Abstract

Objectives

The use of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in differentiation between benign and malignant adnexal masses in children and adolescents might be of great value in the diagnostic workup of sonographically indeterminate masses, since preserving fertility is of particular importance in this population. This systematic review evaluates the diagnostic value of MR imaging in children with an ovarian mass.

Methods

The review was made according to the PRISMA Statement. PubMed and EMBASE were systematically searched for studies on the use of MR imaging in differential diagnosis of ovarian masses in both adult women and children from 2008 to 2018.

Results

Sixteen paediatric and 18 adult studies were included. In the included studies, MR imaging has shown good diagnostic performance in differentiating between benign and malignant ovarian masses. MR imaging techniques including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging seem to further improve the diagnostic performance.

Conclusion

The addition of DWI with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values measured in enhancing components of solid lesions and DCE imaging may further increase the good diagnostic performance of MR imaging in the pre-operative differentiation between benign and malignant ovarian masses by increasing specificity. Prospective age-specific studies are needed to confirm the high diagnostic performance of MR imaging in children and adolescents with a sonographically indeterminate ovarian mass.

Key Points

• MR imaging, based on several morphological features, is of good diagnostic performance in differentiating between benign and malignant ovarian masses. Sensitivity and specificity varied between 84.8 to 100% and 20.0 to 98.4%, respectively.

• MR imaging techniques like diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging seem to improve the diagnostic performance.

• Specific studies in children and adolescents with ovarian masses are required to confirm the suggested increased diagnostic performance of DWI and DCE in this population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00330-019-06420-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ovarian neoplasms, Magnetic resonance imaging, Systematic review

Introduction

Ovarian malignancies in children and adolescents are relatively rare, with an incidence of 3 per 100,000 compared with 56 cases per 100,000 at the age of 65 to 69 years [1–3]. Despite this low incidence, ovarian tumours constitute the most common gynaecological malignancy in children and adolescents. Paediatric ovarian masses encompass a variety of benign and malignant tumours, including rare types such as sex cord-stromal tumours [4–6]. Both this heterogeneity and the importance of fertility preservation in this age group make the diagnostic assessment of these masses challenging.

While malignant ovarian neoplasms may need a more aggressive surgical approach, benign masses can either be safely monitored or undergo simple resection allowing for a fertility- and ovary-sparing approach [7]. Being able to discriminate between benign and malignant masses of the ovary is therefore of considerable clinical importance in the initial surgical management [4, 8]. Ultrasound is the first imaging modality in the diagnostic assessment of ovarian masses at any age. Clinically useful rules have been established by the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) group to differentiate between benign and malignant masses. Nevertheless, in about one-fifth of the cases, the nature of the ovarian mass remains undefined [9].

In case of sonographically indeterminate ovarian masses, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging can provide additional information, e.g. on the different components of the mass, tumour rupture and peritoneal depositions. Figures 1 and 2 show examples of an immature teratoma grade I (treated as a benign tumour with local resection and follow-up) and a malignant yolk sac tumour. Functional imaging techniques like diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging could be of additional value [10]. DCE enables qualitative, quantitative or semi-quantitative evaluation of tumour vascularity, thereby providing information about the nature of the mass. This investigation is based on enhancement patterns, expressed as time-intensity curves (TICs), of which three different types are acknowledged. Type I displays a gradual, continuous rise in signal intensity; type II shows a moderate rise in signal intensity followed by a plateau; and type III is characterised as early washout [11, 12]. In adults, several studies have evaluated the diagnostic value of MR imaging in differentiating between malignant and benign neoplasms and characterising the specific nature of ovarian masses. Based on these studies, the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) has developed an algorithmic approach for the imaging of the sonographically indeterminate adnexal mass [7, 13–16]. However, data on the role of MR imaging in discriminating between benign and malignant ovarian masses in children is scarce. In this systematic review, we evaluate the diagnostic value of MR imaging in children and adolescents with an ovarian mass, including the value of additional MR techniques.

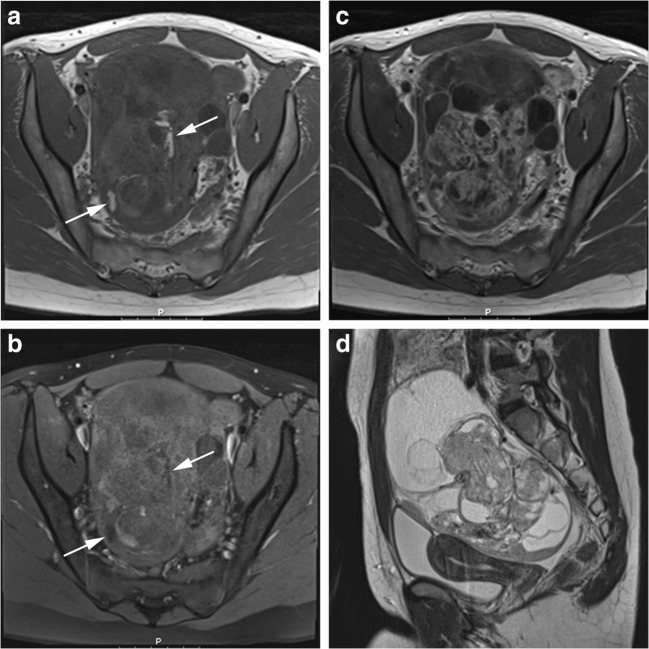

Fig. 1.

An example of immature teratoma grade 1 of the right ovary in a 15-year-old girl, treated as a benign tumour with local resection and follow-up. Axial T1-weighted before and after administration of gadolinium contrast (a, c), axial T1-weighted with fat-suppression (b) and sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo (d) show a cystic-solid mass with fatty components (arrows). Intralesional fat is diagnostic for a teratoma. The relative large amount of enhancing parts increases the risk of immature components

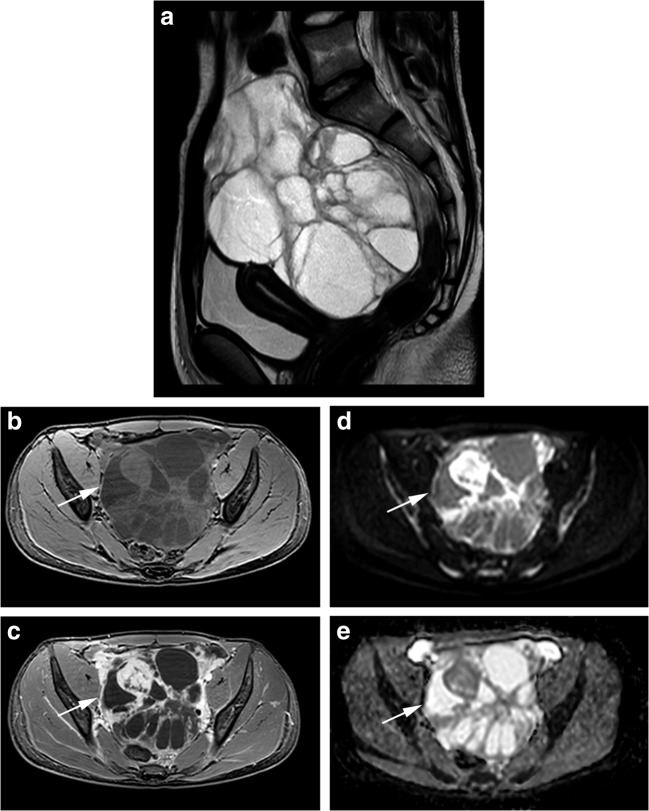

Fig. 2.

An example of yolk sac tumour of the right ovary in a 16-year-old girl. Sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo TSE (a) and T1-weighted gradient echo with fat suppression before and after administration of gadolinium contrast (b, c) show a large cystic solid mass in the lower abdomen. The enhancing parts of the lesion show relative impeded diffusion (arrow) at axial DWI (b1000 and ADC map; d,e)

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

This review is written according to the PRISMA Statement [17]. A thorough search of PubMed and EMBASE for all available literature published from 2008 to 2018 was performed. These libraries were systematically searched for original studies on the use of MR imaging in differential diagnosis of ovarian masses in both adult women and children. We classified studies into two groups. Studies were classified as ‘paediatric’, when the age of all included patients was 18 years or less. Studies performed on adult women, on the other hand, were classified as ‘adult’. The full search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Articles were included if suspected ovarian masses were evaluated with MR imaging (either 1.5 T or 3.0 T), including the evaluation of contrast enhancement, and were compared with a histopathology reference standard. Studies providing no description of MR imaging findings and studies on adult women that analysed selectively benign, borderline or malignant masses were excluded. However, similar studies as well as case reports performed on paediatric patients were included, in order to minimise the risk of missing relevant studies. Since ovarian carcinomas are very rare in children, only studies performed on adult patients that included more than 20% of malignant tumours other than carcinoma were considered relevant for this review. This particular cut-off was chosen pragmatically, since it was expected most MR studies in adult ovarian tumours focus on epithelial neoplasms, due to its prevalence of 80–90%.

All studies resulting from the literature search were assessed independently by two researchers (A.M., L.N.). Disagreements about study inclusion or exclusion were settled by consensus.

Quality assessment

The quality of the individual studies was judged using the “Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy 2015” (STARD 2015) checklist [18]. Included studies were further assessed for methodologic quality independently by two researchers (A.M., L.N.), using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence Classification rubric [19].

Data extraction

From the included studies, population size expressed as the number of ovarian masses analysed, mean age of the participating patients, histopathological classification of the ovarian masses and MR imaging protocol and analysis, as well as MR imaging features of the concerning ovarian masses, were scored. As for MR imaging features, information about the following parameters were extracted: size, shape, boundary, wall and septum thickness, vegetation, mass configuration, bilaterality, signal intensity of T1-weighted imaging, ascites/pelvic fluid, peritoneal implants/nodules and contrast enhancement. If available, information on b-values used in DWI and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values were collected. Concerning semi-quantitative DCE, data on TICs, enhancement amplitude and time to peak were included. Lastly, data on diagnostic performance expressed as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) or area under the curve (AUC) for these individual parameters were extracted when provided.

Results

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

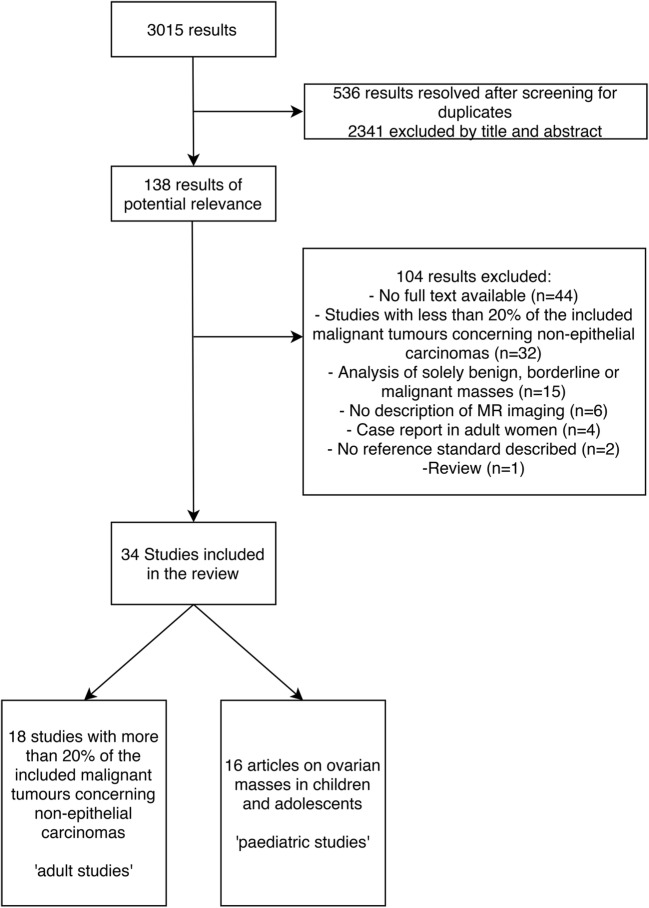

The study selection process is shown in Fig. 3. The search in PubMed and EMBASE resulted in 3015 studies, of which 536 studies turned out to be duplicates. The remaining 2479 studies were screened by title and abstract, based on which 2341 studies were excluded. Consequently, 138 articles were of potential relevance to this systematic review and their full texts were analysed. This led to the exclusion of another 104 studies. The remaining 34 studies were analysed in this review.

Fig. 3.

The flowchart summarises the search process with the number of studies included and excluded

Quality assessment

The studies in adult women were predominantly scored as Oxford Evidence level 2 (cross-sectional studies with consistently applied reference standard and blinding). Levels of evidence of the individual studies can be found in Table 1. Quality assessment of the included studies in adult women, using the STARD 2015, is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review regarding the use of MR imaging in differential diagnosis of ovarian masses

| Study (reference) | Oxford level | n | Mean age in years | Histopathological classification of included ovarian masses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult studies | ||||

| Li et al 2017 [11] | 2 | 102 | 57 (benign), 37 (borderline), 54 (malignant) | Benign (n = 15), borderline (n = 16), malignant (n = 71) |

| Li et al 2015 [12] | 3 | 48 | NA (range 11–79) | Benign (n = 13), malignant (n = 35) |

| Zhao et al 2018 [20] | 3 | 42 | 52 (benign), 41 (malignant) | Benign (n = 29), malignant (n = 13) |

| Zhang et al 2012 [21] | 2 | 139 | 52 | Cysts (n = 21), endometriomas (n = 33), benign (n = 43), malignant (n = 42) |

| Bernardin et al 2012 [22] | 2 | 67 | 48 | Benign (n = 31), malignant (n = 36) |

| Nasr et al 2014 [23] 3 | 23 | 36 (benign), 45 (malignant) | Benign (n = 12), malignant (n = 11) | |

| Takeuchi et al 2009 [24] | 2 | 49 | 59 | Benign (n = 10), borderline (n = 6), malignant (n = 33) |

| Mansour et al 2015 [25] | 2 | 235 | 39 | Benign (n = 75), malignant (n = 160) |

| Zhang et al 2012 [26] | 3 | 202 | 57 | Benign (n = 74), malignant (n = 128) |

| Tsili et al 2008 [27] | 2 | 89 | 67 | Benign (n = 66), malignant (n = 23) |

| Dilks et al 2010 [28] | 2 | 26 | 43 | Benign (n = 14), malignant (n = 12) |

| Tsuboyama et al 2014 [29] | 2 | 127 | 53 | Benign (n = 30), borderline (n = 31), malignant (n = 66) |

| Elzayat et al 2017 [30] | 3 | 32 | 39 (benign), 34 (borderline), 43 (malignant) | Benign (n = 7), borderline (n = 4), malignant (n = 21) |

| Emad-Eldin et al 2018 [31] | 2 | 65 | 44 | Benign (n = 30), borderline (n = 7), malignant (n = 28) |

| Mansour et al 2015 [32] | 2 | 150 | 29 (benign), 39 (borderline), 46 (malignant) | Benign (n = 42), borderline (n = 26), malignant (n = 82) |

| Li et al 2018 [33] | 2 | 109 | 57 (benign), 34 (borderline), 51 (malignant) | Benign (n = 15), borderline (n = 28), malignant (n = 66) |

| Zhang et al 2014 [34] | 2 | 144 | 37 years (endometric cysts), 40 years (teratomas) | Endometric cysts (n = 35), teratomas (n = 28) |

| Zhao et al 2014 [35] | 2 | 50 | 51 (benign), 41 (borderline) | Benign (n = 26), borderline (n = 24) |

| Paediatric studies | ||||

| Emil et al 2017 [36] | 3 | 18 | 15 | Benign |

| Marro et al 2016 [37] | 2 | 32 | 13 | Benign, borderline and malignant |

| Thomas et al 2012 [38] | 4 | 1 | 14 | Bilateral mucinous cystadenomas |

| Willems et al 2012 [39] | 4 | 1 | 15 | Benign mucinous cystadenoma |

| Park et al 2010 [40] | 4 | 1 | 11 | Sclerosing stromal tumour |

| Ghanbari 2013 [41] | 4 | 1 | 3 | Juvenile granulosa cell tumour |

| Tsuboyama et al 2018 [42] | 4 | 2 | 14 (1), 10 (2) | Dysgerminoma |

| Bedir et al 2014 [43] | 4 | 1 | 10 | Juvenile granulosa cell tumour |

| Boraschi et al 2008 [44] | 4 | 1 | 7 | Immature teratoma |

| Chaurasia et al 2014 [45] | 4 | 1 | 7 | Sclerosing stromal tumour |

| Lin et al 2017 [46] | 4 | 74 | 6 | Germ cell tumours |

| Pollmann et al 2017 [47] | 4 | 1 | 13 | Mature teratoma |

| Braun et al 2012 [48] | 4 | 1 | 12 | Leydig cell tumour |

| Calcaterra et al 2013 [49] | 4 | 1 | 8 | Juvenile granulosa cell tumour |

| Rogers et al 2014 [50] | 4 | 129 | 12 | Benign and malignant |

| Nejkovic et al 2012 [51] | 4 | 1 | 17 | Mature teratoma |

Characteristics of all studies included in this systematic review, including the number of ovarian masses analysed, histopathological classification hereof and mean age of the participants per concerning study. The methodologic quality of included studies based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence Classification rubric is provided as well

n = population size expressed as number of ovarian masses included in the original study

NA, not available

Since most studies in children and adolescents concerned either case reports or case series, the majority of these were scored as Oxford Evidence level 4, with the exception of two studies (one cross-sectional study, one non-consecutive study) (Table 1).

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies (18 ‘adult’ [11, 12, 20–35] and 16 ‘paediatric’ studies [36–51]) are provided in Table 1. The mean age of patients included was 10.8 years in the paediatric and 46.9 years in the adult studies. The number of ovarian lesions analysed ranged between 1 and 74 in the paediatric studies and between 23 and 235 in the adult studies. All studies analysed the use of MR imaging in differentiating between benign and malignant tumours of the ovary, with several studies incorporating the differentiation of epithelial borderline tumours as well.

Paediatric studies

Table 2 shows MR imaging findings of the sixteen studies that were included: three cohort studies and 13 case reports. All three cohort studies analysed the diagnostic performance of MR imaging in children and adolescents with ovarian masses (or ovarian germ cell tumours specifically). The thirteen case reports describe limited data on MR characteristics.

Table 2.

MR imaging descriptions of ovarian masses provided by ‘paediatric studies’

| Histopathological classification | Conventional MR imaging findings | DWI | DCE | Diagnostic performance | ||||||||||

| Original studies | ||||||||||||||

| Emil et al [36] | Benign | No report | No report | No report | Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV and accuracy of MRI in characterising adnexal lesions as neoplastic: 89%, 94%, 94%, 89% and 93%, respectively | |||||||||

| Marro et al [37] | Benign, borderline and malignant | No report | No report | No report | ‘MRI correctly suggested benign nature in 24/28 (85.7%) benign masses and was indeterminate for the nature in remaining 4 masses. MRI correctly suggested malignant nature in 3/4 malignant masses and was indeterminate in the mature teratoma with a microscopic focus of yolk sac tumour’ | |||||||||

| Lin et al [46] | Germ cell tumours | No report | No report | No report | Sensitivity of MRI of 97% | |||||||||

| Histopathological classification | Conventional MR imaging findings | DWI | DCE | |||||||||||

| Size | Walls/septa | Vegetation | Boundary | Shape | Mass configuration | Bilaterality | T2WI | Ascites | Peritoneal implants | Constrast enhancement | ||||

| Case reports | ||||||||||||||

| Thomas et al [38] | Bilateral mucinous cystadenomas |

7 × 3 × 4 cm 9 × 5 × 5 cm 16 × 8 × 18 cm |

No report | No report | Capsulated | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | Absent | No report | No report | No report |

| Willems et al [39] | Benign mucinous cystadenoma | 17.5 cm | No report | No report | Well-defined | No report | Multicystic | No report | No report | No report | Absent | Varying enhancements on FS T1WI | No report | No report |

| Park et al [40] | Sclerosing stromal tumour | 8.9 × 2.6 × 6.6 cm | No report | No report | Well-defined | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report |

| Ghanbari [41] | Juvenile granulosa cell tumour | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | Multiple cystic components | No report | No report | No report | Tumour adhesion to anterior bowel loops | No report | No report | No report |

| Tsuboyamaet al [42] | Dysgerminoma combined with gonadoblastomas | 17 cm | Fibrovascular septa | Nodules (1.5 cm) | No report | Lobulated | No report | Absent | Intermediate signal intensity | No report | No report | Strong enhancement of fibrovascular septa on FS CE T1WI | High signal intensity | No report |

| Yolk sac tumour and dysgerminomas with gonadoblastoma | ± 8 cm | No report | Nodules (5 mm) | Smooth outlined | No report | No report | Absent |

A homogeneous hyperintense area A heterogeneous mass intermediate to high signal intensity Nodules with intermediate intensity |

No report | No report | Strong enhancement of the heterogeneous area and nodules on FS CE T1WI | High signal intensity of the heterogeneous mass and nodules | No report | |

| Bedir et al [43] | Juvenile granulosa cell tumour | 76 × 87 × 75 mm | No report | No report | No report | No report | Multiple cystic and solid components | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report |

| Boraschi et al [44] | Immature teratoma | 6 × 7 × 7 cm | No report | No report | Capsulated | Round | Liquid (prevalent) and solid components (peripherally, ‘fat and a small signal void’) | Multicystic appearance of the other ovary | Iso- to hyperintensity of the solid component | Present | Absent | No report | No report | No report |

| Chaurasia et al [45] | Sclerosing stromal tumour | 10 × 9 × 5 cm | No report | No report | Well-defined | No report | Heterogeneous solid and cystic mass | Absent | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report |

| Pollmann et al [47] | Mature teratoma | 28 × 19 × 12 cm | No report | Solid vegetation with calcifications | No report | No report | Cystic | Other ovary undetectable | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report |

| Braun et al [48] | Leydig cell tumour | 8 × 13 × 12 mm | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | ‘Absorbing the contrast agent’ | No report | No report |

| Calcaterra et al [49] | Juvenile granulosa cell tumour | 13 × 13 × 7.6 cm | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report |

| Rogers et al [50] | Benign and malignant | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report | No report |

| Nejkovic et al [51] | Mature teratoma | 100 mm in diameter | No report | No report | No report | No report | Heterogeneous and cystic | Tumoural aspect of the other ovary | No report | No report | Absent | No report | No report | No report |

Summary of the findings on MR, DW and DCE imaging by both original studies and case reports on ovarian masses in children and adolescents. Histopathological classification of the concerning masses and diagnostic performance of MR imaging, if available, are provided as well

DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; DCE, dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; FS T1WI, fat suppression T1-weighted imaging; FS CE T1WI, fat suppression contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging

Adult studies

MR imaging

Ten studies provided a description of MR imaging features. The most often-described features (> 4 out of 10 studies) concerned size, thickness of walls and septa (when present), presence of vegetation, mass configuration, bilaterality, signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, presence of ascites or peritoneal implants and contrast enhancement. An increased risk of malignancy was related to increased size of the lesion, increased wall thickness, presence and increased size of vegetation, mixed cystic and solid configuration, intermediate to high intensity on T2-weighted imaging, presence of contrast enhancement and of ascites or peritoneal implants. Six of the studies performed an analysis of the diagnostic performance of MR imaging [23, 27, 29–31, 34]. Criteria predictive of malignancy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy, if provided, are depicted in Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity, depending on the criteria used, varied between 84.8 to 100% and 20.0 to 98.4%, respectively.

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of MR imaging in differential diagnosis of ovarian masses

| Study (reference) | Criteria for malignancy | Diagnostic performance of MR imaging in differentiation between | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasr et al [23] |

Wall thickness > 3 mm Solid vegetation > 1 cm Thick septa > 3 mm Areas of necrosis and breaking down |

Malignant and non-malignant | 90.9% | 58.3% | 66.7% | 87.5% | 73.9% | NA |

| Tsili et al [27] |

Primary features: • Presence of masses bilaterally • Size > 4 cm • Areas of necrosis • Partly cystic-solid mass configuration, with contrast enhancement of the solid components • Cystic or solid-cystic lesions with thick and irregular walls or septa, of thickness > 3 mm and/or papillary projections, demonstrating contrast enhancement Secondary features: • Pelvic organ or wall invasion, ascites, peritoneal metastases or lymphadenopathy • Characterised as malignant when two primary or one primary and one secondary feature present |

Malignant and non-malignant | 95.2% | 98.4% | NA | NA | 97.6% | NA |

| Tsuboyama et al [29] | Unilateral or bilateral masses with papillary projections or irregular solid portions showing intermediate intensity on T2WI | Benign and borderline/malignant | 96.9% (93.5–100) | 20.0% (5.7–34.3) | NA | NA | 78.7% (71.6–85.9) | NA |

| Benign/borderline and malignant | 84.8% (76.2–93.5) | 36.1% (24.0–48.1) | 61.4% (53.0–69.9) | |||||

| Elzayat et al [30] |

Wall thickness > 3 mm Solid vegetation > 1 cm Thick septa > 3 mm Areas of necrosis and breaking down |

Malignant and non-malignant | 92% | 57.1% | 88.4% | 66.6% | 84.4% | NA |

| Emad-Eldin et al [31] |

Wall thickness > 3 mm Solid vegetation > 1 cm Thick septa > 3 mm Areas of necrosis and breaking down |

Malignant and non-malignant | 94.3% | 90% | 91.6% | 93.1% | 92.3% | NA |

| Zhang et al [34] | Vegetation and irregular thickened septa or walls of > 3 mm and solid components. In addition, any features of peritoneal or omental disease, lymphomas and ascites were considered criteria for malignancy | Malignant and non-malignant | 92.7% (79.0–98.1) | 89.3% (81.3–94.3) | 77.6% (63.0–87.8) | 96.8% (90.4–99.2) | 90.3% (83.9–94.4) | 97.2% (94.7–99.7) |

Criteria used to assess the malignancy of ovarian masses on MR imaging and the diagnostic performance hereof, expressed as sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy and AUC, if available

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the curve; NA, not available

DWI-MR imaging

Eight studies investigated the value of DWI-MRI in the differential diagnosis of ovarian masses [20, 21, 23–26, 31, 34]. b-values (s/mm2), regions of interest (ROI) used to calculate ADC values (× 10−3 mm2/s) and diagnostic performance are shown in Table 4. Mean ADC values for benign and malignant lesions exhibited a significant overlap, with values for benign masses varying between 1.16 and 2.03 × 10−3 mm2/s, whereas the range of ADC values reported for malignant masses was 0.76 to 1.39 × 10−3 mm2/s. Three of the included studies provided information on the diagnostic performance of DWI [23, 25, 31]. Nasr et al provided diagnostic performance of DWI solely, with sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 100%, 75% and 87% respectively [23]. Emad-Eldin et al and Mansour et al demonstrated sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of DWI additional to MR imaging of 100% and 93.3%; 96.77% and 85%; and 98.46% and 82.3% respectively [25, 31]. The diagnostic performance of specific ADC cut-off values, if provided, is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Diagnostic performance of DWI-MR imaging in differential diagnosis of ovarian masses

| Study (reference) | b-values (s/mm2) used | Region of interest (ROI) | ADC values (× 10–3 mm2/s) | Diagnostic performance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Borderline | Malignant | Measure | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | AUC | |||

| Zhao et al [20] | 0 and 1000 | Solid components |

Benign SCSTs 1.343 ± 0.528* |

NA |

Malignant SCSTs 0.825 ± 0.129* |

ADC 0.838 | 61.5% | 89.5% | NA | NA | 78.1% | NA |

| Zhang et al [21] | 0 and 700 | Both cystic and solid components | Benign 2.03 ± 0.94* (1) | NA |

Malignant 1.39 ± 0.62* (1) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nasr et al [23] | 0, 300 and 600 | Both cystic and solid components | 1.864 ± 0.585 (1) | NA | 0.843 ± 0.165 (1) | DWI-MRI | 100% | 75% | 79% | 100% | 87% | NA |

| Takeuchi et al [24] | 0 and 800 | Solid components | 1.38 ± 0.30* (1) | NA | 1.03 ± 0.19* (1) |

ADC 1.15 ADC 1.0 |

74% 46% |

80% 100% |

94% 100% |

44% 32% |

NA | NA |

| Mansour et al [25] | 0, 500, 1000 and 1500 | Solid components | 1.2 ± 0.34* (1) | 1.1 ± 0.06^ (1) | 0.83 ± 0.15*^ (1) | Conventional MRI + DWI | 93.3% | 85% | 88.5% | 94.4% | 82.3% | NA |

| Zhang et al [26] | 0 and 1000 | Solid components | 1.22 ± 0.46* (1) | NA | 0.91 ± 0.20* (1) |

ADC 1.20 ADC 1.20 (when cystadenofibromas, fibrothecomas and Brenner tumours are excluded) |

66.7% 97.7% |

90.9% 90.1% |

81.4% 86.6% |

82.1% 99.1% |

NA |

0.72 0.96 |

| Emad-Eldin et al [31] | 0, 500, 1000 and 1500 | Solid components | 1.16 ± 0.44 (1) | 0.92 ± 0.38 (1) | 0.76 ± 0.23 (1) |

Conventional MRI + DWI ADC 0.95 |

100% 90.5% |

96.77% 63.4% |

97.14% 54.3% |

100% 93.3% |

98.46% 72.3% |

NA |

| Zhang et al [34] | 0 and 700 | Unclear | 2.0 ± 0.99 (1) | NA | 1.36 ± 0.63 (1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Summary of the DWI protocols, including used b-values and regions of interest, and corresponding diagnostic performance of DWI imaging in ovarian masses. ADC values of benign, borderline and malignant masses, if available, are provided as well

DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; SCST, sex cord-stromal tumour; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the curve; NA, not available

*Statistically significant difference between benign and malignant with p value < 0.05

^Statistically significant difference between borderline and malignant with p value < 0.05

(1)Mean ADC value

DCE-MR imaging

Nine studies investigated the value of DCE-MRI in the differential diagnosis of ovarian masses [11, 12, 22, 23, 25, 28, 30–32]. Data on the TICs and semi-quantitative DCE parameters are depicted in Table 5, as well as diagnostic performance of this sequence and accompanying TICs. Five of these studies divided the different ovarian masses analysed by type of TIC. Type I TICs were most frequently found in benign lesions, with 33 to 85.7% of benign masses showing type I TICs. In type III TICs, on the other hand, there appeared more characteristics of malignancy, with 57.1 to 94.3% of all malignant masses exhibiting type III TICs. Overlap between benign and malignant masses was found by Elzayat et al [30] and Mansour et al [32], with one and nine malignant masses exhibiting a type I TIC, respectively. Overlap was also demonstrated by Li et al [12], with 3 benign masses exhibiting a type III TIC. The enhancement amplitude constituted one of the semi-quantitative parameters and was expressed in various ways, including maximum relative enhancement percentage (MRE%), maximum absolute enhancement (SImax), maximum relative enhancement (SIrel) and signal intensity at 60 s after enhancement (SI60). Malignant masses generally showed an increased enhancement amplitude compared with benign or borderline masses, with some of the studies demonstrating a statistically significant difference between these groups. Time to peak constituted the other semi-quantitative parameter and was indicated by time of half rising (THR), Tmax and time to peak within 200 s after enhancement (TTP200). All studies analysing this parameter agreed on malignant masses exhibiting a shorter time to peak compared with benign masses, again in several of these studies with statistically significant difference. Four studies provided information on the diagnostic performance of DCE [23, 25, 30, 31]. Nasr et al [23] and Elzayat et al [30] provided diagnostic performance of solely DCE, with sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 60% and 80%; 91% and 100%; and 77.2% and 96%, respectively. Mansour et al [25] and Emad-Eldin et al [31] demonstrated sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of DCE in addition to MR imaging of 93.3 and 94.3; 100 and 100%; and 95% and 96.9%, respectively.

Table 5.

Diagnostic performance of DCE-MR imaging in differential diagnosis of ovarian masses

| Study (reference) | Time-signal intensity curves | Semi-quantitative parameters | Diagnostic performance | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Borderline | Malignant | Enhancement amplitude | Time to peak | Measure | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | AUC | |||||

| Benign | Borderline | Malignant | Benign | Borderline | Malignant | |||||||||||

| Li et al [11] |

Type I: 5 (33%)* Type II: 10 (67%)* Type III: 0 (0%)* |

Type I: 3 (19%)^ Type II: 9 (56%)^ Type III: 4 25%)^ |

Type I: 0 (0%)*^ Type II: 12 (17%)*^ Type III: 59 (83%)*^ |

EA 220.2 ± 90.5 |

EA 269.3 ± 70.9 |

EA 267.4 ± 86.2 |

THR 55.5 ± 15.4* |

THR 37.3 ± 15^ |

THR 32.4 ± 8.5*^ |

TIC type III as indication for malignancy | 83% | 100% | NA | NA | 86% | NA |

| Li et al [12] |

Type I: 8 (61.5%)* Type II: 2 (15.4%)* Type III: 3 (23.1%)* |

NA |

Type I: 0 (0%)* Type II: 2 (5.7%)* Type III: 33 (94.3%)* |

SI60 76.42 ± 32.82* |

NA |

SI60 129.17 ± 19.37* |

NA | NA |

TTP200 72.89 ± 22.69* |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bernardin et al [22] | NA | NA | NA |

Simax 491.2 ± 467.2* Sirel 55.4 ± 38.6* |

Simax 360.2 ± 186.2^ Sirel 38.8 ± 22.1^ |

Simax 712 ± 278.6*^ Sirel 81 ± 33.5*^ |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nasr et al [23] | NA | NA | NA |

MRE% 73 ± 22.9 |

NA |

MRE% 130 ± 27 |

Time to peak 92 ± 14.3 |

NA |

Time to peak 53 ± 14.3 |

DCE-MRI | 60% | 91% | 85% | 73.2% | 77.2% | NA |

| Mansour et al [25] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Conventional MRI + DCE-MRI | 93.3% | 100% | 100% | 92.3% | 95% | NA |

| Dilks et al [28] | NA | NA | NA |

Simax 121 ± 184* Sirel 12.8 ± 19.2* |

NA |

Simax 589 ± 249* Sirel 101 ± 166* |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Elzayat et al [30] |

Type I: 4 (57%) Type II: 3 (43%) Type III: 0 (0%) |

Type I: 2 (50%) Type II: 2 (50%) Type III: 0 (0%) |

Type I: 1 (4.8%) Type II: 8 (38.1%) Type III: 12 (57.1%) |

MRE% 89* | MRE% 115^ | MRE% 168*^ | Tmax 231* | Tmax 175 | Tmax 119* | DCE-MRI in discrimination of benign versus borderline + malignant | 80% | 100% | 100% | 58% | 96% | NA |

| Emad-Eldin et al [31] | Type I: 22 (73.3%) | Type I: 3 (42.9%) |

Type I: 0 (0%) Type II: 7 (25%) Type III: 21 (75%) |

Simax 704 ± 379.35 MRE% 76.15 ± 51.36 |

Simax 654 ± 356.3 MRE% 81.9 ± 52.29 |

Simax 1267 ± 503.5 MRE% 136.32 ± 54.8 |

Tmax 232 ± 92.58 |

Tmax 184.9 ± 53.04 |

Tmax 119 ± 43.97 |

Conventional MRI + DCE-MRI | 94.3% | 100% | 100% | 93.75% | 96.9% | NA |

| Mansour et al [32] |

Type I: 36 (85.7%) Type II: 6 (14.3%) Type III: 0 (0%) |

Type I: 8 (30.8%) Type II: 8 (30.8%) Type III: 10 (38.4%) |

Type I: 9 (11.0%) Type II: 22 (26.8%) Type III: 51 (62.2%) |

MRE% 98.5 (65–158)* |

MRE% 100 (81–124)^ |

MRE% 150.5 (144.5–222.5)*^ |

Tmax 278 (218.5–346)*# |

Tmax 222 (183.5–302)#^ |

Tmax 138.5 (78–178.5)*^ |

SER type III as indication for malignancy: DCE-MRI in discrimination of benign masses DCE-MRI in discrimination of borderline masses DCE-MRI in discrimination of malignant masses |

84.2% | 85.7% | NA | NA |

84.7% 76.2% 96.3% 77% |

NA |

Summary of the findings on and diagnostic performance of DCE imaging in ovarian masses. Both qualitative assessments by describing the time-signal intensity curves (TICs) and semi-quantitative assessments (various parameters) are demonstrated

DCE, dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging; TIC, time-signal intensity curve; EA, enhancement amplitude; SI60, signal intensity at 60 s after enhancement; Simax, maximum absolute enhancement; Sirel, maximum relative enhancement; MRE%, maximum relative enhancement percentage; THR, time of half rising; TTP200, time to peak within 200 s after enhancement; Tmax, time to maximum absolute enhancement; NA, not available

*Statistically significant difference between benign and malignant with p value < 0.05

^Statistically significant difference between borderline and malignant with p value < 0.05

#Statistically significant difference between benign and borderline with p value < 0.05

Discussion

Pre-operative discrimination between benign and malignant ovarian masses is of major importance, particularly in children and adolescents, where preserving fertility constitutes a highly important aspect of the therapeutic approach. Although data of MR imaging from paediatric patients were scarce, this review suggests that DWI, with ADC values measured in enhancing components, and semi-quantitative DCE might increase the diagnostic performance of MR imaging in the pre-operative differentiation between benign and malignant ovarian masses.

MR imaging characteristics associated with malignancy included larger size, thicker walls, presence of septa and/or vegetation within the mass, increased signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, increased contrast enhancement, ascites, peritoneal implants and bilaterality. This corresponds with reports in existing literature describing masses larger than 4 cm, with solid components demonstrating contrast enhancement or cystic lesions with vegetation > 1 cm (as profuse papillary projections), wall and septum thickness of > 3 mm and areas of necrosis as suspicious [52–54]. Diagnostic performance of MR imaging has a fairly good sensitivity for differentiating malignant from benign masses. Regarding specificity, however, there is still room for improvement.

DWI seems to improve sensitivity and specificity of MR imaging to 93.3–100% and 85–96.8%, respectively [25, 31]. The added value of ADC is less clear. Although ADC values for malignant masses were lower compared with benign tumours, a considerable overlap was found. This can partly be explained by ADC values depending strongly on the pathologies included, the b-values used and whether ADC is calculated on both solid and cystic components of the lesion, or solely solid components. Several masses of benign origin, including mature teratomas, cystic endometriosis and fibromas, might occur as false positives. These ‘complex masses’ have a more dense composition, not as a result of increased cellularity but rather as a result of the presence of keratinoid substances, products of haemoglobin degradation and dense fibres respectively [24, 25, 31]. To date, no consensus exists on which preferred b-value should be used in DWI of ovarian masses. When solely analysing the studies that focussed on ‘complex masses’ (excluding fat-containing lesions or solely cystic masses), using b-values of > 800 s/mm2 and calculating ADC on solid components of the mass, considerably less overlap in ADC values was demonstrated [20, 24–26, 31]. Mean ADC values for benign masses then varied between 1.16 and 1.38 × 10−3 mm2/s and for malignant masses between 0.76 and 1.03 × 10−3 mm2/s. DWI should be performed as an additional sequence in assessing non-fatty, non-haemorrhagic ovarian masses, with ADC values only measured in enhancing components of solid lesions, preferably with the highest b-value of > 800 s/mm2 [7]. Additionally, our results suggest an ADC cut-off of 1.1 × 10−3 mm2/s might represent the best cut-off to help discriminate between benign and malignant lesions.

Another sequence that might contribute to the specificity of MR imaging is based on the process of angiogenesis, which is characteristic of and essential to nearly all malignant tumours [11, 12]. DCE MR attempts to differentiate between benign, borderline and malignant masses by attributing them to one of the three TICs as obtained by DCE. This systematic review shows type I TICs to be fairly predictive of benign origin of the ovarian mass, whereas type III TICs are predictive of malignancy. However, the assessment of enhancement patterns remains qualitative and might therefore be subject to user bias, similar to the evaluation of masses based on morphological criteria [55]. The use of semi-quantitative parameters deducted from the TIC, for example the enhancement amplitude and time to peak, might offer a solution to this subjectivity. Unfortunately, no reliable cut-off values could be extracted due to much heterogeneity of the studies regarding the semi-quantitative parameters analysed and their corresponding cut-off values as well as diagnostic performance. TIC type alone might not be sufficient in distinguishing between benign and malignant masses, since malignant lesions such as adenocarcinomas are sometimes found to be hypovascular, whereas benign masses, e.g. thecomas or sclerosing stromal tumours, might show hypervascularity [11]. Nevertheless, the diagnostic performance of the semi-quantitative parameters seems promising and DCE-MR imaging might thus form a valuable addition. We therefore support the advice of the ESUR to consider DCE-MR imaging in inhomogeneous solid masses on T2 or in complex cystic or cystic/solid masses with concern for malignancy. To deal with the aforementioned user bias and increasing extent of the diagnostic workup of ovarian masses (by incorporating DWI and DCE as well), there might be an interesting role for radiomics to play. This ‘data-driven’ approach which enables the extraction of innumerable quantitative features from tomographic images has already shown promising results in the classification of ovarian epithelial cancer, as well as in predicting several outcome measures [56, 57]. MR spectroscopy has also been reported to play a role in differentiating between borderline and malignant epithelial ovarian tumours [58]. However, epithelial tumours are rare in the paediatric population.

This systematic review faced some limitations. Data on the performance of MR imaging, combined with DWI and DCE, were largely deducted from studies performed in adult women (with no inclusion of paediatric patients), as MR imaging descriptions by paediatric studies were insufficient and no data from a purely paediatric cohort could be obtained. However, in order to minimise the risk of missing relevant studies, such studies and case reports in paediatric patients were included. The included studies showed much heterogeneity in MR imaging protocols, which made a meta-analysis impossible.

The description of the MR imaging features of the ovarian masses was very limited in the paediatric studies, which hampers the implementation for clinical use. Previously published reviews on the imaging of ovarian masses in children and adolescents were mainly based on findings in adult women [59–62]. This systematic review attempted to select studies applicable to children and adolescents, by exclusively including studies that were conducted either on paediatric patients or on adult women where at least 20% of the included patients had a malignant ovarian tumour other than carcinoma.

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that DWI, with ADC values measured in enhancing components, and semi-quantitative DCE might further increase the diagnostic performance of MR imaging in the pre-operative differentiation between benign and malignant ovarian masses. Furthermore, our data show that an ADC cut-off of 1.1 × 10−3 mm2/s might contribute to this differentiation. Prospective age-specific studies are needed to confirm the high diagnostic performance of MR imaging in combination with DWI and DCE techniques in children and adolescents with a sonographically indeterminate ovarian mass.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 119 kb)

List of abbreviations

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- AUC

Area under the curve

- DCE

Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- ESUR

European Society of Urogenital Radiology

- IOTA

International Ovarian Tumor Analysis

- MR

Magnetic resonance

- MRE%

Maximum relative enhancement percentage

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- ROI

Regions of interest

- SI60

Signal intensity at 60 s after enhancement

- SImax

Maximum absolute enhancement

- SIrel

Maximum relative enhancement

- THR

Time of half rising

- TICs

Time-intensity curves

- TTP200

Time to peak within 200 s after enhancement

Funding information

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Dr. A.M.C. Mavinkurve-Groothuis.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was not required for this study because this is a systematic review.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was not required because this is a systematic review.

Study subjects or cohorts overlap

Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in various articles (systematic review).

Methodology

• Systematic review

• Performed at one institution

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK Ovarian cancer incidence by age. In: Cancer Res UK https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/ovarian-cancer/incidence#heading-One. Accessed 1 Jan 2019

- 2.Kirkham YA, Lacy JA, Kives S, Allen L. Characteristics and management of adnexal masses in a Canadian pediatric and adolescent population. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(9):935–943. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)35019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanković ZB, Sedlecky K, Savić D, Lukač BJ, Mažibrada I, Perovic S. Ovarian preservation from tumors and torsions in girls: prospective diagnostic study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(3):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermans AJ, Kluivers KB, Janssen LM, et al. Adnexal masses in children, adolescents and women of reproductive age in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(1):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermans AJ, Kluivers KB, Siebers AG, et al. The value of fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis in ovarian masses in children and adolescents. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(6):1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavasolli F, Devilee P, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours (2003) Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. WHO Classification of Tumours, 3rd Edition, Volume 4

- 7.Forstner R, Thomassin-Naggara I, Cunha TM, et al. ESUR recommendations for MR imaging of the sonographically indeterminate adnexal mass: an update. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(6):2248–2257. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4600-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papic JC, Finnell SME, Slaven JE, Billmire DF, Rescorla FJ, Leys CM. Predictors of ovarian malignancy in children: overcoming clinical barriers of ovarian preservation. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(1):144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmerman D, Testa AC, Bourne T, et al. Simple ultrasound-based rules for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31(6):681–690. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomassin-Naggara I, Daraï E, Cuenod CA, et al. Contribution of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for predicting benignity of complex adnexal masses. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(6):1544–1552. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li HM, Qiang JW, Ma FH, Zhao SH (2017) The value of dynamic contrast–enhanced MRI in characterizing complex ovarian tumors. J Ovarian Res 10(1):4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Li X, Hu JL, Zhu LM, et al. The clinical value of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in differential diagnosis of malignant and benign ovarian lesions. Tumor Biol. 2015;36(7):5515–5522. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masch WR, Daye D, Lee SI. MR imaging for incidental adnexal mass characterization. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2017;25(3):521–543. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foti PV, Attinà G, Spadola S, et al. MR imaging of ovarian masses: classification and differential diagnosis. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(1):21–41. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0455-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vargas HA, Barrett T, Sala E. MRI of ovarian masses. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37(2):265–281. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohaghegh P, Rockall AG. Imaging strategy for early ovarian cancer: characterization of adnexal masses with conventional and advanced imaging techniques. Radiographics. 2012;32(6):1751–1773. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin Chem. 2015;61(12):1446–1452. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.246280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, et al. The Oxford levels of evidence 2. Oxford Cent Evidence-Based Med. 2011;1:5653. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao SH, Li HM, Qiang JW, Wang DB,, Fan H (2018) The value of MRI for differentiating benign from malignant sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: emphasis on diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J Ovarian Res 11(1):73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhang H, Zhang GF, He ZY, Li ZY, Zhu M, Zhang GX. Evaluation of primary adnexal masses by 3T MRI: categorization with conventional MR imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging. J Ovarian Res. 2012;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernardin L, Dilks P, Liyanage S, Miquel ME, Sahdev A, Rockall A. Effectiveness of semi-quantitative multiphase dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI as a predictor of malignancy in complex adnexal masses: radiological and pathological correlation. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(4):880–890. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2331-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasr E, Hamed I, Abbas I, Khalifa NM. Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in correlation with diffusion weighted (DWI) MR for characterization of ovarian masses. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2014;45(3):975–985. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Nishitani H. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of ovarian tumors: differentiation of benign and malignant solid components of ovarian masses. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34(2):173–176. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181c2f0a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansour S, Wessam R, Raafat M. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of ovarian masses with suspicious features: strengths and challenges. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2015;46(4):1279–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang P, Cui Y, Li W, Ren G, Chu C, Wu X. Diagnostic accuracy of diffusion-weighted imaging with conventional MR imaging for differentiating complex solid and cystic ovarian tumors at 1.5T. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:237. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsili AC, Tsampoulas C, Argyropoulou M, et al. Comparative evaluation of multidetector CT and MR imaging in the differentiation of adnexal masses. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(5):1049–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0842-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dilks P, Narayanan P, Reznek R, Sahdev A, Rockall A. Can quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI independently characterize an ovarian mass? Eur Radiol. 2010;20(9):2176–2183. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuboyama T, Tatsumi M, Onishi H, et al. Assessment of combination of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/computed tomography for evaluation of ovarian masses. Invest Radiol. 2014;49(8):524–531. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elzayat WA, El-Kalioubie M, Abdel-Naby MM, Abdel-Malek RR. The role of dynamic contrast enhanced MR imaging in the assessment of inconclusive ovarian masses. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2017;48(4):1159–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emad-Eldin S, Grace MN, Wahba MH, Abdella RM. The diagnostic potential of diffusion weighted and dynamic contrast enhanced MR imaging in the characterization of complex ovarian lesions. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2018;49(3):884–891. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansour SM, Saraya S, El-Faissal Y. Semi-quantitative contrast-enhanced MR analysis of indeterminate ovarian tumours: when to say malignancy? Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1053):20150099. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Feng F, Qiang J, et al. Quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging for differentiating benign, borderline, and malignant ovarian tumors. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018;43(11):3132–3141. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, Zhang GF, He ZY, Li ZY, Zhang GX. Prospective evaluation of 3T MRI findings for primary adnexal lesions and comparison with the final histological diagnosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(2):357–364. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2990-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao SH, Qiang JW, Zhang GF, Wang SJ, Qiu HY, Wang L. MRI in differentiating ovarian borderline from benign mucinous cystadenoma: pathological correlation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;39(1):162–166. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emil S, Youssef F, Arbash G, et al. The utility ofmagnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and management of pediatric benign ovarian lesions. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:2013–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marro A, Allen LM, Kives SL, Moineddin R, Chavhan GB (2016) Simulated impact of pelvic MRI in treatment planning for pediatric adnexal masses. Pediatr Radiol 46(9):1249–1257 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Thomas RL, Carr BR, Ziadie MS, Wilson EE. Bilateral mucinous cystadenomas and massive edema of the ovaries in a virilized adolescent girl. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(2 Pt 2):473–476. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182572654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willems RP, Slangen B, Busari JO (2012) Abdominal swelling in two teenage girls: two case reports of massive ovarian tumours in puberty. BMJ Case Rep. 10.1136/bcr.11.2011.5143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Park SM, Kim YN, Woo YJ, et al. A sclerosing stromal tumor of the ovary with masculinization in a premenarchal girl. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54(5):224–227. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.5.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghanbari Z. Premature thelarche and precocious puberty in a three-year-old girl with granulosa cell tumor. Int J Women’s Health Reproduction Sci. 2013;1(2):7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuboyama T, Hori Y, Hori M, et al. Imaging findings of ovarian dysgerminoma with emphasis on multiplicity and vascular architecture: pathogenic implications. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018;43(7):1515–1523. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bedir R, Mürtezaoğlu AR, Calapoğlu AS, Şehitoğlu İ, Yurdakul C. Advanced stage ovarian juvenile granuloza cell tumor causing acute abdomen: a case report. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(9):645–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boraschi P, Donati F, Battaglia V. Acute abdomen due to twisted ovarian immature teratoma in a 7-year-old girl. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(8):557–560. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318180ff05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaurasia J, Afroz N, Maheshwari V, Naim M (2014) Sclerosing stromal tumour of the ovary presenting as precocious puberty: a rare neoplasm. BMJ Case Rep bcr2013201124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Lin X, Wu D, Zheng N, Xia Q, Han Y. Gonadal germ cell tumors in children: a retrospective review of a 10-year single-center experience. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(26):e7386. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollmann N, van der Steeg HJJ, Semmekrot BA. A girl looking pregnant. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2017;161:D967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braun R, Peter A, Warmann S, Fuchs J, Binder G. Fast intraoperative testosterone assay confirms the location of an ovarian virilizing tumor in a young girl. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79(2):110–113. doi: 10.1159/000339683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calcaterra V, Nakib G, Pelizzo G, et al. Central precocious puberty and granulosa cell ovarian tumor in an 8-year old female. Pediatr Rep. 2013;5(3):e13. doi: 10.4081/pr.2013.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogers EM, Casadiego Cubides G, Lacy J, Gerstle JT, Kives S, Allen L. Preoperative risk stratification of adnexal masses: can we predict the optimal surgical management? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(3):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nejkovic L, Pazin V, Dragojevic-Dikic S. Carney complex and teratoma maturum ovarii--a case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33(6):672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hricak H, Chen M, Coakley FV, et al. Complex adnexal masses: detection and characterization with MR imaging—multivariate analysis. Radiology. 2000;214(1):39–46. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valentini AL, Gui B, Miccò M, et al. Benign and suspicious ovarian masses-MR imaging criteria for characterization: pictorial review. J Oncol. 2012;2012:481806. doi: 10.1155/2012/481806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jun SE, Lee JM, Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung IJ, Hahn ST. CT and MR imaging of ovarian tumors with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2002;22:1305–1325. doi: 10.1148/rg.226025033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kazerooni AF, Malek M, Haghighatkhah H, et al. Semiquantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for accurate classification of complex adnexal masses. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45(2):418–427. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang H, Mao Y, Chen X et al (2019) Magnetic resonance imaging radiomics in categorizing ovarian masses and predicting clinical outcome: a preliminary study. Eur Radiol:3358–3371 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Rizzo S, Botta F, Raimondi S, et al. Radiomics of high-grade serous ovarian cancer: association between quantitative CT features, residual tumour and disease progression within 12 months. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(11):4849–4859. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma FH, Li YA, Liu J, Li HM, Zhang GF, Qiang JW (2018) Role of proton MR spectroscopy in the differentiation of borderline from malignant epithelial ovarian tumors: a preliminary study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 10.1002/jmri.26541 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Pai DR, Ladino-Torres MF. Magnetic resonance imaging of pediatric pelvic masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2013;21(4):751–772. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heo SH, Kim WJ, Shin SS et al (2014) Review of ovarian tumors in children and adolescents: radiologic-pathologic correlation 1. Radiographics 34(5):2039–2055 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Lam CZ, Chavhan GB (2018) Magnetic resonance imaging of pediatric adnexal masses and mimics. Pediatr Radiol 48(9):1291–1306 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Epelman M, Chikwava KR, Chauvin N, Servaes S. Imaging of pediatric ovarian neoplasms. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41(9):1085–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 119 kb)