Abstract

Congenital HCMV infection has been reported to be involved in learning and memory impairment, but whether HCMV IE2 plays a key role in the process remains unknown. The purpose of this study was to study the effects of IE2 on the expression levels of NMDA receptors and CX43 in the hippocampal neurons of ul122 transgenic mice. Firstly, the ul122 genetically modified mice models that can steadily and continuously express IE2 protein were established. Then, the mice were divided into the experimental group (positive mice identified) and the control group (wild type mice. n = 24 in each group). The establishment of ul122 genetically modified mice was identified by PCR technology. The learning and memory ability were measured using the Morris water-maze test. Western blot and immunohistochemical study were performed to detect the expression level of Cx43 and NMDA receptors. The results of PCR indicated that the ul122 genetically modified model was successfully constructed. Morris water maze test result showed that in the experimental group, less platform crossings and Quadrant time (%) compared to the control group, but there was no difference in escape latency. The expression level of Cx43 in the hippocampus CA1 of the experimental group was significantly reduced in keeping with NMDA receptors in immunohistochemistry. The significant decreased expression level of Cx43 and NMDA receptors in the ul122 genetically modified mice hippocampus may be connection with the mechanism for spatial memory impairment.

Keywords: IE2, Cx43, NMDA receptors, hippocampus, spatial memory impairment

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the family Herpesviridae and subfamily Beta herpesvirinae [1]. Its seroprevalence ranging from 40 to 100%, due to difference in age, geographic allocations and socioeconomic status [2]. In the infant, symptoms of HCMV infection are serious, such as microcephalus, epileptic encephalitis, cerebral palsy and optic atrophy. While, infants infected with HCMV congenitally have also showed to have a loss of sensorineural hearing, mental retardation, low deafness and intelligence [3].

HCMV encodes two different viral immediate early proteins, one is immediate early (IE) proteins IE1 and the other is IE2, IE2 encoded by the gene UL122, is the most extensive researched virus genes, owing to its genetic product play a key role in the viral replication, and in the pathogenesis of many diseases. Previous studies have shown that IE2 regulates host gene expression in host cells by direct interaction with cell genes or proteins [4,5]. Some researches indicate that IE2 may be accountable for the host cellular profile [6]. Owning to species specificity, HCMV can only infect human and not be infectious in other creatures [7]. Previous researches on the specific mechanism of which HCMV IE2 play an important role in various diseases of nervous system were carried out in vitro or in rhesus macaques infected with rhesus CMV (RhCMV) representing the animal model that closely resembles humans infected by HCMV. Although MCMV and HCMV genes have higher homology, the study of the function of MCMV in the mice does not equate to the molecular mechanism of HCMV encoded gene products. So, the ul122 genetically modified mice model was established, meanwhile, an organismic internal environment where IE2 can be expressed persistently and steadily was. The establishment of the ul122 genetically modified mice model overcome the species specificity will contribute to expound the mechanism of IE2 inducing diseases, as well as efforts to provide theoretical basis for the prevention and treatment of disease.

Existing as the key area for spatial memory and learning, the hippocampus is located between the cerebral thalamus and the medial temporal lobe, which is part of the limbic system. Recently, a lot of studies have demonstrated that congenital HCMV infection may inhibit the synaptic plasticity of the Sprague-Dawley rats, which could trigger learning and memory dysfunction [8], However, it was not clear whether the IE2 protein expressed by ul122 gene in mice has the same effect as HCMV mechanism. We therefore investigated the effects of IE2 on learning and memory in the ul122 transgenic mouse as well as the mechanisms that affect it. Our findings showed that IE2 plays a key role in the process of spatial memory impairment without affecting learning ability. Among these, hippocampal NMDARs play a significant part in synaptic plasticity and cognitive functions, it influences memory, particularly spatial memory [9-11]. Following the above research, we speculated that it is IE2 that down-regulate the expression level of the NMDARs in normal hippocampal tissue, which impaired the spatial memory.

Gap junctions composed of connexin proteins are membrane channels that play an important role in intercellular communication in the nervous system. Cx43 involved in extensive GJ coupling (GJC) between astrocytes which are the most abundant cell type in the brain are expressed most highly in the brain [12]. In addition, previous research has shown that IE2 promote degradation of CX43 in gliomas [1]. Moreover, Cx43 could activate astrocytes and NMDA receptors in the spinal astrocytic [13,14]. In the study, we also found that IE2 down-regulated the expression of CX43, which may affect activation of the NMDARs, thus, it will provide a new approach for studying IE2 mechanism of spatial memory impairment. This study aims to investigate the important role of IE2 in Cx43 and NMDARs changes in the ul122 genetically modified mice and the effect of this change on spatial memory.

Materials and methods

Animals

Four ul122 genetically modified mice (two months old) involving two female and male were obtained from Laboratory of pathogenic biology of Qingdao University. All animal experiments were authorized by the Animal Experiments Committee of Qingdao University. Four C57 WT mice (two months old) mated with the ul122 transgenic mice randomly and four pairs were divided respectively into four cages kept in such a SPF level of environment. Not keep them apart until female mouse was pregnant. After the DNA extracted analysis of the tails of half a month old mice, the ul122 positive mice were left for the experimental group and the negative as the control. In the end, we obtained 24 ul122 positive and negative mice respectively as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of mice used for a series of experiments followed

| A | |||

|

| |||

| Experimental group | Quantity | Gender | Median weight (range/g) |

|

| |||

| 15 days (young mice) | 8 | 4♂/4♀ | 5 (4-6) |

| 4 months (adult mice) | 8 | 4♂/4♀ | 28 (27-30) |

| 1 year (aged mice) | 8 | 4♂/4♀ | 39 (37-40) |

|

| |||

| B | |||

|

| |||

| Control group | Quantity | Gender | Median weight (range/g) |

|

| |||

| 15 days (young mice) | 8 | 4♂/4♀ | 5 (4-6) |

| 4 months (adult mice) | 8 | 4♂/4♀ | 28 (27-30) |

| 1 year (aged mice) | 8 | 4♂/4♀ | 38 (37-39) |

Extraction of DNA and PCR

The PCR was executed according to the manufacturer’s protocol after DNA was extracted using a DNeasy tissue Kit (TIANGEN). The cycling condition details as follows: Pre-denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec; annealing at 60°C for 35 sec; extension at 72°C for 1 min and further extension at 72°C for 10 min. This PCR cycle was performed for 35 times. The primers’ sequences were 5’-3: CAGTCCGCCCTGAGCAAAGA (Forward) and 5’-3’: TATGAACAAACGACCCAACACCC (Reverse).

Morris water-maze test

Morris water maze test includes orientation navigation and space exploration trials primarily. The water maze equipment included circular tank (diameter: 130 cm, depth: 60 cm) filled with running water (depth: 30 cm, temperature: 25 ± 3°C) and cover with white plastic foam. The pool was divided into four quadrants, in one quadrant center; machine plastic circular platform approximately 2 cm below water surface was placed and kept in the same place during all trials. Camera connected to a computer was placed above the core of equipment. Each experiment was videotaped and the animals’ movement tracked by the computer aided tracking system. A lot of extra-maze cues around the pool were available for the animals such as furniture, equipment, and some geometric Shapes mounted on the wall. All of the above were in the same locations during all the trials. The water maze experiment was conducted in four months old mice and the mice were examined for 7 days including the first six days of orientation navigation and last day of space exploration trial. The mice were trained and recorded six consecutive days in four quadrants. Parameters for the test were time to find the hidden platform in the first six days and average speed, platform crossings and quadrant time (%) in the target quadrant without the platform in the last day.

HE staining of mice hippocampus

The hippocampus of all the mice were isolated, fixed with 4% Citromint and embedded in paraffin. Approximately 1 µm thick sections of the hippocampus tissues were stained with H&E and examined by a light microscope (from Olympus, Japan).

Western blot

The same samples used for detection the CX43 expression levels of hippocampus by immunohistochemistry were also used for Western blot. The hippocampus was collected for protein extraction. All the protein extracts were separated into SDS-polyacrylamide gels then boiled for 5 min. Proteins were transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk powder for 1.5 h at room temperature, then incubation with the primary antibodies overnight (monoclonal antibody IgG of mouse’s CX43). Membranes were washed and incubated with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000) for 60 min. chemiluminescent signals were produced by the SuperSignal West Pico Trial Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was operated on hippocampus in the whole mice after finishing Morris water-maze test. Firstly, one-μm hippocampus sections were placed on charged slides, baked at 70°C one hour, then deparaffinized, rehydrated, and boiling water for two minutes pretreated for antigen retrieval with Sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After cooled to room temperature, washed by distilled water and PBS for 15 min. Endogenous catalase was inactivated with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were then incubated one hour with the primary antibody in the incubator at 37°C. (Anti-Cx43 and anti-NMDARS antibodies diluted at 1:200 and 1:300 respectively, Bioss, Inc.; anti-IE2 antibody diluted at 1:100, Millipore, USA). After washed with distilled water and PBS, sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 40 min. The tissue sections were then exposed to DAB for 1 min and hematoxylin for 2 seconds, and observed after the neutral gum seal.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS software version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The statistical analysis of orientation navigation statistics were performed using analysis of variance of repeated measure. The statistics of space exploration trials, Immunohistochemistry and Western blot were analyzed using Student’s-t test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Extraction of DNA and PCR results of mouse

PCR showed that we extracted ul122 genes from some mice in Figure 1. The mice were divided into the experiment group and control group based on whether ul122 exists or not. The ul122 positive were treated as the experimental group and the negative as the control group.

Figure 1.

Identification of the positive and negative mice by PCR. (Lanes 1-2, 4-8) positive mice, the IE2 gene was extracted from the mice tails. (lane 3) the negative mice, in which IE2 gene was not extracted from the tails. (Lanes +, -) the positive and water control. Transgene PCR product size: 335 bp.

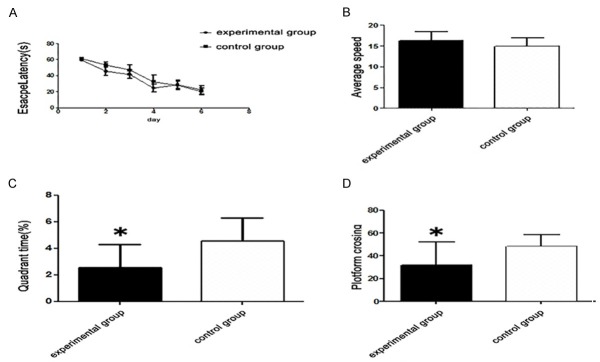

Morris water-maze experiment results

Memory impairment in the ul122 genetically modified mice was determined by the MWM test, as shown in Figure 2. (A) In terms of the escape latency, there was no significant difference between the experimental group and the control group (Figure 2A). On day 7 of the MWM test, the hidden platform was removed from the circular tank, and all mice were allowed to swim for 60 sec in the pool. As shown in Figure 2B, the difference in average speed between the experimental group and the control group was not obvious. In addition, the number of platform crossing was significantly reduced in the experimental group compared with the control group (P<0.05; Figure 2C). Furthermore, the mice in the experimental group spent a decreased amount of time in the target quadrant when compared with the control group (P<0.05; Figure 2D). It suggested that IE2 impaired the spatial memory ability of mice in some degree, but has no influence on learning ability.

Figure 2.

Morris water-maze test results. A. There was no significant difference in escape latency between the experimental group and the control group. B. The difference in average speed between the experimental group and the control group was not obvious. C. The mice in the experimental group showed significantly decreased platform crossing than the control group. D. Quadrant time (%) between the experimental group and the control group was different obviously. (*P<0.05 vs the control group).

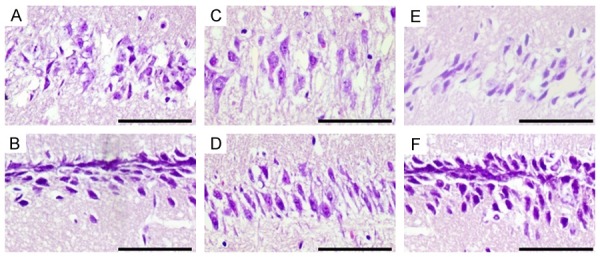

IE2 promoted hippocampal neuron damage in UL122 transgenic mice

The damage of hippocampal neurons in the UL122 transgenic mice was observed by hematoxylin-eosin staining as shown in Figure 3. The arrangement of hippocampal neurons in the experimental group (Figure 3A, 3C, 3E) were disorganized, some neurons were dead as characterized by neurons shrinkage and the intercellular space became larger compared to the control group (Figure 3B, 3D, 3F). Compared with the control group, neuronal damage in the experimental group was obvious, which indicated that IE2 might have a damaging effect on neurons.

Figure 3.

Effect of IE2 on morphological changes in the hippocampal CA1 region of the UL122 transgenic mice. (A, C, E) Morphology in the hippocampal CA1 region of the young, adult and aged mice respectively in the experimental groups. (B, D, F) Were the corresponding control group. Young mice: 15 days after birth; adult mice: 4 months after birth; aged mice: 1 year after birth. Compared with the control group, neurons morphology and the arrangement in the experimental group had obvious abnormalities. Bar: 400 μm.

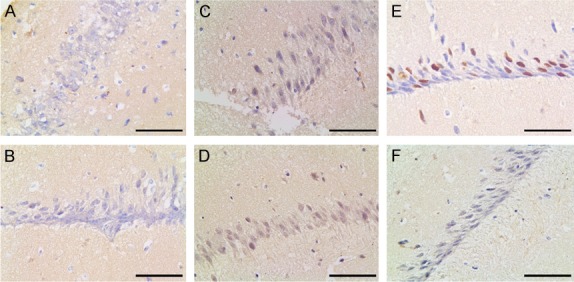

The expression of the IE2 in the hippocampus of young, adult and aged ul122 transgenic mice

IE2 expression was observed by immunohistochemistry in mice hippocampus at three different stages. At 15 days after birth (young), the hippocampal expression of IE2 in the nucleus was so low that can’t be seen in the experimental group (Figure 4A). At 4 months after birth (adult), the nuclear positive was relatively obvious than it at 15 days after birth (Figure 4C). At one year after birth (aged), as shown by immunohistochemistry, nuclear staining was strongly positive. In addition, among the three different stages of mice, the expression of IE2 level in the aged mice of the experimental group was the highest (Figure 4E). Figure 4B, 4D, 4F as the control group. The nuclear staining was all negative.

Figure 4.

IE2 immunohistochemistry in the hippocampus of young (A, B), adult (C, D), and aged (E, F) mice. In the CA1of experimental group, nuclear staining was stronger positive in all layers with age. (A, C, E) Immunohistochemistry for IE2 in the hippocampus CA1 of mice in the experimental group. (B, D, F) The IE2 protein in the hippocampus CA1 of mice in the control group. Compare with young mice (A), the expression of IE2 in adult mice (C) was increased; compare with adult mice, the expression of IE2 in aged mice (E) increased obviously. Bar: 400 μm.

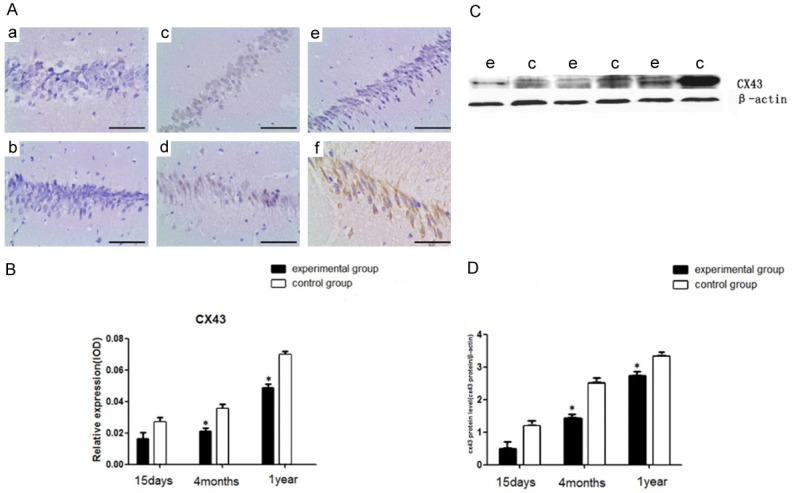

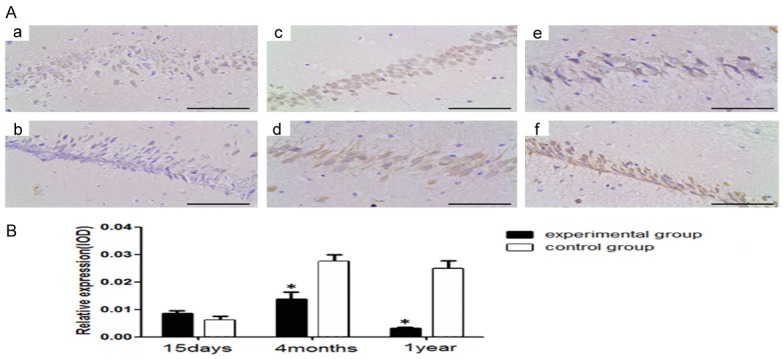

IE2 downregulates Cx43 protein expression in ul122 transgenic mice hippocampus

Cx43 was found to be downregulated by infection with the HCMV laboratory strains in human fibroblasts [13]. To further determine whether IE2 affects the expression of CX43 in normal hippocampal, the expression of IE2 protein in the hippocampus was measured by Immunohistochemistry (Figure 5A, 5B) and Western blot (Figure 5C, 5D) at three different periods after birth. As show in it, in the young mice (Figure 4A), IE2 protein was not yet expressed in hippocampal CA1 and there was no difference in the expression of CX43 in the experimental group and control group. In the adult mice, as known the obvious expression of IE2 protein in the experimental group (Figure 4C), the expression of CX43 in the hippocampus of the experimental group was significantly lower than that in the control group as we saw in the results of the experiment. In the aged mice, the IE2 expression increased (Figure 4E), meanwhile the CX43 expression in the experimental group decreased obviously compared with the control group. In addition, the expression of CX43 gradually increased with age. Those results indicated that IE2 downregulates Cx43 protein expression.

Figure 5.

CX43 immunohistochemistry (A, B) and Western blot analysis (C, D) in the hippocampus of young, adult, and aged mice. (a, b) The young mice. (c, d) The adult mice. (e, f) The aged mice. (B) The relative expression of CX43 in the CA1 region of hippocampus. (C, D) Western blot analysis of CX43 in the CA1 region. (e) The experimental group; (c) The control group. (n = 8 per group; *P<0.05: significantly different from the control group; the bars indicate the means ± SEM). Bar: 400 μm.

IE2 downregulates NR1 protein expression in ul122 transgenic mice hippocampus

Congenital HCMV infection reduces the expression of NMDARS in the hippocampus of SD rats [15]. To further explore whether IE2 affects the expression of NR1 in hippocampal, we measured the expression of NR1 in the young, adult and aged mice by immunohistochemical (Figure 6). As shown in Figure 6, the results indicated that the expression level of NR1 was dramatically decreased in the adult and aged mice of the experimental group compared with that of the control group (P<0.05). All the result revealed that IE2 downregulates NR1 protein expression in ul122 transgenic mice.

Figure 6.

NR1 immunohistochemistry in the hippocampus of young, adult, and aged mice. a, b. The young mice in the experimental group and control group respectively. c, d. The adult mice in the experimental group and control group respectively. e, f. The aged mice in the experimental group and control group respectively. B. The relative expression of NR1 in the CA1 region of hippocampus. (n = 8 per group; *P<0.05: significantly different from the control group; the bars indicated the means ± SEM). Bar: 400 μm.

Discussion

The study concludes that IE2 down-regulated the expression of Cx43 and NMDA receptors. The reduction of NMDARs protein levels in the ul122 genetically modified mice may result from lower expression of CX43. Less platform crossings and Quadrant time (%) was observed in the ul122 genetically modified mice, but there was no significant difference in escape latency. All experimental results indicated that IE2 damage the spatial memory ability, but has no influence on learning ability.

HCMV regulates the secretion and transcription of host cells in order to diffuse it, thus forming a lifelong latent infection [16,17]. The IE2 encoded by ul122 in HCMV is the most extensively studied as it plays an important role in viral replication and has been indicated in the pathogenesis of some diseases [18]. Due to the highly species-specific of HCMV, the study of IE2 is limited to in vitro models of infection and to the study of animal CMVs that coevolved with the species. The construction of ul122 overcome the species specificity and provides an effective way to study the influence of IE2 on learning and spatial memory.

As one of NMDAR subtypes, increasing evidences show that the expression of NR1 protein in the brain infected with HCMV was markedly decreased than that in uninfected brain [8]. This decrease in NR1 could attenuate neuronal responses to glutamate, in this case, glutamate-induced excitotoxicity is suppressed in infected neurons and hippocampal [19]. Previous studies have shown that NMDARs are important in spatial memory and learning ability, especially spatial memory [20]. The NMDARs (NR1, NR2A, and NR2B) play an important physiological role in cognitive functions and synaptic plasticity [10,11]. In addition, Congenital HCMV infection may reduce the range of synaptic plasticity, which may lead to learning and memory impairment caused by congenital HCMV infection during pregnancy [8]. It is not known whether IE2 which was expressed by the ul122 transferred into the mice has the same efforts in vivo as the influence of HCMV infection on NR1 resulting in learning and memory impairment. In the Figure 6, the result showed that the experimental groups which expressed IE2 persistently had a low expression level of NR1 compare with the control group. All the results showed that IE2 downregulates NR1 protein expression in hippocampus, resulting in the spatial memory impairment of the ul122 genetically modified mice.

Cx43 interacts with and modulates the expression of many genes involved in cell cycle control and tumorigenesis [21]. In the central nervous system, astrocytes are the most abundant cells that communicate through gap junctions [22]. Cx43 is the main component of astrocytes gap junctions [23]. some Related research shows that IE2 promote degradation of CX43 in gliomas [1]. However, whether the IE2 which encoded by the ul122 induces the degradation of CX43 in the ul122 genetically modified mice is still incompletely clear. Accumulating evidence indicates that Cx43 has been involved in activation of NR1 by chronic morphine [13,14]. The astrocytic Cx43 regulates the functional activity of NMDA receptors by regulating the GLT-1 expression [24]. Blocking the spinal Cx43 with Gap26 inhibited increase in expression and phosphorylation of NR1, indicating that the Cx43 may contribute to increased activation of NR1 [14]. In the ul122 genetically modified mice, owing to the expressions of NR1 and CX43 decreased in synchrony (Figures 5, 6), we proposed that IE2-Cx43-mediated NR1 may represent a novel mechanism underlying the mechanism for spatial memory impairment in the ul122 genetically modified mice. We speculated that there might be a signaling pathway to modulate the expression of NR1. That is, Long-term stable expression of IE2 in the ul122 genetically modified mice-induced reduction in Cx43 Inhibits the activation of astrocytes and reduction of extracellular glutamate uptake by up-regulation of the GLT-1 expression, finally resulting in reduction of NR1. However, the mechanisms of the IE2- Cx43-mediated NR1 in the development of spatial memory impairment are complicated and require further studies.

To evaluate the effects of IE2 on CX43 and NR1 expression in vivo, the ul122 genetically modified mice were constructed. We found that IE2 significantly down-regulated CX43 and NR1 in the ul122 genetically modified mice. Moreover, the expressions of NR1 and CX43 decreased in synchrony. Mice in the experimental group showed impaired spatial memory. These findings suggest that a NR1-mediated role involving Cx43 in spatial memory impairment. In conclusion, we’ve come to the conclusion that Cx43 and NR1 reduction in hippocampus may be a mechanism for spatial memory impairment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the individuals who helped to make this study possible. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471958).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Khan Z, Yaiw KC, Wilhelmi V, Lam H, Rahbar A, Stragliotto G, Söderberg-Nauclér C. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early proteins promote degradation of connexin 43 and disrupt gap junction communication: implications for a role in gliomagenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:145–154. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:202–213. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogura T, Tanaka J, Kamiya S, Sato H, Ogura H, Hatano M. Human cytomegalovirus persistent infection in a human central nervous system cell line: production of a variant virus with different growth characteristics. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2605–2616. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-12-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagemeier C, Walker S, Caswell R, Kouzarides T, Sinclair J. The human cytomegalovirus 80-kilodalton but not the 72-kilodalton immediate-early protein transactivates heterologous promoters in a TATA box-dependent mechanism and interacts directly with TFIID. J Virol. 1992;66:4452–4456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4452-4456.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortunato EA, Sommer MH, Yoder K, Spector DH. Identification of domains within the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early 86-kilodalton protein and the retinoblastoma protein required for physical and functional interaction with each other. J Virol. 1997;71:8176–8185. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8176-8185.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki K, Murtuza B, Suzuki N, Khan M, Kaneda Y, Yacoub MH. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein IE2-86, but not IE1-72, causes graft coronary arteriopathy in the transplanted rat heart. Circulation. 2002;106(Suppl 1):I158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres L, Tang Q. Immediate-Early (IE) gene regulation of cytomegalovirus: IE1-and pp71-mediated viral strategies against cellular defenses. Virol Sin. 2014;29:343–352. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3532-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu D, Yang L, Xu XY, Zhang GC, Bu XS, Ruan D, Tang JL. Effects of congenital HCMV infection on synaptic plasticity in dentate gyrus (DG) of rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2011;1389:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko YH, Kwon SH, Hwang JY, Kim KI, Seo JY, Nguyen TL, Lee SY, Kim HC, Jang CG. The memory-enhancing effects of liquiritigenin by activation of NMDA receptors and the CREB signaling pathway in mice. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2017 doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2016.284. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. NMDA-receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity: multiple forms and mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:521–527. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90197-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraus M, Smith G, Butters M, Donnell A, Dixon E, Yilong C, Marion D. Effects of the dopaminergic agent and NMDA receptor antagonist amantadine on cognitive function, cerebral glucose metabolism and D2 receptor availability in chronic traumatic brain injury: a study using positron emission tomography (PET) Brain Inj. 2005;19:471–479. doi: 10.1080/02699050400025059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wörsdörfer P, Maxeiner S, Markopoulos C, Kirfel G, Wulf V, Auth T, Urschel S, von Maltzahn J, Willecke K. Connexin expression and functional analysis of gap junctional communication in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:431–439. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanton RJ, McSharry BP, Rickards CR, Wang ECY, Tomasec P, Wilkinson GW. Cytomegalovirus destruction of focal adhesions revealed in a high-throughput Western blot analysis of cellular protein expression. J Virol. 2007;81:7860–7872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02247-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen N, Mo LQ, Hu F, Chen PX, Guo RX, Feng JQ. A novel role of spinal astrocytic connexin 43: mediating morphine antinociceptive tolerance by activation of NMDA receptors and inhibition of glutamate transporter-1 in rats. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20:728–736. doi: 10.1111/cns.12244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu D, Yang L, Bu X, Tang J, Fan X. NMDA receptor subunit and CaMKII changes in rat hippocampus by congenital HCMV infection: a mechanism for learning and memory impairment. Neuroreport. 2017;28:253–258. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeves M, MacAry P, Lehner P, Sissons J, Sinclair J. Latency, chromatin remodeling, and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus in the dendritic cells of healthy carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4140–4145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408994102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Söderberg-Nauclér C. Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? J Intern Med. 2006;259:219–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholz M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J. Inhibition of cytomegalovirus immediate early gene expression: a therapeutic option? Antiviral Res. 2001;49:129–145. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosugi I, Kawasaki H, Tsuchida T, Tsutsui Y. Cytomegalovirus infection inhibits the expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the developing mouse hippocampus and primary neuronal cultures. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0987-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nihei M, Desmond N, McGlothan J, Kuhlmann A, Guilarte T. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit changes are associated with leadinduced deficits of long-term potentiation and spatial learning. Neuroscience. 2000;99:233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen SC, Pelletier DB, Ao P, Boynton AL. Connexin43 reverses the phenotype of transformed cells and alters their expression of cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:681–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldskogius H, Kozlova EN. Central neuronglial and glial-glial interactions following axon injury. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55:1–26. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagy JI, Dudek FE, Rash JE. Update on connexins and gap junctions in neurons and glia in the mammalian nervous system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;47:191–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nie H, Weng HR. Glutamate transporters prevent excessive activation of NMDA receptors and extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the spinal dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2041–2051. doi: 10.1152/jn.91138.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]