Abstract

β-Catenin is a central player of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates cell–cell adhesion and may promote leukemia cell proliferation. We examined whether JS-K, an NO-donating prodrug, modulates the Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway in Jurkat T-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia cells. JS-K inhibited Jurkat T cell growth in a concentration and time-dependent manner. The IC50s for cell growth inhibition were 14 ± 0.7 and 9 ± 1.2 μM at 24 and 48 h, respectively. Treatment of the cells with JS-K for 24 h, caused a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis from 16 ± 3.3% at 10 μM to 74.8 ± 2% at 100 μM and a decrease in proliferation. This growth inhibition was also due, in part, to alterations in the different phases of the cell cycle. JS-K exhibited a dose-dependent cytotoxicity as measured by LDH release at 24 h. However, between 2 and 8 h, LDH release was less than 20% for any indicated JS-K concentration. The β-catenin/TCF-4 transcriptional inhibitory activity was reduced by 32 ± 8, 63 ± 5, and 93 ± 2% at 2, 10, and 25 μM JS-K, respectively, based on luciferase reporter assays. JS-K reduced nuclear β-catenin and cyclin D1 protein levels, but cytosolic β-catenin expression did not change. Based on a time-course assay of S-nitrosylation of proteins by a biotin switch assay, S-nitrsolyation of nuclear β-catenin was determined to precede its degradation. A comparison of the S-nitrosylated nuclear β-catenin to the total nuclear β-catenin showed that β-catenin protein levels were degraded at 24 h, while S-nitrosylation of β-catenin occurred earlier at 0–6 h. The NO scavenger PTIO abrogated the JS-K mediated degradation of β-catenin demonstrating the need for NO.

Keywords: Leukemia, JS-K, S-nitrosylation, β-Catenin, Chemoprevention

1. Introduction

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignant disease in children accounting for 70% of all childhood leukemias [1]. ALLs with certain chromosomal translocations constitute a high-risk subgroup of leukemia found in approximately 60% of infants. They are particularly resistant to conventional chemotherapy, thus requiring alternative treatment strategies [2]. Agents that induce nitric oxide (NO) or nitric oxide donors have recently emerged as novel cancer chemopreventive agents. Evidence is accumulating for the role of NO as a new oncopreventive agent and more recently as a novel therapeutic to overcome tumor cell resistance [3]. Nitric oxide can also prevent or stimulate cell death by apoptosis, depending on cell type and dose [4,5].

O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl) 1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (JS-K) is a member of the arylated diazeniumdiolate class of nitric oxide prodrugs that has shown promise as an anti-cancer drug [6,7]. Due to the poor bioavailability of gaseous NO, drugs that release NO such as diazeniumdiolates are used as donors of NO [8]. JS-K has shown potent anti-leukemia activity both in vitro and in vivo using a xenograft model [6]. JS-K has also been shown to inhibit hepatoma Hep 3B cell proliferation [9], enhance arsenic and cisplatin-induced cytolethality in arsenic-transformed rat liver cells [10], and induce apoptosis in human multiple myeloma cell lines [11]. In addition, J-SK was also shown to be effective against leukemia, renal, prostate, and brain cancer cells [12,13].

The protein β-catenin is a central player of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates cell–cell adhesion and may promote leukemia cell proliferation [14]. It is known that elevated levels of β-catenin-targeted genes including cyclin D1 promote genetic instability, leading to tumorigenesis [15,16]. Small molecules modulating the β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway are thus attractive as cancer therapeutic agents.

In the present study, we aimed to characterize the molecular basis of JS-K action. We specifically tried to delineate whether JS-K may modulate the Wnt/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway, including expression of its downstream target gene, cyclin D1, in Jurkat T-ALL cells. β-Catenin is expressed in T-ALL cells, tumor lines of hematopoietic origin, and primary leukemia cells but is undetectable in normal peripheral blood T cells. JS-K induces differentiation and apoptosis in human myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells [6,9]. However, these cells poorly express β-catenin whereas among the leukemia cell lines, β-catenin is expressed in high levels in Jurkat T cells [14,17]. Therefore, in the present study we evaluated the effects of the nitric oxide-releasing produg JS-K on β-catenin in Jurkat T cells.

In view of the fact that the plasma and cellular milieux contain reactive species that can rapidly inactivate NO, it has been postulated that NO is stabilized by a carrier molecule that preserves its biological activity. Reduced thiol species are candidates for this role, reacting readily in the presence of aerobic NO to yield biologically active S-nitrosothiols that are more stable than NO [18,19]. In this study we examined the effect of JS-K on proliferation and apoptosis in Jurkat T cells and also evaluated whether JS-K’s effects on β-catenin could be NO-mediated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and cell culture

O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (JS-K, Fig. 1) was synthesized as previously described [20]. Stock solutions (100 mM) were made in DMSO; final DMSO concentration was adjusted in all media to 1%. Jurkat cells (ATCC TIB-152, Manassas, VA) were grown per ATCC instructions. 2-(4-Carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (carboxy-PTIO), methylmethanethiosulfate (MMTS), neocuproine, sodium ascorbate, streptavidin-agarose and Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 3-([3-Cholamidopropyl]dimethylamino)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and N-[6-(Biotinamido) hexyl]-3′ (2′-pyridyldithio) propionamide (Biotin-HPDP) were from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL).

Fig. 1.

Structure of JS-K (O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl) 1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate).

2.2. LDH release assay

For determination of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, Jurkat cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were incubated in 96-well plates with different concentrations of JS-K. After incubation for 2, 4, 8 or 24 h, LDH activity in the supernatant was assessed using the LDH-Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Ann Arbor, MI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytotoxicity was calculated as a percentage based on the LDH activity released from cells that had been treated with JS-K compared with LDH activity from cultures incubated with Triton X-100. The % of LDH release was determined using the formula (E – C)/(T – C) × 100, where E is the experimental absorbance of cell cultures, C is the control absorbance of cell-free culture medium, and T is the absorbance corresponding to the maximal (100%) LDH release of Triton-lysed cells [21].

2.3. Cell growth inhibition and trypan blue dye exclusion assay

The growth inhibitory effect of JS-K on Jurkat T cells was determined using a colorimetric MTT assay kit (Roche; Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 13.7 × 103 cells/well and, following overnight incubation, JS-K was added to the culture medium. Viable cells were quantified with MTT substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Growth inhibition was expressed as percentage of the corresponding control. Aliquots of cells were counted using a hemacytometer and tested for viability by the trypan blue dye (Sigma, St Louis, MO) exclusion method. Cells that stained blue were considered “non-viable”.

2.4. Assay for apoptosis

Jurkat cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mL) were treated for 24 h with various concentrations of JS-K. Cells were washed with and resuspended in 1X Binding Buffer (Annexin V binding buffer, 0.1 M HEPES/NaOH (pH 7.4), 1.4 M NaCl, 25 mM CaCl2; BD BioSciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Then 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC (final concentration: 0.5 μg/mL) was added followed by propidium iodide as a counterstain (final concentration 20 μg/mL). The cells were then incubated at room temperature for 5–15 min in the dark. Finally, the cells were transferred to FACS tubes for analysis. Percentage of apoptotic cells were obtained using a Becton Dickinson LSR II equipped with a single argon ion laser. For each subset, about 10,000 events were analyzed. All parameters were collected in list mode files. Data was analyzed by Flow Jo software.

2.5. Measurement of NO release

Jurkat cells (1 × 105 cells/mL) were exposed to JS-K treatment in the apprpriate medium. Since RPMI 1640 medium contains high level of nitrate, we replaced it with McCoy’s medium which contains low nitrate for this study. NO release was measured in the culture medium using a nitrate/nitrite colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical Co., MI, USA). Briefly, samples were incubated with nitrate reductase and NADPH cofactor for 2 h to convert nitrate into nitrite. The total amount of NO was then determined using the Griess reagent. A standard curve was generated using known concentrations of nitrate assayed at 540 nm using a microplate reader. The NO concentrations in samples were calculated using the standard curve. The results are expressed as μM nitrate/nitrite released by the cells.

2.6. Cell proliferation

Jurkat cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mL) were treated for 24 h with various concentrations of JS-K. PCNA was determined using an ELISA Kit (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.7. Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle phase distributions of control and treated Jurkat cells were obtained using a Coulter Profile XL equipped with a single argon ion laser. For each subset, >10,000 events were analyzed. All parameters were collected in list mode files. Data were analyzed on a Coulter XL Elite Work station using the Software programs Multigraph™ and Multicycle™. Cells (0.5 × 106) were fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min at −20 °C, pelleted (5000 rpm × 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended and incubated in PBS containing 1% FBS/0.5% NP-40 on ice for 5 min. Cells were washed again in 500 μL of PBS/1% FBS containing 40 μg/mL propidium iodide (used to stain for DNA) and 200 μg/mL RNase type IIA, and analyzed within 30 min by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in G0/G1, G2/M, and S phases was determined form DNA content histograms.

2.8. Plasmids, transient transfection and reporter gene assay

Transient transfection was performed on Jurkat T cells by electroporation using BioRad Gene Pulsar. Briefly, 106 cells were electroprated with 1 μg of luciferase reporter constructs TOPflash or FOPflash (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) and 500 ng of pSV-b-gal vector as internal control. TOPflash contains three copies of the TCF/LEF binding site (AAGATCAAAGGGGGT) upstream of a TK minimal promoter. FOPflash contains a mutated TCF/LEF binding site (AAGGCCAAAGGGGGT). Fresh medium was added to cells and 4 h post-transfection, cells were treated for 24 h with JS-K. Luciferase activity was measured per manufacturer’s instructions and β-galactosidase activity was measured using standard protocols. The activity was normalized to β-gal values and expressed as relative fold compared to control.

2.9. Western blot analysis

Jurkat cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were treated with different concentrations of JS-K for 24 h. The preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts was performed using the Nuclear Extraction Kit (Panomics, Redwood City, CA). Equal amounts (60 μg) of the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies were against the following at the dilutions indicated: β-catenin, 1:1000; α-actin, 1:1000; and cyclin D1, 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:5000) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Immunoreactive proteins were detected by chemiluminescence (Amersham, Rockford, IL).

2.10. Purification of S-nitrosylated proteins

The biotin switch assay was used as previously described [22]. Jurkat cells (1 × 106 cells) were treated with different concentrations of JS-K for 24 h after which they were lysed for 20 min in HEN buffer (25 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, pH 7.7) containing 0.1% SDS and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. Lysate proteins (800 μg) were incubated with four volumes of HEN buffer-1 containing 2.5% SDS and 20 mM methylmethanethiosulfate (MMTS) for 1 h at 50 °C under agitation to block free thiols. MMTS was separated from proteins by cold acetone precipitation. Protein pellets were then resuspended in 100 μL HEN buffer 1 containing 1% SDS adjusted to pH 6.8 to prevent biotinylation of primary amines. S-Nitrosothiols were decomposed by adding 5 mM ascorbate followed by incubation with 2 mM biotin-HPDP(N-[6-(Biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide) for 1 h in the dark at room temperature while samples were rotated. Another acetone precipitation was performed to remove excess biotin-HPDP. Biotinylated proteins were then purified using streptavidin-agarose beads, and biotinylated proteins were detected by Western blot with anti-biotin antibodies, using Vectastain Elite ABC kit and ECL reagent (Amersham, Rockford, IL). To assess S-nitrosylation of a specific protein, β-catenin, 50 μL of elution buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.7, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 M 2-mercaptoethanol) and 50 μL of 2X SDS sample buffer were added to the agarose beads. After boiling, SDS-PAGE was performed. The samples were protected from light during the preparations of proteins by the Biotin Switch method. For control samples, sodium ascorbate was omitted, preventing the reduction of S-nitrothiols [23].

2.11. Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SEM for at least three different sets of plates and treatment groups. Statistical comparison among the groups was performed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference method.

3. Results

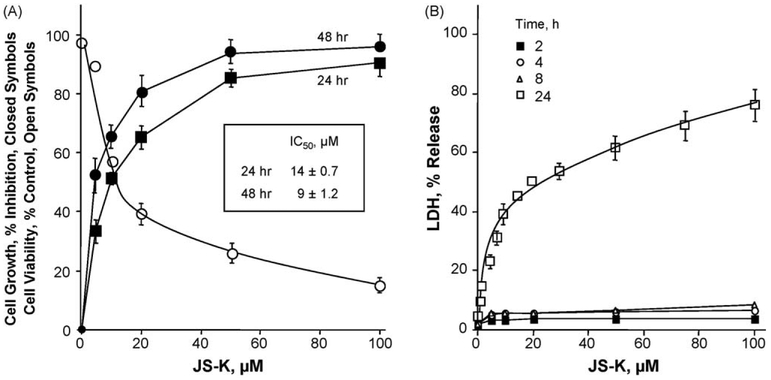

3.1. JS-K strongly inhibits the growth of human leukemia Jurkat T cells

Cells were treated with several concentrations of JS-K for 24–48 h and compared to untreated controls in an MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, JS-K strongly inhibited cell growth in a concentration and time-dependent manner. The IC50s for cell growth inhibition were 14 ± 0.7 and 9 ± 1.2 μM at 24 and 48 h, respectively. JS-K caused cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner after 24 h. At its IC50, there was a 40–43% increase in LDH release compared to untreated control (Fig. 2B). LDH release for shorter durations of treatment (2, 4, and 8 h) was less than 20% for the indicated concentrations of JS-K. Further, viability studies using trypan blue (Fig. 2A) showed similar results to that obtained with the MTT assay for growth inhibition, IC50 values were not significantly different.

Fig. 2.

Concentration- and time-dependent inhibition of Jurkat T cell growth by JS-K and its cytotoxicity. Cells were treated with various concentrations of JS-K as described in Section 2. (A) Cell numbers were determined at 24 and 48 h from which IC50s for growth inhibition were determined. (B) Cells were treated for 2, 4, 8, and 24 h with various concentrations of JS-K including Triton X-100 as positive control. LDH released from the cells was quantified and cytotoxicity was plotted as a percentage of total LDH released from Triton X-100. Results represent means ± SEM of three different experiments performed in triplicate.

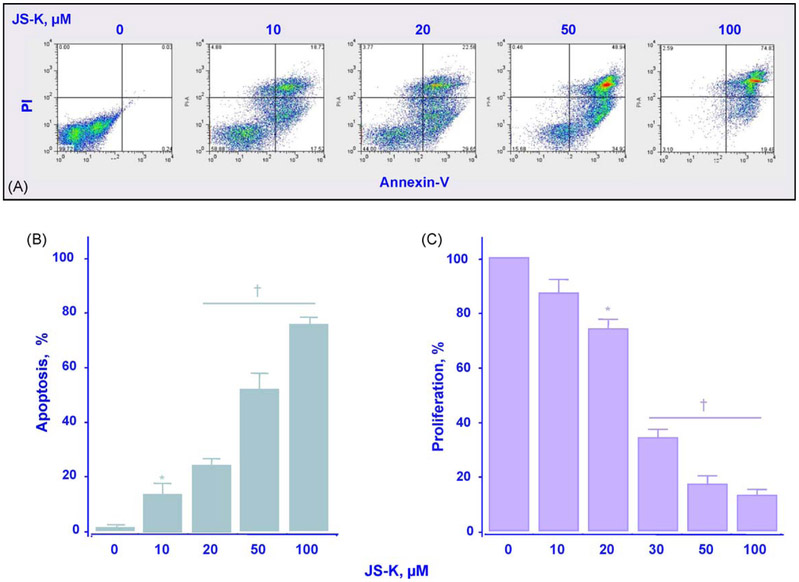

3.2. Apoptosis, cell cycle, cell proliferation and kinetics of NO release

Two determinants of cellular mass are proliferation and apoptosis. We examined the effects of different concentrations of JS-K after 24 h of treatment on these two parameters. Fig. 3A and B shows that the percentage of apoptotic cells increased in a concentration-dependent manner, from 16 ± 3.3% at 10 μM to 74.8 ± 2% at 100 μM. At the same time, the proliferation marker, PCNA, decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

JS-K induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation of Jurkat T cells. Cells were treated with JS-K at the concentration indicated for 24 h after which the cells were stained with annexin and propidium iodide and subjected to flow cytometric analysis as described in Section 2 (Panel A). The percentage of apoptotic cells increased in a concentration-dependent manner (Panel B). Panel C, cells were treated with JS-K at the concentrations indicated for 24 h after which PCNA expression was determined by flow cytometry and expressed as percentage positive cells as described in Section 2. Results are mean ± SEM of three different experiments. *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01 compared with untreated cells.

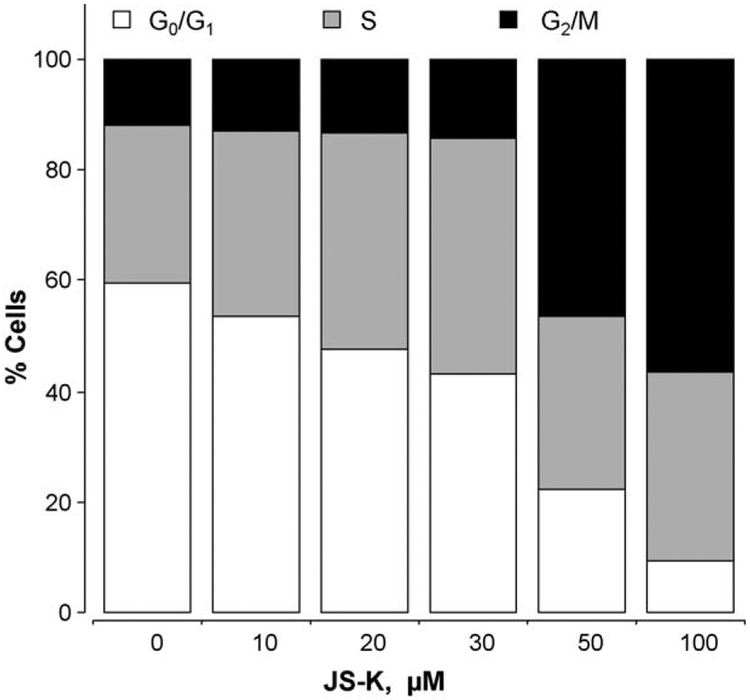

The effects of JS-K on cell cycle were assessed to determine whether the growth inhibition was due to alterations in the different phases. JS-K reduced the G0/G1 phase population and increased the population in G2/M phase accordingly (Fig. 4). Following 24 h of treatment with 10 μM JS-K, population of cells in G0/G1 phase was reduced from 59.6% to 53.6% and cells in the S phase increased from 28.5% to 33.6%, whereas the population in G2/M phase did not change appreciably (11.9–12.8%). These changes became more pronounced at 50 μM (G0/G1 was reduced to 22.1%, whereas G2/M showed an increase to 46.4%), however, the population of the cells in the S phase essentially remained constant (31.5%).

Fig. 4.

Effect of JS-K on cell cycle in Jurkat T cells. Cells were treated for 24 h with various concentrations of JS-K, and their cell cycle phase distribution was determined by flow cytometry, as described in Section 2. Results are representative of two different experiments. This study was repeated twice generating results within 10% of those presented here.

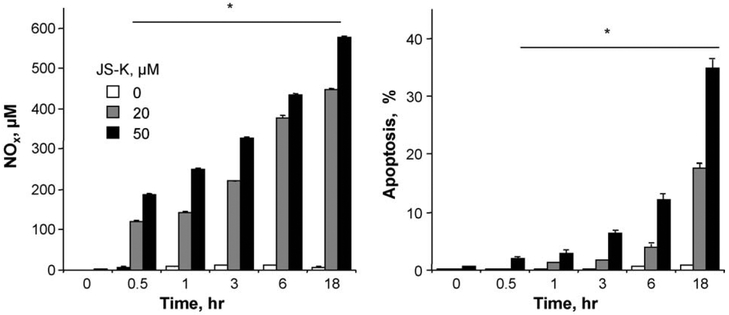

The kinetics of apoptotic cell death was compared to the kinetics of NO release by JS-K. Cells treated with either 20 or 50 μM JS-K at various indicated time intervals were evaluated for apoptotic populations by Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide staining, followed by flow cytometry. NO release was evaluated from the same cell culture supernatants. JS-K induced apoptosis in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5). The release of NO increased at 20 μM and 50 μM JS-K as a function of time also, up to 18 h (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that the kinetics of NO release and the kinetics of apoptosis are associated. It should be noted that we expected a bell-shaped curve for the release of NO as we have reported for other NO-donating compounds [24]. However, those studies were done in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of NO release and apoptosis. Cells were treated with either 20 or 50 μM JS-K after which apoptosis and NO levels were measured as a function of time. JS-K induced apoptosis in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. The release of NO also increased at 20 μM and 50 μM JS-K as a function of time. Results are mean ± SEM of three different experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to respective untreated cells.

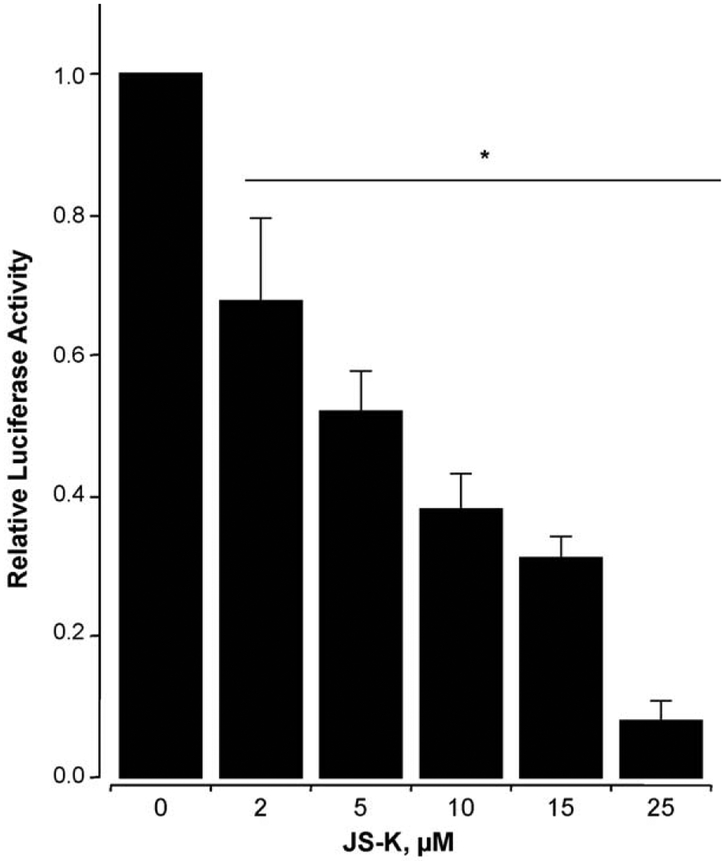

3.3. JS-K strongly inhibits β-catenin/TCF transcriptional activity

Jurkat T cells were electroporated with TOPflash or FOPFlash reporters and β-gal vectors as described, followed by treatment with JS-K (2–25 μM) for 24 h, and luciferase reporter activity was measured. JS-K showed strong inhibitory activity (Fig. 6).JS-K at 2, 10, and 25 μM reduced the transcriptional activity by 32 ± 8%, 63 ± 5%, and 93 ± 2% respectively, compared to vehicle-treated control. The IC50 for inhibition of β-catenin/TCF transcriptional activity was 5.2 ± 0.6 μM. Cells that were transfected with the vector containing mutated TCF/LEF binding sequence as control did not show any transcriptional activity in the absence or presence of JS-K confirming the specificity of the TOPflash reporter used (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of TCF-4 responsive reporter gene by JS-K. Jurkat T cells, cotransfected with luciferase reporter plasmids (TOP or FOP) and the pSV-ßgal as in Section 2 were treated with various concentrations of JS-K for 24 h. Relative TCF activity (fold) of treated cells is shown (DMSO control was set as 1); values are mean ± SEM of three different experiments performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05 compared to DMSO treated control cells.

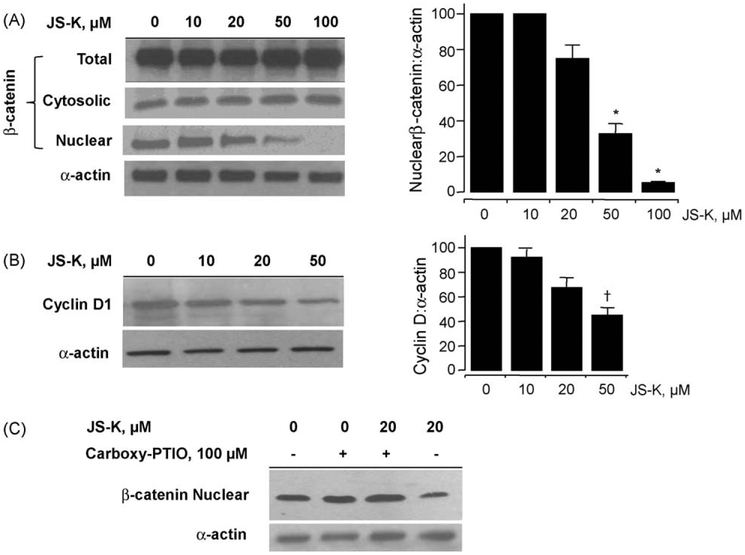

3.4. JS-K reduces nuclear β-catenin expression via an NO-dependent mechanism

Since β-catenin/TCF-4 transcriptional activity was inhibited by JS-K, the possibility of down-regulation of β-catenin expression by JS-K was examined by assessing its cellular levels through immunoblotting. Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were isolated from cells treated with various concentrations of JS-K for 24 h. JS-K reduced nuclear β-catenin protein levels at 20, 50, and 100 μM by 27 ± 2.9%, 67 ± 2%, and 92 ± 1%, respectively (Fig. 7A). However, JS-K had no appreciable effect on cytosolic β-catenin protein level or on its total cellular level. Next, we examined whether the decrease in nuclear β-catenin expression affected cyclin D1 levels (Fig. 7B). Of the several genes whose transcription is regulated by β-catenin/TCF-4, Cyclin D1 plays an important role in the process of carcinogenesis [25]. Cyclin D1 protein level was partially downregulated, and this down-regulation occurred between 20 and 50 μM JS-K. Since JS-K is capable of releasing NO, we further examined whether JS-K decreased the nuclear β-catenin levels via an NO-mediated mechanism. We used the NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO (2-carboxyphenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide) which reacts stoichiometrically with NO. Co-treatment of the cells with carboxy-PTIO and 20 μM JS-K for 24 h (Fig. 7C) abrogated the decrease in nuclear β-catenin expression demonstrating that NO is required for this decrease.

Fig. 7.

JS-K reduces nuclear β-catenin and cyclin D1 levels. Jurkat T cells treated with increasing concentrations of JS-K for 24 h were analyzed for total, cytosolic, and nuclear β-catenin expression by immunoblot of lysates (panel A, left side). Densitometry evaluation of levels of nuclear β-catenin and α-actin performed from three such immunoblots are shown in panel A, on the right side. *P < 0.01 compared to untreated controls. The protein levels of cyclin D1 were also reduced by JS-K (panel B, left) and as shown for three immunoblot evaluations in panel B, right. †P < 0.05 compared to untreated controls. Panel C shows that the reduction in nuclear β-catenin by JS-K was mediated by NO.

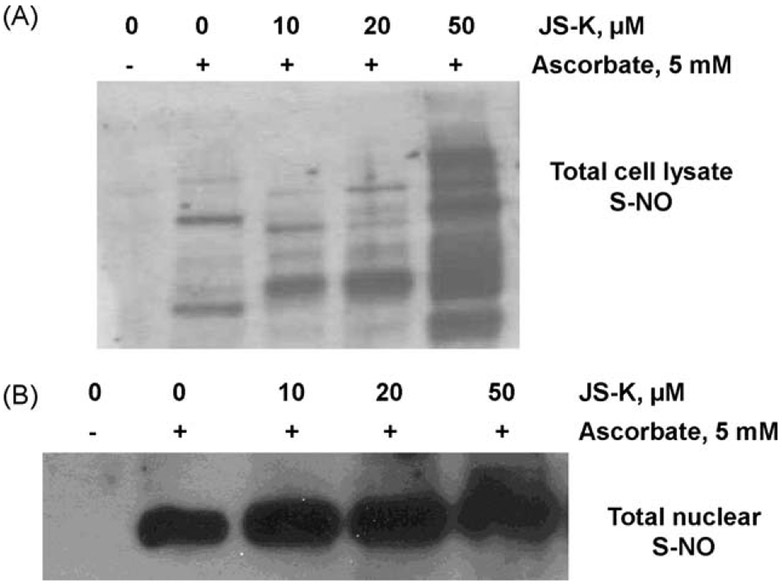

3.5. JS-K induces S-nitrosylation of nuclear proteins

Protein S-nitrosylation is a well-recognized reversible protein modification which has an important role both in normal physiology and in a broad spectrum of human diseases [26]. The ability of JS-K to induce S-nitrosylation of proteins was investigated using the biotin switch technique adapted from Jaffrey and Snyder [22]. In this assay, S-nitrosylated cysteine is switched for biotin, and visualized on non-reducing SDS-PAGE followed by anti-biotin-immunoblotting. Signals are representative of S-nitrosylated proteins.

As described in Section 2, omission of ascorbate in the biotin switch assay leads to nearly complete loss of biotinylation, resulting in no visible bands in the control samples (Fig. 8A, lane 1). In the presence of 5 mM ascorbate, total lysates from the untreated cells showed certain bands that indicate basal levels of S-nitrosylation of some proteins (Fig. 8A, lane 2). Increasing concentrations of JS-K S-nitrosylated several cellular proteins in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8A, lanes 3–5), indicating that JS-K induces modification of certain proteins. We further examined only the nuclear extracts from JS-K treated cells in order to determine if there is an overall increase in S-nitrosylation of nuclear proteins. Biotinylated proteins from nuclear extracts were separated from the samples by incubating with streptavidin beads, followed by elution of the biotin from the biotinylated proteins. The eluted biotin from samples was detected by anti-biotin immunoblotting representing total nuclear S-NO content. Fig. 8B shows that increasing concentrations of JS-K increased the total S-NO content of the nuclear proteins, suggesting an overall increased S-nitrosylation in the nucleus. At 50 μM JS-K, the % increase was 180 ± 12% compared to control cells (no JS-K in presence of ascorbate).

Fig. 8.

JS-K induces S-nitrosylation of nuclear proteins detected by the biotin switch assay (BSA). Panel A: In absence of ascorbate, the BSA leads to loss of biotinylation, resulting in no visible bands in the control samples (lane 1). In presence of ascorbate, total lysates from the untreated cells showed basal levels of S-nitrosylation of some proteins (lane 2). Increasing concentrations of JS-K (lanes 3–5) S-nitrosylated several cellular proteins in a dose-dependent manner. Panel B: Increasing concentrations of JS-K increased the total S-nitrosylated content of the nuclear proteins in a dose-dependent manner, at 50 μM JS-K, the % increase was 180 ± 12% compared to control cells (no JS-K in presence of ascorbate). Results are representative of two different experiments.

3.6. JS-K degrades β-catenin via NO release

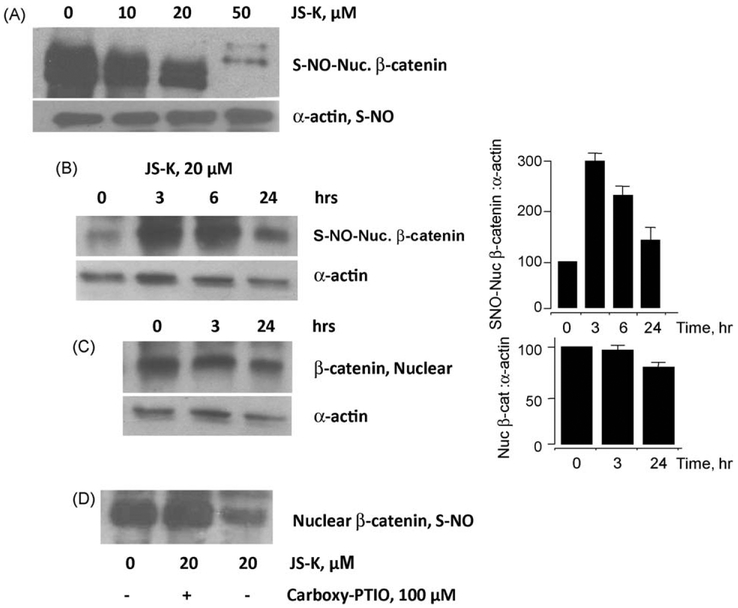

To ascertain whether the β-catenin protein can be modified by S-nitrosylation in situ, we treated Jurkat cells with JS-K at different concentrations followed by detection of S-nitrosylated nuclear β-catenin (S-NO-β-catenin) protein levels using the biotin switch method. At 24 h, increasing concentrations of JS-K led to S-nitrosylation of the nuclear β-catenin. However, there was a concentration-dependent degradation of nuclear β-catenin (Fig. 9A). In order to determine whether S-nitrosylation of nuclear β-catenin preceded the degradeation of the protein, we performed a time-course analysis for both S-nitrosylation of the nuclear β-catenin and its degradation. The results demonstrated that β-catenin as evaluated by the biotin switch method was S-nitrosylated in a time-dependent manner from 0 to 6 h, followed by its decrease at 24 h (Fig. 9B). A comparison of the S-nitrosylated nuclear β-catenin to the total nuclear β-catenin from the same extracts showed that β-catenin protein levels were unchanged from 0 to 3 h and then degraded at 24 h (Fig. 9C), whereas S-nitrosylation occurred earlier at 0–6 h (Fig. 9B). From this it may be concluded that S-nitrsolyation of nuclear β-catenin precedes its degradation. Finally, to confirm that nuclear β-catenin S-nitrosylation was indeed due to NO release, we used the NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO. Treatment of the cells for 24 h with 20 μM JS-K reduced the levels of nuclear S-NO-β-catenin, however, in presence of carboxy-PTIO this reduction was totally abrogated (Fig. 9D).

Fig. 9.

JS-K degrades nuclear β-catenin via NO release. JS-K degraded S-nitrosylated nuclear β-catenin in a concentration-dependent manner (panel A). The cytoplasmic levels of S-nitrosylated α-actin (Fig. 8A lower panel) were used as an internal control for the biotin switch assay, and were not altered by JS-K. Nuclear β-catenin was S-nitrosylated between 0 and 6 h (panel B), where as total nuclear β-catenin protein levels was degraded at 24 h (panel C). Pretreatment with carboxy-PTIO, reversed the effects of JS-K (panel D). Results are representative of two different experiments ± range.

4. Discussion

Nitric oxide and nitric oxide donors are known to induce cell apoptosis and differentiation [6,27,28]. JS-K is known to induce differentiation and apoptosis in human myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells [28]. Antineoplastic effects of JS-K have been reported in AML tumor models in mice. [6,9,12]. However, the mechanisms for the cell growth inhibitory effects of JS-K are not completely elucidated. HL-60 cells poorly express β-catenin whereas ALL Jurkat T cells express high levels of β-catenin [17]. Therefore, in the present study we evaluated the effects of JS-K on β-catenin in Jurkat T cells.

It has been shown that JS-K and its analogues inhibited the growth of various cultured human cancer cell lines such as lung (A549 and H441), colorectal (HCT-116 and HCT-15), ovarian (OVCAR-), and prostrate (PC-3); suggesting a tissue type-independent effect [13,29]. Among the leukemia cell lines, JS-K also inhibited HL-60 myeloid leukemia and U937 monocytic cell lines [29]. In this study we have extended these observations to include Jurkat acute T cell leukemia cell line. Our data show that JS-K dose-dependently inhibited the growth, induced apoptosis and produced a G2/M cell cycle arrest in Jurkat T cells. Furthermore, previous reports using other nitric oxide-releasing drugs have similarly demonstrated inhibition of proliferation of cancer cells via apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [30-32]. Considering the overall effect of JS-K, it may be inferred that there is inhibition of proliferation, and a combination of apoptosis and necrosis. For example, at 10 μM JS-K there was 40% cell death (LDH assay at 24 h), 50% inhibition of cell viability by MTT, and 16% apoptosis. This may imply that apoptosis and necrosis can occur simultaneously as reported by others [33].

It has been demonstrated that NO can mediate acute phase protein/gene induction and MAP kinase pathway activation [9-11,34,35]. To explore the molecular effects of NO in T-ALL cells, we analyzed whether JS-K could interfere with the Wnt pathway that plays an important role in the early stages of leukemia. In Jurkat T cells, the inhibition of catenin/TCF transcriptional activity ocuured with an IC50 of 3 ± 1.6 μM. Next we studied the effect of JS-K on β-catenin expression in Jurkat T cells. Decreases in the nuclear β-catenin level was observed in these cells. No major effect of JS-K could be observed on cytoplasmic β-catenin. The cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin remained high, and the total amounts of β-catenin appeared unchanged. This difference between nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin levels observed here may be explained by a recent report in which it was demonstrated that JS-K caused accumulation of cellular β-catenin by inhibition of proteosomal activity, known mostly to occur in the cytoplasm [36]. In particular, NO is also known to affect function of other ‘degrading enzymes’ through S-nitrosylation [37]. The inhibition of this signaling pathway by 10–20 μM JS-K, which was associated with reduced cyclin D1 expression, suggests that it may represent an important disruption mechanism in the carcinogenic process. The present study does not address what percentage of β-catenin protein is S-nitrosylated. If the degree of S-nitrosylation is low, then it is unlikely that it would have a major effect. The degree of S-nitrosylation and degradation of β-catenin is an ongoing study and we are currently trying to quantitate these.

Low concentrations of JS-K (2–20 μM) clearly have effects on transcription, cell cycle and apoptosis. While β-catenin/TCF-4 transcriptional activity was inhibited at very low concentrations below 10 μM, β-catenin degradation was not observed at these low concentrations. This may be explained by our past reports demonstrating the ‘dual effect’ of NO-releasing compounds, where at low concentrations disrupt β-catenin/TCF binding, and higher concentrations degrade β-catenin [38,39]. Further, the effects of low concentrations of JS-K (10–20 μM) on cycle block and apoptosis prior to appreciable β-catenin reduction (50 μM) is suggestive of pleotropic mechanisms that may contribute to the observed effects. Further, JS-K is reported to increase p53 and Hdm2 levels in RPE cells at 10 μM concentration [36]. In our previous studies on NO-donating compounds such as NO-aspirin, other molecules in addition to β-catenin such as NF-κB, COX-2 and iNOS were also targeted demonstrating pleotropic mechanisms.

It is increasingly accepted that S-nitrosylation of proteins serves as a critical cellular regulatory mechanism related to O-phosphorylation [40]. Further, S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues of β-catenin has been speculated to be a possible modification process by another NO-donating compound, nitro-aspirin, introducing steric hindrance to β-catenin/TCF interaction [38]. Such degradation of nuclear β-catenin by JS-K is clearly an NO-dependent effect, and we demonstrated that it is specifically S-nitrosylation which precedes the degradation. Direct evidence for the influence of β-catenin nitrosylation on its transcriptional activity and mechanism of degradation remains to be established. Regarding the observed degradation of β-catenin, caspases involvement is a possibility. JS-K has been reported to activate caspase-3 and caspase-9 in acute myeloid leukemia cell line HL-60 [41]. Further, our previous reports on NO-donating aspirin have demonstrated that β-catenin degradation occurs, in part, due to caspase activity [42]. We would like to speculate here from the current studies in Jurkat cells that caspases may be induced by JS-K due to S-nitrosylation of β-catenin. Although this may be a radical speculation, there is one very recent report suggesting that S-nitrosylated proteins induce apoptosis in tumor cells [43] even though anti-apoptotic effects of NO are common. This may be a possibility since high levels of NO are produced.

Recent data has indicated that β-catenin is required to maintain stem cells in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) which is a common acute leukemia in adults [44]. Researchers determined that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is important for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) survival only during fetal stages and not for renewal of adult HSCs. In this context, our study of a novel compound JS-K that inhibits β-catenin may have potential in suppression of leukemia and its recurrence.

In conclusion, JS-K has a direct and rapid effect on Wnt signaling; the effect of these changes on the many genes whose transcription depends on Wnt signaling contributes to the death of the cell. Our results suggest that JS-K inhibits the cell proliferation of Jurkat T leukemia cells by S-nitrosylation of nuclear β-catenin, degradation of nuclear β-catenin, and reduced expression of cyclin D1. These results provide strong laboratory evidence in support of JS-K for further evaluation in the treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and by NCI contract HHSN261200800001E.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:225–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Faderl S, Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Estrov Z. Clinical significance of cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 1998;91:3995–4019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stefano F, Distrutti E. Cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibiting nitric oxide donating (CINODs) drugs: a review of their current status. Curr Top Med Chem 2007;7:277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Li CQ, Wogan GN. Nitric oxide as a modulator of apoptosis. Cancer Lett 2005;226:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chung HT, Pae HO, Choi BM, Billiar TR, Kim YM. Nitric oxide as a bioregulator of apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001;282:1075–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shami PJ, Saavedra JE, Wang LY, Bonifant CL, Diwan BA, Singh SV, et al. JS-K, a glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide donor of the diazeniumdiolate class with potent antineoplastic activity. Mol Cancer Ther 2003;2:409–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shami PJ, Maciag AE, Eddington JK, Udupi V, Kosak KM, Saavedra JE, et al. JS-K, an arylating nitric oxide (NO) donor, has synergistic anti-leukemic activity with cytarabine (ARA-C). Leuk Res 2009;33:1525–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Keefer LK. Nitric oxide (NO)- and nitroxyl (HNO)-generating diazeniumdiolates (NONOates): emerging commercial opportunities. Curr Top Med Chem 2005;5:625–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ren Z, Kar S, Wang Z, Wang M, Saavedra JE, Carr BI. JS-K, a novel non-ionic diazeniumdiolate derivative, inhibits Hep 3B hepatoma cell growth and induces c-Jun phosphorylation via multiple MAP kinase pathways. J Cell Physiol 2003;197:426–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liu J, Li C, Qu W, Leslie E, Bonifant CL, Buzard GS, et al. Nitric oxide prodrugs and metallochemotherapeutics: JS-K and CB-3-100 enhance arsenic and cisplatin cytolethality by increasing cellular accumulation. Mol Cancer Ther 2004;3:709–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kiziltepe T, Hideshima T, Ishitsuka K, Ocio EM, Raje N, Catley L, et al. JS-K, a GST-activated nitric oxide generator, induces DNA double-strand breaks, activates DNA damage response pathways, and induces apoptosis in vitro and in vivo in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2007;110:709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shami PJ, Saavedra JE, Bonifant CL, Chu J, Udupi V, Malaviya S, et al. Antitumor activity of JS-K [O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl) 1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate] and related O2-aryl diazeniumdiolates in vitro and in vivo. J Med Chem 2006;49:4356–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chakrapani H, Kalathur RC, Maciag AE, Citro ML, Ji X, Keefer LK, et al. Synthesis, mechanistic studies, and anti-proliferative activity of glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide prodrugs. Bioorg Med Chem 2008;16:9764–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chung EJ, Hwang SG, Nguyen P, Lee S, Kim JS, Kim JW, et al. Regulation of leukemic cell adhesion, proliferation, and survival by beta-catenin. Blood 2002;100:982–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, et al. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:5522–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature 1999;398:422–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tsutsui J, Moriyama M,Arima N, Ohtsubo H,Tanaka H,Ozawa M. Expression of cadherin-catenin complexes in human leukemia cell lines. J Biochem 1996;120:1034–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stamler JS, Jaraki O, Osborne J, Simon DI, Keaney J, Vita J, et al. Nitric oxide circulates in mammalian plasma primarily as an S-nitroso adduct of serum albumin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:7674–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, Mullins ME, Jaraki O, Michel T, et al. S-nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:444–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saavedra JE, Srinivasan A, Bonifant CL, Chu J, Shanklin AP, Flippen-Anderson JL, et al. The secondary amine/nitric oxide complex ion R(2)N[N(O)NO](−) as nucleophile and leaving group in S9N)Ar reactions. J Org Chem 2001;66:3090–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Decker T, Lohmann-Matthes ML. A quick and simple method for the quantitation of lactate dehydrogenase release in measurements of cellular cytotoxicity and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activity. J Immunol Methods 1988;115:61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jaffrey SR, Snyder SH. The biotin switch method for the detection of S-nitrosylated proteins. Sci STKE 2001;2001:pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Li S, Whorton AR. Regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in intact cells by S-nitrosothiols. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003;410:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chattopadhyay M, Velazquez CA, Pruski A, Nia KV, Abdelatif K, Keefer LK, et al. Comparison between NO-ASA and NONO-ASA as safe anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic, anti-oxidant, prodrugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther (2010) doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.171017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lin SY, Xia W, Wang JC, Kwong KY, Spohn B, Wen Y, et al. Beta-catenin, a novel prognostic marker for breast cancer: its roles in cyclin D1 expression and cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:4262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med 2009;15:391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Magrinat G, Mason SN, Shami PJ, Weinberg JB. Nitric oxide modulation of human leukemia cell differentiation and gene expression. Blood 1992;80:1880–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shami PJ, Moore JO, Gockerman JP, Hathorn JW, Misukonis MA, Weinberg JB. Nitric oxide modulation of the growth and differentiation of freshly isolated acute non-lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leuk Res 1995;19:527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chakrapani H, Goodblatt MM, Udupi V, Malaviya S, Shami PJ, Keefer LK, et al. Synthesis and in vitro anti-leukemic activity of structural analogues of JS-K, an anti-cancer lead compound. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2008;18:950–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nath N, Vassell R, Chattopadhyay M, Kogan M, Kashfi K. Nitro-aspirin inhibits MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth: effects on COX-2 expression and Wnt/beta-catenin/TCF-4 signaling. Biochem Pharmacol 2009;78:1298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Royle JS, Ross JA, Ansell I, Bollina P, Tulloch DN, Habib FK. Nitric oxide donating nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer cell systems and human prostatic stroma via caspase-3. J Urol 2004;172:338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Mojic M, Malaponte G, Libra M, Cardile V, et al. Novel nitric oxide-donating compound (S,R)-3-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-5-isoxazole acetic acid-nitric oxide (GIT-27NO) induces p53 mediated apoptosis in human A375 melanoma cells. Nitric Oxide 2008;19:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Elmore S Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 2007;35:495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ridnour LA, Thomas DD, Donzelli S, Espey MG, Roberts DD, Wink DA, et al. The biphasic nature of nitric oxide responses in tumor biology. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006;8:1329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Roberts DD, Isenberg JS, Ridnour LA, Wink DA. Nitric oxide and its gatekeeper thrombospondin-1 in tumor angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:795–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kitagaki J, Yang Y, Saavedra JE, Colburn NH, Keefer LK, Perantoni AO. Nitric oxide prodrug JS-K inhibits ubiquitin E1 and kills tumor cells retaining wild-type p53. Oncogene 2009;28:619–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cordes CM, Bennett RG, Siford GL, Hamel FG. Nitric oxide inhibits insulin-degrading enzyme activity and function through S-nitrosylation. Biochem Pharmacol 2009;77:1064–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nath N, Kashfi K, Chen J, Rigas B. Nitric oxide-donating aspirin inhibits beta-catenin/T cell factor (TCF) signaling in SW480 colon cancer cells by disrupting the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF association. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:12584–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gao J, Liu X, Rigas B. Nitric oxide-donating aspirin induces apoptosis in human colon cancer cells through induction of oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:17207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lane P, Hao G, Gross SS. S-nitrosylation is emerging as a specific and fundamental posttranslational protein modification: head-to-head comparison with O-phosphorylation. Sci STKE 2001;2001:re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Udupi V, Yu M, Malaviya S, Saavedra JE, Shami PJ. JS-K, a nitric oxide prodrug, induces cytochrome c release and caspase activation in HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk Res 2006;30:1279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nath N, Labaze G, Rigas B, Kashfi K. NO-donating aspirin inhibits the growth of leukemic Jurkat cells and modulates beta-catenin expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;326:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Katayama N, Nakajou K, Ishima Y, Ikuta S, Yokoe J, Yoshida F, et al. Nitrosylated human serum albumin (SNO-HSA) induces apoptosis in tumor cells. Nitric Oxide 2010;22:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang Y, Krivtsov AV, Sinha AU, North TE, Goessling W, Feng Z, et al. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in AML. Science 2010;327:1650–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]