Abstract

• Engaging a diverse stakeholder group, including patients, clinicians, policy makers, and leadership from national professional organizations as partners in research supports the pursuit of patient-centered outcomes.

• Utilizing the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Engagement Principles and applying adult learning theories to training opportunities can enhance stakeholder-investigator collaborations.

• Regularly scheduled study meetings with stakeholders can help streamline communication, offer a platform for stakeholder voices to be shared, and increase study productivity.

• Ongoing engagement evaluations provide an important opportunity to assess engagement activities and improve processes moving forward.

• Benefits of a robust patient partner and stakeholder body extend beyond the study’s objectives and translate into the creation of larger networks where resources are shared and patient-centeredness is enhanced.

Keywords: stakeholder-engaged research, community engagement, patient partners, patient-centered research, diabetes

1. Background

Recent emphasis on patient-centered outcomes presents a paradigm shift in how health services research is conducted, from a more traditional, top down approach to one that solicits input from various stakeholders (i.e., patients, caregivers, clinicians, policy makers)1. These invaluable contributions help to ensure researchers identify and address questions that matter to patients and other stakeholders and ultimately result in meaningful findings. To this end, the Patient Centered-Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)2–4 formalized the involvement and engagement of such nontraditional research partners throughout the research process, from proposal development to dissemination of study findings5. These partnerships enhance study decisions, improve study design, processes, and outcomes selection, and help keep patient-centeredness at the focus6. Additionally, patients and clinicians agree that partnering can improve both the value of research and the quality of information available for informing treatment decisions7.

Despite widespread support for stakeholder-engaged research, specific activities or practices for encouraging engagement are limited in the literature, variable in nature, and lack comparative data2,3,8–10. This is particularly true for natural experiments, which do not have many of the key phases where engagement activities can feasibly occur as outlined in PCORI’s Engagement Rubric11. While patients and other stakeholders can hold active roles in participant recruitment, informed consent procedures, and prospective data collection in randomized-controlled trials6,12, these phases do not exist in natural experiments. With the growing reliance on electronic health record (EHR) data in research, such as the clinical data research networks (CDRNs) within PCORnet13, it is increasingly important to identify effective approaches to stakeholder engagement in observational studies that may also benefit from stakeholder input.

The purpose of the present paper is to report our framework for the engagement of patient partners and other stakeholders throughout each phase of the PaTH to Health: Diabetes study, an observational study that utilizes the PaTH CDRN. Though we include examples of effective engagement practices in our multi-stakeholder collaboration, this report largely focuses on engagement strategies specific to patients, given their higher level of involvement as partners in the present study. Our evidence-based process may serve as a template for future comparative effectiveness research studies that utilize a CDRN and require stakeholder engagement.

2. Organizational context

The PaTH Network is one of several CDRNs within PCORnet, an initiative of PCORI, which seeks to address questions most meaningful to patients and their communities and to enhance healthcare decision-making through patient-empowered research13. Data Use Agreements and multi-institution partnerships in each network allow for the sharing of health data across sites, resulting in much larger and more diverse populations to study than when working within a single institution. The partnering institutions within the PaTH Network are Geisinger Health System, Johns Hopkins University, Johns Hopkins Health System, Penn State College of Medicine, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Temple Health System, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, the University of Pittsburgh, UPMC and UPMC Health Plan, and the University of Utah. PaTH leverages health-related data from EHRs, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and insurance claims for research purposes. PaTH CDRN has incorporated stakeholder engagement for survey studies and clinical trials. However, our study is the first to utilize the network for a natural experiment, highlighting the uniqueness of the proposed stakeholder engagement.

3. Personal context

Funded by PCORI from 2016–2021, the PaTH to Health: Diabetes study utilizes the novel infrastructure of the PaTH Network to understand the comparative effectiveness of intensive obesity counseling within primary care as covered by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other insurers in improving weight loss for adults either with or at high risk of type 2 diabetes. Recent policy changes provide beneficiaries with obesity up to 20 face-to-face visits for weight counseling in the primary care setting, though service utilization and outcomes are largely unknown. The PaTH to Health: Diabetes study compares weight loss and diabetes outcomes in three PaTH network states (Maryland, Pennsylvania, Utah) using EHR and claims data before and after this policy was implemented.

4. Challenge/Problem

As a PCORI-funded project, our team was challenged to identify meaningful ways of engaging stakeholders in natural experiments, which has not specifically been identified in the literature. Though more traditional research studies have reported engagement strategies6,12, they lack replicability in natural experiments given those phases of research (i.e. recruitment, informed consent) are not included in these designs. Natural experiments are widely recognized as an increasingly important research design in addressing real-world public health concerns due to greater access to more diverse study populations, potentially lower study costs, and faster dissemination of study results14. They are particularly valuable in evaluating policy and determining policy effectiveness where randomization is not ethically or politically possible14. The utilization of EHR data in natural experiments has amplified with the formation of research data networks across multiple health organizations. Funders, including PCORI, support and require the engagement of stakeholders in several types of research, yet there is a paucity of benchmarks for successful stakeholder engagement strategies in observational studies. Failing to identify engagement strategies for natural experiments would be a missed opportunity for patients and stakeholders to shape study design, strengthen outcomes by ensuring patient-centeredness and serve as valuable outlets for dissemination. Establishing best practices for stakeholder engagement in natural experiments is a critical contribution to public health research and would enhance patient-centeredness of results in addressing real-world issues. Therefore, our overall goal was to create a framework for successful research engagement strategies; specific targets were to develop activities for patients and other stakeholders to shape study design, strengthen outcomes, and assist with dissemination.

5. Solution

Assembling a comprehensive stakeholder advisory board that could lend expertise or lived experience to our study was of critical importance and the first step in our engagement process. Patients, clinicians, state agencies, and national patient advocacy and professional organizations (see Table 1) were recruited during proposal development, allowing input at the earliest research stage. Patient partners (n=5) were recruited through primary care provider (PCP) referrals, research listservs, or past/current advisory board membership on other PaTH network studies. Primary care clinician stakeholders (n=6) represent each institution within the PaTH network and serve on the frontlines of addressing obesity clinically. Other community stakeholders (n=10) include leadership strategically selected from relevant government agencies (i.e. Pennsylvania and Maryland Departments of Health) and national organizations (i.e. The Obesity Society and the American Academy of Family Physicians) that share our major focus of quality of care in diabetes and offer important insight into shaping the research and assisting with translation of research findings at regional and national levels.

Table 1.

Stakeholder Advisory Board Engaged in the PaTH to Health: Diabetes Study

| Stakeholder Groups | Rationale for Inclusion |

|---|---|

| Patients (Diversity in race, age, SES, rural/urban) |

Patients are the most experienced in living with the day to day challenges and success of diabetes management and/or overcoming barriers associated with weight loss. Patient partners can ensure the patient voice is present in study design, outcomes selection, and dissemination of patient-centered materials and results. |

| Primary care clinicians Representing all PaTH network institutions (Diversity in rural/urban) |

Primary care is an ideal setting for weight interventions and our clinicians are on the front lines of policy changes for counseling coverage. They can help researchers understand what barriers and facilitators exist to counseling implementation at their respective practices and also translate our study’s findings at the practice level. |

| Hospitals and health systems University of Pittsburgh Johns Hopkins Healthcare LLC |

Internationally-renowned researchers in diabetes offer important insight into shaping the research in all aspects as well as assistance in dissemination. Johns Hopkins Healthcare LLC designs and implements several population health management programs for a variety of diagnoses including diabetes. Preventing diabetes and improving diabetes outcomes are one of their top priorities. Understanding the impact of the state’s decision to expand Medicaid is imperative to informing their future policy decisions and is directly relevant to their mission. |

| Community-based services Pennsylvania Association of Community Health Workers |

This Association represents and supports the largest network of primary care providers in the Commonwealth. They can utilize their far-reaching connections to reach those with or at risk of type 2 diabetes. |

| Policy makers Pennsylvania Department of Health Maryland Department of Health |

Improving diabetes prevention and care for their citizens through various initiatives is a focus of both Departments of Health. Understanding the impact of expanded coverage in these states will be important to inform future policy decisions. They can play a significant role in changes made at the policy level as a result of our study’s findings. |

| National Professional Organizations The Obesity Society American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) |

Professional organizations are well positioned to disseminate our study findings at regional and national levels. The Obesity Society is the leading professional society dedicated to better understanding, preventing and treating obesity and is committed to keeping the medical community and public informed of new advances. The AAFP assists in realizing overall strategies for achieving improved primary care for the nation, uniquely positioning them to serve as a study stakeholder. |

We developed a comprehensive plan to engage patient partners and other stakeholders in all aspects of the PaTH to Health: Diabetes study, from proposal formation through study results dissemination that can be replicated in similar observational studies. Our framework draws from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Engagement Principles (reciprocal relationships, co-learning, partnerships, transparency, honesty, and trust)15 and includes recommended practices for stakeholder engagement from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s recent systematic review16 to ensure meaningful and authentic engagement. Specifically, we have selected patient partners and stakeholders for whom the research has important consequences; prepared them for their roles, responsibilities, and topics being discussed; involved them in each study phase; and provided compensation to support their participation (based on rates of comparable consultants within the region). Drawing from adult learning principles17, we have developed Just-In-Time trainings to provide timely and relevant foundational content for each research phase, decrease knowledge gaps, and strengthen engagement in study discussions. To execute our engagement framework, we dedicated an engagement coordinator to work with patient partners and stakeholders throughout the research process.

5.1. Key Engagement Activities

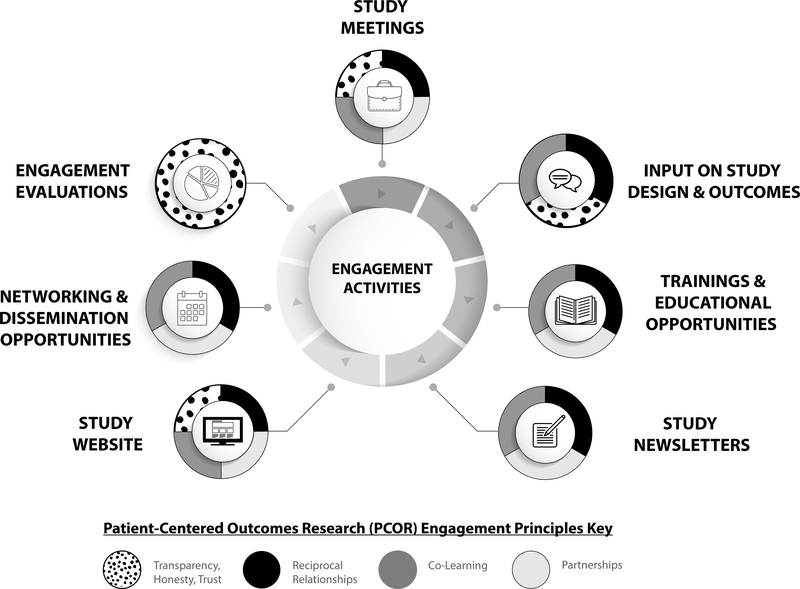

Figure 1 shows the flow of engagement for both patient partners and stakeholders throughout all phases of the research study. Patient partners maintain higher levels of engagement throughout the study (up to 4 hours per month) than other stakeholders (approximately 1 hour per quarter), which is consistent with a previous systematic review3 and speaks to the significant role patients play in driving research towards patient-centered outcomes. Though many of the engagement activities involved patient partners more intensely than other stakeholders, we included opportunities for community and clinician stakeholder feedback at appropriate time points to guide study direction and anticipate peak engagement to occur during study results dissemination. Below are descriptions of key engagement activities and the underlying principles that guided these actionable activities. Further, patient and stakeholder voices, captured through yearly quantitative and qualitative evaluations, have been added as quotations to provide their perspective on various activities.

Figure 1.

Engagement Activities and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Engagement Principles.

5.1.1. Study Meetings

The lynchpin of patient partner and other stakeholder involvement is consistent and clear communication to build trust and maintain transparency in all study decisions. To that end, study meetings are held both in-person (annually) and remotely (monthly for patient partners, quarterly for stakeholders) to advance study objectives, participate in workgroups, and plan for future study milestones. Given the diverse geographic locations in which the team resides, we utilize an online collaborative platform and provide reimbursement for attendance to alleviate burdens associated with participation. To avoid power differentials, we emphasize at the beginning of meetings that each voice has an equal weight at the table, questions and clarifications are welcome, and we will not move forward with a decision until consensus is sought among all research partners. Study meetings also provide the opportunity to share how patient partner and stakeholder feedback, expertise, and voice were applied directly to study activities, demonstrating the co-learning that exists in this collaboration. Our first in-person “study kickoff” conference highlighted the importance of each member’s voice and the process for transparency within our project. The roles of patient partners and stakeholders were collaboratively discussed to demonstrate the reciprocal relationships among research partners, with a focus on expressing commitment to open and honest communication with one another throughout our meetings. These approaches may represent emerging best practices for facilitating engagement across diverse, geographically dispersed team members. “The chemistry on the study team with the other patient partners is wonderful! We have developed that [monthly meeting where] we talk for an hour…I feel like I’ve become a part of their lives.” -Patient Partner #1; “The knowledge that I’ve gained listening into the calls and the experiences that they share, I can go and share that with other people that I know to get them engaged and become proactive in their health and wellness.” -Patient Partner #2. “The quarterly meetings are very helpful as far as the communication and updating and because of my time commitments I couldn’t do a monthly meeting.” -Stakeholder #1.

5.1.2. Input on Study Design & Outcomes

As co-learning is an integral part of this collaboration, stakeholders are empowered to share their insights with researchers, and have meaningfully and significantly shaped study design and outcomes. From the onset during proposal development, stakeholder input was instrumental in re-defining our study outcomes to more patient-centered outcomes. Weight loss was universally considered patient-centered by our stakeholders and our patient partners agreed, knowing the importance this has had in their own lives: “[Before I lost weight] I knew I was on the road to having permanent kidney damage and being insulin dependent [for my diabetes], and that just didn’t feel like quality of life. And I knew I could feel better, that I could still be healthy, and there was still time to do that!” - Patient Partner #3. Further, our patient partners argued that hemoglobin A1c was patient-centered, given its strength as a predictor for diabetic complications: “My numbers [A1c] are important to me… To me, [a good A1c] means I am at my best!” -Patient Partner #4. We recommend similar teams encourage empowerment across all members to enhance study decisions.

During the EHR data extraction phase of the study, patient partners conducted a review of Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) collected at institutions within the PaTH network. The PRO inventory includes several self-report measures (i.e. physical activity, nutrition, sleep) that can be explored as secondary study outcomes. Patient partners offered feedback on which measures to include in analyses and why they are important for our study based on their lived experience with diabetes and/or obesity. These recommendations provide context for prioritizing the statistical analyses, which lends unique perspectives to the data analysis plan and further ensures patient-centeredness of study results. The variety of patient voices among the group, led by the engagement coordinator, provides a safe forum for sharing and decision making. Cultivating a climate of respect and trust is the backdrop for meaningful sharing and an essential component of this type of partnership.

5.1.3. Trainings and Educational Opportunities

As adult learning theory posits that adults are most engaged in training when it has immediate relevance or impact17, we offer timely study-related trainings based on topics our patient partners and stakeholders have expressed interest in learning more about to better prepare them for the current research phase (i.e., data extraction, data analysis, dissemination). The trainings are created for the adult learner, with short (15–20 minute) topics explored through group discussion, scenarios, and roleplay to encourage meaningful discussion and aid in the transfer of knowledge. For example, the Community Partnered Research Ethics Training (CPRET) program18 was an effective way to enhance patient partners’ knowledge of best research practices and ethical considerations specific to our study (i.e. data integrity, data security). Receipt of this training allowed patient partners to be added as official Co-Investigators on the IRB proposal, solidifying their key role on the research team. Additionally, during the data extraction phase of study, training was offered to provide an overview of how EHR data is collected, protected, and used for research purposes via the PaTH network. Patient partners built upon this training by assisting in the development of an educational video illustrating how EHR data can be a powerful way to advance research while emphasizing patient confidentiality. “The video we did on how the data is processed was awesome because it helps us and others understand how patient health data is used in research and how it’s protected.” –Patient Partner #3. Our training program can be tailored to specific study content, making it a feasible approach for other similar studies to ensure the educational needs of a diverse group of partners are sufficiently met.

5.1.4. Study Newsletters

In the letters of support, patient partners collectively shared the same vision for their contribution to the project: to offer their patient perspective and lived experiences with diabetes and obesity. This led to the development of biannual study newsletters, which patient partners play a significant role in crafting, revising, and disseminating to patients with diabetes. Specifically, patient partners identify newsletter components of interest, provide input on resources to include, offer healthy recipes and community event information, review each issue for readability and comprehension, and distribute throughout their communities. Additionally, each newsletter edition features patient partner, stakeholder, and primary care clinician spotlights, as a way to showcase the personal experience and expertise of our entire stakeholder body. “I think that what we’re doing is really good with the newsletters. We’re reaching out to a lot of people who may not have access to good healthcare and letting them know there are different resources out there to help them live better lives.” -Patient Partner #5. Further, stakeholders are helpful in identifying diabetes contacts for newsletter distribution through the various networks or organizations they are affiliated with, expanding the connections we have within the diabetes community for results dissemination and implementation.

5.1.5. Study Website

We have worked alongside our patient partners and marketing team to develop a patient-centered study website, an idea that was generated by them to provide the diabetes community with a resource that describes our study and also covers topics of interest from prevention to self-management of diabetes. Patient partners were instrumental in selecting topics/tools to include, deciding how important information should be shared from a patient perspective, and providing feedback on website structure and flow. This website, www.PaTHDiabetes.org, includes several resource pages such as preventive care information, symptoms checklist, exercise and nutrition tips and tools, diabetes roadmap and management strategies, recipes, study newsletters, and research updates. The creation of this website gives patient partners a platform to directly apply their voice, ideas, and experiences with diabetes, and assists in fulfilling the study’s mission of being patient-centered.

5.1.6. Networking and Dissemination Opportunities

Patient partners and stakeholders are encouraged to represent our study at local, regional, and national events and we expect their level of participation to increase as study results emerge. Two of our patient partners presented alongside research team members at an Annual Diabetes Fair at one of the partnering PaTH institutions, adding immeasurable benefit by connecting the community with our study. When community members approach our table and can hear from another patient who has walked in their footsteps, it creates an immediate dialogue where stories are shared and results in an appreciation of the work we are doing. We also offer opportunities for co-authorship on study manuscripts and have had stakeholders successfully serve in this capacity.

Through the large dissemination network we’ve created for study material distribution in the diabetes community, we have been able to work in synergy with other related studies to reach the same population and avoid duplication of efforts. This has provided opportunity for resource sharing, partnership on shared goals, and broader visibility of research studies.

5.1.7. Engagement Evaluations

We conduct yearly survey engagement evaluations and check-in interviews to provide regular monitoring of engagement and ensure stakeholders feel meaningfully involved. Both forms of evaluation provide opportunities for the study team to assess the effectiveness of engagement activities, determine if we are meeting goals of involvement and maintaining authenticity in our efforts, and improve processes moving forward. Results from past survey evaluations (provided during annual conferences to maximize response rate) indicate patients partners feel most engaged during study meetings, which is reasonable since most of the actual activities and decisions take place during this time. Stakeholders reported that they are able to contribute their ideas in a productive way during study meetings, further demonstrating the importance of having this space for ideas to be shared and decisions made within the group.

To avoid power differentials, the check-ins are facilitated by a community engagement coordinator not involved in the research study and provide opportunity for feedback in a non-threatening environment. Patient partner check-ins are conducted individually while stakeholders participate in a group-check in at the conclusion of a quarterly call to avoid scheduling conflicts. Sample interview questions include: “Do you feel participating in this study is worth your time? Do you feel you have impacted the study and if so, how?” With participant permission, the interviews are recorded and then transcribed with identifiers removed. Thematic analyses from patient partner and stakeholder check-ins indicate that they feel connected to one another and the team, feel valued, and agree they have impacted the study by bringing their voice to the project. “Diabetes is an important topic not only in my life but also my family members so it’s important to me because I’m able to contribute my time and do what I can to help out with the program. It adds value and purpose in what I do, in my life. The knowledge that I’ve gained listening into the calls and the experiences that they share, I can go and share that with other people that I know.” -Patient Partner #1; We’re reaching out to a lot of different people who may not have access to good healthcare and letting them know there are different resources out there.” -Patient Partner #2; “This has been a fascinating process to see how much work went into this massive data collection and the planning for the data analysis. The study team has been amazing in terms of communication and feedback.” -Stakeholder #2.

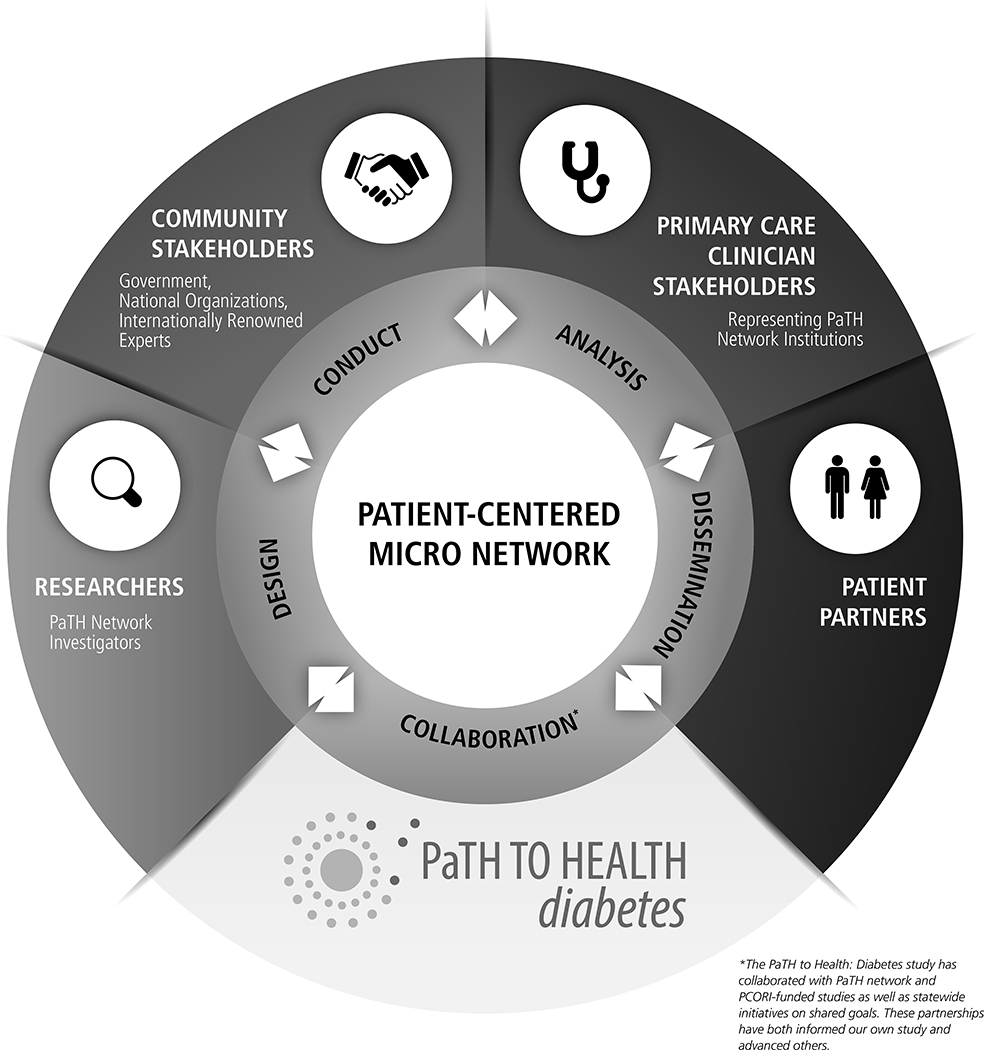

5.2. Micro-Network of Engagement

Our approach to stakeholder engagement in a natural experiment has created a micro-network that shows promising ability in informing our own study as well as partnering and advancing others (see Figure 2). We purposefully formed a diverse and robust collaboration of researchers, stakeholders, and patient partners who are well-positioned to enhance our research and assist in dissemination. Investigators representing each PaTH network institution have lent their expertise and resources within the diabetes community to our study, allowing us to leverage these connections for dissemination of study materials and results. Study stakeholders from government-led agencies and national professional organizations will play a large role in the rapid translation of study findings at the policy and practice levels. This provides a significant advantage over traditional research by decreasing delays commonly experienced in implementation of results. We have weaved patient partner perspectives throughout the design, conduct, and analysis of the study to ensure patient-centeredness remains at the heart of our work. Further, we have partnered with PaTH network and PCORI-funded studies as well as statewide initiatives on shared goals, which has been mutually beneficial.

Figure 2.

PaTH to Health: Diabetes Micro-Network of Engagement.

5.3. Overcoming Engagement Challenges

Technical and process challenges are unavoidable given the lack of any benchmark for stakeholder engagement in an observational study. One challenge we face with the broad range of backgrounds and experiences of our stakeholders is ensuring that we are all “speaking the same language” at project meetings; i.e. researchers explain health outcomes and results in a way patient partners will understand. However, the diverse team allows for a continuous learning process, where each member can gain from the sharing of another’s expertise and experience. The research team also makes a concerted effort to explain study specifics in detail, use analogies when appropriate, and answer any clarification questions. Another ongoing challenge is ensuring stakeholders stay connected and continue to feel engaged. Though previous reports indicate stakeholders are more typically engaged earlier than in later stages of research3, we want them to remain fully engaged so that they make contributions through the dissemination and implementation stages. In the meantime, we continue to draw from their expertise during study meetings and decision-making. A final challenge we face with our group of stakeholders is the varied geographic location in which they reside. However, we have overcome this challenge by utilizing the benefits of remote connectivity for stakeholders and patients to attend trainings, meetings, and share documents.

6. Unresolved Questions and Lessons for the Field

Though content created for or derived from the engagement activities presented were specific to our study, the structure of our approach is widely disseminable to other natural experiments. For example, inviting a diverse group of patients and professionals to our study conversation, empowering them to take ownership in study resources, and providing opportunities for them to actively contribute to results dissemination and community outreach are all approaches that could be replicated in similar studies with patient partner and other stakeholder participation. We encourage future research teams to solicit input from a broad range of community voices to refine study outcomes, strengthen study relevance, and increase uptake of findings.

Offering study meetings on a quarterly remote basis for busy, geographically dispersed stakeholders with an opportunity for annual face-to-face meeting has been a sustainable approach for maintaining connections among the group and overcoming participation barriers. More frequent meeting (monthly) was a decision unanimously reached by patients and the research team, given their higher level of involvement throughout the study. We recommend a similar schedule of study meetings to future groups to enhance communication and maintain engagement throughout the research process. Additionally, having a smaller number of patient partners compared to our larger community stakeholder group proved beneficial in increasing productivity and decision-making on more day-to-day study operations. Meetings and other stakeholder-related activities were led by our team’s engagement coordinator, who ensured the various feedback received from our community partners were incorporated into the study. We encourage future teams to designate a similar liaison between researchers and stakeholders to enhance patient-centeredness of study processes and outcomes.

Our study was limited to engagement evaluations as a formal indicator of engagement success and with only 5 patient partners our qualitative data analysis did not allow for saturation of themes to emerge. Additionally, self-report data on a yearly basis are limited by recall6. More research is needed to further elucidate how engagement impacts study relevance, patient-centered outcomes, and results dissemination2. Identifying measures that quantify stakeholder contributions in enhancing study aims and outcomes would be a considerable contribution to this field. However, process outcomes including high meeting attendance (i.e. 75% attendance or greater at most meetings), diverse representation on study resources and manuscripts (i.e. patients, clinicians, and community stakeholders have contributed to six biannual study newsletters to date; two community stakeholders have served as co-authors on study manuscripts), and greater audience reach through our diverse network for results dissemination support the strength of our engagement approach.

Engaging stakeholders as partners in research supports the pursuit of patient-centered outcomes. The presented framework of engagement is a feasible approach for observational studies that utilize a CDRN and can be tailored to fit the needs of other studies, particularly natural experiments. More research is needed to identify impact of stakeholder engagement in observational studies and specifically on outcomes for patients with or at risk of type 2 diabetes19.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our patient partners for their contributions to this manuscript and their unwavering support in our research (Angela Evans, Julie Tice, Cynthia Bradley, Mully Chea, Treva Alston). We would also like to thank our community and primary care provider stakeholders for their contributions to the PaTH to Health: Diabetes study. Finally, we would like to thank Pamela Witt for conducting the patient partner check-in engagement evaluations and Ellie Hogentogler and Abbey Kinard for their marketing and design assistance.

Financial Support

Research reported in this manuscript was funded through a PCORI Award, NEN-150932304. PCORI had no role in the design of the study, data collection or interpretation, or writing or approving the finished manuscript. This study was funded through a PCORI Award (PCORI CDRN #1306-04912) for development of the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network, known as PCORnet. The authors acknowledge the significant contributions to this study that were provided by collaborating investigators in the NEXT-D2 (Natural Experiments in Translation for Diabetes) Study Two. The authors also acknowledge the participation of our partnering health systems. The project described was partly supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1 TR002014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Engagement evaluation data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and College of Medicine.

Footnotes

All co-authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Selby JV, Forsythe L, Sox HC. Stakeholder-driven comparative effectiveness research: an update from PCORI. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2235–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1692–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patient-centered outcomes research institute. http://www.pcori.org. Accessed January 23, 2018.

- 5.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, Schrandt S, Frank L. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forsythe LP, Frank LB, Workman TA, Hilliard T, Harwell D, Fayish L. Patient, caregiver and clinician views on engagement in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2017;6(3):231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Absolom K, Holch P, Woroncow B, Wright EP, Velikova G. Beyond lip service and box ticking: how effective patient engagement is integral to the development and delivery of patient-reported outcomes. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA. Advisory panel on patient E. the PCORI engagement rubric: promising Practices for partnering in research. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gesell SB, Klein KP, Halladay J, et al. Methods guiding stakeholder engagement in planning a pragmatic study on changing stroke systems of care. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1(2):121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleurence RL, Curtis LH, Califf RM, Platt R, Selby JV, Brown JS. Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):578–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leatherdale Scott T.. Natural experiment methodology for research: a review of how different methods can support real-world research, Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2019;22(1):19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.PCORI. engagement rubric for applicants. 2016; https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf Accessed April 28, 2018.

- 16.Mallery C GD, Fernandez J, Smeeding L, Robinson S, Moon M, Lavallee D, Siegel J. Innovative Methods in Stakeholder Engagement: An Environmental Scan. Rockville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles MS, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner. 12th edn. (Routledge, New York, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonas MA, Jaime MC, Barone J, et al. Community partnered research ethics training in practice: a collaborative approach to certification. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2016;11(2):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmittdiel JA, Desai J, Schroeder EB, et al. Methods for engaging stakeholders in comparative effectiveness research: A patient-centered approach to improving diabetes care. Healthcare. 2015;3:80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]