Abstract

Background

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that treatment with metformin be considered for prevention of type 2 diabetes in persons with prediabetes. However, metformin use outside the setting of diagnosed diabetes in US adults is not well characterized.

Objective

To examine trends in self-reported prediabetes and treatment with metformin. We also compared characteristics of adults self-reported prediabetes who were vs. were not taking metformin.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Participants

Adults ≥ 20 years of age who participated in the 2005–2014 National Health and Nutrition and Examination Survey (NHANES), n = 28,461.

Approach

We characterized trends in self-reported prediabetes and metformin use in this population. We used multiple logistic regression models to identify predictors of metformin use among adults with self-reported prediabetes. All analyses accounted for the weighted complex survey design to generate nationally representative estimates.

Key Results

The prevalence of self-reported prediabetes increased from 5.1% in 2005–2006 to 7.4% in 2013–2014 (P-for-trend < 0.001). In persons with self-reported prediabetes, metformin use increased, from 2.4 to 8.3% (P-for-trend = 0.013). Adults who were taking metformin were more likely to be obese and to report trying to lose weight in the past year.

Conclusions

Self-reported prediabetes has increased in the past decade. Metformin use in the setting of prediabetes has also increased but remains relatively uncommon at 8% in adults who self-report prediabetes, despite current clinical recommendations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05398-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: diabetes, epidemiology, guidelines, prevention, population health

INTRODUCTION

Prediabetes is a major public health challenge in the USA and globally1,2 and is associated with substantial risk of progression to type 2 diabetes and other adverse clinical outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and kidney disease.3–5 Population-based studies have established trends in prediabetes based on biochemical definitions (fasting glucose, HbA1c, and/or 2-h glucose), 1,3,6,7 but have not examined trends in self-reported prediabetes or treatment among individuals who report a diagnosis of prediabetes.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has recommended metformin use for treatment of prediabetes since 2008.8 Current guidelines state that metformin treatment should be considered among individuals with prediabetes who are < 60 years of age, have a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2, or a prior diagnosis of gestational diabetes.8 These recommendations are based on evidence for the effectiveness of metformin for diabetes prevention, primarily from the Diabetes Prevention Program Trial 9 and Indian Diabetes Prevention Program.10

Despite formal recommendations for use of metformin in the setting of prediabetes, evidence from prior studies suggest that metformin use is low outside the setting of a diagnosis of diabetes.7,11,12 A prior study based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found metformin use was < 1% among individuals with prediabetes, defined as meeting any of the three ADA glycemic definitions for prediabetes: an elevation in fasting glucose, HbA1c or 2-h glucose, or history of prediabetes.7 Metformin use is low among individuals who have mild hyperglycemia (e.g., single fasting glucose of 100–125 mg/dL with normal HbA1c), the majority of whom are not aware of having prediabetes. The purpose of our study was to understand the prevalence of metformin use in the context of clinically recognized prediabetes. We conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2005–2014 NHANES to characterize national trends in clinically recognized cases of prediabetes (self-reported) and metformin use in this population. We also compared characteristics of individuals with self-reported prediabetes according to metformin use.

METHODS

NHANES is a cross-sectional, complex survey with interview, examination, and laboratory components administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).13 Participants were selected through a four-stage sampling design.14

We included 28,461 participants ≥ 20 years of age who attended survey visits between 2005 and 2014. Of these, 1743 participants self-reported a history of prediabetes. Among adults with self-reported prediabetes, we estimated the percentage of metformin use after excluding for current pregnancy (n = 39), missing prescription medication information (n = 20), and other (non-metformin) anti-diabetic medication use (n = 77) for an analytic sample of n = 1607.

Definitions of self-reported prediabetes and metformin use

NHANES participants were asked, “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” with the option of reporting “borderline diabetes.” Since 2005, participants have been asked about prediabetes outside of the context of diabetes: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have any of the following: prediabetes, impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, borderline diabetes or that your blood sugar is higher than normal but not high enough to be called diabetes or sugar diabetes?”15 We defined individuals with having self-reported prediabetes if they answered “yes” to the latter question or reported “borderline diabetes” when asked about diabetes.

Prescription medication information was ascertained from the medication questionnaire file. Participants provided medication containers to trained interviewers who entered the names into Lexicon Plus, a database of prescription and nonprescription products available in the US market used by NCHS.16 Using the prescription medication file, we extracted anti-diabetic medication information and isolated metformin use according to the 3-level nested category system of Multum Lexicon.16

Demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, risk factors, and lifestyle

Age, sex, race, education, blood pressure-lowering medication use, cholesterol-lowering medication use, smoking status, history of cardiovascular disease, and family history of diabetes were self-reported during the questionnaire portion of the survey. Individuals reported if they tried to lose weight in the past year. History of any cardiovascular disease was defined as having a history of stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, angina pectoris, and/or myocardial infarction. Waist circumference, height, and weight were measured using standardized protocols during the mobile examination. A waist circumference of more than 40 inches (102 cm) among men and more than 35 inches (89 cm) among women was considered high.17 Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured in whole blood and we used a statistical calibration approach to account for changes in laboratory equipment and methods over time; the methods of which have been described previously.18 Cholesterol measurements were obtained using standardized procedures from a subset of fasting participants during the morning examination sessions. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) measures were also available from the subset of fasting individuals and were calibrated to account for changes in methodology and equipment.18

Mean blood pressure values were calculated among individuals with at least two systolic and at least two diastolic blood pressure measurements. Individuals were considered hypertensive if they had a mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg, a mean diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg, or self-reported blood pressure medication use.19 Individuals were considered as having hypercholesterolemia if they had a total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL or self-reported cholesterol medication use. Estimated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk was calculated using the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Pooled Cohort Equation.20

Physical activity was assessed in accordance with the World Health Organization analysis recommendations for the General Physical Activity Questionnaire, implemented by NCHS beginning in 2007.21 Individuals were defined as meeting aerobic physical activity guidelines if they reported ≥ 600 metabolic equivalents (METS) per week which encompasses ≥ 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity or ≥ 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous-intensity physical activity per week.22

Statistical analyses

We calculated prevalence estimates and standard errors for self-reported prediabetes and metformin use among individuals with self-reported prediabetes for each 2-year survey cycle. P values for linear trends were calculated with linear regression models with 2-year survey cycle as the explanatory variable. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design of NHANES and are representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized US population.23 We used the Taylor series (linearization) method to obtain standard error estimates, in accordance with NCHS recommendations.24

To generate population counts, we followed NCHS recommendations and generated weighted proportions of US adults with self-reported prediabetes by categories of age, sex, and race in the 2013–2014 survey cycle.25 These estimates were then applied to 2013–2014 American Community Survey, which reports US population totals, by the same categories of age, sex, and race. We calculated additional population counts for the number of US adults with self-reported prediabetes who met at least one criterion by the ADA for a metformin recommendation and the number of US adults with self-reported prediabetes who were taking metformin.

We evaluated demographic and clinical characteristics of the overall population of persons with self-reported prediabetes to the subgroup taking metformin. We used logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, and race to identify independent predictors of metformin use among adults with self-reported prediabetes. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

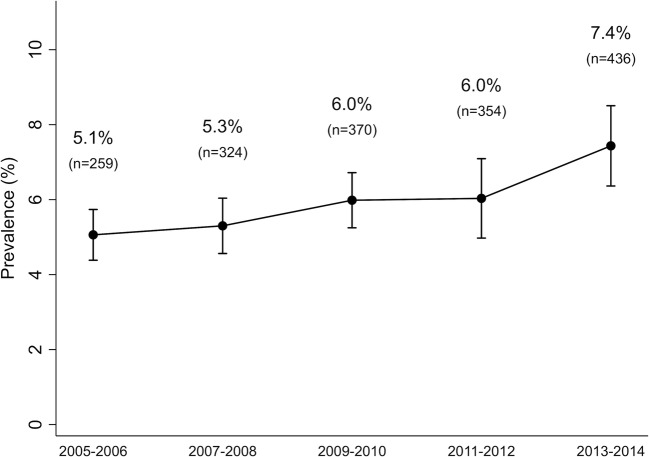

The percentage of US adults ≥ 20 years of age with self-reported prediabetes increased significantly over time, from 5.1% (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.4, 5.7%) in 2005–2006 to 7.4% (95% CI: 6.4, 8.5%) in 2013–2014 (P-for-trend < 0.001; Fig. 1). This corresponded to 17 million adults in the USA from 2013 to 2014.

Figure 1.

Trend in the prevalence of self-reported prediabetes in US adults aged ≥ 20 years, NHANES 2005–2014.

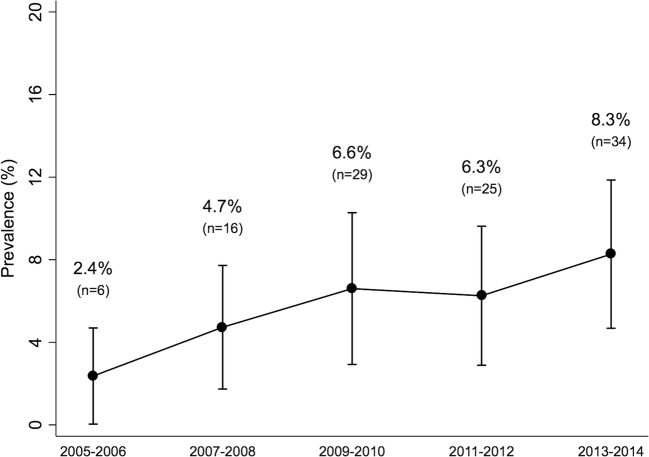

Among those with self-reported prediabetes in 2005–2014, 68.9% (95% CI: 66.0, 71.8%). This corresponded to 11.8 million US adults in 2013–2014 with self-reported prediabetes who met at least one criterion that would merit consideration for treatment with metformin according to ADA guidelines. The prevalence of metformin use among adults with self-reported prediabetes increased from 2.4% (95% CI: 0.04, 4.7%) in 2005–2006 to 8.3% (95% CI: 4.7, 11.9%) in 2013–2014 (P-for-trend = 0.013; Fig. 2). This corresponded to 1.3 million adults with self-reported prediabetes taking metformin in 2013–2014.

Figure 2.

Trends in metformin use among US adults aged ≥ 20 years with self-reported prediabetes, NHANES 2005–2014.

When comparing clinical and demographic characteristics of the total population of adults with self-reported prediabetes with the subgroup of the population taking metformin, adults on metformin were significantly older and had a higher burden of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and elevated 10-year ASCVD risk (Table 1). A high proportion of adults with self-reported prediabetes had levels of hyperglycemia that met the ADA diagnostic criteria for prediabetes. In fact, 8% and 14% met diagnostic criteria for diabetes using HbA1c (≥ 6.5%) or FPG (≥ 126 mg/dL), respectively. Among the subgroup of metformin users, the proportion meeting the definition of diabetes was higher still, with 17% meeting HbA1c criteria and 38% meeting FPG criteria. The percentage of individuals reporting limitations to physical activity and meeting physical activity guidelines were similar between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of US Adults Aged ≥ 20 Years with Self-reported Prediabetes, Overall and Current Metformin Use, NHANES 2005–2014

| Self-reported prediabetes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Overall Mean or % (SE) | Metformin use Mean or % (SE) | |

| Unweighted N | 1607 | 110 |

| Weighted % of the total US adult population | 6.4 (0.2) | 0.45 (0.06) |

| Age group, % | ||

| 20–39 years | 17.0 (1.2) | 13.0 (4.2)† |

| 40–64 years | 56.0 (1.5) | 46.2 (6.6) |

| ≥ 65 years | 27.0 (1.4) | 40.8 (6.7) |

| Male, % | 44.6 (1.8) | 43.0 (6.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||

| Mexican American | 6.4 (0.6) | 7.0 (2.3)† |

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.4 (1.9) | 69.5 (5.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 10.3 (0.9) | 11.4 (3.2) |

| Education, % | ||

| Greater than high school | 60.0 (1.6) | 58.0 (5.9) |

| High school | 23.6 (1.4) | 26.2 (5.4) |

| Less than high school | 16.4 (1.2) | 15.8 (4.0) |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 31.3 (0.2) | 33.5 (0.9) |

| BMI categories, % | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 17.9 (1.0) | 9.0 (2.7) |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 30.6 (1.4) | 24.3 (5.2) |

| 30–34 kg/m2 | 25.4 (1.3) | 23.9 (5.1) |

| ≥ 35 kg/m2 | 26.0 (1.3) | 42.8 (6.0) |

| Mean waist circumference (cm) | 104.8 (0.4) | 112.0 (2.1) |

| Gender-specific waist circumference categories, % | ||

| Low risk | 31.6 (1.2) | 20.5 (4.3) |

| High risk | 68.4 (1.2) | 79.5 (4.3) |

| Mean HbA1c | 5.69 (0.02) | 6.02 (0.10) |

| Categories of HbA1c, % | ||

| < 5.7% points | 57.8 (1.5) | 35.5 (5.4) |

| 5.7–6.4% points | 34.2 (1.5) | 47.3 (5.7) |

| ≥ 6.5% points | 8.0 (0.9) | 17.2 (4.1) |

| Mean fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 108.4 (0.8) | 115.0 (2.9) |

| Categories of fasting glucose, % | ||

| < 100 mg/dL | 36.9 (2.3) | 22.7 (7.8)† |

| 100–125 mg/dL | 48.8 (2.3) | 49.0 (10.1) |

| ≥ 126 mg/dL | 14.3 (1.4) | 28.3 (6.5) |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 49.7 (1.6) | 43.4 (6.6) |

| History of cardiovascular disease, % | 13.8 (0.9) | 19.7 (4.9) |

| Categories of estimated 10-year ASCVD risk, % | ||

| < 7.5% | 66.2 (2.8) | 53.6 (8.0) |

| ≥ 7.5% | 33.8 (2.8) | 46.4 (8.0) |

| Hypertension, % | 65.5 (1.8) | 76.4 (6.2) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 41.6 (2.7) | 53.7 (7.5) |

| Smoking status, % | ||

| Never | 50.2 (1.8) | 41.7 (6.1) |

| Former | 34.8 (1.7) | 43.0 (5.6) |

| Current | 15.0 (1.1) | 15.3 (5.2)† |

| Tried losing weight this past year, % | 51.7 (1.7) | 66.6 (6.1) |

| Physical activity | ||

| ≥ 600 METS/week*, % | 57.6 (1.7) | 56.5 (5.7) |

| Limitations/barriers to activity, % | 9.9 (0.9) | 10.2 (3.3)† |

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; METS, metabolic equivalents; SE, standard error

*Beginning in 2007, NCHS used the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire

†Estimate considered unreliable per NCHS analytic guidelines as the standard error estimate exceeds 30% of the proportion estimate

After adjustment for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, adults with self-reported prediabetes taking metformin were more likely to be obese, have a high-risk waist circumference, and were more likely to have tried losing weight in the past year than those with self-reported prediabetes who were not taking metformin (Table 2). Age, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and elevated 10-year ASCVD risk were not associated with metformin use in adults with self-reported prediabetes.

Table 2.

Prevalence and Adjusted Odds Ratios of Metformin Use Among US Adults with Self-reported Prediabetes, NHANES 2005–2014, N = 1607

| Prevalence of metformin use (SE) | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 20–40 years | 4.5 (1.4) | 1 (ref) |

| 40–65 years | 4.9 (0.9) | 1.28 (0.54, 3.06) |

| 65+ years | 9.0 (1.9) | 2.52 (0.99, 6.41) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 5.7 (1.1) | 1 (ref) |

| Female | 6.1 (1.0) | 1.15 (0.67, 1.98) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5.8 (1.0) | 1 (ref) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6.5 (1.6) | 1.29 (0.65, 2.53) |

| Mexican American | 6.4 (1.9) | 1.36 (0.63, 2.95) |

| BMI category, kg/m2 | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 3.0 (0.9) | 1 (ref) |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 4.7 (1.0) | 1.53 (0.59, 3.98) |

| 30–34 kg/m2 | 5.6 (1.5) | 2.07 (0.92, 4.64) |

| ≥ 35 kg/m2 | 9.8 (2.0) | 4.00 (1.76, 9.08) |

| Waist circumference category | ||

| Low risk | 3.9 (0.8) | 1 (ref) |

| High risk | 6.9 (1.1) | 1.89 (1.02, 3.51) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 5.7 (1.5) | 1 (ref) |

| High school | 6.6 (1.7) | 1.14 (0.52, 2.48) |

| More than high school | 5.7 (1.0) | 1.08 (0.54, 2.16) |

| Hypertension | ||

| No | 4.2 (1.3) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 7.2 (1.1) | 1.39 (0.63, 3.06) |

| High cholesterol | ||

| No | 5.0 (1.3) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 8.2 (2.2) | 1.49 (0.71, 3.09) |

| ASCVD 10-year risk | ||

| < 7.5% | 5.3 (1.2) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥ 7.5% | 9.0 (2.3) | 1.31 (0.75, 2.30) |

| History of cardiovascular disease | ||

| No | 5.5 (0.7) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 8.4 (2.4) | 1.26 (0.70, 2.27) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 4.9 (1.0) | 1 (ref) |

| Former | 7.3 (1.4) | 1.34 (0.78, 2.32) |

| Current | 6.1 (2.2)† | 1.48 (0.58, 3.76) |

| Tried losing weight in the past year | ||

| No | 3.5 (0.6) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 6.5 (1.3) | 2.13 (1.17, 3.90) |

| Physical activity‡ | ||

| < 600 METS/week | 6.8 (1.3) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥ 600 METS/week | 6.5 (1.1) | 1.03 (0.61, 1.76) |

| Family history of diabetes | ||

| No | 6.7 (1.4) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 5.2 (0.8) | 0.75 (0.43, 1.32) |

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; METS, metabolic equivalents; OR, odds ratio: SE, standard error

Statistically significant OR estimates are italicized

*Multiple logistic regression for age groups was adjusted for gender and race; multiple logistic regression for gender was adjusted for age and race; multiple logistic regression for race/ethnicity was adjusted for age and gender; all other multiple logistic regressions were adjusted for age, gender, and race

†Estimate considered unreliable per NCHS analytic guidelines as the standard error estimate exceeds 30% of the proportion estimate

‡Beginning in 2007, NCHS used the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire

The prevalence of self-reported prediabetes was higher in older age (eFigure 1, Panel A) and in adults with higher BMI (eFigure 1, Panel B) but trends were similar in these groups. The prevalence of self-reported pre-diabetes increased over time in all race/ethnicity groups (P-for-trend for all race/ethnicity groups < 0.01), with no significant differences in the prevalence by race/ethnicity during the study period (eFigure 1, Panel C). Nonetheless, clinical characteristics of adults with prediabetes differed by race/ethnicity (eTable 1). Non-Hispanic Blacks and Mexican Americans with self-reported prediabetes had significantly higher body mass indices and higher levels of HbA1c and were more likely to have a family history of diabetes compared with their Non-Hispanic White counterparts. Despite the heterogeneity of HbA1c and cardiometabolic profiles of individuals with self-reported prediabetes by race/ethnicity, there were no differences in metformin use across race/ethnicity.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of self-reported prediabetes and metformin use in the setting of prediabetes has increased in the US adult population, suggesting increases in public awareness, screening, and diagnosis. Among adults with self-reported prediabetes, use of metformin has also increased but remains low despite ADA treatment recommendations.

Factors that may have contributed to the observed increases in self-reported prediabetes and metformin use include increases in true hyperglycemia in the US population1,3 and changes to screening recommendations. In 1996, the ADA guidelines first recommended universal diabetes screening among all adults over the age of 45 to capture diabetes cases among asymptomatic adults.26 In addition, national awareness and attention to prediabetes have increased, especially following the publication of the Diabetes Prevention Program Trial in 2002. In 2010, the CDC announced the National Diabetes Prevention Program, which provides a framework for local programs to achieve national certification.27 The prevalence of obesity in the general US adult population also increased during this period, from 34% in 2005 to 38% in 2014.28 The increase in self-reported prediabetes is likely driven by a combination of increasing prediabetes risk factors as well as increases in public awareness and clinical screening.

Prior national reporting has suggested that there are as many as 85 million US adults with prediabetes.29,30 However, this number does not differentiate between those individuals who are aware vs. unaware of any history of prediabetes. In our study, we found that only 13 million adults self-reported a history of prediabetes. Widely used definitions of prediabetes (any single elevation in a measure of hyperglycemia)29,30 are highly sensitive and may capture many undiagnosed prediabetes cases, some of which would not be clinically recognized or reported back to the patient as “prediabetes.”31

We found that among adults with awareness of a history of clinically recognized prediabetes, metformin use was approximately 8%. Our estimate is comparable with prior studies in clinical settings from 2007 to 2010, which estimated metformin use in prediabetes to be around 10%.11,12 Nonetheless, even in the setting of self-reported prediabetes, metformin use is still relatively uncommon.

We found that half of adults using metformin for prediabetes were over the age of 60 years. Evidence from clinical trials suggest that metformin treatment in older adults with prediabetes may be less effective compared with metformin use in middle-aged adults9,10 and the ADA considers age < 60 years to be a consideration for metformin use.8 Pharmaceutical treatment may be more beneficial for middle-aged adults to delay diabetes onset and prevent long-term progression to microvascular disease 32 Middle-aged adults with prediabetes may warrant more intensive approaches to manage prediabetes and reduce diabetes risk.

A high proportion of adults with self-reported prediabetes had levels of hyperglycemia that met ADA criteria for diabetes. In particular, metformin users were twice as likely to meet the ADA diagnostic criteria for diabetes, compared with the overall group of adults with self-reported prediabetes. The high prevalence of diabetic levels of hyperglycemia among adults with self-reported prediabetes is likely due to progression to diabetes that has not yet been recognized by the patient or provider.

Our study also demonstrates that the adoption of lifestyle modifications even among adults who are aware of their prediabetes history remains suboptimal. Over 80% of all adults self-reporting prediabetes were overweight or obese and only half reported actively trying to lose weight or met physical activity guidelines. Metformin use was common in those who have tried to manage prediabetes through lifestyle modifications. Adults with self-reported prediabetes using metformin were more likely to have tried losing weight within the past year compared with those who were not using metformin.

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, despite our large, population-based sample, there was a relatively small number of individuals with self-reported prediabetes with complete medication information (n = 1607), limiting the precision of our estimates. Second, history of prediabetes was based entirely on self-report and many individuals with clinically recognized prediabetes may be unaware of their diagnosis. Relying on self-reported prediabetes reflects patient awareness but may underestimate the true prevalence of clinically recognized cases due to imperfect recall. Furthermore, it is possible that health care providers may not use the term prediabetes with patients even if laboratory results indicate the presence of an intermediate hyperglycemic state. Lastly, we were unable to assess the proportion of adults with a prediabetes diagnosis who were on metformin for reasons other than prediabetes, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Our study draws upon a number of strengths. NHANES is a nationally representative survey and can provide unbiased, nationally representative estimates. To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate national trends of self-reported prediabetes and metformin use and its correlates in this population.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of self-reported prediabetes has increased in the past decade. Even among adults with awareness of prediabetes, few are meeting physical activity recommendations and the use of metformin remains low (~ 8% of self-reported prediabetes cases) despite current clinical recommendations.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 134 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank NHANES staff and participants.

Funding Information

Elizabeth Selvin was supported by NIH/NIDDK grant K24 DK106414. Kathryn Foti was supported by NIH/NHLBI grant T32 HL007024.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Selvin E, Parrinello CM, Sacks DB, Coresh J. Trends in prevalence and control of diabetes in the United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(8):517–525. doi: 10.7326/M13-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and Ethnic Pattern of Diabetes and Prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Cardiovascular and renal burdens of prediabetes in the USA: analysis of data from serial cross-sectional surveys, 1988–2014. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):392–403. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren B, Matsushita K, Punjabi NM, et al. Comparative prognostic performance of definitions of prediabetes: a prospective cohort analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):34–42. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Cai X, Mai W, Li M, Hu Y. Association between prediabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;355:i5953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James C, Bullard KM, Rolka DB, et al. Implications of Alternative Definitions of Prediabetes for Prevalence in U.S. Adults. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):387–391. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng E, Yeh H-C, Maruthur NM. Metformin Use in Prediabetes Among U.S. Adults, 2005-2012. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(7):887–893. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Supplement 1):S12–S54. doi: 10.2337/dc08-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes With Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. N Engl J Med. 2016;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, et al. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1) Diabetologia. 2006;49(2):289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moin T, Li J, Duru OK, et al. Metformin Prescription for Insured Adults With Prediabetes From 2010 to 2012. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(8):542. doi: 10.7326/M14-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Ward E, Threatt T, Lu ZK. Metformin prescribing in low-income and insured patients with prediabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(4):483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES - Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial - Sample Design. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/Nhanes/SurveyDesign/SampleDesign/intro.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial: Specifying Sampling Parameters: Key Concepts about NHANES Survey Design. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/SurveyDesign/SampleDesign/Info1.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES 2005-2006: Diabetes Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/DIQ_D.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES 2005-2006: Prescription Medications Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/RXQ_RX_D.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 17.Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from shaping America’s health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Associat. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1647–1652. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvin E, Wang D, Lee AK, Bergenstal RM, Coresh J. Identifying Trends in Undiagnosed Diabetes in U.S. Adults by Using a Confirmatory Definition. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(11):769–776. doi: 10.7326/M17-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;71(19):e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES 2007-2008: Physical Activity Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2007-2008/PAQ_E.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019

- 22.World Health Organization P of NDD. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. Available at: www.who.int/chp/steps. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial: STATA Tips. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/nhanes/stata_tips.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial: Variance Estimation: Variance Estimation in NHANES. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/SurveyDesign/VarianceEstimation/Info2.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial: Age Standardization: Task 2c. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/NHANESAnalyses/AgeStandardization/Task2c.htm. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 26.American Diabetes Association. Screening for Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(Supplement 1):S5–S7.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program Standards and Operating Procedures. March 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/pdf/dprp-standards.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 28.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 30.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selvin E, Crainiceanu CM, Brancati FL, Coresh J. Short-term Variability in Measures of Glycemia and Implications for the Classification of Diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1545. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selvin E, Coresh J, Brancati FL. The Burden and Treatment of Diabetes in Elderly Individuals in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2415–2419. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 134 kb)