To the Editor:

Many patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) lose capacity during their hospitalization and require a friend or family member to act as a surrogate decision maker (1). Communicating about prognosis with these surrogates can be challenging. Although surrogates vary in how they prefer to hear prognostic information, most value communication that conveys compassion, empathy, and respect (2–4) and avoids “medical speak” (5). In this study, we characterized how intensivists responded when a surrogate family member explicitly asked about prognosis for survival in a high-fidelity simulation. Results of this study have been reported previously in the form of an abstract (6).

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of data collected within the SCIP (Simulated Communication in ICU Proxies) study (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT02721810) (7). Briefly, SCIP was a randomized trial that enrolled critical care physicians (intensivists) to participate in a medical simulation. Participants reviewed the medical record of a hypothetical ICU patient on Hospital Day 3 with a mortality of 88% based on the Mortality Probability Model II–72 hours (8, 9), despite appropriate medical management. Intensivists randomized to the intervention responded to the following survey question (response choices yes/no) before participating in a simulated family meeting with an actor portraying the patient’s daughter: “Do you expect this patient to survive to hospital discharge?”

During the simulation, if the intensivist chose to disclose that death was a possible outcome, the actor was trained to respond with surprise, compose herself, and then ask verbatim, “What do you think is most likely to happen?” The actor was instructed not to interrupt the intensivist until he or she finished responding to this scripted question, marking the endpoint of the response. Audio recordings of all encounters were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Our analysis was limited to encounters in which 1) the intensivist reported via presimulation survey that they did not expect the hypothetical patient to survive to hospital discharge, and 2) the actor asked the scripted question verbatim.

Using thematic analysis, three coinvestigators (S.T.V., S.E.Z., A.E.T.) identified patterns of communication within intensivist responses. Patterns were refined by group consensus via iterative rounds of transcript review and discussion. All coinvestigators then agreed on the final codebook. Two coinvestigators (S.T.V., S.E.Z.) independently reread all the transcripts and inductively coded responses using the codebook, with an agreement rate of 80%. Discrepancies were reconciled with a third coinvestigator (M.N.E.). Because this was a secondary analysis, we could not formally assess data saturation, but all of the identified patterns were repeated by at least 10 respondents. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study (IRB 00082272).

Results

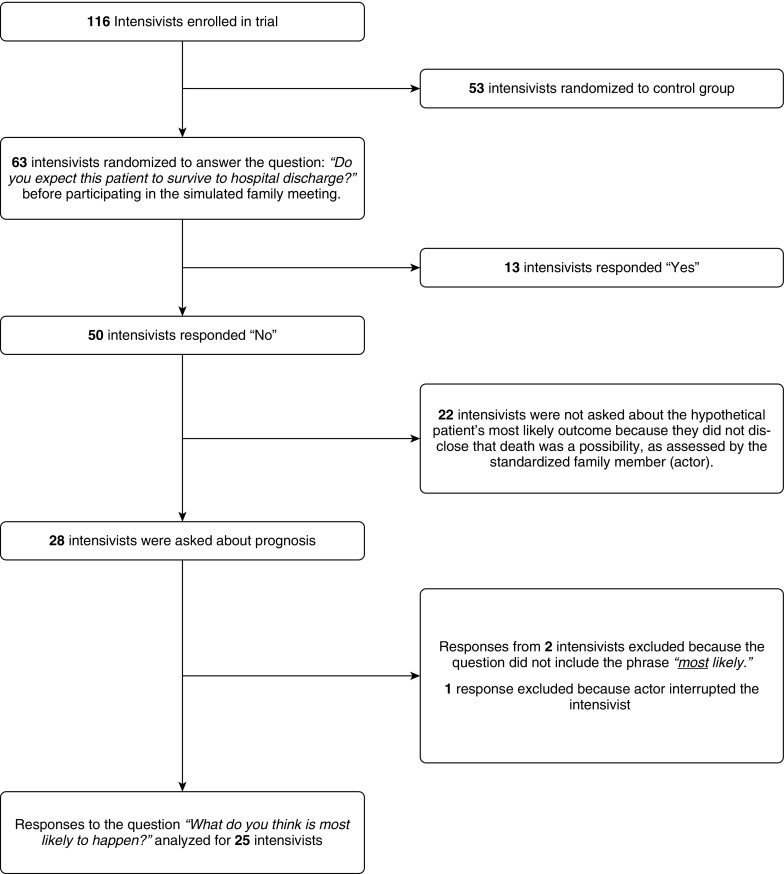

Of the 116 intensivists participating in the SCIP study, 25 indicated that the patient was unlikely to survive to hospital discharge, disclosed that death was a possibility, and were asked by the actor, “What do you think is most likely to happen?” (Figure 1). These intensivists worked at 12 hospitals in six states and completed critical care fellowship a median of 7 years ago.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Intensivists disclosed in two ways that death was possible: suggesting that the patient might not survive without attributing a particular level of risk (n = 19) or expressing concern about death or multiorgan failure (n = 6). We identified four overarching patterns of communication within intensivist responses to the daughter’s subsequent question: direct answers, indirect answers, nonanswers, and redirection. Each pattern contained multiple subtypes, detailed in Table 1. The mean number of words in a response was 204, and the range was from 18 to 995.

Table 1.

Response patterns and representative quotes from intensivists

| Pattern | Subtype | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Direct | Direct response about survival | “I think that he’s going to pass away despite what we’re doing.” |

| Lack of surprise or concern for a poor outcome | “I would not be surprised if he did not survive this hospitalization.” | |

| Portraying a more positive outlook than expected | “I think there’s as good of a chance that he could die during this hospital admission than not.” | |

| Indirect | Using “medical-speak” or describing physiology | “[B]ut I think ... you know ... his ... unless his breathing starts getting better ... his kidney start getting better, I think he’s just going to continue getting worse until ... you know ... we’re not able to give him enough oxygen or we’re not able to support his blood pressure.” |

| Talking about the outcomes of other patients | “Many people like your father that we’ve cared for, they do not survive this type of illness.” | |

| Nonanswer | Expressing empathy | “I’m sorry. I know this must come as a shock to you, especially because he was so well just a couple of days ago.” |

| Expressing uncertainty | “That’s not 100% ... you know ... I’m not omniscient by any means.” | |

| Providing conditional statements (if/then) | “So, if we try to remove some fluid with continuous dialysis, that might allow him to get better somewhat.” | |

| Conveying unrelated information | “I don’t know about his brain, because he’s getting sedation, and we can’t really interact with him. Usually, though, if he were to get over all of this other illness, the brain ... usually recovers.” | |

| Redirection | Transitioning to a discussion of patient goals or treatment limits | “Um ... so, my ... my concern is that we’re not going to be able to reverse this and ... and that makes me want to have a discussion with you to talk a little bit more about what his goals and objectives might be, too.” |

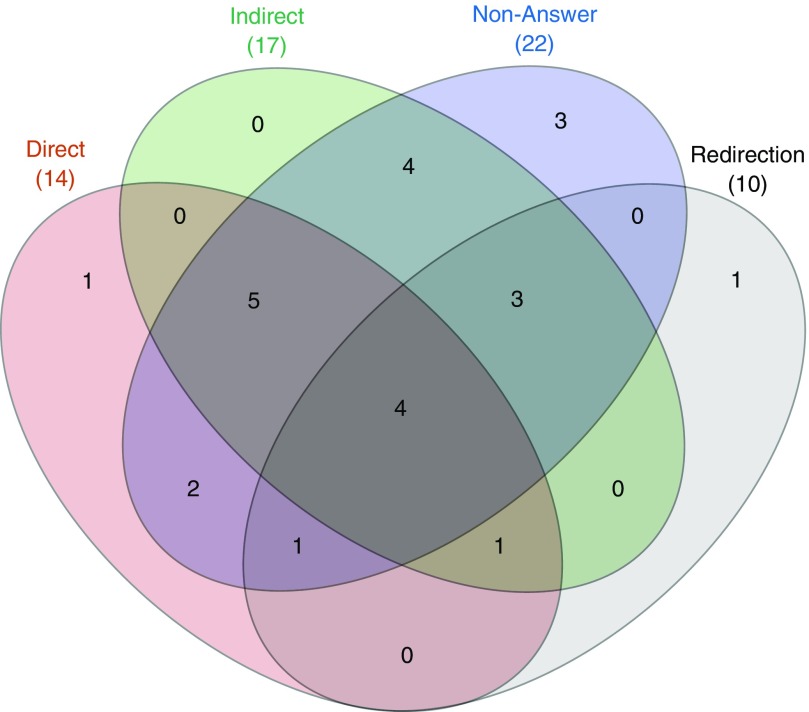

A response was considered direct if it was easily understood as an answer to the daughter’s question. More than half of the intensivists in this study included a direct answer within their response. Many intensivists responded in an indirect way that required interpretation. The most common indirect subtype involved using medical speak to describe the patient’s physiologic condition. Nonanswer statements did not address the daughter’s question about prognosis. These responses included expressions of empathy and support as well as statements of uncertainty. Redirection was used to discuss code status or to describe what survival might entail. Combinations of communication patterns in responses are displayed in Figure 2 (10).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing the distribution of response patterns across 25 intensivists. Each set represents a response pattern: direct (red), indirect (green), nonanswer (blue), and redirection (gray). Overlapping colors indicate that the intensivist’s response contained each of the corresponding patterns.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized how intensivists respond when they expect a patient to die and are explicitly asked about prognosis by the patient’s surrogate. Our findings are consistent with a 2007 analysis which found that intensivists did not discuss prognosis for survival in more than one-third of conferences about whether to forgo life support (11). However, this prior analysis of 35 intensivists used audio recordings of ICU family meetings in which some families may not have wanted information about prognosis. In contrast, our results suggest that a subset of intensivists choose not to discuss prognosis directly even when a family surrogate explicitly requests this information.

It is important to note that although nonanswers were common within responses, we do not believe that most intensivists intended to avoid answering the daughter’s question. The role of nonanswers in this setting is context dependent. For example, expressing uncertainty before answering a surrogate’s question about prognosis is both accurate and appropriate. Similarly, statements of empathy and attending to surrogate emotions are essential to building rapport. More research is needed to understand how nonanswers affect surrogate interpretation.

A limitation of our study was restricting the analysis to responses to a single question contained within a longer encounter. We believe that this approach was appropriate, given our focused research question. The key strength of this study is the use of a standardized surrogate and clinical scenario, which makes response variability attributable only to physicians.

In summary, our study demonstrates the complexity and variability of intensivist responses to a surrogate’s question about prognosis when a patient is likely to die. Our findings raise the possibility that even when physicians have reviewed the same information and reached consensus that a patient is likely to die in the hospital, they may still answer a family’s questions about prognosis in strikingly different ways. Further research is needed to understand how surrogates interpret these complex and sometimes dissimilar responses. We recommend that intensivists exercise self-awareness and answer family surrogates’ explicit questions about prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the intensivists who participated in the original study together with the study actors Barbara King, Hiawatha Howard, and Kecia Campbell. The authors also thank the Johns Hopkins Simulation Center, Pragyashree Sharma Basyal, and Emma Lee for their assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant T32HL007534-36 (S.E.Z.).

Author Contributions: S.T.V.: data collection, interpretation, and writing – original draft preparation and editing. S.E.Z.: data collection, interpretation, and manuscript review and editing. M.N.E.: methodology, interpretation, and manuscript review and editing. A.E.T.: conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, interpretation, and manuscript review and editing.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, Montz K, Hui SL, Slaven JE, et al. Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:370–377. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schenker Y, White DB, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, Tiver GA, Arnold RM. “It hurts to know ... and it helps”: exploring how surrogates in the ICU cope with prognostic information. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:243–249. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orioles A, Miller VA, Kersun LS, Ingram M, Morrison WE. “To be a phenomenal doctor you have to be the whole package”: physicians’ interpersonal behaviors during difficult conversations in pediatrics. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:929–933. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutierrez KM. Experiences and needs of families regarding prognostic communication in an intensive care unit: supporting families at the end of life. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2012;35:299–313. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e318255ee0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel-Boone H, Dokecki PR, Smith MS. Parent and health care provider communication and decision making in the intensive care nursery. Child Health Care. 1989;18:133–141. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc1803_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasher ST, Zaeh SE, Turnbull AE. What do you think is most likely to happen? How intensivists answered a surrogate’s question about prognosis when they expected the patient to die [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A2696. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turnbull AE, Hayes MM, Brower RG, Colantuoni E, Basyal PS, White DB, et al. Effect of documenting prognosis on the information provided to ICU proxies: a randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:757–764. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemeshow S, Klar J, Teres D, Avrunin JS, Gehlbach SH, Rapoport J, et al. Mortality probability models for patients in the intensive care unit for 48 or 72 hours: a prospective, multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1351–1358. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemeshow S, Teres D, Klar J, Avrunin JS, Gehlbach SH, Rapoport J. Mortality Probability Models (MPM II) based on an international cohort of intensive care unit patients. JAMA. 1993;270:2478–2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heberle H, Meirelles GV, da Silva FR, Telles GP, Minghim R. InteractiVenn: a web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:169. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR. Prognostication during physician-family discussions about limiting life support in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:442–448. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254723.28270.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.