Abstract

Advances in computer-assisted linguistic research have been greatly influential in reshaping linguistic research. With the increasing availability of interconnected datasets created and curated by researchers, more and more interwoven questions can now be investigated. Such advances, however, are bringing high requirements in terms of rigorousness for preparing and curating datasets. Here we present CLICS, a Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications (CLICS). CLICS tackles interconnected interdisciplinary research questions about the colexification of words across semantic categories in the world’s languages, and show-cases best practices for preparing data for cross-linguistic research. This is done by addressing shortcomings of an earlier version of the database, CLICS2, and by supplying an updated version with CLICS3, which massively increases the size and scope of the project. We provide tools and guidelines for this purpose and discuss insights resulting from organizing student tasks for database updates.

Subject terms: Databases, Sociology

| Measurement(s) | Meaning • word |

| Technology Type(s) | digital curation • computational modeling technique • Semantics |

| Factor Type(s) | source data • language |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.11317625

Background & Summary

The quantitative turn in historical linguistics and linguistic typology has dramatically changed how scholars create, use, and share linguistic information. Along with the growing amount of digitally available data for the world’s languages, we find a substantial increase in the application of new quantitative techniques. While most of the new methods are inspired by neighboring disciplines and general-purpose frameworks, such as evolutionary biology1,2, machine learning3,4, or statistical modeling5,6, the particularities of cross-linguistic data often necessitate a specific treatment of materials (reflected in recent standardization efforts7,8) and methods (illustrated by the development of new algorithms tackling specifically linguistic problems9,10).

The increased application of quantitative approaches in linguistics becomes particularly clear in semantically oriented studies on lexical typology, which investigate how languages distribute meanings across their vocabularies. Although questions concerning such categorizations across human languages have a long-standing tradition in linguistics and philosophy11,12, global-scale studies have long been restricted to certain recurrent semantic fields, such as color terms13,14, kinship terms15,16, and numeral systems17, involving smaller amounts of data with lower coverage of linguistic diversity in terms of families and geographic areas.

Along with improved techniques in data creation and curation, advanced computational methods have opened new possibilities for research in this area. One example is the Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications, first published in 201418, which offers a framework for the computer-assisted collection, computation, and exploration of worldwide patterns of cross-linguistic “colexifications”. The term colexification19 refers to instances where the same word expresses two or more comparable concepts20,21, such as in the common case of wood and tree “colexifying” in languages like Russian (both expressed by the word dérevo) or Nahuatl (both kw awi-t). By harvesting colexifications across multiple languages, with recurring patterns potentially reflecting universal aspects of human perception and cognition, researchers can identify cross-linguistic polysemies without resorting to intuitive decisions about the motivation for such identities.

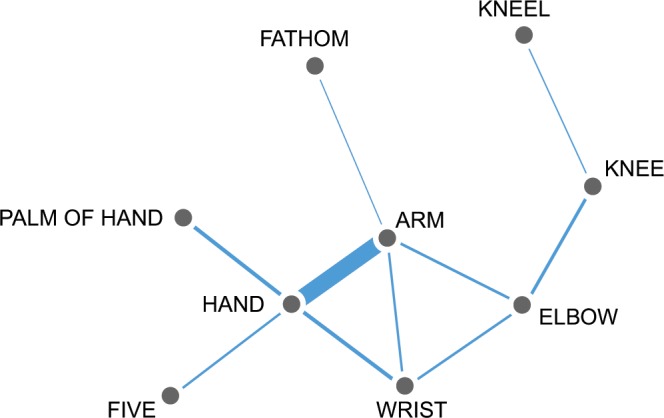

The CLICS project reflects the rigorous and transparent approaches to standardization and aggregation of linguistic data, allowing to investigate colexifications through global and areal semantic networks, as in the example of Fig. 1, mostly by reusing data first collected for historical linguistics. We designed its framework, along with the corresponding interfaces, to facilitate the exploration and testing of alleged cross-linguistic polysemies22 and areal patterns23–25. The project is becoming a popular tool not only for examining cross-linguistic patterns, particularly those involving unrelated languages, but also for conducting new research in fields not strictly related to semantically oriented lexical typology26–30 in its relation to semantic typology31–33.

Fig. 1.

Example of a colexification network. A strong link between ARM and HAND is shown, showing that in many languages both concepts are expressed with the same word; among others, weaker links between concepts HAND and FIVE, explainable by the number of fingers on a hand, and ELBOW and KNEE, explainable as both being joints, can also be observed.

A second version of the CLICS database was published in 2018, revising and greatly increasing the amount of cross-linguistic data34. These improvements were made possible by an enhanced strategy of data aggregation, relying on the standardization efforts of the Cross-Linguistic Data Formats initiative (CLDF)7, which provides standards, tools, and best practice examples for promoting linguistic data which is FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable35. By adopting these principles and coding independently published cross-linguistic datasets according to the specifications recommended by the CLDF initiative, it was possible to increase the amount of languages from less than 300 to over 2000, while expanding the number of concepts in the study from 1200 to almost 3000.

A specific shortcoming of this second release of CLICS was that, despite being based on CLDF format specifications, it did not specify how data conforming to such standards could be created in the first place. Thus, while the CLDF data underlying CLICS2 are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, the procedures involving their creation and expansion were not necessarily easy to apply due to a lack of transparency.

In order to tackle this problem, we have developed guidelines and software tools that help converting existing linguistic datasets into the CLDF format. We tested the suitability of our new curation framework by conducting two student tasks in which students with a background in linguistics helped us to convert and integrate data from different sources into our database. We illustrate the efficiency of this workflow by providing an updated version of our data, which increases the number of languages from 1220 to 3156 and the number of concepts from 2487 to 2906. In addition, we also increased and enhanced the transparency, flexibility, and reproducibility of the workflow by which CLDF datasets are analyzed and published within the CLICS framework, by publishing a testable virtual container36 that can be freely used on-line in the form of a Code Ocean capsule37.

Methods

Create and curate data in CLDF

The CLDF initiative promotes principles, tools, and workflows to make data cross-linguistically compatible and comparable, facilitating interoperability without strictly enforcing it or requiring linguists to abandon their long-standing data management conventions and expectations. Key aspects of the data format advanced by the initiative are an exhaustive and principled use of reference catalogs, such as Glottolog38 for languages and Concepticon39 for comparative concepts, along with standardization efforts like the Cross-Linguistic Transcription Systems (CLTS) for normalizing phonological transcriptions8,40.

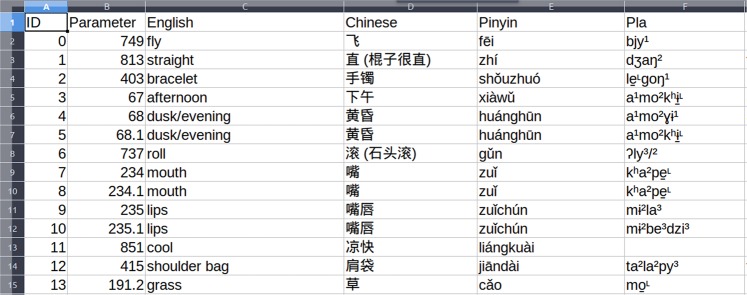

Preparing data for CLICS starts with obtaining and expanding raw data, often in the form of Excel tables (or similar formats) as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Raw data as a starting point for applying the data curation workflow. The table shows a screenshot of a snippet from the source of the yanglalo dataset.

By using our sets of tools, data can be enriched, cleaned, improved, and made ready for usage in multiple different applications, both current ones, such as CLICS, or future ones, using compliant data.

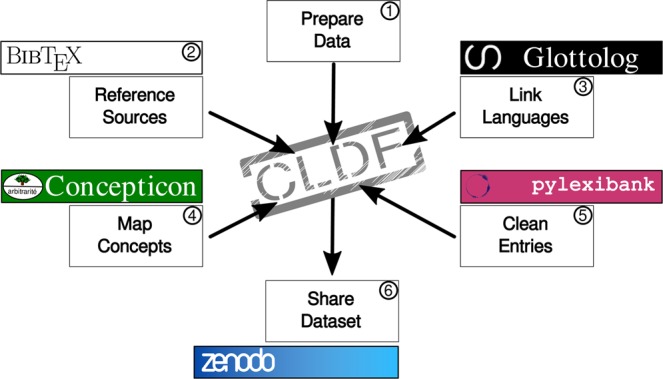

This toolbox of components supports the creation and release of CLDF datasets through an integrated workflow comprising six fundamental steps (as illustrated in Fig. 3). First, (1) scripts prepare raw data from sources for digital processing, leading the way to the subsequent catalog cross-referencing at the core of CLDF. This task includes the steps of (2) referencing sources in the BibTeX format, (3) linking languages to Glottolog, and (4) mapping concepts to Concepticon. To guarantee straightforward processing of lexical entries by CLICS and other systems, the workflow might also include a step for (5) cleaning lexical entries of systematic errors and artifacts from data conversion. Once the data have been curated and the scripts for workflow reproducibility are completed, the dataset is ready for (6) public release as a package relying on the pylexibank library, a step that includes publishing the CLDF data on Zenodo and obtaining a DOI.

Fig. 3.

A diagram representing the six fundamental steps of a CLDF dataset preparation workflow.

The first step in this workflow, preparing source data for digital processing (1), varies according to the characteristics of each dataset. The procedure ranges from the digitization of data collections only available as book scans or even fieldwork notes (using software for optical character recognition or manual labor, as done for the beidasinitic dataset41 derived from42), via the re-arrangement of data distributed in word processing or spreadsheet formats such as docx and xlsx (as for the castrosui dataset43, derived from44), up to extracting data from websites (as done for diacl45, derived from46). In many cases, scholars helped us by sharing fieldwork data (such as yanglalo47, derived from48, and bodtkhobwa49, derived from50), or providing the unpublished data underlying a previous publication (e.g. satterthwaitetb51, derived from52). In other cases, we profited from the digitization efforts of large documentation projects such as STEDT53 (the source of the suntb54 dataset, originally derived from55), and Northeuralex56,57.

In the second step, we identify all relevant sources used to create a specific dataset and store them in BibTeX format, the standard for bibliographic entries required by CLDF (2). We do this on a per-entry level, guaranteeing that for each data point it will always be possible to identify the original source; the pylexibank library will dutifully list all rows missing bibliographic references, treating them as incomplete entries. Given the large amount of bibliographic entries from language resources provided by aggregators like Glottolog38, this step is usually straightforward, although it may require more effort when the original dataset does not properly reference its sources.

The third and fourth steps comprise linking language varieties and concepts used in a dataset to the Glottolog (3) and the Concepticon catalogs (4), respectively. Both such references are curated on publicly accessible GitHub repositories, allowing researchers easy access to the entire catalog, and enabling them to request changes and additions. In both cases, on-line interfaces are available for open consultation. While these linking tasks require some linguistic expertise, such as for distinguishing the language varieties involved in a study, both projects provide libraries and tools for semi-automatic mapping that facilitate and speed up the tasks. For example, the mapping of concepts was tedious in the past when the entries in the published concept lists differed too much from proper glosses, such as when part-of-speech information was included along with the actual meaning or translation, often requiring a meticulous comparison between the published work and the corresponding concept lists. However, the second version of Concepticon58 introduced new methods for semi-automatic concept mapping through the pyconcepticon package, which can be invoked from the command-line, as well as a lookup-tool allowing to search concepts by fuzzy matching of elicitation glosses. Depending on the size of a concept list, this step can still take several hours, but the lookup procedure has been improved in the last version, because of the increasing number of concepts and concept lists.

In a fifth step, we use the pylexibank API to clean and standardize lexical entries, and remove systematic errors (5). This API allows users to convert data in raw format – when bibliographic references, links to Glottolog, and mappings to Concepticon are provided – to proper CLDF datasets. Given that linguistic datasets are often inconsistent regarding lexical form rendering, the programming interface is used to automatically clean the entries by (a) splitting multiple synonyms from their original value into unique forms each, (b) deleting brackets, comments, and other parts of the entry which do not reflect the original word form, but authors’ and compilers’ comments, (c) making a list of entries to ignore or correct, in case the automatic routine does not capture all idiosyncrasies, and (d) using explicit mapping procedures for converting from orthographies to phonological transcriptions. The resulting CLDF dataset contains both the original and unchanged textual information, labeled Value, and its processed version, labeled Form, explicitly informing what is taken from the original source and what results from our manipulations, always allowing to compare the original and curated state of the data. Even when the original is clearly erroneous, for example due to misspellings, the Value is left unchanged and we only correct the information in the Form.

As a final step, CLDF datasets are publicly released (6). The datasets live as individual Git repositories on GitHub that can be anonymously accessed and cloned. A dataset package contains all the code and data resources required to recreate the CLDF data locally, as well as interfaces for easily installing and accessing the data in any Python environment. Packages can be frozen and released on platforms like Zenodo, supplying them with persistent identifiers and archiving for reuse and data provenance. The datasets for CLICS3, for example, are aggregated within the CLICS Zenodo community (https://zenodo.org/communities/clics/, accessed on November 15, 2019).

Besides the transparency in line with the best practices for open access and reproducible research, the improvements to the CLICS project show the efficiency of this workflow and of the underlying initiative. The first version18 was based on only four datasets publicly available at the time of its development. The project was well received and reviewed, particularly due to the release of its aggregated data in an open and reusable format, but as a cross-linguistic project it suffered from several shortcomings in terms of data coverage, being heavily biased towards European and South-East Asian languages. The second version of CLICS34 combined 15 different datasets already in CLDF format, making data reuse much easier, while also increasing quality and coverage of the data. The new version doubles the number of datasets without particular needs for changes in CLICS itself. The project is fully integrated with Lexibank and with the CLDF libraries, and, as a result, when a new dataset is published, it can be installed to any local CLICS setup which, if instructed to rebuild its database, will incorporate the new information in all future analyses. Likewise, it is easy to restrict experiments by loading only a selected subset of the installed datasets. The rationale behind this workflow is shared by similar projects in related fields (e.g. computational linguistics), where data and code are to be strictly separated, allowing researchers to test different approaches and experimental setups with little effort.

Colexification analysis with CLICS

CLICS is distributed as a standard Python package comprising the pyclics programming library and the clics command-line utility. Both the library and the utility require a CLICS-specific lexical database; the recommended way of creating one is through the load function: calling clics load from the command-line prompt will create a local SQLite database for the package and populate it with data from the installed Lexibank datasets. While this allows researchers with specific needs to select and manually install the datasets they intend, for most use cases we recommend using the curated list of datasets distributed along with the project and found in the clicsthree/datasets.txt file. The list follows the structure of standard requirements.txt files and the entire set can be installed with the standard pip utility.

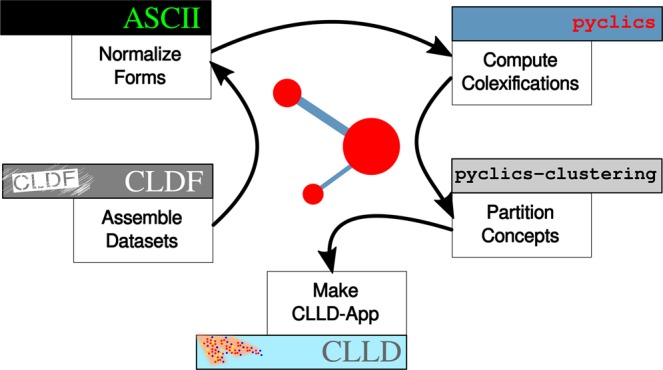

The installation of the CLICS tools is the first step in the workflow for conducting colexification analyses. The following points describe the additional steps, and the entire workflow is illustrated in the diagram of Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

A diagram representing the workflow for installing, preparing, and using CLICS.

First, we assemble a set of CLDF datasets into a CLICS database. Once the database has been generated, a colexification graph can be computed. As already described when introducing CLICS18 and CLICS234, a colexification graph is an undirected graph in which nodes represent comparable concepts and edges express the colexification weight between the concepts they link: for example, wood and tree, two concepts that as already mentioned colexify in many languages, will have a high edge weight, while water and dog, two concepts without a single instance of lexical identity in our data, will have an edge weight of zero.

Second, we normalize all forms in the database. Normalized forms are forms reduced to more basic and comparable versions by additional operations of string processing, removing information such as morpheme boundaries or diacritics, eventually converting the forms from their Unicode characters to the closest ASCII approximation by the unidecode library59.

Third, colexifications are then computed by taking the combination of all comparable concepts found in the data and, for each language variety, comparing for equality the cleaned forms that express both concepts (the comparison might involve over two words, as it is common for sources to list synonyms). Information on the colexification for each concept pair is collected both in terms of languages and language families, given that patterns found across different language families are more likely to be a polysemy stemming from human cognition than patterns because of vertical transmission or random resemblance. Cases of horizontal transmission (“borrowings”) might confound the clustering algorithms to be applied in the next stage, but our experience has shown that colexifications are actually a useful tool for identifying candidates of horizontal transmission and areal features. Once the number of matches has been collected, edge weights are adjusted according to user-specified parameters, for which we provide sensible defaults.

The output of running CLICS3 with default parameters, reporting the most common colexifications and their counts for the number of language families, languages, and words, is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The twenty most common colexifications for CLICS3, as the output of command clics colexifications.

| Concept A | Concept B | Families | Languages | Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOOD | TREE | 59 | 348 | 361 |

| MOON | MONTH | 57 | 324 | 327 |

| FINGERNAIL | CLAW | 55 | 236 | 243 |

| LEG | FOOT | 52 | 349 | 358 |

| KNIFE (FOR EATING) | KNIFE | 51 | 268 | 282 |

| SON-IN-LAW (OF MAN) | SON-IN-LAW (OF WOMAN) | 49 | 261 | 280 |

| SKIN | BARK | 49 | 209 | 213 |

| WORD | LANGUAGE | 49 | 148 | 149 |

| ARM | HAND | 48 | 294 | 300 |

| LISTEN | HEAR | 48 | 107 | 109 |

| MEAT | FLESH | 47 | 252 | 262 |

| DAUGHTER-IN-LAW (OF WOMAN) | DAUGHTER-IN-LAW (OF MAN) | 47 | 234 | 256 |

| SKIN | LEATHER | 46 | 236 | 258 |

| BLUE | GREEN | 46 | 195 | 204 |

| MALE (OF ANIMAL) | MALE (OF PERSON) | 45 | 145 | 163 |

| WOMAN | WIFE | 44 | 289 | 301 |

| DISH | PLATE | 44 | 155 | 170 |

| FEMALE (OF PERSON) | FEMALE (OF ANIMAL) | 44 | 146 | 154 |

| EARTH (SOIL) | LAND | 43 | 159 | 167 |

| PATH | ROAD | 43 | 133 | 153 |

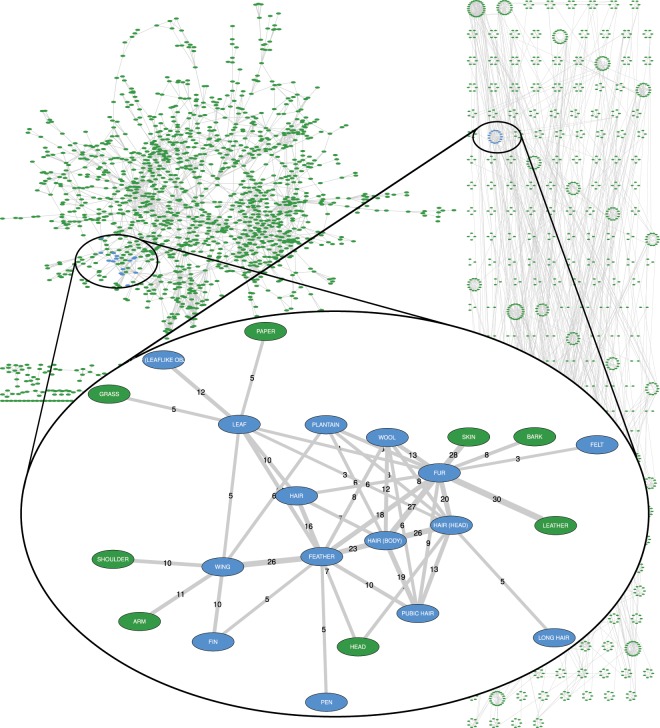

Finally, the graph data generated by the colexification computation, along with the statistics on the score of each colexification and the number of families, languages, and words involved, can be used in different quantitative analyses, e.g. clustering algorithms to partition the graph in “subgraphs” or “communities”. A sample output created with infomap clustering and a family threshold of 3 is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Colexification clusters in CLICS3.

Our experience with CLICS confirms that, as in most real-world networks and particularly in social ones, nodes from colexification studies are not evenly distributed, but concentrate in groups of relatively high density that can be identified by the most adopted methods60,61 and even by manual inspection: while some nodes might be part of two or more communities, the clusters detected by the clustering of colexification networks are usually quite distinct one from the other62,63. These can be called “semantic communities”, as they tend to be linked in terms of semantic proximity, establishing relationships that, in most cases, linguists have described as acceptable or even expected, with one or more central nodes acting as “centers of gravity” for the cluster: one example is the network already shown in Fig. 1, oriented towards the anatomy of human limbs and centered on the strong arm-hand colexification.

CLICS tools provide different clustering methods (see Section Usage-notes) that allow to identify clusters for automatic or manual exploration, especially when using its graphical interface. Both methods not only identify the semantic communities but also collect complementary information allowing to give each one an appropriate label related to the semantic centers of the subgraph.

The command-line utility can perform clustering through its cluster command followed by the name of the algorithm to use (a list of the algorithms is provided by the clics cluster list command). For example, clics cluster infomap will cluster the graph with the infomap algorithm64, in which community structure is detected with random walks (with a community mathematically defined as a group of nodes with more internal than external connecting edges). After clustering, we can obtain additional summary statistics with the clics graph-stats command: for standard CLICS3 with default parameters (and the seed 42 to fix the randomness of the random walk approach) and clustering with the recommended and default infomap algorithm, the process results in 1647 nodes, 2960 edges, 92 components, and 249 communities.

The data generated by following the workflow outlined in 4 can be used in multiple different ways (see Section Usage-notes), e.g. for preparing a web-based representation of the computed data using the CLLD65 toolkit.

Data Records

CLICS3 is distributed with 30 different datasets, as detailed in Table 2, of which half were added for this new release. Most datasets were originally collected for purpose of language documentation and historical linguistics, such as bodtkhobwa49 (derived from50), while a few were generated from existing lexical collections, such as logos66 (derived from18), or from previous linguistic studies, as in the case of wold67 (derived from68). We selected datasets for inclusion either due to interest for historical linguistics, to maximize the coverage of CLICS2 in terms of linguistic families and areas, or because of on-going collaborations with the authors of the studies.

Table 2.

Datasets included in CLICS3, along with individual counts for glosses (“Glosses”), concepts mapped to Concepticon (“Concepts”), language varieties (“Varieties”), language varieties mapped to Glottolog (“Glottocodes”), and language families (“Families”); new datasets included for the CLICS3 release are also indicated. Each dataset was published as an independent work on Zenodo, as per the respective citations.

| Dataset | Source | Glosses | Concepticon | Varieties | Glottocodes | Families | New | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | abrahammonpa84 | 85 | 304 | 304 | 30 | 16 | 2 | Yes |

| 2 | allenbai86 | 87 | 499 | 499 | 9 | 9 | 1 | |

| 3 | bantubvd88 | 89 | 420 | 415 | 10 | 10 | 1 | |

| 4 | beidasinitic41 | 42 | 736 | 735 | 18 | 18 | 1 | |

| 5 | bodtkhobwa49 | 50 | 553 | 536 | 8 | 8 | 1 | Yes |

| 6 | bowernpny90 | 91 | 338 | 338 | 175 | 172 | 1 | |

| 7 | castrosui43 | 44 | 510 | 508 | 16 | 3 | 1 | Yes |

| 8 | chenhmongmien92 | 93 | 793 | 793 | 22 | 20 | 1 | Yes |

| 9 | diacl45 | 46 | 537 | 537 | 371 | 351 | 25 | Yes |

| 10 | halenepal69 | 70 | 699 | 662 | 13 | 13 | 2 | Yes |

| 11 | hantganbangime94 | 95 | 299 | 299 | 22 | 22 | 5 | Yes |

| 12 | hubercolumbian96 | 97 | 346 | 345 | 69 | 65 | 16 | |

| 13 | ids98 | 99 | 1310 | 1308 | 320 | 275 | 60 | |

| 14 | kraftchadic100 | 101 | 433 | 428 | 66 | 59 | 2 | |

| 15 | lexirumah102 | 103 | 604 | 602 | 357 | 231 | 12 | Yes |

| 16 | logos66 | 18 | 707 | 707 | 5 | 5 | 1 | Yes |

| 17 | marrisonnaga71 | 72 | 580 | 572 | 40 | 39 | 1 | Yes |

| 18 | mitterhoferbena73 | 74 | 342 | 335 | 13 | 13 | 1 | Yes |

| 19 | naganorgyalrongic104 | 105 | 969 | 877 | 10 | 8 | 1 | Yes |

| 20 | northeuralex56 | 57 | 952 | 951 | 107 | 107 | 21 | |

| 21 | robinsonap106 | 107 | 391 | 391 | 13 | 13 | 1 | |

| 22 | satterthwaitetb51 | 52 | 418 | 418 | 18 | 18 | 1 | |

| 23 | sohartmannchin108 | 109 | 279 | 279 | 8 | 7 | 1 | Yes |

| 24 | suntb54 | 55 | 929 | 929 | 49 | 49 | 1 | |

| 25 | tls110 | 111 | 1140 | 811 | 126 | 107 | 1 | |

| 26 | transnewguineaorg112 | 113 | 904 | 865 | 1004 | 760 | 106 | Yes |

| 27 | tryonsolomon114 | 115 | 317 | 314 | 111 | 96 | 5 | |

| 28 | wold67 | 68 | 1459 | 1458 | 41 | 41 | 24 | |

| 29 | yanglalo47 | 48 | 875 | 869 | 7 | 7 | 1 | Yes |

| 30 | zgraggenmadang116 | 117 | 311 | 310 | 98 | 98 | 1 | |

| TOTAL | 2906 | 3156 | 2271 | 200 |

Technical Validation

To investigate to which degree our enhanced workflows would improve the efficiency of data creation and curation within the CLDF framework, we conducted two tests. First, we tested the workflow ourselves by actively searching for new datasets which could be added to our framework, noting improvements that could be made for third-party usage and public release. Second, we organized two student tasks with the goal of adding new datasets to CLICS, both involving the delegation of parts of the workflow to students of Linguistics. In the following paragraphs, we will quickly discuss our experiences with these tasks, besides presenting some detailed information on the notable differences between CLICS2 and the improved CLICS3 resulting from both tests.

Workflow validation

In order to validate the claims of improved reproducibility and the general validity of the workflow for preparing, adding, and analyzing new datasets, we conducted two student tasks in which participants at graduate and undergraduate level were asked to contribute to CLICS3 by using the tools we developed. The first student task was carried out as part of a seminar for doctoral students on Semantics in Contact, taught by M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (MKT) as part of a summer school of the Societas Linguistica Europaea (August 2018, University of Tartu). The second task was carried out as part of an M.A. level course on Methods in Linguistic Typology, taught by V. Gast (VG) as a regular seminar at the Friedrich Schiller University (Jena) in the winter semester of 2018/2019.

MKT’s group was first introduced to CLICS2, to the website accompanying the CLICS project, and to the general ideas behind a colexification database. This helped to shape a better understanding of what is curated in the context of CLICS. In a second step, we provided a task description tailored for the students, which was presented by MKT. In a shortened format, it comprised (1) general requirements for CLICS datasets (as described in previous sections), (2) steps for digitizing and preparing data tables (raw input processing), (3) Concepticon linking (aided by semi-automatic mapping), (4) Glottolog linking (identifying languages with Glottocodes), (5) providing bibliographic information with BibTeX, (6) providing provenance information and verbal descriptions of the data.

The students were split into five groups of two people, and each group was tasked with carrying out one of the six tasks for a specific dataset we provided. The students were not given strict deadlines, but we informed them that they would be listed as contributors to the next update of the CLICS2 database if they provided the data up to two months after we introduced the task to them. While the students were working on their respective tasks, we provided additional help by answering specific questions, such as regarding the detailed mapping of certain concepts to Concepticon, via email.

All student groups finished their tasks successfully, with only minor corrections and email interactions from our side. The processed data provided by the students lead to the inclusion of five new datasets to CLICS3: castrosui43, a collection of Sui dialects of the Tai-Kadai family spoken in Southern China derived from44, halenepal69, a large collection of languages from Nepal derived from70, marrisonnaga71, a collection of Naga languages (a branch of the Sino-Tibetan family) derived from72, yanglalo47, a dataset of regional varieties of Lalo (a Loloish language cluster spoken in Yunnan, part of the Sino-Tibetan family) derived from48, and mitterhoferbena73, a collection of Bena dialects spoken in Tanzania derived from74.

A similar approach was taken by VG and his group of students, with special emphasis being placed on the difficulties and advantages of a process for collaborative and distributed data preparation. They received instruction material similar to that of MKT’s group, but more nuanced towards the dataset they were asked to work with, namely diacl45, a collection of linguistic data from 26 large language families all over the world derived from46. Pre-processed data was provided by us and special attention was paid to the process of concept mapping.

In summary, the outcome of the workflow proposed was positive for both groups, and the data produced by the students and their supervisors helped us immensely with extending CLICS3. Some students pointed us to problems in our software pipeline, such as missing documentation on dependencies in our installation instructions. They also indicated difficulties during the process of concept mapping, such as problems arising from insufficient concept definitions for linking elicitation glosses to concept sets. We have addressed most of these problems and hope to obtain more feedback from future users in order to further enhance our workflows.

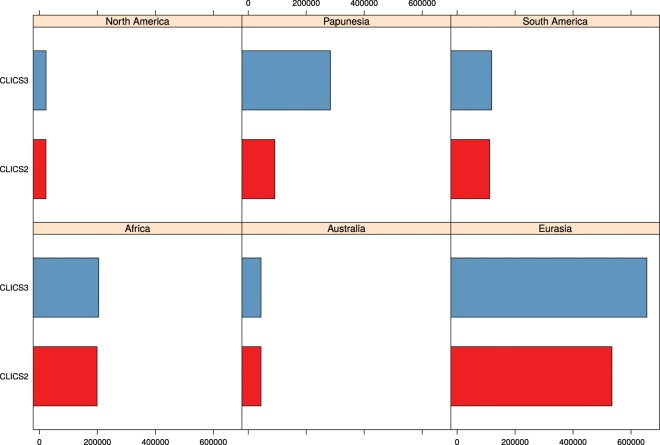

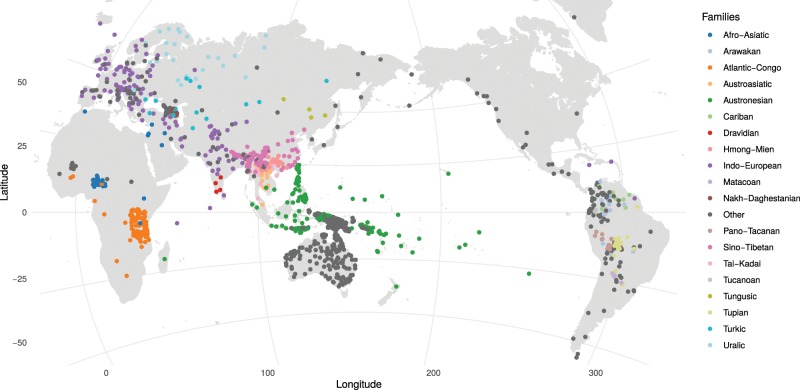

CLICS3 validation

The technical validation of CLICS3 is based on functions for deconstructing forms and consequences of this for mapping and finding colexifications. If we compare the data status of CLICS2 with the amount of data available with the release of CLICS3, we can see a substantial increase in data, both regarding the number of languages being covered by CLICS3, and the total number of concepts now included. When looking at the detailed comparisons in Fig. 6, however, we can see that the additions of data occurred in different regions of the world. While we note a major increase of data points in Papunesia, a point of importance for better coverage of “hot spots”75, and a moderate increase in Eurasia, the data is unchanged in Africa, North America, and Australia, and has only slightly increased in South America. As can be easily seen from Fig. 7, Africa and North America are still only sparsely covered in CLICS3. Future work should try to target these regions specifically.

Fig. 6.

Increase in data points (values) for CLICS3.

Fig. 7.

Distribution of language varieties in CLICS3.

While this shows, beyond doubt, that our data aggregation strategy based on transparent workflows that create FAIR data was, by and large, successful, it is important to note that the average mutual coverage, which is defined as the average number of concepts for which two languages share a translation34,76, is rather low. This, however, is not surprising, given that the original datasets were collected for different purposes. While low or skewed coverage of concepts is not a problem for CLICS, which is still mostly used as a tool for the manual inspection of colexifications, it should be made very clear that quantitative approaches dealing with CLICS2 and CLICS3 need to control explicitly for missing data.

Usage Notes

The CLICS pipeline produces several artifacts that can serve as an entry point for researchers: a locally browsable interface, well-suited for exploratory research, a SQLite database containing all data points, languoids and additional information, and colexification clusters in the Graph Modelling Language (GML77).

The SQLite database can easily be processed with programming languages like R and Python, while the GML representation of CLICS colexification graphs is fully compatible with tools for advanced network analyses, e.g. Cytoscape78. Researchers have the choice between different clustering algorithms (currently supported and implemented: highly connected subgraphs79, infomap or map equation64, Louvain modularity80, hierarchical clustering81, label propagation82, and connected component clustering83) and can easily plug-in and experiment with different clustering techniques using a custom package (https://github.com/clics/pyclics-clustering, accessed on November 13, 2019). A sample workflow is also illustrated in the Code Ocean capsule for this publication37. For easier accessibility, CLICS data can also be accessed on the web with our CLICS CLLD app, available at https://clics.clld.org/ (accessed on November 15, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the generous support by many institutes and funding agencies. TT, MSW, NES, YL, and JML were funded by the the ERC Starting Grant 715618 Computer-Assisted Language Comparison (http://calc.digling.org). SJG was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project number DE 120101954) and the ARC Center of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language grant (CE140100041). MKT was supported by the Riksbankens Jubileums Fond (Grant SAB17-0588:1). TB was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, P2BEP1_181779, “Reconstruction of Proto-Western Kho-Bwa”. We are also very grateful for the help and data provided by many researchers, among them: Cathryn Yang fordata on Lolo languages47, Andy Castro fordata on Sui dialects43, Michael Cysouw for help with the digitization of41,97,101, Claire Bowern fordata on Pama-Nyungan91, Gerd Carling fordata from the Diachronic Atlas of Comparative Linguistics project45, Doug Cooper fordata on Miao and Yao languages93, and the STEDT project for providing digital versions of the data underlying70,72,105.

Author contributions

R.F., J.M.L., C.R., T.T. and S.J.G. initialized the study. C.R., J.M.L. and T.T. wrote the first draft. S.J.G., R.F. and R.D.G. revised the first draft. C.R., J.M.L., M.S.W., N.M., N.E.S., R.F., S.J.G. and T.T. provided datasets in CLDF format and helped with data curation. C.R., J.M.L., R.F., S.J.G. and T.T. developed software for the CLICS pipeline. R.F. wrote the code for the CLLD application. A.H., G.K., T.B. and S.C. contributed data. M.K.T., C.R. and J.M.L. conducted student task 1, V.G., C.R. and J.M.L. conducted student task 2. B.V.E., E.K., H.A., M.P., N.H. and S.P. participated in student task 1, C.H., K.P., I.B., S.M. and S.R. participated in student task 2. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Code availability

The workflow by which CLDF datasets are analyzed and published within the CLICS framework, is available as a testable virtual container36 that can be freely used on-line in the form of a Code Ocean capsule37.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Christoph Rzymski, Email: rzymski@shh.mpg.de.

Tiago Tresoldi, Email: tresoldi@shh.mpg.de.

Johann-Mattis List, Email: list@shh.mpg.de.

References

- 1.Atkinson QD, Gray RD. Curious parallels and curious connections: Phylogenetic thinking in biology and historical linguistics. Systematic Biol. 2005;54:513–526. doi: 10.1080/10635150590950317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.List J-M, Pathmanathan JS, Lopez P, Bapteste E. Unity and disunity in evolutionary sciences: process-based analogies open common research avenues for biology and linguistics. Biol. Direct. 2016;11:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13062-016-0145-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rama, T. Siamese convolutional networks for cognate identification. In Proceedings of COLING 2016, the 26th International Conference onComputational Linguistics: Technical Papers, 1018–1027 (Association for Comp. Linguist., 2016).

- 4.Rama, T. & List, J.-M. An automated framework for fast cognate detection and bayesian phylogenetic inference in computational historical linguistics. In 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 6225–6235 (Association for Comp. Linguist., 2019).

- 5.Blasi DE, Wichmann S, Hammarström H, Stadler P, Christiansen MH. Sound-meaning association biases evidenced across thousands of languages. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:10818–10823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605782113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromham L, Hua X, Fitzpatrick TG, Greenhill SJ. Rate of language evolution is affected by population size. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2097–2102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419704112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forkel R, et al. Cross-Linguistic Data Formats, advancing data sharing and re-use in comparative linguistics. Sci. Data. 2018;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson C, et al. A cross-linguistic database of phonetic transcription systems. Yearbook of the Poznan Linguistic Meeting. 2018;4:21–53. doi: 10.2478/yplm-2018-0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.List, J.-M. Sequence comparison in historical linguistics (Düsseldorf University Press, Düsseldorf, 2014).

- 10.List J-M. Automatic inference of sound correspondence patterns across multiple languages. Comput. Linguist. 2019;1:137–161. doi: 10.1162/coli_a_00344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bach, E. W. & Chao, W. On semantic universals and typology. In Christiansen, M. H., Collins, C. & Edelman, S. (eds.) Language Universals, 152–173 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009).

- 12.Evans, N. Semantic typology. In Sung, J. J. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of linguistic typology, 504–533 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011).

- 13.Berlin, B. & Kay, P. Basic color terms: Their universality and evolution (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1969).

- 14.Kay P, McDaniel CK. The linguistic significance of the meanings of basic color terms. Language. 1978;72:522–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nerlove S, Romney AK. Sibling terminology and cross-sex behavior. Am. Anthropol. 1967;69:179–87. doi: 10.1525/aa.1967.69.2.02a00050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murdock GP. Kin term patterns and their distribution. Ethnology. 1970;9:165–208. doi: 10.2307/3772782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg, J. H. Generalizations about numeral systems. In Greenberg, J. H. (ed.) Universals of human language. Word Structure, 249–95 (Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1978).

- 18.List J-M, Mayer T, Terhalle A, Urban M. 2014. CLICS database of crosslinguistic colexifications. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 19.François Alexandre. Studies in Language Companion Series. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2008. Semantic maps and the typology of colexification: Intertwining polysemous networks across languages; pp. 163–215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haspelmath M. Comparative concepts and descriptive categories. Language. 2010;86:663–687. doi: 10.1353/lan.2010.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.List J-M, 2019. Concepticon 2.2, a resource for the linking of concept lists. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 22.Urban M. Asymmetries in overt marking and directionality in semantic change. J. Hist. Linguist. 2011;1:3–47. doi: 10.1075/jhl.1.1.02urb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. & Liljegren, H. Lexical semantics and areal linguistics. In Hickey, R. (ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of areal linguistics, 204–236 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017).

- 24.Gast, V. & Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. The areal factor in lexical typology: some evidence from lexical databases. In Olmen, D. V., Mortelmans, T. & Brisard, F. (eds.) Aspects of linguistic variation, 43–81 (de Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, 2018).

- 25.Schapper, A., Roque, L. S. & Hendery, R. Tree, firewood and fire in the languages of Sahul. In Juvonen, P. & Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. (eds.) The lexical typology of semantic shifts, 355–422 (De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin and Boston, 2016).

- 26.Brochhagen, T. Improving coordination on novel meaning through context and semantic structure. In Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Cognitive Aspects of Computational Language Learning, 74–82 (Association for Comp. Linguist., 2015).

- 27.Divjak D, Levshina N, Klavan J. Cognitive linguistics: Looking back, looking forward. Cogn. Linguist. 2016;27:447–463. doi: 10.1515/cog-2016-0095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil D. Roon ve, DO/GIVE coexpression, and language contact in Northwest New Guinea. Nusa: linguistic studies of Indonesian and other languages in Indonesia. 2017;62:43–100. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Georgakopoulos T, Polis S. The semantic map model: State of the art and future avenues for linguistic research. Lang. Linguist. Compass. 2018;12:e12270. doi: 10.1111/lnc3.12270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.San Roque L, Kendrick KH, Norcliffe E, Majid A. Universal meaning extensions of perception verbs are grounded in interaction. Cogn. Linguist. 2018;29:371–406. doi: 10.1515/cog-2017-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koptjevskaja-Tamm Maria. Studies in Language Companion Series. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2008. Approaching lexical typology; pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. Semantic typology. In Dabrowska, E. & Divjak, D. (eds.) Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics, 453–472 (de Gruyter Mouton, Berlin and New York, 2015).

- 33.Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M., Rakhilin, E. & Vanhove, M. The semantics of lexical typology. In Riemer, N. (ed.) Routledge Handbook of Semantics, 434–454 (Routledge, London, 2016).

- 34.List J-M, et al. CLICS-2: An improved Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications assembling lexical data with the help of Cross-Linguistic Data Formats. Linguist. Typol. 2018;22:277–306. doi: 10.1515/lingty-2018-0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Merkel D. Docker: Lightweight linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux. Journal. 2014;2014:2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rzymski, C., Tresoldi, T., Greenhill, S. J., Forkel, R. & List, J.-M. CLICS 3: Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications. version 2. Code Ocean, 10.24433/CO.4564348.v2 (2019).

- 38.Hammarström H, Haspelmath M, Forkel R. 2019. Glottolog. Version 4.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 39.List, J.-M., Cysouw, M. & Forkel, R. Concepticon. A resource for the linking of concept lists. In Calzolari, N. et al. (eds.) Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, 2393–2400 (European Language Resources Association, 2016).

- 40.List J-M, 2019. Cross-Linguistic Transcription Systems. Version 1.3.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 41.List J-M. 2019. lexibank/beidasinitic: Chinese Dialect Vocabularies. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 42.Beijing University (ed.) Hányû fāngyán cíhuì [Chinese dialect vocabularies] (Wénzì Gˇaigé, Beijing, 1964).

- 43.List J-M, Rzymski C, Wu M-S. 2019. lexibank/castrosui: Sui Dialect Research. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 44.Castro, A. & Pan, X. Sui dialect research (SIL International, Dallas, 2015).

- 45.Forkel R, Rzymski C, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/diacl: Diachronic Atlas of Comparative Linguistics. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 46.Carling G, et al. Diachronic Atlas of Comparative Linguistics (DiACL). A database for ancient language typology. Plos One. 2019;e0205313:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/yanglalo: Lalo Regional Varieties. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 48.Yang, C. Lalo regional varieties: Phylogeny, dialectometry and sociolinguistics. PhD dissertation, La Trobe University, Bundoora (2011).

- 49.List J-M, Wu M-S, Forkel R, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/bodtkhobwa: Lexical Cognates in Western Kho-Bwa. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 50.Bodt TA, List J-M. Testing the predictive strength of the comparative method: An ongoing experiment on unattested words in Western Kho-Bwa langauges. Pap. Hist. Phonol. 2019;4:22–44. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tresoldi T, List J-M, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/satterthwaitetb: Phylogenetic Inference of the Tibeto-Burman Languages. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 52.Satterthwaite-Phillips, D. Phylogenetic inference of the Tibeto-Burman languages or on the usefuseful of lexicostatistics (and “megalo”-comparison) for the subgrouping of Tibeto-Burman. PhD dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford (2011).

- 53.Matisoff, J. A. The Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus project (University of California, Berkeley, 2015).

- 54.List J-M, Forkel R, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/suntb: Tibeto-Burman Phonology and Lexicon. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 55.Sun, H. (ed.) Zàngmiănyûyû yīn hé cíhuì [Tibeto-Burman phonology and lexicon] (Chinese Social Sciences Press, Beijing, 1991).

- 56.Tresoldi T, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/northeuralex: NorthEuraLex. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 57.Dellert, J. & Jäger, G. (eds.) NorthEuraLex (Eberhard-Karls University Tübingen, Tübingen, 2017).

- 58.List JM, 2019. Concepticon. A resource for the linking of concept lists. Version 2.2.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 59.Solc, T. & Burke, S. M. Unidecode - ASCII transliterations of Unicode text, https://pypi.org/project/Unidecode/1.1.1/ (2019).

- 60.Fortunato S, Hric D. Community detection in networks: A user guide. Phys. Rep. 2016;659:1–44. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2016.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Emmons S, Kobourov S, Gallant M, Börner K. Analysis of network clustering algorithms and cluster quality metrics at scale. Plos One. 2016;11:e0159161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holland PW, Leinhardt S. Transitivity in structural models of small groups. Comp. Group Stud. 1971;2:107–124. doi: 10.1177/104649647100200201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newman, M. E. J. Networks. An Introduction (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010).

- 64.Rosvall M, Bergstrom CT. Maps of random walks on complex networks reveal community structure. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1118–1123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706851105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Forkel, R. & Bank, S. CLLD: A toolkit for Cross-Linguistic Databases. Version 5.0 (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena), 10.5281/zenodo.3437148 (2019).

- 66.List J-M, Rzymski C. 2019. lexibank/logos: Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications (Version 1.0). Zenodo. [DOI]

- 67.Forkel R, Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/wold: The World Loanword Database. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 68.Haspelmath, M. & Tadmor, U. (eds.) Loanwords in the world’s languages (de Gruyter, Berlin and New York, 2009).

- 69.Rzymski C, List J-M, Morozova N. 2019. lexibank/halenepal: Wordlists in Selected Languages of Nepal. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 70.Hale, A. Clause, sentence, and discourse patterns in selected languages of Nepal (Summer Institute of Linguistics and Tribhuvan University Press, Kathmandu, 1973).

- 71.Wu M-S, List J-M, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/marrisonnaga: Naga Languages of North-East India. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 72.Marrison, G. E. The classification of the Naga languages of North-East India. In Matisoff, J. (ed.) STEDT database (University of California, Berkeley), http://stedt.berkeley.edu/~stedt-cgi/rootcanal.pl/source/GEM-CNL (2015).

- 73.Rzymski C, Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/mitterhoferbena: Bena Dialect Survey. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 74.Mitterhofer, B. Lessons from a dialect survey of Bena: Analyzing wordlists (SIL International, 2013).

- 75.Hua X, Greenhill SJ, Cardillo M, Schneemann H, Bromham L. The ecological drivers of variation in global language diversity. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07882-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rama, T., List, J.-M., Wahle, J. & Jäger, G. Are automatic methods for cognate detection good enough for phylogenetic reconstruction in historical linguistics? In Proceedings of the North American Chapter of the Association of Computational Linguistics, 393–400 (Association for Comp. Linguist., 2018).

- 77.Himsolt, M. GML: A portable graph file format. Tech. Rep., Universität Passau (1997).

- 78.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hartuv E, Shamir R. A clustering algorithm based on graph connectivity. Inform. Process. Lett. 2000;76:175–181. doi: 10.1016/S0020-0190(00)00142-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blondel VD, Guillaume J-L, Lambiotte R, Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech.–Theory E. 2008;2008:P10008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhu, X. & Ghahramani, Z. Learning from labeled and unlabeled data with label propagation. Tech. Rep., Carnegie Mellon University (2002).

- 83.Hopcroft J, Tarjan R. Algorithm 447: Efficient algorithms for graph manipulation. Commun. ACM. 1973;16:372–378. doi: 10.1145/362248.362272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lai Y, Wu M-S, List J-M, Schweikhard N. 2019. lexibank/abrahammonpa: Sociolinguistic Research on Monpa. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 85.Abraham, B., Sako, K., Kinny, E. & Zeliang, I. Sociolinguistic Research among Selected Groups in Western Arunachal Pradesh: Highlighting Monpa. (SIL International, Dallas, 2005).

- 86.Forkel R, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/allenbai: Bai Dialect Survey. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 87.Allen, B. Bai Dialect Survey (SIL International, Dallas, 2007).

- 88.Forkel R, Greenhill SJ. 2019. lexibank/bantubvd: Bantu Basic Vocabulary Database. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 89.Greenhill, S. J. & Gray, R. Bantu basic vocabulary database. (Auckland University, Auckland, 2015).

- 90.Forkel R, Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/bowernpny: The Internal Structure of Pama-Nyungan. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 91.Bowern C, Atkinson QD. Computational phylogenetics of the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan. Language. 2012;88:817–845. doi: 10.1353/lan.2012.0081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.List J-M, Wu M-S. 2019. lexibank/chenhmongmien: Miao and Yao Language. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 93.Chén, Q. Miáoyáo yûwén [Miao and Yao language] (China Minzu University Press, Beijing, 2012).

- 94.List J-M, Hantgan A. 2019. lingpy/language-island-paper: Bangime and Friends. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 95.Hantgan, A. & List, J.-M. Bangime. secret language, language isolate, or language island? Journal of Language Contact (forthcoming).

- 96.List J-M, Forkel R, Rzymski C. 2019. lexibank/hubercolumbian: Comparative Vocabulary. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 97.Huber, R. Q. & Reed, R. B. Vocabulario comparativo: palabras selectas de lenguas indígenas de Colombia [Comparative vocabulary. Selected words from the indigeneous languages of Columbia] (Asociación Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, Santafé de Bogotá, 1992).

- 98.Forkel R, Rzymski C. 2019. lexibank/ids: Intercontinental Dictionary Series. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 99.Key, M. R. & Comrie, B. The intercontinental dictionary series (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, 2016).

- 100.Forkel R, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/kraftchadic: Chadic Wordlists. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 101.Kraft, C. H. Chadic wordlists (Dietrich Reimer, Berlin, 1981).

- 102.Edwards O, Kaiping GA, Klamer M. 2019. LexiRumah v3.0.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 103.Kaiping GA, Klamer M. Lexirumah: An online lexical database of the lesser sunda islands. Plos One. 2018;13:1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tresoldi T, Forkel R, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/naganorgyalrongic: rGyalrongic Languages Database. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 105.Nagano, Y. & Prins, M. rGyalrongic languages database. In STEDT database (University of California, Berkeley), https://stedt.berkeley.edu/~stedt-cgi/rootcanal.pl/source/YN-RGLD (2013).

- 106.Forkel R, Greenhill SJ, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/robinsonap: Internal Classification of the Alor-Pantar Language Family. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 107.Robinson LC, Holton G. Internal classification of the Alor-Pantar language family using computational methods applied to the lexicon. Language Dynamics and Change. 2012;2:123–149. doi: 10.1163/22105832-20120201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.List J-M. 2019. lexibank/sohartmannchin: Notes on the Southern Chin Languages. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 109.So-Hartmann H. Notes on the Southern Chin languages. LTBA. 1988;11:98–119. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tresoldi T, Forkel R, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/tls: Tanzania Language Survey. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 111.Nurse, D. & Phillipson, G. Tanzania Language Survey (Department of Foreign Languages and Linguistics, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam, 1975).

- 112.Greenhill SJ. 2019. lexibank/transnewguineaorg: TransNewGuinea.org. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 113.Greenhill SJ. Transnewguinea.org: an online database of New Guinea languages. Plos One. 2015;10:e0141563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Greenhill SJ, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/tryonsolomon: Solomon Islands Languages. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 115.Tryon, D. T. & Hackman, B. D. Solomon islands languages. An internal classification. No. 72 (Pacific Linguistics, Canberra, 1983).

- 116.Forkel R, Greenhill SJ, List J-M, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/zgraggenmadang: Madang Comparative Wordlists. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 117.Z’graggen, J. A. A comparative word list of the Northern Adelbert Range languages, Madang Province, Papua New Guinea (Pacific Linguistics, Canberra, 1980).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- List J-M, Mayer T, Terhalle A, Urban M. 2014. CLICS database of crosslinguistic colexifications. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, 2019. Concepticon 2.2, a resource for the linking of concept lists. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Hammarström H, Haspelmath M, Forkel R. 2019. Glottolog. Version 4.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, 2019. Cross-Linguistic Transcription Systems. Version 1.3.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M. 2019. lexibank/beidasinitic: Chinese Dialect Vocabularies. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Rzymski C, Wu M-S. 2019. lexibank/castrosui: Sui Dialect Research. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Rzymski C, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/diacl: Diachronic Atlas of Comparative Linguistics. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/yanglalo: Lalo Regional Varieties. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Wu M-S, Forkel R, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/bodtkhobwa: Lexical Cognates in Western Kho-Bwa. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Tresoldi T, List J-M, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/satterthwaitetb: Phylogenetic Inference of the Tibeto-Burman Languages. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Forkel R, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/suntb: Tibeto-Burman Phonology and Lexicon. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Tresoldi T, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/northeuralex: NorthEuraLex. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List JM, 2019. Concepticon. A resource for the linking of concept lists. Version 2.2.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Rzymski C. 2019. lexibank/logos: Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications (Version 1.0). Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/wold: The World Loanword Database. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Rzymski C, List J-M, Morozova N. 2019. lexibank/halenepal: Wordlists in Selected Languages of Nepal. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Wu M-S, List J-M, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/marrisonnaga: Naga Languages of North-East India. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Rzymski C, Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/mitterhoferbena: Bena Dialect Survey. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Lai Y, Wu M-S, List J-M, Schweikhard N. 2019. lexibank/abrahammonpa: Sociolinguistic Research on Monpa. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/allenbai: Bai Dialect Survey. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Greenhill SJ. 2019. lexibank/bantubvd: Bantu Basic Vocabulary Database. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Tresoldi T, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/bowernpny: The Internal Structure of Pama-Nyungan. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Wu M-S. 2019. lexibank/chenhmongmien: Miao and Yao Language. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Hantgan A. 2019. lingpy/language-island-paper: Bangime and Friends. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M, Forkel R, Rzymski C. 2019. lexibank/hubercolumbian: Comparative Vocabulary. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Rzymski C. 2019. lexibank/ids: Intercontinental Dictionary Series. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/kraftchadic: Chadic Wordlists. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Edwards O, Kaiping GA, Klamer M. 2019. LexiRumah v3.0.0. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Tresoldi T, Forkel R, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/naganorgyalrongic: rGyalrongic Languages Database. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Greenhill SJ, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/robinsonap: Internal Classification of the Alor-Pantar Language Family. Zenodo. [DOI]

- List J-M. 2019. lexibank/sohartmannchin: Notes on the Southern Chin Languages. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Tresoldi T, Forkel R, List J-M. 2019. lexibank/tls: Tanzania Language Survey. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Greenhill SJ. 2019. lexibank/transnewguineaorg: TransNewGuinea.org. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Greenhill SJ, Forkel R. 2019. lexibank/tryonsolomon: Solomon Islands Languages. Zenodo. [DOI]

- Forkel R, Greenhill SJ, List J-M, Tresoldi T. 2019. lexibank/zgraggenmadang: Madang Comparative Wordlists. Zenodo. [DOI]

Data Availability Statement

The workflow by which CLDF datasets are analyzed and published within the CLICS framework, is available as a testable virtual container36 that can be freely used on-line in the form of a Code Ocean capsule37.