Abstract

A series of α-methylated analogues of the potent sRTX thiourea antagonists were investigated as rTRPV1 ligands in order to examine the effect of α-methylation on receptor activity. The SAR analysis indicated that activity was stereospecific with the (R)-configuration of the newly formed chiral center providing high binding affinity and potent antagonism while the configuration of the C-region was not significant.

Keywords: Vanilloid receptor 1, TRPV1 antagonist, Capsaicin, Resiniferatoxin

The vanilloid receptor TRPV1 has emerged as an exciting therapeutic target for a broad range on conditions, reflecting the fundamental role of the C-fiber sensory afferent neurons in which they are expressed.1 While TRPV1 was initially defined as the site of action of naturally occurring agonists such as capsaicin (CAP) or the ultrapotent resiniferatoxin (RTX), a key advance was the finding that TRPV1 antagonism could be achieved with appropriate ligands, building on the developing insights in vanilloid structure activity relations.2,3 These initial findings have fueled vigorous efforts in medicinal chemistry and in structural understanding of vanilloid-TRPV1 interactions.4–12 Because of the great potency at TRPV1 of RTX compared to CAP, one approach we have taken has been to try to retain such enhanced potency of RTX upon structural simplification.

Structurally, both CAP and RTX have a vanilloid moiety (A-region) that is connected through either ester or amide linkages (B-region) to a long alkyl chain or diterpene moiety (C-region), respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Natural and synthetic TRPV1 agonists.

The synthetic surrogates 1 and 2 were designed to mimic the principal pharmacophores of capsaicin and resiniferatoxin, respectively, and proved to be potent agonists in the rat and human TRPV1/CHO systems.13 The 3-pivaloyloxy-2-benzylpropyl group, which represents the C-region of 2, was derived from the key pharmacophores of the diterpene in RTX in an effort to capture the markedly higher binding affinity to TRPV1 of RTX relative to that of capsaicin.

We have previously reported that isosteric replacement of the phenolic hydroxyl group in the A-region of the potent agonists 1 and 2 with the methylsulfonamido group provided the potent antagonists 3 and 5, respectively, which inhibited the activation by capsaicin of rat and human TRPV1 expressed in CHO cells (Fig. 2).14,15 The SAR investigation of the B-region of 3 indicated that compound 4, the α-methyl substituted analogue of 3, showed similar potency to that of 3 but displayed enhanced binding to the receptor with stereospecificity for the (R)-configuration.16

Figure 2.

Lead TRPV1 antagonists.

Impressively, in the amide B-region surrogates 6 and 8, α-methylation led to greater improvement in receptor potency and specificity (Fig. 2). Although compound 6 displayed moderate binding affinity and antagonism, its α-methylated analogue 7 showed an approximately 10-fold increase in receptor potency.17 Of its two chiral analogues, the (S)-configuration showed approximately a further two-fold enhancement in receptor activity compared to the corresponding racemate, whereas the (R)-configuration provided weak antagonism. In addition, the α-methylation of the simplified RTX (sRTX) amide antagonist 8 provided compound 9 as a diastereomeric mixture, which also showed a dramatic increase in receptor potency compared to 8.18 The receptor activities of the four different isomers of 9 indicated that the (S)-configuration of the α-methyl group displayed high potency irrespective of the chirality of the C-region. Modeling analysis suggested that the α-methyl in the propanamide B-region constituted an additional pharmacophore group which interacted with a small hydrophobic pocket on the receptor.18

As part of our continuing effort to examine the effect of α-methylation on potent TRPV1 ligands, we investigated the α-methylated analogues of simplified RTX thiourea antagonist 5a–c and its phenylalanol analogues. In this paper, we described the efficient syntheses of the racemic/chiral α-methylated thiourea derivatives, their receptor activities and SAR analysis.

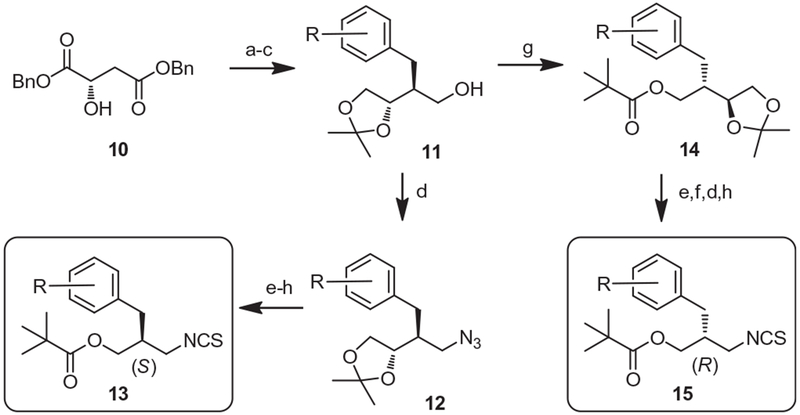

The synthesis of the chiral C-region of the target compounds was accomplished by Seebach’s diastereoselective alkylation of the α-alkoxide enolate as a key reaction (Scheme 1). Anti-selective alkylations of dibenzyl l-malate 10 with substituted benzyl bromides afforded 3R-benzyl-2S-hydroxysuccinates, which were reduced and then protected to provide the diverging intermediates 11. For the synthesis of the (S)-isomeric isothiocyanate 13, the hydroxyl group of 11 was converted into the corresponding azide 12 and then its acetonide was transformed into the 3-pivaloyloxy group in three steps. For the synthesis of the chiral (R)-isomeric isothiocyanate 15, the hydroxyl group of 11 was pivaloylated to afford 14 and then its acetonide was transformed into the corresponding isothiocyanate in four steps. The racemic C-region was prepared as described in the previous report.19

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of chiral C-region. Reagents and conditions: (a) LHMDS, ArCH2Br, HMPA, THF, 55–68%; (b) LiAlH4, THF, 55–60%; (c) pTsOH, acetone, 76–82%; (d) PPh3, DPPA, DEAD, THF, 88–90%; (e) H5IO6, ether, 98%; (f) NaBH4, MeOH, 72–89%; (g) Me3CCOCl, pyridine, 80–82%; (h) CS2, PPh3, THF, reflux, 80–90%.

The syntheses of the stereo isomeric compounds 19–30 were generally accomplished by the coupling of the corresponding C-region isothiocyanates with A-region amines (Scheme 2). For the syntheses of the racemic α-methyl A-region analogues, commercially available 4-aminoacetophenone 16 was mesylated and then its methylketone was converted into the corresponding amine via the oxime to afford 17, which was condensed with the C-region isothiocyanates to afford the α-methyl analogues 23, 24, 27 and 28. For the syntheses of the chiral α-methyl A-region analogues, commercially available optical (R or S)-α-methyl-4-nitrobenzylamine 18 were condensed with the C-region isothiocyanates, respectively, and then the 4-nitro group was converted to the corresponding 4-methylsulfonamide to afford the chiral α-methyl analogues 19–22, 25, 26, 29 and 30. As references, the chiral isomers of 5a was prepared from (4-methylsulfonylamino)benzylamine by the same method shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 3-pivaloyl-2-benzyl-propyl C-region analogues. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH3SO2Cl, pyridine, 95%; (b) NH2OH-HCl, pyridine, 85–88%; (c) H2, Pd–C, HCl, MeOH, 96–98%; (d) RNCS, CH2Cl2 or DMF, 82–93%; (e) RNCS, NEt3, CH2Cl2, 82–84%; (f) H2, Pd–C, MeOH, 96–98%; (g) CH3SO2Cl, pyridine, 92–94%.

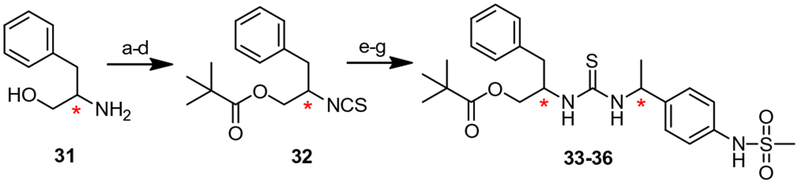

For the syntheses of phenylalanol-type chiral C-region analogues, commercially available optical (R or S)-phenylalanol 31 was transformed into the corresponding isothiocyanate 32 in four steps, respectively, which was converted to the thioureas 33–36 by following the same methods described in Scheme 2 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 2-pivaloyl-1-benzyl-ethyl C-region analogues. Reagents and conditions: (a) Boc2O, CH2Cl2, rt, 94%; (b) Me3CCOCl, NEt3, CH2Cl2,0 °C, 88%; (c) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (d) thiocarbonyldiimidazole, NEt3, DMF, 50 °C, 82%; (e) RNCS, NEt3, CH2Cl2, 82–84%; (f) H2, Pd–C, MeOH, 96–98%; (g) CH3SO2Cl, pyridine, 92–94%.

The binding affinities and potencies as agonists/antagonists of the synthesized TRPV1 ligands were assessed in vitro by a binding competition assay with [3H]RTX and by a functional 45Ca2+ uptake assay using rat TRPV1 heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, as previously described.3 The results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, together with the potencies of 5a–c as references.

Table 1.

In vitro rTRPV1 activities for 3-pivaloyloxy-2-benzylpropyl C-region analogues

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | Chirality (C1) (C2) | Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | Ki(CAP) (nM) | ||

| (R)-5a | H | R | 252 (±77) | NE | 64.3 (±9.8) | |

| (S)-5a | H | S | 236 (±4.0) | NE | 80.6 (±6.4) | |

| 19 | H | R | R | 22.7 (±4.4) | NE | 44.5 (±9.9) |

| 20 | H | R | S | 19.4 (±1.9) | NE | 89 (±20) |

| 21 | H | S | R | 1140 (±160) | NE | 3500 (±300) |

| 22 | H | S | S | 710 (±240) | NE | 133 (±24) |

| 5b | 29.3 | WE | 67 | |||

| 23 | 3,4-Me2 | 37.2 (±5.9) | NE | 25.9 (±9.1) | ||

| 24 | 3,4-Me2 | R | 6.1 (±2.3) | NE | 6.9 (±1.4) | |

| 25 | 3,4-Me2 | R | R | 15.2 (±3.4) | NE | 7.1 (±1.3) |

| 26 | 3,4-Me2 | R | S | 2.12 (±0.73) | NE | 13.2 (±5.6) |

| 5c | 64 | WE | 86 | |||

| 27 | 4-t-Bu | 42.7 (±5.6) | NE | 28.7 (±8.7) | ||

| 28 | 4-t-Bu | R | 10.0 (±1.3) | NE | 23.9 (±6.1) | |

| 29 | 4-t-Bu | R | R | 17.9 (±1.2) | NE | 53 (±11) |

| 30 | 4-t-Bu | R | S | 6.75 (±0.99) | NE | 30.6 (±7.3) |

Table 2.

In vitro rTRPV1 activities for 2-pivaloyloxy-1-benzylethyl C-region analogues

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | Ki (nM) | |

| 33 | R | R | 420 (±32) | NE | 193 (±95) |

| 34 | R | S | 272 (±28) | NE | 290 (±66) |

| 35 | S | R | NE | NE | WEa |

| 36 | S | S | NE | NE | WEa |

Only fractional antagonism: 35, 47%; 36, 4%.

First, we examined the effect of α-methylation on 5a with R = H. In the two chiral isomers of 5a, its (R)-configuration showed slightly better antagonism than that of (S)-configuration. Incorporation of α-methyl group into 5a provided the four different stereo-isomers 19–22 (C1: α-methyl, C2: C-region chiral centers), respectively. The result indicated that the α-methylation produced the stereospecific antagonism and the C1-configuration in the two chiral centers was critical for the receptor activity in which (R)-configuration of C1 (19, 20) showed much better binding affinity and antagonism than those of (S)-configuration of C1 (21,22) irrespective of C2 chirality. Compounds 19 and 20 showed approximately a 10-fold increase in binding affinity and slight or no enhancement in antagonism compared to (R)-5a and (S)-5a, respectively. The preference for the R-configuration of C1 in receptor activity was also examined in the thiourea antagonist 4 with a 4-t-butylbenzyl C-region.16 In the presence of the same C1 chirality, the receptor activity upon changing the C2-configuration gave mixed results.

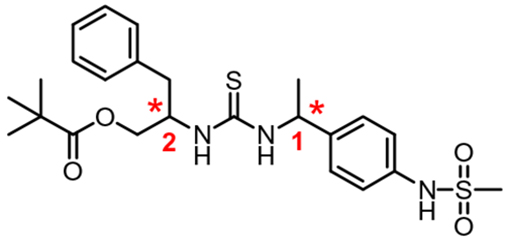

We next investigated the α-methylated analogues of 5b and 5c with R = 3,4-Me2 and 4-t-Bu, respectively, which were found to be the most potent antagonists in this series.14 Since the R-configuration of C1 in the series of the α-methylated 5a proved to be the active one, we examined only the (R)-configuration of C1 of the α-methylated 5b and 5c. As examined above, α-methylation of 5b and 5c also provided stereospecific antagonism in which the (R)-isomers 24 and 28 in the α-methyl analogues of 5b and 5c showed 5- and 6-fold increases in binding affinity and 10- and 4-fold increases in antagonism, compared to 5b and 5c, respectively. The C2-configuration in 24 and 28 also appeared not to be significant for receptor activity (25 vs 26, 29 vs 30). We previously demonstrated a similar SAR pattern in the amide B-region surrogate of 27–30 in which the receptor activity resided only in the (S)-configuration of C1 while the C2-configuration was not critical for receptor activity.18 Nevertheless, among this series, the (R,S)-configuration of C1 and C2 seemed to be the optimal configuration in which compounds 26 and 30 showed high binding affinities with Ki = 2.12 nM and 6.75 nM, respectively.

We also investigated the α-methylated thiourea analogues with a 2-pivaloyloxy-1-benzylethyl C-region (Table 2). Similar to the above, the receptor activity in this series resided only in the (R)-isomers of C1, 33 and 34, while the C2-configuration did not have a significant effect on activity.

In summary, we have investigated a series of α-methylated analogues of the potent sRTX thiourea antagonists 5a–c. The SAR analysis indicated that they showed stereospecific antagonism dependent on the α-methyl configuration, with the (R)-configuration proving to be the active one as had been found for the previous thiourea antagonists 3 and 4. In addition, the C2-configuration in the C-region appeared not to be significant for activity. Overall, we concluded that α-methylation at the benzylic position of 4-methylsulfonamidophenyl antagonists provided stereospecific and potent antagonists. Whereas the amide B-region analogues preferred the (S)-configuration for receptor activity, the thiourea B-region ones favored the (R)-configuration.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (R11-2007-107-02001-0), and by the Intramural Research Program of NIH, Center for Cancer Research, NCI (Project Z1A BC 005270).

References and notes

- 1.Szallasi A; Blumberg PM Pharmacol. Rev 1999, 51, 159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevan S; Hothi S; Hughes G;James IF; Rang HP; Shah K; Walpole CS; Yeats JC Br.J. Pharmacol 1992, 107, 544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y; Szabo T; Welter JD; Toth A; Tran R; Lee J; Kang SU; Suh YG; Blumberg PM; Lee J Mol. Pharmacol 2002, 62, 947 (erratum in Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63, 958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kym PR; Kort ME; Hutchins CW Biochem. Pharmacol 2009, 78, 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong GY; Gavva NR Brain Res. Rev 2009, 60, 267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunthorpe MJ; Chizh BA Drug Discovery Today 2009, 14, 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazar J; Gharat L; Khairathkar-Joshi N; Blumberg PM;Szallasi A Exp. Opin. Drug Disc 2009, 4, 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voight EA; Kort ME Exp. Opin. Ther. Pat 2010, 20, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szolcsányi J; Sándor Z Trend Pharmacol. Sci 2012, 33, 646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szallasi A; Sheta M Exp. Opin. Investig. Drug 2012,21,1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH; Lee Y; Ryu H; Kang DW; Lee J; Lazar J; Pearce LV; Pavlyukovets VA; Blumberg PM; Choi SJ Comput. Aided Mol. Des 2011,25, 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao M; Cao E; Julius D; Cheng Y Nature 2013, 504, 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MS; Ki Y; Ahn SY; Yoon S; Kim S-E; Park H-G; Sun W; Son K; Cui M; Choi S; Pearce LV; Esch TE; DeAndrea-Lazarus IA; Blumberg PM; Lee J Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24, 382 and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J; Lee J; Kang M; Shin M-Y; Kim J-M; Kang S-U; Lim J-O; Choi H-K; Suh Y-G; Park H-G; Oh U; Kim H-D; Park Y-H; Ha H-J; Kim Y-H; Toth A; Wang Y; Tran R; Pearce LV; Lundberg DJ; Blumberg PM J. Med. Chem 2003, 46,3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J; Kang S-U; Lim J-O; Choi H-K; Jin M-K; Toth A; Pearce LV; Tran R; Wang Y; Szabo T; Blumberg PM Bioorg. Med. Chem 2004, 12, 371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung J-U; Kim SY; Lim J-O; Choi H-K; Kang S-U; Yoon H-S; Ryu H; Kang DW; Lee J; Kang B; Choi S; Toth A; Pearce LV; Pavlyukovets VA; Lundberg DJ; Blumberg PM Bioorg. Med. Chem 2007, 15, 6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YS; Kil M-J; Kang S-U; Ryu H; Kim MS; Cho Y; Bhondwe RS; Thorat SA; Sun W; Liu K; Lee JH; Choi S; Pearce LV; Pavlyukovets VA; Morgan MA; Tran R; Lazar J; Blumberg PM; Lee J Bioorg. Med. Chem 2012, 20,215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu H; Jin M-K; Kang S-U; Kim SY; Kang DW; Lee J; Pearce LV; Pavlyukovets VA; Morgan MA; Tran R; Toth A; Lundberg DJ; Blumberg PM J. Med. Chem 2008, 51, 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J; Lee J; Kim J; Kim SY; Chun MW; Cho H; Hwang SW; Oh U; Park YH; Marquez VE; Beheshti M; Szabo T; Blumberg PM Bioorg. Med. Chem 2001, 9, 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]