Abstract

Critical limb ischemia (CLI) represents the most severe manifestation of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). It imposes a huge economic burden and is associated with high short-term mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Prompt recognition and early revascularization, surgical or endovascular, with the aim of improving the inline bloodflow to the ischemic limb, are currently the standard of care. However, this strategy may not always be feasible or effective; hence, evaluation of newer pharmacological or angiogenic therapies for alleviating the symptoms of this alarming condition is of utmost importance. Cell-based therapies have shown promise in smaller studies; however, large-scale studies, demonstrating definite survival benefits, are entailed to ascertain their role in the management of CLI.

Keywords: Critical limb ischemia, peripheral arterial disease, stem cell therapy

Introduction

Critical limb ischemia (CLI) represents the most severe and probably an end-stage manifestation of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and is still considered an orphan disease with no effective medical treatment. It constitutes a considerable social and economic burden and is associated with a dismal prognosis. CLI may develop from many fundamentally distinct pathophysiological processes, including, more commonly, advanced atherosclerosis and, less commonly, thromboembolism, in situ thrombosis, and the arthritides. It is associated with high short-term mortality, as well as adverse cardiovascular events.[1,2] Revascularization, wherever feasible, is the cornerstone of therapy; however, major amputations and death remain the most frequent complications. Considerable major amputation rates in the range of 10–40% have been seen in these patients, particularly with failed revascularization or in those with “no-option” CLI.[3,4,5] Exploring newer approaches for revascularization of these ischemic limbs is therefore of prime importance. Cell-based therapies have come into view as a new frontier in this direction and bone marrow-derived stem cells (BM-SC) are currently seen as a prospective and possible newer therapeutic option in this regard.

Therapeutic Angiogenesis

Therapeutic angiogenesis with BM-SC or progenitor cells is currently being explored in the management of CLI with great enthusiasm because of promising early results in various preclinical trials. Clinical benefits reported from the use of stem cells in these studies include improvement in the ankle-brachial index (ABI), transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen (TcPO2), reduction of pain, and reduced rates of limb amputation. Ongoing research pertains to the cell isolation method, suitable cell source, optimal cell type, right dosage, administration route, and identification of optimal measures of outcomes for these therapies.

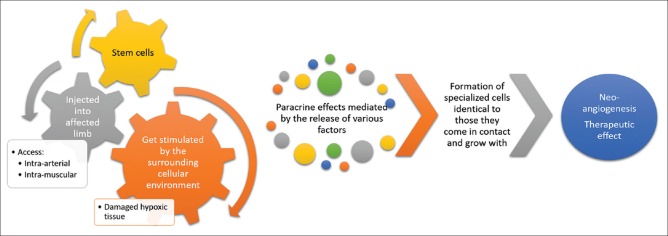

Stem cells have tremendous potential to differentiate and evolve into differentiated cell types. Whenever the stem cell divides, each newer cell can remain as a stem cell or develop into a different cell type with a highly specialized function. The majority of cell-based therapies in experimental or clinical use generally include embryonic stem cells, cord blood cells, cells from the blastocysts, or the adult stem cells. The stem cells gradually get stimulated by the surrounding cellular environment (damaged hypoxic tissues) that leads to the formation of specialized cells identical to those they come in contact and grow with. Paracrine effects mediated by the release of various factors (cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors) are largely responsible for these reparative processes, particularly neoangiogenesis [Figure 1]. By the virtue of this, these cells are able to become newer blood vessels, BM, neurons, pancreas, etc., depending upon the local tissue characteristics and milieu. The safety and efficacy of endovascular delivery of these BM-SC have been evaluated in various studies in the treatment of patients with chronic disease states, such as CLI, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic renal failure, cerebral palsy (CP), muscle dystrophy (MD), spinal cord injury, and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).[6,7,8,9,10,11]

Figure 1.

Therapeutic angiogenesis with stem cell therapy

Stem cell retrieval and injection

BM aspiration from the posterior iliac crest is usually preferred in adult patients as it is readily accessible, safe, and less traumatic.[12] Moreover, it usually yields adequate representative sample. Other sites may include the sternum, vertebral spine, and anterior iliac crest. Separation and injection of stem cells are usually preferred on the day of aspiration. These cells may be injected intramuscularly (IM) or intraarterially (IA) or using the combined IM/IA route. The stem cell injection with a predetermined dose is usually targeted at the disease site, such as occluded vascular segment in CLI, the pancreaticoduodenal artery in DM, spinal artery in cord injury, extremity artery in MD, coronary artery in cases of DCM, and internal carotid artery in CP patients. Follow-up may be done at 1, 3, and 6 months and annually thereafter with preset endpoints depending on the initial indication. These endpoints may include ulcer healing, rest pain relief, improvement in claudication free walking distance, enhancement of collaterals formation on imaging, and upgradation of quality of life (QOL) in CLI patients.

Effectiveness of therapy

Many studies have shown the effectiveness of stem cell therapy in CLI patients, including randomized trials, nonrandomized trials, and noncontrolled studies. However, owing to the heterogeneity among various studies, limited sample sizes and lack of large-scale placebo-controlled studies, acceptance of this mode of therapy as the standard of care is still a matter of debate. Transplantation of autologous BM-SC has also been evaluated in terms of different approaches for the implantation, viz. IM injection, IA injection, or combined, and has shown nearly similar results in this aspect.[13] BM stimulation using an injection of the recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has also shown to be advantageous in terms of higher concentration of mononuclear cells (MCs) requiring lesser aspirations with satisfactory short-term effects.[14] Moreover, a comparative study on autologous injection using peripheral blood stem cells (PB-SCs) or BM-SC has also shown similar efficacy in treating lower limb ischemia.[15]

The first substantial report using IM autologous BM-MCs in limb ischemia came from the Therapeutic Angiogenesis Using Cell Transplantation (TACT) study. The study showed a 60% (95% confidence interval [CI], 46–74) 3-year amputation-free rate; and significant improvement in the clinical assessments of leg pain, ulcer size, and claudication free walking distance, which was sustained till at least 2 years after the therapy, although the change in the objective parameters of ABI and TcPO2 was not statistically significant.[16]

Bone Marrow Outcomes Trial 1 (BONMOT-1) demonstrated an increase in leg perfusion with a reduction in amputation rates in 51 “no-option” CLI patients transplanted IM with autologous BM cells into the ischemic leg.[17] 59% and 53% of the limbs were salvaged at 6 months and at the last follow-up (range 175–1186 days) respectively, with increase in ABI (0.33 ± 0.18 to 0.46 ± 0.15) and TcPO2 (12 ± 12 to 25 ± 15 mm Hg) noted at 6 months. The mean Rutherford category improved from 4.9 (baseline) to 3.3 (6 months) using P = 0.0001, with the reduction in the analgesic consumption by 62% and improvement in total walking distance from 0 to 40 m. In both the BONMOT-1 and BONMOT-CLI, which was an ensuing double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the BM-MNC injections were given along the anatomic course of the occluded arteries. This maximizes their impact as the density of the preexisting collaterals is presumed to be highest in these regions.[18] Moreover, in the BONMOT-1 and BONMOT-CLI, the length of the occlusion determined the number of such injections.

The RESTORE-CLI trial of 77 lower limb CLI patients compared IM injection of ixmyelocel-T (patient-specific, expanded, and multicellular therapy) to placebo.[19] The trial showed significant improvement in the time duration of first treatment failure (P = 0.0032, logrank test). Although there was a 32% decrease in amputation-free survival, this result was not statistically significant (P = 0.3). The effect of treatment in those with wounds at baseline was more marked.[19] The interim analysis of the HARVEST trial also showed an improving trend in the control of major amputations, pain improvement, QOL score, ABI, and Rutherford classification in the BM aspirate concentrate group as compared with the controls.[20]

The PROVASA trial (randomized-start, placebo-controlled pilot trial) randomized 40 patients with CLI to IA delivery of either BM-MNC or placebo followed by active treatment at 3 months with BM-MNC.[21] Though the study showed significant improvement in rest pain and ulcer healing in the BM-MNC group, patients with gangrene or considerable tissue loss at baseline were nonresponders. Another relevant conclusion from the study was that multiple treatments were more effective than a single treatment. From the therapy perspective, a higher number of BM-MNC delivered with repeated administration and greater functionality predicted ulcer healing.

No treatment-related adverse reactions were noted in another study that compared combined IM and IA (n = 15) delivery of autologous BM-MNC with exclusive IM (n = 12) injections in patients with CLI.[22] Although only two patients in the combined group versus seven patients in the IM group needed amputation, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.17). Sustained significant improvement in clinical and objective parameters was seen in rest of the patients during follow-up. The transplantation of autologous mononuclear BM stem cells in patients with peripheral arterial disease (TAM-PAD) study has also shown similar results.[23] However, similar results are seen in another study comparing the mode of implantation of stem cells with no statistically significant difference.[13] Various preclinical studies have shown the role of stromal-cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1) in promoting tissue repair via mechanisms involving neoangiogenesis and stem-cell repair pathways, thus, preventing on-going cell death.[24,25] A phase II clinical trial (JUVENTUS) has been approved to evaluate its safety and efficacy in the treatment of CLI patients.

Other studies evaluating the role of stem cells in CLI patients have been enumerated in Table 1.[26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]

Table 1.

Studies evaluating the role of stem cell therapy in CLI

| Study (Year) | Cell type and route of injection | Broad inclusion criteria | Type of study | Sample size | Duration of follow up (Months) | Significant changes in the treatment group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al.[26] (2005) | IM G-CSF and PB-MNCs |

CLI of diabetic patients | RCT | 28 | 3 | Improvement in ABI, angiographic score, and ulcer healing compared with the control group. No amputation vs 5/14 in the control group. |

| Arai et al.[27] (2006) | IM BM-MNCs vs G-CSF |

Intractable PAD | A negative control group (n=12) treated with GDMT, a positive control group (n=13) treated with GDMT + BM-MNCs and a G-CSF group (n=14) | 39 | 1 | Improvement in subjective symptoms, ABI, and TcPO2 in both BM-MNCs and G-CSF group compared to negative control. |

| Barć et al.[28] (2006) | IM BM-MNCs | Nonrevascularisable CLI not responsive to conventional treatment | Control group (n=15) and those treated with BM cells (n=14) | 29 | 6 | Improvement in subjective symptoms, healing of ulcers. Lesser amputations in the treatment group. |

| Lu et al.[29] (2008) | IM BM-MSCs | Lower limb ischemia in Type 2 diabetes | RCT | 50 | 3 | Ulcer healing rate and ABI more in the treatment group Amputation rate lower. |

| Dash et al.[30] (2009) | IM BM-MSCs | Nonhealing ulcers (Diabetes and Buergers) | RCT | 24 | 3 | Improvement in pain-free walking distance and reduction in ulcer size. |

| Procházka et al.[31] (2010) | IA BM-SCs | CLI patients with foot ulcer | RCT | 96 | 4 | Reduced major amputation rate and improvement in toe brachial index and toe pressure in salvaged limbs of the treatment group. |

| Wen and Huang[32] (2010) | IM PB-SCs | CLI | RCT | 60 | 3 | Improvement in ABI, ulcer healing, and angiographic scores and lower amputation rates in the treatment group. |

| Lu et al.[33] (2011) | IM BM-MSC vs BM-MNC |

Type 2 diabetes with bilateral CLI | BM-MSC or BM-MNC or normal saline | 41 | 6 | Ulcer healing rate; pain-free walking distance; and ABI, TCPO2, and angiographic score of BM-MSC higher than BM-MNC. No difference in pain relief or amputation rate. |

| Jain et al.[34] (2011) | Topically applied and locally injected BM-SC vs whole blood (control) |

Diabetes with chronic ulcer | RCT | 48 | 3 | Increased rate of ulcer healing in the treatment group. |

| Benoit et al.[35] (2011) | IM BM-SCs vs peripheral blood (placebo) | No option CLI | Double-blinded pilot RCT | 48 | 6 | Lower amputation rates and longer time to amputation in the treatment group. |

| Losordo et al.[36] (2012) | IM CD34+ | Nonrevascularisable CLI | RCT 28 patients to 7 to 1 × 105 (low-dose) and 9-1 × 106 (high-dose) autologous CD34+ cells/kg; and 12 to placebo | 40 | 12 | Major and minor amputation rates lowest in the high dose treatment group. |

| Ozturk et al.[37] (2012) | G-CSF mobilized PB-MNCs delivered IM | Diabetes with CLI | RCT | 40 | 3 | Improvement in the Fontaine score, ABI, TCPO2, and 6 min walking distance. A decrease in the pain score and number of ulcers. |

| Gupta et al.[38] (2013) | IM allogeneic BM-MSCs |

CLI | Double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study | 20 | 6 | Improvement in pain score, ABI, and ankle pressure in the treatment group. Serious adverse events similar in both groups. |

| Li et al.[39] (2013) | IM BM-MNCs | CLI | RCT | 58 | 6 | Improvement in rest pain, skin ulcers, and ABI. |

| Mohammadzadeh et al.[40] (2013) | G-CSF mobilised PB-MNCs delivered IM | Diabetes with CLI | RCT | 21 | 3 | Improvement in pain, wound healing, and ABI, and lower amputation rates. |

| Szabo et al.[41] (2013) | IM In vitro expanded PB-SCs | No option for patients with peripheral arterial disease | RCT | 20 | 3 | Improvement in hemodynamic parameters. No deaths or major amputation in the treatment group. |

| Raval et al.[42] (2014) | IM cytokine mobilized CD133+ | CLI | Double-blinded, randomized, sham-controlled trial | 10 | 12 | Trends toward improved amputation-free survival, 6-minute walk distance, walking, and QOL. |

| Skóra et al.[43] (2015) | Autologous BM-MNC and VEGF plasmid vs pentoxifylline | CLI | RCT | 32 | 3 | Significant improvement in ABI, collateralization, ulcer healing. Lower rate of amputation. |

CLI=Critical limb ischemia, IM=Intramuscular, G-CSF=Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, PB-MNCs=Peripheral blood mononuclear cells, RCT=Randomized controlled trial, ABI=Ankle-brachial index, QOL=Quality of life, BM-MNCs=Bone marrow mononuclear cells, PAD=Peripheral arterial disease, GDMT=Guideline-directed management and therapy, TcPO2=Transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen, BM-MSCs=Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, IA=Intramuscular, BMSCs=Bone marrow stem cells, PB-SCs=Peripheral blood stem cells, VEGF=Vascular endothelial growth factor

The latest meta-analysis (19 randomized controlled trials [RCTs], 7 nonrandomized trials, and 41 noncontrolled studies) has shown that autologous cell therapy has the potential to favorably alter the natural history of intractable CLI with better composite clinical outcome, avoidance of amputations, and thus improvement in the QOL.[44] It showed a 37% reduction in the risk of amputation, 18% improvement in amputation-free survival, and 59% improved wound healing and reduction in rest pain without affecting mortality. Moreover, cell therapy has also shown a significant increase in objective indices like ABI and TcPO2. In this analysis, IM implantation fared better than IA infusion and mobilized peripheral blood MNCs (PB-MNCs) were more effective than BM-MNCs and mesenchymal stem cells.

In another meta–analysis, amputation reduction (nearly 60%) and improvement in ulcer healing, ABI, TcO2, pain-free walking capacity, and collateralization have been shown with moderate quality of evidence in patients receiving cell-based therapy compared to those receiving noncell-based therapy with similar all-cause mortality rates (high-quality evidence) noted between the two groups.[45] A meta-analysis of database until January 2018 also demonstrated the effectiveness of cell therapy with significantly increased probability of ulcer healing and angiogenesis with reduced amputation rates. ABI, TcPO2, and pain-free walking distance were significantly better in the cell therapy group than in the control group (P < 0.01).[46] Further, no clear differences have been shown between different stem cell sources, treatment regimens, doses, and routes of administration in terms of outcomes, such as all-cause mortality, amputation rate, ulcer healing, and rest pain for “no-option” CLI patients.[47] However, high-quality evidence is still lacking and needs further substation by larger, long-term studies.

Challenges and limitations of stem cell therapy

Despite encouraging results from multiple studies, many questions and challenges remain unanswered with regard to stem cell therapy, including the exact understanding of the precise molecular mechanisms of the therapy and the identification of the ideal cell type, optimal dosage, route, and frequency of administration. Moreover, we must expand our understanding regarding various tissue endogenous microenvironmental factors, which may affect the in situ differentiation or therapeutic activity of the applied stem cells. Effective and large-scale protocols regardingin vitro cell differentiation need to be established in addition to various efficient methods for augmentation of cell potency, which may include ex vivo stimulation of the stem cells with cytokines and various growth factors, such as hepatocyte and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), SDF-1α, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF).[48,49,50,51,52] Also, the role of autologous versus allogeneic stem cell therapy in CLI needs to be addressed to develop more effective methods to manipulate therapeutic arteriogenesis.[53,54]

Future directions

Overall, the stem cell-based therapy has shown to be safe and effective with mild and, mostly, transient-associated adverse reactions, commonly related to local implantation/injection. Further, the use of preconditioning strategies and sustained release of growth factors via the use of bioactive microspheres may enhance the therapeutic efficacy of cell therapy. Considering the fact that a significant number of patients with CLI may not be a candidate for revascularization, stem cell-based therapy may be a potential candidate as a standard of care as it seems to have the potential to alter the natural history of CLI.

Conclusion

Autologous stem cell therapy is evolving as a promising newer tool in the management of CLI. Initial evidence is supportive of its safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of many important endpoints. However, the acceptance of this mode of therapy as a standard of care is still a matter of debate as its efficacy is not consistent when analyzing only the placebo-controlled randomized trials. Further, large studies meeting important endpoints with definite survival benefit are required to establish its role in the management of CLI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Biancari F. Meta-analysis of the prevalence, incidence and natural history of critical limbischemia. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2013;54:663–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nehler MR, Duval S, Diao L, Annex BH, Hiatt WR, Rogers K, et al. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia in an insured national population. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:686–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.03.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG. Intersociety consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II) J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(suppl S):S5–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varu VN, Hogg ME, Kibbe MR. Critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:230–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertele V, Roncaglioni MC, Pangrazzi J, Terzian E, Tognoni G. Clinical outcome and its predictors in 1560 patients with critical leg ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:401–10. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wester T, Jørgensen JJ, Stranden E, Sandbaek G, Tjønnfjord G, Bay D, et al. Treatment with autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with critical lower limb ischaemia. A pilot study. Scand J Surg. 2008;97:56–62. doi: 10.1177/145749690809700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chochola M, Pytlík R, Kobylka P, Skalická L, Kideryová L, Beran S, et al. Autologous intra-arterial infusion of bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with critical leg ischemia. Int Angiol. 2008;27:281–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirana S, Stratmann B, Prante C, Prohaska W, Koerperich H, Lammers D, et al. Autologous stem cell therapy in the treatment of limb ischaemia induced chronic tissue ulcers of diabetic foot patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:384–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tierney M, Garcia C, Bancone M, Sacco A, Personius KE. Innervation of dystrophic muscle after muscle stem cell therapy. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54:763–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.25115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao M, Wang R, Wang W. Cell therapies in cardiomyopathy: Current status of clinical trials. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) 2017;2017:9404057. doi: 10.1155/2017/9404057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagoshi N, Okano H. Applications of induced pluripotent stem cell technologies in spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2017;141:848–60. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bierman HR. Bone marrow aspiration the posterior iliac crest, an additional safe site. Calif Med. 1952;77:138–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu YQ, Zhang J, Guo LR, Qi LX, Zhang SW, Xu J, et al. Transplantation of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for patients with lower limb ischemia. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008;121:963–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Y, Zhang J, Qi L. A clinical study on implantation of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells after bone marrow stimulation for treatment of lower limb ischemia. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;20:1017–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu Y, Zhang J, Qi L. Comparative study on autologous implantation between bone marrow stem cells and peripheral blood stem cells for treatment of lower limb ischemia. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;21:675–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matoba S, Tatsumi T, Murohara T, Imaizumi T, Katsuda Y, Ito M, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after intramuscular implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (Therapeutic Angiogenesis by Cell Transplantation [TACT] trial) in patients with chronic limb ischemia. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1010–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amann B, Luedemann C, Ratei R, Schmidt-Lucke JA. Autologous bone marrow cell transplantation increases leg perfusion and reduces amputations in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia due to peripheral artery disease. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:371–80. doi: 10.3727/096368909788534942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amann B, Lüdemann C, Rückert R, Lawall H, Liesenfeld B, Schneider M, et al. Design and rationale of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study for autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in critical limb ischemia: The BONe marrow outcomes trial in critical limb ischemia (BONMOT-CLI) Vasa. 2008;37:319–25. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.37.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell RJ, Marston WA, Berceli SA, Guzman R, Henry TD, Longcore AT, et al. Cellular therapy with Ixmyelocel-T to treat critical limb ischemia: The randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled RESTORE-CLI trial. Mol Ther. 2012;2:1280–6. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iafrati MD, Hallett JW, Geils G, Pearl G, Lumsden A, Peden E, et al. Early results and lessons learned from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of bone marrow aspirate concentrate in critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1650–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walter DH, Krankenberg H, Balzer J, Kalka C, Baumgartner I, Schlüter M, et al. Intraarterial administration of bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with critical limb ischemia: A randomized-start, placebo-controlled pilot trial (PROVASA) Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:26–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.958348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Tongeren RB, Hamming JF, Fibbe WE, Van Weel V, Frerichs SJ, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Intramuscular or combined intramuscular/intra-arterial administration of bone marrow mononuclear cells: A clinical trial in patients with advanced limb ischemia. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2008;40:51–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartsch T, Brehm M, Zeus T, Kögler G, Wernet P, Strauer BE. Transplantation of autologous mononuclear bone marrow stem cells in patients with peripheral arterial disease (the TAM-PAD study) Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96:891–9. doi: 10.1007/s00392-007-0569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho TK, Shiwen X, Abraham D, Tsui J, Baker D. Stromal-cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)/CXCL12 as potential target of therapeutic angiogenesis in critical leg ischaemia. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:143209. doi: 10.1155/2012/143209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frangogiannis NG. Stromal cell-derived factor-1- mediated angiogenesis for peripheral arterial disease: Ready for prime time? Circulation. 2011;123:1267–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.021204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang P, Li S, Han M, Xiao Z, Yang R, Han ZC. Autologous transplantation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells improves critical limb ischemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2155–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arai M, Misao Y, Nagai H, Kawasaki M, Nagashima K, Suzuki K, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: A noninvasive regeneration therapy for treating atherosclerotic peripheral artery disease. Circ J. 2006;70:1093–8. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barć P, Skóra J, Pupka A, Turkiewicz D, Dorobisz AT, Garcarek J, et al. Bone-marrow cells in therapy of critical limb ischemia of lower extremities-own experience. Acta Angiologica. 2006;12:155–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debin L, Youzhao J, Ziwen L, Xiaoyan L, Zhonghui Z, Bing C. Autologous transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on diabetic patients with lower limb ischemia. J Med Coll PLA. 2008;23:106–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dash NR, Dash SN, Routray P, Mohapatra S, Mohapatra PC. Targeting nonhealing ulcers of lower extremity in human through autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12:359–66. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Procházka V, Gumulec J, Jalůvka F, Salounová D, Jonszta T, Czerný D, et al. Cell therapy, a new standard in management of chronic critical limb ischemia and foot ulcer. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:1413–24. doi: 10.3727/096368910X514170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wen JC, Huang PP. Autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells transplantation in treatment of 30 cases of critical limb ischemia: 3-year safety follow-up. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res. 2010;14:8526–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu D, Chen B, Liang Z, Deng W, Jiang Y, Li S, et al. Comparison of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells for treatment of diabetic critical limb ischemia and foot ulcer: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain P, Perakath B, Jesudason MR, Nayak S. The effect of autologous bone marrow-derived cells on healing chronic lower extremity wounds: Results of a randomized controlled study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2011;57:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benoit E, O’Donnell TF, Jr, Iafrati MD, Asher E, Bandyk DF, Hallett JW, et al. The role of amputation as an outcome measure in cellular therapy for critical limb ischemia: Implications for clinical trial design. J Transl Med. 2011;9:165. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Losordo DW, Kibbe MR, Mendelsohn F, Marston W, Driver VR, Sharafuddin M, et al. Autologous CD34+ Cell Therapy for Critical Limb Ischemia Investigators. A randomized, controlled pilot study of autologous CD34+cell therapy for critical limb ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:821–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.968321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozturk A, Kucukardali Y, Tangi F, Erikci A, Uzun G, Bashekim C, et al. Therapeutical potential of autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with type 2 diabetic critical limb ischemia. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta PK, Chullikana A, Parakh R, Desai S, Das A, Gottipamula S, et al. A double blind randomized placebo controlled phase I/II study assessing the safety and efficacy of allogeneic bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cell in critical limb ischemia. J Transl Med. 2013;11:143. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Zhou H, Jin X, Wang M, Zhang S, Xu L. Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells transplant in patients with critical leg ischemia: Preliminary clinical results. Exp Clin Transplant. 2013;11:435–9. doi: 10.6002/ect.2012.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohammadzadeh L, Samedanifard SH, Keshavarzi A, Alimoghaddam K, Larijani B, Ghavamzadeh A, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of transplanting autologous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilised peripheral mononuclear cells in diabetic patients with critical limb ischaemia. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121:48–53. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szabó GV, Kövesd Z, Cserepes J, Daróczy J, Belkin M, Acsády G. Peripheral blood-derived autologous stem cell therapy for the treatment of patients with late-stage peripheral artery disease-results of the short- and long-term follow-up. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:1245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raval AN, Schmuck EG, Tefera G, Leitzke C, Ark CV, Hei D, et al. Bilateral administration of autologous CD133+cells in ambulatory patients with refractory critical limb ischemia: Lessons learned from a pilot randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:1720–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skóra J, Pupka A, Janczak D, Barć P, Dawiskiba T, Korta K, et al. Combined autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell and gene therapy as the last resort for patients with critical limb ischemia. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:325–31. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.39935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rigato M, Monami M, Fadini GP. Autologous cell therapy for peripheral arterial disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, non-randomized, and non-controlled studies. Circ Res. 2017;120:1326–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahid FSA, Ismail NA, Wan Jamaludin WF, Muhamad NA, Mohamad Idris MA, Lai NM. Efficacy and safety of autologous cell-based therapy in patients with no-option critical limb ischaemia: A meta-analysis. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;13:265–83. doi: 10.2174/1574888X13666180313141416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie B, Luo H, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Zhou C, Xu D. Autologous stem cell therapy in critical limb ischemia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:7528464. doi: 10.1155/2018/7528464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdul Wahid SF, Ismail NA, Wan Jamaludin WF, Muhamad NA, Abdul Hamid MKA, Harunarashid H, et al. Autologous cells derived from different sources and administered using different regimens for 'no-option' critical lower limb ischaemia patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:CD010747. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010747.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtake T, Mochida Y, Ishioka K, Oka M, Maesato K, Moriya H, et al. Autologous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood CD34 positive cell transplantation for hemodialysis patients with critical limb ischemia: A prospective phase II clinical trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7:774–82. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liotta F, Annunziato F, Castellani S, Boddi M, Alterini B, Castellini G, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of autologous non-mobilized enriched circulating endothelial progenitors in patients with critical limb ischemia- The SCELTA trial. Circ J. 2018;82:1688–98. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Zhang J, Cui W, Fang Y, Li L, Ji S, et al. Composite hydrogel modified by IGF-1C domain improves stem cell therapy for limb ischemia. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:4481–93. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b17533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qadura M, Terenzi DC, Verma S, Al-Omran M, Hess DA. Concise review: Cell therapy for critical limb ischemia: An integrated review of preclinical and clinical studies. Stem Cells. 2018;36:161–71. doi: 10.1002/stem.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parikh PP, Liu ZJ, Velazquez OC. A molecular and clinical review of stem cell therapy in critical limb ischemia. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:3750829. doi: 10.1155/2017/3750829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karantalis V, Schulman IH, Balkan W, Hare JM. Allogeneic cell therapy: A new paradigm in therapeutics. Circ Res. 2015;116:12–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.305495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berndt R, Hummitzsch L, Heß K, Albrecht M, Zitta K, Rusch R, et al. Allogeneic transplantation of programmable cells of monocytic origin (PCMO) improves angiogenesis and tissue recovery in critical limb ischemia (CLI): A translational approach. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:117. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0871-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]