Abstract

Introduction:

Till date, weight-bearing radiographs have been the cornerstone for planning surgeries on flatfoot. The technique, however, has limitations due to the superimposition of the bones and the lack of reproducibility. Weight-bearing CT with its unique design overcomes these limitations and enables cross-sectional imaging of the foot to be done in the natural weight-bearing position. In this paper, we report our initial experience in weight-bearing cross-sectional imaging of the foot for assessment of flatfoot deformity.

Materials and Methods:

Around 19 known cases of flatfoot were scanned on the weight-bearing CT. Each foot was then assessed for the various angles and also for the presence/absence of extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement and subfibular impingement. Other associated abnormalities like secondary osteoarthritic changes, were also noted.

Results:

The Meary, as well as the calcaneal angles, were abnormal, in all but one separate foot. Forefoot abduction was seen in 7 of the 19 feet. The hind foot valgus angle was greater than 10° in all patients. Extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement was seen in 13 of 19 feet. Secondary osteoarthritic changes were seen in 14 feet.

Conclusion:

Weight-bearing CT scan is a very useful technique for evaluation of flatfoot and associated complications. It overcomes the limitations of the radiographs by providing multiplanar three-dimensional assessment of the foot in the natural weight-bearing position and at the same time being easily reproducible and consistent for the measurements around the foot. The definite advantage over the conventional cross-sectional scanners is the weight-bearing capability.

Keywords: Extremity CT, flatfoot, pes planus, weight-bearing CT

Introduction

Flatfoot deformity is a complex foot deformity with various components like medial longitudinal arch collapse, hindfoot valgus, and forefoot abduction.[1] The deformities typically occur in the orthostatic posture[2] due to failure of the various static and dynamic stabilizers of the foot.

Thus, the assessment of these feet in weight-bearing position is a mandate to analyze the biomechanical alterations and plan meticulous correction of the same. Till date, weight-bearing radiographs have been the cornerstone for planning surgeries on flatfoot. It is however always challenging to measure the various angles on the radiographs due to superimposition of the bones. Another, even bigger challenge is the lack of reproducibility[3] of these radiographs and the associated rotational and fan distortions.[4]

Conventional cross-sectional techniques are therefore often needed to complement the information on the radiographs. These conventional cross-sectional techniques, though are reproducible and provide a multiplanar detailed assessment of the joints and bones, have a scanner design limitation of being able to scan only in supine/prone position. Scans cannot be done in the natural weight-bearing position, needed to assess the exact biomechanical alterations in the foot in that position.

A few researchers tried to simulate body weight support on the ankle and foot, passively in the supine position using various strategies.[5] These systems, however, had multiple lacunae including the low reproducibility of these techniques and the nonutilization of the active muscle forces that act during orthostatic physiological positioning.[6,7,8] It was thus realized that these systems did not resolve the limitation of conventional computed tomography (CT).

The weight-bearing cone-beam CT [WBCT], with its unique and compact design, overcomes these limitations and enables cross-sectional imaging of the foot and ankle, to be done in the natural weight-bearing position. This enables meticulous assessment of the dynamics of the foot in the orthostatic position.[9,10,11] The use of weight-bearing CT [WBCT] is thus expected to improve precision and accuracy in characterization of the adult acquired flatfoot [AAFD].[12] The same technique can also be used to assess the knee joint in the weight-bearing position.

Apart from the advantage of multiplanar capabilities, the acknowledged high-resolution images[3,13] and the advantage of obtaining scans in weight-bearing position, these scanners also have the advantage of reduced radiation exposure[3,10,14,15,16] and shorter scan time. Radiation doses for a standard extremity scan with weight bearing CT, ranges from 0.01 to 0.03 mSv per scan.[3,17] The total scan cost with this system is also less or similar to the other available imaging technologies.

The weight-bearing CT scanner uses the technique of the clinically established dental cone-beam scanners.[14] The cone--beam technology enables a smaller and compact gantry size with a wider range of gantry movements, which includes tilting the gantry to the horizontal orientation and lowering it close to floor level, making weight-bearing imaging, with the patient in a standing position possible.[17] In orthopedics, the use of CBCT is rather new and was first published by Zbijewski et al.,[18] in 2011. The first mention of CBCT in orthopedics was in a paper published by Tuominen et al., in 2013.[17]

In this paper, we report our initial experience in weight-bearing cross-sectional imaging of the foot and ankle for assessment of flatfoot deformity.

Materials and Methods

18 patients [15 females and 3 males], aged 13 to 69 years, and known to have flatfeet were scanned on the weight-bearing CT. Only the symptomatic foot was scanned. A total of 19 feet were scanned, which included 7right and 12 left feet.

All scans were done on the CBCT [Carestream, Onsight 3D extremity system]. The scans were done in the standing weight-bearing position, with the foot to be scanned placed inside the gantry and the other leg outside, and bent at the knee to provide adequate weight bearing on the foot being scanned.

The acquired images were then reconstructed in soft tissue and bone algorithms and sent digitally to the workstation [Osirix, IMAC, Apple, Inc, USA] for further assessment.

An MRI was also done for 8 out of 19 feet scanned on the CBCT.

Each foot was then assessed for the lateral talar i.e., the first metatarsal [Meary] angle. The calcaneal pitch was measured in all except one patient, where the heel was not covered. Heel valgus angle was measured. A note was made of presence or absence of forefoot abduction. A specific note was also made for the presence/absence of extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement and subfibular impingement. Other associated abnormalities, which could be a cause of the patient's complaints/symptoms were noted.

The presence of osteoarthritic changes and their distribution pattern were noted. The status of the muscles surrounding the ankle was also assessed on the scan.

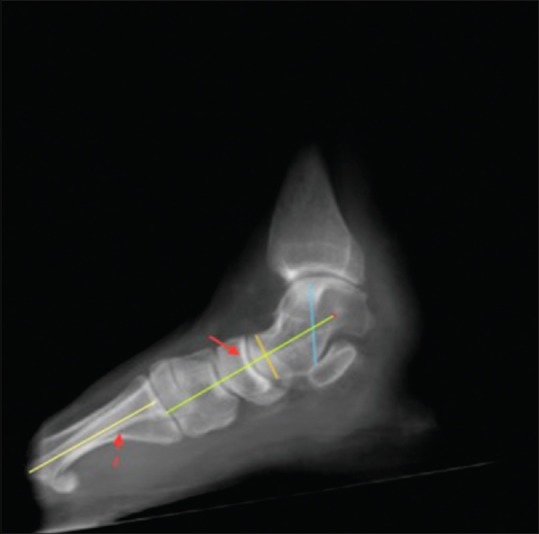

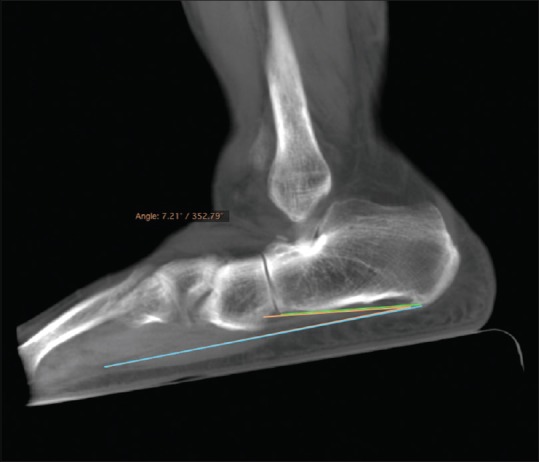

The lateral talar i.e., first metatarsal angle, also known, as the Meary angle is the angle formed between the long axis of the talus and the first metatarsal on a weight-bearing lateral view [Figure 1]. This is one of the most often used measurements for assessing medial longitudinal arch collapse. In a normal foot, the talar axis is in line with the first metatarsal axis. An angle that is greater than 4° convex downward is considered flatfoot.[19,20]

Figure 1.

Sagittal reformatted thick slab CBCT showing normal lateral talar-1st metatarsal angle (The lateral talar axis [solid arrow] is parallel to the 1st metatarsal axis [dashed arrow])

The calcaneal pitch is defined as the angle between the horizontal plane and the line drawn along the plantar-most surface of the calcaneus to the inferior border of its distal articular surface[21,22] [Figure 2]. There have been differing opinions concerning the normal range of calcaneal pitch, some consider 18 to 20° as normal,[22] while few consider 17 to 32° as the normal range.[21]

Figure 2.

Sagittal reformatted thick slab CBCT showing calcaneal pitch (Normal range 18–20°/17–32°)

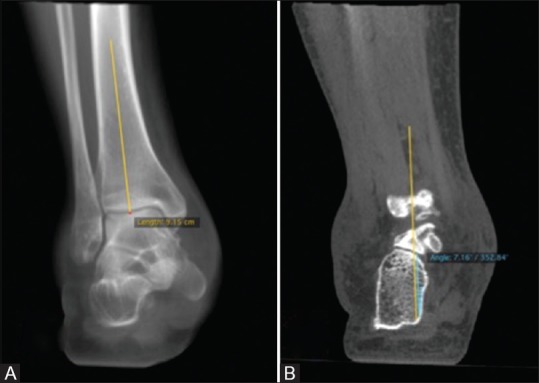

Heel valgus angle was measured as the angle between the medial calcaneal cortex and the long axis of the tibia. This is measured just posterior to the sustentaculum, at the level of the posterior talus and tibia[23] [Figure 3]. The measurement is performed in the most posterior coronal image that includes both the tibia and calcaneus. The normal hindfoot angle is estimated between 2° and 6° of valgus, in the general population.[24]

Figure 3 (A and B).

Coronal reformatted images (A) Tibial axis (B) normal heel valgus angle (between the tibial axis and the medial calcaneal cortex)

Forefoot abduction was assessed on the AP view of the foot and was said to be present when the line drawn through the mid-axis of the talus was seen to be angled medially to the first metatarsal shaft axis[12] [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Axial reformatted thick slab CBCT showing normal AP talar-1st metatarsal angle (The AP talar axis [solid arrow] is parallel to the 1st metatarsal axis [dashed arrow])

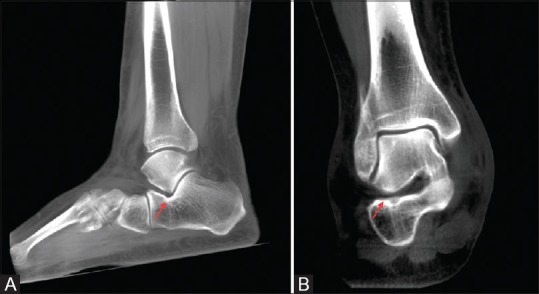

Extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement was said to be present when there was direct contact between the inferior aspect of the lateral talar process and the calcaneum at the calcaneal angle. In advanced stages, sclerosis and cystic changes were also seen in the apposing surfaces.[23,25] In normal individuals, a gap is seen between these bony surfaces even on weight-bearing positions [Figure 5]. A note was also made of the associated presence of subfibular impingement, described as direct contact between the tip of fibula and the lateral calcaneal process, with bony changes in the apposing surfaces. This is said to occur with progression of the talocalcaneal impingement.[23,25]

Figure 5 (A and B).

Normal appearance of the extra-articular talocalcaneal space on weight-bearing scans. Note the normal gap between the apposing bony surfaces on the sagittal (A) as well as coronal (B) reformatted thick slab images (arrows)

Results

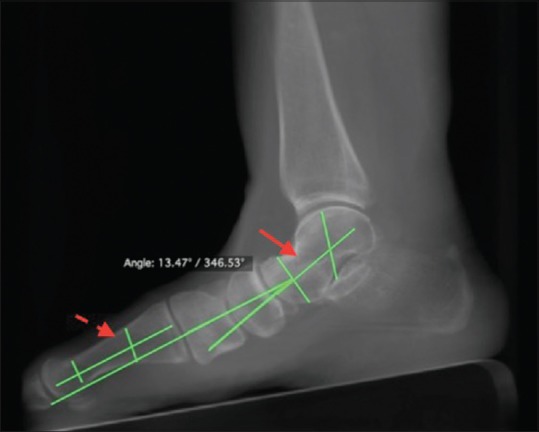

The lateral talar i.e., first metatarsal angle was more than 4° [Figure 6], in all but one foot. In this one foot, however, the calcaneal angle was significantly reduced [Figure 7] and was thus consistent with flatfoot.

Figure 6.

Sagittal reformatted thick slab CBCT showing increased lateral talar-1st metatarsal angle (There is plantarward angulation of lateral talar axis [solid arrow] with respect to the 1st metatarsal axis [dashed arrow], with the angle between them measuring 13.47°)

Figure 7.

Sagittal reformatted thick slab CBCT showing reduced calcaneal pitch

The calcaneal angle was also less than 17° in all but one foot, where also the angle was only borderline increased and measured 17.6°.

Forefoot abduction was seen in 7 of the 19 feet [Figure 8]. Forefoot adduction was seen in only one foot, where the metatarsal axis was angled medially to the AP talar axis, with the angle measuring 29°. The AP talar axis was parallel to the first metatarsal axis in all the remaining 11 feet.

Figure 8.

Axial reformatted CBCT, showing forefoot abduction, with lateral angulation of the 1st metatarsal axis [dashed arrow], with respect to the AP talar axis [solid arrow]

The hindfoot valgus angle was greater than 10° in all feet [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Coronal reformatted images with increased heel valgus angle (between the tibial axis and the medial calcaneal cortex)

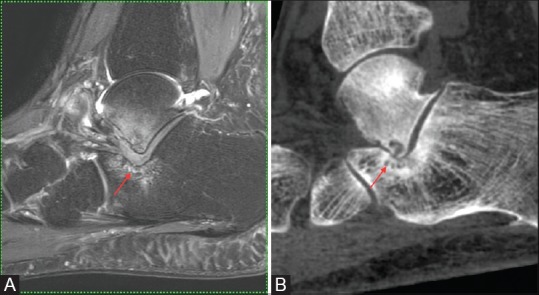

Extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement was seen in 13 of the 19 feet scanned. Among these 13 feet, an MRI was also done in 5 feet and the MRI did not show any contact between the talus and the calcaneum, at the calcaneal angle, in any of the 5 feet. The MRI, however, showed cystic changes with edema and sclerosis of the apposing bony surfaces. There was also edema of the sinus tarsi fat. The direct contact between the bony surfaces was very well appreciated on the WBCT in all of these 5 cases [Figures 10 and 11].

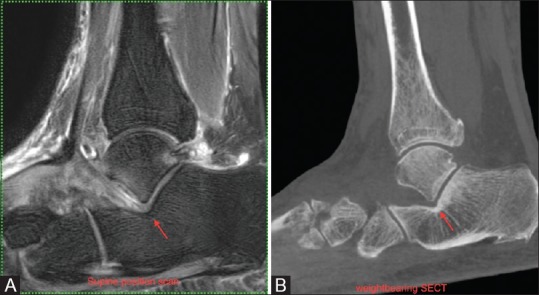

Figure 10 (A and B).

Extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement in patient with flatfoot (A) sagittal MRI in neutral position do not show apposition between the bony surfaces with intervening soft tissue seen on the MRI (arrow), (B) The sagittal reformatted images of the WBCT clearly shows the direct contact between the bony surfaces and associated bony changes as well (arrow)

Figure 11 (A and B).

Extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement in patient with flat foot (A) coronal MR images in neutral position do not show apposition between the bony surfaces with intervening soft tissue seen on the MRI (arrow), (B) coronal reformatted images of the WBCT clearly shows the direct contact between the bony surfaces and associated bony changes as well (arrow)

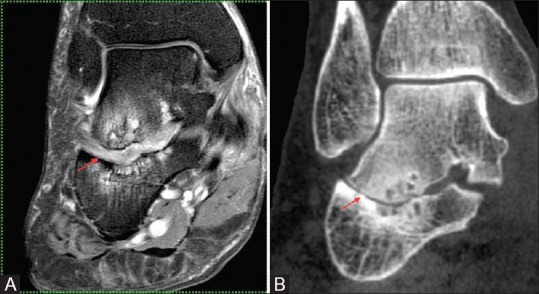

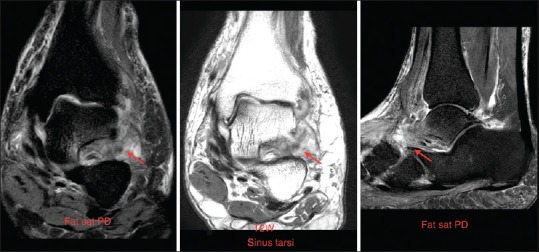

Yet another patient [different from the above mentioned 5 patients], where an MRI was done, also had an MRI appearance quite similar to that seen in the above-described cases of talocalcaneal impingement. This patient had edema of the apposing surfaces of the talus and the calcaneum at the calcaneal angle and edema of the sinus tarsi. There were however no cystic changes or sclerosis in the bones. Interestingly, this patient showed no narrowing of the distance between the bony surfaces or talocalcaneal impingement on the WBCT [Figures 12 and 13]. Thus, in this patient the pattern on MRI was attributed to sinus tarsi syndrome, rather than talocalcaneal impingement. Also this was the only case of pes planus with normal Meary angle but with a severely reduced calcaneal pitch. Mild heel valgus was seen but without any forefoot abduction.

Figure 12.

Sinus tarsi syndrome in patient with the flatfoot: The MRI show ill-defined edematous soft tissue in the sinus tarsi (arrow) with edema of the apposing bony surfaces

Figure 13 (A and B).

Same patient as Figure 12: Sagittal MRI in neutral position (A) do not show apposition between the bony surfaces with intervening edematous soft tissue seen similar to that seen in cases with extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement (arrow), (B) The sagittal reformatted images of the WBCT shows persistence of the distance between the bony surfaces without any collapse or direct contact between the bony surfaces as seen in the cases with extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement

Overt subfibular impingement with direct contact of the apposing fibular and calcaneal surfaces and associated bony changes was seen in only 3 feet [Figure 14].

Figure 14 (A and B).

Subfibular impingement in a patient with flat foot (A) coronal MRI in neutral position show mildly reduced distance between the tip of the lateral malleolus and the lateral calcaneal process. (arrow), (B) coronal reformatted images of the WBCT shows further reduction of the distance with almost apposition of the bony surfaces (arrow)

Osteoarthritic changes were seen involving the intertarsal joints in 14 feet, of which, 10 feet had a predominant talonavicular osteoarthritis. Dorsal talar spurs [Figure 15] were seen in 9 of these 10 patients. Joint effusion and ganglion cyst [Figure 16] was also seen in few patients.

Figure 15 (A and B).

Dorsal spur at a talonavicular joint in patient with flatfoot (A) sagittal reformatted and (B) sagittal reformatted thick slab images of the WBCT, showing a prominent dorsal spur at the talonavicular joint without any evidence of tarsal coalition. (arrows)

Figure 16 (A and B).

Dorsal spur at tibionavicular joint with ganglion cyst in a patient with flatfoot (A) sagittal reformatted WBCT image and (B) sagittal MRI showing a prominent dorsal spur at the talonavicular joint (arrows) with a tuft of ganglion cyst (better appreciated on the MRI) without any evidence tarsal coalition

Isolated atrophy of the abductor digiti mini muscle, often attributed to Baxter neuropathy,[26] was seen in 10 of the 19 patients.

Discussion

Flatfoot, predominantly characterized by medial longitudinal arch collapse, is also closely associated with other mal-alignments about the ankle, like hindfoot valgus, and forefoot abduction. The assessment of the extent of alteration in these relationships is essential for proper surgical planning. Weight-bearing CT scan provides a very close-to-accurate assessment of the relationships of the various bones in the orthostatic position, thus enabling meticulous surgical planning and monitoring on follow-up as well. It enhances our understanding of the complex three-dimensional deformities in the foot, which is rather difficult with the conventional two-dimensional radiographic images.[12,27]

In all the patients scanned, the measurements on the WBCT were consistent with flatfoot. Associated angle deviations consistent with forefoot abduction and heel valgus are also conveniently assessed. The concomitant presence of these abnormalities was clearly seen with forefoot abduction in 7 of 19 flatfeet and heel valgus seen in all patients.

The concomitant presence of and the close association of flatfoot with extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement was also clearly depicted with extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement seen in approximately 70% [13/19] of the feet scanned. The extra edge of weight-bearing CBCT over MRI, in diagnosing this entity was also clearly emphasized by the rather lack of overt impingement seen in the five cases of extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement who also underwent an MRI. WBCT was thus helpful in differentiating extra-articular talocalcaneal impingement from sinus tarsi syndrome, which are close mimics both clinically as well as radiologically.

This was well depicted in one of the cases described above. Moreover, WBCT also helped in picking up the impingement before the development of overt bony changes.

An interesting note was also made of predominant talonavicular osteoarthritis in 10 of 19 cases and of dorsal talar spurs in 9 of 10 cases with talonavicular osteoarthritis. Seven of these 10 patients also had a presenting complain of pain over the dorsal aspect of the talonavicular joint. This could be related to the altered biomechanics of the foot due to the flatfoot deformity leading to unusual stress on the talonavicular joint and resultant changes as described.

An association with selective atrophy of the abductor digiti minimi was also seen with the atrophy of the muscle seen in more than 50% of the feet scanned.

Conclusion

Weight-bearing CT scan is a very useful and reproducible technique for evaluation of flatfoot and associated complications. It is being increasingly used by the foot and ankle surgeons in the western countries for assessment of patients with AAFD.[5,25,28,29,30,31,32,33]

The superiority of this modality over the existing methods of assessing flatfoot is evident by the fact that it not only overcomes the limitations of the radiographs but also those of the conventional cross-sectional scanners. It overcomes the limitations of the radiographs by providing multiplanar three-dimensional assessment of the foot in the natural weight-bearing position. It is at the same time easily reproducible and more accurate and consistent for the measurements around the foot. The definite advantage over the conventional cross-sectional scanners is the weight-bearing capability.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Peeters K, Schreuer J, Burg F, Behets C, Van Bouwel S, Dereymaeker G, et al. Alterated talar and navicular bone morphology is associated with pes planus deformity: A CT-scan study. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:282–7. doi: 10.1002/jor.22225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toullec E. Adult flatfoot. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res OTSR. 2015;101(Suppl 1):S11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godoy-Santos AL, Cesar Netto C Weight-Bearing Computed Tomography International Study Group. Weight-bearing computed tomography of the foot and ankle: An update and future directions. Acta Ortop Bras [online] 2018;26:135–9. doi: 10.1590/1413-785220182602188482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lintz F, Cesar Netto C Weight Bearing CT International Study Group. Weight-bearing cone beam CT scans in the foot and ankle. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3:278–86. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferri M, Scharfenberger AV, Goplen G, Daniels TR, Pearce D. Weightbearing CT scan of severe flexible pes planus deformities. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:199–204. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Bergeyk AB, Younger A, Carson B. CT analysis of hindfoot alignment in chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:37–42. doi: 10.1177/107110070202300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshioka N, Ikoma K, Kido M, Imai K, Maki M, Arai Y, et al. Weight-bearing three-dimensional computed tomography analysis of the forefoot in patients with flatfoot deformity. J Orthop Sci. 2016;21:154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Xu J, Wang X, Huang J, Zhang C, Chen L, et al. An in vivo study of hindfoot 3D kinetics in stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) flatfoot based on weight-bearing CT scan. Bone Joint Res. 2013;2:255–63. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.212.2000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burssens A, Peeters J, Buedts K, Victor J, Vandeputte G. Measuring hindfoot alignment in weight bearing CT: A novel clinical relevant measurement method. Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;22:233–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrino JA, Al Muhit A, Zbijewski W, Thawait GK, Stayman JW, Packard N, et al. Dedicated cone-beam CT system for extremity imaging. Radiology. 2014;270:816–24. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Cesar Netto C, Schon LC, Thawait GK, da Fonseca LF, Chinanuvathana A, Zbijewski WB, et al. Flexible adult acquired flatfoot deformity: Comparison between weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing measurements using conebeam computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:e98. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.01366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Cesar Netto, Shakoor D, Dein EJ, Zhang H, Thawait GK, Richter M, et al. Influence of investigator experience on reliability of adult acquired flatfoot deformity measurements using weightbearing computed tomography? Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2018.03.001. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2018.03.001. Epub 2018 Mar 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demehri S, Muhit A, Zbijewski W, Stayman JW, Yorkston J, Packard N, et al. Assessment of image quality in soft tissue and bone visualization tasks for a dedicated extremity cone-beam CT system. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1742–51. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3546-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R, Cheung AC, Bartling SH, Lisauskas J, Grasruck M, Leidecker C, et al. Flatpanel volume CT: Fundamental principles, technology, and applications. Radiographics. 2008;28:2009–22. doi: 10.1148/rg.287085004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas D, Bible JE, Bohan M, Simpson AK, Whang PG, Grauer JN. Radiation exposure from musculoskeletal computerized tomographic scans. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1882–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulze D, Heiland M, Thurmann H, Adam G. Radiation exposure during midfacial imaging using 4- and 16-slice computed tomography, cone beam computed tomography systems and conventional radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:83–6. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/28403350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuominen EK, Kankare J, Koskinen SK, Mattila KT. Weight-bearing CT imaging of the lower extremity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:146–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zbijewski W, De Jean P, Prakash P, Ding Y, Stayman JW, Packard N, et al. A dedicated cone-beam CT system for musculoskeletal extremities imaging: Design, optimization, and initial performance characterization. Med Phys. 2011;38:4700–13. doi: 10.1118/1.3611039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chi TD, Toolan BC, Sangeorzan BJ, Hansen ST., Jr The lateral column lengthening and medial column stabilization procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999:81–90. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199908000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedowitz WJ, Kovatis P. Flatfoot in the Adult. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:293–302. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiGiovanni JE, Smith SD. Normal biomechanics of the adult rearfoot: A radiographic analysis. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1976;66:812–24. doi: 10.7547/87507315-66-11-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaschak TJ, Laine W. Surgical radiology. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1988;5:797–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donovan A, Rosenberg ZS. Extra-articular lateral hindfoot impingement with posterior tibial tendon tear: MRI correlation. Am J Radiol. 2009;193:672–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burssens A, Van Herzele E, Leenders T, Clockaerts S, Buedts K, Vandeputte G, et al. Weightbearing CT in normal hindfoot alignment-Presence of a constitutional valgus? Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;24:213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malicky ES, Crary JL, Houghton MJ, Agel J, Hansen ST, Jr, Sangeorzan BJ. Talocalcaneal and subfibular impingement in symptomatic flatfoot in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:2005–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Recht MP, Grooff P, Ilaslan H, Recht HS, Sferra J, Donley BG. Selective atrophy of the abductor digiti quinti: An MRI study. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:W123–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschmann A, Pfirrmann CW, Klammer G, Espinosa N, Buck FM. Upright cone CT of the hindfoot: Comparison of the non-weight-bearing with the upright weight-bearing position. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:553–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-3028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kido M, Ikoma K, Imai K, Maki M, Takatori R, Tokunaga D, et al. Load response of the tarsal bones in patients with flatfoot deformity: In vivo 3D study. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32:1017–22. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis SJ, Deyer T, Williams BR, Yu JC, Lehto S, Maderazo A, et al. Assessment of lateral hindfoot pain in acquired flatfoot deformity using weightbearing multiplanar imaging. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31:361–71. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apostle KL, Coleman NW, Sangeorzan BJ. Subtalar joint axis in patients with symptomatic peritalar subluxation compared to normal controls. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35:1153–8. doi: 10.1177/1071100714546549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colin F, Horn Lang T, Zwicky L, Hintermann B, Knupp M. Subtalar joint configuration on weightbearing CT scan. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35:1057–62. doi: 10.1177/1071100714540890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krahenbuhl N, Tschuck M, Bolliger L, Hintermann B, Knupp M. Orientation of the subtalar joint: Measurement and reliability using weightbearing CT scans. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:109–14. doi: 10.1177/1071100715600823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Probasco W, Haleem AM, Yu J, Sangeorzan BJ, Deland JT, Ellis SJ. Assessment of coronal plane subtalar joint alignment in peritalar subluxation via weight-bearing multiplanar imaging. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:302–9. doi: 10.1177/1071100714557861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]