Abstract

Expectations relating to treatment and survival, and factors influencing treatment decisions are not well understood in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. This study analyzed combined findings from a targeted literature review with patient-reported information shared on YouTube to further understand patient perspectives in hematologic cancers and, in particular, acute myeloid leukemia. The targeted literature review included articles concerning patient (aged ≥ 18 years) experiences or perspectives in acute myeloid leukemia or other hematologic cancers. YouTube video selection criteria included patients (aged ≥ 60 years) with self-reported acute myeloid leukemia. In total, 26 articles (13 acute myeloid leukemia–specific and 14 other hematologic cancers, with one relevant to both populations) and 28 videos pertaining to ten unique patients/caregivers were identified. Key concepts reported by patients included the perceived value of survival for achieving personal and/or life milestones, the emotional/psychological distress of their diagnosis, and the uncertainties about life expectancy/prognosis. Effective therapies that could potentially delay progression and extend life were of great importance to patients; however, these were considered in terms of quality-of-life impact and disruption to daily life. Many patients expressed concerns regarding the lack of treatment options, the possibility of side effects, and how their diagnosis and treatment would affect relationships, daily lives, and ability to complete certain tasks. Both data sources yielded valuable and rich information on the patient experience and perceptions of hematologic cancers, in particular for acute myeloid leukemia, and its treatments. Further understanding of these insights could aid discussions between clinicians, patients, and their caregivers regarding treatment decisions, highlight outcomes of importance to patients in clinical studies, and ultimately, inform patient-focused drug development and evaluation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40271-019-00384-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| Both the targeted literature review and YouTube video searches provided complementary and valuable information on the patient experience and perceptions of hematologic cancers, in particular for acute myeloid leukemia. |

| Key concepts reported by patients included the perceived value of survival, the emotional/psychological distress of their diagnosis, the availability and impact of treatment options, and uncertainties about life expectancy/prognosis. |

| The patient experience is complex and multifactorial, thus patient management and treatment decisions in clinical practice should be made jointly between patients and clinicians, and need to reflect the expectations, goals, and preferences for a given individual. |

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is one of the most prevalent types of blood malignancies, although overall it is a rare orphan malignancy [1–3]. The incidence of AML increases with age, with the mean age at diagnosis between 65 and 70 years [1–3]. Remission rates in older patients (aged ≥ 60 years) are lower and relapse rates are higher, typically resulting in death within weeks or months of diagnosis [4, 5]. The median survival of patients with AML ranged from 6.2 to 11.0 months, and survival decreased with increased age [6–11]. In a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis from 1997 to 2006, 5-year relative survival rates decreased with increasing age in male and female patients, respectively: 21.1% and 24.3% of all ages, 6.8% and 9.3% aged 65–74 years, 1.5% and 1.1% aged 75–84 years, and 1.2% and 0% aged ≥ 85 years [12].

For older patients with AML, there is no standardized treatment pathway; there is a reluctance to treat the older patient population with intensive chemotherapy, with clinicians favoring less intensive chemotherapy or best supportive care [2]. In a population-based study in the USA, only 38.6% of 5480 patients with AML received chemotherapy within 3 months of diagnosis [13]. Older patients have a higher incidence of comorbidities and adverse molecular and cytogenetic abnormalities, and are at a higher risk for treatment-related morbidity and mortality, all of which contribute to a generally poorer prognosis [2, 3, 14]. As well as impacting treatment decisions, these clinical factors may negatively affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [15].

The assessment of HRQoL has become increasingly important in oncology; however, HRQoL in hematology, and specifically AML, has received relatively little attention [16–19]. Furthermore, there is little published information on the perspectives of older patients with AML in terms of their expectations for treatment and survival, and which non-clinical factors influence their treatment decision-making process. More recently, there has been a rise in patient involvement and engagement in clinical research, and patient-centered information is becoming increasingly important in healthcare decision making [20, 21]. Patient-reported information and patient-reported outcomes are forms of patient-centered information. A patient-reported outcome measure assesses one or more aspects of a patient’s health status (e.g., HRQoL, symptoms, treatment satisfaction) based on information gathered directly from the patient, without interpretation by clinicians or others, and can be utilized in clinical trials and clinical practice [21]. Patient-reported information is experiences reported by patients and caregivers regarding the disease and treatments outside the constraints of formal research, including clinical trials, and in an unsolicited manner [21].

Draft guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration advocates the value of social media as a complementary data-collection method during the preliminary stages of a research study, or as a supplement to traditional research methods such as literature reviews and surveys [22]. In particular, the US Food and Drug Administration guidance highlights social media searches as a method to gain insight on the patient perspective of symptoms and disease impact [22]. Compared with traditional methods, social media data can provide a large-scale, rapid, and cost-effective means to capture patient-reported information in an easily accessible manner [21, 23–25]. Although social media data are generally self-reported, have no interviewer bias, and have fewer resource burdens vs. traditional sources, data can be inconsistent and limited. Furthermore, there remains some uncertainty in the representativeness of the information being reported on social media [21, 23–25]. Varying results have been reported in other therapy areas where YouTube was utilized for communicating health and medical treatment information [26–30].

To further understand patient perspectives with regard to treatment decision making and the value of extended life vs. quality of life (QoL), data were obtained from a targeted literature review as well as publicly available patient-reported information shared on YouTube. A particular focus of these analyses was to gain insights from patients with AML on their disease experience and treatment perceptions; however, this was expanded to include other hematologic cancers, owing to the paucity of research in this condition. Additionally, the study aimed to preliminarily assess the feasibility of using YouTube as a supplementary method for collecting patient-reported information in patients with hematologic cancers, in particular, patients with AML.

Methods

Targeted Literature Review

Searches of computerized bibliographic databases—PubMed (MEDLINE), EMBASE, and PsycINFO—were conducted to identify relevant publications using the OVID platform and a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. A focused search strategy applied a combination of population-specific, broad HRQoL/QoL, qualitative research and value of extended life terms (see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). The primary focus of this preliminary search was to explore existing research in patients with AML. Following the initial searches in OVID, an additional search was conducted to include other hematologic cancers, e.g., chronic myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma (see ESM). Supplementary searches were also performed in Google Scholar. Published guidance and conference proceedings from major hematology and oncology congresses (American Society of Hematology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, Bloodwise, European Hematology Association, and European Society for Medical Oncology) were also reviewed.

The titles and abstracts of the articles generated by searches were reviewed to identify relevant publications (journal articles vs. conference abstracts and excerpts). To be eligible for inclusion, articles were required to have a relevant clinical term included in the title and/or abstract (e.g., ‘AML’ or ‘Acute Myeloid Leukemia’), the main focus of the article on patient experience or perspectives, and the study population ≥ 18 years old. Articles were published within the past 15 years (range 2003–2018). Abstracts not related to the value of extended life in patients with hematologic cancers or their caregivers, or that were unavailable in English, were excluded.

The following information was extracted from each article: author, title, publication type, study objectives, study population, and study design. The value of living longer was explored from the patient and caregiver perspectives, for example, by using descriptions of target or expected life milestones. Qualitative descriptions from the patient, caregiver, and healthcare professional perspective around treatment decisions were also extracted. Finally, and where possible, other relevant factors related to treatment decision making, i.e., evidence of transfusion independence, frequency of clinic or hospital visits, location of treatment center, and incidence of infections, were obtained from each article.

YouTube Analysis

YouTube was selected as it is a global online platform where registered users can easily upload and share videos. Videos that are uploaded with “public” privacy settings can be viewed by any Internet user. According to the YouTube Press statistics, YouTube has over a billion users; nearly a third of all internet users. Furthermore, YouTube has previously been used for conveying health information in a number of therapy areas [26–31]. Finally, YouTube was selected because it is a widely used and well-known platform, familiar to a broad range of age groups. This was in line with the study objectives on investigating the feasibility of a general social media platform for accessing patient-reported information.

Video data were collected via YouTube. Searches focused on identifying videos uploaded by patients with AML or their family members within the past 3 years. For ease of reporting, family members are referred to as ‘caregivers’ for the YouTube analyses. An initial search (Stage 1) focused on patients aged ≥ 60 years or older who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy. This criterion was expanded in the secondary search (Stage 2) to include patients aged ≥ 60 years who were receiving intensive chemotherapy. This decision was made to increase the number of available videos for review and to further inform on the decision-making process for accepting or rejecting chemotherapy. To identify potentially relevant videos, searches were conducted in an iterative manner using key search terms singularly and in combination, as appropriate (see ESM).

Video screening was conducted in three steps: screening for relevance (Step 1), screening for patient characteristics (Step 2), and video review (Step 3). Step 1 involved manual screening to remove irrelevant videos, e.g., clinician presentations or marketing videos. In Step 2, further manual screening was performed to identify videos that met key patient characteristics. Patients were ≥ 60 years of age, either self-reported or researcher determined. Step 2 consisted of a staggered approach with an initial search (Stage 1) to identify patients who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy treatment and a secondary search (Stage 2) to include patients receiving intensive chemotherapy. Stage 1 criteria for patients ineligible for intensive chemotherapy were level of unfitness (either self-reported or patient report of clinical evaluation that would exclude them from intensive chemotherapy) or patient-reported use of any of the following treatments: low-dose cytarabine (Cytosar-U®), azacitidine (Vidaza®), decitabine (Dacogen®), palliative care, end-of-life care, allopathic medicine, or non-intensive treatment. The Stage 2 criterion was patient-reported use (current or previous) of intensive chemotherapy treatment. In Step 3, video footage was reviewed to identify the relevance of the content to address the study research questions. Selected videos were retained for in-depth review and analysis.

Because social media patient-reported information exists outside the research context, key patient demographic and diagnostic characteristics were not always available and age was not consistently reported on YouTube videos. If age was not reported, researchers judged approximate age. Content was analyzed thematically to address the key research questions on treatment decisions and preferences.

Ethics and Reporting of Results

Prior to data collection, one of RTI International’s institutional review boards reviewed the YouTube study and determined the social media review did not constitute clinical research with human subjects. Ethics approval was deemed unnecessary as the study data were located within the public domain. Ethics approval was not required for a literature review study.

For the purposes of reporting the results, the key themes emerging from both the targeted literature review and YouTube search were combined. Additionally, as the same search criteria were used, the findings from patients with AML and those with other hematologic cancers were combined.

Results

Literature Review

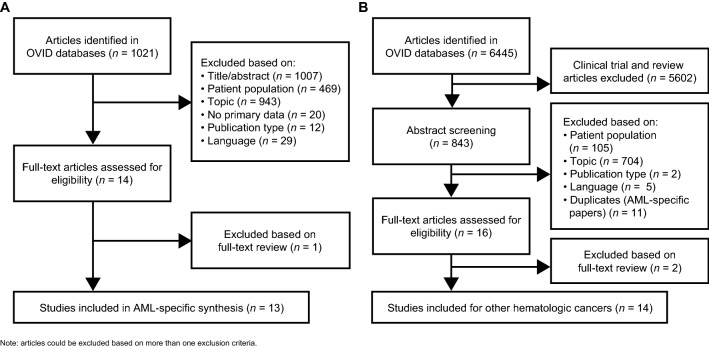

In the targeted literature review, 1021 abstracts were identified from the search of AML-specific articles (Fig. 1). No additional papers were identified through supplementary searches, e.g., Google Scholar and conference proceedings. Fourteen abstracts were selected for full-text review, comprising 11 journal articles and three conference abstracts. All articles were published within the past 15 years (range 2003–2018). One article focused on older patients with AML who were not receiving intensive chemotherapy and the remaining articles focused on patients with AML who were eligible for chemotherapy. One article was excluded because the findings were focused on the presentation of symptoms experienced by patients with AML.

Fig. 1.

Literature search results. a Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and b other hematologic cancers

In the expanded supplementary search of other hematologic cancers, 6445 abstracts were identified (Fig. 1). Searches were conducted only within the OVID platform and review articles and those focused on clinical trials were excluded. Sixteen abstracts were selected for full-text review; all were journal articles that had been published between 1986 and 2018. Of these 16, two papers were later excluded as the findings did not meet the objectives of the literature review. The papers covered a range of hematologic cancers, including lymphoma (n = 11), myeloma (n = 7), and leukemia (n = 6). Some papers included patients with non-hematologic cancers (n = 3); however, all papers contained at least one participant in the study population who had a hematologic cancer.

A total of 26 articles were selected for inclusion in the targeted literature review synthesis: 13 AML-specific and 14 other hematologic cancers, with one article with findings relevant to both populations [32–57]. Most articles selected for inclusion were qualitative research studies (n = 23), providing rich detail regarding the patient perspective.

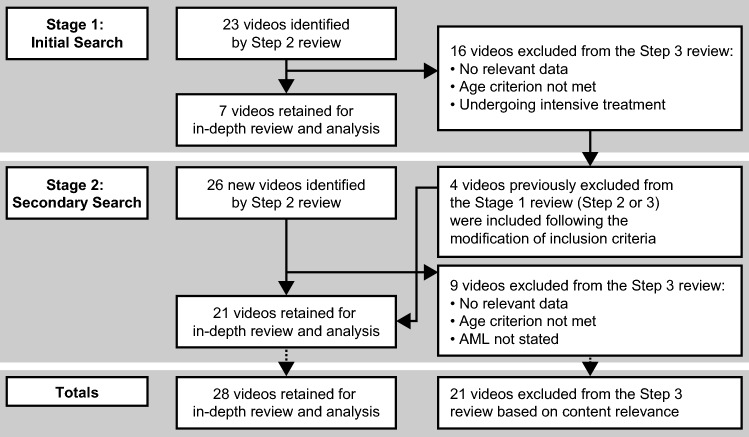

YouTube Search

In the YouTube search, 49 videos were identified and comprised a total of 3 h, 52 min of video footage (Fig. 2). Twenty-one videos (60 min of video footage) were excluded and the analysis included 28 videos (2 h, 52 min of video footage) relating to ten unique patients with AML. Of the ten patients or caregivers, eight were patients with AML reporting on their personal AML experience. One was a patient who uploaded a video along with his wife (both of whom provided information on the patient’s AML experience) and one was a deceased patient whose wife had uploaded a video reporting on her late husband’s experience. Six of the patients were male and ages ranged from 60 to 80 years. The majority of videos (n = 21; 75.0%) had been uploaded to YouTube within the past 3 years. The mean video duration was 6 min, 9 s (range 2 min, 28 s to 14 min, 1 s). Eighteen (64.3%) videos had been self-published on YouTube by the patient; the remaining ten videos had been posted by medical centers/organizations (n = 5; 17.9%), commercial/pharmaceutical companies (n = 3; 10.7%), and charities/patient advocacy groups (n = 2; 7.1%). The videos posted by commercial/pharmaceutical companies included a disclaimer stating that the patient testimonial was homemade by the patient and the unedited video had been posted on their behalf.

Fig. 2.

Staggered approach for searching YouTube. AML acute myeloid leukemia

The key themes emerging from both data sources, and in patients with AML and other hematologic cancers, were combined to inform on the disease experience and associated treatments from the patient perspective.

Patient Experience Following Diagnosis

Several aspects of the patient experience following diagnosis were raised and discussed (Table 1). A key area of impact on both patients and caregivers was the emotional/psychological distress of their AML or hematologic cancer diagnosis. In both YouTube videos and literature review articles, patients and caregivers highlighted that they felt uncertain about life expectancy and prognosis, and that death was imminent soon after diagnosis. As a consequence of these uncertainties, there was a strong sense among patients and caregivers that it was not worth planning too far in advance [32–36, 43, 46, 55].

Table 1.

Patient quotes on experience following diagnosis

| Key findings | YouTube (all patients with AML) | Literature review |

|---|---|---|

|

Uncertainty surrounding life expectancy and prognosis Feeling of impending death and inability to plan in advance |

“it was just a very scary time, the frightening part of the whole situation is that they [doctors] haven’t got a clue as to what causes this [AML] or what they can do to effectively isolate it, contain it, stabilize it.” “… has a lot of things going through my head about, you know, how I got this, why I got this.” “… find it impossible to believe I’m going through this, I don’t [know] if, when the denial ends erm, maybe never ‘cause I think anger is the next stage.” |

“It was like, well, chances of survival stopped meaning anything for me once I got diagnosed. Thirty percent, 50% percent, 100, it didn’t matter.” (patient with AML) [32] “I feel like there’s an expiration date hanging over me, which I wasn’t aware of before.” (patient with AML) [33] “… there’s a lot of uncertainty and it’s not just like getting through a week and then everything is okay, that uncertainty is going to be there for months, if not years.” (patient with AML) [33] “The bit that’s getting us down is, how long have we got with her? … The big uncertainty, that’s worse than the big ‘C’, the big ‘U’.” (patient with CTCL) [34] “‘Hospice.’ I don’t like that word. I don’t like that word … leave me alone, I’m alive, I’m getting on with it. Now they don’t even use that life expectancy, they don’t use that word now which is good.” (patient with MM) [35] “It went from a state of shock, then I thought, as they say, ‘put your business in order’ because you know, I don’t know, I didn’t know whether I was going to be around the next year or what.” (patient with MM) [36] “I decided I like reading the New Yorker—the magazine. So I said ‘You know I think I will get a subscription.’ And when I called to get a subscription, they said to me ‘Do you want one or two years?’ And I thought, ‘How can I get a subscription for two years? I probably won’t even be here in two years.” (patient with MM) [36] |

| Willingness to continue | “I feel guilty cause I’d lie in bed all day, yeah. I feel like I should be up and about, you know, they say you’re supposed to fight these things and I don’t have it in me.” |

“The bike’s ready to go but I’m not.” (patient with AML) [37] “I go out as much as I can … I think if you stay active it kind of puts it out of your head a little bit and I think you get a better chance at a cure by living a normal life as close as you can … That’s probably even more important than staying alive because if I can’t look after myself, I don’t want to be here.” (patient with AML) [37] |

|

Patients’ worries and frustrations The impact on personal relationships, both current and future |

“What I worry about is how I’m going to, at my age, how am I going to meet someone and build a future with someone. I mean you can’t really promise the person that you may [be] there for a very long period of time. I don’t think it’s really fair to meet someone and be burdening them with your difficulties. So that’s the quandary I’m facing.” (patient with AML) [38] “The question I was avoiding, the thing that hurt me the most, was losing my hair … That seemed worse than dying to me, being twenty-two.” (patient with AML) [39] “I just really wanted to last long enough to tidy up all the loose ends I guess at the time, all the things that hadn’t been said, a lot of things I wanted to write down, tidying up all the loose ends before I actually died.” (patient with NHL) [39] “It’s just sometimes I feel a bit jealous you know, I have friends retiring now from being lecturers, this kind of thing, and buying a house in Turkey, or buying a house in France and planning the next 20 years. And they’ve talked to me about it and asked me what I’m going to do, and I say, ‘I’m not too sure’.” (patient with MM or ALL) [40] “My partner and I split up because I don’t think he could handle it at all.” (patient with MM or ALL) [40] |

|

| Reprioritizing who and what was important |

“In terms of going back to my career now, I totally plan to do that, but I’m not so sure I want those same driven type goals anymore. I’m not sure that those are necessarily what I want to do. I look at life in terms of time, and I just sometimes think that those pursuits, those goals have cost me time with my family, my kids, friends, other things, and I start to question now is that what I really want to do? Do I want to be that career driven? And I’m not so sure I do anymore. I don’t think I care so much about that.” (patient with AML) [38] “[My brother and I] didn’t talk for several years. What happened was all these pills are not working. Nothing’s working. I just went upstairs, lay across the bed. I said, ‘I’m done. I’m not taking any more medication. I’m done. Whatever happens, happens. I’m done, finished. …’ Boy, that was a mess. … Then my brother showed up into the picture. That relationship completely flipped. … I never had a relationship with him ever like it is now. … Absolutely close. A crowbar’s not going to work [to separate us].” (patient with NHL, prostate or breast cancer) [41] |

|

|

Acceptance of the diagnosis Maintaining a positive attitude and a sense of normality |

“… the leukemia chapter is kind of pleasant. I can sit and just think about things.” “I officially have permission to ask other people to wait on me.” “You have to have patience, stay strong, and don’t give up.” “I remember when I was trying to do my treatment, I brought my work with me and I just pretended I’m in a normal situation, just keep myself going as a normal person although I know I’m sick.” |

“(Crying) And they [my children] are grown, and I know they’re on their way, that they can get along without me. The saddest part, I think, is that I won’t ever see them again, and that makes me sad.” (patient with lymphoma, colon or lung cancer) [42] “You know, when I walk in [my home] I feel like I’ve got to be strong for everybody else who’s there, so I switch off from my morbid ways, and I turn into this big smiling person and I don’t stop smiling until I’ve left them, so they never see this.” (patient with MM) [43] |

|

Patients and caregivers expressed gratitude for having remaining time There was a stronger appreciation for living in the present |

“You do learn to live for the day and live for the moment and you learn to appreciate the things that are going on now rather than always thinking about either backwards or forwards. And he says a lot, he talks about the phrase, ‘counting your blessings,’ you know, you do begin to appreciate things, the little things you do have, as much as, you know, because when things are taken away from you, you realize that things can go [laughs].” (patient with CTCL) [34] “My greatest joys are that I have lived another day, that I still have Ed [my husband], the children, my sister, my mother, and lots of good friends and neighbors.” (patient with lymphoma, colon or lung cancer) [42] “I appreciate any time we have together way more than I would have done I think, um, because every moment’s precious and my, my eldest son feels the same; he, you know, when he’s not working he’ll come and see, um, my mum and spend time with, well my mum and my dad, you know. So yeah, it does make you think, yeah, that time’s precious, definitely.” (patient with CTCL) [34] “I think it just sort of makes you appreciate living more. I mean obviously I have days where I lose that perspective, but yeah, it makes you appreciate the small things in life, just like … the uncertainty of life for everybody, really. I mean, you never really know what’s going to happen. You’re not invincible. You’re not here forever.” (patient with lymphoma, breast or kidney cancer) [44] |

For some of the papers, participants who had non-hematologic cancers (n = 3) were also included; however, all papers reviewed contained at least one participant with a hematologic cancer in the study population

ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, APL acute promyelocytic leukemia, CML chronic myeloid leukemia, CTCL cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, MDS myelodysplastic syndromes, MM multiple myeloma, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Another common theme was the worries and frustrations experienced by patients following their diagnosis. These ranged from dealing with the side effects of treatment to the impact of their diagnosis on personal relationships. From literature review sources, some patients reported strains on their existing relationships or expressed worries that their diagnosis would prevent the possibility of future relationships [38–40]. In tandem with these concerns was a prevailing need to complete specific tasks before they died, but also a reprioritizing on who or what was important to them, e.g., their career or making amends with family members [38, 41].

As expected, the patient experience is complex, particularly in patients with AML. In both data sources, patients with AML described how they experience a lack of energy or willingness to fight their condition, and this was associated with feelings of guilt [37]. However, many patients also detailed their acceptance of their AML diagnosis and how they strive to have a positive disease outlook and retain a sense of normality in their everyday lives. Across patients with hematologic cancer, there was a stronger appreciation for living in the present, and both patients and caregivers expressed gratitude for having remaining time with their loved ones [34, 42–44].

Achievement of Life Milestones

Generally, and from both YouTube videos and literature review sources, patients and caregivers focused on the perceived benefits associated with living longer, and in particular, reaching life milestones (Table 2). Life milestones included reaching the next birthday and a desire to be alive for family occasions, e.g., weddings or births. Younger caregivers found it especially hard to accept the prognosis of AML or other hematologic cancers. They felt there were many important milestones that their spouse or parent would miss out on. Additionally, parents of younger children seemed more anxious about leaving their children, especially those children who had major life events ahead of them [36, 39, 40, 44, 55].

Table 2.

Patient quotes on life milestones

| Key findings | YouTube (all patients with AML) | Literature review |

|---|---|---|

| Personal milestones (e.g., reaching their own next birthdays) or feeling too young to die | “I had another birthday… didn’t think I’d see that one, but I did, and I just can’t say how, how great it feels to be on the other side of my darkest days.” | “I have been able to sort of put it in context and deal with the most profound thing that has ever happened to someone. Which is one’s impending death. … I am not going to plan a birthday party 10 years from now. I probably won’t see my children through high school. It’s things like that that chokes me up …” (patient with MM) [36] |

| Ability to attend children or grandchildren’s milestones (e.g., weddings, graduations, concerts) or being able to watch them grow up |

“The only thing that went through my head was ‘I will not see my beautiful daughter walk down the aisle.’ There was no concern for me; that was one thing I wanted to fulfill.” (patient with NHL) [39] “I love my family and I know they love me as well, and I want to be with them for a little longer. I’d like to see my daughters get married and I’d like them to have a baby. I’d like them to have a family, you know, and to see the family before I pass away.” (patient with MM or ALL) [40] “I have been able to sort of put it in context and deal with the most profound thing that has ever happened to someone. Which is one’s impending death. … I am not going to plan a birthday party 10 years from now. I probably won’t see my children through high school. It’s things like that that chokes me up…” (patient with MM) [36] “The one thing that really gets me nuts is leaving the kids.” (patient with MM) [36] |

|

| Goals were often set by patients to cope with the uncertainty of the disease, and usually revolved around children |

“You have goals, or I do. I am a very methodical person. [I] have things planned, and maybe that is why this is hard, too, because I didn’t plan this … The first goal I had after I was sick—I was really ill—was that I would live ‘til the grandchild was born in December and that was from June ‘til December … And then my goal after that is, I don’t know… I guess live to Christmas again so that I can see my kids.” (patient with lymphoma, colon or lung cancer) [42] “This is one thing I want to do. If I’m going to die I’m going out having achieved this.” (patient with NHL) [39] |

|

| Younger caregivers found it especially hard to accept the prognosis, as they felt there were many events their spouse or parent would miss out on, especially important milestones | “… without the clinical trial, you know… my kids will grow up without a dad … I won’t have a husband.” |

“I think losing a parent is hard on anyone regardless of what age they are… but I think it’s easier to deal with it when you’re in your forties, because it’s expected. Like, your parents are old! They’re supposed to die when they’re old. But because we’re so young, there’s still so many things that haven’t happened in our life that our parents are supposed to be a part of.” (patient with lymphoma, breast or kidney cancer) [44] “They’re supposed to be grandparents to our children. They’re supposed to be there for our weddings. And they’re supposed to be here to meet the man that we fall in love with… and it’s so scary that they aren’t, that they might not be able to see those fabulous parts of our lives that they are supposed to see before they die.” (patient with lymphoma, breast or kidney cancer) [44] |

| Others were very grateful for the opportunity to see their family reach important milestones, such as having children | “I feel like a pretty lucky grandpa, you know, to be a little longer to see my grandkids grow up… have some kind of life, and I just hope I continue to do.” | “So much has happened in the years since I had cancer, so many wonderful things that I’ve been able to enjoy – family, grandchildren, great grandchild. So, those are things that I never would have been around to see. … I am happy.” (patient with NHL, prostate or breast cancer) [41] |

For some of the papers, participants who had non-hematologic cancers (n = 3) were also included; however, all papers reviewed contained at least one participant with a hematologic cancer in the study population

AML acute myeloid leukemia, MDS myelodysplastic syndromes, MM multiple myeloma, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma

As reported in some articles, patients would often set goals to cope with the uncertainty of the disease, and these goals usually revolved around children or grandchildren. Many patients expressed their gratitude at having more time with their family, being able to attend family events, and/or reaching a life milestone [39, 41, 42].

Treatment Decision Making

Decisions for treatments were often governed by clinical factors (Table 3). In both YouTube videos and the literature review, the patient age, comorbidities, and tolerability issues were all factors reported as having prohibited patients with AML from receiving intensive, potentially life-extending chemotherapy. For example, ineffectiveness of prior treatments and side effects such as hallucinations and loss of appetite were some of the reasons cited for not receiving intensive chemotherapy.

Table 3.

Patient quotes on treatment decision making

| Key findings | YouTube (all patients with AML) | Literature review |

|---|---|---|

|

Patients were uncertain about the treatment pathway and felt resentful that there was no ‘exact’ treatment for cancer There was a patient-perceived ineffectiveness of chemotherapy, and expectations regarding success of treatment differ from clinical estimations of survival time |

“[Blood counts] went down and just as they were beginning to rebound, they were hit again with the regimen and they went down again, so it seemed like, you know, trying to dig your way out of a, a sand trap.” |

“… not having a clear defined treatment that works. Unlike friends who have other types of cancer where it is you have surgery, you have radiation, you have this protocol that either works or doesn’t. It’s been very open-ended … I like control.” (patient with AML) [33] “Cancer is an extreme disease. Nothing is useful against it – so, there is no exact treatment. Cancer is the worst. There’s no treatment … it makes me resentful.” (patient with AML or ALL) [45] “You know, I have had so many different medications that didn’t work, I can’t get myself worked up for things anymore because it’s too disappointing, you know, when it doesn’t.” (patient with MM) [36] |

|

Weighing quality of life vs. the length of life Having more time was of high importance to patients, despite the unpleasantness of treatment |

“I don’t want to compromise my life.” “They did say I would lose my hair and I’m going to get sick, but if that’s the least of my worries, then I got this.” |

“You are 64, you have AML from MDS; all these things are against you. … It all depends on what you’re looking for in your treatment and what your goal is. If your goal is cure then a BMT is the only thing that is going to get you cured, but there’s only a 40–50% chance of cure and a 20–30% chance of dying from the transplant. … There’s a 20–50% chance of long-term survival. … You have to ask what is important to you.” (patient with AML) [46] “It’s not quantity but quality of life.” (patient with AML) [46] “She wanted anything, if it could prolong things, if it could give her more time, then she wanted to have it.” (patient with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma) [47] “I was willing to do everything this first time. I was 49 when this thing started and … I didn’t want to die. But I really don’t want to do this again. So I am not even sure what will happen when this thing returns.” (patient with MM) [36] “I wonder sometimes if I live 7 years, if I live 10 years, how much of that will I be involved in just coming for chemotherapy.” (patient with MM) [36] “… even when I was going through treatment I did not let it dominate my life.” (patient with NHL, prostate or breast cancer) [41] “It means that, as I said to my son when I was going through chemo, you know, ‘I’ve got too many things in my life to do.’” (patient with NHL, prostate or breast cancer) [41] |

|

Chemotherapy was described as a ‘harsher’ option compared with palliative care Concern over side effects and stress related to the highly invasive treatments and procedures |

“I don’t want this, I don’t like this feeling; I want it to stop.” “I’ve refused chemo because it’s not gonna really help me. It’s supposed to… extend my life but I have to be in the hospital for infusions 5 to 10 days a month for the rest of my life. I don’t feel like doing that. I’d rather stay home and have a good life.” “… they gave me a few options: another round of chemo, the same type that I had had which I physically was fairly sure I couldn’t handle, the other was a different type of chemo where you get chemo for 5 consecutive days then you’d have 23 days off … the other two options clinical trial … or the last one was hospice, and none of those options really at the time seemed palatable to me. The only one that had any inkling to me of the possibility, because I could do it locally, was the 1 hour a day for 5 days, 23 off and then you do it again. I went through that regimen twice.” “I did notice my hair starting to fall out, so I thought I was mentally prepared for that but I guess I’m not, but that’s okay, it’s another hurdle I’ll get over.” “Today was a bad day though, today is when everything hit me, my counts dropped drastically, I’m nauseous, very bad runs erm, extremely tired to the point where I don’t even want to get out of bed, but they make me, but again for everything that ails you, they’ve got something that you can take to fix it.” |

“… [you] either take the chemo or DIE! Period. Because otherwise the leukemia cells would just stick in my blood and cause me to have a brain aneurysm… or heart attack or whatever. There was really no choice. You either DID this or die.” (patient with AML) [54] “Well, he told me that … there were two options that I could’ve gone. One, the harsher … way to go, but I might be able to live longer. Or the one with better, um, palliative way of life, but I wouldn’t live as long. I’m not quite ready to die yet, so I thought, well, we’ll try the harsher way. And since my health is relatively good overall, I thought I’d probably be able to handle that.” (patient with AML) [54] “I know I couldn’t have done [undergone the difficult treatments] that he did (crying) to the point, that it really worries me now.” (patient with NHL, AML, CML, ALL or CLL) [49] “To see [the patient] strapped up like a rotisserie chicken, bound with sticky tape and being baked in there for 20 minutes for three days. And I used to watch through the window, crying my eyes out and the nurses would say he has music in there. I didn’t need that.” (patient with NHL, AML, CML, ALL or CLL) [49] “I personally think we treat far too many people far too aggressively, that the thrust of AML is completely wrong, if the patient is over 60 or 70 you are never going to cure them. Taking a more palliative, quality of life approach would probably be better.” (patient with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma) [47] |

| Some wanted treatment up until the very end of life |

“He was a fighting spirit … he wanted to go on being treated … he wanted treatment to the end.” (patient with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma) [47] “She wanted anything, if it could prolong things, if it could give her more time, then she wanted to have it.” (patient with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma) [47] |

|

| Hope that there were other possible treatments | “… because of the treatment, because of the funding and this clinical trial, we’re standing here in front and still alive after 10 years, and we’re really blessed and we’re really glad to know that those, those research really keep us here.” | “Well, my attitude is the further you put it off the better but I accept the fact like they [doctors], said to me, this time if I have this treatment it’s going to be a bit distressful, make me ill for a short period, but it could give me another 5 years.” (patient with MM or ALL) [40] |

For some of the papers, participants who had non-hematologic cancers (n = 3) were also included; however, all papers reviewed contained at least one participant with a hematologic cancer in the study population

ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, APL acute promyelocytic leukemia, CML chronic myeloid leukemia, CTCL cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, MDS myelodysplastic syndromes, MM multiple myeloma, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Patients in both data sources also discussed the lack of a clear defined treatment pathway and felt resentful that there was no ‘exact’ treatment for AML or hematologic cancer. Additionally, there was a patient-perceived ineffectiveness of chemotherapy, and expectations regarding the success of treatment differed from clinical estimations of survival time. For example, for some patients where prior therapies had failed, they did not want to be too hopeful that a promising treatment would be effective [33, 36, 45]. In parallel, some patients expressed their gratitude to scientific research for prolonging their lives and remained hopeful that there would be new and better treatments in the future for AML or other hematologic cancers.

For patients in both data sources who were eligible for chemotherapy, concern over side effects, tolerability issues, and stress related to the aggressive treatments and procedures were common reasons for their decision not to receive treatment. Another key feature of treatment choice was patients’ willingness to undergo or continue treatment; some patients reported they no longer had the energy or fortitude to undergo intensive treatments [32, 47–49, 52, 54]. Whereas, in one article, other patients wanted treatment right up until the very end of life [47]. Among patients with AML, many described feeling trapped between two undesirable treatment choices—intensive chemotherapy vs. palliative or best supportive care; choosing intensive chemotherapy to extend their life was accompanied with the acceptance of potentially distressing side effects associated with this treatment [36, 40, 41, 46–48, 54].

Health-related QoL was an important consideration for patients, in addition to the quantity or length of life [36, 41, 46, 47, 51, 53]. One AML-specific article reported that 97% of patients agreed with the statement that HRQoL was more important to them than the length of their life, regardless of their choice of therapy [51]. Patients with AML or other hematologic cancers emphasized the importance of maintaining a ‘normal life’ following their diagnosis and, in particular, the ability to engage in their hobbies and daily activities. However, effective therapies with the potential to extend life were of greater importance to patients/caregivers and for some patients, it outweighed potentially severe side effects [36, 40, 41, 47]. As a result, many patients eligible to receive intensive chemotherapy chose this option over low-intensity treatments.

Importance of Treatment Experience

Patients with AML or other hematologic cancer detailed a number of other aspects of their treatment as being important factors in their HRQoL and daily activities (Table 4). In both the YouTube videos and literature review sources, patients reported that extended time spent in the hospital and traveling for medical appointments had a detrimental impact on their finances and family life; patients often spent time away from their families and missed out on activities with friends or family. Additionally, patients and caregivers (in the literature review only) felt that they could not make plans because of appointments [32, 34, 36, 37, 40, 43, 48, 50, 52, 53, 56, 57].

Table 4.

Patient quotes on the value of less traditional endpoints

| Key findings | YouTube (all patients with AML) | Literature review |

|---|---|---|

|

Appointments and follow-up appointments can be challenging and cause stress for patients Patients expressed the benefits of regional visits from hematologists |

“I’ve refused chemo because it’s not gonna really help me. It’s supposed to… extend my life but I have to be in the hospital for infusions 5 to 10 days a month for the rest of my life. I don’t feel like doing that. I’d rather stay home and have a good life.” “… they gave me a few options another round of chemo, the same type that I had had which I physically was fairly sure I couldn’t handle, the other was a different type of chemo where you get chemo for 5 consecutive days then you’d have 23 days off … the other two options, clinical trial… or the last one was hospice, and none of those options really at the time seemed palatable to me. The only one that had any inkling to me of the possibility, because I could do it locally, was the 1 hour a day for 5 days 23 off and then you do it again. I went through that regimen twice.” |

“Oh God what is he [the consultant] going to say, that blood test, you know, it’s slowly moving back up again and is he going to tell me, ‘well, we need to do something now, you know what I mean, so just that, then I go in and he says whatever, whatever and he talks about it and there’s no need to do anything; oh alright, then, I’ll see you, I’m going.” (patient with MM or ALL) [40] “I just feel that it controls my life with all the hospital appointments and you can’t sort of, I feel like, you can’t PLAN because I have to plan around the appointments and plan around this thing in the back of your mind.” (patient with MM or ALL) [40] “By the time you drive down to the hospital and run around to your appointments, it’s a lot of work …” (patient with AML) [37] “I was devastated when they said you’re going to have to go down to Brisbane for a month in hospital. So I don’t have to go to Brisbane for my follow up; my oncologist comes up here and I’m so lucky. And I can just drive 15 min. Not that I hate being in Brisbane; things were great there but that’s not where I want to be. I want to be with the family. And that was a big trade-off last year, being away from them. Missing out on their lives, you know. Then I didn’t see them for 15 months …” (patient with AML, CML, ALL, CLL, APL, NHL or Hodgkin disease) [50] “It was because I had my home here and I was very tired and all I wanted to do was have the treatment and come straight back home.” (patient with AML, CML, ALL, CLL, APL, NHL or Hodgkin disease) [50] “I don’t know why these, these follow-up appointments, cannot be done locally. Dr X is at Hospital X, has a clinic at the Hospital X, he knows mycosis. X [patient] could have gone there and Dr X would look to see the results of the treatment and know the itching is still going on and could have emailed Dr Y. That would have taken an hour at the most. And to me that’s the failing of having, um, these centers of excellence. Come on, it’s great for the, the, the doctors, it’s great for the research, but it’s hell for the patients.” (patient with CTCL) [34] |

|

Patients discussed the likelihood of their remaining years being spent at hospital receiving chemotherapy Caregivers reported distress at the inappropriateness of their loved one dying (or being cared for) in a ‘large, institutionalized’ setting |

“I wonder sometimes if I live 7 years, if I live 10 years, how much of that will I be involved in just coming for chemotherapy.” (patient with MM) [36] “The treatment … required him to stay in hospital until (date), so it was a long time in jail.” (patient with NHL, AML, CML, ALL or CLL) [49] |

|

| Caregivers explained that they were often reluctant to make plans | “… we do have arguments, because of the things I say to [partner]. Like [partner] will plan a holiday; I don’t plan ahead, you know, [partner] will plan a holiday and I’ll refuse to go. I think it’s mainly because I don’t want to leave my security blanket, like if he took me abroad, I’d feel like I was going away from my security blanket, and my security blanket is [hospital].” (patient with MM) [43] | |

| The value and challenges of hospice care | “… a family again, rather than carers, and that was much better for us, it helped us enjoy Eamon to the very end and it helped us cope better afterwards.” | “The blocking point for us is that often there is no bed in the hospice, or they can’t deal with transfusion needs.” (patient with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma) [47] |

| The threat of infection left patients feeling “trapped” in the hospital or their own home |

“And then after other chemo treatments, having no immune system and basically living at home in what I called “my bubble,” so I couldn’t really go anywhere, and being kinda the season where everybody’s sick, a lot of times I couldn’t see anybody, and that was hard ‘cause I do like … I like to be busy, I like to be out and socializing and doing stuff.” (patient with AML) [37] “I wasn’t prepared. I thought, ‘well, this is outpatient, it’s going to be 4 days of chemo, 1 day of hydration, it will be a walk in the park.’ But with those infections lying there, waiting to come back …”(patient with AML) [38] |

|

| Managing side effects |

“I did notice my hair starting to fall out, so I thought I was mentally prepared for that but I guess I’m not, but that’s okay it’s another hurdle I’ll get over.” “Today was a bad day though, today is when everything hit me, my counts dropped drastically, I’m nauseous, very bad runs erm, extremely tired to the point where I don’t even want to get out of bed, but they make me, but again for everything that ails you, they’ve got something that you can take to fix it.” |

For some of the papers, participants who had non-hematologic cancers (n = 3) were also included; however, all papers reviewed contained at least one participant with a hematologic cancer in the study population

ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, APL acute promyelocytic leukemia, CML chronic myeloid leukemia, CTCL cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, MDS myelodysplastic syndromes, MM multiple myeloma, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Treatment offered at local centers generally helped patients to live a normal family life and minimized the burden to their families associated with extensive and frequent hospital stays. Furthermore, treatment at local centers was beneficial for patients who did not have caregivers or patients with caregivers who were unable to support them through treatment [50]. In some articles, patients expressed concern that most of their remaining time would be spent in a hospital or institution [36, 49]. However, in both data sources, some patients highlighted the value of hospice care in terms of reducing the burden on caregivers. Among patients with AML in the YouTube videos, treatment to counteract side effects was highlighted as a key aspect of managing their condition. Other aspects of treatment commented on by patients with hematologic cancers in the literature review were transfusion dependence and the threat of infections. Both outcomes caused patients to feel trapped either in the hospital or their home [37–39, 46, 47].

Intensive Chemotherapy vs. Non-intensive Chemotherapy or Palliative Care

Some articles and YouTube videos reported findings from an intensive chemotherapy vs. non-intensive treatment perspective [33, 40, 41, 46–48, 51, 54]. One article, focused on treatment decision making in patients with AML who were aged > 60 years, reported that patients choosing intensive chemotherapy were significantly younger than those who opted for non-intensive treatments (median age: 66 vs. 76 years; p = 0.01) [51]. Furthermore, patients who chose intensive chemotherapy were more likely to report having their treatment decisions influenced by their physician [51]. In the YouTube videos, there were some differences between the intensive chemotherapy patient/caregiver posts and those posted by patients/caregivers of patients receiving non-intensive chemotherapy or palliative care. The foci of posts from the intensive chemotherapy group centered on the positive aspects of living longer; specifically, the return to normal family life, resuming work life, being able to travel, and being able to help other people. In contrast, patients receiving non-intensive chemotherapy/palliative care accepted their prognosis, felt death was inescapable, and treatment was only prolonging the inevitable.

Discussion

These analyses had originally aimed to focus on patients with AML, but because of the limited availability of published literature within AML, the literature review was expanded to include other hematologic cancers. Both the literature review and YouTube video searches yielded valuable and informative insights on the patient experience and perceptions of hematologic cancers, in particular for AML. There was a large overlap in the key messages and concepts reported by patients using each approach, thus supporting the value of social media searches as a supplement to traditional research methods.

Although patients and caregivers were cognizant of the terminal prognosis of their cancer, most were focused on the possibility of identifying life-extending treatments that would give the patient the opportunity to reach personal milestones and attend family events. Although many patients and caregivers reported a drive to continue living by using any treatments available, other patients were more accepting of their prognosis. The latter group wanted to enjoy their remaining time without the disruption of treatment regimens or the detrimental impact of treatments on HRQoL.

Many patients expressed their worries and frustrations regarding the lack of treatment options and/or a clear treatment pathway, the possibility of side effects, and how their diagnosis and any treatments would affect their relationships, daily lives, and ability to complete certain tasks. The convenience of treatment center locations emerged as a key factor for patients and caregivers—provision of a facility that would allow patients to live a normal life with their family and in close proximity to hospital was considered highly advantageous for patients. Although data were limited, the results highlighted some differences between patients eligible for or receiving intensive chemotherapy vs. those who were not. In general, patients choosing intensive chemotherapy were younger (median age: 66 vs. 76 years; p = 0.01) [51], were more likely to report having had treatment decisions influenced by their physician, and were more focused on the positive aspects of living longer, such as added time with loved ones. Further investigation of the differences in views between patients receiving intensive chemotherapy vs. non-intensive chemotherapy/palliative care will be crucial to understanding treatment decision making from the patient and physician perspective. Because patient choice and treatment objectives are of paramount importance in selecting therapies, establishing patient perspectives on non-intensive chemotherapy/palliative care vs. intensive chemotherapy could improve patient education surrounding treatment options, the treatment pathway, and supportive care.

The patient perspectives gained in the current analyses support the findings from prior studies exploring perspectives and HRQoL among patients with AML, as well as the insights from patient advocacy groups [16–18, 58]. A common theme in the current study was that the emotional/psychological effect of the diagnosis can have a large impact on the patient, their relationships, and their everyday lives. Other common factors that featured heavily were treatment decision making and the impact of treatments, particularly side effects and the aggressiveness of treatments. In many clinical trials and treatment decisions in clinical practice, there is still a focus on survival as the primary objective of treatment, as opposed to other, less traditional endpoints valued by patients. Treatments that lead to a small increase in overall survival may not be perceived as being efficacious from a clinical, regulatory, or payer perspective; however, prolongation of life, even if only by a few months, is important to many patients. Furthermore, the current analyses showed that patients were willing to accept side effects to potentially prolong life; however, this needed to be considered alongside the patients’ desire to retain a normal life and spend time with family/friends, as well as the impact of treatment schedules, the availability of supportive care medication, and the location of treatment centers. Further understanding these insights into patient perspectives and the patient experience could aid discussions between clinicians, patients, and their caregivers regarding treatment decisions, patient management options, and supportive care.

Given the recent US Food and Drug Administration guidelines [22] and the increasing use of social networking websites as a platform to disseminate experience-based information [21], this approach of combining a targeted literature search with a social media review is both novel and timely. The utilization of YouTube for conveying health information and information pertaining to medical treatments has been previously explored in a number of other therapy areas, such as cardiovascular conditions, prostate cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease, with varying results [26–31]. However, none of these studies specifically explored whether YouTube searches could be used as a method for collecting patient-centered information to gain insight into the patient disease and treatment experience.

Patient experience data provide an opportunity to explore patients’ perspectives on current and potential treatments, with broad clinical, scientific, and regulatory ramifications [20, 22]. Furthermore, patient-reported information shared on social networking websites, such as YouTube, provides access to unsolicited, publicly available data that can be used to gain insight into the patient experience in the rare and orphan disease setting. In the absence of published literature, these data can inform clinicians, healthcare providers, and payers on the perceptions and needs related to treatments [21]. Gaining patient narratives on the expectation, tolerance, and attitudes towards treatments can enhance clinical management decisions, especially in conditions where there is no clear prescribed treatment pathway, e.g., AML and other hematologic cancers. This contextualization has the potential to guide medical product development by highlighting outcomes of importance to patients, leading to improved clinical trial enrollment and retention, and more informed discussions with payers and regulatory agencies [20–22].

In some countries, patient-reported outcomes are becoming increasingly important in reimbursement decision making; however, these can often focus on the proximal signs of disease (e.g., symptoms) and general HRQoL. Therefore, it will be critical to ensure that broader outcomes and patient-reported information are incorporated into clinical trials and that more efforts are made to educate clinicians, healthcare providers, and payers on the patient experience and patient-reported information, and how they can add value to healthcare and reimbursement decision making [59]. For example, when reviewing clinical data, clinicians, payers and/or regulatory agencies may not view an increase in overall survival of a few months as being clinically meaningful; however, therapies that could potentially extend life were of high importance to many patients. For patients with terminal prognoses, treatment decisions are based on a careful assessment of potential life expectancy, QoL, and financial burden that is specific to the circumstances of individual patients and their families, e.g., a short-term gain in survival may allow the patient to achieve certain milestones. Therefore, it is important for clinicians, payers, and agencies to be aware that shared decision making and discussions on QoL are highly personal, and these decisions should be less focused on statistical probabilities and more focused on patient preferences and values [60]. As decision makers, regulatory and reimbursement agencies increasingly rely on multi-criteria decision analysis frameworks, the ability to gather and compile meaningful patient-centric input is poised to become instrumental to achieve holistic healthcare decisions that are both scientifically robust and societally acceptable [61].

The combination of a targeted literature review with YouTube data is a novel approach to obtaining patient perspectives in hematological cancers, and in particular, AML; however, there are a few limitations to these analyses. Of the articles reviewed in the targeted literature search, a limited number focused on older adults with AML, a particular population of interest. As such, the search had to be widened to all patients with AML; however, this approach helped to provide a wider context and understanding of the condition. Additionally, the articles reviewed were published from 1986 to 2018 and therefore some of the reviewed articles may not reflect current opinion on treatment options for patients with AML. The treatment landscape for AML has changed significantly in recent years and continues to evolve (with the approval of five new drugs in 2017–2018); therefore, it is unlikely these treatments were captured in the reviewed articles and YouTube videos. This highlights the evidence gap and unmet need for this type of research to reflect the current management of patients with AML, and illustrates that patient perspectives on these newly approved therapies should be a target for future studies. Three of the articles were conference abstracts and not full journal articles, thus limiting the level of information to be extracted.

Furthermore, there are some limitations to using social media: data are unsolicited and not generated to answer specific research questions. However, this could also be perceived as a strength in that they highlight the most important aspects of the patient experience and are free from research bias. The content is also not regulated or peer reviewed, and users can upload any content they choose, i.e., relevant content is often embedded within irrelevant narratives. In addition, YouTube does not allow for the implementation of a sophisticated or comprehensive search strategy, thus the researcher is limited to searches using simple search terms or simple Boolean operators that may or may not identify all relevant content. There are also limitations in terms of sampling, particularly self-selection bias and reliance on patient self-identification and diagnosis, which may not be verifiable. Patient-reported age was not always available, thus the use of a researcher-determined lower age boundary (i.e., 60 years) could be open to error. However, steps were taken to minimize this researcher bias as far as possible by using two independent researchers to determine a lower age boundary and a third researcher to resolve any disagreement. The quantity of data may be limited following review and may only be from a select group of individuals; however, this is a consequence of the unsolicited and spontaneous nature of the data. Additionally, content may be removed from YouTube because of copyright issues, upon the creator’s request or by caregivers when the patient has died. Furthermore, different social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) are used by different demographic groups, and there may be a potential bias toward younger patient populations who are more engaged with social media platforms.

Although there are limitations associated with the use of social media, it still offers valuable data sources that can provide snapshots into patient priorities and longitudinal data on the patient-lived experience that may not be captured by traditional methods, e.g., interviews and surveys. Furthermore, YouTube has several advantages as a source of data: data are easily accessible, patient-reporting burden is negligible, there is a lack of interviewer bias, and there are minimal recall issues. Additionally, social media is an existing source of data generated independently by individual users; it does not have the resource burdens typically associated with more traditional data collection methods (e.g., face-to-face interviews). This is particularly salient for research concerning patients with rare diseases who may be difficult to access and potentially geographically dispersed. Accessing the patient/caregiver-lived experience of rare diseases via social media can generate initial information to justify the costs of qualitative research, or can provide a valuable adjunct to qualitative research where sample sizes for hard-to-reach populations are likely to be small.

Conclusions

In summary, these analyses support the value of YouTube video searches as a supplement to a targeted literature review. Both analyses provided complementary and valuable information on the patient experience and perceptions of hematologic cancers, in particular for AML. Some treatments may not be considered efficacious from a clinical, regulatory, or payer perspective, as they only confer small increases in overall survival, but they may be clinically meaningful to patients because they allow the patient to have additional time with their loved ones and to achieve life milestones. The patient experience is complex and multifactorial, thus patient management and treatment decisions in clinical practice need to reflect the expectations, goals, and preferences for a given individual. This is particularly true in rare disease/orphan indications and conditions with no clear prescribed treatment pathway, where patient-reported information can contextualize joint treatment decisions made by patients and their treating physicians, enhance clinical management/guidelines and payer decision making, and inform medical product development, including providing input into clinical trial design and interpretation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Megan Latham for her assistance with the targeted literature review. Medical writing support was provided by Anne Marie McGonigal, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions, and funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the trial conception/design, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors contributed equally to the creation of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

These analyses were sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Conflict of interest

Rebecca Crawford, Rebecca Conroy, and Lynda Doward are employees of RTI Health Solutions, which received funding from Pfizer Inc. for these analyses. Timothy Bell, Verna Welch, and Francois Peloquin are employees of Pfizer Inc. Chloe Johnson, Kate Sully, and Adam Gater are employees of Adelphi Values, which received funding from Pfizer Inc. for these analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to data collection, an institutional review board committee reviewed the YouTube study and determined that the social media review did not constitute research with human subjects. Ethics approval was deemed unnecessary as the study data were located within the public domain. Ethics approval was not required for the literature review study.

Data availability

The datasets generated from YouTube and targeted literature review resources and analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Crawford, Email: rcrawford@rti.org.

Kate Sully, Email: kate.sully@adelphivalues.com.

Rebecca Conroy, Email: rconroy@rti.org.

Chloe Johnson, Email: chloe.johnson@adelphivalues.com.

Lynda Doward, Email: ldoward@rti.org.

Timothy Bell, Email: timothy.j.bell@pfizer.com.

Verna Welch, Email: Verna.Welch@pfizer.com.

Francois Peloquin, Email: Francois.Peloquin@pfizer.com.

Adam Gater, Email: adam.gater@adelphivalues.com.

References

- 1.De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e441. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finn L, Dalovisio A, Foran J. Older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: treatment challenges and future directions. Ochsner J. 2017;17:398–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell JA, Galaznik A, Huelin R, Stokes M, Guo Y, Fram RJ, et al. Effectiveness and safety of therapeutic regimens for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic literature review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:e303–e314. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett A, Wetzler M, Löwenberg B. Therapeutic advances in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:487–494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower H, Andersson TM, Björkholm M, Dickman PW, Lambert PC, Derolf AR. Continued improvement in survival of acute myeloid leukemia patients: an application of the loss in expectation of life. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e390. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhayat F, Das-Gupta E, Smith C, McKeever T, Hubbard R. The incidence of and mortality from leukaemias in the UK: a general population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:252. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juliusson G, Antunovic P, Derolf A, Lehmann S, Mollgard L, Stockelberg D, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia: real world data on decision to treat and outcomes from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Blood. 2009;113:4179–4187. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-172007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maynadié M, Girodon F, Manivet-Janoray I, Mounier M, Mugneret F, Bailly F, et al. Twenty-five years of epidemiological recording on myeloid malignancies: data from the specialized registry of hematologic malignancies of Cote d’Or (Burgundy, France) Haematologica. 2011;96:55–61. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.026252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsunaga T, Yamashita K, Kubuki Y, Toyama T, Imataki O, Maeda K, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia in clinical practice: a retrospective population-based cohort study in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. Int J Hematol. 2012;96:342–349. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah BK, Ghimire KB. Improved survival among older acute myeloid leukemia patients: a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:935–938. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.889851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osca-Gelis G, Puig-Vives M, Saez M, Gallardo D, Lloveras N, Guardia R, et al. Is survival in myeloid malignancies really improving? A retrospective 15-year population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:896–902. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.947610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thein MS, Ershler WB, Jemal A, Yates JW, Baer MR. Outcome of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: an analysis of SEER data over 3 decades. Cancer. 2013;119:2720–2727. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oran B, Weisdorf DJ. Survival for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a population-based study. Haematologica. 2012;97:1916–1924. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yogaparan T, Panju A, Minden M, Brandwein J, Mohamedali HZ, Alibhai SM. Information needs of adult patients 50 or older with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1288–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alibhai SM, Breunis H, Timilshina N, Brignardello-Petersen R, Tomlinson G, Mohamedali H, et al. Quality of life and physical function in adults treated with intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia improve over time independent of age. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korol EE, Wang S, Johnston K, Ravandi-Kashani F, Levis M, van Nooten F. Health-related quality of life of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic literature review. Oncol Ther. 2017;5:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s40487-016-0039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant AL, Deal AM, Battaglini CL, Phillips B, Pergolotti M, Coffman E, et al. The effects of exercise on patient-reported outcomes and performance-based physical function in adults with acute leukemia undergoing induction therapy: Exercise and Quality of Life in Acute Leukemia (EQUAL) Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:263–270. doi: 10.1177/1534735417699881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Nooten F, Korol EE, Levis M, Ravandi-Kashani F, Wang S, Johnston K. Health-related quality of life of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic literature review. Value Health. 2016;19:A160. doi: 10.1007/s40487-016-0039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsythe A, Kwon CS, Bell T, Smith TA, Arondekar B. Health-related quality of life in acute myeloid leukemia patients not eligible for intensive chemotherapy: results of a systematic literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;11:87–98. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S187409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, Schrandt S, Frank L. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1581-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin M, Spong A, Doward L, Gnanasakthy A. Patient-reported outcomes, patient-reported information: from randomized controlled trials to the social web and beyond. Patient. 2011;4:11–17. doi: 10.2165/11585530-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: collecting comprehensive and representative input. Guidance for industry, Food and Drug Administration staff, and other stakeholders. Draft guidance. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM610442.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2019.

- 23.McDonald L, Malcolm B, Ramagopalan S, Syrad H. Real-world data and the patient perspective: the PROmise of social media? BMC Med. 2019;17:11. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1247-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothman M, Gnanaskathy A, Wicks P, Papadopoulos EJ. Can we use social media to support content validity of patient-reported outcome instruments in medical product development? Value Health. 2015;18:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarrier KP, Bull S, Fleming S, Simacek K, Wicks P, Cella D, et al. Concept elicitation within patient-powered research networks: a feasibility study in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health. 2016;19:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HM, Hu ZK, Zheng XL, Yuan ZS, Xu ZB, Yuan LQ, et al. Effectiveness of YouTube as a source of medical information on heart transplantation. Interact J Med Res. 2013;2:e28. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok TM, Singla AA, Phang K, Lau AY. YouTube as a source of patient information for varicose vein treatment options. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2016.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pant S, Deshmukh A, Murugiah K, Kumar G, Sachdeva R, Mehta JL. Assessing the credibility of the “YouTube approach” to health information on acute myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35:281–285. doi: 10.1002/clc.21981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg PL, Wason S, Stern JM, Deters L, Kowal B, Seigne J. YouTube as source of prostate cancer information. Urology. 2010;75:619–622. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang W, Olscamp K, Choi SK, Friedman DB. Alzheimer’s disease in social media: content analysis of YouTube videos. Interact J Med Res. 2017;6:e19. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JL, Frey M, Frey P, Hollin IL, Wu AW. Seeing is engaging: vlogs as a tool for patient engagement. Patient. 2017;10:267–270. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0215-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridges JF, Oakes AH, Reinhart CA, Voyard E, O’Donoghue B. Developing and piloting an instrument to prioritize the worries of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:647–655. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S151752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boucher NA, Johnson KS, LeBlanc TW. Acute leukemia patients’ needs: qualitative findings and opportunities for early palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selman LE, Beynon T, Radcliffe E, Whittaker S, Orlowska D, Child F, et al. ‘We’re all carrying a burden that we’re not sharing’: a qualitative study of the impact of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma on the family. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1581–1592. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]