Abstract

Objective: To assess the diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) of photodynamic diagnosis with 5-aminolaevulinic acid (5-ALA), hexylaminolevulinate (HAL) and narrow band imaging (NBI) for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), with white light-guided cystoscopy (WLC) as reference standard.

Materials and Methods: A systematic review and narrative synthesis was performed in accordance with PRISMA. Major electronic databases were searched until 20th May 2019. All studies assessing the DTA of 5-ALA, HAL and NBI compared with WLC at patient and lesion-level were included. Relevant sensitivity analyses and risk of bias (RoB) assessment were undertaken.

Results: 26 studies recruiting 3979 patients were eligible for inclusion. For patient-level analysis, NBI appeared to be the best (median sensitivity (SSY) 100%, median specificity (SPY) 68.45%, median positive predictive value (PPV) 90.75%, median negative predictive value (NPV) 100% and median false positive rate (FPR) 31.55%), showing better DTA outcomes than either HAL or 5-ALA. For lesion-level analysis, median SSY across NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 93.08% (IQR 87.04-98.81%), 93.16% (IQR 91.48-97.04%) and 94.42% (IQR 82.37-95.73%) respectively. As for FPR, median values for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 20.40% (IQR 13.68-27.36%), 17.43% (IQR 12.79-22.40%) and 28.12% (IQR 22.08-42.39%), respectively. Sensitivity analyses based on studies with low to moderate RoB and studies with n>100 patients show similar findings.

Conclusions: NBI appears to outperform 5-ALA and HAL in terms of diagnostic accuracy. All three modalities present high FPR, hence indicating the ability to detect additional cases and lesions beyond WLC.

Keywords: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, diagnostic accuracy, narrow band imaging, photodynamic diagnosis, white light-guided cystoscopy

Introduction

Bladder cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed tumor types, with an estimated 166,583 newly diagnosed cases and 58,742 deaths due to the disease in Europe in 2012, about 75% among which present as non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) 1-4. Most patients with NMIBC develop a recurrence (up to 70%) within 5 years after initial treatment 5-7. Traditional white light (WL) guided transurethral resection of bladder tumors (TURBT) has been regarded as the gold standard method for diagnosis and treatment. However, the accuracy of white light cystoscopy (WLC) in detecting disease is unsatisfactory, which leads to residual untreated disease or missed coexisting carcinoma in situ (CIS), mainly due to overlooked lesions. Recurrence after TURBT is remarkably common with up to 30% of patients having tumor identified at the first-check cystoscopy at 3 months and 50% of patients developing a recurrence within the first year 8, 9. Thus, new imaging technologies are being developed to improve visualization of tumors, which can assist urologists in achieving complete resection and reducing the risk of recurrence.

Photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) is applied with intravesical instillation of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or hexaminolevulinic acid (HAL) under blue-violet (380-440nm) light. The effect of 5-ALA on tumor detection in the urinary bladder has been confirmed in several clinical trials 10-12. 5-ALA guided cystoscopy has been shown to be an efficient method of mapping the entire mucosa to detect urothelial tumors and flat CIS lesions13. HAL is the lipophilic hexylester of 5-ALA and has been commercially available since 2006, which is considered an efficient diagnostic tool in the detection of NMIBC. However, recent prospective, randomized studies have challenged the benefits of PDD14.

Narrow band imaging (NBI) is an image-processing modality filtering WLC to two narrow band widths of 415 and 540 nm, which corresponds to the visible blue and green light spectra, respectively. In contrast to PDD, NBI does not require fluorescent agents to improve the visualization of vascularized mucosal lesions, such as NMIBC. The utility of NBI for increasing tumor detection compared with WLC has been confirmed in several initial trials 15-17. Though early results are encouraging, there is currently limited experience with NBI in detecting bladder cancer. NBI may also result in increased false-positives, especially for patients with prior intravesical instillations 18, 19. The specific objective of our study was to perform a systematic review assessing the diagnostic accuracy of PDD using 5-ALA, HAL, and NBI against the reference standard of WLC for NMIBC.

Materials and Methods

Literature-search strategy

The review was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA)20 and Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD)21. Databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, PMC, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, Central Register of Controlled Trials and Embase were systematically searched from inception up to 13th May 2019, using the following MeSH and combined terms which were adjusted for the different databases: “photodynamic diagnosis, PDD, hexaminolevulinate, HAL, 5-aminolevulinate acid, 5-ALA, narrow band imaging, NBI, white light cystoscopy, bladder cancer, bladder tumor and BCa.” The search was supplemented by additional sources including the reference lists of all included studies. Only full text articles published in the English language were included. At least two reviewers (CC and HL) screened all abstracts and full-text articles independently. Disagreement was resolved by discussion or by reference to an independent arbiter (JH). Exclusion criteria were animal studies, reviews, historical overviews, or editorials. For missing or unclear data, we contacted the authors to get more information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All prospective and retrospective studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) with 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), hexaminolevulinate (HAL), or narrow band imaging (NBI), with WLC as reference standard, were included. Additional inclusion criteria included the following elements: 1) Population: Patients aged ≥18 years with suspected NMIBC in the primary setting (i.e. primary diagnosis), or patients with previously confirmed NMIBC undergoing surveillance (i.e. diagnosis of recurrent tumours). Previous intravesical chemotherapy instillation was not described. NMIBC included Ta, T1 and CIS; 2) Reference standard: All patients must have had WLC as the reference standard, with positive or negative cases being denoted by the presence or absence of NMIBC confirmed by histopathological examination; 3) Diagnostic performance should be compared in intra-patient groups. 4) Outcomes: The primary outcomes were sensitivity (SSY), specificity (SPY), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), false positive rate (FPR), and false negative rate (FNR). If the outcomes were not reported in the study, these were derived and calculated from the available data based on the construction of 2x2 tables.

We limited these criteria to studies published in the English language and to original studies only. When two or more studies reported on a group of patients at the same institution during an overlapping time period, only the article with the latest data set was included, unless different outcomes were reported or different subgroup analyses were performed.

Data Extraction

Data from included studies were extracted by two independent authors (YZ and CC). A data extraction form was developed to collect information, including the first author, study characteristics (country, study design, number of patients, study end points, follow-up), intervention characteristics (index tests, reference standard, duration of follow-up, schedule and nature of WLC), patient characteristics (age, sex, NMIBC patients, biopsy lesions, tumor lesions, disease grade and stage, disease setting), and diagnostic accuracy measure as previously specified. Any unresolved discrepancies were resolved by consensus or referred to an adjudicating senior author (JH).

Quality assessment strategy

The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) 22 was performed on included studies. The risk of bias (RoB) was scored as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear” for each domain to designate a low, high, or unclear RoB, respectively. The scoring was performed independently by two authors (YZ and CC); disagreement was resolved by discussion or with an independent arbiter (JH). We arbitrarily defined “low RoB” as at least 3 domains scoring “low” across both categories without any domains scoring “high” across either category; “moderate RoB” as at least 2 domains scoring “low” across both categories and without any domain scoring “high” across either category; all other scoring patterns were defined as “high” RoB.

Statistical analysis

Data was extracted from each study at lesion or patient level to assess 5-ALA, HAL and NBI as the index test using WLC as reference standard, with positive or negative disease as determined by histopathological examination. 2×2 tables were used to summarize the above data. These tables were used to calculate the primary outcomes of SSY, SPY, NPV, PPV, FPR and FNR. Studies reporting insufficient data were excluded. SSY was defined as the proportion of index test-positive patients or lesions out of all cases of WLC-positive findings. SPY referred to the proportion of index test-negative patients or lesions out of all cases of WLC-negative findings. NPV was defined as the proportion of true negatives (i.e. negative index test and negative WLC) out of all index test-negative cases or lesions; PPV was defined as the proportion of true positives (i.e. positive index test and positive WLC) out of all index test-positive cases or lesions. FNR was defined as the proportion of index test-negative cases or lesions out of all cases of WLC-positive findings; FPR was defined as the proportion of index test-positive cases or lesions out of all cases of WLC-negative findings. FPR provides measurement of additional diagnostic value of PDD or NBI over WLC, as FP cases or lesions referred to patients who had index test-positive findings whilst WLC found negative findings. Because of the expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies, only a narrative synthesis was performed. All diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) outcomes were presented as proportions (%) for individual studies and summarized as median and interquartile range (IQR) for all studies collectively. The pooled estimates for Hierarchical Summary Receiver Operating Curve (HSROC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the compared end points were used, which is an overall summary measure index of the diagnostic accuracy. A perfect test will have an Area Under Curve (AUC) close to 1 and a poor test has AUC close to 0.5. Results were plotted on HSROC using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). To explore the effect of heterogeneity on the results, sensitivity analyses were planned based on patient-level vs lesion-level analysis, disease grade (low grade vs high grade), stage (pTa vs pT1), setting (primary vs recurrent tumours), number of participants (studies with n>100 patients only), and on studies with low to moderate RoB.

Results

Quantity of evidence identified

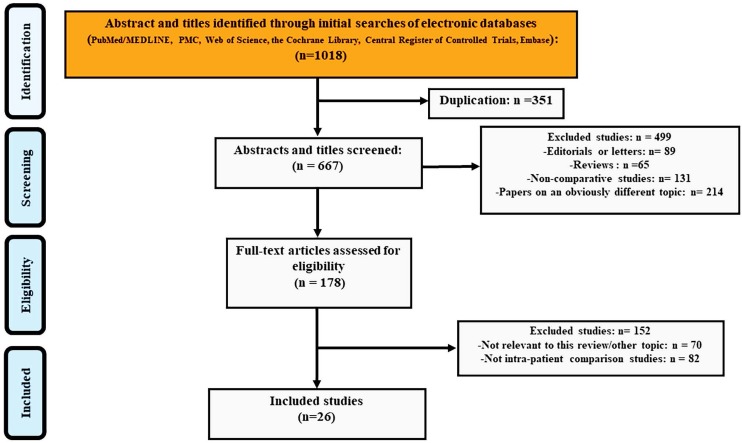

Figure 1 showed the number of citations retrieved and the selection flow diagram for the studies included in the analysis. The search yielded 1018 entries and 351 of these were duplicates. We excluded 499 studies when screening titles and abstracts: 89 editorials or letters, 65 reviews or meeting abstracts, 131 non-comparative studies and 214 papers on an obviously different topic. During the screening of 178 full-text articles, 70 studies were excluded for not being relevant to this review and another 82 studies were excluded for not having within-patient comparisons. Finally, 26 studies17, 23-47 were included in the DTA analysis.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow chart of included studies in DTA analysis.

Characteristics of the included studies

Table 1 summarized the baseline characteristics of the included studies. The 26 included studies enrolled 3979 BC patients (Table 1). The interventions were 5-ALA-based PDD in 9 studies, HAL-based PDD in 8 studies, and NBI in 9 studies. The studies were published from 1994 to 2016, and the sample size ranged from 12 to 605 participants, with a median sample size of 95.5. The mean or median age in the studies was quite similar. Likewise, the male/female ratio showed no differences. Most enrolled patients in included studies were NMIBC (90-100%), while only a few studies described the number of patients according to disease setting (i.e. primary vs recurrent tumors) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Country (No. of institutions) |

No. of patients | Index test | Time period | Age, mean (range) | Male gender (%) | Biopsy lesions (n) | Tumor lesions (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBI vs WLC | ||||||||

| Shadpour et al.201628 | Unicentre, Iran | 50 | NBI | 2012-2013 | 63.86 ± 10.05 | 34(68.0) | NR | 95 |

| Song et al.201626 | Unicentre, Korea | 63 | NBI | 2012-2013 | 66(56-76) | 39(61.9) | 66 | 21 |

| Kobotake et al.201534 | Unicentre, Japan | 135 | NBI | 2010-2014 | 75 | 110(81.5) | 383 | 120 |

| Ye et al.201517 | Multicentre (8), China | 384 | NBI | NR | 61(21-79) | 267(69.5) | 300 | 167 |

| Shen et al.201227 | Unicentre, China | 78 | NBI | 2009-2010 | 68 (33-75) | 62(79.5) | 309 | 211 |

| Zhu et al. 201223 | Unicentre, China | 12 | NBI | 2009-2010 | 57(28-73) | 9(75.0) | 31 | 9 |

| Tatsugami et al.201025 | Unicentre, Japan | 104 | NBI | 2007-2009 | 70.6(38-90) | 88(84.6) | 313 | 110 |

| Cauberg et al.200946 | Multicentre (2), The Netherlands; Czech Republic | 95 | NBI | 2007-2009 | 70.6(38.1-90.2) | 70(73.7) | 389 | 226 |

| Herr et al.200837 | Unicentre, USA | 427 | NBI | 2007 | 65 (26-90) | 316(74.0) | NR | NR |

| HAL vs WLC | ||||||||

| Palou et al.201432 | Multicentre (8), Spain | 283 | HAL | 2008-2009 | 67.5(42-95) | 242(85.5) | 1569 | 621 |

| Lapini et al.201233 | Multicentre (5), Italy | 96 | HAL | 2010-2011 | NR | 80(83.3) | 234 | 108 |

| Burgues et al.201155 | Multicentre (7), Spain | 305 | HAL | 2006-2009 | 66.9(39-93) | 270(88.5) | 1659 | 600 |

| Ray et al.201031 | Unicentre, Uk | 27 | HAL | 2005-2006 | 70(49-82) | 21(77.8) | 120 | NR |

| Schmidbauer et al.200929 | Unicentre, Austria | 66 | HAL | NR | 63(38-84) | 49(74.2) | 364 | NR |

| Geavlete et al.200839 | Unicentre, Romania | 128 | HAL | 2007-2008 | 65(36-81) | NR | NR | NR |

| Fradet et al.200640 | Multicentre (18), USA, Canada And Europe | 298 | HAL | NR | 67±11 | 223(74.8) | NR | 113 |

| Jichlinski et al.200335 | Multicentre (4), Swiss, Germany | 52 | HAL | 2000-2001 | 72±12 | 38(73.1) | NR | 143 |

| 5-ALA vs WLC | ||||||||

| Grimbergen et al.200310 | Unicentre, Netherlands | 160 | 5-ALA | 1998-2002 | 67(30-91) | NR | 917 | 390 |

| Filbeck et al.200242 | Unicentre, Germany | 279 | 5-ALA | 1997-2000 | 34-89 | NR | 636 | 336 |

| Dominicis et al.200144 | Unicentre, Italy | 49 | 5-ALA | NR | 60(31-77) | 42(85.7) | 179 | 52 |

| Ehsan et al.200143 | Unicentre, Germany | 30 | 5-ALA | NR | 55-89 | 19(63.3) | 151 | NR |

| Jeon et al.200136 | Unicentre, Korea | 62 | 5-ALA | 1997-1999 | 61.9(32-80) | 57(91.1) | 274 | 148 |

| Zaak et al.200124 | Unicentre, Germany | 605 | 5-ALA | NR | 65.6(16-99) | 472(78.0) | 2475 | 552 |

| Filbeck et al.199941 | Unicentre, Germany | 123 | 5-ALA | 1997 | 64.5(28-86) | NR | 347 | 124 |

| Riedl et al.199930 | Unicentre, Austria | 52 | 5-ALA | NR | 44-79 | NR | 53 | 123 |

| D'hallewin et al.199845 | Unicentre, Belgium | 16 | 5-ALA | NR | NR | NR | 113 | 50 |

WLC: white light cystoscopy; NT: new technology; 5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexylaminolevulinate; NBI: narrow band imaging; NR: not reported.

Table 2.

Summary of variables of the included studies for sensitivity analysis.

| Study | NMIBC (%) | Primary (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NBI vs WLC | ||

| Shadpour et al.201628 | 100 | NR |

| Song et al.201626 | 94.1 | 63.0 |

| Kobotake et al.201534 | 100 | 42.3 |

| Ye et al.201517 | 100 | 70.3 |

| Shen et al.201227 | 100 | NR |

| Zhu et al. 201223 | 100 | 42.0 |

| Tatsugami et al.201025 | NR | NR |

| Cauberg et al.200946 | NR | 35.9 |

| Herr et al.200837 | 100 | 0 |

| HAL vs WLC | ||

| Palou et al.201432 | 94.1 | 67.1 |

| Lapini et al.201233 | NR | 36.5 |

| Burgues et al.201155 | 100 | NR |

| Ray et al.201031 | 100 | 0 |

| Schmidbauer et al.200929 | 93.1 | NR |

| Geavlete et al.200839 | 92.2 | NR |

| Fradet et al.200640 | 100 | 32 |

| Jichlinski et al.200335 | 100 | NR |

| 5-ALA vs WLC | ||

| Grimbergen et al.200310 | 90.0% | 0 |

| Filbeck et al.200242 | 90.3% | NR |

| Dominicis et al.200144 | 100 | 34.7 |

| Ehsan et al.200143 | NR | NR |

| Jeon at al.200136 | NR | NR |

| Zaak et al.200124 | NR | NR |

| Filbeck et al.199941 | 91.9 | NR |

| Riedl et al.199930 | 100 | NR |

| D'hallewin et al.199845 | 100 | NR |

NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; WLC: white light cystoscopy; 5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexylaminolevulinate; NBI: narrow band imaging; NR: not reported.

Diagnostic test accuracy results

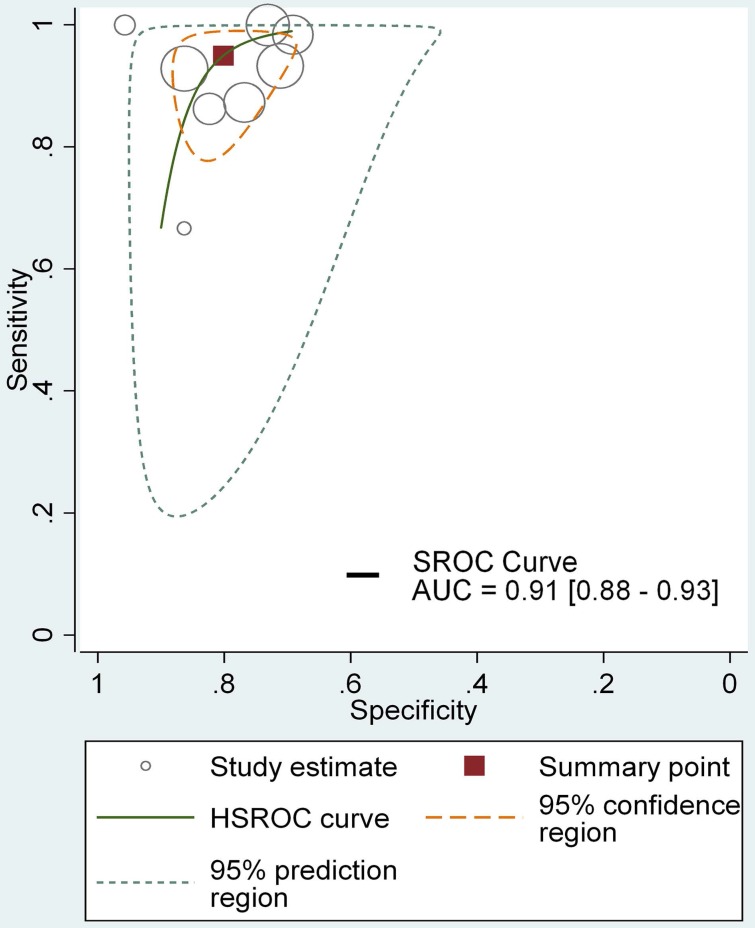

Table 3 showed the results of individual studies included in the DTA analysis. All studies used non-standardized definitions to calculate their DTA outcomes, in which case the results were recalculated using standard definitions with the raw data provided (Table 3). DTA results are presented for all included studies based on patient-level and lesion-level analyses. In the patient-level analysis, the median sensitivity for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 100% (IQR 100-100%), 100% (IQR 91.67-100%) and 100% (IQR 89.67-100%), respectively. NBI appeared to be marginally the best with slightly higher quartile values. Median specificity for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 68.45% (IQR 39.57-96.47%), 41.18% (IQR 33.09- 66.97%), 58.91% (IQR 57.23-75.04%) respectively, with NBI presenting a higher specificity. NBI also showed highest values for PPV (90.75%, IQR 82-95.59%) and NPV (100%, IQR 100-100%). The median FNRs for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 0 (IQR 0-0), 8.33% (IQR 4.17-12.5%) and 0 (IQR 0-10.33%) respectively, with NBI appearing to be the best with the lowest FNR. The median false positive rate for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 31.55% (IQR 3.54-60.08%), 58.82% (IQR 33.03- 66.91%) and 41.09% (IQR 24.96-42.77%) (Table 4) respectively, showing the ability to detect additional cases beyond WLC. Moreover, The HSROC for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were showed in Figure 3, supplementary figure 1 and supplementary figure 2, the AUC of NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 0.91 (95% CI, 0.88- 0.93), 0.94 (95% CI, 0.92-0.96) and 0.82 (95% CI, 0.79- 0.85), presenting excellent diagnostic performance compared with WLC. In this regard, HAL-based PDD appeared to provide the greatest value in detecting additional cases. However, overall, NBI showed better diagnostic accuracy outcomes than HAL or 5-ALA, with greater sensitivity, PPV and NPV.

Table 3.

Results of DTA analysis for all included studies

| Study ID | Patient-level analysis | Lesion-level analysis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt No. | SSY | SPY | FPR | FNR | PPV | NPV | Ln No. | SSY | SPY | FPR | FNR | PPV | NPV | ||

| NBI vs WLC | |||||||||||||||

| Shadpour et al.2016 28 | 50 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 175 | 69/80 | 70/85 | 15/85 | 11/80 | 69/84 | 74/75 | |

| Song et al.201626 | 63 | 16/16 | 46/47 | 1/47 | 0/16 | 16/17 | 23/23 | 66 | 19/19 | 45/47 | 2/47 | 0/19 | 19/21 | 7/7 | |

| Kobotake et al.2015 34 | 135 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 379 | 78/84 | 227/263 | 36/263 | 6/84 | 78/114 | 203/203 | |

| Ye et al.201517 | 103 | 56/56 | 16/45 | 29/46 | 0/56 | 56/85 | 8/8 | 300 | 124/126 | 92/133 | 41/133 | 2/126 | 124/165 | 83/85 | |

| Shen et al.201227 | 78 | 47/47 | 9/22 | 13/22 | 0/47 | 47/47 | 7/7 | 309 | 160/160 | 98/134 | 36/134 | 0/160 | 160/196 | 72/72 | |

| Zhu et al. 201223 | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 31 | 4/6 | 19/22 | 3/22 | 2/6 | 4/7 | 20/20 | |

| Tatsugami et al. 2010 25 | 104 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 313 | 55/63 | 156/203 | 47/203 | 8/63 | 55/102 | 144/144 | |

| Cauberg et al.200946 | 95 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 389 | 167/179 | 116/163 | 47/163 | 12/179 | 167/214 | 47/51 | |

| Herr et al.200837 | 427 | 90/90 | 311/324 | 13/324 | 0/90 | 90/103 | 265/265 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| HAL vs WLC | |||||||||||||||

| Palou et al.201432 | 283 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1492 | 379/416 | 820/948 | 128/948 | 37/416 | 379/507 | 699/702 | |

| Lapini et al.201233 | 96 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 234 | 82/83 | 101/126 | 25/126 | 1/83 | 82/107 | 80/81 | |

| Burgues et al.2011 55 | 305 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1659 | 404/441 | 900/1059 | 159/1059 | 7/441 | 404/563 | 863/863 | |

| Ray et al.201031 | 27 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 120 | 21/21 | 84/94 | 10/94 | 0/21 | 21/31 | 35/35 | |

| Schmidbauer et al.200929 | 66 | 52/52 | 2/8 | 6/8 | 0/52 | 52/58 | 3/3 | 364 | 109/113 | 151/201 | 50/201 | 4/113 | 109/159 | 158/158 | |

| Geavlete et al.2008 39 | 128 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 243 | 87/93 | 56/103 | 47/103 | 6/93 | 87/134 | 76/82 | |

| Fradet et al.200640 | 196 | 40/48 | 128/138 | 10/138 | 8/48 | 40/50 | 106/113 | 206 | 77/83 | 101/112 | 11/112 | 6/83 | 77/88 | 63/71 | |

| Jichlinski et al.200335 | 52 | 33/33 | 7/17 | 10/17 | 0/33 | 33/43 | 3/3 | 143 | 205/254 | 269/343 | 74/343 | 49/254 | 205/279 | 306/314 | |

| 5-ALA vs WLC | |||||||||||||||

| Grimbergen et al.2003 10 | 160 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 889 | 232/244 | 409/527 | 118/527 | 12/244 | 232/350 | 248/257 | |

| Filbeck et al.2002 42 | 279 | 168/168 | 93/102 | 9/102 | 0/168 | 168/177 | 81/81 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Dominicis et al.2001 44 | 49 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 179 | 2/9 | 84/127 | 43/127 | 7/9 | 2/45 | 80/80 | |

| Ehsan et al.200143 | 30 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 151 | 39/40 | 71/91 | 20/91 | 1/40 | 39/59 | 59/59 | |

| Jeon at al.200136 | 62 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 257 | 71/74 | 69/126 | 57/126 | 3/74 | 71/128 | 54/54 | |

| Zaak et al.200124 | 605 | 288/363 | 271/460 | 189/460 | 75/363 | 288/477 | 55/108 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Filbeck et al.1999 41 | 123 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 341 | 75/80 | 185/223 | 38/223 | 5/80 | 75/113 | 78/78 | |

| Riedl et al.199930 | 52 | 26/26 | 10/18 | 8/18 | 0/26 | 26/34 | 6/6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| D'Hallewin et al. 1998 45 | 16 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 113 | 11/14 | 27/63 | 36/63 | 3/14 | 11/47 | 34/34 | |

NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; Pt: patients; Ln: lesions; WLC: white light cystoscopy; 5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexylaminolevulinate; NBI: narrow band imaging; NT: new technology; SSY: sensitivity; SPY: specificity; FPR: false positive rate; FNR: false negative rate; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; NR: not reported.

Table 4.

Summary of results of DTA analysis for index tests

| Study ID | Patient-level analysis | Lesion-level analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | ||

| NBI vs WLC (n=4) | NBI vs WLC (n=8) | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93.08 | 87.04 | 98.81 | |

| Specificity | 68.45 | 39.57 | 96.47 | 79.60 | 72.64 | 86.32 | |

| Positive predictive value | 90.75 | 82 | 95.59 | 76.59 | 65.60 | 81.76 | |

| Negative predictive value | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.41 | 100 | |

| False positive rate | 31.55 | 3.54 | 60.08 | 20.40 | 13.68 | 27.36 | |

| False negative rate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.92 | 1.19 | 12.96 | |

| HAL vs WLC (n=3) | HAL vs WLC (n=8) | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 100 | 91.67 | 100 | 93.16 | 91.48 | 97.04 | |

| Specificity | 41.18 | 33.09 | 66.97 | 82.57 | 77.60 | 87.21 | |

| Positive predictive value | 80.00 | 78.37 | 84.83 | 72.62 | 68.35 | 75.22 | |

| Negative predictive value | 100 | 96.90 | 100 | 99.17 | 96.26 | 100 | |

| False positive rate | 58.82 | 33.03 | 66.91 | 17.43 | 12.79 | 22.40 | |

| False negative rate | 8.33 | 4.17 | 12.50 | 5 | 1.49 | 7.65 | |

| 5-ALA vs WLC (n=3) | 5-ALA vs WLC (n=6) | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 100 | 89.67 | 100 | 94.42 | 82.37 | 95.73 | |

| Specificity | 58.91 | 57.23 | 75.04 | 71.88 | 57.61 | 77.92 | |

| Positive predictive value | 76.47 | 68.42 | 85.69 | 60.79 | 31.42 | 66.24 | |

| Negative predictive value | 100 | 75.46 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| False positive rate | 41.09 | 24.96 | 42.77 | 28.12 | 22.08 | 42.39 | |

| False negative rate | 0 | 0 | 10.33 | 5.58 | 4.27 | 17.63 | |

NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; WLC: white light cystoscopy; 5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexylaminolevulinate; NBI: narrow band imaging; NR: not reported.

Figure 3.

The HSROC curve for NBI diagnosing NMIBC comparing with WLC in lesion level.

Moreover, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy outcomes of NBI, HAL and 5-ALA based on lesion-level analyses, which was showed in Table 4, assessing the diagnostic efficacy of NBI, HAL and 5-ALA on suspicious lesions. The median sensitivity for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 93.08% (IQR 87.04-98.81%), 93.16% (IQR 91.48-97.04%) and 94.42% (IQR 82.37-95.73%) respectively, with these methods showing similar outcomes. Median specificity for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 79.60% (IQR 72.64- 86.32%), 82.57% (IQR 77.60-87.21%), 71.88% (IQR 57.61-77.92%) respectively, with HAL having a highest value; NBI showed the highest PPV (76.59%, IQR 65.60-81.76%) and 5-ALA the highest NPV (100%, IQR 100-100%). The median FNRs for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 6.92% (IQR 1.19-12.96), 5% (IQR 1.49-7.65%) and 5.58% (IQR 4.27-17.63%) respectively. HAL appeared to be best with the lowest FNR. The false positive rates for NBI, HAL and 5-ALA were 20.40% (IQR 13.68-27.36%), 17.43% (IQR 12.79-22.40%) and 28.12% (IQR 22.08-42.39%) respectively. NBI, HAL and 5-ALA appeared to be efficient diagnostic methods for lesion detection.

Sensitivity analysis

WLC was used as standard reference in all the included studies. WLC protocol was similar among included studies and applied on suspicious lesions. SSY and FPR could provide a measure of diagnostic value of PDD or NBI over WLC. When we excluded studies with high RoBs, it showed that NBI had a higher sensitivity (95.85%, IQR 88.80-99.60%) and FPR (25.01%, IQR 19.02-28.34%) than HAL or 5-ALA at lesion-level (Table 5, Supplementary Table 1-3). For studies with low to moderate RoB at patient level (Table 5), 5 studies (i.e. 1 study for 5-ALA, 1 study for HAL and 3 studies for NBI) were included. The analysis showed that NBI had a higher sensitivity (100%) and FPR (59.09%) than HAL or 5-ALA. For sensitivity analysis based only on studies recruiting at least 100 patients for patient-level and lesion-level analysis (Table 6), NBI had a higher sensitivity (100%) and FPR (33.53%) than HAL or 5-ALA at patient-level analysis; at lesion-level analysis, NBI was also found to have higher sensitivity (92.86%, IQR 88.69-97.3%) than HAL (93.16%, IQR 91.48-97.04). No data were available on grade and stage of disease, primary vs recurrent disease, and duration of follow-up, to enable additional sensitivity analyses.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis of studies with low to moderate RoB for index tests

| Study ID | Patient-level analysis | Lesion-level analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | ||

| NBI vs WLC (n=3) | NBI vs WLC (n=6) | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95.85 | 88.80 | 99.60 | |

| Specificity | 40.91 | 38.24 | 69.39 | 74.99 | 71.66 | 80.98 | |

| Positive predictive value | 94.12 | 80.0 | 97.06 | 79.84 | 75.87 | 82.02 | |

| Negative predictive value | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.33 | 97.90 | 100 | |

| False positive rate | 59.09 | 30.61 | 61.07 | 25.01 | 19.02 | 28.34 | |

| False negative rate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.15 | 0.40 | 11.20 | |

| HAL vs WLC (n=1) | HAL vs WLC (n=6) | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 83.33 | - | - | 95.00 | 92.97 | 98.21 | |

| Specificity | 92.75 | - | - | 83.33 | 76.38 | 88.65 | |

| Positive predictive value | 80.00 | - | - | 71.65 | 67.94 | 76.16 | |

| Negative predictive value | 93.81 | - | - | 99.17 | 94.20 | 99.89 | |

| False positive rate | 7.25 | - | - | 16.67 | 11.35 | 23.62 | |

| False negative rate | 16.67 | - | - | 5.00 | 1.79 | 7.03 | |

| 5-ALA vs WLC (n=1) | 5-ALA vs WLC (n=4) | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 100 | - | - | 95.51 | 94.75 | 96.33 | |

| Specificity | 91.18 | - | - | 77.82 | 71.90 | 79.26 | |

| Positive predictive value | 94.92 | - | - | 66.19 | 63.44 | 66.31 | |

| Negative predictive value | 100 | - | - | 100 | 99.12 | 100 | |

| False positive rate | 8.82 | - | - | 22.18 | 20.74 | 28.10 | |

| False negative rate | 0 | - | - | 4.49 | 3.67 | 5.25 | |

NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; WLC: white light cystoscopy; 5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexylaminolevulinate; NBI: narrow band imaging; NR: not reported.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of studies with more than 100 patients on Patient-level analysis and Lesion-level analysis

| Study ID | Patient-level analysis | Lesion-level analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | |||

| NBI vs WLC (n=2) | NBI vs WLC (n=3) | |||||||

| Sensitivity | 100 | - | - | 92.86 | 90.08 | 95.63 | ||

| Specificity | 65.78 | - | - | 76.85 | 73.01 | 81.58 | ||

| Positive predictive value | 76.63 | - | - | 68.42 | 61.17 | 71.79 | ||

| Negative predictive value | 100 | - | - | 100 | 98.82 | 100 | ||

| False positive rate | 33.53 | - | - | 23.15 | 18.42 | 26.99 | ||

| False negative rate | 0 | - | - | 7.14 | 4.37 | 9.92 | ||

| HAL vs WLC (n=1) | HAL vs WLC (n=4) | |||||||

| Sensitivity | 83.33 | - | - | 92.19 | 91.48 | 92.97 | ||

| Specificity | 92.75 | - | - | 85.74 | 77.33 | 87.42 | ||

| Positive predictive value | 80 | - | - | 73.26 | 70.05 | 77.94 | ||

| Negative predictive value | 93.81 | - | - | 96.13 | 91.70 | 99.68 | ||

| False positive rate | 7.25 | - | - | 14.26 | 12.58 | 22.67 | ||

| False negative rate | 16.67 | - | - | 6.84 | 5.24 | 7.65 | ||

| 5-ALA vs WLC (n=2) | 5-ALA vs WLC (n=2) | |||||||

| Sensitivity | 89.67 | - | - | 94.42 | - | - | ||

| Specificity | 75.05 | - | - | 80.28 | - | - | ||

| Positive predictive value | 77.65 | - | - | 66.33 | - | - | ||

| Negative predictive value | 75.47 | - | - | 98.25 | - | - | ||

| False positive rate | 24.96 | - | - | 19.72 | - | - | ||

| False negative rate | 10.33 | - | - | 5.58 | - | - | ||

NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; WLC: white light cystoscopy; 5-ALA: 5-aminolaevulinic acid; HAL: hexylaminolevulinate; NBI: narrow band imaging; NR: not reported.

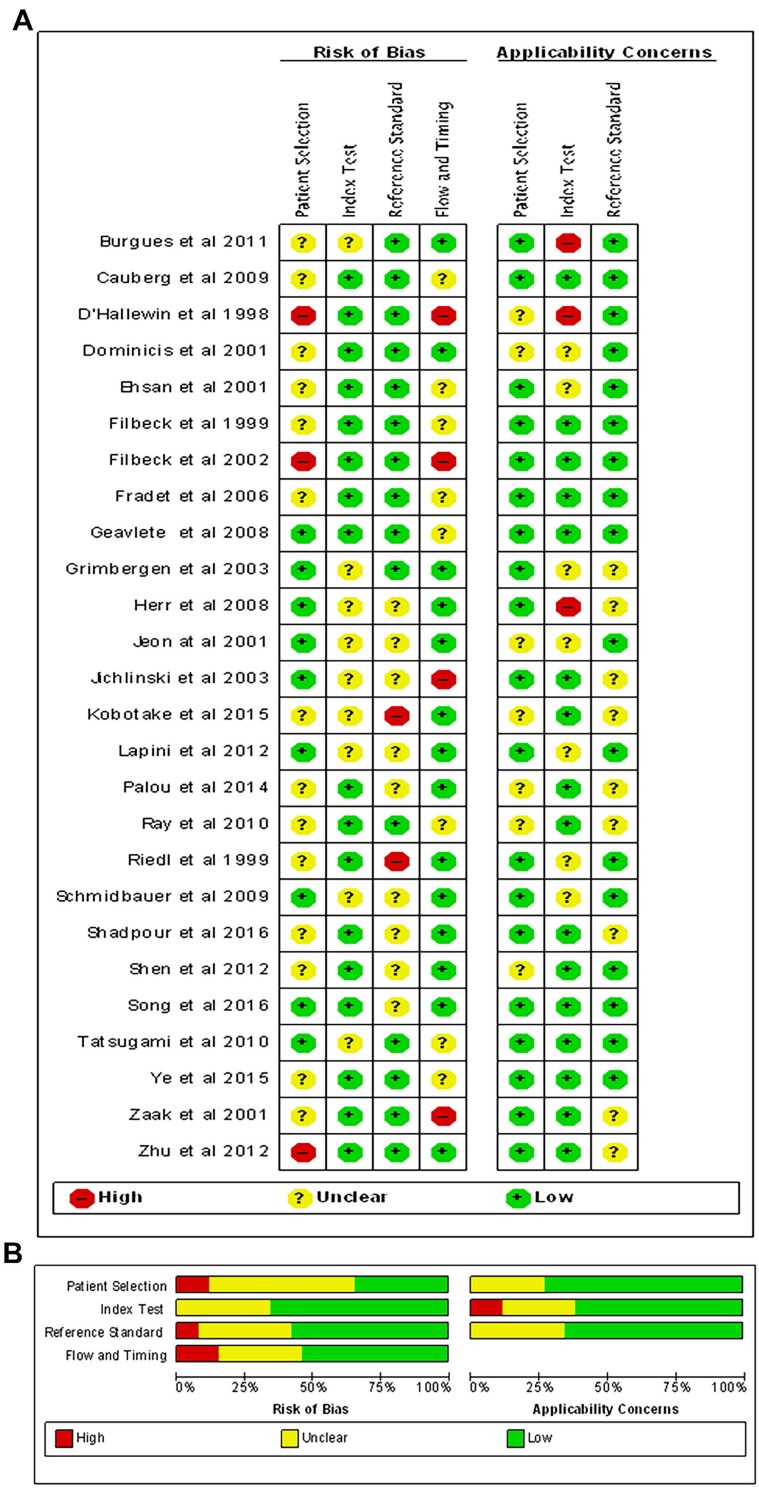

RoB of included studies

Figure 2 showed the RoBs assessment for studies included in the review using the QUADAS-2 tool. Overall, most studies (18/26) were judged as having low or unclear RoB across most domains. While patient selection was generally acceptable in the studies included, a few studies did not clearly report the inclusion criteria. All studies clearly reported methodology for the index test and reference standard, and were not considered a significant source of potential bias. Moreover, several studies were at high RoBs for the flow and timing, as many included targeted biopsies of suspicious lesions. These studies were excluded from diagnostic analyses because the FN data were not accurate.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of included studies. The Overall (A) and Study-level distribution plot for risk of bias using QUADAS-2 tool. Studies are deemed to be at high, low or unclear risk of bias for each domain. The review authors' judgments about each domain are presented as percentages across all included studies.

Discussion

Firstly, based on data from 26 studies, our systematic review found that almost all NMIBC diagnosed by WLC could be detected with PDD using 5-ALA, HAL or NBI. Second, the median rate of NBI or PDD-detected NMIBC outside WLC was positive (i.e. FPR >0), which indicates that NBI or PDD showed addition diagnostic benefits over WLC. Third, NBI could diagnose more NMIBC lesions than PDD-based HAL or 5-ALA-guided cystoscopies. Taken together, our results suggest that NBI could potentially be the best diagnostic intervention for NMIBC patients.

Intuitively, detection of more lesions and efficient treatment should lead to a better prognosis. In the present review, we have summarized the diagnostic accuracy of the new imaging-based diagnostic strategies for NMIBC. Our results indicate that the diagnostic accuracy of both PDD and NBI-guided cystoscopy were better than WLC. Moreover, we noted that NBI and PDD showed addition diagnostic benefits over WLC for NMIBC patients which would otherwise have been missed by conventional WLC. NBI was associated with the highest FP rate at lesion level, which suggests it play important role in minimizing missed lesions. Although data at patient level may be more relevant clinically, most of the included studies reported data at lesion level only. These findings demonstrate a numerical consistency, although a meta-analysis was not undertaken. In addition, whether these technologies should be applied to replace WLC or to augment WLC remains unclear. Since virtually all of the techniques assessed in this review had median sensitivities of 100% based on the reference standard of WLC, the review findings suggest that they are at least as good as WLC in detecting NMIBC, and are likely to surpass WLC in terms of diagnostic accuracy because of additional benefit of detecting more cases at patient-level and lesions at lesion-level. In this context, there are compelling reasons to adopt these strategies in clinical practice, although their clinical effectiveness in terms of important oncological outcomes such as progression and survival, or cost effectiveness, remains unproven. These present findings are not sufficient to trigger a change in clinical practice, while they do strongly suggest that new imaging-based technologies, in particular NBI, are promising and deserve further assessment through well-designed, protocol-driven prospective studies using standardized definitions and reference standards with robust follow-up protocols. The European Association of Urology guidelines (2018) acknowledge the improved detection rate of fluorescence-guided cystoscopy for malignant tumours, particularly CIS48. Future studies should investigate if the intervals of surveillance cystoscopies could be altered when PDD or NBI is used, and the necessity of re-TUR after PDD and NBI should be evaluated.

The most sensitive interventional diagnostic strategy for NMIBC patients remains unclear. Our study supports the assertion that new imaging-based techniques should be recommended. A high FPR reflects the inadequacy of WLC as a diagnostic procedure and a better detection of NMIBC with PDD or NBI compared with WLC. Although this appears counter intuitive (i.e. how can a histologically proven diagnosis of NMIBC based on an index test be classed as a 'false positive'), this is because all diagnostic accuracy measures must be calculated based on the results of the reference standard (i.e. WLC) as denominator. Consequently, a high FPR reflects the sub-optimal performance of WLC in diagnosing NMIBC, and better performance of the new imaging technologies.

PDD and NBI both aim at improving the visualization of bladder tumors. Randomized studies 17, 49, 50 have shown the superiority of PDD or NBI over WLC alone in tumor detection. SSY for PDD ranges from 76% to 97% compared with 46-80% for WLC. A random-effect meta-analysis using 2807 patients from 27 studies found a 21% increase in tumor detection with PDD over WLC in the pooled estimates for patients and biopsies13. NBI, another optical enhancement technology, increases the contrast between vasculature and superficial tissue structures of the mucosa by excluding the red spectrum of WLC. Several studies previously reported the enhanced diagnosis of bladder tumors with NBI cystoscopy compared with standard WLC alone 17, 18. Our previous meta-analysis indicated that NBI provides comparable or higher diagnostic precision than WLC and an additional 17% of patients and an additional 24% of tumors were detected by NBI 51. However, these studies did not use standardized diagnostic test accuracy definitions.

The previous review by Karaolides et al52 reported that both PDD using 5-ALA and HAL improves tumour detection after TURBT compared with WLC. Burger et al53 reported that PDD using HAL significantly improves the detection of bladder tumours leading to a reduction of recurrence at 9-12 months. Moreover, Li et al indicated that NBI provides comparable or higher diagnostic precision than WLC 51 and the other meta-analysis54 evaluated WLC, PDD- and NBI-assisted TUR in the NMIBC patients, suggesting both PDD and NBI for NMIBC were superior to WLC in lowering the recurrence rate. Therefore, although a clear benefit for PDD and NBI have been found for improving the detection of NMIBC, the best diagnostic strategy remains controversial. The findings support that NBI might be the most sensitive interventional treatment for NMIBC patients.

The strengths of our study include the stringent methodology used to synthesize the evidence, including adhering to PRISMA guidelines, using standardized definitions of diagnostic test accuracy, undertaking a systematic and comprehensive search strategy, and utilizing explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria in relation to design of primary studies, population, index tests, reference standard and outcomes. Quality assessment was also performed using QUADAS-2. However, potential study limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, any biases and inaccuracies within individual studies would be reflected in our analysis. The greatest threat to the validity of the study is heterogeneity in study designs, recruitment criteria, interventions, or endpoint assessments. The lack of data on key clinical variables may also introduce clinical heterogeneity, including grade and stage of disease, duration of follow-up, and primary vs recurrent disease, prevented further sensitivity analyses. Also, we could not explore the diagnostic performance of PDD and NBI in tumour recurrence or intravesical instillation settings compared with WLC due to lack of data. However, we have attempted to minimize biases by applying rigorous selection criteria during the design phase of our study, standardizing data extraction and performing several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings.

In summary, NBI appears to be the most sensitive diagnostic intervention for NMIBC patients compared with either HAL or 5-ALA, both of which are PDD-based, based on diagnostic test accuracy assessment using WLC as a reference standard. NBI, HAL and 5-ALA all demonstrated median sensitivities of 100%, and appeared to have the ability to detect additional cases of NMIBC both at patient and lesion levels. Sensitivity analysis suggests that NBI can diagnose more additional NMIBC lesions compared with either HAL or 5-ALA. The findings confirm the excellent diagnostic performance of these new imaging-based technologies in diagnosing NMIBC in comparison with the present standard using WLC, although well-designed prospective studies with long-term follow-up may shed more light on their impact on key oncological outcomes such as progression and survival.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81802530, 81772719, 81772728, 91740119); Guangdong Medical Research Fundation (A2018330); Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (A201947); Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (Grant No. 201604020156, 201604020177, 201707010116); National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (Grant No. 2018A030313564, 2018A030310250, 2016A030313321, 2015A030311011, 2015A030310122, S2013020012671, 07117336, 10151008901000024). Yixian Youth project of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (YXQH201812).

References

- 1.Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor A, Jemal A, Bray F. Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Overview and Recent Trends. European urology; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babjuk M, Bohle A, Burger M, Guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Ta,T1 and CIS) European Association of Urology Web site. http://uroweb.org/guideline/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, Kaasinen E, Bohle A, Palou-Redorta J. et al. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. European urology. 2011;59:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, He W, Huang J, Wang B, Li H, Cai Q. et al. LNMAT1 promotes lymphatic metastasis of bladder cancer via CCL2 dependent macrophage recruitment. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pawinski A, Sylvester R, Kurth KH, Bouffioux C, van der Meijden A, Parmar MK. et al. A combined analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, and Medical Research Council randomized clinical trials for the prophylactic treatment of stage TaT1 bladder cancer. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group and the Medical Research Council Working Party on Superficial Bladder Cancer. The Journal of urology. 1996;156:1934–40. discussion 40-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas F, Noon AP, Rubin N, Goepel JR, Catto JW. Comparative outcomes of primary, recurrent, and progressive high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. European urology. 2013;63:145–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He W, Zhong G, Jiang N, Wang B, Fan X, Chen C. et al. Long noncoding RNA BLACAT2 promotes bladder cancer-associated lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:861–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI96218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwaibold HE, Sivalingam S, May F, Hartung R. The value of a second transurethral resection for T1 bladder cancer. BJU international. 2006;97:1199–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L. et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. European urology. 2006;49:466–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. discussion 75-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimbergen MCM, van Swol CFP, Jonges TGN, Boon TA, van Moorselaar RJA. Reduced Specificity of 5-ALA Induced Fluorescence in Photodynamic Diagnosis of Transitional Cell Carcinoma after Previous Intravesical Therapy. European Urology. 2003;44:51–6. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniltchenko DI, Riedl CR, Sachs MD, Koenig F, Daha KL, Pflueger H. et al. Long-term benefit of 5-aminolevulinic acid fluorescence assisted transurethral resection of superficial bladder cancer: 5-year results of a prospective randomized study. The Journal of urology. 2005;174:2129–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181814.73466.14. discussion 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriegmair M, Baumgartner R, Knuchel R, Stepp H, Hofstadter F, Hofstetter A. Detection of early bladder cancer by 5-aminolevulinic acid induced porphyrin fluorescence. The Journal of urology. 1996;155:105–9. discussion 9-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mowatt G, N'Dow J, Vale L, Nabi G, Boachie C, Cook JA. et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of bladder cancer compared with white light cystoscopy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:3–10. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310001364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuzillet Y, Methorst C, Schneider M, Lebret T, Rouanne M, Radulescu C. et al. Assessment of diagnostic gain with hexaminolevulinate (HAL) in the setting of newly diagnosed non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with positive results on urine cytology. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:1135–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naito S, Algaba F, Babjuk M, Bryan RT, Sun YH, Valiquette L, The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society (CROES) Multicentre Randomised Trial of Narrow Band Imaging-Assisted Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour (TURBT) Versus Conventional White Light Imaging-Assisted TURBT in Primary Non-Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Patients: Trial Protocol and 1-year Results. European urology; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naselli A, Introini C, Timossi L, Spina B, Fontana V, Pezzi R. et al. A randomized prospective trial to assess the impact of transurethral resection in narrow band imaging modality on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer recurrence. Eur Urol. 2012;61:908–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Z, Hu J, Song X, Li F, Zhao X, Chen S. et al. A comparison of NBI and WLI cystoscopy in detecting non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A prospective, randomized and multi-center study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10905. doi: 10.1038/srep10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geavlete B, Multescu R, Georgescu D, Stanescu F, Jecu M, Geavlete P. Narrow band imaging cystoscopy and bipolar plasma vaporization for large nonmuscle-invasive bladder tumors-results of a prospective, randomized comparison to the standard approach. Urology. 2012;79:846–51. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naito S, Algaba F, Babjuk M, Bryan RT, Sun YH, Valiquette L. et al. The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society (CROES) Multicentre Randomised Trial of Narrow Band Imaging-Assisted Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour (TURBT) Versus Conventional White Light Imaging-Assisted TURBT in Primary Non-Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Patients: Trial Protocol and 1-year Results. Eur Urol. 2016;70:506–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L. et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB. et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155:529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu YP, Shen YJ, Ye DW, Wang CF, Yao XD, Zhang SL. et al. Narrow-band imaging flexible cystoscopy in the detection of clinically unconfirmed positive urine cytology. Urologia internationalis. 2012;88:84–7. doi: 10.1159/000333119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaak D, Kriegmair M, Stepp H, Stepp H, Baumgartner R, Oberneder R. et al. Endoscopic detection of transitional cell carcinoma with 5-aminolevulinic acid: results of 1012 fluorescence endoscopies. Urology. 2001;57:690–4. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatsugami K, Kuroiwa K, Kamoto T, Nishiyama H, Watanabe J, Ishikawa S. et al. Evaluation of narrow-band imaging as a complementary method for the detection of bladder cancer. Journal of endourology. 2010;24:1807–11. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song PH, Cho S, Ko YH. Decision Based on Narrow Band Imaging Cystoscopy without a Referential Normal Standard Rather Increases Unnecessary Biopsy in Detection of Recurrent Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma Early after Intravesical Instillation. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:273–80. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen YJ, Zhu YP, Ye DW, Yao XD, Zhang SL, Dai B. et al. Narrow-band imaging flexible cystoscopy in the detection of primary non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a "second look" matters? Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:451–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-011-0036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shadpour P, Emami M, Haghdani S. A Comparison of the Progression and Recurrence Risk Index in Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Tumors Detected by Narrow-Band Imaging Versus White Light Cystoscopy, Based on the EORTC Scoring System. Nephrourol Mon. 2016;8:e33240. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.33240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidbauer J, Remzi M, Klatte T, Waldert M, Mauermann J, Susani M. et al. Fluorescence cystoscopy with high-resolution optical coherence tomography imaging as an adjunct reduces false-positive findings in the diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. European urology. 2009;56:914–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riedl CR, Plas E, Pfluger H. Fluorescence detection of bladder tumors with 5-amino-levulinic acid. Journal of endourology. 1999;13:755–9. doi: 10.1089/end.1999.13.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray ER, Chatterton K, Khan MS, Chandra A, Thomas K, Dasgupta P. et al. Hexylaminolaevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy in patients previously treated with intravesical bacille Calmette-Guerin. BJU Int. 2010;105:789–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palou J, Hernandez C, Solsona E, Abascal R, Burgues JP, Rioja C. et al. Effectiveness of hexaminolevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy for the diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in daily clinical practice: a Spanish multicentre observational study. BJU international. 2015;116:37–43. doi: 10.1111/bju.13020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapini A, Minervini A, Masala A, Schips L, Pycha A, Cindolo L. et al. A comparison of hexaminolevulinate (Hexvix((R))) fluorescence cystoscopy and white-light cystoscopy for detection of bladder cancer: results of the HeRo observational study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3634–41. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobatake K, Mita K, Ohara S, Kato M. Advantage of transurethral resection with narrow band imaging for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:1097–102. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jichlinski P, Guillou L, Karlsen SJ, Malmstrom PU, Jocham D, Brennhovd B. et al. Hexyl aminolevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy: new diagnostic tool for photodiagnosis of superficial bladder cancer-a multicenter study. The Journal of urology. 2003;170:226–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000060782.52358.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeon SS, Kang I, Hong JH, Choi HY, Chai SE. Diagnostic efficacy of fluorescence cystoscopy for detection of urothelial neoplasms. Journal of endourology. 2001;15:753–9. doi: 10.1089/08927790152596370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herr HW, Donat SM. A comparison of white-light cystoscopy and narrow-band imaging cystoscopy to detect bladder tumour recurrences. BJU international. 2008;102:1111–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimbergen MC, van Swol CF, Jonges TG, Boon TA, van Moorselaar RJ. Reduced specificity of 5-ALA induced fluorescence in photodynamic diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma after previous intravesical therapy. European urology. 2003;44:51–6. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geavlete B, Multescu R, Georgescu D, Geavlete P. Hexaminolevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy and transurethral resection of the bladder in noninvasive bladder tumors. Journal of endourology. 2009;23:977–81. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fradet Y, Grossman HB, Gomella L, Lerner S, Cookson M, Albala D. et al. A comparison of hexaminolevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy and white light cystoscopy for the detection of carcinoma in situ in patients with bladder cancer: a phase III, multicenter study. The Journal of urology. 2007;178:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.028. discussion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Filbeck T, Roessler W, Knuechel R, Straub M, Kiel HJ, Wieland WF. Clinical results of the transurethreal resection and evaluation of superficial bladder carcinomas by means of fluorescence diagnosis after intravesical instillation of 5-aminolevulinic acid. Journal of endourology. 1999;13:117–21. doi: 10.1089/end.1999.13.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filbeck T, Pichlmeier U, Knuechel R, Wieland WF, Roessler W. Do patients profit from 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence diagnosis in transurethral resection of bladder carcinoma? Urology. 2002;60:1025–8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01961-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehsan A, Sommer F, Haupt G, Engelmann U. Significance of fluorescence cystoscopy for diagnosis of superficial bladder cancer after intravesical instillation of delta aminolevulinic acid. Urologia internationalis. 2001;67:298–304. doi: 10.1159/000051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Dominicis C, Liberti M, Perugia G, De Nunzio C, Sciobica F, Zuccala A. et al. Role of 5-aminolevulinic acid in the diagnosis and treatment of superficial bladder cancer: improvement in diagnostic sensitivity. Urology. 2001;57:1059–62. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00948-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D'Hallewin MA, Vanherzeele H, Baert L. Fluorescence detection of flat transitional cell carcinoma after intravesical instillation of aminolevulinic acid. Am J Clin Oncol. 1998;21:223–5. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cauberg EC, Kloen S, Visser M, de la Rosette JJ, Babjuk M, Soukup V. et al. Narrow band imaging cystoscopy improves the detection of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urology. 2010;76:658–63. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burgues JP, Conde G, Oliva J, Abascal JM, Iborra I, Puertas M. et al. [Hexaminolevulinate photodynamic diagnosis in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: experience of the BLUE group] Actas urologicas espanolas. 2011;35:439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Babjuk M, Bohle A, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Comperat EM. et al. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Update 2016. Eur Urol. 2017;71:447–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babjuk M, Soukup V, Petrik R, Jirsa M, Dvoracek J. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-induced fluorescence cystoscopy during transurethral resection reduces the risk of recurrence in stage Ta/T1 bladder cancer. BJU international. 2005;96:798–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gkritsios P, Hatzimouratidis K, Kazantzidis S, Dimitriadis G, Ioannidis E, Katsikas V. Hexaminolevulinate-guided transurethral resection of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer does not reduce the recurrence rates after a 2-year follow-up: a prospective randomized trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:927–33. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0603-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li K, Lin T, Fan X, Duan Y, Huang J. Diagnosis of narrow-band imaging in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of urology: official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2013;20:602–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karaolides T, Skolarikos A, Bourdoumis A, Konandreas A, Mygdalis V, Thanos A. et al. Hexaminolevulinate-induced fluorescence versus white light during transurethral resection of noninvasive bladder tumor: does it reduce recurrences? Urology. 2012;80:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burger M, Grossman HB, Droller M, Schmidbauer J, Hermann G, Dragoescu O. et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with hexaminolevulinate cystoscopy: a meta-analysis of detection and recurrence based on raw data. Eur Urol. 2013;64:846–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JY, Cho KS, Kang DH, Jung HD, Kwon JK, Oh CK. et al. A network meta-analysis of therapeutic outcomes after new image technology-assisted transurethral resection for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: 5-aminolaevulinic acid fluorescence vs hexylaminolevulinate fluorescence vs narrow band imaging. BMC cancer. 2015;15:566. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1571-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burgues JP, Conde G, Oliva J, Abascal JM, Iborra I, Puertas M. et al. [Hexaminolevulinate photodynamic diagnosis in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: experience of the BLUE group] Actas urologicas espanolas. 2011;35:439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.