Abstract

Introduction

People with serious mental illness may be subjected to “court-ordered treatment” (COT), per the mental health statutes of their respective state. COT enforces adherence to a psychiatric treatment regimen and may involve involuntary medication administration. Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics are frequently used in this setting, although little is known about the clinical effectiveness or patterns of use of these agents in the context of COT. Because psychiatric pharmacists are medication experts, we sought to characterize their perceptions and experiences on this topic.

Methods

A cross-sectional, electronic, 14-item survey was administered via the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists listserv from October 9, 2018, to November 9, 2018. The survey collected demographic information, experience and use of LAI antipsychotics at each practice site, and perception of LAI antipsychotics.

Results

Of 843 possible respondents, 72 completed the survey, yielding an 8.5% response rate. LAIs were perceived as underused or adequately used as a whole, with a significant difference in perception favoring the opinion that LAIs are underused versus overused for those respondents who perceived an adherence benefit (P = .042). We also found that LAIs were used disproportionately in the context of COT versus oral formulations (P = .03).

Discussion

The use of LAIs in the context of COT has not been studied, and it may expose this vulnerable population to adverse effects from medications they are legally compelled to take. Further research on the perceptions of other interdisciplinary team members and the clinical impact of LAI use in COT is needed.

Keywords: long-acting injectable antipsychotic, commitment, court-ordered treatment, court-ordered medication management, involuntary medication administration, survey

Introduction

Individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) frequently receive care within hospitals, both voluntarily and involuntarily. The statutes for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization regulate complex medicolegal processes that vary from state to state. In 2017, it was estimated that 11.2 million adults in the United States have SMI, representing 4.5% of all adults.1 People with SMI presenting to a hospital with symptoms of mania or psychosis may, in accordance with state mental health statutes, be held involuntarily for evaluation and stabilization. The psychiatric treatment team may additionally seek a court order for continued hospitalization and/or outpatient treatment. Although this is sometimes referred to as “commitment,” here we use the more precise term “court-ordered treatment” (COT) to avoid confusion. Court orders may or may not permit involuntary medication administration, or “court-ordered medication management.” Upon discharge, outpatient treatment may contain provisions for readmission to an inpatient psychiatry unit (and potential involuntary medication administration) in cases of medication nonadherence. Although some nonprofit advocacy groups, such as Mental Health America, oppose the provision of outpatient COT,2 other stakeholders, including the American Psychiatric Association, have adopted positions in support of outpatient COT laws.3 In contrast to the medical profession, professional organizations within pharmacy have not formalized position statements on the matter. State mental health statutes often vary by the duration and necessary findings to court order treatment for a person. Although all states provide statutory support for inpatient COT, only Connecticut, Maryland, and Massachusetts do not explicitly provide statutory support for outpatient COT.

Psychiatric pharmacists participate in the interdisciplinary care of individuals with SMI. For psychiatric pharmacists, an understanding of state mental health statutes is key to collaborating with other health care providers to provide ethical, legal, and evidence-based pharmaceutical care. Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics are frequently used for patients with SMI, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, in both inpatient and outpatient settings.4 Long-acting injectables are designed to provide a continuous dose of an antipsychotic during a long period of time, and they have been promoted as tools to enhance adherence.4 However, there are no randomized, clinical trials of LAIs that include people receiving COT, nor are there retrospective studies evaluating clinical or psychosocial outcomes in people on COT and LAIs. Because psychiatric pharmacists are on the front lines of medication management, we sought to characterize their experience and perception with LAIs in the context of COT.

Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional, web-based survey (Table 1) was sent via email to the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP) listserv from October 9, 2018, to November 9, 2018 via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Nashville, TN).5 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. Data were collected anonymously and voluntarily. Potential respondents were not offered incentives for participation, nor were they penalized for declining participation. Respondents were allowed to skip any questions they did not wish to answer.

TABLE 1.

Data collection instrumenta

|

Item |

Response |

| 1. In what state do you currently practice? | [Drop-down list of states by abbreviation] |

| 2. How many years have you practiced pharmacy in your state? | [Field limited to numbers only] |

| 3. Which best describes your primary clinical practice site? |

|

| 4. Are long-acting injectable antipsychotics used in your clinical practice? |

|

| 5. In your practice, do you think long-acting injectable antipsychotics are utilized: | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 4]

|

| 6. In your opinion, how often do you estimate long-acting injectable antipsychotics improve adherence for your patients? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 4]

|

| 7. In your state, can court-ordered treatment include long-acting injectable antipsychotics? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 4]

|

| 8. What percent of outpatient court-ordered treatment do you estimate includes a long-acting injectable antipsychotic? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 7] [Slider, 0 to 100] |

| 9. What percent of long-acting injectable use do you estimate is part of outpatient court-ordered treatment? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 7] [Slider, 0 to 100] |

| 10. Do you, or pharmacists at your site, administer long-acting injectable antipsychotics as part of court-ordered treatment? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 7]

|

| 11. How often do your patients on court-ordered long-acting injectable antipsychotics self-discontinue medication when the court order expires? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 7]

|

| 12. In your practice, what are the top three long-acting injectable antipsychotics that are utilized? | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 4] [Maximum select = 3]

|

| 13. Which sample medications or manufacturer replacement programs does your site utilize? Select all that apply. | [Branching logic: must have selected “Yes” to item 4]

|

| 14. Please include any other comments or concerns regarding court-ordered long-acting injectable antipsychotics. | [Free response] |

VA = Veterans Affairs.

Items are listed in the order in which they were presented. Programmed restrictions on the availability of items or responses to items are indicated in brackets.

This study was determined to be exempt from full review by the Michigan Medicine Institutional Review Board, and was approved for distribution by the CPNP Board of Directors.

Population of Interest

All respondents were current members of CPNP. As of 2018, CPNP consisted of 2566 members, most of whom were licensed pharmacists, representing the largest association of psychiatric and neurologic pharmacists in the United States. About 65% of CPNP members were credentialed as Board Certified Psychiatric Pharmacists.6 As of October 10, 2018, a total of 754 members received individual listserv emails, whereas another 89 received daily digests summarizing listserv communication, for a total population of 843 possible respondents (G. Payne, personal communication, October 2018).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis included descriptive statistics using means, medians, and percentages as appropriate. Univariate inferential statistics included 2-sided Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact test (if counts were less than 5) for dichotomous variables, and 2-sided Student t-test for continuous variables. One-way analysis of variance with Bartlett test for equal variances was used to compare the perception of an adherence benefit with LAI antipsychotics between groups of differing LAI antipsychotic use perception, with Bonferroni, Scheffe, and Sidak multiple comparison sensitivity analyses. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

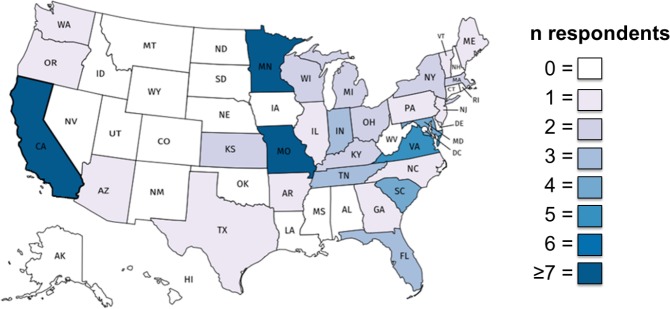

A total of 72 pharmacists completed the survey, representing an 8.5% response rate (72 of 843). The time spent practicing pharmacy in their state of residence ranged from 0.33 to 42 years, with a median of 8 years (interquartile range, 4-17 years). Most respondents practiced inpatient pharmacy, of which most were unaffiliated with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). This may represent a sampling bias toward inpatient, non-VA sites—in 2018, “government supported hospitals” represented the largest CPNP membership affiliation at 36%, followed by community or university hospitals at 23% (V. Wasser, personal communication, September 2019). State representation varied (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

State representation of survey respondents; a choropleth map of the United States, visualizing the state representation of survey respondents (darker colors represent more respondents)

Perceptions

When asked whether LAIs can be used as part of COT in their respective states, 20% of respondents indicated that they could not (or did not answer). Long-acting injectables were generally perceived as underused (41%) or adequately used (48%), with few believing that LAIs were overused (11%). The perception of an adherence benefit formed a bell curve, with the largest proportion (36%) believing that LAIs provided a 26% to 50% adherence benefit, 26% endorsing an adherence benefit of 25% or less, 28% endorsing a benefit of 51% to 75%, and 10% endorsing a benefit greater than 75%. When stratified by perception of use group, the perception of an adherence benefit varied (1-way analysis of variance, F2,66 = 3.32, P = .042), with a significant between-group comparison between the underused and overused perception groups (Bonferroni P = .040; Scheffe P = .046; Sidak P = .040).

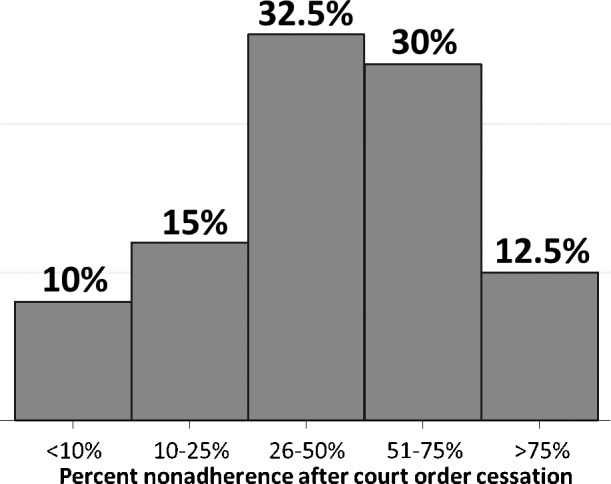

Experiences

To assess pharmacists' experience with COT as an adherence-promoting tool, respondents were asked to estimate what percent of their patients stopped treatment after the expiration of a court order. Nearly half (43%) estimated that most of their patients stopped treatment after their court orders expired (Figure 2). Respondents reported that 49% ± 27% of all outpatient COT involved the use of an LAI. Comparatively, respondents reported that 36% ± 24% of all LAI use occurred in the setting of COT. In other words, although use of LAIs is common outside of COT, a disproportionate percentage of patients with COT receive LAIs. Therefore, it is the experience of our respondents that LAIs are disproportionately used in the setting of COT, compared with other settings (t-test, P = .03).

FIGURE 2.

Perception of percent nonadherence after court order cessation; a histogram of respondents' views regarding what percent of their patients they estimate to discontinue therapy upon expiration of their court order

When asked to rank the top 3 most commonly used LAIs at their institutions, the most frequently reported LAIs (frequency, percent) were paliperidone palmitate (68, 94%), haloperidol decanoate (49, 68%), and aripiprazole monohydrate (42, 58%). Use of sample or manufacturer replacement programs were most commonly reported for paliperidone palmitate (36, 50%), aripiprazole monohydrate (33, 45.8%), and aripiprazole lauroxil (15, 20.8%). When the top 3 most commonly used LAIs were compared against the use of sample or manufacturer replacement programs, the association was statistically significant for aripiprazole monohydrate (χ2 [71 df, n = 72] = 7.61, P = .0058), but not for paliperidone palmitate (Fisher exact, P = .61) and haloperidol decanoate (χ2 [71 df, n = 72] = 0.42, P = .51). No association was found between the use of sample or manufacturer replacement programs and perception of use (Fisher exact, P = .655), including aripiprazole monohydrate alone (χ2 [68 df, n = 69] = 0.79, P = .67).

Free Response Comments

The last question on the survey allowed for free-text response, and 36% of respondents included comments. Feedback spanned the spectrum of support for COT with LAIs. Examples (lightly edited for clarity) include:

“…I usually align with court-ordered administration if there is a significant history of violence towards self/others during a period of untreated mental illness/substance use disorder that does not occur when the patient is undergoing treatment.”

“I feel that our providers administer LAIs too quickly without first determining what the patient's oral equivalent dose is to determine how to appropriately dose subsequent maintenance injections.”

“The notion of court-ordered LAIs makes my ethical sensor vibrate a bit.”

“I have not found LAIs to improve adherence if patients do not want to take antipsychotics, as they only choose not to attend their appointments.”

Discussion

This survey represents the first assessment of pharmacists' perceptions and experiences with LAIs in the context of COT. There is room for improvement regarding knowledge of the legality of LAI use in this setting because psychiatric pharmacists may receive questions regarding the use of LAIs under COT. Review of the state laws in each state for which a respondent reported that LAIs cannot be used as part of COT found that all of them allowed for (or did not specifically prohibit) the use of LAIs in this context (Table 2). Respondents from Massachusetts and Maryland who believed that LAIs cannot be used as part of COT may have been speaking to the lack of statutory support for outpatient COT, although (1) this does not preclude the use of LAIs prior to discharge and (2) there are nonstatutory methods of achieving a similar legal outcome to outpatient COT in these states. For example, in Massachusetts, following the appointment of a legal guardian on the basis of a lack of capacity, LAIs may be administered involuntarily if the guardian assesses that the ward (the patient) is incapable of making their own medical decisions. It should be noted that the process of appointing a guardian assumes a chronic lack of capacity to make decisions and is a more involved process than COT.

TABLE 2.

Court-ordered treatment lawsa

|

State |

Citation |

| CA | WIC.5345 |

| FL | FS 394.4655(3)(a)(3) |

| IL | ILCS 3-704, 3-608 |

| IN | IN CODE 12-27-5-2 |

| KY | KRS 202A.0817 |

| MA | MGL 123.8B |

| MD | MD 10-708(b) |

| ME | MRS 3861.3 |

| MN | MS 253B.092.2 |

| MO | RSMO 630.050; DOR 4.152 |

| NC | NCGS 122C-265 |

| NJ | NJRS 30:4-27.15a, 30:4-27.2 |

| OH | ORC 5122.11 |

| OR | ORS 426.133 |

| SC | SC CODE 44-22-140 |

| VA | COV 37.2-1102 |

For those respondents who responded long-acting injectable antipsychotics could not be used in the setting of court-ordered treatment (or did not respond), this table represents a list of legal citations from their representative states, permitting their use in this context.

The perception of LAI use as a whole varied, although few pharmacists believed they were overused. In the present survey, the perception of an adherence benefit was higher in those who perceived LAIs to be underused compared with overused. Our study's attempt to quantify the perception of an adherence benefit to LAIs found a bell curve, with 74% of the distribution endorsing that LAIs would improve adherence for their patients more than 25% of the time. This is in agreement with a previous study on psychiatric nurses across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, most (92%) of whom believed that continuous medication with an LAI would improve outcomes for patients with schizophrenia.7 In the same survey, administered to psychiatrists, 46% preferred switching to LAIs to address adherence problems.8

Many pharmacists who completed the survey perceived an adherence benefit of COT, with 43% believing that patients would discontinue treatment when the court order expired. This is at odds with a 2017 Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of n = 3 studies, which failed to detect a difference in health service outcomes (readmission and medication adherence at 11 to 12 months) comparing voluntary to involuntary treatment for patients with SMI (low-quality evidence).9

Sample or manufacturer replacement programs are both a form of compassion by pharmaceutical companies, increasing access to medications, and advertising, allowing the company to “get their foot in the door” with the goal of increasing use.10 The effect of these programs on LAI use remains unanswered. Although our study detected an association between the use of such programs and selection as a “top 3” LAI for the choice of aripiprazole monohydrate, this was not true for other LAIs. Despite this finding, we failed to detect an association between these programs and the overall perception of use. Further research is needed to clarify how the availability and use of sample or manufacturer replacement programs for LAIs impact use.

Our study found that LAIs are being used more frequently in the context of COT, perhaps reflecting the perceived adherence benefit on behalf of psychiatric teams. We did not ask what percentage of patients who were not under COT were on LAIs; a perceived 50% use is greater than would be expected in a voluntary population. This is important because, to our knowledge, LAIs have not been specifically studied in COT populations. In conferring with the medical information departments of both Janssen Global Services LLC and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (the manufacturers of paliperidone palmitate and aripiprazole monohydrate, respectively), patients on COT were either excluded from clinical trials, or their legal status was not recorded (Janssen Medical Information Department, personal communication, December 2018; Otsuka Medical Information Department, personal communication, December 2018). This is of special concern in a population that is legally compelled to take medications, including antipsychotics, which may have serious adverse effects, including dystonia, akathisia, and hyperglycemia.11,12 Studies are needed to clarify the safety and efficacy (including psychosocial outcomes) of these agents in a COT population.

The ethical concerns of performing human subject research in the vulnerable population of patients on COT is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth pointing out that there is precedent for research in this population; for example, Swartz et al13 discuss their experience with a randomized, controlled trial in North Carolina, in which involuntary inpatients were randomized to outpatient COT plus case management versus case management alone. Although the ethical challenges are numerous, courageous clinician-scientists are needed to forward our scientific understanding of how best to provide care for this population.

The present study has several limitations. Our response rate was low in comparison with previous literature; 1 survey of CPNP members with board certification in psychiatric pharmacy practice and affiliated with an academic institution had a survey response rate of 65% (173 of 267).14 However, our survey was open for a much shorter duration of time (4 weeks vs 4 months), was sent to the entire listserv (which may have included members who did not work with LAIs), and did not send reminders. We also did not use a multimodal approach, which has been associated with higher response rates.15 Our results should be interpreted in the context of our limited sample; for example, our data do not reflect the perceptions and experiences of pharmacists from several western states. Other possible limitations include recall bias, because respondents were asked to estimate their experience retrospectively, and sampling bias, because respondents were only able to receive study invitations via an electronic medium.

Conclusion

Our survey of psychiatric pharmacists suggests that LAIs are disproportionately used in the setting of COT compared with patients with voluntary status, despite the lack of data in patients undergoing COT. Pharmacists may be unfamiliar with details of the laws in their respective states as they pertain to the use of medications in the setting of COT, indicating an opportunity for education. Future studies should explore how perceptions of interdisciplinary team members guide the prescribing of LAIs in the context of COT.

References

- 1.The National Institute of Mental Health Information Resource Center; c2017. Mental illness [Internet] Nov [cited 2018 Dec 28] Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental Health America; c2019. Position statement 22: involuntary mental health treatment [Internet] [cited 2019 Jul 11] Available from: https://mhanational.org/issues/position-statement-22-involuntary-mental-health-treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association; c2015. Position statement on involuntary outpatient commitment and related programs of assisted outpatient treatment [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 28] Available from: http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2015-Involuntary-Outpatient-Commitment.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):306–24. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000388626.98662.a0. DOI: 10.1097/01.pra.0000388626.98662.a0 PubMed PMID: 20859108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 PubMed PMID: 18929686 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2700030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP); c2019. Member profile [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 28] Available from: https://cpnp.org/_docs/ed/meeting/2019/supporter/member-profile.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emsley R, Alptekin K, Azorin JM, Cañas F, Dubois V, Gorwood P, et al. Nurses' perceptions of medication adherence in schizophrenia: results of the ADHES cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Ther Adv In. 2015;5(6):339–50. doi: 10.1177/2045125315612013. DOI: 10.1177/2045125315612013 PubMed PMID: 26834967 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4722504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivares JM, Alptekin K, Azorin JM, Cañas F, Dubois V, Emsley R, et al. Psychiatrists' awareness of adherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia: results from a survey conducted across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:121–32. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S37534. DOI: 10.2147/PPA.S37534 PubMed PMID: 23390361 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3564476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kisely SR, Campbell LA, O'Reilly R. Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub5. CD004408. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub5 PubMed PMID: 28303578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chimonas S, Kassirer JP. No more free drug samples? PLoS Med. 2009;6(5):e1000074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000074. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000074 PubMed PMID: 19434227 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2669216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JJ. Drug-induced movement disorders. Ment Health Clin [Internet] 2012;1(7):167–73. doi: 10.9740/mhc.n90206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei Xin Chong J, Hsien-Jie Tan E, Chong CE, Ng Y, Wijesinghe R. Atypical antipsychotics: a review on the prevalence, monitoring, and management of their metabolic and cardiovascular side effects. Ment Health Clin [Internet] 2016;6(4):178–84. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.07.178. DOI: 10.9740/mhc.2016.07.178 PubMed PMID: 29955467 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6007719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz MS, Burns BJ, George LK, Swanson J, Hiday VA, Borum R, et al. The ethical challenges of a randomized controlled trial of involuntary outpatient commitment. J Ment Health Adm. 1997;24(1):35–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02790478. DOI: 10.1007/BF02790478 PubMed PMID: 9033154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dopheide JA, Bostwick JR, Goldstone LW, Thomas K, Nemire R, Gable KN, et al. Curriculum in psychiatry and neurology for pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(7):5925. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8175925. DOI: 10.5688/ajpe8175925 PubMed PMID: 29109559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fincham JE. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the Journal. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):43. doi: 10.5688/aj720243. DOI: 10.5688/aj720243 PubMed PMID: 18483608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]