Abstract

Scientific articles have been traditionally written from single points of view. In contrast, new knowledge is derived strictly from a dialectical process, through interbreeding of partially disparate perspectives. Dialogues, therefore, present a more veritable form for representing the process behind knowledge creation. They are also less prone to dogmatically disseminate ideas than monologues, alongside raising awareness of the necessity for discussion and challenging of differing points of view, through which knowledge evolves. Here we celebrate 250 years since the discovery of the chemical identity of the inorganic component of bone in 1769 by Johan Gottlieb Gahn through one such imaginary dialogue between two seasoned researchers and aficionados of this material. We provide the statistics on ups and downs in the popularity of this material throughout the history and also discuss important achievements and challenges associated with it. The shadow of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is cast over the dialogue, acting as its frequent reference point and the guide. With this dialogue presented in the format of a play, we provide hope that conversational or dramaturgical compositions of scientific articles - albeit virtually prohibited from the scientific literature of the day - may become more pervasive in the future.

“At this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late!.. And we are blessed in this, that we happen to know the answer. Yes, in this immense confusion one thing alone is clear. We are waiting for Godot to come”

Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (Beckett 1953)

Deep down, science is a social question, a “worldwide proposition” (Zuckermann 1977), as it were, and the reasons for this are manifold. Scientific reasoning, for one, rests on the bed of unprovable premises. These foundations of rational thought cannot be unambiguously inferred using the logical apparatus, but rather present social conventions proven practical in a large number of empirical settings. Scientific observations could be validated or refuted on the bases of these premises, but these observations, in turn, cannot refute the elementary postulates. Euclid, in fact, the originator of the world’s most famous and oft-used of such postulates, a.k.a. axioms of the Euclidean geometry, never used the word Axiom. He rather spoke of κοινε εννοια (Euclidis 1888) - which literally translates to “common opinion” - and it was only Proklos and Aristotle that later redefined this term to “propositions that neither can nor need be proved” (Wiles 1983). Science perceived from the angle of the philosophy of pragmatism, in fact, becomes definable as a collection of communicable operations allowing humans to coordinate each other’s experiences toward implicitly or explicitly agreed goals (Winograd & Flores 1987), the broadest of which include survival, physical comfort and spiritual growth. One of the central motivations of scientific endeavors emerging from such a pragmatic perspective is that of discovering physical effects or inventing ways of controlling these effects for the benefit of fellow human beings. Love, along the way, becomes discoverable in the heart of the scientific enterprise (Uskoković 2012). Although the nurture of this socially oriented heart is rare in today’s academic coursework in natural sciences, in an ideal world it would be an integral element of education in hard sciences. In other words, analytics in it would be inextricably tied to arts, engineering to philosophy, technology to humanities, and so on.

Humans, after all, are social creatures and although social interaction is not necessary for learning to occur, it is essential for creating communicable skills, from which both humanity and the organisms attaining them will benefit. Values distilled through such interaction inconspicuously guide the creative efforts in science, whose extraordinary accomplishments have often fed on the insights from arts and humanities, let alone daily experiences and inspiration found therein (Uskoković 2014). Although the effects of such values are extraordinarily difficult to trace, the absence of evidence should not be confused here with the evidence of absence and their presence and effect on scientific creativity ought to be acknowledged as immanent, albeit subtle and elusive. This is not even to mention that for any scientific research to take place, funding must be obtained, which is a tedious process usually requiring the approval of assigned committees. In other words, society must find ideas valuable before they could be tested in reality, meaning that both the origins and the outcomes of scientific thought emanate from and merge into the social sphere, without which no such ideas would be possible or meaningful in the first place. Finally, the ecologists could now step in with the argument that there is no evolution but coevolution (Bateson 1972), implying that the interaction between organisms is an elementary unit of not only human civilization, but also the biosphere as a whole. All of this has been a prelude to the statement underlying the conception of a scientific review article in the form of a theatrical play: dialogues may be more natural to the exposition and elaboration of scientific ideas than monologues. Yet, the practice of composing and releasing scientific articles in such dialogical forms has been virtually nil to this day.

Of course, there are many ways in which dialogues could be fostered in scientific communication, including organizing round tables at conferences instead of amphitheatric lectures, appending online discussion forums to published articles, toppling the traditional academic hierarchies and substituting the principal investigator autocracy with enunciative egality, and so on. There is no doubt that many a Pandora’s box will be opened thereby, resulting in the dilution of the quality and focus of intimately individualized scientific visions and ideas. Such is the case, for example, with (inter)active learning, which benefits specific groups of learners, but diminishes the quality of the content covered in the classroom (Uskoković 2017), or with the links between research centers and funding agencies, which have become so tight today that the pure, basic science yielding fundamental and long-term benefits to the society often becomes openly depreciated in favor of applied research conducted with the goal of bringing benefits in shortest possible timespans (Tománek 2011). Dialogical scientific presentation, like the one presented here, is a shy step toward the collectivization of a domain that has been traditionally individualistic and all these potential demerits must be carefully considered and understood before this model of presentation becomes more pervasive. This presentation is also theatrical, drawing on the earlier ambitions to wed science and theater (Brecht 1955, Dürrenmatt 1964, Stoppard 1993, Djerassi & Hoffmann 2001, Djerassi 2012), satisfying along the way the authors’ aspirations to render science lyrical and inspirational, without compromising its rigor.

Lest it be a spoiler, this synopsis should mention some, but not all the details defining the backstory of the authors’ history in the subject treated theatrically in this piece. This history includes their running a lab specializing in research on hydroxyapatite, the material that will be in the center of the protagonists’ attention. Ironically, however, at the point of time in which this piece was written, this academic lab was not only one of the most scholarly productive ones in this particular research, but also usurped and closed, with the authors being exiled from academia. With their jobs lost, after a whole year of searching in vain for the next academic post, the idea of writing this piece came up. Penniless and broke, they now spend nights looking at the starry sky from their backyard, under a string of pink papelillos, a few pencil cacti and a giant eucalyptus and beside a squinted baby palm and an elfin mandarin. Their passion for research is immense, yet they have nowhere to run it and, even worse, all that they built over the years is now lying in ruins. Their dreams sink deeper and deeper with every breath of theirs, heavier and fuller of fears than they had known it to be. They shudder at the idea of what future, not enviable by any means, will bring and ruminate with wild bunnies, who are rustling the leaves under their feet, about what had led to their demise. Was it a wrongly chosen research in today’s scientific world where delving deep into traditional subjects with fresh eyes is rewarded less than jumping from one trendy bandwagon to another? Was it a curse and an impasse run into by being allured to the scientific charms of απαταω, whose identity will remain a mystery here – namely, whether it is a crystal, an alchemical distillation of it in the form of a corporeal spirit, a real-life person, a thaumaturge, a saver of dreamers ditched into social gutters, an inexplicably abstract concept uniting answers to the enigmas enfolding it and perplexing generations of its examiners, all of this together or something else will be left for the reader to muse over and unravel. Was it the excessive ambitions of the authors, whose setting the bars higher than the world must have frustrated the seekers of mediocrity, who have always comprised the social majority, and who did not think twice before giving them thumbs-down? Was it their scholastic nomadism and radically liberal philosophies of teaching and research that were perceived untrustworthy and at odds with the conservative administration of academic institutions? Was it the promiscuity of interests, the restless moving back and forth between science and arts and back, with frequent excursions into politics, that caused all of this? Was it their relentless experimentation with the form and inventive expressions of scientific concepts and ideas that implicitly denounced the dominant scientific practices and thus antagonized the authorities? Or was it something else, they wonder. And wonder continues. In light of this wonder the curtain lifts and the onstage dialogue begins.

(A familiar landscape. A tree and a stone. The sky is barren.)

VW: Nothing to be done.

VU: Indeed. The scientific community at large is beginning to come round to that opinion.

VW: What about us, as we sit on this crossroad?

VU: You know how it goes: “All my life, I have tried to put it from me, saying be reasonable, you have not tried everything”. There must be potentials that are still dormant and undiscovered in it, I have been telling to myself.

VW: And you resumed the struggle.

VU: And I resumed the struggle.

VW: I wonder if the things look any brighter in the biomedical sections of the scientific community.

VU: Slightly. But the excitement about it has been winding down steadily over the past decades.

VW: And the lackluster spirit of resignation has been taking over.

VU: Or contentment, that other, equally passive side of the coin of resignation (Crabb 2006).

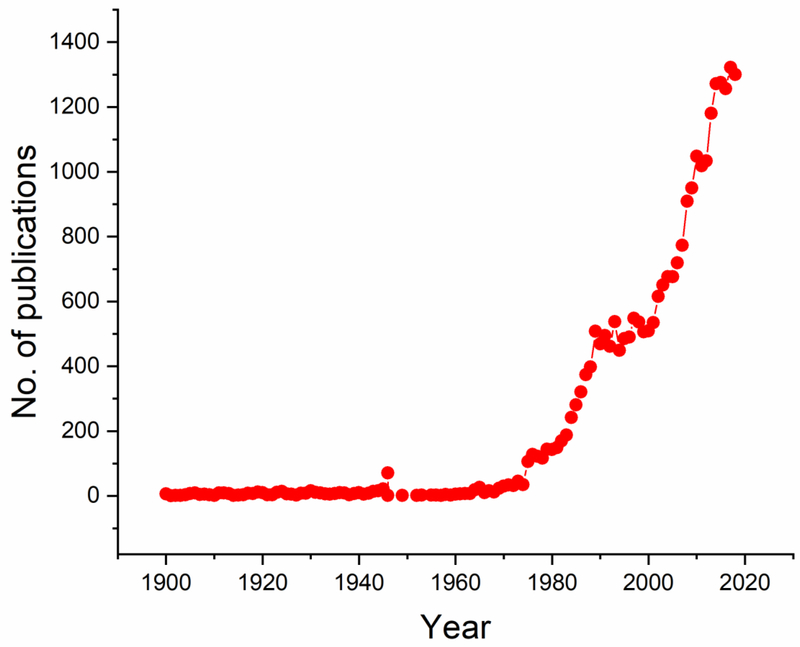

VW: Why is it then that the number of publications on it is constantly increasing? Look at the graph I have in my pocket (Fig.1).

Fig.1.

Total annual number of publications listed in the United States National Library of Medicine (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/, 12-3-2018) for years 1900 through 2018 and containing the keyword “hydroxyapatite”. Search was performed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ on December 3, 2018.

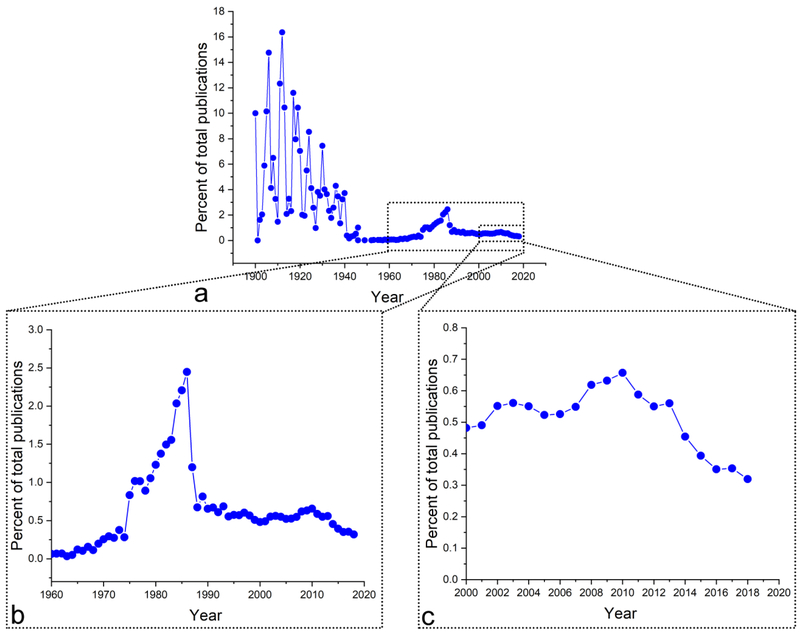

VU: This is a common misconception. The number of papers on almost any subject has been increasing in recent years because, simply, the global publication output has been increasing and is currently higher than ever in the history of scientific literature. If we were to normalize these numbers to the total number of scientific publications per year or, as I can plot it in Fig.2a, to the annual number of publications associated with the keyword “medicine”, the trend would not be ascending, but rather descending since 1900. In the pre-World War II period of the 20th Century, the technical papers on it would reach as high as 15 % of all medical studies for certain years, averaging at 5.23 ± 3.99 % (mean ± SD) for years 1900 through 1940. Then a drastic drop began, as poly(methyl-methacrylate), poly(ethylene) and stainless steel began to be used as bone substitutes, but the interest in it began to recover around the time the term “biomaterials” (Ratner et al. 2012) was coined at Clemson University symposia in the 1960s. Year 1975 was, however, the one in which the interest for it achieved a sudden renaissance. It was the year in which the first clinical study on it began and, coincidentally, the year the Society for Biomaterials was founded in. By 1980, the year in which the Biomaterials journal published its first issue, its first commercial product as a synthetic alternative to autogenic, allogenic and xenogeneic bone grafts entered the market. This Swiss product, Ceros, like its immediate successors in Europe and in the US, including ProOsteon, Replam, Interpore 200, Calcitite and Bio-Oss, were all granulated and the world had to wait until late 1990s for its first viscous product to be marketed (Campana et al. 2014). It came in the form of a self-setting cement, a decade or so after its discovery (Fukase et al. 1990). Its golden era became the 1980s, with its popularity, per Fig.2b, peaking in 1986, when 2.45 % of all medical publications had it play a usually main and very rarely supporting role. After this peak, the decline has been, more or less, steady, dropping to 0.48 % of total medical publications in 2000 and 0.32 % in 2018 (Fig.2c). Therefore, the interests in it have been winding down. It is a whole different story that the average impact of papers on it has been constantly getting lower. However, that is a subjective assessment and cannot be plotted except using vague criteria, such as journal impact factors, h-indices or similar.

Fig.2.

Percentage of publications listed in the United States National Library of Medicine (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/, 12-3-2018) for years 1900 through 2018 (a), 1960 through 2018 (b) and 2000 through 2018 (c), containing the keyword “hydroxyapatite” normalized to the total annual number of publications retrievable using the keyword “medicine”.

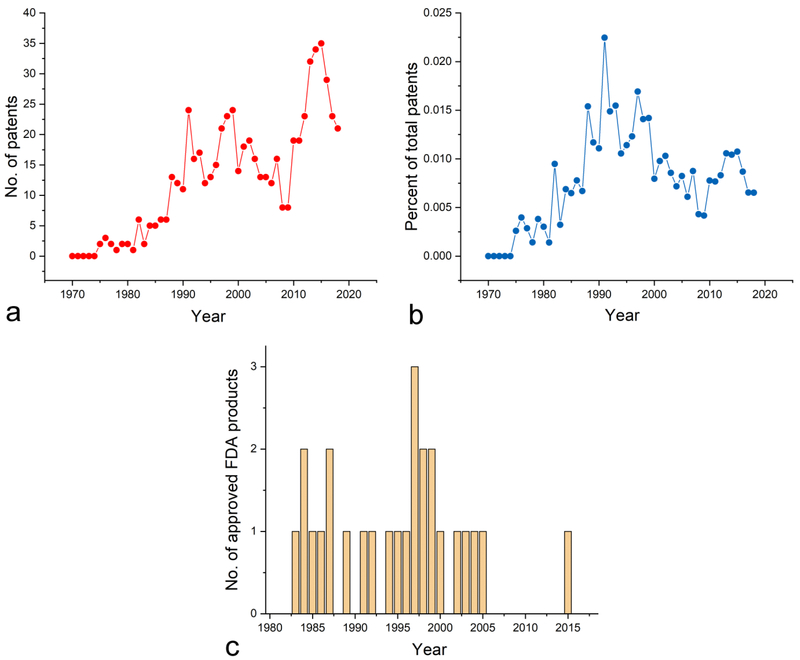

VW: Since you mention the commercial domain, I wonder if the trend in it is any different from that in basic sciences.

VU: Not at all, except for the expected delay in the peaking of this interest. Check out this other series of graphs I prepared (Fig.3). First, if you look at the total number of US patents on it over the years, you might again get the wrong impression that, notwithstanding the annual fluctuations and the drop in the first decade of the 21st Century, the interest for it in the industrial sector has been increasing since the 1970s. But once again, normalize these numbers to the total number of US patents and the trend is the same as that present in the scientific publication domain: peaking and then steadily descending from then on (Fig.3b). Unlike the academic interest peaking in 1986, the industrial interest peaked five years later, in 1991.

Fig.3.

Total number of US patents containing “hydroxyapatite” in their abstracts per annum (a) and the percentage of US patents containing “hydroxyapatite” in their abstracts normalized to the total number of US patents issued per annum (b). Annual number of medical devices bearing “hydroxyapatite” in their name and approved by the FDA (c). Search was performed on December 9, 2018 using the following databases: http://patft.uspto.gov/netahtml/PTO/search-adv.htm (a, b) and https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/SCRIPTS/cdrh/devicesatfda/index.cfm (c).

VW: Everything afterwards has been a steady drop.

VU: Finally, if you wonder about the FDA approvals of medical devices, the data demonstrate a peak in 1997, 8 years after the peak in the filed patent cases (Fig.3c). But then again, there is this giant hole spanning from 2006 to 2014, during which no medical devices containing it in their names were approved by the FDA.

VW: Commerciality. Is that supposed to guide us?

VU: By no means.

VW: I thought that we were the heralds of New Romanticism in science.

VU: Of returns to the purity of doing science that is independent of any monetary considerations in today’s increasingly corporate academia. Of looking down on patents with the same epic arrogance that was in the look of Jonas Salk when he uttered that famous remark: “Can you patent the Sun”?

VW: Of mind over matter and marvel over mercantilism.

VU: Hence we try to save it from this fall into oblivion and restore it in a fresh new light. Alas, the feeling is that we have slumped into some dark chasms with it too.

VW: Without anyone handing us the rope to lift us up.

VU: Who would do it anyway? The scientific elites who have wholly forgotten it? Corporate academicians who see it all through the prism of popularity and look down upon it as being old-hat and antique? Or the less eminent minds who still work on it, but do so, on average, in rather unimaginative ways?

VW: Truly, the impression of a literature junkie is that, notable exceptions aside, research on it has not strived to produce anything significantly new in recent decades. The most common approach in the biomedical realm is that of doping it in search of new properties (Ratnayake et al. 2017). However, one such methodology is not very innovative and does not answer anything downstream. It lacks fundamental insights and yet produces engineering concepts with little promise of translation and real-life applicability. It is an answer that neither arises from bold questions nor produces such questions in its wake.

VU: What a pity. It once used to be the subject of state-of-the-art research in biomaterials. Now it can hardly get to the most prestigious biomaterials journals. Even imaginative research on it is rejected with the premise that it is trite and clichéd by default.

VW: Add to that the abysmal career prospect of junior investigators whose prime research is on it and it only. It is considered as out of place in a bioengineering field as washed-out plimsolls on a prom night.

VU: Yes, we need not look farther than us. Jobless, broke, spending the night in a ditch.

VW: Beaten too.

VU: Certainly they beat me.

VW: Shouldn’t we be mad?

VU: Livid we are. But also festive.

VW: And wretched.

VU: And anxious. And blessed too. Every emotion under this hatful of hollow we harbor in our hearts.

VW: But hearts we have not lost.

VU: Let me read this: “What is good of losing it now. We should have thought of it million years ago, in the nineties”, when we began this whole academia gig. Now it is too late. This ball must keep on rolling.

VW: To the street?

VU: To the street (Tunstall 2004), if need be.

VW: I think that we have nothing more to do here. For me it is over and done with.

VU: This is why we are here, under this somber firmament. To discuss whether it has anything else to bestow. Or its story has been exhausted and we should close the shop and go bowling.

VW: Stars are out.

VU: And wisterias are hanging from the verandah.

VW: Mellifluous smell of this strange fruit is in the air too.

VU: And canopies begin to tremble in the breeze.

VW: Before we lope along, perhaps we should muse a little longer on its real identity.

VU: We can call it απαταω, by its etymological core name. Remember how the 18th Century mineralogists confused it with a number of other minerals because of its coming in many different colors, lusters and feels. Oftentimes it was confused with precious gems, but then a drop of lime would dissolve it, meaning that it was not so precious in the end. The geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner is credited with christening it in 1788 using a variation of this term, απαταω, meaning “decipio” in Latin or “to deceive” in English (Roycroft & Cuypers 2015).

VW: Even he got misled.

VU: Well, what he classified as apatite was reclassified as fluorapatite 72 years later by Karl Friedrich August Rammelsberg. Nonetheless, its earliest mention dates almost two more decades back in time, specifically to 1769, when, according to Roscoe and Schorlemmer (Roscoe and Schorlemmer 1881), Johan Gottlieb Gahn discovered it in bones and Carl Wilhelm Scheele described it in a 1771 publication (Dorozhkin 2013).

VW: Then came synthesis and application.

VU: In the biomaterials universe, the attempts to apply have traditionally preceded the attempts to understand or create. Hence, it should not surprise us that rickets and other diseases tried to be cured with it already in the 18th Century. A couple of synthetic methods were compiled by Aikin & Aikin in 1807 (Aikin & Aikin 1807), but the world had to wait for 40 more years for the first solubility tests to be reported (Lassaigne 1847). Meanwhile, Philipp Franz von Walther replaced parts of the skull with it in 1821 (von Walter 1821). In 1881, William Macewen replaced the infected humerus of a four-year-old Scottish boy with it (Macewen 1881), but these were all natural derivatives. In synthetic form, it was first implanted in rabbits in 1920 (Albee 1920). In 1930, its crystal structure was elucidated (Mehmel 1930, Náray-Szabó 1930), and the rest is history (Eliaz & Metoki 2017).

VW: But why is it so special?

VU: It isn’t. That’s what makes it so special.

VW: It lies somewhere in the middle of the Mohs scale.

VU: It defines number 5, the exact midpoint of this scale, given that it is neither too soft nor too hard.

VW: Lukewarm it is?

VU: Pleiotropic, protean or promiscuous, if you will, may be better words to describe it. In a way, it resembles carbon, which is, likewise, a middle way entity. As a chemical element, neither is it too electrophilic nor too nucleophilic, being positioned right in the center of the Periodic Table.

VW: Both carbon and it form the backbones of life.

VU: This midstream nature is indeed the reason for its specialness.

VW: Mundaneness that turns into extraordinariness. A low-key hero, unpretentious, but indispensable.

VU: Hence its comparison with the ugly duckling (Uskoković & Desai 2013a), the one who transforms into a white swan by the end of the fairytale.

VW: And with Frodo Baggins too.

VU: Yes, that funny, timid hobbit that everybody ridiculed when Gandalf the Grey proposed they should take him on a mission to Mount Doom, along with other martyrs (Tolkien 1954).

VW: It, itself, is kind of grey too.

VU: Pale, greyish, lacking any luster in the pure form. Being neither a conductor of electricity nor exhibiting any level of magnetic attraction. Interesting electromagnetic properties, such as piezoelectricity (Nakamura et al. 2012), ferroelectricity (Lang et al. 2013), pyroelectricity (Tofail et al. 2009) and conductivity to protons (Maiti & Freund 1981), it either has only in traces or at levels that are not competitive with other materials. Its mechanical properties are also rather poor if we discount for the solid compressive strength of its sintered blocks (van Lieshout et al. 2011).

VW: And yet it gives bones their strength.

VU: Despite all these weaknesses, it presents the evolutionary choice for the mineral component of bone (Zimmermann & Ritchie 2015). Out of thousands of minerals found in Earth’s crust, it is the one that the skeleton, the foundations of the bodies of us and other vertebrates ended up being predominantly made of.

VW: So what is its secret?

VU: That is what we have been trying to reveal. Perhaps we can see into the future. Or, the past, which is the same thing. As Marshall McLuhan said, “we march backward into the future” (Coupland 2010). Future can be seen only by looking at the rearview mirror.

VW: This would make future in our views factual, not fictive.

VU: Not really, given that any interpretation of historic events is somewhat fictive.

VW: Our characters here are somewhat fictive too.

VU: Mine ain’t.

VW: Anyway, two hundred and fifty years it has been when we talk about this past, you say.

VU: Yes, though the specific time of discovery is rather blurred and stretched, impossible to pinpoint with precision, like most historic events of this kind. Also, this quarter of the millennium includes the periods of mere elucidation of its composition and structure. Only the last 100 years mark the period of investigation into its practical application and optimization for it.

VW: And this optimization has not been very systematic at all times.

VU: It has not. For example, virtually all of its formulations for bone replacement have been either monophasic or biphasic, even though it exists in about a dozen different stoichiometric formulas (Dorozhkin 2009). Also, the addition of ions to modify its properties has rarely been done within a broad range of dopant concentrations and with the combination of (i) systematic variations in synthesis parameters; (ii) state-of-the-art physicochemical characterization, (iii) computational modeling, and (iv) biological response analyses. Studies combining all of these into single approaches, where each of these elements would build a single analytical framework, have been very rare. Yet, this is not to say that the field is not populated with various wonderful studies on it.

VW: But the angles of study have been limited and not cross-disciplinary enough.

VU: Well, that is the problem plaguing today’s science in general. How do we make people comfortable to reach out to languages that are barely comprehensible to them and combine them with theirs? It is a tough challenge. Another problem are resources.

VW: Resources?

VU: It has traditionally been a poor man’s material. And amongst the poor, resources are scarce. Yet, you need large, well-funded projects to build broad enough of a research network.

VW: On the other hand, scarcity of resources has been the driver of collaboration all throughout the ages. Think of the experiments on bacteria that showed that overabundance instigates self-interested, competitive behavior, while scarcity leads to cooperative and even self-sacrificial acts for the benefit of the whole spore (Farley 2012).

VU: Add to that the study where 90 % of archaea isolated from the Siberian permafrost survived after being exposed to the simulated Martian environment, as opposed to only 3 % of the same organisms isolated from warmer and more comfortable habitats (Morozova et al. 2007). This may also be explainable by the more developed quorum sensing in organisms from harsher natural settings.

VW: There is also the Snowball Earth hypothesis per which the decimation of the population of species due to harsh environmental conditions increases the average relatedness between any two individuals and, thus, the level of altruism among the species’ members (Boyle et al. 2007).

VU: Indeed. The post-glaciation population boom caused enough evolutionary pressure to exceed the reproductive cost of forming the first complex animal. This hints at stress due to adversities as more often a friend than a foe in the evolution of higher forms of life. To be deprived of resources can be a greater spur for creative thought. One can no longer rely on expensive equipment and armies of well-paid workers. Rather, one has to compensate for the missing resources with creative ideas.

VW: And when the material is poor, it must instruct its handler to treat it with an equal level of ease and minimalism in mind.

VW: Its syntheses are easy. And inexpensive too.

VU: Place it side by side with typical polymers used in tissue engineering and you will see a tremendous difference in price. Its frequent polymeric companion, poly(lactide-co-glycolide) is more than 1,000 times more expensive on the market as a raw chemical ingredient (Uskoković & Wu 2016). For a polymer such as hyaluronic acid, this difference reaches almost 500,000. When you add the cost of particle structure optimization to this, this difference becomes even greater.

VW: And then there is the “nano” feasibility argument.

VU: Yes. Unlike polymers, which are rather difficult to synthesize in the nanostructured form, one has to try hard not to synthesize απαταω as nanoparticles. From bone to dentin to enamel, it is strictly found in the form of nanoparticles. And if even extremely low supersaturations and surface-controlled conditions under which biomineralization proceeds yield nanoparticles, they would also be the natural products of more abrupt precipitation reactions, such as those routinely performed in the lab.

VU: It indeed has a great lesson to teach us, namely the finding of richness in scarcity.

VW: It is a profound lesson to learn.

VU: Relevant to science, but also life.

VW: It teaches empirical simplicity. And need I add that low cost, easy regulatory approvals, synthetic reproducibility and low risk of adverse events accompanying this simplicity are all appealing to the clinic and the market?

VU: Instead of striving to make things that are ever more compositionally and structurally complex, it tells us that great rewards come from making things simpler.

VW: How many people in the field actually understand this?

VU: Not many, in my opinion. The usual idea is that this is some sort of return to the primitive age, where we would blend its pastes by hand and flinging them into open bone voids, like snowballs.

VW: Here comes Ozu.

VU: One could hardly hear the footsteps.

VW: Just a silhouette smeared over the horizon.

VU: Isn’t that Pozzo? Pozzo and Lucky? I swear I could tell apart Pozzo’s whip and the rope tied around Lucky’s neck for a moment. Moving like a caravan over distant desert dunes.

VW: Just a Fata Morgana. That is what it is. These two oddballs and other symbols of despotism and passive servitude that pervade today’s academia are far removed from us. Neither do they care about us nor we about them. It is rather Ozu, the most Japanese of all Japanese filmmakers, approaching us inconspicuously, like a ghost.

VU: Or a nuclear shadow expanding over this wall.

VW: His story is very instructive.

VU: Yes. The more funds he had to make his films, the less budget he used to make them, as they were deliberately becoming more simplistic in storyline, scenography, dialogue and camera movement.

VW: And they were becoming more beautiful to watch too.

VU: Certainly. They epitomize the aesthetics of poverty at its best in this medium.

VW: But how do we reconcile this intrinsic simplicity, cheapness as it were, with the extraordinary pleiotropic nature of απαταω?

VU: Given its protean character, there will be numerous levels at which this simplicity and complexity will flow to and from one another, like the opposite colors in the circular Tai-Chi symbol.

VW: A mysterious material it is.

VU: A material? It is as mysterious as the town of Twin Peaks. Dull at first, the more you look at it, the more you become intrigued and drawn into the mysteries that abound in it.

VW: I am curious to see what it has to offer. But mysteries mean that there is a lot of things that we do not understand about it.

VU: Hence the idea that it should be crowned the prince of peculiarities in the domain of solids, to complement water as the princess of peculiarities in the realm of liquids (Uskoković 2015b). Think, for example, of its highly diffusive and hydrated surface, forming almost a continuum at the solid/liquid interface. It is the key to its unusually adaptive surface (Cazalbou et al. 2004), capable of swiftly adjusting structure to its immediate chemical environment. One practical downside of this surface diffusivity and the rapid exchange of ions across the solid/liquid interface is the virtual impossibility of stable chemical conjugation of organic ligands to it.

VW: Or the fuzzy transition between amorphous and crystalline states?

VU: Yes. Its crystallization proceeds through an unusually complex series of nucleation, aggregation, coalescence and growth processes (Niederberger & Cölfen 2006). The properties, including the biological ones (Wu & Uskoković 2017), drastically change if the system is frozen in one of these intermediate, metastable states.

VW: Is this where its comet tail comes into play?

VU: Possibly. To visualize it, we should remember that very fine, 9 Å sized prenucleation complexes, occupying a transitional state between the liquid and the solid state, are the first to form during its crystallization. Because every solid/liquid interface implies a finite exchange of ions between the two phases, these clusters are expected to constantly surround it when it is dispersed in an aqueous environment, forming a sort of dense hydrodynamic cloud of ions, clusters and ultrafine nanoparticles around it. The effects of this strange aureole, or “comet tail”, as you call it, are largely unknown, but must be intense. After all, this comet tail must be longer and denser around it than around most other oxide particles, simply because of its structural inclusion of hydroxyl groups, which form a continuum with an aqueous medium across the solid/liquid interface.

VW: The ability to accommodate both cations and anions internally or undergo ion exchange with most elements of the Periodic Table (Wopenka & Pasteris 2005) is pretty fascinating too.

VU: Remember that this extraordinary structural flexibility comes in a ionic crystal containing high valence states, specifically +2 and −3, along with −1, where relatively low tolerance to defects, bond angle change and lattice strain could be expected. Add to this the enigma of relatively high nucleation rate even at very low supersaturations and relatively low crystal growth rate even at very high supersaturations, and a plethora of other effects.

VW: Yet, isn’t the fate of all mysteries to be neglected in an answer-idolizing world?

VU: It is. People do not know how to react in front of the mystery of being and their usual reaction to it is discomfort and the raising of a guard.

VW: Or turning away from it.

VU: And walking away.

VW: But we must continue to wait.

VU: And do nothing.

VW: Science needs it. This staring at the ceiling. And quietly reflecting.

VU: Everything is indeed done so fast these days.

VW: It is a cutthroat race out there. A relentless rush forward propelled by the thirst for stardom, for fame, for financial rewards and whatever else being credited for the discovery of something brings about.

VU: That is how science loses its soul.

VW: And style too.

VU: But without this looking back… won’t we not know where we are heading to?

VW: We won’t. And may fall into a pit.

VU: And yet, creativity requires time to flourish. So we slow things down in hope of coming face to face with it and capturing its essence.

VW: Shhh. So quiet in here.

VU: It is as if we could hear the silent hum of the Earth spinning in space.

VW: And we continue to wait.

VU: Wait?

VW: Wait for απαταω, to save the world.

VU: Like the little cloud hovering above our heads?

VW: In the zenith it is.

VU: But it is in crisis too, perhaps shoved into the ditch, just as we are. Flies may be buzzing around its eyes and the idiot wind blowing through its flowers (Dylan 1975), just as they buzz and blow around here.

VW: In crisis?

VU: Yes, once every other biomaterial scientist’s favorite, it has fallen out of favor in the battle against polymeric constructs in the recent decades. It is impossible to process using 3D printing or other forms of rapid prototyping without appropriate additives (Seitz et al. 2005); its cohesion degree and integrity are lesser, especially when it comes to complex construct geometries; its flexibility is lesser too; the capacity to engrain and retain complex macroporous patterns minimal. Compare it with a polymer, such as polyurethane, which can be tuned to display a broad range of properties, from biodegradability to extreme stability, by controlling the ratio between the hard and soft segments (Gogolewski & Gorna 2007), yielding excellent effects on bone regeneration thereby. It neither has the resistance to wear and capacity to be used for load-bearing applications, as metals do. Offer the orthopedists the idea of implanting it and it only into the body, and they might ridicule both you and “the stone” as they often call it these days (Habraken et al. 2016).

VW: Hence the reduction of its usage to only the bioactive additives, osteoconductive components and reinforces of polymeric constructs and scaffolds (Xie et al. 2018, Narayan et al. 2017, Manda et al. 2018).

VU: Even then, there are questions. One of the unanswered ones is its interaction with collagen. We know that it is critical for the magnificent properties of bone (Stock 2015). And while we have made strides in understanding this interaction at the atomic scale (Uskoković & Bertassoni 2010), we are still far from replicating it in the lab. This, of course, constitutes a general problem in biomimetics – namely, many of the superb natural material structures are now elucidated down to their finest scales, but understanding and mimicking their biosynthesis are still unaccomplished. This goes along with the greater interest of today’s materials science in elucidating structures than processes (Basic Energy Sciences Advisory Committee 2015). Yet without creating the most optimal interaction at the atomic scale, its combinations with polymers will never live to their fullest potentials. Until we solve this problem, we will not be able to fabricate a material with the same mechanical properties, metabolism and intrinsic cellular activity as bone.

VW: Deep down, a supporting role it is.

VU: I wonder if it pays any heed to this downgrading thereof from the main to the supporting role in our sciences. It still plays a major one in Nature.

VW: The essential doesn’t change.

VU: On the other hand, its application repertoire is immense. It is used in a number of industries. We talk about environmental remediation, nuclear waste and chemical separation industries, where its superb adsorption properties are harnessed to isolate toxic metals (Oliva et al. 2011), radionuclides (Rigali et al. 2016) and organic contaminants (Liu et al. 2017), but also antibodies (Guerrier et al. 2001), nucleic acids (Giovannini & Freitag 2001) and viruses (Saito et al. 2013); energy sector, where it is used as a catalyst for fuel production (Essamlali et al. 2017); agriculture, where it is used in superphosphate fertilizers (Xiong et al. 2018); the food industry, where it is used as a leavening agent and dietary supplement (Benjakul 2017); cosmetics, where it acts as an agent for controlling abrasion, bulking and opacity (Epple 2018). It has also been used in the second-generation fluorescent tube phosphors thanks to its ability to be doped with combinations of luminescent transition metals, rare earth elements and anion impurity activators and co-activators (Moran et al. 1992). Its elementary building block, a.k.a. Posner’s cluster has been even recently proposed as a neural qubit for quantum entanglement and 31P spin computing in the brain (Swift et al. 2018, Player & Hore 2018).

VW: Last but not least, there is the biomedical field.

VU: Specifically orthopedics and dentistry, where it has been a traditional choice for boney tissue substitutes thanks to the old Latin medical motto: “Similia similibus curentur” (Uskoković 2015a). Self-setting bone cements (Fosca et al. 2012), dental remineralization agents (Juntavee et al. 2018), anti-sensitivity additives in tooth whitening procedures (Mehta et al. 2018), reinforcement components of tissue engineering constructs (Uskoković 2015c), bioactive coatings on bioinert metallic (Ahn et al. 2018), ceramic (Gryshkov et al. 2016) and polymeric (Johansson et al. 2018) implants, but also non-viral gene delivery carriers (Do et al. 2012) and bulking agents for the treatment of urinary incontinence (Eftekharzadeh et al. 2017) are some of its applications.

VW: Hence, its potentials must be immense.

VU: So do we believe. They stem from an extraordinary crystallographic, stoichiometric and structural complexity that it holds within. Its cation is the epitome of chaotropic properties and its anion stands on the opposite side of the spectrum, being one of the most kosmotropic, that is, order-bearing ones (Kunz 2010). And then there are hydroxyl groups traversing the screw axis of the unit cell basal planes in threads, defining with their symmetry whether the space group of the material is monoclinic or hexagonal (Suda et al. 1995), but also governing a range of physicochemical properties. This triad of ions, two of which are antipodes of one another and the third one of which can be a link between these two, is a guarantee for a very crazy party, if we were to refer to Andy Warhol’s adage: “One’s company, two’s a crowd and three’s a party” (Dennick & Spencer 2011).

VW: Aren’t all these things that we do not precisely understand, things that are enigmatic in it, actually keys to the discovery of great functional properties in it?

VU: Indeed they are. There are all signs that there is more to the picture than meets the eye.

VW: And when people deny it for its potentials, it should be similar to blaming on one’s boots the faults of one’s feet. That is, mediocre properties may be assigned to it solely due to the lack of creativity in scrutinizing and utilizing it.

VU: Nature certainly has made good use of it, so why can’t we?

VW: Our work in the recent years revealed a number of its properties never reported before, in which sense it also proved that there are lots of interesting effects waiting to be discovered in it.

VU: We found out that its chemical composition can be used as a control parameter for tuning the drug release rate (Uskoković & Desai 2013b). Aggregation phenomena can make this release sustainable, lasting for months if needed. Then we showed for the first time that the kinetics of its formation can be used to control the drug release kinetics (Ghosh et al. 2016). We discovered the memory effects governing its recrystallization and further demonstrated that this memory affects the biological response (Uskoković et al. 2018). Then we discovered oscillatory, nonlinear phenomena in the hardening reaction of its self-setting pastes (Uskoković & Rau 2017).

VW: What about its intrinsic antibacterial effect (Wu et al. 2018), my favorite? And the synergy it engages in with antibiotics to activate even antibiotics no longer active against specific multidrug-resistant bacterial species?

VU: Then there is its ability to act as a vehicle for carrying superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles into cells (Pernal et al. 2017) and helping them reverse the negative uptake selectivity, where these nanoparticles, delivered alone, enter primary cells much more efficiently than the cancer cells?

VW: Its uptake propensities are quite fascinating when you think about it.

VU: Yes, they exceed even those of cationic vesicles or aminated polymeric particles (Ignjatović et al. 2018). The potential of this easy internalization by pretty much all cell types is promising for a number of applications. For example, it can carry the antibiotics into the infected cells and reduce the number of intracellular bacterial colonies (Uskoković and Desai 2014).

VW: Add to that the endosomal escape capacity (Khan et al. 2016).

VU: It makes it a smart intracellular delivery carrier, a highly sought property for today’s advanced pharmacotherapies. Creating this smart response in the lysosome usually involves all kinds of synthetic sorcery in polymers, yet it is completely natural to απαταω.

VW: And all of these findings we came upon in a couple of years only. Three, to be more specific. How much more is out there?

VU: Nobody knows.

VW: Maybe it has all been but a tip of an iceberg so far.

VU: In a way, all these findings speak to the researchers that full stop is not to be placed to its story. It cannot be over yet.

VW: Many more effects are out there, waiting to be excavated.

VU: For example, its intriguing antibacterial activity could be further optimized through playing with materials chemistry and varying parameters such as particle chemistry, size, shape, surface charge, termination, complexation, etc.

VW: We might even recreate nanobacteria that way?

VU: Yes, given that it is the core component of these elusive self-replicating entities (Raoult et al. 2008, Young et al. 2009), which may be inanimate, but are incredibly biologically potent (Zhang et al. 2014).

VW: Then there is the unexplored addition of it to liposomal formulations and other vesicles, in analogy to the role it plays in casein micelles in milk (Lenton et al. 2015).

VU: The interaction with cholesterol seems pretty exciting too. Remember how there is the epitaxial precipitation of cholesterol on top of it and vice versa taking place during the formation of atherosclerotic deposits in blood because of the close match between the crystal lattice parameters of the two (Craven 1976)?

VW: Wait, should we speak loudly about those? Someone may hear and scoop them.

VU: I would rather us not being petty. Science is an endeavor on behalf of the whole humanity and we should share our ideas freely with everyone. Who knows, someone may pick them and make them even more beautiful. And workable too.

VW: It will be a win for us too.

VU: That reminds me of a story.

VW: And your “that reminds me of a story” reminds me now of the exact same words that fleshed on the computer screen in the story you often told about a computer the exact moment it became human: “That reminds me of a story” (Bateson 1979).

VU: Talk about the feedback loops and circular casualness of which we are made.

VW: And arcs in each good storytelling.

VU: Through storytelling, after all, is how we humanize our thoughts.

VW: Is this why we are exposing these ideas through this dialogue?

VU: It is only one of many reasons. For one, it may draw the reader into the subject, the way good storytelling does. Also, dialogues faithfully represent the dialectical synthesis of new knowledge. Even when we think alone, the arrival at new ideas is conditioned by the confrontation of two voices, one of which is prescriptive and the other one of which is partially antithetic. Finally, in the spirit of conceptual arts, an innovative form of expression is as important as its structural semantics. Here we experiment with the scientific article, albeit a critical review, in the form of a play. We are conceptual scientists, after all. In the world of increasingly industrialized and corporate academic research, it is an essential stand for an academic lab to take if it aspires to restore purity and romanticism in the heart of modern science.

VW: Yet, “a diversion comes along and what do we do? We let it go to waste”. Isn’t such a perspective that the scientific community will take in response to this innovative form?

VU: Yes, it is an unfortunate irony that science can evolve only by creating a difference in the fabric of knowledge, yet the making of differences is precisely prohibited and stood in the way of by today’s paradigmatic herds to whom bandwagon jumping is a cult and by whom intellectual subversion is as harshly prosecuted as witches in the Dark Ages. It is a paradox that the systematic neglect of philosophical and sociological courses from the increasingly linearized, solely skill-earning education in hard sciences can be blamed for. We are raising generations of scientists that are philosophically illiterate and this will have ever more devastating consequences in the pursuit of new knowledge.

VW: Habit is a great deadener at the end of the day.

VU: It is, but if being experimentative and innovative lies at the heart of your profession, you should be immune to it.

VW: So where do we go from here?

VU: Where do we go from here.

VW: We have to come back tomorrow.

VU: What for?

VW: To wait for απαταω.

VU: Alas, he did not come.

VW: It is all but exhausted, the way it seems. There is so much room for discovery and innovation – that should be the conclusion of our talk.

VU: Yes, but can it compete with polymers in scaffolds? With graphene among sorbents? With alloys among load-bearing bone substitutes? With silver among inorganic antimicrobials? Can it be utilized without a stable chemical conjugation capacity? What is its future amidst a poor colloidal stability without additives? Can it compete with trends? Is it powerful enough to swim against the stream? Or it well get lost in it.

VW: And we will never find it.

VU: Nor ourselves through it.

VW: Indeed.

VU: And if it comes? If it shows off its secret side, full of splendor? And the scientific community admits to its immense scientific potential?

VW: We’ll be saved.

Acknowledgments

National Institutes of Health award R00-DE021416 is acknowledged for support. Quoted phrases and many of the nonquoted lines originate from the English version of Waiting for Godot (Ref.1). The authors thank Sergey Dorozhkin for persuading us that the 250th anniversary ought to be celebrated and all the peers who have been supportive of our attempt to bring new life into research on this fascinating material in the recent years.

Biographies

Victoria Wu was a visiting professor and research scientist in various academic institutions, including Northwestern University, University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), Stanford University, University of Illinois in Chicago (UIC), and Chapman University. She is the co-founder and the principal manager for the Advanced Materials and Nanobiotechnology Laboratory (AMNL) directed by Dr. Uskoković. Together they published over a dozen peer-reviewed papers on hydroxyapatite and other calcium phosphates. Dr. Wu specializes in molecular biology analytics and education for the underprivileged.

Vuk Uskoković was appointed assistant professor of bioengineering at UIC in 2013 and of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences at Chapman University in Orange County, California in 2016. His former affiliations include various departments at UCSF, Clarkson University at Potsdam, New York, Jožef Stefan Institute in Ljubljana, Slovenia, and the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. He is the founder and the director of AMNL, whose goal is the development of nanotechnological innovations in the field of biomedicine. Under the guidance of Dr. Uskoković, AMNL trains a new generation of scientists capable of approaching state-of-the-art research with imagination and creativity, while also boldly questioning the modern science climate and mainstream practices. Alongside numerous books, book chapters and conference proceedings, Dr. Uskoković authored over 100 professional peer-reviewed papers, including over 40 on various aspects of the chemistry of hydroxyapatite and other calcium phosphates. Albeit rooted in natural sciences, the work of Dr. Uskoković draws inspiration from arts and humanities, including philosophy.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References:

- Ahn TK, Lee DH, Kim TS, Jang GC, Choi S, Oh JB, Ye G, Lee S (2018) Modification of Titanium Implant and Titanium Dioxide for Bone Tissue Engineering. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1077:355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikin A, Aikin CR (1807) Dictionary of Chemistry and Mineralogy, with an Account of the Processes Employed in Many of the Most Important Chemical Manufactures, Vol. II London: John and Arthur Arch, Cornhill, pp. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Albee FH (1920) Studies in bone growth: triple calcium phosphate as a stimulus to osteogenesis. Annals in Surgery 71(1):32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basic Energy Sciences Advisory Committee. (2015). Challenges at the Frontiers of Matter and Energy: Transformative Opportunities for Discovery Science. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson G (1972) Steps to An Ecology of Mind. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson G (1979) Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett S (1953) Waiting for Godot: A Tragicomedy in Two Acts. New York, NY: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjakul S, Mad-Ali S, Senphan T, Sookchoo P (2017) Biocalcium powder from precooked skipjack tuna bone: Production and its characteristics. Journal of Food Biochemistry 41, e12412. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle RA, Lenton TM, Williams HTP (2007) Neoproterozoic ‘snowball Earth’ glaciations and the evolution of altruism. Geobiology 5 (4) 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht B (1955). Life of Galileo In Bertolt Brecht: Plays, Poetry and Prose. Willett John and Manheim Ralph (ed.). London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Campana V, Milano G, Pagano E, Barba M, Cicione C, Salonna G, Lattanzi W, Lorgoscino (2014) Bone substitutes in orthopaedic surgery: from basic science to clinical practice. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 25(10): 2445–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalbou S, Combes C, Eichert D, Rey C (2004) Adaptative physico-chemistry of bio-related calcium phosphates. Journal of Materials Chemistry 14, 2148–2153. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland D (2010) Marshall McLuhan: You Know Nothing of My Work!, New York, NY: Atlas & Co., pp. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Crabb C (2006) Doris #23. Portland, OR: Microcosm Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Craven BM (1976) Crystal Structure of Cholesterol Monohydrate. Nature 260, 727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennick R, Spencer J (2011) Teaching and learning in small groups In: Medical Education: Theory and Practice E-Book, Dornan T, Mann KV. Scherpbier AJJA, Spencer JA (eds.), Oxford, UK: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Djerassi C (2012) Chemistry in Theatre: Insufficiency, Phallacy or Both. London: Imperial College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Djerassi C, Hoffmann R (2001) Oxygen. New York, NY: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- Do TN, Lee WH, Loo CY, Zavgorodniy AV, Rohanizadeh R (2012) Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as vectors for gene delivery. Therapeutic Delivery 3, 623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin SV (2009) Calcium Orthophosphates in Nature, Biology and Medicine. Materials 2:399–498. [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin SV (2013) A detailed history of calcium orthophosphates from 1770s till 1950. Materials Science and Engineering C 33, 3085–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürrenmatt F (1964). The Physicists. Translated from German by James Kirkup New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dylan B (1975) Idiot Wind In: Blood on the Tracks, New York, NY: Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Eftekharzadeh S, Sabetkish N, Sabetkish S, Kajbafzadeh AM (2017) Comparing the bulking effect of calcium hydroxyapatite and Deflux injection into the bladder neck for improvement of urinary incontinence in bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. International Urology and Nephrology 49(2):183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliaz N, Metoki N (2017). Calcium phosphate bioceramics: A review of their history, structure, properties, coating technologies and biomedical applications. Materials 10, 334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple M (2018) Review of potential health risks associated with nanoscopic calcium phosphate. Acta Biomaterialia 77, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essamlali Y, Amadine O, Larzek M, Len C, Zahouily M (2017) Sodium Modified Hydroxyapatite: Highly Efficient and Stable Solid-Base Catalyst for Biodiesel Production. Energy Conversion and Management 149, 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Euclidis (1888) Elementa. Heiberg JL (ed.), Leipzig: B. G. Teubner [Google Scholar]

- Farley JC (2012) The Economics of Sustainability In: Sustainability: Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by Cabezas Heriberto and Diwekar Urmila, Oak Park, IL: Bentham Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fosca M, Komlev VS, Fedotov AY, Caminiti R, Rau JV (2012) Structural study of octacalcium phosphate bone cement conversion in vitro. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 4(11):6202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukase Y, Eanes ED, Takagi S, Chow LC, Brown WE (1990) Setting reactions and compressive strengths of calcium phosphate cements. Journal of Dental Research 69(12):1852–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Wu VM, Pernal S, Uskoković V (2016) Self-Setting Calcium Phosphate Cements with Tunable Antibiotic Release Rates for Advanced Bone Graft Applications. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 8 (12) 7691–7708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini R, Freitag R (2001) Comparison of different types of ceramic hydroxyapatite for the chromatographic separation of plasmid DNA and a recombinant anti-Rhesus D antibody. Bioseparation 9, 359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolewski S, Gorna K (2007) Biodegradable polyurethane cancellous bone graft substitutes in the treatment of iliac crest defects. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A 80(1):94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryshkov O, Klyui NI, Temchenko VP, Kyselov VS, Chatterjee A, Belyaev AE, Lauterboeck L, Iarmolenko D, Glasmacher B (2016) Porous biomorphic silicon carbide ceramics coated with hydroxyapatite as prospective materials for bone implants. Materials Science and Engineering C 68:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier L, Flayeux I, Boschetti E (2001) A dual-mode approach to the selective separation of antibodies and their fragments. Journal of Chromatography B 755, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habraken W, Habibovic P, Epple M, Bohner M (2016) Calcium Phosphates in Biomedical Applications: Materials for the Future? Materials Today 19, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ignjatović NL, Sakač M, Kuzminac I, Kojić V, Marković S, Vasiljević-Radović D, Wu VM, Uskoković V, Uskoković DP (2018) Chitosan Oligosaccharide Lactate Coated Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles as a Vehicle for the Delivery of Steroid Drugs and the Targeting of Breast Cancer Cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 6, 6957–6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, Barkarmo S, Hawthan M, Peruzzi N, Kjellin P, Wennerberg A (2018) Biomechanical, histological, and computed X-ray tomographic analyses of hydroxyapatite coated PEEK implants in an extended healing model in rabbit. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A 106(5):1440–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juntavee N, Juntavee A, Plongniras P (2018) Remineralization potential of nano-hydroxyapatite on enamel and cementum surrounding margin of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing ceramic restoration. International Journal of Nanomedicine 13, 2755–2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Wu VM, Ghosh S, Uskoković V (2016) Gene Delivery Using Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles: Optimization of the Transfection Process and the Effects of Citrate and Poly(L-Lysine) as Additives. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 471, 48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz W (2010) Specific ion effects in colloidal and biological systems. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 15, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lang SB, Tofail SA, Kholkin AL, Wojtaś M, Gregor M, Gandhi AA, Wang Y, Bauer S, Krause M, Plecenik A (2013) Ferroelectric polarization in nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite thin films on silicon. Scientific Reports 3:2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassaigne M (1847) Solubility of carbonate of lime in water containing carbonic acid. Philosophical Magazine Ser. 3 30:297–298. [Google Scholar]

- Lenton S, Nylander T, Teixeira SC, Holt C (2015) A review of the biology of calcium phosphate sequestration with special reference to milk. Dairy Science and Technology 95, 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GX, Xue CB, Zhu PZ (2017). Removal of carmine from aqueous solution by carbonated hydroxyapatite nanorods. Nanomaterials 7, 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macewen W (1881) Observations concerning transplantation of bone. Illustrated by a case of inter-human osseous transplantation, whereby over two-thirds of the shaft of a humerus was restored. Proceedings of the Royal Society London 32:232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Maiti GC, Freund F (1981) Influence of Fluorine Substitution on the Proton Conductivity of Hydroxyapatite. Journal of Chemical Society Dalton Transactions 1981 (4) 949–955. [Google Scholar]

- Manda MG, da Silva LP, Cerqueira MT, Pereira DR, Oliveira MB, Mano JF, Marques AP, Oliveira JM, Correlo VM, Reis RL (2018) Gellan gum-hydroxyapatite composite spongy-like hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A 106(2):479–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmel M (1930) On the structure of apatite. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie 75:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Jyothi S, Moogi P, Finger WJ, Sasaki K (2018) Novel treatment of in-office tooth bleaching sensitivity: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry 30, 254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LB, Berkowitz JK, Yesinowski JP (1992) F-19 and P-31 magic-angle spinning nuclear-magnetic-resonance of antimony(III)-doped fluoroapatite phosphors-dopant sites and spin diffusion. Physical Review B 45, 5347–5360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova D, Möhlmann D, Wagner D (2007) Survival of methanogenic archaea from Siberian permafrost under simulated Martian thermal conditions. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 37, 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Hiratai R, Yamashita K (2012) Bone mineral as an electrical energy reservoir. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A 100, 1368–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan R, Agarwal T, Mishra D, Maji S, Mohanty S, Mukhopadhyay A, Maiti TK (2017) Ectopic vascularized bone formation by human mesenchymal stem cell microtissues in a biocomposite scaffold. Colloids and Surfaces B 160:661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Náray-Szabó S (1930) The structure of apatite (CaF)Ca4(PO4)3. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie 75:387–398. [Google Scholar]

- Niederberger M, Colfen H (2006) Oriented attachment and mesocrystals: non-classical crystallization mechanisms based on nanoparticle assembly. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 8, 3271–3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva J, De Pablo J, Cortina J-L, Cama J; Ayora C (2011) Removal of cadmium, copper, nickel, cobalt and mercury from water by Apatite II™: column experiments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 194, 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernal SP, Wu VM, Uskoković V (2017) Hydroxyapatite as a Vehicle for the Selective Effect of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles against Human Glioblastoma Cells. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 9 (45) 39283–39302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Player TC, Hore PJ (2018) Posner qubits: spin dynamics of entangled Ca9(PO4)6 molecules and their role in neural processing. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 15, 20180494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D, Drancourt M, Azza S, Nappez C, Guiey R, Rolain JM, Fourquet P, Campagna B, La Scola B, Mege JL, Mansuelle P, Lechevalier E, Berland Y, Gorvel JP, Renesto P (2008) Nanobacteria Are Mineralo Fetuin Complexes. PLoS Pathogenesis 4 (2): e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnayake JTB, Mucalo M, Dias GJ (2017) Substituted hydroxyapatites for bone regeneration: A review of current trends. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research B 105, 1285–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner BD, Hoffman AS, Schoen FJ, Lemons JK (2012) Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rigali M, Brady PV, Moore R (2016) Radionuclide removal by apatite. American Mineralogist 101, 2611–2619. [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe HE, Schorlemmer C (1881) A treatise on chemistry Volume I: The Non-metallic elements. London: Macmillan and Co., pp. 458. [Google Scholar]

- Roycroft PD, Cuypers M (2015) The etymology of the mineral name ‘apatite’: a clarification. Irish Journal of Earth Sciences 33, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Kurosawa Y, Okuyama T (2013) Scanning electron microscopy-based approach to understand the mechanism underlying the adhesion of dengue viruses on ceramic hydroxyapatite columns. PLoS One 8(1):e53893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz H, Reider W, Irsen S, Leukers B, Tille C (2005) Three-dimensional printing of porous ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research B 74, 782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock SR (2015) The mineral-collagen interface in bone. Calcified Tissue International 97, 262–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppard T (1993) Arcadia: A Play in Two Acts, Los Angeles, CA: Samuel French. [Google Scholar]

- Suda H, Yashima M, Kakihana M, Yoshimura M (1995) Monoclinic ↔ Hexagonal Phase Transition in Hydroxyapatite Studied by X-Ray Powder Diffraction and Differential Scanning Calorimeter Techniques. Journal of Physical Chemistry 99, 6752–6754. [Google Scholar]

- Swift MW, van de Walle CG, Fisher MPA (2018) Posner molecules: from atomic structure to nuclear spins. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 20, 12373–12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofail SAM, Baldisserri C, Haverty D, McMonagle JB, Erhart J (2009) Pyroelectric syrface charge in hydroxyapatite ceramics. Journal of Applied Physics 106, 106104. [Google Scholar]

- Tolkien JRR (1954) The Lord of the Rings. Crown Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Tománek D (2011) Fame on Sale: Pitfalls of the Ranking Game. Materials Express 1 (4) 355–356. [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall KT (2004) False Alarm In: Eye to the Telescope, London: Relentless. [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V (2012) On Love in the Realm of Science. Technoetic Arts 10 (2–3) 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V (2014) Chemical Reactions as Petite Rendezvous: The Use of Metaphor in Materials Science Education. Journal of Materials Education 36 (1–2) 25–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V (2015a) Nanostructured Platforms for the Sustained and Local Delivery of Antibiotics in the Treatment of Osteomyelitis. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems 32 (1) 1–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V (2015b) The Role of Hydroxyl Channel in Defining Selected Physicochemical Peculiarities Exhibited by Hydroxyapatite. RSC Advances 5, 36614–36633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V (2015c) When 1 + 1 > 2: Nanostructured Composite Materials for Hard Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials Science and Engineering C 57, 434–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V (2017) Rethinking Active Learning as the Paradigm of Our Times: Towards Poetization of Education in the Age of STEM. Journal of Materials Education 39 (5–6) 241–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Bertassoni LE (2010) Nanotechnology in Dental Sciences: Moving towards a Finer Way of Doing Dentistry. Materials 3 (3) 1674–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Desai TA (2013a) Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles: A Future Therapeutic Platform for the Treatment of Osteomyelitis? Therapeutic Delivery 4 (6) 643–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Desai TA (2013b) Phase Composition Control of Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles for Tunable Drug Delivery Kinetics and Treatment of Osteomyelitis. I. Preparation and Drug Release. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A 101 (5) 1416–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Desai TA (2014) Simultaneous Bactericidal and Osteogenic Effect of Nanoparticulate Calcium Phosphate Powders Loaded with Clindamycin on Osteoblasts Infected with Staphylococcus Aureus. Materials Science and Engineering C 37, 210–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Rau JV (2017) Nonlinear Oscillatory Dynamics of the Hardening of Calcium Phosphate Cements. RSC Advances 7, 40517–40532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Tang S, Wu VM (2018) On Grounds of the Memory Effect in Amorphous and Crystalline Apatite: Kinetics of Crystallization and Biological Response. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 10 (17) 14491–14508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V, Wu VM (2016) Calcium Phosphate as a Key Material for Socially Responsible Tissue Engineering. Materials 9, 434–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout EMM, Van Kralingen GH, El-Massoudi Y, Weinans H, Patka P (2011) Microstructure and biomechanical characteristics of bone substitutes for trauma and orthopaedic surgery. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 12, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Walter P (1821) Wiedereinheilung der bei der trapanation ausgebohrten knochenscheibe. Journal Chir. Augenheilkd 2:571. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles P (1983) Ideology, Methodology, and Neoclassical Economics In: Why Economics is Not Yet a Science, Eichner Alfred S. (ed.), Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Winograd T, Flores F (1987) Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundations for Design. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wopenka B, Pasteris JD (2005) A mineralogical perspective on the apatite in bone. Materials Science and Engineering C 25, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wu VM, Tang S, Uskoković V (2018) Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles as Intrinsic Inorganic Antimicrobials: The Antibacterial Effect. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 10 (40) 34013–34028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu VM, Uskoković V (2017) Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles in Drosophila melanogaster: The Effects of Phase Composition, Crystallinity and the Pathway of Formation. ACS Biomaterials Science and Engineering 3 (10) 2348–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie R, Hu J, Hoffmann O, Zhang Y, Ng F, Qin T, Guo X (2018) Self-fitting shape memory polymer foam inducing bone regeneration: A rabbit femoral defect study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: General Subjects 1862(4):936–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Wang P, Kopittke PM (2018) Tailoring hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to increase their efficiency as phosphorus fertilisers in soils. Geoderma 323, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Young JD, Martel J, Young L, Wu CY, Young A, Young D (2009) Putative nanobacteria represent physiological remnants and culture by-products of normal calcium homeostasis. PLoS One 4(2):e4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MJ, Liu SN, Xu G, Guo YN, Fu JN, Zhang DC (2014) Cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by nanobacteria in human breast cancer cells. International Journal of Nanomedicine 9:265–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann EA, Ritchie RO (2015) Bone as a structural material. Advanced Healthcare Materials 4, 1287–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckermann H (1977). Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States. New York, NY: The Free Press, pp. 134. [Google Scholar]