotics | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐1 | |||

| Systemic antibiotics | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐3 | Review CSOM‐2 | ||

| Topical antiseptics | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐6 | Review CSOM‐6 | Review CSOM‐5 | |

| Aural toileting | Review CSOM‐4 | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Review CSOM‐7 |

| Placebo (or no intervention) | Review CSOM‐4 | Review CSOM‐1 | Review CSOM‐2 | Review CSOM‐5 | Review CSOM‐7 |

CSOM‐1: Topical antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Brennan‐Jones 2018a).

CSOM‐2: Systemic antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Chong 2018a).

CSOM‐3: Topical versus systemic antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Chong 2018b).

CSOM‐4: Topical antibiotics with steroids for chronic suppurative otitis media (Brennan‐Jones 2018b).

CSOM‐5: Topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Head 2018a).

CSOM‐6: Antibiotics versus topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media (Head 2018b).

CSOM‐7: Aural toilet (ear cleaning) for chronic suppurative otitis media (Bhutta 2018).

This review compares the effectiveness of topical antiseptics (without corticosteroids) against other antiseptics or placebo/no treatment for chronic suppurative otitis media.

Description of the condition

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), which is also often referred to as chronic otitis media (COM), is a chronic inflammation and infection of the middle ear and mastoid cavity, characterised by ear discharge (otorrhoea) through a perforated tympanic membrane.

The predominant symptoms of CSOM are ear discharge and hearing loss. Ear discharge can be persistent or intermittent, and many sufferers find it socially embarrassing (Orji 2013). Some patients also experience discomfort or earache. Most patients with CSOM experience temporary or permanent hearing loss with average hearing levels typically between 10 and 40 decibels (Jensen 2013). The hearing loss can be disabling, and it can have an impact on speech and language skills, employment prospects, and on children’s psychosocial and cognitive development, including academic performance (Elemraid 2010; Olatoke 2008; WHO 2004). Consequently, quality of life can be affected. CSOM can also progress to serious complications in rare cases (and more often when cholesteatoma is present): both extracranial complications (such as mastoid abscess, postauricular fistula and facial palsy) and intracranial complications (such as otitic meningitis, lateral sinus thrombosis and cerebellar abscess) have been reported (Dubey 2007; Yorgancılar 2013).

CSOM is estimated to have a global incidence of 31 million episodes per year, or 4.8 new episodes per 1000 people (all ages), with 22% of cases affecting children under five years of age (Monasta 2012; Schilder 2016). The prevalence of CSOM varies widely between countries, but it disproportionately affects people at socio‐economic disadvantage. It is rare in high‐income countries, but common in many low‐ and middle‐income countries (Mahadevan 2012; Monasta 2012; Schilder 2016; WHO 2004).

Definition of disease

There is no universally accepted definition of CSOM. Some define CSOM in patients with a duration of otorrhoea of more than two weeks but others may consider this an insufficient duration, preferring a minimum duration of six weeks or more than three months (Verhoeff 2006). Some include diseases of the tympanic membrane within the definition of CSOM, such as tympanic perforation without a history of recent ear discharge, or the disease cholesteatoma (a growth of the squamous epithelium of the tympanic membrane).

In accordance with a consensus statement, here we use CSOM only to refer to tympanic membrane perforation, with intermittent or continuous ear discharge (Gates 2002). We have used a duration of otorrhoea of two weeks as an inclusion criterion, in accordance with the definition used by the World Health Organization, but we have used subgroup analyses to explore whether this is a factor that affects observed treatment effectiveness (WHO 2004).

Many people affected by CSOM do not have good access to modern primary healthcare, let alone specialised ear and hearing care, and in such settings health workers may be unable to view the tympanic membrane to definitively diagnose CSOM. It can also be difficult to view the tympanic membrane when the ear discharge is profuse. Therefore we have also included, as a subset for analysis, studies where participants have had chronic ear discharge for at least two weeks, but where the diagnosis is unknown.

At‐risk populations

Some populations are considered to be at high risk of CSOM. There is a high prevalence of disease among Indigenous people such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian, Native American and Inuit populations. This is likely due to an interplay of factors, including socio‐economic deprivation and possibly differences resulting from population genetics (Bhutta 2016). Those with primary or secondary immunodeficiency are also susceptible to CSOM. Children with craniofacial malformation (including cleft palate) or chromosomal mutations such as Down syndrome are prone to chronic non‐suppurative otitis media ('glue ear'), and by extrapolation may also be at greater risk of suppurative otitis media. The reasons for this association with craniofacial malformation are not well understood, but may include altered function of the Eustachian tube, coexistent immunodeficiency, or both. These populations may be less responsive to treatment and more likely to develop CSOM, recurrence or complications.

Children who have a grommet (ventilation tube) in the tympanic membrane to treat glue ear or recurrent acute otitis media may be more prone to develop CSOM; however, their pathway to CSOM may differ and therefore they may respond differently to treatment. Children with grommets who have chronic ear discharge meeting the CSOM criteria are therefore considered to be a separate high‐risk subgroup (van der Veen 2006).

Treatment

Treatments for CSOM may include topical antibiotics (administered into the ear) with or without steroids, systemic antibiotics (given either by mouth or by injection), topical antiseptics and ear cleaning (aural toileting), all of which can be used on their own or in various combinations. Whereas primary healthcare workers or patients themselves can deliver some treatments (for example, some aural toileting and antiseptic washouts), in most countries antibiotic therapy requires prescription by a doctor. Surgical interventions are an option in cases where complications arise or in patients who have not responded to pharmacological treatment; however, there is a range of practice in terms of the type of surgical intervention that should be considered and the timing of the intervention. In addition, access to or availability of surgical interventions is setting‐dependent. This series of Cochrane Reviews therefore focuses on non‐surgical interventions. In addition, most clinicians consider cholesteatoma to be a variant of CSOM, but acknowledge that it will not respond to non‐surgical treatment (or will only respond temporarily) (Bhutta 2011). Therefore, people with cholesteatoma are not included in these reviews.

Description of the intervention

Antiseptics are substances that kill or inhibit the growth and development of micro‐organisms. Agents that have been used for treating CSOM include povidone iodine, aluminium acetate, boric acid, alcohol, acetic acid and hydrogen peroxide. Antiseptics can be delivered as drops or as washes using a syringe. The frequency of administration and duration of treatment can vary. Syringing may bring additional benefit by flushing out debris or pus, thus reducing the overall bacterial load. Antiseptics can be used alone or in addition to other treatments for CSOM, such as antibiotics or aural toileting.

How the intervention might work

CSOM is a chronic and often polymicrobial (involving more than one micro‐organism) infection of the middle ear. Topical antiseptics are administered to the ear to inhibit the micro‐organisms that may be responsible for the condition. Although the mechanism of action of most antiseptics is thought to relate to disruption of the bacterial cell wall followed by penetration into the cell and action at the target site(s), different groups of antiseptics have different properties (e.g. iodines, alcohols, acids) (Table 3). We therefore analysed these groups separately and pooling only occurred where there was no evidence of a difference in effect.

2. Antiseptics that have been used to treat CSOM.

| Antiseptic agent used aurally | Target and mechanism of action |

| Rubbing alcohol (ethanol, isopropanol) | Penetrating agents that cause loss of cellular membrane function, leading to release of intracellular components, denaturing of proteins, and inhibition of DNA, RNA, protein and peptidoglycan synthesis. |

| Povidone iodine | Highly active oxidising agents that destroy cellular activity of proteins. Disrupts oxidative phosphorylation and membrane‐associated activities. Iodine reacts with cysteine and methionine thiol groups, nucleotides and fatty acids, resulting in cell death. |

| Chlorhexidine | Membrane‐active agents that damage cell wall and outer membrane, resulting in collapse of membrane potential and intracellular leakage. Enhanced passive diffusion mediates further uptake, causing coagulation of cytosol. |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Produces hydroxyl free radicals that function as oxidants, which react with lipids, proteins and DNA. Sulfhydryl groups and double bonds are targeted in particular, thus increasing cell permeability. |

| Boric acid | It is likely that the change in the pH media of the ear canal interrupts the growth of bacteria by affecting the amino acid, which causes alteration in the three‐dimensional structure of bacterial enzymes. Extreme changes in pH cause protein denaturation. |

| Aluminium acetate/acetic acid | Acetic acid changes the pH media of the ear canal and interrupts the growth of bacteria by affecting the amino acid, which causes alteration in the three‐dimensional structure of bacterial enzymes. Extreme changes in pH cause protein denaturation. Aluminium acetate is an astringent that helps reduce itching, stinging and inflammation. |

Sources: Gupta 2015; McDonnell 1999; Sheldon 2005.

Antiseptics or their application can cause physical, chemical or allergic irritation of the skin of the outer ear, manifesting as discomfort/pain or itching. Some antiseptics (such as chlorhexidine or alcohol) can be toxic to the inner ear (ototoxicity), so there is a risk of causing sensorineural hearing loss, dizziness or tinnitus.

Why it is important to do this review

Antiseptic agents generally cost less than some of the other treatments available for the treatment of CSOM (in particular topical antibiotics). They are also more readily available, do not require prescription by a doctor and do not need refrigerated transport, which makes them attractive for use in resource‐constrained environments. Evidence‐based knowledge of their effectiveness and the relative effectiveness of the different types of antiseptic could help to optimise their use.

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical antiseptics for people with chronic suppurative otitis media.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies with the following design characteristics:

Randomised controlled trials (including cluster‐randomised trials where the unit of randomisation is the setting or operator) and quasi‐randomised trials.

Patients were followed up for at least one week.

We excluded studies with the following design characteristics:

Cross‐over trials, because CSOM is not expected to be a stable chronic condition. Unless data from the first phase were available, we excluded such studies.

Types of participants

We included studies with patients (adults and children) who had:

chronic ear discharge of unknown cause; or

chronic suppurative otitis media.

We defined patients with chronic ear discharge as patients with at least two weeks of ear discharge, where the cause of the discharge was unknown.

We defined patients with chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) as patients with:

chronic or persistent ear discharge for at least two weeks; and

a perforated tympanic membrane.

We did not exclude any populations based on age, risk factors (cleft palate, Down syndrome), ethnicity (e.g. Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders) or the presence of ventilation tubes (grommets). Where available, we recorded these factors in the patient characteristics section during data extraction from the studies. If any of the included studies recruited these patients as a majority (80% or more), we analysed them in a subgroup analysis (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

We excluded studies where the majority (more than 50%) of participants:

had an alternative diagnosis to CSOM (e.g. otitis externa);

had underlying cholesteatoma;

had ear surgery within the last six weeks.

We did not include studies designed to evaluate interventions in the immediate peri‐surgical period, which were focused on assessing the impact of the intervention on the surgical procedure or outcomes.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Any single, or combination of, topical antiseptic agent of any class including but not limited to) povidone iodine, aluminium acetate, boric acid, alcohol and hydrogen peroxide. The topical antiseptics could be applied directly into the ear canal as ear drops, powders or irrigations, or as part of an aural toileting procedure.

Dose/duration

There was no limitation on the dose, duration or frequency of application.

Comparisons

The following were the comparators:

Placebo, no intervention (topical antiseptic versus placebo/no intervention).

Another topical antiseptic (topical antiseptic A versus topical antiseptic B).

There were two potential scenarios for analysis:

Topical antiseptics as a stand‐alone treatment: studies where all participants either received no treatment or only received aural toileting. This also included situations where the comparison group received a single administration of antiseptic (e.g. as part of microsuction at the start of treatment).

Topical antiseptics as an add‐on to topical/systemic antibiotics: studies where all participants received topical or systemic antibiotics, with or without aural toileting procedures.

Many comparison pairs were possible in this review. The main comparisons of interest that we have summarised and presented in the 'Summary of findings' table are:

topical antiseptics as a single therapy (main treatment) versus placebo/no intervention; and

topical antiseptics versus placebo/no intervention, where both arms also received topical or systemic antibiotics.

Types of outcome measures

We analysed the following outcomes in the review, but we did not use them as a basis for including or excluding studies.

We extracted and reported data from the longest available follow‐up for all outcomes.

Primary outcomes

-

Resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear' (whether otoscopically confirmed or not), measured at:

between one week and up to two weeks;

two weeks to up to four weeks; and

after four weeks.

Health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument for CSOM (e.g. Chronic Otitis Media Questionnaire (COMQ)‐12 (Phillips 2014a; Phillips 2014b; van Dinther 2015), Chronic Otitis Media Outcome Test (COMOT)‐15 (Baumann 2011), Chronic Ear Survey (CES) (Nadol 2000)).

Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation.

Secondary outcomes

Hearing, measured as the pure‐tone average of air conduction thresholds across four frequencies tested (500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz) of the affected ear. If this was not available, we reported the pure‐tone average of the thresholds measured.

Serious complications, including intracranial complications (such as otitic meningitis, lateral sinus thrombosis and cerebellar abscess) and extracranial complications (such as mastoid abscess, postauricular fistula and facial palsy), and death.

-

Ototoxicity; this was measured as 'suspected ototoxicity' as reported by the studies where available, and as the number of people with the following symptoms that may be suggestive of ototoxicity:

sensorineural hearing loss;

balance problems/dizziness/vertigo;

tinnitus.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane ENT Information Specialist conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. The date of the search was 1 April 2019.

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist searched:

the Cochrane ENT Register (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies to 1 April 2019);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4) (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies Web to1 April 2019);

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946 to 1 April 2019);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 1 April 2019);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 1 April 2019);

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database), lilacs.bvsalud.org (search to 1 April 2019);

Web of Knowledge, Web of Science (1945 to 1 April 2019);

ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov (search via the Cochrane Register of Studies to 1 April 2019);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (search to 1 April 2019).

We also searched:

IndMed (search to 22 March 2018);

African Index Medicus (search to 22 March 2018).

The search strategies for major databases are detailed in Appendix 1. The Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. The strategies were designed to identify all relevant studies for a suite of reviews on various interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media (Bhutta 2018; Brennan‐Jones 2018a; Brennan‐Jones 2018b; Chong 2018a; Chong 2018b; Head 2018a; Head 2018b). Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2011).

Searching other resources

We scanned the reference lists of identified publications for additional trials and contacted trial authors where necessary. In addition, the Information Specialist searched Ovid MEDLINE to retrieve existing systematic reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. The Information Specialist also ran non‐systematic searches of Google Scholar to retrieve grey literature and other sources of potential trials.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects. We considered adverse effects as described in the included studies only.

We contacted original authors for clarification and further data if trial reports were unclear and we arranged translations of papers where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two review authors (KH/LYC) independently screened all titles and abstracts of the references obtained from the database searches to identify potentially relevant studies. At least two review authors (KH/LYC) evaluated the full text of each potentially relevant study to determine whether it met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review.

We resolved any differences by discussion and consensus, with the involvement of a third author for clinical and methodological input where necessary.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors (KH/LYC/CBJ/MB) independently extracted data from each study using a standardised data collection form (see Appendix 2). Whenever a study had more than one publication, we retrieved all publications to ensure complete extraction of data. Where there were discrepancies in the data extracted by different review authors, we checked these against the original reports and resolved any differences by discussion and consensus, with the involvement of a third author or a methodologist where appropriate. We contacted the original study authors for clarification or for missing data whenever possible. If differences were found between publications of a study, we contacted the original authors for clarification. We used data from the main paper(s) if no further information was found.

We included key characteristics of the included studies, such as study design, setting (including location), year of study, sample size, age and sex of participants, and how outcomes were defined or collected in the studies. In addition, we also collected baseline information on prognostic factors or effect modifiers (see Appendix 2). For this review, this included the following information whenever available:

duration of ear discharge at entry to the study;

diagnosis of ear discharge (where known);

number people who may have been at higher risk of CSOM, including those with cleft palate or Down syndrome;

ethnicity of participants including the number who were from Indigenous populations;

number who had previously had ventilation tubes (grommets) inserted (and, where known, the number who had tubes still in place);

number who had previous ear surgery;

number who had previous treatments for CSOM (non‐responders, recurrent versus new cases).

We recorded concurrent treatments alongside the details of the interventions used. See the 'Data extraction form' in Appendix 2 for more details.

For the outcomes of interest to the review, we extracted the findings of the studies on an available case analysis basis, i.e. we included data from all patients available at the time points based on the treatment randomised whenever possible, irrespective of compliance or whether patients had received the treatment as planned.

In addition to extracting pre‐specified information about study characteristics and aspects of methodology relevant to risk of bias, we extracted the following summary statistics for each trial and each outcome:

For continuous data: the mean values, standard deviations and number of patients for each treatment group. Where endpoint data were not available, we extracted the values for change from baseline. We analysed data from disease‐specific quality of life scales such as COMQ‐12, COMOT‐15 and CES as continuous data.

For binary data: the number of participants who experienced an event and the number of patients assessed at the time point.

For ordinal scale data: if the data appeared to be approximately normally distributed or if the analysis that the investigators performed suggested parametric tests were appropriate, then we treated the outcome measures as continuous data. Alternatively, if data were available, we converted it into binary data.

Time‐to‐event outcomes: we did not expect any outcomes to be measured as time‐to‐event data. However, if outcomes such as resolution of ear discharge were measured in this way, we reported the hazard ratios.

For resolution of ear discharge, we extracted the longest available data within the time frame of interest, defined as from one week up to (and including) two weeks (7 days to 14 days), from two weeks up to (and including) four weeks (15 to 28 days), and after four weeks (28 days or one month).

For other outcomes, we reported the results from the longest available follow‐up period.

Extracting data for pain/discomfort and adverse effects

For these outcomes, there were variations in how studies had reported the outcomes. For example, some studies reported both 'pain' and 'discomfort' separately whereas others did not. Prior to the commencement of data extraction, we agreed and specified a data extraction algorithm for how data should be extracted.

We extracted data for serious complications as a composite outcome. If a study reported more than one complication and we could not distinguish whether these occurred in one or more patients, we extracted the data with the highest incidence to prevent double counting.

Extracting data from figures

Where values for primary or secondary outcomes were shown as figures within the paper, we attempted to contact the study authors to try to obtain the raw values. When the raw values were not provided, we extracted information from the graphs using an online data extraction tool, using the best quality version of the relevant figures available.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors (KH/LYC/CBJ/MB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study. We followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011), using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. With this tool we assessed the risk of bias as 'low', 'high' or 'unclear' for each of the following six domains:

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting;

other sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We summarised the effects of dichotomous outcomes (e.g. proportion of patients with complete resolution of ear discharge) as risk ratios (RR) with confidence intervals (CIs). For the key outcomes that are presented in the 'Summary of findings' table, we expressed the results as absolute numbers based on the pooled results and compared to the assumed risk. We also calculated the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) using the pooled results. The assumed baseline risk was typically either (a) the median of the risks of the control groups in the included studies, this being used to represent a 'medium‐risk population' or, alternatively, (b) the average risk of the control groups in the included studies, which is used as the 'study population' (Handbook 2011). If a large number of studies were available, and where appropriate, we also attempted to present additional data based on the assumed baseline risk in (c) a low‐risk population and (d) a high‐risk population.

For continuous outcomes, we expressed treatment effects as a mean difference (MD) with standard deviation (SD). If different scales were used to measure the same outcome, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) and provided a clinical interpretation of the SMD values.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over studies

This review did not use data from phase II of cross‐over studies.

The ear as the unit of randomisation: within‐patient randomisation in patients with bilateral ear disease

For data from studies where 'within‐patient' randomisation was used (i.e. studies where both ears (right versus left) were randomised) we adjusted the analyses for the paired nature of the data (Elbourne 2002; Stedman 2011), as outlined in section 16.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011).

The ear as the unit of randomisation: non‐paired randomisation in patients with bilateral ear disease

Some patients with bilateral disease may have received the same treatment in both ears, whereas others received a different treatment in each ear. We did not exclude these studies, but we only reported the data if specific pairwise adjustments were completed or if sufficient data were obtained to be able to make the adjustments.

The patient as the unit of randomisation

Some studies randomise by patient and those with bilateral CSOM received the same intervention for both ears. In some studies the results may be reported as a separate outcome for each ear (the total number of ears is used as the denominator in the analysis). The correlation of response between the left ear and right ear when given the same treatment was expected to be very high, and if both ears were counted in the analysis this was effectively a form of double counting, which may be especially problematic in smaller studies if the number of people with bilateral CSOM was unequal. We did not exclude these studies, but we only reported the results if the paper presented the data in such a way that we could include the data from each participant only once (one data point per participant) or if we had enough information to reliably estimate the effective sample size or inflated standard errors as presented in chapter 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011). If this was not possible, we attempted to contact the authors for more information. If there was no response from the authors, then we did not include data from these studies in the analysis.

If we found cluster‐randomised trials by setting or operator, we analysed these according to the methods in section 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the study authors via email whenever the outcome of interest was not reported but the methods of the study had suggested that the outcome had been measured. We did the same if not all of the data required for the meta‐analysis was reported, unless the missing data were standard deviations. If standard deviation data was not available, we approximated these using the standard estimation methods from P values, standard errors or 95% CIs if these were reported, as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011). Where it was impossible to estimate these, we contacted the study authors.

Apart from imputations for missing standard deviations, we did not conduct any other imputations. We extracted and analysed data for all outcomes using the available case analysis method.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity (which may be present even in the absence of statistical heterogeneity) by examining the included studies for potential differences in the types of participants recruited, interventions or controls used, and the outcomes measured. We did not pool studies where the clinical heterogeneity made it unreasonable to do so.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plots and by considering the Chi² test (with a significance level set at P value < 0.10) and the I² statistic, which calculates the percentage of variability that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, with I² values over 50% suggesting substantial heterogeneity (Handbook 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias as within‐study outcome reporting bias and between‐study publication bias.

Outcome reporting bias (within‐study reporting bias)

We assessed within‐study reporting bias by comparing the outcomes reported in the published report against the study protocol, whenever this could be obtained. If the protocol was not available, we compared the outcomes reported to those listed in the methods section. If results were mentioned but not reported adequately in a way that allowed analysis (e.g. the report only mentioned whether the results were statistically significant or not), bias in a meta‐analysis was likely to occur. We tried to find further information from the study authors, but if no further information could be obtained, we noted this as being a high risk of bias. Where there was insufficient information to judge the risk of bias, we noted this as an unclear risk of bias (Handbook 2011).

Publication bias (between‐study reporting bias)

We intended to create funnel plots if sufficient studies (more than 10) were available for an outcome. If we observed asymmetry of the funnel plot, we would have conducted a more formal investigation using the methods proposed by Egger 1997.

Data synthesis

We conducted all meta‐analyses using Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014). For dichotomous data, we analysed treatment differences as a risk ratio (RR) calculated using the Mantel‐Haenszel methods. We analysed time‐to‐event data using the generic inverse variance method.

For continuous outcomes, if all the data was from the same scale, we pooled the mean values obtained at follow‐up with change outcomes and reported this as a MD. However, if the SMD had to be used as an effect measurement, we did not pool change and endpoint data.

When statistical heterogeneity is low, random‐effects versus fixed‐effect methods yield trivial differences in treatment effects. However, when statistical heterogeneity is high, the random‐effects method provides a more conservative estimate of the difference.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We subgrouped studies where most participants (80% or more) met the criteria stated below in order to determine whether the effect of the intervention was different compared to other patients. Due to the risks of reporting and publication bias with unplanned subgroup analyses of trials, we only analysed subgroups reported in studies if these were prespecified and stratified at randomisation.

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses regardless of whether statistical heterogeneity was observed for studies that included patients identified as high‐risk (i.e. thought to be less responsive to treatment and more likely to develop CSOM, recurrence or complications) and patients with ventilation tubes (grommets). 'High‐risk' patients include Indigenous populations (e.g. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Native Americans and Inuit populations of Alaska, Canada and Greenland), people with craniofacial malformation (e.g. cleft palate), Down syndrome and people with known immunodeficiency.

We planned to present the main analyses of this review in the form of forest plots based on this main subgroup analysis.

For the high‐risk group, this applied to the outcomes resolution of ear discharge (dry ear), quality of life, pain/discomfort, development of complications and hearing loss.

For patients with ventilation tubes, this applied to the outcome resolution of ear discharge (dry ear) for the time point of four weeks or more because this group was perceived to be at lower risk of treatment failure and recurrence than other patient groups. If statistical heterogeneity was observed, we also conducted subgroup analysis for the effect modifiers below. If there were statistically significant subgroup effects, we presented these subgroup analysis results as forest plots.

For this review, effect modifiers included:

Diagnosis of CSOM: it was likely that some studies would include patients with chronic ear discharge but who had not had a diagnosis of CSOM. Therefore, we subgrouped studies where most patients (80% or more) met the criteria for CSOM diagnosis in order to determine whether the effect of the intervention was different compared to patients where the precise diagnosis was unknown and inclusion into the study was based purely on chronic ear discharge symptoms.

Duration of ear discharge: there is uncertainty about whether the duration of ear discharge prior to treatment has an impact on the effectiveness of treatment and whether more established disease (i.e. discharge for more than six weeks) is more refractory to treatment compared with discharge of a shorter duration (i.e. less than six weeks).

Patient age: patients who were younger than two years old versus patients up to six years old versus adults. Patients under two years are widely considered to be more difficult to treat.

We presented the results as subgroups regardless of the presence of statistical heterogeneity based on the type of antiseptics (e.g. iodines, alcohols, acids). This was because different types of antiseptics have different mechanisms of action and therefore the treatment effects and adverse effect profiles were likely to be different.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to determine whether the findings were robust to the decisions made in the course of identifying, screening and analysing the trials. We planned to conduct sensitivity analysis for the following factors, whenever possible:

Impact of model chosen: fixed‐effect versus random‐effects model.

Risk of bias of included studies: excluding studies with high risk of bias (we defined these as studies that have a high risk of allocation concealment bias and a high risk of attrition bias (overall loss to follow‐up of 20%, differential follow‐up observed)).

Where there was statistical heterogeneity, studies that only recruited patients who had previously not responded to one of the treatments under investigation in the RCT. Studies that specifically recruited patients who did not respond to a treatment could potentially have reduced the relative effectiveness of an agent.

If any of these investigations found a difference in the size of the effect or heterogeneity, we mentioned this in the Effects of interventions section and/or presented the findings in a table.

GRADE and 'Summary of findings' table

Using the GRADE approach, at least two review authors (KH/LYC) independently rated the overall certainty of evidence using the GDT tool (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/) for the main comparison pairs listed in the Types of interventions section. The certainty of evidence reflects the extent to which we are confident that an estimate of effect is correct and we applied this in the interpretation of results. There were four possible ratings: 'high', 'moderate', 'low' and 'very low' (Handbook 2011). A rating of 'high' certainty evidence implies that we are confident in our estimate of effect and that further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. A rating of 'very low' certainty implies that any estimate of effect obtained is very uncertain.

The GRADE approach rates evidence from RCTs that do not have serious limitations as high certainty. However, several factors could lead to the downgrading of the evidence to moderate, low or very low. The degree of downgrading is determined by the seriousness of these factors:

study limitations (risk of bias);

inconsistency;

indirectness of evidence;

imprecision;

publication bias.

The 'Summary of findings' table presents the following outcomes:

-

resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear':

at between one week and up to two weeks;

after four weeks;

health‐related quality of life;

ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation;

hearing;

serious complications;

suspected ototoxicity.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

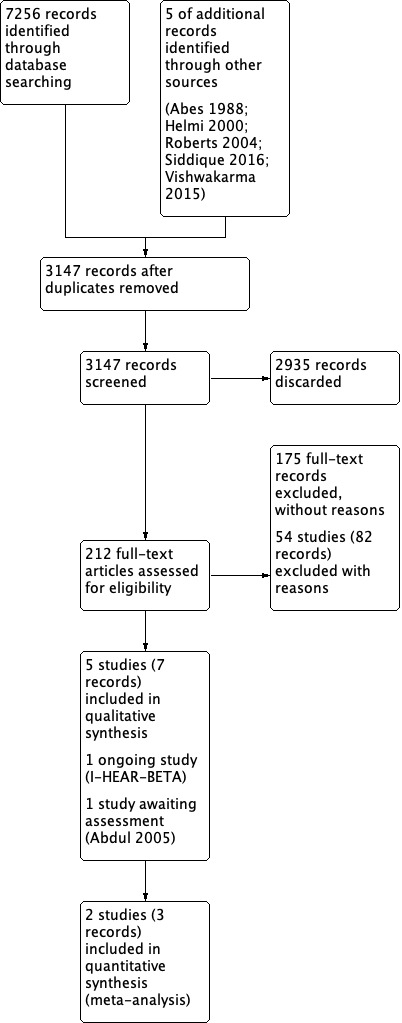

The searches retrieved a total of 7256 references and we identified five additional references from other sources. This reduced to 3147 after removal of duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts and subsequently removed 2935 references. We assessed 212 full texts for eligibility of which we excluded 203 references; we excluded 82 of these references (54 studies) with reasons recorded in the review (see Excluded studies).

We included seven references (five studies). We identified one ongoing study (I‐HEAR‐BETAa; see Characteristics of ongoing studies) and there is one reference awaiting classification (Abdul 2005; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

A flow chart of study retrieval and selection is provided in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Five studies were included (Eason 1986; Loock 2012; Minja 2006; Papastavros 1989; Van Hasselt 1998b). Table 4 and the Characteristics of included studies table provide a summary of the included studies.

3. Summary of study characteristics.

|

Ref ID (no. participants) |

Setting | Population | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Treatment duration | Follow‐up | Background Treatment | Notes |

| Topical antiseptics versus placebo/no treatment | ||||||||

|

Minja 2006 (n = 254 people) |

Tanzania, Schools (community) |

Children with CSOM for more than 3 months Mean age 11.8 years |

Boric acid in alcohol ear drops No further information |

No treatment | 1 month | 3 to 4 months | Daily aural toilet (dry mopping) | Cluster‐randomised trial by school Part of a 3‐arm trial |

|

Eason 1986 (n = 43 people) |

Solomon Islands, villages (community) | Children with CSOM for more than 3 months Mean age 5.4 years |

2% boric acid in 20% alcohol 3 ear drops/6 hours |

No treatment | Up to 6 weeks | 4 to 6 weeks | Daily aural toilet (dry mopping) | Part of a 5‐arm trial |

|

Van Hasselt 1998b (n = ? people, 174 ears) |

Malawi, villages (community) |

"CSOM" (no further definition) No age information |

1% povidone Iodine in 1.5% hypromellose (HPMC) – single application | HPMC alone | Single application | 1 week | Suction cleaning before application | Unpublished study Part of 3‐arm trial |

| Topical antiseptic A versus topical antiseptics B | ||||||||

|

Loock 2012 (n = 106 people) |

South Africa, City (secondary care) | Patients with otorrhoea because of active mucosal COM Age over 6 years (90% between 20 and 34 years) |

1% acetic acid 6 drops/12 hours |

Boric acid powder Single administration |

4 weeks (except for boric acid) | Up to 8 weeks | Aural cleaning at 1st visit | Part of a 3‐arm trial |

|

Papastavros 1989 (n = ?, 48 ears) |

Greece, city (secondary care) |

Patients with discharging ears 11 to 79 years |

Hydrogen peroxide, no further information | Borax powder insufflation, no further information | 10 days | 10 days | None | — |

Study design and sample size

Four studies were three‐arm trials (Loock 2012; Minja 2006; Papastavros 1989; Van Hasselt 1998b), and one study was part of a five‐arm trial (Eason 1986). In all cases only two study arms were relevant to this review. Details of the other study arms can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

All studies provided an indication that they were 'randomised'. Four were parallel‐group studies (Eason 1986; Loock 2012; Papastavros 1989; Van Hasselt 1998b). Minja 2006, indicates in the abstract that it was a randomised controlled trial but describes in the methods that "All children with CSOM attending the same school were included in the same treatment group" indicating that it was probably a cluster‐randomised trial.

Sample size

The sample size from the studies was difficult to interpret as some studies reported the number of participants and some only reported the number of ears included (Table 4).

Unit of randomisation

The unit of randomisation for each study is presented in Table 5. Minja 2006 states that children attending the same school were in the same treatment group and that there were 24 schools included in the study (although the number of children at each school is not provided). In order to adjust the results for intra‐cluster correlation we have re‐calculated the results to with a intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.015 (see Unit of analysis issues for more details). No estimates from the literature were available for this population, but in general for cluster‐randomised trials the ICC is between 0.01 and 0.02. We carried out sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of the ICC.

4. Resolution of ear discharge outcome.

| Reference | Unit of randomisation | Reported | Definition | Otoscopically confirmed? | Time points | mNotes |

| Eason 1986 | Person | Results reported by ear | "dry" or "not discharging" | Unclear | 2 to 4 weeks: 3 weeks 4+ weeks: 6 weeks |

Results not used as it was not possible to account for correlation between ears due to bilateral disease. |

| Loock 2012 | Person | Results reported by person | "inactive" ear (dry) | Otoscopically confirmed | 2 to 4 weeks: 4 weeks | Also measured patient satisfaction which asked patients whether their ears were 'completely dry', 'better but not completely dry', 'no better, still running' |

| Minja 2006 | School | Results reported by person. Only considered 'dry' if both ears were dry. | "Dry" ear | Otoscopically confirmed | 2 to 4 weeks: 4 weeks 4+ weeks: 3 to 4 months |

Intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.015 was used |

| Papastavros 1989 | Ear | Results reported by ear | "cure" ‐ co‐existence of all 3 of the following conditions: 1. Ear free of discharge 2. Colour of mucosa: light pink 3. Absence of mucosal oedema, granulations or polyps |

Unclear ‐ but probably | 1 to 2 weeks: 10 days | Results not used as it was not possible to account for correlation between ears due to bilateral disease |

| Van Hasselt 1998b | Unclear | Results reported by ear | 'dry ear' | Unclear | 1 to 2 weeks: 1 week | Results not used as it was not possible to account for correlation between ears due to bilateral disease |

Location

Three studies were conducted in different countries in Africa: South Africa (Loock 2012), Tanzania (Minja 2006) and Malawi (Van Hasselt 1998b). The remaining two studies were conducted in Greece (Papastavros 1989) and the Solomon Islands (Eason 1986).

Settings of trials

Three studies were community studies taking place in villages (Eason 1986; Van Hasselt 1998b) or primary schools (Minja 2006) in rural locations. The remaining two studies were based in secondary care from the ENT departments of hospitals in cities (Loock 2012; Papastavros 1989). The years in which the studies were conducted were not well reported: two studies were published in the 1980s (Eason 1986; Papastavros 1989), one unpublished study was probably conducted in the 1990s (Van Hasselt 1998b), and the last two were published post 2000 (Loock 2012; Minja 2006)

Population

Age and sex

The unpublished study did not provide any patient characteristics (Van Hasselt 1998b).

The ages of participants are reported in Table 4. Four studies reported that they included both males and females. The percentage of females in studies ranged from 36.6% to 55.3%.

High‐risk populations

Eason 1986 recruited participants from the Solomon Islands, which we considered to be a 'high‐risk' Indigenous group. The paper stated that the incidence of CSOM in the population was 3.8% for under 15‐year olds. None of the other studies reported the inclusion of any of the 'high‐risk' populations as defined in our inclusion criteria (cleft palate, Down syndrome, Indigenous groups, immunocompromised patients).

Diagnosis (confirmed tympanic membrane perforation/presence of micro‐purulent discharge)

Four of the studies included patients with CSOM (Eason 1986; Loock 2012; Minja 2006; Van Hasselt 1998b), although the definition was not clear in the unpublished study Van Hasselt 1998b.

Papastavros 1989 included patients with "discharging ears" where the discharge was either persistent for previous six months or those who had a history of at least three recurrences in the last 12 months. The alternative diagnoses for the ear discharge were not well described although it is mentioned that, of the 65 participants that subsequently underwent surgery, a diagnosis of cholesteatoma and/or osteitis was made in 28 participants (43%).

Duration of ear discharge

Two studies required participants to have had ear discharge for at least three months before starting the study (Eason 1986; Minja 2006). Papastavros 1989 required patients to either have had persistent ear discharge for six months or at least three recurrences in the last 12 months. The paper does not report the number of patients falling into each of these categories or the average duration of discharge for participants at the start of the trial.

Two studies did not have inclusion criteria or provide details of the average duration of ear discharge at the start of the study (Loock 2012; Van Hasselt 1998b)

Other important effect modifiers

Ventilation tubes

Loock 2012 excluded patients with ventilation tubes. No other studies reported whether any participants had previous or current ventilation tubes.

Previous ear surgery

Papastavros 1989 reported that 68 participants (75%) had undergone previous surgery but this did not occur within six weeks of starting the trial. Loock 2012 excluded patients who had previous surgery and this was not recorded in any of the other studies.

Interventions

Details of the interventions, background treatments and treatment durations for each of the included studies are summarised in Table 4.

Comparisons

Three studies compared the use of topical antiseptics with no treatment:

Minja 2006: boric acid in alcohol drops + dry mopping versus dry mopping alone.

Eason 1986: boric acid in alcohol drops + dry mopping versus dry mopping alone.

Van Hasselt 1998b: povidone Iodine + hydroxypropyl methyl‐cellulose (HPMC) versus HPMC alone.

Two studies compared two different topical antiseptics and these were analysed as separate comparisons due to the different antiseptic agents used:

Loock 2012: acetic acid ear drops versus boric acid powder.

Papastavros 1989: hydrogen peroxide ear drops versus boric acid powder.

Outcomes

Resolution of ear discharge

All five studies reported resolution of ear discharge as an outcome, although the definitions, methods and timing of assessment differed between studies. These are summarised in Table 5.

Health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument

No studies measured this outcome.

Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation

Loock 2012 gave the number of participants who reported unpleasant taste and burning sensation. No other studies reported the outcome.

Hearing

The methods for two studies indicated that hearing was measured (Loock 2012; Minja 2006). The results for Loock 2012 were presented as a narrative and Minja 2006 did not present the results by treatment group.

Serious complications (including intracranial complications, extracranial complications and death)

Serious complications were not consistently reported. One study reported that no serious complications occurred (Loock 2012) and the other studies did not report the outcome.

Suspected ototoxicity

This outcome was not consistently reported; only one study mentioned ototoxicity as an outcome with no cases identified (Minja 2006).

Excluded studies

We excluded 54 studies (82 records) after reviewing the full text. Further details for the reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The main reasons for exclusion were as follows:

We excluded 50 studies (78 records) as the comparisons were not appropriate for this review, but were relevant to another review in this suite:

Topical antibiotics (CSOM‐1): Asmatullah 2014; de Miguel 1999; Esposito 1990; Fradis 1997; Gyde 1978; Jamallulah 2016; Kasemsuwan 1997; Kaygusuz 2002; Liu 2003; Mira 1993; Nawasreh 2001; Ramos 2003; Siddique 2016; Tutkun 1995; van Hasselt 1998a.

Systemic antibiotics (CSOM‐2): de Miguel 1999; Eason 1986; Esposito 1990; Fliss 1990; Ghosh 2012; Legent 1994; Nwokoye 2015; Onali 2018; Picozzi 1983; Ramos 2003; Renuknanada 2014; Rotimi 1990; Sanchez Gonzales 2001; Somekh 2000; van der Veen 2007.

Topical versus systemic antibiotics (CSOM‐3): de Miguel 1999; Esposito 1990; Esposito 1992; Povedano 1995; Ramos 2003; Yuen 1994.

Topical antibiotics with steroids (CSOM‐4): Boesorire 2000; Browning 1988; Couzos 2003; Crowther 1991; Eason 1986; Gendeh 2001; Helmi 2000; Indudharan 2005; Kaygusuz 2002; Lazo Saenz 1999; Leach 2008; Miro 2000; Panchasara 2015; Ramos 2003; Subramaniam 2001; Tong 1996.

Antibiotics versus topical antiseptics (CSOM‐6): Fradis 1997; Gupta 2015; Jaya 2003; Macfadyen 2005; van Hasselt 1997; Vishwakarma 2015.

Aural toileting (CSOM‐7): Eason 1986; Kiris 1998; Smith 1996.

We excluded the remaining four studies (four records) for the following reasons:

Browning 1983: the comparison was antibiotics compared with topical antiseptics.

Clayton 1990: less than 20% of participants within the study had CSOM.

Roydhouse 1981: the intervention was a mucolytic agent (bromhexine), which was not classified as an antiseptic.

Thorpe 2000: compared three concentrations of the same topical antiseptic (aluminium acetate), which is not a question included in this review.

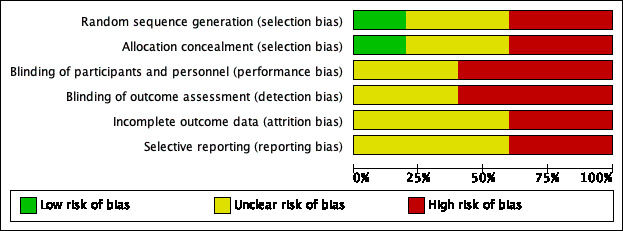

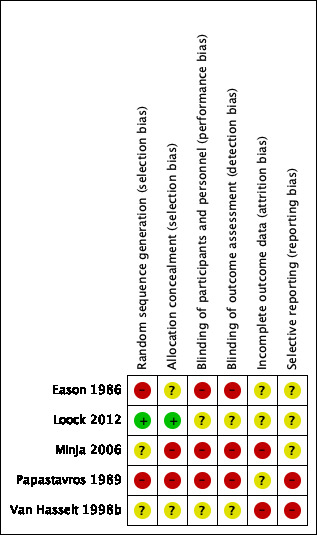

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 for the 'Risk of bias' graph (our judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies) and Figure 3 for the 'Risk of bias' summary (our judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

We judged two studies to be at high risk of selection bias with regards to randomisation. Papastavros 1989 did not provide details of how the randomisation schedule was produced and there were concerns about how patients were randomised. The paper reported that six participants were deliberately allocated to the systemic antibiotic group because they were suffering from more serious disease. Similarly, Eason 1986 did not provide information about sequence generation and there were unexplained imbalances between the groups. There were 1.6 times as many participants in the largest group compared to the smallest group, with the larger number of participants in the more effective treatment groups.

We assessed Minja 2006 and Van Hasselt 1998b as at 'unclear risk' because they did not provide enough information. We judged Loock 2012 to be at low risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

We assessed two studies to be at high risk of allocation concealment bias. Papastavros 1989 did not provide information regarding the method of allocation concealment but as the paper stated that six more severely affected participants were allocated to a specific treatment group it must be assumed that the allocation of participants to treatment groups was not well concealed. Minja 2006 indicated that the study was randomised but that participants from the same school were allocated to the same treatment group (i.e. a cluster‐randomised trial); it is not clear whether the people completing the allocation of schools knew to which group each school was going to be allocated.

Two studies did not provide enough information with regards to allocation concealment and so we assessed them as at unclear risk (Eason 1986; Van Hasselt 1998b). The remaining study was well reported and was at low risk (Loock 2012).

Blinding

Performance bias

We assessed three studies as high risk for performance bias due to a lack of blinding of participants and healthcare practitioners (Eason 1986; Minja 2006; Papastavros 1989).

We assessed two studies to be at unclear risk of performance bias. Loock 2012 made some attempts at blinding through the use of identical and unlabelled bottles, however one of the groups used a powder and the other used acetic acid ear drops, which have a characteristic smell, so it is likely that participants will have known to which group they were allocated. Van Hasselt 1998b indicated it was "double blinded" but as one of the treatments was iodine, these would have been different to the other solutions and so the effectiveness of blinding is not clear.

Detection bias

Similar to performance bias, we considered Eason 1986, Minja 2006 and Papastavros 1989 to be at high risk of bias due to the lack of blinding of outcome assessors, whereas Loock 2012 and Van Hasselt 1998b were at unclear risk as some attempts at blinding were made but there were doubts that these would have been successful.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed two studies to be at high risk of attrition bias (Minja 2006; Van Hasselt 1998b). Minja 2006 noted a loss to follow‐up that was both high and uneven across the groups: 23% (17/74) in the group with amoxicillin (systemic antibiotics), 19% (25/130) in the group with boric acid ear drops and 11% (14/124) in the group with only dry mopping. The reasons for dropout were not well evaluated. Van Hasselt 1998b did not provide information regarding the number of people starting the trial so it is not possible to determine whether there was a dropout rate during the trial and whether that could have impacted the results.

We considered three studies to be at unclear risk of attrition bias (Eason 1986; Loock 2012; Papastavros 1989). Two studies did not provide information about any patients who were lost to follow‐up (Eason 1986; Papastavros 1989). Loock 2012 provided the loss to follow‐up rates in the three treatment groups as 5.8%, 15.1% and 18.5% but did not provide reasons within the paper.

Selective reporting

We assessed Papastavros 1989 and Van Hasselt 1998b to be at high risk of selective reporting bias. Papastavros 1989 described several important criteria and assumptions for the measurement of success/failures in the methods section, but no information was provided in the results section. In addition, not all criteria for responses to treatment were fully reported, i.e. recurrence. For Van Hasselt 1998b, the study was not published and was only reported as a conference presentation that we were not able to access. The information comes from a paragraph in the introduction of a separate paper and so it is not possible to evaluate the methods fully due to lack of information presented.

The remaining three studies were at unclear risk of selective reporting bias (Eason 1986; Loock 2012; Minja 2006). The main issue with Loock 2012 and Minja 2006 was the poor reporting of the audiometry results. The level of reporting in Eason 1986 was very low and the definition of "improved" for the primary outcome was not provided.

None of the studies had protocols identified through searches of clinical trials registries.

Other potential sources of bias

Funding

Three studies were sponsored through national research grants (Eason 1986: Medical Research Council of New Zealand; Loock 2012: ENT society of South Africa, National Health Laboratory Service of South Africa; Minja 2006: SAREC a department of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) with Loock 2012 adding that "… the investigator received no sponsorship or incentive from manufacturers of any of the treatments used."

No information was provided in Papastavros 1989 or Van Hasselt 1998b.

Declarations of interest

Loock 2012 explicitly stated that "There was no conflict of interest …", whereas the remaining studies did not provide any information about conflicts of interest (Eason 1986; Minja 2006; Papastavros 1989; Van Hasselt 1998b).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: Topical antiseptics versus placebo/no treatment

Three studies were included in this comparison:

Eason 1986 (43 children; 58 ears) compared boric acid in alcohol drops plus aural toileting with aural toileting alone.

Minja 2006 (254 children) compared boric acid in alcohol plus aural toileting with aural toileting alone.

Van Hasselt 1998b (unclear number of people, 174 ears) compared a single application of povidone iodine in hydroxypropyl methyl‐cellulose (HPMC) versus HMPC alone.

See also Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear'

Although results were reported at one week by Van Hasselt 1998b, and at three and six weeks by Eason 1986, all of these results were presented by ear rather than by person. It is not possible to determine how many people with bilateral and unilateral disease were included and therefore it is not possible to account for the within‐person correlation between ears. These results could not be included in the analyses.

Between one week and up to two weeks

No studies reported the results per person for this outcome at between one week and up to two weeks.

Two weeks to up to four weeks

Minja 2006 identified that more participants in the group receiving topical antiseptics had dry ear compared to the no topical antiseptics group at four weeks (risk ratio (RR) 1.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20 to 3.16; 1 study; 174 participants) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Topical antiseptics versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Resolution of ear discharge (2 to 4 weeks).

After four weeks

Minja 2006 identified that more participants in the group receiving topical antiseptics had dry ear compared to the no topical antiseptics group at three to four months where the treatment duration was one month (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.47; 1 study; 180 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1).

Sensitivity analysis

As Minja 2006 appeared to be a cluster‐randomised controlled trial we adjusted the results using an intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.015 to account for the possible correlation of results within groups. We conducted a sensitivity analysis based on the ICC used and the results are available for two to four weeks in Analysis 2.1 and at three to four months in Analysis 2.2. The sensitivity analysis indicates that the choice of ICC does not influence the overall results greatly.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: topical antiseptics versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Resolution of ear discharge (2 to 4 weeks).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: topical antiseptics versus no treatment, Outcome 2 Resolution of ear discharge (3 to 4 months).

Health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Hearing

Minja 2006 measured hearing but presented the numeric results according to the outcome of the ear and so it was not possible to use the results. However, the authors stated that "there was no deterioration of hearing in groups 2 [boric acid] ... as compared to group 1 [no additional treatment]" (very low‐certainty evidence).

Serious complications (including intracranial complications, extracranial complications and death)

No studies reported that any participant died or had any intracranial or extracranial complications.

Suspected ototoxicity

Minja 2006 stated that "there was no deterioration of hearing in groups 2 [boric acid] and 3 [systemic antibiotic PLUS boric acid], as compared to group 1 [no additional treatment]. Thus, no signs of ototoxicity could be found" (very low‐certainty evidence).

Subgroup analysis

Although we had planned to complete subgroup analyses, as only one study was included in the qualitative analysis these were not possible.

Comparison 2: Boric acid powder versus acetic acid ear drops

One study (106 participants) compared a single instillation of boric acid powder with daily instillation of acetic acid ear drops for four weeks (Loock 2012).

Primary outcomes

Resolution of ear discharge or 'dry ear'

Between one week and up to two weeks

The study did not present results for this outcome.

Two weeks to up to four weeks

Loock 2012 (93 participants) found that the use of boric acid powder may result in more dry ears at four weeks compared to the use of acetic acid ear drops (RR 2.61, 95% CI 1.51 to 4.53) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Topical antibiotic A versus topical antibiotic B, Outcome 1 Resolution of ear discharge (2 to 4 weeks).

After four weeks

Loock 2012 provided results for those ears that were 'dry' at the four‐week follow‐up, but not for all randomised participants.

Health‐related quality of life using a validated instrument

The study did not measure this outcome.

Ear pain (otalgia) or discomfort or local irritation

Loock 2012 reported four cases of unpleasant taste and burning sensation with acetic acid but did not report any pain, discomfort or local irritation with boric acid powder (RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.81; 93 participants) (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Topical antibiotic A versus topical antibiotic B, Outcome 2 Ear pain, discomfort, irritation.

Secondary outcomes

Hearing

Loock 2012 measured hearing but only reported the results qualitatively in the paper, commenting "Audiometric tests showed no detectable overall, isolated nor idiosyncratic hearing loss from any treatment".