Abstract

The organic form of mercurial complex, methylmercury (MeHg), is a neurotoxin that bioaccumulates in the food web. Studies in model organisms, such as Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), provide powerful insights on the role of genetic factors in MeHg-induced toxicity. C. elegans is a free living worm that is commonly cultured in nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with bacteria. The bacteria have broad impact on C. elegans biology, including development, reproduction and lifespan, as well as metabolism of experimental chemicals. We hypothesized that MeHg toxicity in C. elegans could be modified by the bacterial food. Using a C. elegans wild-type (WT) strain and transgenic reporter strains, we found that bacterial food reduced the chronic toxicity of MeHg in C. elegans in a dose- and live-status-dependent manner. The MeHg-induced death rate in C. elegans was highest in fasted worms, followed by dehydrated dead bacteria, dead bacteria and live bacteria fed worms. Among the different bacterial foods, dehydrated dead bacteria fed worms were most sensitive to the toxicity of MeHg. The distinct bacteria food (dehydrated dead bacteria food) attenuated oxidative stress and development delay in C. elegans exposed to MeHg. The FOXO transcriptional factor DAF16 was not changed by MeHg but modified by the distinct bacteria food. Independent of MeHg treatment, daf-16 expression in fed worms migrated from the intestine to muscle. We conclude that, in chronic exposure studies in C. elegans, the effects of bacteria on toxicological outcomes should be considered.

Keywords: methylmercury, C. elegans, bacteria, toxicity

Introduction

Methylmercury (MeHg) is a naturally occurring chemical. Human exposure to MeHg is mainly secondary to consumption of fish. In contaminated areas, such as Minamata Bay, Japan, consumption of MeHg-adulterated fish led to elevated hair Hg level and clinical symptoms of MeHg’s neurotoxicity characterized by ataxia, constriction of visual field, and impairment of speech (Eto, 1997). Though accidental exposure to MeHg in the general population is nowadays rare, exposure to environmental level of MeHg in susceptible populations such as children and pregnant women remains a public health concern (Bellinger et al., 2019). Experimental studies have established no biologically beneficial effect for MeHg, and even exposure to low MeHg levels may lead to neurobehavioral abnormalities (Onishchenko et al., 2007) (Ke et al., 2018).

The neurotoxicity of MeHg has been experimentally investigated in different animal models, including rat (Shinoda et al., 2019), mice (Fujimura et al., 2009), drosophila (Rand et al., 2009), zebrafish (Xu et al., 2012) and C. elegans (Caito and Aschner, 2016). C. elegans is a genetically tractable model that has been used widely in toxicology study. The C. elegans hermaphrodite has 302 uniquely defined neurons that are organized in ganglia in the head and tail regions. More importantly, these neurons are specialized in regulating a plethora of behaviors. MeHg’s neurotoxicity in mammals is characterized by dopaminergic neurodegeneration, and both its behavioral and morphologic sequalae can be replicated in C. elegans (Caito and Aschner, 2016).

C. elegans are commonly cultured in nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with OP50 bacterial food. Various bacterial foods have distinct impact on the biology of C. elegans, ranging from development, reproduction to lifespan (MacNeil et al., 2013). The bacterial food also affects C. elegans response to chemotherapeutics (Garcia-Gonzalez et al., 2017). With respect to metals, such as mercury, bacterial food might potentially affect toxicity. Accordingly, in the current study, we hypothesized that distinct types of bacterial food might modify C. elegans’ response to MeHg. We report that MeHg toxicity is reduced by bacterial food in a dose- and live-status-dependent manner. Furthermore, the toxicity of MeHg in C. elegans is modified by distinct types of bacterial foods. The lowest lethal dose 50 (LD50) of MeHg was found in worms fed with dehydrated dead bacteria. We conclude that, in chronic exposure studies in C. elegans, the effects of bacteria on toxicological outcomes should be considered.

Materials and methods

C. elegans and bacteria strains

C. elegans were maintained at ~20 °C on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with OP50. The strains used in this study were N2, CL2166 (dvIs19 [(pAF15)gst-4p∷GFP∷NLS] III), TJ356 (zIs356 [daf-16p∷daf-16a/b∷GFP + rol-6(su1006)]). The E. coli bacteria used in this study wewe OP50, Na22 and HT115. All C. elegans strain and bacteria were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (University of Minnesota). Worm eggs were harvested by bleaching gravid worms and glucose column separation of eggs and worm corpse. After 18 hours to 20 hours, the newly hatched larvae stage 1 (L1) worms were treated. Bacterial food used in the experiment were freshly (overnight) cultured Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains.

Lethality assay

To reduce the possibility that chemical concentration in NGM agar plate varies due to water evaporation, we developed a lethality assay by treating worms in NGM liquid buffer in 96-well plates. The formula for NGM buffer was the same as for the NGM agar plates, except that the NGM buffer contained no agar. In all lethality experiments, worms were mixed with various types of bacterial food, and then treated with MeHg for 24 hours. The concentration of bacterial food was measured by optical density (OD) at 600 nm (OD600) using microplate reader (BMG, Germany). The concentration of bacteria was titrated with NGM buffer to levels of OD 1.00, OD 1.25 or OD 1.90 with a blank control value of 0.04. Dead bacteria were generated by incubating 1 ml 1:100 (v/v) concentrated overnight cultured bacteria in 80 °C incubator for 1 hour. Dehydrated dead bacteria were generated by incubating 50 μl 1:100 (v/v) concentrated overnight cultured bacteria in 80 °C incubator for 1 hour. After treatment, worms were washed 3 times with M9 buffer, and transferred to OP50 seeded plates. Twenty four hours later, dead worms were counted, and death rate were calculated. For each experiment, ~1,000 worms were treated in 100 μl NGM buffer in sterile 96 well plate (costar, corning), and 200~300 worms were counted for calculation of death rate.

Fluorescence quantification

After treatment and washing, worms were paralyzed by treating 25 mM levamisole and then transferred to agar pads on glass slide. Bright field photos and dark field fluorescence photos were taken by Leica SP8 confocal microscope. The wavelength and energy of excitation were analogous during all the scans. Other parameters, such as magnification factor, emission gating range and scanning speed were also similar. The intensity of fluorescence and the length of worms were measured by Fiji software. Mitotracker™ Red (invitrogen) is a mitochondrion-selective probe that binds with thiol group containing molecules in mitochondria. After treatment, N2 worms were incubated with 10 μM Mitotracker™ Red for 1 hour followed by 15 minutes in Mitotracker™ Red free NGM buffer. After washing 3 times with M9, Mitotracker™ Red strained worms were transferred to agar pads for imaging process.

Development assay

To compare the development stage of worms fed with different foods (Figure 6 B and C), synchronized L1 worms were fed with different food for 24 hours, and then transferred to OP50 seeded NGM agar plate. After 24 hours on the plates, the development stages were checked under stereo microscope (stemi 2000, Zeiss) to observe morphology traits of gonad and vulva development. L1 worms have four mid-ventrally located gonad cells. This number is increased in Larvae stage 2 (L2). Vulva anchor cell appears at early larvae stage 3 (L3), and gonad cells undergo further longitudinal extension. Larve stage 4 (L4) has a characteristic vulva morphology that exhibits a white crescent with a tiny black dot in it.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were shown as mean± SD. Graphpad 7 (La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Comparison of death rates in response to MeHg treatment were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. To analyze the bacterial food effects on MeHg toxicity, two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test were used.

Results

MeHg-induced death rate was reduced in C. elegans fed with bacterial food

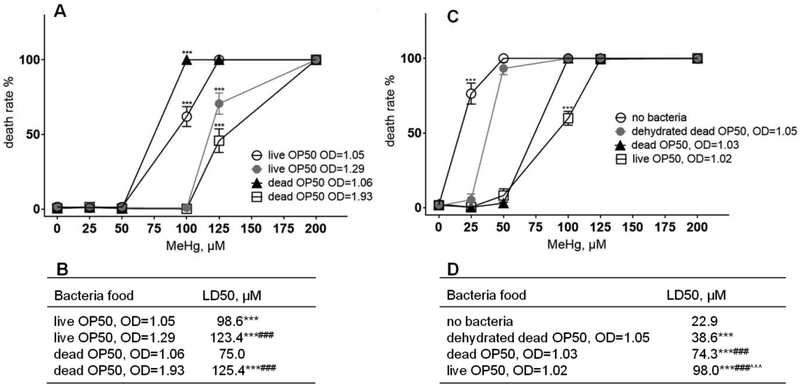

OP50, Na22 and HT115 are the three most commonly used bacteria in C. elegans experiment. OP50 is an uracil auxotroph E. coli B strain that can form a thin bacteria lawn on NGM agar. The advantage of the thin layer of OP50 bacteria lawn is that it permits the morphological visualization of C. elegans under microscope. At the same concentration, live OP50 (OD=1.05) fed worms had a reduced death rate upon treatment with 100 μM MeHg compared to dead OP50 (OD=1.06) fed worms (Figure 1A). Increasing the live OP50 bacteria concentration from OD 1.05 to OD 1.29, fully inhibited the MeHg-induced worm death. However, the inhibition of death rate by dead OP50 bacteria was only apparent at a higher concentration (OD=1.93). Upon treatment with a higher dose (125 μM MeHg), both dead OP50 (OD=1.93) and live OP50 (OD=1.29) partially reduced the death rate (Figure 1A). The protective effects of OP50 bacteria suggested that both passive diffusion and active transport of MeHg into the bacteria might have occurred, reducing the effective concentration of MeHg in the treatment buffer. We carried out the same experiment using Na22 bacteria and HT115 bacteria, and found that these bacteria also afforded worms protection from MeHg toxicity in a dose- and live-status-dependent manner (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Bacteria modify death rates in C. elegans exposed to MeHg. (A) Death rate of 0~ 200 μM MeHg treated L1 stage N2 worms with live OP50 or dead OP50. Data are the mean ± SD of 1,000 worms per treatment. *** p<0.001 for the group vs. other groups per MeHg treatment by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (B) LD50 of MeHg in worms fed with dead or live OP50 bacteria. *** p<0.001 for the group vs. dead OP50, OD=1.06 group; ### p<0.001 for the group vs. live OP50, OD=1.05 group. (C) Death rate of 0~ 200 μM MeHg treated L1 stage N2 worms with or without bacteria food. Data are the mean ± SD of 1,000 worms per treatment. *** p<0.001 for the group vs. other groups per MeHg treatment by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (D) LD50 of MeHg in worms fed with or without OP50 bacteria. *** p<0.001 for the group vs. no bacteria group; ### p<0.001 for the group vs. dehydrated dead OP50 group; ***^^^ p<0.001 for the group vs. dead OP50 group.

MeHg-induced death rate was reduced in C. elegans fed live bacteria

To characterize the bacterial effects on MeHg toxicity, we used a dehydrated dead OP50 by incubating a 50 μl 1:100 (v/v) concentrated overnight cultured OP50 in 1 ml tube in 80 °C incubator. Worms fed with dehydrated dead OP50 had a statistically significant higher death rate upon 50 μM MeHg treatment than worms fed with dead OP50 or live OP50 (Figure 1C). At a higher MeHg dose (100 μM), only worms fed with live OP50 showed statistically significant reduction in death rate, while worms fed with dead OP50 or dehydrated dead OP50 were all dead. This further supports our hypothesis on the existence of an active transport of MeHg in live OP50 bacteria, which lowers the effective concentration of MeHg in the treatment buffer. We further noted that fasted worms were most sensitive to the toxicity of MeHg, followed by dehydrated dead OP50 fed worms, dead OP50 fed worms and live OP50 fed worms (Figure 1D). From these data, we concluded that fasted worms were most susceptible to MeHg’s toxicity.

MeHg’s toxicity in C. elegans was modified by distinct bacterial foods

In the absence of bacteria food, young larvae stage C. elegans will diapause, or arrest at the L1 stage. The relative higher LD50 of MeHg in worms fed with bacteria food could be due to the fact that older larvae stage C. elegans, such as L4 stage, is more resistant to the toxicity of MeHg than younger larvae stage C. elegans, such as L1 stage (Helmcke et al., 2009). However, worms fed with dehydrated dead OP50 showed no difference in body length or percentage of larvae stage (unpublished data) compared to worms fed with live OP50 (Figure 2C). Nevertheless, the LD50 in worms fed with dehydrated dead OP50 was significantly lower than worms fed with live OP50 (Figure 1D). The above result suggests that development could not be the main reason for the resistance to the toxicity of MeHg in worms fed with live OP50.

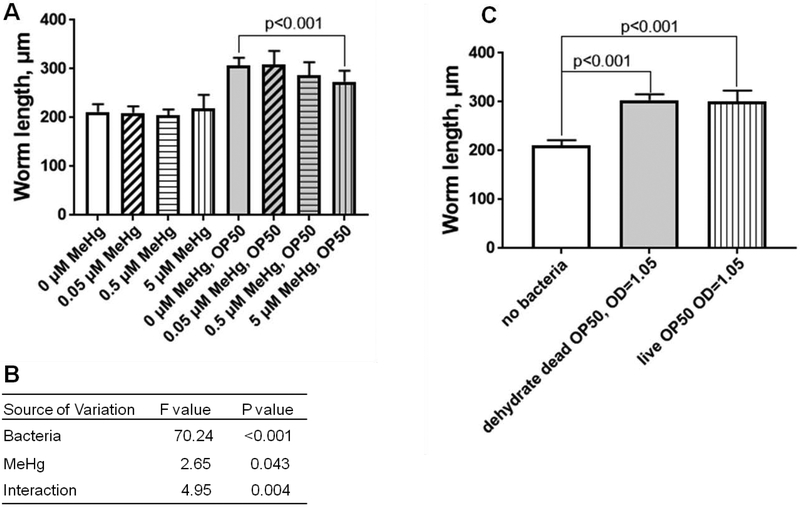

Figure 2.

Body length of C. elegans was shorter following treatment with MeHg. (A) Average body lengths of N2 worms exposed to 0 ~ 5 μM MeHg with or without dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. Data are the mean ± SD of 20~30 worms per treatment. The comparisons were made by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. (B) Summary of statistics of two-way ANOVA analysis. (C) Average body lengths of N2 worms fed with or without bacterial food for 24 hours. The comparisons were made by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

MeHg is known to cause developmental delays in C. elegans (Helmcke et al., 2009). Hence, we analyzed worm length after treatment with 0~5 μM MeHg in the presence or absence of distinct bacterial food. It was noted that 5 μM MeHg reduced the worm length, but the effect was not observed in fasted worms (Figure 2A). Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed that both MeHg and bacterial food had a statistically significant effect on body length, and there was an interactive effect between MeHg and bacterial food (Figure 2B). Our previous work had shown that MeHg-induced developmental delay was independent of food intake indexed by pharyngeal pumping rate (Helmcke et al., 2009). It has also been shown that elevated level of oxidative stress induced larvae arrest (Hu et al., 2017). Therefore, we posited that it might be possible that the developmental delay was induced by MeHg-mediated oxidative stress (Figure 3).

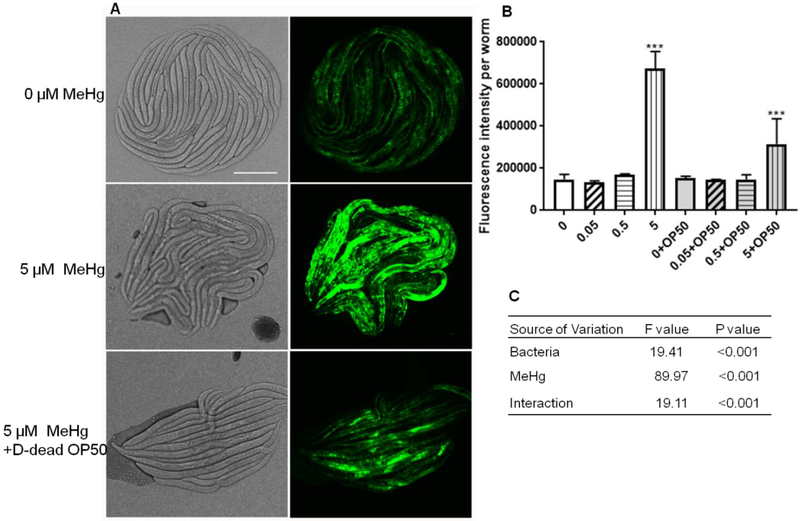

Figure 3.

MeHg-induced gst-4 expression was modified by dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. (A) Representative images of worms exposed to 0 μM MeHg, 5 μM MeHg or 5 μM MeHg plus OD=1.0 dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. D-dead OP50, dehydrated dead OP50. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (B) Quantification of GFP fluorescence of worms exposed to 0~5 μM MeHg with or without dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. Data are the mean ± SD of 20~30 worms per treatment. The comparisons were made by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. (C) Summary of statistics of two-way ANOVA analysis.

We used a GFP reporter strain CL2166 to measure the activity of gst-4 after MeHg treatment. Exposure to 5 μM, but not 0.05 μM MeHg or 0.5 μM MeHg induced statistically significant increase in GFP fluorescence, and analogous effects were noted in worms fed with dehydrated dead bacteria (Figure 3A). However, bacteria fed worms had reduced GFP levels compared to fasted worms. There was a statistically significant interactive effect between MeHg and bacteria on the expression of GFP (Figure 3C), in agreement with the above data on worm body length (Figure 2A, 2B).

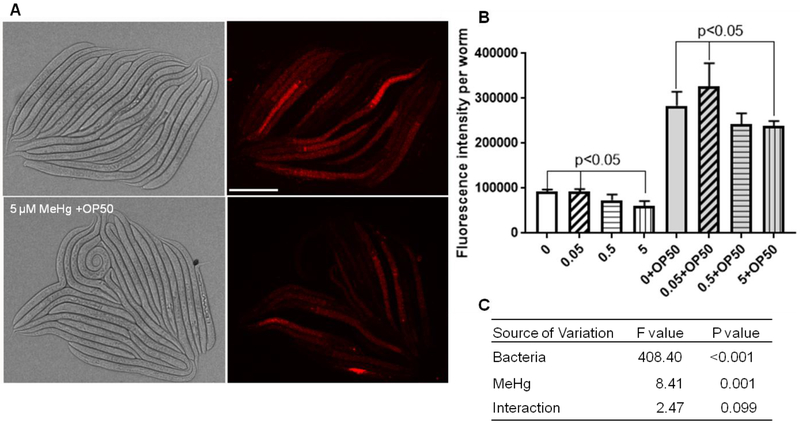

In contrast to promoter driven GFP expression, some molecular probes are absorbed into worms from the intestine. Distinct bacterial foods may have differential effects on the absorption rate of molecular probes. To illustrate these effects in C. elegans, we used a commercial mitochondrial probe, MitoTracker Red, which specifically binds with thiol molecules in mitochondria. Upon treatment with 0~5 μM MeHg in the absence of bacterial food, 5 μM MeHg treated worms exhibited lower fluorescence levelthan 0 μM or 0.05 μM MeHg treatment worms (Figure 4). When fed dehydrated dead OP50 (OD=1.00), significantly lower fluorescence levels in worms treated with 5 μM MeHg was noted (Figure 4). In two-way ANOVA analysis, both bacteria and MeHg significantly contributed to the variation in the fluorescence level (Figure 4C). However, there was no interactive effect between MeHg and bacteria.

Figure 4.

MeHg’s effects in Mitochondria were not modified by dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. (A) Representative images of worms exposed to 0 or 5 μM MeHg plus OD=1.0 dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (B) Quantification of RFP fluorescence of worms exposed to 0~5 μM MeHg with or without dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. Data are the mean ± SD of 20~30 worms per treatment. The comparisons were made by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Summary of statistics of two-way ANOVA analysis.

Worms treated in the absence of bacterial food would diapauses (Figure 2). Several genes have been found to participate in the initiation of development of larvae arrested C. elegans (Baugh, 2013). Here we focused on daf-16, C. elegans homolog of mammalian FOXO transcriptional factor (Baugh and Sternberg, 2006). It has been previously noted that daf-16 played an important role in stress response of C. elegans to metals, such as cadmium and manganese (Keshet et al., 2017,Chen et al., 2015). We queried whether daf-16 expression was affected by MeHg and modified by distinct bacterial food. We found that MeHg failed to alter the expression of daf-16, though its level in bacteria fed worms was higher than in starved worms (Figure 5G, 5H). Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect only for bacteria. In agreement, in worms fed with dehydrated dead OP50, we observed migration of daf-16 expression from intestine cells (Figure 5B, 5C) to muscle cells (Figure 5E, 5F).

Figure 5.

The expression of daf-16 was migrated from the intestine to the muscle in C. elegans fed with dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. (A-F) Representative image of worms exposed to 0 μM MeHg with or without dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. (A) Bright field image of fasted worms. (B) Image of daf-16 promoter driven GFP corresponding to (A). (C) Magnification of part of (B) showing the daf-16p∷daf-16a/b∷GFP expression are mainly in the intestine. (D) Bright field image of worms fed with dehydrated dead OP50. (E) Image of daf-16 promoter driven GFP corresponding to (D). (F) Magnification of part of (E) showing the daf-16p∷daf-16a/b∷GFP expression are mainly in the muscle. (G) Quantification of GFP fluorescence of worms exposed to 0~5 μM MeHg with or without dehydrated dead OP50 bacteria food. Data are the mean ± SD of 20~30 worms per treatment. (H) Summary of statistics of two-way ANOVA analysis. The comparisons were made by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

In this study, we show for the first time that the toxicity of MeHg in C. elegans was attenuated by OP50 bacterial food. A higher concentration of bacteria and live bacteria-fed worms were more resistant to the toxicity of MeHg (Figure 1A, 1B). In bacteria-fed worms, dehydrated dead OP50-fed worms were more susceptible to the toxicity of MeHg than dead OP50 or live OP50 fed worms (Figure 1C, 1D). Both bacterial food and MeHg have an effect on the development and oxidative stress response in C. elegans (Figure 2, 3), and bacterial food mitigates the oxidative effect of MeHg (Figure 3). Although bacteria food might increase absorption of MitoTracker, we failed to show an interactive effect with MeHg (Figure 4). Independent of MeHg treatment, daf-16 expression in bacteria-fed worms was mainly localized to the muscle, while in fasted worms its expression was mainly inherent to the intestine (Figure 5).

The protective effect of bacteria on MeHg-induced worm death rate might be explained by the buffering effect of bacteria on MeHg concentration. We didn’t measure mercury content in worms and bacteria, respectively, but data from dead bacteria and live bacteria experiments (Figure 1) suggested that the protective effect of live bacteria might be explained by the active transport of MeHg into live bacteria. It was previously hypothesized that MeHg might be actively transported into E. coli by a cysteine transport system (Ndu et al., 2012). The lower LC50 in worms fed with dehydrated dead bacteria also supports the notion that MeHg might be passively diffusing into bacteria, given of lesser hydrophilic space in dehydrated dead bacteria. Indeed, it has been shown that neutrally charged complex of MeHg could be passively diffused into microorganism (Benoit et al., 2001). Our data suggest that among the different bacterial foods, dehydrated dead bacteria fed worms remains most sensitive to chronic treatment of MeHg.

In the current study, we used NGM as treatment buffer. NGM contains 0.25% peptone. It is reported that naturally dissolved organic carbon facilitated transport of Hg2+ to aquatic bacteria (Kelly et al., 2003). It is possible that MeHg+ could bind with relatively higher molar ratio of peptides in the solution, and be transported into bacteria by a specific transporter, such as ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC transporters) (Linton and Higgins, 1998). In nature, about 1-10% bacteria are resistance to toxicity of mercury. The mer operon that governs genes to transform organic mercury or inorganic mercury to gaseous elemental mercury, has been well characterized in some of these bacteria (Ndu et al., 2016). OP50 is an E. coli B strain, which supposedly has no mer operon (Chien et al., 2010). We didn’t find significant inhibition of bacterial growth by MeHg in the treatment solution (unpublished data). However, MeHg could inhibit the growth rate of the log phase bacteria. Further studies on characterization of transport of MeHg in OP50 and its significance in MeHg toxicity in C. elegans are warranted.

The lower activity of gst-4 in worms fed with dehydrated dead bacteria compared with fasted worms (Figure 3) might be an effect of development in fed worms or caused by that the complex of organic or inorganic ligands in digested components of bacteria food with MeHg could potentially influence its bioavailability (Ndu et al., 2012). In a chronic MeHg exposure study, MeHg-cysteine complex treated mice had a higher brain and liver mercury level, but lower kidney mercury level than MeHgCl treated mice (Roos et al., 2010). Chemically, the mercurial species that were absorbed into worm’s intestine cells presumably include complex of digested components of bacterial food with MeHg. However, the predominant species of mercury that were absorbed and the bioactive form have yet to be identified. In rats, it was found that MeHg induced oxidative stress and mitochondria damage is age-dependent (Dreiem et al., 2005). Further studies with different ligands, organic or inorganic, to compare gst-4 activity as well as other oxidative stress markers in different developing stage worms are warranted.

In prolonged fasted worms, an alternative long-lived, stress resistance form of developmental stage named dauer larvae or dauer will appear (Fielenbach and Antebi, 2008). The migration of daf-16 expression in fed worms from the intestine to the muscle (Figure 5) suggests that, DAF-16 activity in the intestine in fasted worms might play an important role in developmental arrest and dauer formation, while its activity in the muscle might participate in initiation of development or a consequent event of development. In agreement, it has been previously shown that DAF-16 in the intestines could completely restore the longevity of daf-16(−) germline deficient worms (Libina et al., 2003). Given that intranuclear abundance of DAF-16 is not correlated with its transcriptional activity and DAF-16 has important role in metal detoxification (Barsyte et al., 2001), we could not preclude possible roles of DAF-16 in MeHg toxicity. To determine this possibility, further studies in daf-16 transgenic strain as well as daf-16 mutant stain are warranted.

Given the electrophilic property of MeHg its toxic effects are inherent to multiple cellular sites. Mercury is localized to lysosomes (Eto, 1997), and causes autophagic dysfunction (Yuntao et al., 2016). MeHg has also been recognized as a mitochondrial toxin (Caito and Aschner, 2016). In rats, MeHg inhibits complex II activity in mitochondria (Mori et al., 2011). The low fluorescence in MeHg treated worms is likely caused by depletion of free thiol containing molecules in mitochondria (Figure 4). The effect of MeHg was not masked by the higher absorption rate of Mitotracker in fed worms, which was not anticipated. However, we also observed a relatively higher fluorescence in 0.05 MeHg treatment group in fed worms (Figure 4), suggesting more sophisticated modeling must be employed to further characterize the interaction between MeHg and bacterial food.

Conclusions

In summary, our data showed that bacterial food reduced the chronic toxicity of MeHg in C. elegans in a dose- and live-status-dependent manner. The MeHg-induced death rate in C. elegans was highest in fasted worms, followed by dehydrated dead bacteria fed worms, dead bacteria fed worms and live bacteria fed worms. Among the different bacterial foods, dehydrated dead bacteria fed worms remains most sensitive to chronic treatment of MeHg. MeHg-induced development delay and oxidative stress are attenuated by the dehydrated dead bacteria food. DAF-16 expression level was not changed by MeHg but modified by the dehydrated dead bacteria food. Independent of MeHg treatment, daf-16 expression in fed worms migrated from the intestine to the muscle. We conclude that, in chronic exposure studies in C. elegans, the effects of bacteria on toxicological outcomes should be considered.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Félix Alexandre Antunes Soares for his helpful comments. We thank the Analytical Imaging Facility (AIF) at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, which is sponsored by NCI cancer center support grant [P30CA013330] and Shared Instrumentation Grant (SIG) [1S10OD023591-01].This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health to MA [grant numbers NIEHS R01ES007331, NIEHS R01ES010563 and NIEHS R01ES020852]. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs [P40 OD010440].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barsyte D, Lovejoy DA, and Lithgow GJ (2001). Longevity and heavy metal resistance in daf-2 and age-1 long-lived mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 15, 627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, DeWitt MR, Bornhorst J, Soares FA, Mukhopadhyay S, Bowman AB, and Aschner M (2015). Age- and manganese-dependent modulation of dopaminergic phenotypes in a C. elegans DJ-1 genetic model of Parkinson's disease. Metallomics. 7, 289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh LR (2013). To grow or not to grow: nutritional control of development during Caenorhabditis elegans L1 arrest. Genetics. 194, 539–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh LR and Sternberg PW (2006). DAF-16/FOXO regulates transcription of cki-1/Cip/Kip and repression of lin-4 during C. elegans L1 arrest. Curr. Biol 16, 780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DC, Devleesschauwer B, O'Leary K, and Gibb HJ (2019). Global burden of intellectual disability resulting from prenatal exposure to methylmercury, 2015. Environ. Res 170, 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caito SW and Aschner M (2016). NAD+ Supplementation Attenuates Methylmercury Dopaminergic and Mitochondrial Toxicity in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Toxicol. Sci 151, 139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto K (1997). Pathology of Minamata disease. Toxicol. Pathol 25, 614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Usuki F, Sawada M, and Takashima A (2009). Methylmercury induces neuropathological changes with tau hyperphosphorylation mainly through the activation of the c-jun-N-terminal kinase pathway in the cerebral cortex, but not in the hippocampus of the mouse brain. Neurotoxicology. 30, 1000–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez AP, Ritter AD, Shrestha S, Andersen EC, Yilmaz LS, and Walhout AJM (2017). Bacterial Metabolism Affects the C. elegans Response to Cancer Chemotherapeutics. Cell. 169, 441.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmcke KJ, Syversen T, Miller DM, and Aschner M (2009). Characterization of the effects of methylmercury on Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 240, 265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, D'Amora DR, MacNeil LT, Walhout AJM, and Kubiseski TJ (2017). The Oxidative Stress Response in Caenorhabditis elegans Requires the GATA Transcription Factor ELT-3 and SKN-1/Nrf2. Genetics. 206, 1909–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke T, Goncalves FM, Goncalves CL, Dos Santos AA, Rocha JBT, Farina M, Skalny A, Tsatsakis A, Bowman AB, and Aschner M (2018). Post-translational modifications in MeHg-induced neurotoxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton KJ and Higgins CF (1998). The Escherichia coli ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol. Microbiol 28, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil LT, Watson E, Arda HE, Zhu LJ, and Walhout AJ (2013). Diet-induced developmental acceleration independent of TOR and insulin in C. elegans. Cell. 153, 240–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishchenko N, Tamm C, Vahter M, Hokfelt T, Johnson JA, Johnson DA, and Ceccatelli S (2007). Developmental exposure to methylmercury alters learning and induces depression-like behavior in male mice. Toxicol. Sci 97, 428–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MD, Dao JC, and Clason TA (2009). Methylmercury disruption of embryonic neural development in Drosophila. Neurotoxicology. 30, 794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda Y, Ehara S, Tatsumi S, Yoshida E, Takahashi T, Eto K, Kaji T, and Fujiwara Y (2019). Methylmercury-induced neural degeneration in rat dorsal root ganglion is associated with the accumulation of microglia/macrophages and the proliferation of Schwann cells. J. Toxicol. Sci 44, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Weber D, Carvan MJ, Coppens R, Lamb C, Goetz S, and Schaefer LA (2012). Comparison of neurobehavioral effects of methylmercury exposure in older and younger adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Neurotoxicology. 33, 1212–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshet A, Mertenskotter A, Winter SA, Brinkmann V, Dolling R, and Paul RJ (2017). PMK-1 p38 MAPK promotes cadmium stress resistance, the expression of SKN-1/Nrf and DAF-16 target genes, and protein biosynthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Genet. Genomics 292, 1341–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]