Abstract

Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs) are multipotent cells that have self-renewal properties and can differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes, cartilage and extoderm. Bone regeneration and repair are important for the repair of bone injury, skeletal development or continuous remodeling throughout adult life. Thus, investigating the factors influencing osteocyte regeneration from hUCMSCs could be conducive to advancements in skeletal repair and the repair of bone injury. Previous reports have demonstrated that single integrin subunits (αV, β3, α5) and collagen I contribute to the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). However, the functions of the vitronectin receptor αV and β3 in the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs and bone regeneration remain unclear. Run-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) is considered to be an early osteoblastic gene that is upregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. Meanwhile, bone sialoprotein (BSP) and collagen I are the most common early markers of osteoblast differentiation. Herein, we found that the mRNA and protein expression of αV, β3, RUNX2 and collagen I were upregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. Overexpression of αV and β3 in hMSCs increased the levels of RUNX2, BSP, and collagen I, decreased the number of adipocytes and promoted the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. Meanwhile, downregulation of αV and β3 decreased the levels of RUNX2, BSP, and collagen I, increased the number of adipocytes and blocked the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. In conclusion, the integrin subunits αV and β3 can promote the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs and encourage bone formation.

Keywords: Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs), αV, β3, RUNX2, collagen I, osteogenic differentiation

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells that are widely used to repair and regenerate musculoskeletal tissues [1-3]. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs) are a type of MSCs derived from fetal tissues [4]. The hUCMSCs have several advantages over other cell sources in musculoskeletal tissue engineering, as they are easy to isolate and the process is ethically uncomplicated [4-6]. Moreover, hUCMSCs exhibit a low immune rejection response in animal studies [7,8]. Most importantly, as a primitive MSC population, hUCMSCs have higher multipotency compared to MSCs derived from other sources, such as bone marrow or fat [4]. Previous studies have shown that hUCMSCs exert potential key functions in the engineering of bone tissue when cultured in a three-dimensional (3D) scaffold, both in vitro and in vivo [9]. The hUCMSCs are an excellent source of osteocytes for bone injury repair and are important to the discovery of factors influencing osteogenic differentiation.

Vitronectin and collagen I promote osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [10]. A previous study demonstrated that osteogenic stimulation induces the upregulation of single integrin subunits (αV, β3, α5) and the formation of the integrin receptors α5β1 and αVβ3 [11]. The collagen I receptor, α1β1 integrin and the VN receptor, αVβ3 integrin, are key molecules in the main signaling pathway that promotes osteogenesis [10,12]. The vitronectin receptor (αVβ3) is a ubiquitous receptor that interacts with several ligands, such as vitronectin, fibronectin (FN), osteopontin, and metalloproteinase MMP-2 [12,13]. FN is the first extracellular matrix (ECM) that is actively assembled by many cell types upon injury [14]. FN promotes the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs [14,15]. As a consequence, this integrin receptor participates in diverse biologic processes such as cell migration, tumor invasion, bone resorption, angiogenesis, and the immune response [13]. However, the effects of the vitronectin receptors αV and β3 on the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs and bone regeneration have not been elucidated.

Run-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) is considered to be an early osteoblastic gene that is crucial for mesenchymal condensation, osteoblast development, osteoblast maturation and skeletal development [16]. RUNX2 is the master transcription factor of bone formation and plays a vital role in osteogenesis [17]. Adequate RUNX2 expression is important for normal bone development [16,17]. Decreased RUNX2 expression results in abnormal bone development [17]. The mRNA level of RUNX2 is upregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs [6]. Meanwhile, bone sialoprotein (BSP) and collagen I are the most common early markers of osteoblast differentiation [18]. Therefore, we hypothesize that αV and β3 could promote osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration. Herein, we determined the expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 during hUCMSCs (HUXUB-01001) osteogenic differentiation. The expression levels of αV and β3 during adipogenic differentiation were also determined by RT-PCR and WB in HUXUB-01001 cells. Next, the expression of αV and β3 were regulated by a corresponding antibody or plasmid, and the expressions of RUNX2 and collagen I were detected by RT-PCR and WB. The BSP level was evaluated by immunofluorescence staining in cells treated with anti-αV and anti-β3 as well as in cells transfected with plasmids encoding αV and β3. The results showed that αV and β3 promoted the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs and encouraged bone regeneration.

Materials and experiments

Cell culture

Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs) were obtained from Cyagen Biosciences Inc. (Guangzhou, Cat. HUXUB-01001). The hUCMSCs were cultured at 37°C in humid conditions containing 5% CO2 in control medium (HyClone Advance STEM cryopreservation medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin sulfate). For adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs, human adipose-derived stem cell adipogenic differentiation medium (HUXMA-90041) were used in the experiments. The effect of fibronectin (FN) on osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation was determined by adding FN to the control medium and HUXMA-90041 medium. The αV and β3 antibodies were added to the medium to decrease the levels of αV and β3. The αV and β3 plasmids were transfected into the cells to upregulate subunits αV and β3.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated from hUCMSCs cultured for 7 days, 14 days and 21 days on tissue culture plastic plates in the presence of FN, αV and β3 antibody or plasmid in control medium or HUXMA-90041 medium. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol. The mRNA expression of RUNX2, Collagen I, αV and β3 were detected by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan). The primer sequences used in the experiment were as follows: RUNX2 forward primer: 5’-CCTAGGCGC ATTTCAGGTGCTT-3’, RUNX2 reverse primer: 5’-CTGAGGTGACTGGCGGGG TGT-3’; collagen I forward primer: 5’-TGCTTGAATGTGCTGATGACAGGG-3’, collagen I reverse primer: 5’-TCCCCTCACCCTCCCAGTA-3’; αV forward primer: 5’-GTTATTTGGGTTACTCTGTGGCTGTT-3’, αV reverse primer: 5’-GTTTGATGACACTGTTGAAGGTGAAGC-3’; β3 forward primer: 5’-CCATGATCGGAAGGAGTTTGCT-3’, β3 reverse primer: 5’-AAGGTGGATGTG GCCTCTTTATAC-3’; 18 s rRNA forward primer: 5’-CCTGGATACCGCAGCTA GGA-3’, 18 s rRNA reverse primer: 5’-GCGGCGCAATACGAATGCCCC-3’. The mRNA expression of Cofilin 1 was determined by RT-PCR using SYBR Green PC Master Mix (Toyobo, Japan). The thermocycler conditions were as follows: an initial incubation at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 5 min, followed by a PCR program of 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 15 seconds and 72°C for 30 seconds for 40 cycles, with a final step at 72°C for 5 s. Reactions were conducted using the ABI PRISM® 7500 Sequence Detection System. All data were normalized to the expression levels of the control samples. The mRNA expression of genes was calculated using the relative quantification equation (RQ=2-ΔΔCt) [19].

Western blot (WB) experiments

The protein expression levels of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 in hUCMSCs cultured for 7 days, 14 days and 21 days on tissue culture plastic plates in the presence of FN, αV and β3 antibodies or plasmids in control medium or HUXMA-90041 medium were evaluated with western blot (WB) experiments. The protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Keygen Biotech). Protein expression was detected with a RUNX2 monoclonal antibody (ab76956, 1:1000, Abcam, USA), collagen I monoclonal antibody (ab34710, 1:2000, Abcam, USA), αV monoclonal antibody (sc-10719, 1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), β3 monoclonal antibody (sc-6627, 1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), and GAPDH polyclonal antibody (AP0063, 1:10,00, Bioworld) and then visualized using a commercial Immobilon Western HRP Substrate (WBKLS0500, Millipore, USA) under dark conditions.

Oil red O staining for in vitro adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs

Oil red O (Cat. # 0-0625, Sigma) staining for in vitro adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs was performed as previously described [20]. Following adipogenic differentiation, the medium was removed, the cells were washed with 1×PBS, and fixed in 2 ml 4% formaldehyde solution for 30 min. Next, the cells were stained with 1 ml oil red O solution for 30 min and were observed and photographed under a light microscope (OLYMPUS CKX41, U-CTR30-2).

Immunofluorescence staining

The expression of the osteogenic marker bone sialoprotein (BSP) was investigated with immunofluorescence staining [21]. Following osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs (21 days), the cells were preserved with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Non-specific antigens were blocked with 5% BSA. The cells were stained with primary antibodies against human bone sialoprotein (BSP) to examine osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs at 4°C overnight, after which they were washed off with PBS. The cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with PBS. The cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) for 5 min in the dark and finally, washed three times with PBS. The cells were imaged using fluorescence microscopy (Leica, DMI6000B).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 19.0 software. The data are presented as the mean ± SD from three separate experiments. Statistical significance was determined by paired or unpaired Student’s t-test in cases of standardized expression data.

Results

The expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 were was increased during osteogenic differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells

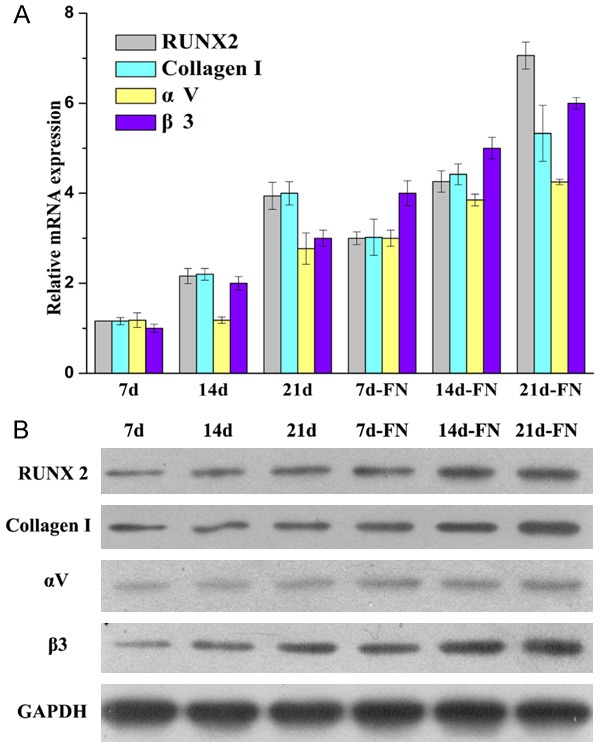

The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 were determined by RT-PCR and WB, respectively, during HUXUB-01001 osteogenic differentiation (Figure 1A and 1B). Thus, the expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 were increased proportionally with the time in culture in the control samples (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and in the FN-treated samples (7 d-FN, 14 d-FN and 21 d-FN). The expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 in the FN-treated group was higher than that of the control group, which was time-dependent. FN can promote the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. Therefore, RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 were upregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs.

Figure 1.

The expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 were determined in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and the FN group (7 d-FN, 14 d-FN and 21 d-FN) during HUXUB-01001 osteogenic differentiation. A. The mRNA expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 was determined by RT-PCR. B. The protein expression of RUNX2, collagen I, αV and β3 was determined by WB.

The expression of αV and β3 was decreased during adipogenic differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells

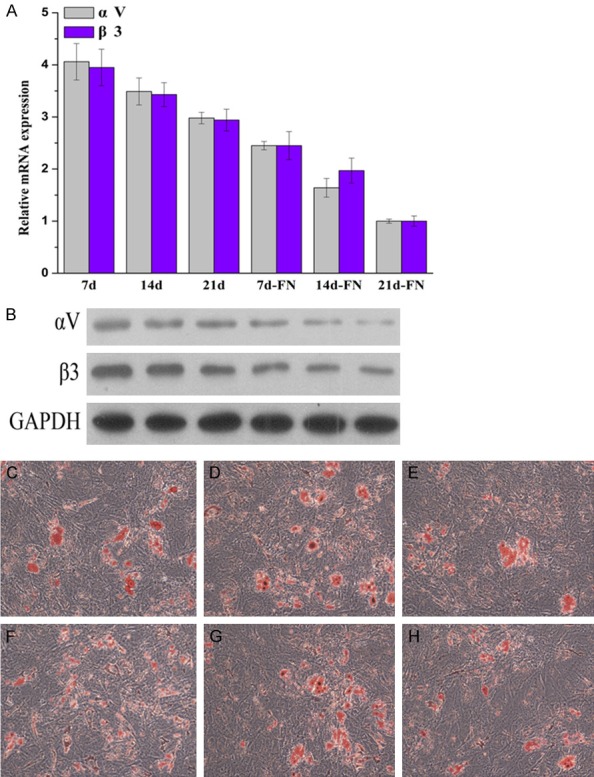

The mRNA and protein expression of αV and β3 were determined by RT-PCR and WB, respectively, during adipogenic differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells (Figure 2A and 2B). The mRNA and protein expression of αV and β3 were decreased in proportion to the time in culture in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and the FN-treated group (7 d-FN, 14 d-FN and 21 d-FN). The expression of αV and β3 in the FN-treated group was lower than that in the control group. FN blocks the adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. The αV and β3 subunits were downregulated during the adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs.

Figure 2.

The expression of αV and β3 was determined in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and the FN group (7 d-FN, 14 d-FN and 21 d-FN) during HUXUB-01001 adipogenic differentiation. A. The mRNA expression of αV and β3 was determined by RT-PCR. B. The protein expression of αV and β3 was determined by WB. C-H. Oil red O staining for investigating the in vitro adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs treated with the αV and β3 antibody or plasmid. C. The control group. D. The anti-αV group. E. The αV plasmid. F. The control group. G. The anti-β3 group. H. The β3 plasmid group.

Oil red O staining was used to investigate the adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs in vitro (Figure 2C-H). Compared to the αV-NC and β3-NC group, the adipogenic cell counts were lower in the αV plasmid and β3 plasmid groups, while the adipogenic cell counts were higher in the anti-αV and anti-β3 group. These results suggested that the upregulation of αV and β3 blocked the adipogenic differentiation, while the downregulation of αV and β3 increased the adipogenic differentiation, indicating that αV and β3 likely play important roles in mediating the differentiation of hUCMSCs.

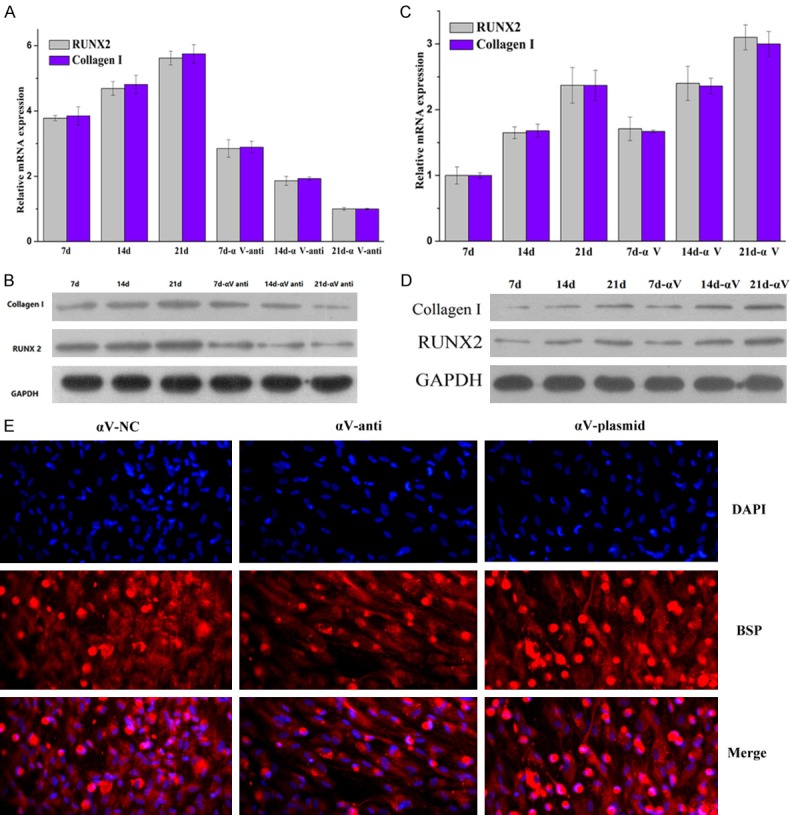

The effect of subunit αV on the expression of RUNX2, collagen I and the differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells

To detect the effect of subunit αV on the differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells, an αV antibody was used to regulate the level of αV. The αV antibody can bind to αV, thereby hindering its function. The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were determined by RT-PCR and WB, respectively, during the osteogenic differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells (Figure 3A and 3B). The expression of RUNX2 and collagen I increased proportionately with the time in culture in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and the αV-anti group (7 d-αV-anti, 14 d-αV-anti and 21 d-αV-anti). The expression of RUNX2 and collagen I in the αV-anti group was higher than that of the control group.

Figure 3.

The αV receptor controls the level of BSP and the expression of RUNX2 and collagen I, as determined by RT-PCR, WB and immunofluorescence staining, respectively. A and C. The mRNA expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were determined by RT-PCR. B and D. The protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were determined by WB. E. The expression of the osteogenic marker, bone sialoprotein (BSP), was investigated with immunofluorescence staining. The cells were treated with an αV antibody or an αV plasmid for 21 days and then stained with DAPI.

To further investigate the function of αV in the differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells, the αV plasmid was transfected into the HUXUB-01001 cells to upregulate the level of αV. The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I decreased proportionately with the time in culture in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and the αV group (7 d-αV, 14 d-αV and 21 d-αV) (Figure 3C and 3D). The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I in the αV group were lower than those of the control group.

The osteogenic marker BSP was investigated by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 3E). BSP was decreased in the αV-anti group compared to the αV-NC group. The BSP was highest in the αV plasmid group. These results suggested that upregulation of the αV subunit promoted the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs.

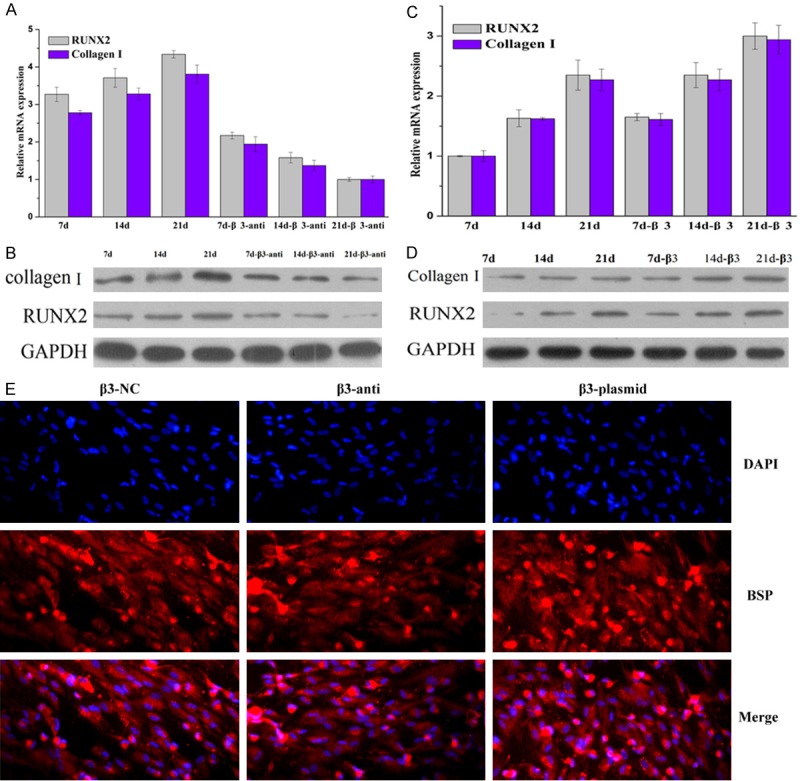

The effect of β3 on the expression of RUNX2, collagen I and the differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells

To determine the effect of β3 on the differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells, a β3 antibody was used to regulate the level of β3. The β3 antibody could bind to the free β3, thereby decreasing its function. The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were determined by RT-PCR and WB, respectively, during the osteogenic differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells (Figure 4A and 4B). The expression of RUNX2 and collagen I increased proportionately with the time in culture in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and the β3-anti group (7 d-β3-anti, 14 d-β3-anti and 21 d-β3-anti). The expression of RUNX2 and collagen I in the β3-anti group was higher than that in the control group.

Figure 4.

The β3 subunit controls the level of BSP and the expression of RUNX2 and collagen I as determined by RT-PCR, WB and immunofluorescence staining, respectively. A and C. The mRNA expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were determined by RT-PCR. B and D. The protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were determined by WB. E. The expression of the osteogenic marker, bone sialoprotein (BSP), was investigated with immunofluorescence staining. The cells were treated with a β3 antibody or a β3 plasmid for 21 days and then stained with DAPI.

To further investigate the function of β3 in the differentiation of HUXUB-01001 cells, the β3 plasmid was transfected into the HUXUB-01001 cells, upregulating the level of β3. The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I were decreased in proportion to the time in culture in the control group (7 d, 14 d and 21 d) and β3 group (7 d-β3, 14 d-β3 and 21 d-β3) (Figure 4C and 4D). The mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 and collagen I in the β3 group were lower than those of the control group.

The expression of the osteogenic marker BSP was visualized by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 4E). The BSP was decreased in the β3-anti group compared to the β3-NC group. The BSP was highest in the β3-plasmid group. These results suggested that the upregulation of β3 promoted the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs.

Discussion

hUCMSCs are multipotent cells with self-renewal properties, which are derived from the human umbilical cord and can differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes, cartilage and extoderm [4,22-24]. Moreover, hUCMSCs can be applied in clinical treatment, such as cell therapy and anti-cancer therapy. These cells can alter immune cell function by inhibiting T-cell, B-cell and natural killer (NK) cell proliferation [25]. Therefore, investigating the regulation governing the differentiation of hUCMSCs and uncovering the specific functions of hUCMSCs in clinical treatment, bone regeneration and immune regulation require further investigation.

The differentiation of hUCMSCs is affected and regulated by many factors (such as TAZ, PPARγ, C/EBPα, RUNX-2) and pathways (Wnt and insulin signaling pathways) [4]. Previous studies have shown that the transcription coactivator TAZ negatively regulates adipogenesis and promotes osteogenesis through the suppression of PPARγ and activation of RUNX-2 [26]. Overexpression of PPARγ suppresses osteogenic differentiation and bone formation. Additionally, many secreted Wnt family proteins promote the differentiation and maintenance of osteoblasts while decreasing the differentiation of adipocytes [26]. Bone regeneration and repair is a part of the repair process in response to injury and skeletal development or in continuous remodeling throughout adult life, which can optimize skeletal repair and restore skeletal function [27,28]. Chemical stimuli, such as dexamethasone, transforming growth factor β3 and insulin, could change the morphology, proliferation and gene expression patterns of hMSCs, and further induce osteogenic differentiation [10]. However, the factors driving the differentiation of hMSCs are not fully elucidated, and the mechanisms underlying the factors controlling the differentiation of hMSCs have not been extensively studied.

Herein, we investigated the effects of the vitronectin receptors αV and β3 on the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. The mRNA and protein expression levels of αV, β3, RUNX2 and collagen I were upregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs, which was consistent with previous reports [18,29]. FN significantly promoted the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSC, while inhibiting the adipogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs, which was consistent with previous studies [14]. The levels of RUNX2, BSP and collagen I, the markers of osteogenic differentiation [29], were evaluated in this paper. The results showed that upregulation of αV and β3 increased the levels of RUNX2, BSP, collagen I, decreased the number of adipocytes, and promoted the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. Meanwhile, downregulation of αV and β3 decreased the levels of RUNX2, BSP, and collagen I, increased the number of adipocytes and blocked the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs. Taken together, the functions of αV and β3 in the differentiation of hUCMSCs are similar to those of FN. The αV and β3 vitronectin receptors can promote osteogenic differentiation as well as bone formation. These results provide valuable insights into the regulation of the osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs and bone formation, which is important for bone injury repair.

RUNX2 is a transcription factor that is known to promote the osteoblast precursor and bone formation and also blocks the adipocyte precursor [30]. The extracellular matrix (ECM), which includes FN, vitronectin, and collagen I, among others, can influence cell behavior by binding to specific integrin cell surface receptors [31,32]. Collagen I or vitronectin can induce the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs [33]. Previous studies have shown that the vitronectin receptor (αVβ3) is a ubiquitous receptor that interacts with several ligands, such as vitronectin and fibronectin (FN) [32].

Conclusion

Herein, we found that αV and β3 could promote osteogenic differentiation as well as bone formation. However, the mechanisms governing the upregulation of αV and β3 and the subsequent increase in RUNX2, collagen I and in osteogenic differentiation of hUCMSCs requires further investigation. Currently, there are no known signaling pathways that regulate the differentiation of hUCMSCs, including the αV and β3 subunits, which require further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Yunnan Provincial Natural and Science Foundation (2014NS174).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Murray IR, Péault B. Q&A: Mesenchymal stem cells - where do they come from and is it important? BMC Biol. 2015;13:99. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0212-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nombela-Arrieta C, Ritz J, Silberstein LE. The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:126–131. doi: 10.1038/nrm3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum AJ, Grande DA, Dines JS. The use of mesenchymal stem cells in tissue engineering: a global assessment. Organogenesis. 2008;4:23–27. doi: 10.4161/org.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding DC, Chang YH, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: a new era for stem cell therapy. Cell Transplantation. 2015;24:339–347. doi: 10.3727/096368915X686841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klontzas ME, Vernardis SI, Heliotis M, Tsiridis E, Mantalaris A. Metabolomics analysis of the osteogenic differentiation of umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells reveals differential sensitivity to osteogenic agents. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26:723–733. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang KX, Xu LL, Rui YF, Huang S, Lin SE, Xiong JH, Li YH, Lee WY, Li G. The effects of secretion factors from umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells on osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Zhao L, Detamore MS. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells in a sandwich approach for osteochondral tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5:712–721. doi: 10.1002/term.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thein-Han W, Xu HH. Collagen-calcium phosphate cement scaffolds seeded with umbilical cord stem cells for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2943–2954. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Song L, Jiang C, Liu Y, George J, Ye H, Cui Z. Electrophysiological properties and synaptic function of mesenchymal stem cells during neurogenic differentiation - a mini-review. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35:323–337. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salasznyk RM, Williams WA, Boskey A, Batorsky A, Plopper GE. Adhesion to vitronectin and collagen I promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2004;2004:24–34. doi: 10.1155/S1110724304306017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Benedetto A, Brunetti G, Posa F, Ballini A, Grassi FR, Colaianni G, Colucci S, Rossi E, Cavalcanti-Adam EA, Lo Muzio L, Grano M, Mori G. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from dental bud: Role of integrins and cadherins. Stem Cell Res. 2015;15:618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Docheva D, Popov C, Mutschler W, Schieker M. Human mesenchymal stem cells in contact with their environment: surface characteristics and the integrin system. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:21–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider JG, Amend SH, Weilbaecher KN. Integrins and bone metastasis: Integrating tumor cell and stromal cell interactions. Bone. 2011;48:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li B, Moshfegh C, Lin Z, Albuschies J, Vogel V. Mesenchymal stem cells exploit extracellular matrix as mechanotransducer. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2425. doi: 10.1038/srep02425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamadyar-Toupkanlou F, Vasheghani-Farahani E, Hanaee-Ahvaz H, Soleimani M, Dodel M, Havasi P, Ardeshirylajimi A, Taherzadeh ES. Osteogenic differentiation of MSCs on fibronectin coated and nHA-modified scaffolds. ASAIO J. 2017;63:684–691. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long F, Ornitz DM. Development of the endochondral skeleton. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a008334. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu TM, Lee EH. Transcriptional regulatory cascades in Runx2-dependent bone development. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013;19:254–263. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang W, Yang S, Shao J, Li YP. Signaling and transcriptional regulation in osteoblast commitment and differentiation. Front Biosci. 2007;12:3068–3092. doi: 10.2741/2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pittenger MF. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohn Yakubovich D, Sheyn D, Bez M, Schary Y, Yalon E, Sirhan A, Amira M, Yaya A, De Mel S, Da X, Ben-David S, Tawackoli W, Ley EJ, Gazit D, Gazit Z, Pelled G. Systemic administration of mesenchymal stem cells combined with parathyroid hormone therapy synergistically regenerates multiple rib fractures. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:51. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0502-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaiswal RK, Jaiswal N, Bruder SP, Mbalaviele G, Marshak DR, Pittenger MF. Adult human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to the osteogenic or adipogenic lineage is regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9645–9652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latifpour M, Shakiba Y, Amidi F, Mazaheri Z, Sobhani A. Differentiation of human umbilical cord matrix-derived mesenchymal stem cells into germ-like cells. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2014;6:218–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.English K, French A, Wood KJ. Mesenchymal stromal cells: facilitators of successful transplantation? Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotter EJ, Mallon PW, Doran PP. Is PPARγ a prospective player in HIV-1-associated bone disease? PPAR Res. 2009;2009:421376. doi: 10.1155/2009/421376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimitriou R, Jones E, McGonagle D, Giannoudis PV. Bone regeneration: current concepts and future directions. BMC Med. 2011;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, Longaker MT. Bone regeneration and repair. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;5:122–128. doi: 10.2174/157488810791268618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu CY, Ji M, Wang XC. Effects of acidosis on the osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:23182–23189. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonason JH, Xiao G, Zhang M, Xing L, Chen D. Post-translational regulation of Runx2 in bone and cartilage. J Dent Res. 2009;88:693–703. doi: 10.1177/0022034509341629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4195–4200. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeltz C, Orgel J, Gullberg D. Molecular composition and function of integrin-based collagen glues--Introducing COLINBRIs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2533–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salasznyk RM, Klees RF, Hughlock MK, Plopper GE. ERK signaling pathways regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on collagen I and vitronectin. Cell Commun Adhes. 2004;11:137–153. doi: 10.1080/15419060500242836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]