Abstract

Objective: To assess the value of immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Methods: We selected 55 cases of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma confirmed by histopathology and 15 cases of reactive lymph node hyperplasia. Using the IdentiClone gene rearrangement detection kit, BIOMED-2 primer system, and GeneScanning analysis, we tested for immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements. Results: Among all 55 angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma cases, 1 (2%) displayed the first type of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, which has an intact lymphoid follicle structure. Five cases (9%) displayed the second type, which has an intact segmental lymphatic follicular structure. Forty-nine cases (89%) displayed the third type, which is characterized by a complete obliteration of the lymphatic follicular structure. Fifty-two cases (95%) had tumor cells that were positive for CD3, 50 cases (91%) were positive for CD4, 33 cases (60%) were positive for Bcl-6, 20 cases (36%) were positive for CD10, 44 cases (80%) were positive for CXCL13 to different degrees, and 53 cases (96%) showed a strong positive expression of CD21. Ki67 expression intensity was 30-80% in tumor T cells. Clonal gene rearrangements were identified in 48 of the 55 angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma cases (87%), of which 30 (55%) displayed IG gene rearrangements, including IGHA (7 cases; 13%), IGHB (6 cases; 11%), IGHC (2 cases; 4%), IGKA (22 cases; 40%), IGKB (6 cases; 11%), and IGL (20 cases; 36%). TCR gene rearrangements were observed in 32 cases (58%), including TCRBA (6 cases; 11%), TCRBB (5 cases; 9%), TCRBC (10 cases; 18%), TCRD (7 cases; 13%), TCRGA (22 cases; 40%), and TCRGB (16 cases; 29%). IG and TCR gene rearrangements were concurrently observed in 14 cases (25%). Immunoglobulin or TCR clonal gene rearrangements were not detected in the 15 cases of reactive hyperplasia. Conclusions: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas may be positive for immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor clone gene rearrangements or may express double rearrangements. The assessment of clonal gene rearrangements is valuable for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

Keywords: Immunoglobulin, T cell receptor, gene rearrangements, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

Introduction

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a rare and aggressive subtype of lymphoma but accounts for a major subset of peripheral T-cell lymphomas. AITL is characterized clinically by the sudden onset of its constitutional symptoms, which include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and in particular, hemolytic anemia [1-5]. AITL causes a unique stromal reaction, and its pathologic characteristics include polymorphic T-cell infiltration, high venous endothelial proliferation, follicular dendritic-cell proliferation, polyclonal B-cell infiltration, and inflammatory cell infiltration. AITL is often associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. The tumor cells originate from the auxiliary T lymphocytes in the germinal center.

The typical histologic features of AITL include the following: (1) The lymph nodes contain polymorphic small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with a transparent cytoplasm, round or ovoid nucleus, and small nucleoli. (2) There are large, scattered immunoblast-like cells, which have one or two nucleoli and a basophilic cytoplasm; (3) There is obvious hyperplasia of the high endothelial branched vein, and the endothelial cells are swollen. The blood vessel cells with a hyaline cytoplasm are often surrounded by atypical lymphocytes. (4) There is a proliferation of follicular dendritic cells with a “branch” or “windblown” shape. (5) The background of inflammatory cells includes small lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and histocytes. (6) The peripheral sinus of the lymph nodes is often present, and the peripheral fatty tissue is infiltrated by the tumor tissue.

AITL can be categorized into three types. Type 1 is rare, and its early pathologic changes consist of an intact lymphoid follicle structure and T area expansion only. Type 2 is characterized by an intact segmental lymphatic follicular structure. Type 3 is characterized by a complete obliteration of the lymphatic follicular structure [6]. The first two types are frequently observed in T-area reactive hyperplasia. The third type is relatively common and often needs to be distinguished from peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and T-cell-rich large B cell lymphoma.

We used the BIOMED-2 primer design system, the IdentiClone gene rearrangement detection kit, and the GeneScanning method to assess clonality and detect immunoglobulin (IG) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements in 55 cases of AITL and 15 cases of reactive hyperplasia.

Materials and methods

Case information

A total of 55 excised AITL samples collected by the pathology department at Xiangya Hospital from October 2012 to October 2016 were used for the study. Of the 55 cases, 39 were from males, and 16 were from females. The age of the patients from whom the samples were obtained ranged from 36 to 78 years (mean age, 61). The control group was composed of 15 cases of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.

Reagents

The following antibodies were used: CD3, CD4, CD10, CD21, CD20, PAX-5, CXCL13, Ki67, and Bcl-6. All antibodies were purchased from the Fuzhou Maixin company (Fuzhou, China). The IdentiClone™ B-Cell Clonality Assay Kit was purchased from InVivoScribe Technologies, and the 20 bp DNA Ladder and 10x loading buffer were purchased from Takara. GelRed dye was purchased from BioTium, AmpliTaq Gold Taq from ABI, and DNA FFPE tissue kit from Xiamen Aide Biomedicine Limited company.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) experiments

The detailed procedure was given previously [7-9]. All specimens were fixed using 10% neutral formalin. Dehydration, paraffin embedding, serial sectioning, and conventional hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and IHC staining were performed. IHC staining was performed using the streptavidin-peroxidase (SP) method. We used 4-μm thick paraffin sections with a conventional dewaxing method, and distilled water was used for washing. Microwave antigen retrieval was performed. The sections were placed in 0.01 mL citric acid antigen retrieval liquid, processed using microwave heat for two 5-min cycles, washed in distilled water, and placed in PBS. Next the sections were incubated in 3% methanol H2O2 and washed in distilled water for 10 min. The samples were incubated at 4°C overnight and then rinsed with PBS 3 times for 5 min. Following incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the samples were rinsed in PBS 3 times for 5 min. Then, DAB staining, hematoxylin staining, and conventional mounting were performed.

DNA extraction

Ten paraffin sections of 8-μm thickness were transferred to a 1.5 ml sterile centrifuge tube, and 1 ml xylene was added. The tube was vibrated slightly and maintained in a 56°C water bath for 10 minutes. After centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 3 minutes, the xylene was discarded, and the dewaxing procedure was repeated twice. Then, 1 ml absolute ethyl alcohol was added and mixed until uniform, the solution was centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 3 minutes, the supernatant was discarded, and the procedure was repeated 3 times. Next, the centrifuge tube was placed in a 56°C incubator to dry. After drying, the genomic DNA was extracted using a kit, and an ultraviolet spectrophotometer was used to determine the concentration and purity of the DNA. The ideal OD260/OD280 value should be between 1.8 and 2.0. If the purity was inadequate or the concentration was not sufficient, re-extraction was carried out.

Primer design

The BIOMED-2 primer system was employed for the analysis of IG and TCR gene clonal rearrangements [10]. The size range of the bands specific for the different IG primer groups were as follows: IGHA, 310-360 bp; IGHB, 250-295 bp; IGHC, 100-170bp; IGKA, 120-300 bp; 190-210 bp, 260-300 bp, IGKB 210-250 bp, 270-300bp, 350-390 bp, IGL 135-170 bp. The size range of the bands specific for the different TCR primer groups were as follows: TCRBA, 240-285 bp; TCRBB, 240-285 bp; TCRBC, 170-210 bp, 285-325 bp; TCRD, 120-280 bp; TCRGA, 145-255 bp; TCRGB. 80-220 bp. There were also 5 pairs of BIOMED-2 internal control primers. To analyze the integrity of the extracted DNA, the fragments amplified with these primers should be 100, 200, 300, 400 and 600 bp, respectively. The β-actin housekeeping gene was used as an internal control (Table 1).

Table 1.

The BIOMED-2 standardized gene rearrangement primer system

| Primers tube | Primer pairs | Product fragment (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| IGH-A | VH1-FR1 + VH2-FR1 + VH3-FR1 + VH4-FR1 + VH5-FR1 + VH6-FR1 + JH consensus | 310~360 |

| IGH-B | VH1-FR2 + VH2-FR2 + VH3-FR2 + VH4-FR2 + VH5-FR2 + VH6-FR2 + VH7-FR2 + JH consensus | 250~295 |

| IGH-C | VH1-FR3 + VH2-FR3 + VH3-FR3 + VH4-FR3 + VH5-FR3 + VH6-FR3 + VH7-FR3 + JH consensus | 100~170 |

| IGK-A | Vκ1f/6 + Vκ2f + Vκ3f + Vκ4f + Vκ5f + Vκ7f + Jκ1-4 + Jκ5 | 120~160 + 190~210 + 260~300 |

| IGK-B | Vκ1f/6 + Vκ2f + Vκ3f + Vκ4f + Vκ5f + Vκ7f + INTR + κde | 210~250 + 270~300 + 350~390 |

| IGL | Vλ1/2 + Vλ3 + Jλ1/2/3 | 135~170 |

| TCRBA | 23Vβ + 9Jβ (Jβ1.1-1.6 + Jβ2.2 + Jβ2.6 + Jβ2.7) | 260 |

| TCRBB | 23Vβ + 4Jβ (Jβ2.1-2.5) | 260 |

| TCRBC | Dβ1 + Dβ2 + 13Jβ | 300, 190 |

| TCRGA | Jγ1.1/1.2 + Vγ1f + Jγ1.3/2.3 + Vγ10 | 145-255 |

| TCRGB | Jγ1.1/1.2 + Vγ11 + Vγ9 + Jγ1.3/2.3 | 80-140, 160-220 |

| TCRD | Vδ1-Jδ1, Vδ2-Jδ1, Vδ2-Jδ3, Vδ3-Jδ1, Vδ6-Jδ2, Dδ2-Jδ1 | 120-280 |

Preparation of PCR system and PCR amplification

A specimen control size ladder mix in the IdentiClone™ B-Cell Clonality Assays Kit (purchased from InVivoScribe Technologies, www.invivo-scribe.com) was employed to verify the quality of the extracted DNA. If the DNA quality was sufficient, the clonal gene analysis system was prepared. The quantity of mix and enzyme required by the PCR system was calculated using the number of reactions for IgHA, IgHB, IgHC, IgKA, IgKB, and IgL. The total volume of each amplification reaction was 25 μl, which included 22.5 μL of pre-mixed solution, 0.13 μl of AmpliTaq Gold Taq, 2.0 μl of template, and ddH2O to reach 25 μl. The PCR reaction procedure was as follows: 95°C for 7 minutes; 95°C for 45 seconds, 60°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 90 seconds for 34 cycles; 72°C for 10 minutes; and hold at 15°C [11,12].

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis

The PCR products were loaded into the PCR instrument and denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes. They were then moved to the ice bath and incubated for 60 minutes for random renaturation and heteroduplex formation. Then, 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out at 120 V for 1 hour to analyze the heteroduplex products. A 20 bp DNA ladder was used as the molecular standard, and 1x TBE was used as the electrophoretic buffer solution. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained using GelRed for 5 minutes, rinsed for 5 minutes, and then analyzed under a UV gel imaging analyzer.

Data accessibility

The accession numbers or DOIs of any data related to this paper were available in a public database or repository.

Results

Histologic features

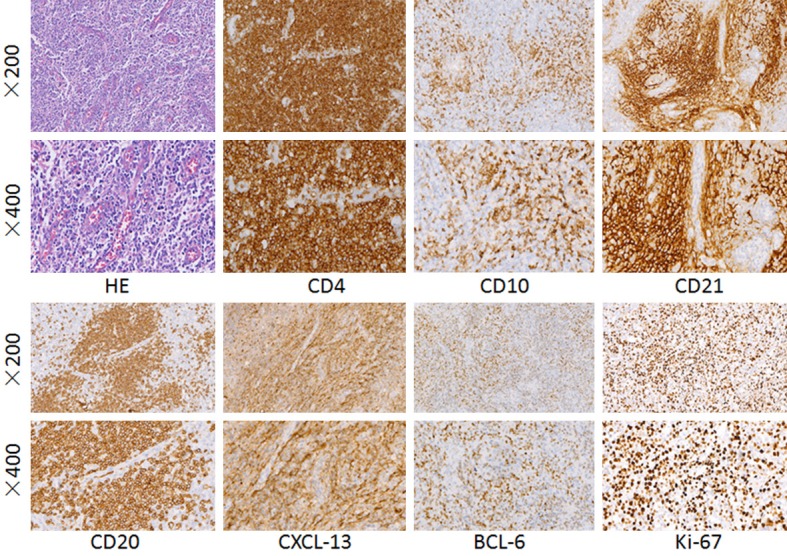

Among the 55 AITL cases, 1 (2%) displayed the first type of AITL, which has an intact lymphoid follicle structure. Five cases (9%) displayed the second type, characterized by an intact segmental lymphatic follicular structure. Forty-nine cases (89%) displayed the third type, characterized by a complete obliteration of the lymphatic follicular structure. The common histologic features of AITL include the following: there is obvious hyperplasia of the high endothelial branched vein, and the endothelial cells are swollen; the blood vessel cells with a hyaline cytoplasm are often surrounded by atypical small to medium lymphocytes; there are large, scattered immunoblast-like cells with one or two nucleoli and a basophilic cytoplasm; and the background of inflammatory cells includes small lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and histocytes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. The hyperplasia of the high endothelial branched vein is obvious, and the endothelial cells are swollen. CD4, CD10, CD21, CD20, CXCL13 immunohistochemical staining were positive in the cytomembrane. Bcl-6, Ki-67 immunohistochemical staining were positive in the nucleus.

Immunohistochemical results

A positive expression was defined by the presence of a particular marker in more than 10% of cells. The cytomembrane was positive for CD3, CD4, CD10, CD21, and CD20. The cytoplasm was positive for CXCL13. The nucleus was positive for Bcl-6, Ki-67 (Figure 1), and PAX-5.

Fifty-two cases (95%) had tumor cells that were positive for CD3, 50 (91%) were positive for CD4, and 33 (60%) were positive for Bcl-6. In small to medium cells, the proportion of positive cells was 20-60%, corresponding to the expression of CD3 and CD4. Twenty cases (36%) had tumor cells that were positive for CD10, from focally to partially positive (approximately 15-50%), consistent with the other T-cell markers described above. Forty-four cases (80%) were positive for CXCL13 to different degrees, and the proportion of positive cells was 30-80%, similar to other T-cell markers. Fifty-three cases (96%) showed a strong positive expression of CD21 and hyperplasia of the follicular dendritic network. Cases positive for CD34 expression showed vascular proliferation and endothelial cell swelling. The Ki67 expression intensity was 30-80% in tumor T cells (Table 2).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical findings in AITL cases (n=55)

| Antibody | Positive cases | Positive rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CD3 | 52 | 95 |

| CD4 | 50 | 91 |

| CD21 | 53 | 96 |

| CD10 | 20 | 36 |

| CXCL13 | 44 | 80 |

| Bcl-6 | 33 | 60 |

Analysis of IG and TCR clonal gene rearrangements

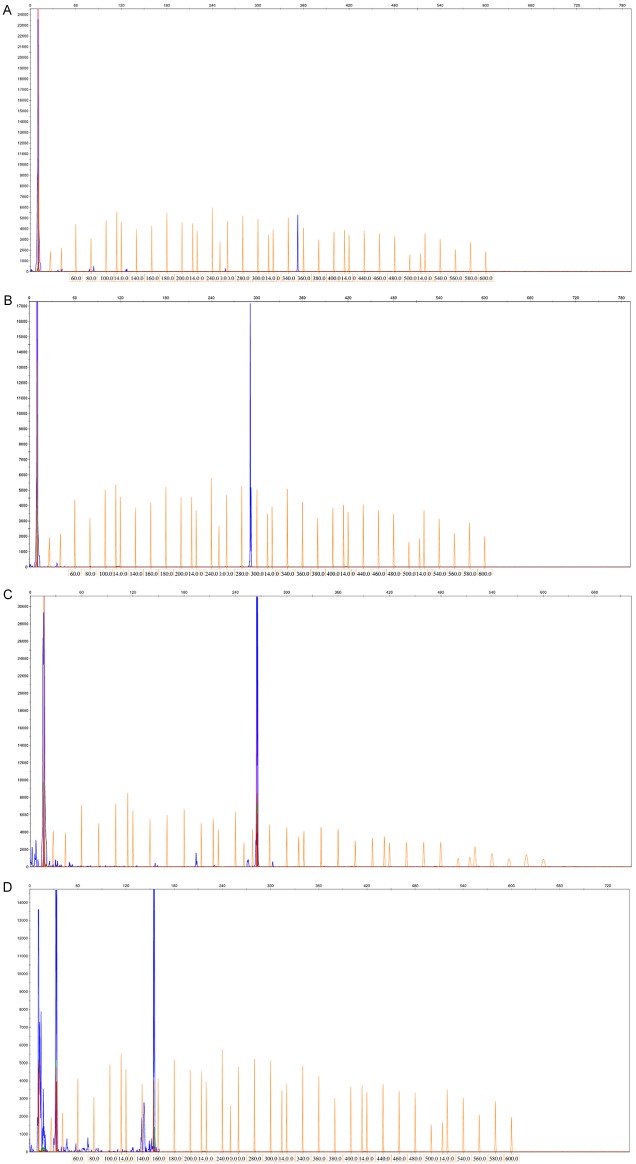

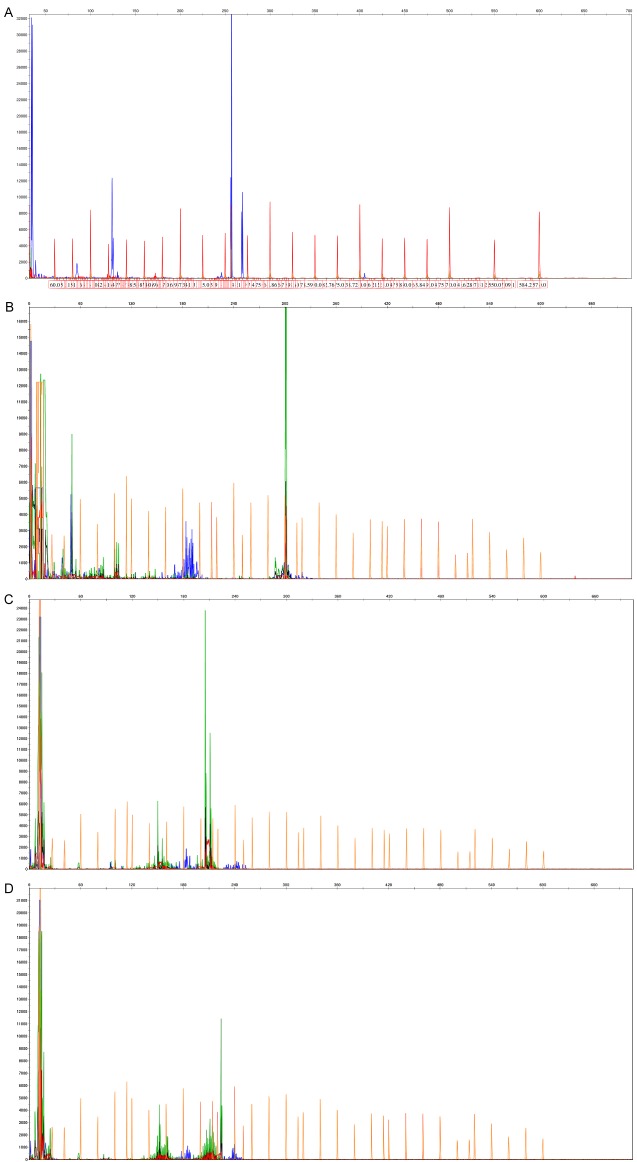

Clonal gene rearrangements were identified in 48 of the 55 AITL cases (87%), of which 30 (55%) displayed IG gene rearrangements, including IGHA (7 cases; 13%), IGHB (6 cases; 11%), IGHC (2 cases; 4%), IGKA (22 cases; 40%), IGKB (6 cases; 11%), IGL (20 cases; 36%) (Figure 2). TCR gene rearrangements were observed in 32 patients (58%), including TCRBA (6 cases; 11%), TCRBB (5 cases; 9%), TCRBC (10 cases; 18%), TCRD (7 cases; 13%), TCRGA (22 cases; 40%), TCRGB (16 cases; 29%) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Immunoglobulin (IG) clonal gene rearrangements were identified in the 55 AITL cases by the BIOMED-2 primer system. A. IGHA gene rearrangements were detected; B. IGHB gene rearrangements were detected; C. IGKA gene rearrangements were detected; D. IGL gene rearrangements were detected.

Figure 3.

T cell receptor (TCR) clonal gene rearrangements were identified in the 55 AITL cases by the BIOMED-2 primer system. A. TCRBB gene rearrangements were detected. B. TCRBC gene rearrangements were detected. C. TCRGA gene rearrangements were detected. D. TCRGB gene rearrangements were detected.

IG and TCR gene rearrangements were concurrently observed in 14 patients (25%) (Table 3). Immunoglobulin or TCR clonal gene rearrangements were not detected in the 15 cases of reactive hyperplasia.

Table 3.

Results of IG and TCR clonal gene rearrangement analysis in AITL (n=55)

| Reaction tube | Positive cases | Positive rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| IGHA | 7 | 13 |

| IGHB | 6 | 11 |

| IGHC | 2 | 4 |

| IGKA | 22 | 40 |

| IGKB | 6 | 11 |

| IGL | 20 | 36 |

| IG | 30 | 55 |

| TCRBA | 6 | 11 |

| TCRBB | 5 | 9 |

| TCRBC | 10 | 18 |

| TCRD | 7 | 13 |

| TCRGA | 22 | 40 |

| TCRGB | 16 | 29 |

| TCR | 32 | 58 |

| IG/TCR | 48 | 87 |

| IG+TCR | 14 | 25 |

Discussion

AITL is a rare primary peripheral T-cell lymphoma of the lymph node that accounts for 1-2% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and approximately 15% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas [13-15]. The patients in our study were mostly middle-aged and elderly, and the percent of men and women was similar. AITL patients generally have a superficial lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, and the bone marrow is often involved [16]. The disease is always in an advanced stage when it is discovered, and there are systemic symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, night sweats, skin rashes, itching, edema, pleural effusion, arthritis, and others [17-27]. The patients often exhibit high levels of polyclonal immunoglobulins, circulating immune complexes, cold agglutinin hemolytic anemia, rheumatoid factor, and anti-smooth muscle antibodies [28,29].

The current study suggested that AITL was a tumor derived from follicular helper T cells [30-35]. It expresses CD3, CD4, CD43, and CD45RO, as well as the follicular helper T-cell markers [5,36]. CD10 and Bcl-6 are reliable markers of B-cell lymphoma in the germinal center. Studies have shown that most of the AITL tumor T cells express abnormal levels of CD10 and Bcl-6 [15,37,38]. In this study, the positive expression rate of CD10 was 36% and that of Bcl-6 was approximately 60%, which are consistent with the rates reported in the literature [39,40]. CXCL13 is a newly discovered marker specific for follicular dendritic cells [41]. The positive expression rate of CXCL13 in this group was 80%, which was higher than the expression of CD10 and Bcl-6. There was a greater number of CXCL13-positive than CD10-positive cells. CD21 is a specific marker for the follicular dendritic network. The CD21 positive expression rate was 96% in this group, which is consistent with the literature. In addition, some large cells scattered among the tumor T cells expressed B-cell markers, such as CD20, PAX-5. In conclusion, the high expression of CXCL13, CD10, and Bcl-6, combined with the positive expression of CD21 and CD35 in the follicular dendritic network, the swelling of vascular endothelial cells, and the scattered distribution of CD20- and PAX-5-positive tumor cells, can be used for the diagnosis of AITL [42]. In spite of these markers, the diagnosis of AITL is nonspecific and difficult. Thus, the IG and TCR clonal gene rearrangements are novel markers for the diagnosis of AITL.

Gene rearrangement is a normal physiological process that occurs during B- and T-lymphocyte maturation. In the embryonic state, the B and T lymphocyte IG and TCR genes are composed of a variable region (V), diverse region (D), joining region (J), and constant region (C). These regions are nonconsecutive on the chromosome and are separated by insertion sequences of different lengths. After a certain stage of lymphocyte development, these regions realign to assemble into a structural gene, i.e., they undergo gene rearrangements, in a process that is catalyzed by a recombinase [43,44]. Malignant lymphoma is a monoclonal hyperplasia, and all clones theoretically represent clonal gene rearrangements. In contrast, hyperplasia of normal and reactive lymphoid tissues involves polyclonal gene rearrangements.

In 2003, 47 organizations from seven countries in Europe developed the BIOMED-2 multiplex PCR system, which contains 107 primers divided into 18 multiplex PCR tubes [45]. At present in Europe, the United States, and other countries, the IG and/or TCR clonal gene rearrangements are routinely screened for the diagnosis of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The sensitivity of the classic two-primer-pair method is relatively low, and the detection rate is only 30%. The detection rate of the multiple-primer method is 70-100% [46-48]. The detection rates of the IG and TCR gene rearrangements in AITL have differed among studies. Tan et al. used the IGH and TCRγ two-primer method to detect the gene rearrangement in 58 cases of AITL; 78% of cases were positive for TCRγ T-cell clones, and 34% were positive for IGH B-cell clones [49]. Aung et al. [50] used Southern blotting to analyze the presence of TCR-C-beta1 and IGH-JH gene rearrangements in a 70-year-old male with AITL. Ren et al. analyzed the IGH and TCRγ gene rearrangements in 15 cases of AITL using the two-primer-pair method and found that 6/15 (40%) had the TCRγ rearrangement, and 7/15 (46.7%) had the IGH rearrangement [51,52]. In this study, the BIOMED-2 system was employed to analyze the clonal gene rearrangements of IG and TCR in 55 samples of paraffin-embedded AITL tissue. IGH, IGK, IGL and TCRB, TCRD, TCRG multiple primers were used to detect the gene rearrangements in 55 cases of AITL. The results showed that 87% [48] of the cases had clonal gene rearrangements, of which 55% (30 cases) had IG gene rearrangements, 58% (32 cases) had TCR gene rearrangements, and 27% (15 cases) had IG and TCR gene double rearrangements. Compared with the two-primer-pair method, the detection rate of clonal gene rearrangements was significantly improved by using the multiple-primer method.

It has been reported that the IGH gene rearrangement in AITL is related to the CD20- and PAX-5-positive immunoblasts that are scattered among the tumor cells. The CD20- and PAX-5-positive immunoblasts were previously isolated by microdissection and then analyzed for gene rearrangement. The results showed that the isolated CD20- and PAX-5-positive immunoblasts showed only the IG gene rearrangement, while the rest of the AITL tissue showed only the TCR gene rearrangement. The present study showed that 55% of AITL cases had the IG clonal gene rearrangement, which is consistent with the literature and demonstrates that the IG clonal gene rearrangement can be found in AITL [53].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the laboratory members for their critical discussion of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China [2015CB553903 (Y.T.)]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81271763 (S.L.), 81372427 (Y.T.), and the National Nature Foundation of China [81772927 (D.X.)].

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Lunning MA, Vose JM. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: the many-faced lymphoma. Blood. 2017;129:1095–1102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higashiguchi M, Sakai K, Kobayashi T, Doi T, Koyama T, Hoshi M, Taniguchi H, Murakami M, Ikeda K, Kurokawa E, Nakamichi I. A case of angioimmunoblastic t-cell lymphoma merged with colorectal cancer that we were able to resect after a chemotherapy response. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2016;43:1620–1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou Y, Rosenblum MK, Dogan A, Jungbluth AA, Chiu A. Cerebellar EBV-associated diffuse large B cell lymphoma following angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. J Hematop. 2015;8:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s12308-015-0241-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang M, Bennani NN, Feldman AL. Lymphoma classification update: T-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphomas, and histiocytic/dendritic cell neoplasms. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10:239–249. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2017.1281122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao X, Huang W, Li W, Xie J, Zheng Y, Zhou X. Clinicopathologic analysis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg-like cells. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zh. 2015;44:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dogan A, Attygalle AD, Kyriakou C. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:681–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao D, Shi Y, Fu C, Jia J, Pan Y, Jiang Y, Chen L, Liu S, Zhou W, Zhou J, Tao Y. Decrease of TET2 expression and increase of 5-hmC levels in myeloid sarcomas. Leuk Res. 2016;42:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao D, Huang J, Pan Y, Li H, Fu C, Mao C, Cheng Y, Shi Y, Chen L, Jiang Y, Yang R, Liu Y, Zhou J, Cao Y, Liu S, Tao Y. Chromatin remodeling factor LSH is upregulated by the LRP6-GSK3beta-E2F1 axis linking reversely with survival in gliomas. Theranostics. 2017;7:132–43. doi: 10.7150/thno.17032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao D, Huang J, Pan Y, Li H, Fu C, Mao C, Cheng Y, Shi Y, Chen L, Jiang Y, Yang R, Liu Y, Zhou J, Cao Y, Liu S, Tao Y. Opposed expression of IKKalpha: loss in keratinizing carcinomas and gain in non-keratinizing carcinomas. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25499–25505. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, Evans PA, Hummel M, Lavender FL, Delabesse E, Davi F, Schuuring E, García-Sanz R, van Krieken JH, Droese J, González D, Bastard C, White HE, Spaargaren M, González M, Parreira A, Smith JL, Morgan GJ, Kneba M, Macintyre EA. DesIGn and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langerak AW, Groenen PJ, Bruggemann M, Beldjord K, Bellan C, Bonello L, Boone E, Carter GI, Catherwood M, Davi F, Delfau-Larue MH, Diss T, Evans PA, Gameiro P, Garcia Sanz R, Gonzalez D, Grand D, Håkansson A, Hummel M, Liu H, Lombardia L, Macintyre EA, Milner BJ, Montes-Moreno S, Schuuring E, Spaargaren M, Hodges E, van Dongen JJ. EuroClonality/BIOMED-2 guidelines for interpretation and reporting of IG/TCR clonality testing in suspected Lymphop-roliferations. Leukemia. 2012;26:2159–2171. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langerak AW, Molina TJ, Lavender FL, Pearson D, Flohr T, Sambade C, Schuuring E, Al Saati T, van Dongen JJ, van Krieken JH. Poly-merase chain reaction-based clonality testing in tissue samples with reactive lymphoproliferations: usefulness and pitfalls. A report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2007;21:222–229. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang SS, Chen SW, Chang ST, Kuo YT. Lymphoma in taiwan: review of 1347 neoplasms from a single institution according to the 2016 revision of the world health organization classification. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;18:30394–30401. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monabati A, Safaei A, Noori S, Mokhtari M, Vahedi A. Subtype distribution of lymphomas in south of Iran, analysis of 1085 cases based on world health organization classification. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:613–618. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mlika M, Helal I, Laabidi S, Braham E, El Mezni F. Is CD10 antibody useful in the diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma? J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2015;36:510–516. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2014.1001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kameoka Y, Takahashi N, Itou S, Kume M, Noji H, Kato Y, Ichikawa Y, Sasaki O, Motegi M, Ishiguro A, Tagawa H, Ishizawa K, Ishida Y, Ichinohasama R, Harigae H, Sawada K. Analysis of clinical characteristics and prognostic factors for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2015;101:536–542. doi: 10.1007/s12185-015-1763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yachoui R, Farooq N, Amos JV, Shaw GR. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Med Res. 2016;14:159–162. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Lee HY, Koh HY, Busmanis I, Lee YS. Cutaneous presentation of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a harbinger of poor prognosis? Skinmed. 2016;14:469–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min MS, Yao J, Kim SJ. Development of a reticular rash in a febrile woman: an unusual cutaneous presentation of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito K, Okiyama N, Shibao K, Maruyama H, Fujimoto M. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma mimicking dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:837–839. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maher NG, Chiang YZ, Badoux X, Vonthethoff LW, Murrell DF. Saggy skin as a presenting sign of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:386–389. doi: 10.1111/ced.12773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBlanc RE, Lefterova MI, Suarez CJ, Tavallaee M, Kim YH, Schrijver I, Kim J, Gratzinger D. Lymph node involvement by mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome mimickingangioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1382–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He J, Liang H. Skin lesions and neutrophilic leukemoid reaction in a patient with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:483–488. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botros N, Cerroni L, Shawwa A, Green PJ, Greer W, Pasternak S, Walsh NM. Cutaneous manifestations of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinical and pathological characteristics. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:274–283. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ocampo-Garza J, Herz-Ruelas ME, González-Lopez EE, Mendoza-Oviedo EE, Garza-Chapa JI, Ocampo-Garza SS, Vázquez-Herrera NE, Miranda-Maldonado I, Ocampo-Candiani J. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a diagnostic challenge. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:291–295. doi: 10.1159/000370302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan X, Chen F, Bi D, Zhao X, He Q, Li Q. Clinicopathologic features and diagnosis of 18 patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2009;34:523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang XC, Li XL, Huang RX, Jin XS. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors in 73 patients with peripheral T cell lymphoma. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2008;33:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma H, Abdul-Hay M. T-cell lymphomas, a challenging disease: types, treatments, and future. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22:18–51. doi: 10.1007/s10147-016-1045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaffenberger B, Haverkos B, Tyler K, Wong HK, Porcu P, Gru AA. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma-like presentations of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a T-cell lymphoma masquerading as a b-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:604–613. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magro CM, Crowson AN, Morrison C, Merati K, Porcu P, Wright ED. CD8+ lymphomatoid papulosis and its differential diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:490–501. doi: 10.1309/NNV4-L5G5-A0KF-1T06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunleavy K, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: pathological insIGhts and clinical implications. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:348–353. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328186ffbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y, Attygalle AD, Chuang SS, Diss T, Ye H, Liu H, Hamoudi RA, Munson P, Bacon CM, Dogan A, Du MQ. Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma: histological progression associates with EBV and HHV6B viral load. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abruzzo LV, Schmidt K, Weiss LM, Jaffe ES, Medeiros LJ, Sander CA, Raffeld M. B-cell lymphoma after angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphadenopathy: a case with olIGo-clonal gene rearrangements associated with Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 1993;82:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lachenal F, Berger F, Ghesquières H, Biron P, Hot A, Callet-Bauchu E, Chassagne C, Coiffier B, Durieu I, Rousset H, Salles G. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma clinical and laboratory features at diagnosis in 77 patients. Medicine. 2007;86:282–292. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181573059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan CM, Vergilio JA, Zhao XF, Smith TK, Harris NL, Bagg A. CD10 and Bcl-6 expression in the diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: Utility of detecting CD10+T cells by flow eytometry. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz SJ, Cotta CV. Follicular helper T-cell lymphoma: a B-cell-rich variant of T-cell lymphoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loghavi S, Wang SA, Medeiros LJ, Jorgensen JL, Li X, Xu-Monette ZY, Miranda RN, Young KH. Immunophenotypic and diagnostic characterization of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma by advanced flow cytometric technology. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2804–2812. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2016.1170827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adachi Y, Hino T, Ohsawa M, Ueki K, Murao T, Li M, Cui Y, Okigaki M, Ito M, Ikehara S. A case of CD10-negative angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma with leukemic change and increased plasma cells mimicking plasma cell leukemia: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:1555–1560. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishizawa S, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Hattori K, Muto H, Nguyen T, Izutsu K, Yoshida K, Ogawa S, Nakamura N, Chiba S. BCL6 locus is hypermethylated in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2017;105:465–469. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2159-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao ZJ, Surowiecka M, Linden MA, Singleton TP. Abnormal immunophenotype of the T-cell-receptor beta Chain in follicular-helper T cells ofangioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2015;88:190–193. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtani H, Komeno T, Agatsuma Y, Kobayashi M, Noguchi M, Nakamura N. Follicular dendritic cell meshwork in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is characterized by accumulation of CXCL13 (+) cells. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2015;55:61–69. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu C, Li N, Li M, Xue X, Gao Z. Clinicopathological analysis of 64 case of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2014;35:24–28. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humme D, Lukowsky A, Gierisch M, Haider A, Vandersee S, Assaf C, Sterry W, Möbs M, Beyer M. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement analysis of sequential biopsies in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas with the Biomed-2 PCR reveals transient T-cell clones in addition to the tumor clone. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:504–508. doi: 10.1111/exd.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tschumper RC, Asmann YW, Hossain A, Huddleston PM, Wu X, Dispenzieri A, Eckloff BW, Jelinek DF. Comprehensive assessment of potential multiple myeloma immunoglobulin heavy chain V-D-J intraclonal variation using massively parallel pyrosequencing. Oncotarget. 2012;3:502–513. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandberg Y, van Gastel-Mol EJ, Verhaaf B, Lam KH, van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW. BIOMED-2 multiplex immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor polymerase chain reaction protocols can reliably replace southern blot analysis in routine clonality diagnostics. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:495–503. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60580-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang CT, Chuang SS. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with cutaneous involvement: a case report with subtle histologic changes and clonal T-cell proliferation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:e122–124. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-e122-ATLWCI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyata-Takata T, Takata K, Yamanouchi S, Sato Y, Harada M, Oka T, Tanaka T, Maeda Y, Tanimoto M, Yoshino T. Detection of T-cell receptor γ gene rearrangement in paraffin-embedded T or natural killer/T-cell lymphoma samples using the BIOMED-2 protocol. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:2161–2164. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.871634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan BT, Seo K, Warnke RA, Arber DA. The frequency of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene and T-cell receptor gamma-chain gene rearrangements and Epstein-Barr virus in ALK+ and ALK-anaplastic large cell lymphoma and other peripheral T-cell lymphomas. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:502–512. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupuis J, Boye K, Martin N, Copie-Bergman C, Plonquet A, Fabiani B, Baglin AC, Haioun C, Delfau-Larue MH, Gaulard P. Expression of CXCL13 by neoplastic cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL): a new diagnostic marker providing evidence that AITL drives from follicular helper T cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:490–494. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan BT, Warnke RA, Arber DA. The frequency of B- and T-cell gene rearrangements and epstein-barr virus in T-cell lymphomas: a comparison between angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified with and without associated B-cell proliferations. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:466–475. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aung NY, Ohtake H, Iwaba A, Kato T, Ohe R, Tajima K, Nagase T, Yamakawa M. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with dual genotype of TCR and IgH genes. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren YL, Hong L, Nong L, Zhang S, Li T. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis in 15 cases of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;40:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang G, Gao X, Zhao W, Zhang D, Li Y, Li W. Presence of B-cell clones in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2015;44:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The accession numbers or DOIs of any data related to this paper were available in a public database or repository.