Abstract

Background

Geriatric patients are at high risk of Drug Related Problems (DRPs) due to multi- morbidity associated polypharmacy, age related physiologic changes, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics alterations. These patients often excluded from premarketing trials that can further increase the occurrence of DRPs. This study aimed to identify drug related problems and determinants in geriatric patients admitted to medical and surgical wards, and to evaluate the impact of clinical pharmacist interventions for treatment optimization.

Methods

A prospective interventional study was conducted among geriatric patients admitted to medical and surgical wards of Jimma University Medical Center from April to July 2017. Clinical pharmacists reviewed patients drug therapy, identified drug related problems and provided interventions. Data were analyzed by using SPSS statistical software version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were performed to determine the proportion of drug related problems. Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the determinants of drug related problems.

Results

A total of 200 geriatric patients were included in the study. The mean age of the participants was 67.3 years (SD7.3). About 82% of the patients had at least one drug related problems. A total of 380 drug related problems were identified and 670 interventions were provided. For the clinical pharmacist interventions, the prescriber acceptance rate was 91.7%. Significant determinants for drug related problems were polypharmacy (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 4.350, 95% C.I: 1.212–9.260, p = 0.020) and number of comorbidities (AOR = 1.588, 95% C.I: 1.029–2.450, p = 0.037).

Conclusions

Drug related problems were substantially high among geriatric inpatients. Patients with polypharmacy and co-morbidities had a much higher chance of developing DRPs. Hence, special attention is needed to prevent the occurrence of DRPs in these patients. Moreover, clinical pharmacists’ intervention was found to reduce DRPs in geriatric inpatients. The prescriber acceptance rate of clinical pharmacists’ intervention was also substantially high.

Keywords: Geriatrics, Drug related problems, Pharmacist interventions

Background

In developing countries including Ethiopia, life expectancy is increasing. This is partly as a result of increased healthcare seeking behavior in the society and increased access to health service [1, 2]. Related to this, population aging has resulted in an increased prevalence of chronic diseases and thus rise in hospitalizations and healthcare costs of older adults [3].

The geriatric population is at high risk of drug related problems (DRPs) due to the age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes [4]. Furthermore, a higher incidence of drug related problems could result from age associated increased prevalence of multiple chronic diseases, which causes the use of complex therapeutic regimens [5]. According to pharmaceutical care network of Europe (PCNE), DRP is defined as, “an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes” [6]. DRPs are associated with increased healthcare costs and hospital admissions, prolonged hospital stays, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality [7, 8]. Therefore, drug prescribing and use in older patients needs special considerations including avoidance of inappropriate drugs, rational utilization of indicated medications, side effects monitoring, prevention of drug-drug interactions, and evaluation of adherence and patient involvements [9].

The identification, resolution, and prevention of DRPs have been described as a core process of pharmaceutical care. Clinical pharmacists are suitably trained to carry out medication reviews in geriatric patients and have been found to improve the use of high-risk medications and improve the accuracy of medication regimens [10, 11]. In order to resolve DRPs, the cause should be identified and DRPs should be classified appropriately. For such purpose, the classification of DRPs is crucial. There are several classifications for DRPs. However, there is no single standardized classification in the world [12]. The PCNE classification system is commonly practiced and has better usability and internal consistency as it is updated and revised periodically. It is very important for the documentation of DRPs in the pharmaceutical care process [13].

Ethiopia is the second from the top six countries, in which life expectancy and the number of geriatric population is increasing [14] however, there is limited attention for these older patients. Most of the health sciences training programs didn’t include gerontology training in their curriculums and there is no guideline that focuses on geriatric medicine. At the hospital level, geriatric wards are not established for these special populations.

As with other health care services, geriatrics care requires health care professional team work including clinical pharmacists. Experience from developed nations has shown involving clinical pharmacist in patient care resulted in a reduction of DRPs as well as associated costs [15, 16]. Despite the good start up including patient-oriented pharmacy curriculum, clinical pharmacy service is still at the infant stage in Ethiopia. With poor involvement of clinical pharmacists on geriatric care, there is limited information on magnitude of DRPs, determinant factors and clinical pharmacist’s interventions among geriatric patients in hospital set up. Therefore, this study aimed to identify drug related problems and determinants in geriatric patients admitted to medical and surgical wards, and to evaluate the impact of clinical pharmacist interventions for treatment optimization.

Methods

Study design and setting

A prospective interventional study was conducted at medical and surgical wards of Jimma University medical center (JUMC). JUMC is the only teaching and referral hospital with 500 beds in the southwestern part of the country located in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia, 352 km far from Addis Ababa.

Study population

All geriatric patients ≥60 years who were admitted for at least 24 h in the medical and surgical wards of JUMC during the study period (01 April 2017 to 31 July 2017) were included. Geriatrics patients were defined as patients age 60 years and older. Although most developed world countries have accepted the chronological age of 65 years as a definition of ‘elderly’, this does not adapt well to the situation in Africa and it can be extended to 60 years and above [17, 18]. Accordingly, we used the cut point of 60 years old in our study. Geriatric patients re-admitted during the study period and patients who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Data collection

Patients were interviewed using a standard questionnaire and their respective medical chart was reviewed using data abstraction format. Four MSc clinical pharmacists were involved in the identification, interventions and, documentation of DRPs. DRPs were identified by using the following literature resources such as Ethiopian guidelines, European or American standard guidelines such as, American diabetic association for diabetes, American heart associationguideline for heart failure, American urologic association guideline for benign prostatic hyperplasia, world health organization guideline for surgical site infection prophylaxis and other relevant guidelines for the respective diseases identified. Moreover, adverse drug reactions (ADR) were assessed according to the NaranjoADR probability scale [19]. Micromedex was used to check drug-drug interactions. Pharmaceutical care network Europe (PCNE) DRPs classification system was used to classify and document DRPs [6]. For the identified DRPs, intervention was provided through discussion with individual prescriber immediately. Additionally, recommendations were forwarded during rounds and morning sessions orally and/or with written documents and the prescriber acceptance documented. DRPs which are not accepted were further discussed with a senior physician for confirmation. The acceptance of the recommended interventions was followed to check for their implementations and the status of the intervention was documented.

Outcome measure

We have two main objectives in the study. The first objective is to measure the prevalence and determinates of DRPs among geriatric population attending surgical and internal medicine wards of JUMC. The second objective of the study is measuring the impact of clinical pharmacy intervention on reducing the number of DRPs and the acceptance rate of clinical pharmacists’ intervention by prescribers.

Explanatory variables

DRPs were identified by evaluating the appropriateness of drug therapy in terms of indication, dosage, safety, and efficacy. For the identified DRPs, the clinical pharmacists provided interventions. Clinical pharmacist interventions were defined as any action by a clinical pharmacist that directly results in a change of patient management. The Pharmaceutical care network Europe DRPs classification system [6] used in this study have different parts that include: i) The problems(e.g. effect of drug treatment not optimal, unnecessary drug-treatment), ii) causes (e.g., drug dose too low, wrong drug administered, inappropriate timing or dosing intervals), iii) planned interventions (e.g. intervention discussed with prescriber, patient (drug) counselling), iv) acceptance of the intervention proposals (intervention accepted or not accepted) and v) outcome of the intervention (problem solved, partially solved or unsolved). Different interventions were applied for some of the DRPs that resulted in the number of interventions greater than the number of DRPs.

The other variables assessed were (1) socio-demographics (including sex, age, financial status, educational level, residence, marital status, and social support) (2) disease related factors (diagnosis, co-morbidities) and (3) drug/therapy related factorsthat include (polypharmacy, class and type of drugs).Poly-pharmacy was considered when the patients were prescribed with five or more drugs together. Patients who had one or more additional disease condition in addition to the main disease were considered as having comorbidity.

Statistical analyses

EpiData version 4.0.2. for data entry and Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20 (IBM SPSS version 20.0 Inc., Chicago, Illinois) were used for data analysis. Categorical variables were expressed in terms of frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were presented using mean and standard deviation. The proportion of DRPs and prescriber’s acceptance rate of the intervention were reported using these descriptive statistics. Univariable logistic regression analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the potential determinant of DRPs. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 200 patients were included in the final analysis. Of this, 135(67.5%) were male, the mean (SD) age was 67.3 (7.5) years, and the majority (68.5%) of the patients were from rural areas. Two third of the patients did not have a formal education and only 36.5% of the patients had a monthly income of ≥800 Ethiopian Birr. Furthermore, 75% of them relied on the caregiver (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Socio-Demographic Characteristics of geriatric patients admitted from April to July to Medical and Surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017 (N = 200)

| Demographic characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 67.3 (7.3) |

| Sex male | 135 (67.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 158 (79) |

| Widowed | 36 (18) |

| Divorced | 6 (3) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 50 (25) |

| Muslim | 150 (75) |

| Educational status | |

| No formal education | 132 (66) |

| Primary education | 55 (27.5) |

| Secondary education | 8 (4) |

| Tertiary education | 5 (2.5) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 137 (68.5) |

| Urban | 63 (31.5) |

| Monthly income | |

| < 800 birr | 127 (63.5) |

| ≥ 800 birr | 73 (36.5) |

| Relies on caregiver (yes) | 150 (75%) |

Clinical and medication characteristics

The majority (65. 5%) of the patients were admitted to the medical ward. Participants had an average of 2.20 (SD1.57) clinical conditions and they took an average of 3.90 (SD2.11). The most common medical condition was heart failure (24%) followed by stroke (13%) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (11%). Polypharmacy was present in 35.5% of the patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical, and medication related characteristics in geriatric patients admitted from April to July at Medical and Surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017 (N = 200)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Admission ward | |

| Medical | 131 (65.5) |

| Surgical | 69 (34.5) |

| Mean number of disease condition per patient, Mean (SD) | 2.20 (1.157) |

| Mean number of medications per patient, Mean (SD) | 3.9 (2.108) |

| Polypharmacy (yes) | 71 (35.5) |

| Disease conditions | |

| Heart failure | 48 (24) |

| BPH | 26 (13) |

| Stroke | 22 (11) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 13 (6.5) |

| Acute abdomen | 12 (6) |

| Type II DM | 11 (5.5) |

| Cancer | 9 (4.5) |

| Pneumonia | 8 (4) |

| Surgical site infection | 8 (4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (3.5) |

| Trauma | 6 (3) |

| Hernia | 5 (2.5) |

| Hematoma | 5 (2.5) |

| Gangrene | 5 (2.5) |

| Upper GI bleeding | 5 (2.5) |

| Others | 10 (5) |

Prevalence of drug related problems

A total of 380 DRPs were identified from 81.5% of the study participants. Every patient had an average of 1.90 (SD1.47) DRPs. The most commonly found DRPs belonged to the treatment effectiveness related (effect of drug treatment not optimal, untreated indication, and no effect of drug treatment) with 47.6%, followed by (unnecessary drug treatment, problem with the cost-effectiveness of treatment) 28.2%, and adverse drug event 24.2%. Regarding the number of DRPs, 24.5% had one, 26.5% of patients had two, and 30.5% had three and more DRPs (Table 3). Some examples and description of DRPs were provided in Table 4.

Table 3.

DRP categories and number of DRPs among geriatric patients admitted from April to July to Medical and Surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017

| Total number of DRPs =380 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Problem domains | |

| P1: treatment effectiveness (3 categories) | 181 (47.6%) |

| Suboptimal effect of drug treatment | 102 (56.4) |

| Untreated indication | 69 (38.1) |

| No effect of drug treatment | 10 (5.5) |

| P2: treatment safety | 92 (24.2%) |

| Adverse drug event (possibly) occurred | 92 (100) |

| P3: Others | 107 (28.2%) |

| Unnecessary drug treatment | 81 (75.7) |

| Problem with cost effective treatment | 26 (24.3) |

| Number of drug related problems | Frequency (%) |

| None | 37 (18.5) |

| One | 49 (24.5) |

| Two | 53 (26.5) |

| ≥ three | 61 (30.5) |

Table 4.

Some examples of DRPs among geriatric patients admitted from April to July to Medical and Surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017

| Drug related problem | Category of DRPs | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A patient in the age range of 60–70 was admitted to surgical ward with the diagnosis of breast cancer. After one side mastectomy was done, the patient was prescribed with Tamoxifen 20 mg po daily. | Untreated indication | Patient complained severe pain which is 8/10. However, the pain was not treated. Patient has untreated indication and needs morphine 2.5 mg every four hour. |

| A patient in the age range of 60–70 was admitted to internal medicine ward with the diagnosis of ischemic heart disease (NST Elevated myocardial infarction). The patient was prescribed with Simvastatin 40 mg | Suboptimal effect of drug treatment | High intensity statins are required for patients with NSTEMI. Simvastatin 40 mg is medium intensity statin. Thus, it will have suboptimal effect. Therefore, we recommended Atorvasatin 80 mg. |

| A patient in the age range of 70–80 admitted with the diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease. After admission the patient prescribed with warfarin 5 mg and Heparin 12,500 IU |

No effect of drug treatment (Warfarin and Heparin) Untreated indication |

Warfarin and Heparin have no effect on peripheral arterial. Patient needs Atorvastatin and Aspirin to treat his condition. |

| Known cardiac patient in the age of 80–90 was admitted to internal medicine ward. The patient was taking aspirin and lost around 3 l of blood. | Adverse drug event (possibly) occurred | Aspirin was considered the offensive drug and discontinued for 07 days. The bleeding stopped after aspirin was discontinued. Based on Naranjo scale the bleeding is possibly due to Aspirin. |

Causes of drug related problems

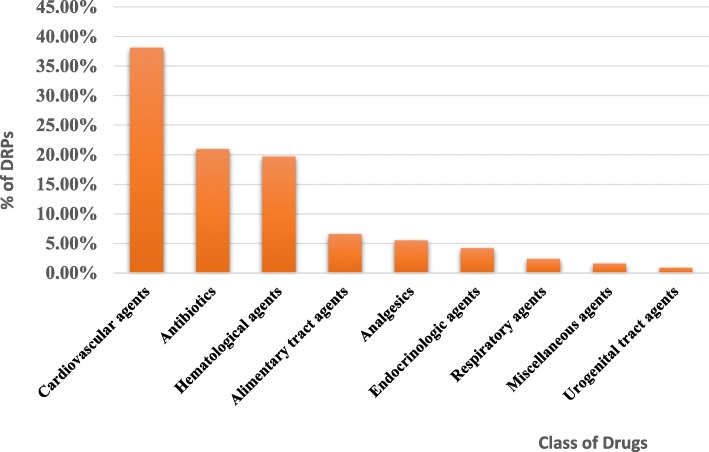

Four hundred sixty six causes of DRPs were identified. Of this, the most common causes of DRPs were inappropriate drug selection (54.1%) followed by inappropriate dose selection (14.6%) and drug use process (12.2%). Among the inappropriate drug selection causes, the presence of new indication for drug treatment (36.1%) was the most common cause followed by no indication for the prescribed drug (20.6%), and inappropriate drug according to guidelines (16.7%) (Table 5). The most frequently involved class of drugs in DRPs were cardiovascular agents (38.1%) followed by antibiotics (21%), and hematological agents (19.7%) (Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Causes of DRPs identified in geriatric patients admitted from April to July to Medical and Surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017

| Cause domain (8 categories) total = 466 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| C1: Drug selection causes | 252 (54.1) |

| New indication for drug treatment | 91 (36.1) |

| No indication for drug | 52 (20.6) |

| Inappropriate drug according to guidelines | 42 (16.7) |

| Contra-indicated | 30 (11.9) |

| Inappropriate duplication of therapeutic | 20 (7.9) |

| Inappropriate combination of drugs, or drugs and food | 17 (6.8) |

| C2: Drug form causes | 16 (3.4) |

| In appropriate drug form | 16 (100) |

| C3: dose selection causes | 68 (14.6) |

| Drug dose too high | 46 (67.6) |

| Drug dose too low | 22 (32.4) |

| C4: treatment duration causes | 24 (5.2) |

| Duration of treatment too long | 22 (91.7) |

| Duration of treatment too short | 2 (8.3) |

| C5: dispensing causes | 20 (4.3) |

| Prescribed drug not available | 18 (90) |

| Prescribing error (necessary information missing) | 2 (10) |

| C6: drug use process causes | 57 (12.2) |

| Drug not administered at all | 40 (70.2) |

| Drug under administered | 11 (19.3) |

| Drug over administered at all | 6 (10.5) |

| C7: patient related causes | 22 (4.7) |

| Patient uses unnecessary drug | 7 (31.8) |

| Patient administered/uses drug in a wrong way | 5 (22.7) |

| Patient cannot afford drug | 5 (22.7) |

| Patient unable to use drug/form as directed | 5 (22.7) |

| C8: other causes | 7 (1.5) |

| No or inappropriate outcome monitoring | 7 (100) |

Fig. 1.

Class of drugs involved in drug related problems in geriatric patients admitted from April to July to medical and surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017

Clinical pharmacist interventions

For identified DRPs, a total of 670 interventions were provided at different levels. Most of the interventions (41%) were provided at the prescriber level, followed by 39.1% at drug level, and 16.1% at patient/caregiver level. At the prescriber level, interventions proposed and discussed with the prescriber were the commonest (82.7%) form of intervention. Out of the interventions carried out at the drug level, the drug stopped and a new drug started was the most common with 30.5% each of them. The prescriber’s acceptance rate was calculated considering the interventions provided at the prescriber level. Accordingly, out of 300 interventions performed at the prescriber level, 275(91.7%) of them were accepted. After the implementation of the interventions, out of the total DRPs, 65.8% of the problems were solved while 27.6% of the problems were not solved (Table 6).

Table 6.

Intervention, prescriber acceptance rate, and outcome of intervention for DRPs among geriatric patients admitted from April to July to Medical and Surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017

| Intervention domain (N = 731) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| I0: No intervention | 61 (8.3) |

| I1: intervention at prescriber level | 300 (41.0) |

| Intervention proposed and discussed with prescriber | 248 (82.7) |

| Prescriber informed only | 52 (17.3) |

| I2: intervention at patient /care giver level | 108 (16.1) |

| Patient drug counseling | 84 (77.8) |

| Spoken to family /care giver | 24 (22.2) |

| I3: intervention at drug level | 262 (39.1) |

| Drug stopped | 80 (30.5) |

| New drug started | 80 (30.5) |

| Dosage changed | 40 (15.3) |

| Drug changed | 33 (12.6) |

| Instruction for use changed | 17 (6.5) |

| Formulation changed | 12 (4.6) |

| I4: other intervention or activity | 0 |

| Intervention acceptance domain (N = 300) | |

| A1: intervention accepted at prescriber level | 275 (91.7) |

| Intervention accepted and fully implemented | 249 (90.5) |

| Intervention accepted but not implemented | 23 (8.4) |

| Intervention accepted, implementation unknown | 0 |

| Intervention accepted and partially implemented | 3 (0.1) |

| A2: intervention not accepted | 25 (8.3) |

| Intervention not accepted; no agreement | 24 (96) |

| Intervention not accepted not feasible | 1 (4) |

| A3: other (no intervention on acceptance) | 0 |

| Problem status domain (N = 380) | |

| O0: problem status unknown | 5 (1.3) |

| O1: problem totally solved | 250 (65.8) |

| O2: problem partially solved | 20 (5.3) |

| O3: problem not solved | 105 (27.6) |

| Lack of coordination of prescriber | 56 (53.3) |

| No possibility to solve problem | 47 (44.8) |

| Lack of coordination of patient | 2 (1.9) |

Determinants of drug related problems

In the multivariable logistic regression model, number of disease condition (AOR = 1.588, 95%CI = 1.029–2.450) and polypharmacy (AOR = 3.350, 95% CI = 1.212–9.260) have statically significant association with DRPs. Patients who took five or more medications (polypharmacy) are 3.350 times more likely to have DRPs than those who took less than five medications. Moreover, as clinical condition increases by one unit the likelihood of developing DRPs increases by 58.8% (Table 7).

Table 7.

Determinants of DRPs among geriatric patients admitted from April to July to medical and surgical wards of JUMC, Ethiopia, 2017

| Univariable logistic regression analysis | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinants | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P value | COR (95% C.I) | P value | AOR (95% C.I) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 108 (66.3) | 27 (73 s) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 55 (33.7) | 10 (27) | 0.43 | 1.37 (0.62–3.04) | 0.33 | 1.6 (0.62–4.12) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 128 (78.5) | 30 (81.1) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced | 4 (2.5) | 2 (5.4) | 0.39 | 0.47 (0.08–2.68) | 0.72 | 1.2 (0.4–3.9) |

| Widowed | 31 (19) | 5 (13.5) | 0.48 | 1.45 (0.52–4.04) | 0.12 | 5.7 (0.6–52) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Educated | 56 (34.4) | 12 (32.4) | Reference | Reference | ||

| No formal education | 107 (65.6) | 25 (67.6) | 0.82 | 1.09 (0.51–2.33) | 0.42 | 1.2 (0.4–3.2) |

| Reliance on care giver | ||||||

| No | 39 (23.9) | 11 (29.7) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 124 (76.1) | 26 (70.3) | 0.463 | 1.35 (0.61–2.96) | 0.55 | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) |

| Economic status | ||||||

| ≥ 800 Birr | 61 (37.4) | 12 (32.4) | Reference | Reference | ||

| < 800 Birr | 102 (62.6) | 25 (67.6) | 0.57 | 0.80 (0.38–1.71) | 0.48 | 1.4 (0.5–3.6) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 52 (31.9) | 11 (29.7) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rural | 111 (68.1) | 26 (70.3) | 0.79 | 0.903 (0.415–1.966) | 0.47 | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) |

| Polypharmacy | ||||||

| No | 97 (59.5) | 32 (86.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 66 (40.5) | 5 (13.5) | 0.004 | 4.36 (1.61–11.75) | 0.02 | 3.35 (1.21–9.26) |

| Comorbidities, mean (SD) | 2.20 (1.157) | 0.006 | 1.79 (1.18–2.71) | 0.04 | 1.588 (1.03–2.45) | |

COR Crude odds ratio, AOR Adjusted odds ratio, CI Confidence Interval

Discussion

Drug related problems are becoming a major public health concern. Geriatric patients are particularly highly vulnerable to DRPs caused by multiple factors such as polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing [20]. Identification and prevention of DRPs occurrence in this population is crucial. In our study, DRPs were present in 81.5% of the geriatric patients. This is in line with a study conducted by Ramanath K et al. in internal medicine rural tertiary care hospital of India, which showed an 83.4% prevalence of DRPs [21].

Our study identified an average of 1.90 ± 1.47 DRPs per participant. This is somewhat lower than a study conducted by Chan et al. in Thailand, which showed an average of 2.2 ± 1.6 DRPs per participant [22]. This can be explained by the setting difference. Our study was conducted in hospitalized patients where frequents patients visit by senior physicians and residents were applicable whereas the study in Thailand was conducted on outpatients where patients were less likely to meet senior physicians frequently. More than half (54.1%) of the DRPs resulted from inappropriate drug selection. Among the causes of inappropriate drug selection, having a new indication for drug treatment accounted for a higher proportion (36.1%). This is in line with an interventional study done in Belgium in geriatric wards, which reported the most frequent DRPs was an underuse of medications [23].

After the identification and characterization of DRPs, interventions were proposed by the clinical pharmacists. Interventions were provided at prescriber level, at patient /caregiver level, and at drug level. The physician’s acceptance rate of the clinical pharmacist’s recommendations was determined based on the intervention acceptance rate at the prescriber level. Accordingly, the prescriber acceptance rate was high (91.7%). This is in line with a study conducted in Belgium (87.8%) [23]. This finding has important implications for participating clinical pharmacists as part of the multidisciplinary team, can facilitate the identification of DRPs among geriatric patients and inform physicians to resolve the problems.

Another purpose of our study was to identify the determinants of DRPS. We found that patients with polypharmacy were more likely to develop DRPs than without polypharmacy. In accordance with the present results, previous studies [23, 24] have demonstrated that polypharmacy was a major determinant for the occurrence of DRPs. The observed association of polypharmacy with DRPs in geriatric patients could be as a result of increased health-care costs for the multiple medications, drug-interactions, disability/cognitive impairment, noncompliance to medications, increased risk of adverse drug events, falls and fractures, malnutrition, and functional status decline [3, 25]. We also found that patients having one or more co-morbidities had more DRPs. This finding is in agreement with Tegegneet al [26], the finding which showed patients with comorbidities were at high risk of DRPS.

After the implementation of the clinical pharmacists’ interventions, the status of DRPs was determined. The interventions solved around two-third (65.8%) of the existed drug related problems. However, around 27.6% of the DRPs remained unsolved as a result of lack of coordination of prescribers, no possibility to solve the DRPs and lack of coordination of the patients. These results are consistent with those of other studies which were able to solve 58.9–68.3% of identified drug related problems [23].

Conclusion

Drug related problems were substantially high among geriatric inpatients. Patients with polypharmacy and co-morbidities had a much higher chance of developing DRPs. Hence, special attention is needed to prevent the occurrence of DRPs in these patients. Moreover, clinical pharmacists’ intervention was found to reduce DRPs in geriatric inpatients. The prescriber acceptance rate of clinical pharmacists’ intervention was also substantially high.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank study participants, data collectors, and study hospital administrators who contributed to this study.

Abbreviations

- ADR

Adverse drug reaction

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- DRPs

Drug related problems

- JUMC

Jimma university medical center

- PCNE

Pharmaceutical care network europe

- SD

Standard deviation

- WHO

World health organization

Authors’ contribution

B.Y designed and performed the research, analyzed, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. M.G., D.F.B, E.K.G., KG were involved in study design, data analysis, and manuscript evaluation. All authors read and accepted the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by Jimma University (grant number: clipharm03). The funding body had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of this manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance and approval of the study were obtained from Jimma University, Institute of Health ethical review board before starting the actual data collection. Subsequent permission was granted from Jimma University Medical Center to access medical records. Participation of patients in this study was entirely voluntary. Confidentiality of the collected data was ensured through anonymity. Each participant was asked to sign a written informed consent before data collection. The right of participants to withdraw from the interview or not to participate was respected. Patient’s privacy kept while interviewing.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dwolatzky T. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. Jama. 2009;302(16):1813. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World health organization: World report on Ageing and Health 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/. Accessed 5 Jan 2019.

- 3.Nobili A, Garattini S, Mannucci PM. Multiple diseases and polypharmacy in the elderly: challenges for the internist of the third millennium. J Comorbidity. 2011;1:28–44. doi: 10.15256/joc.2011.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(1):6–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva C, Ramalho C, Luz I, Monteiro J, Fresco P. Drug-related problems in institutionalized, polymedicated older patients: opportunities for pharmacist intervention. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(2):327–334. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-0063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe. Classification for drug related problems; 2017. Available from: https://www.pcne.org/working-groups/2/drug-related-problem-classification. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

- 7.Naples JG, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Semla TP. Recent literature on medication errors and adverse drug events in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):401–408. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvi F, Marchetti A, D’Angelo F, Boemi M, Lattanzio F, Cherubini A. Adverse drug events as a cause of hospitalization in older adults. Drug Saf. 2012;35(1):29–45. doi: 10.1007/BF03319101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL, Swine C, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weddle SC, Rowe AS, Jeter JW, Renwick RC, Chamberlin SM, Franks AS. Assessment of clinical pharmacy interventions to reduce outpatient use of high-risk medications in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(5):520–524. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Sullivan D, O’Mahony D, O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, Cullinan S, O’Sullivan R, et al. The impact of a structured pharmacist intervention on the appropriateness of prescribing in older hospitalized patients. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(6):471–481. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basger BJ, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Development of an aggregated system for classifying causes of drug-related problems. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(4):405–418. doi: 10.1177/1060028014568008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Mil JF, Westerlund LT, Hersberger KE, Schaefer MA. Drug-related problem classification systems. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(5):859–867. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World health organization. World Health Statistics 2014, Large gains in life expectancy 2014 [cited 2017 3/27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/world-health-statistics-2014/en/. Accessed 14 May 2019.

- 15.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Characteristics of drug-related problems discussed by hospital pharmacists in multidisciplinary teams. Pharm World Sci : PWS. 2006;28(3):152–158. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado Silveira E, Fernandez-Villalba EM, Garcia-Mina Freire M, Albinana Perez MS, Casajus Lagranja MP, Peris Marti JF. The impact of pharmacy intervention on the treatment of elderly multi-pathological patients. Farm Hosp : Organo Oficial de expresion cientifica de la Sociedad Espanola de Farm Hosp. 2015;39(4):192–202. doi: 10.7399/fh.2015.39.4.8329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanath K, Nedumballi S. Assessment of medication-related problems in geriatric patients of a rural tertiary care hospital. J Young Pharm : JYP. 2012;4(4):273–278. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.104372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World health organization. Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project 2002 [cited 2017 04/10/2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/. Accessed 20 Mar 2019.

- 19.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts E, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freyer J, Hueter L, Kasprick L, Frese T, Sultzer R, Schiek S, et al. Drug-related problems in geriatric rehabilitation patients after discharge – A prevalence analysis and clinical case scenario-based pilot study. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2018;14(7):628–37. 21. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramanath K, Nedumballi S. Assessment of medication-related problems in geriatric patients of a rural tertiary care hospital. J Young Pharm: JYP. 2012;4(4):273. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.104372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan D-C, Chen J-H, Kuo H-K, We C-J, Lu I-S, Chiu L-S, et al. Drug-related problems (DRPs) identified from geriatric medication safety review clinics. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spinewine A, Dhillon S, Mallet L, Tulkens PM, Wilmotte L, Swine C. Implementation of ward-based clinical pharmacy services in Belgium—description of the impact on a geriatric unit. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(4):720–728. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT. To err is human: building a safer health system: National Academies Press. 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maher Robert L, Hanlon Joseph, Hajjar Emily R. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2013;13(1):57–65. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tegegne GT, Gelaw BK, Defersha AD, Yimam B, Yesuf E. Drug therapy problem among patients with cardiovascular diseases in Felege Hiwot referral hospital, northeast. Bahir Dar Ethiopia IAJPR. 2014;4:2828–2838. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.