Abstract

Background/Aims

Efforts to reduce stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) have focused on increasing physician adherence to oral anticoagulant (OAC) guidelines; however, the high early discontinuation rate of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) is a limitation. Although non-VKA OACs (NOACs) are more convenient to administer than warfarin, their lack of monitoring may predispose patients to nonpersistence. We compared the persistence of NOAC and VKA treatment for AF in real-world practice.

Methods

In a prospective observational registry (COmparison study of Drugs for symptom control and complication prEvention of Atrial Fibrillation [CODE-AF] registry), 7,013 patients with nonvalvular AF (mean age 67.2 ± 10.9 years, women 36.4%) were consecutively enrolled between June 2016 and June 2017 from 10 tertiary hospitals in Korea. This study included 3,381 patients who started OAC 30 days before enrollment (maintenance group) and 572 patients who newly started OAC (new-starter group). The persistence rate of OAC was evaluated.

Results

In the maintenance group, persistence to OAC declined during 6 months, to 88.3% for VKA and 95.5% for NOAC (p < 0.0001). However, the persistence rate was not different among NOACs. In the new-starter group, persistence to OAC declined during 6 months, to 78.9% for VKA and 92.1% for NOAC (p < 0.0001). The persistence rate was lower for rivaroxaban (83.7%) than apixaban (94.6%) and edoxaban (94.1%, p < 0.001). In the new-starter group, diabetes, valve disease, and cancer were related to nonpersistence of OAC.

Conclusions

Nonpersistence was significantly lower with NOAC than VKA in both the maintenance and new-starter groups. In only the new-starter group, apixaban or edoxaban showed higher persistence rates than rivaroxaban.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Anticoagulants, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, Apixaban

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common, sustained cardiac arrhythmia occurring in 1% to 2% of the general population [1], and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [2]. AF is associated with a 5-fold increase in stroke risk, and one in five cases of stroke is attributed to this arrhythmia [3]. Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) have been the mainstay of oral anticoagulant (OAC) treatment for several decades and reduce the relative risk of stroke in patients with AF by 64% [4]. However, non-VKA OACs (NOACs), such as the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran and the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, are now approved for stroke prevention in patients with AF. The NOACs have all been shown to be at least as effective and safe as warfarin in large randomized controlled trials [5-7], with a lower incidence of intracranial hemorrhage, and have now been incorporated into guidelines [8,9].

As patients with AF have an elevated risk of developing ischemic stroke when untreated, assessing OAC persistence is crucial to understanding the extent to which patients continuously receive the benefit of stroke prevention while tolerating the possible adverse effects. Lack of adherence to warfarin has long been recognized in clinical practice, and is believed to be due to the inconvenience of frequent warfarin monitoring, dietary restrictions, and numerous drug interactions [2,10]. NOACs also have several potential advantages compared with VKAs, such as fewer drug-drug and food-drug interactions and no requirement for routine coagulation monitoring [11]. Although the lack of routine monitoring with NOAC use may be seen as an advantage, patients taking NOACs may have less contact with clinicians, providers may be less aware of the patients’ medication-taking behaviors, and, consequently, NOAC nonpersistence may be anticipated in clinical practice [12]. An important question is whether the ease of NOAC use has translated into better treatment persistence. Unfortunately, information from large randomized controlled studies [5,13] cannot provide a reliable indication of the levels of persistence that might be anticipated in real-world practice. Some studies, largely from pharmacy or health system administrative data and all limited to a single NOAC, have attempted to estimate persistence. Moreover, some studies aimed to determine whether NOACs show improved persistence compared with VKA [14-18]. Research using real-world data is key to observing persistence without the influence of a study environment, such as in a clinical trial. However, studies with real-world data of new drugs require time for information to naturally accumulate as the drugs become routinely used in clinical practice. At the time when this study was performed in 2016, edoxaban was the most recently approved OAC for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular AF. With rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran having also been in circulation for some years, it is now timely to use real-world data to assess OAC treatment persistence. To address the important question of OAC persistence in real-world practice after the approval of NOACs, we aimed to compare the persistence of VKAs and NOACs through a prospective, multicenter cohort study of patients with nonvalvular AF.

METHODS

Study design and centers

The COmparison study of Drugs for symptom control and complication prEvention of Atrial Fibrillation (CODE-AF) is a prospective, multicenter, observational study performed in AF patients aged > 18 years with valvular disease of more than moderated degree, who have undergone valve operation and are attending any of 10 tertiary centers encompassing all geographical regions of South Korea.

The aim of the CODE-AF registry is to describe the clinical epidemiology of patients with AF, and to determine the diagnostic and therapeutic processes (including the organization of programs for AF management) applied in these patients and the clinical outcomes. The registry was designed and coordinated by the Korea Heart Rhythm Society, which provides support to related committees, national coordinators, and participating centers. Data are entered in a common electronic database that limits inconsistencies and errors and provides online help for key variables. Each center has access to its own data and data from all other participating centers. The study was approved by the ethics committee of each center (4-2016-0105), and all patients provided informed consent for their inclusion. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02786095).

Patients

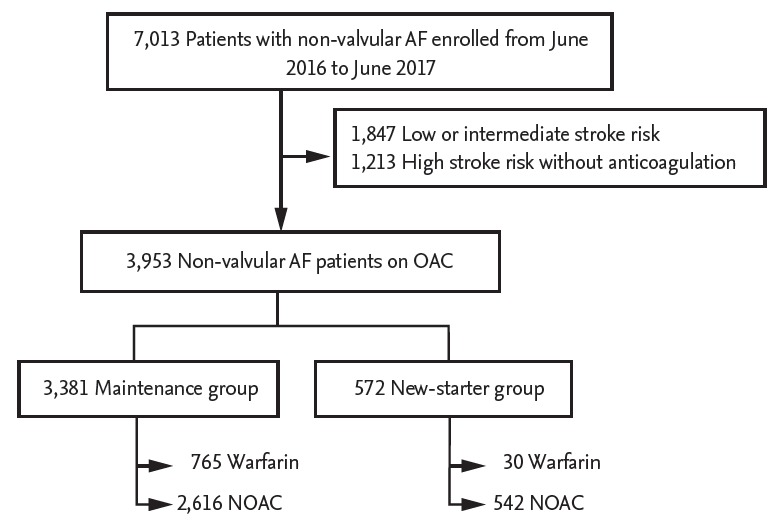

In a prospective observational registry (CODE-AF registry), 7,013 patients with nonvalvular AF (mean age 67.2 ± 10.9 years, women 36.4%) were consecutively enrolled, including those with mild mitral stenosis, between June 2016 and June 2017 from 10 tertiary hospitals in South Korea. Patients with a low or intermediate stroke risk (n = 1,847) and those with a high stroke risk but without anticoagulation treatment (n = 1,213) were excluded. Finally, this study included 3,381 patients who started OAC > 30 days before enrollment (maintenance group) and 572 patients who newly started OAC (new-starter group) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment. AF, atrial fibrillation; OAC, oral anticoagulant; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist (VKA) OAC.

The following patient parameters were assessed: demographics, comorbidities (including congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, transient ischemic attack [TIA], thromboembolism, and vascular disease, such as a prior myocardial infarction or the presence of atherosclerotic vascular disease [e.g., peripheral artery disease and aortic or carotid plaques]), stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score), bleeding risk (Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly [HAS-BLED]) scores, type of OAC prescribed, concomitant cardiovascular drugs, number of outpatient primary care physician visits in a defined period, and, in VKA-treated patients, frequency of international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring.

Study analysis

Patients were categorized into five separate exposure cohorts, according to whether they were initiated or maintained on warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, or edoxaban therapy. Index day was defined as the enrollment date if anticoagulation was maintained more than 30 days before enrollment date, or the initiation day of OAC if anticoagulant was prescribed within 14 days after the first AF diagnosis.

Persistence (or nonpersistence) to therapy was analyzed from the initiation of the index therapy (first prescription date of the initially prescribed therapy) and involved a series of successive prescriptions. (1) Persistence was defined as a refill within the period covered by the previous prescription. This included patients who may have interrupted treatment but received their subsequent prescription within 60 days. (2) Nonpersistence was defined as a permanent discontinuation of therapy or a refill later than 60 days after the end of the period covered by the previous prescription.

For nonpersistent patients, the start of nonpersistence was the last date covered by the last “persistent” prescription. Therefore, the end date of the previous/last prescription was the patient’s time to nonpersistence.

Factors associated with nonpersistence

For NOAC or VKA, factors that may potentially influence persistence were examined. These included age, sex, insurance status, stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score), history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pre-index comorbidities, type of OAC used, and use of cardiovascular and antiplatelet drugs during the 180-day post-index period. Comparisons of persistence with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or VKA therapy at 180 and 360 days were conducted. For the analyses of adherence to dosing regimens with rivaroxaban or dabigatran and the identification of factors that may potentially influence persistence, the treatment period of 180 days was used.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients were described using frequency and percentage distributions for categorical variables, and with descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and median) for continuous and count variables, measured from the patient’s index date or based on the pre-index period (180 days preceding index date), unless otherwise specified. The statistical significance of the extent of differences of patient baseline characteristics and of the differences in outcomes between treatment groups was assessed using the following measures for independent samples: chi-square test for categorical measures and Student’s t test for nonnormally distributed continuous variables, whenever appropriate. The statistical significance of the difference in persistence rates between the treatment groups was tested using the Z test. Factors with a potential influence on treatment persistence were evaluated using a logistic regression model. One model utilizing relevant demographic and clinical variables (Table 1) was run. Variable selection procedures (forward/backward selection) were not applied. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 21.0 statistical software (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). All p values were two-tailed, and values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | All (n = 3,953) | VKA (n = 795) | Dabigatran (n = 827) | Apixaban (n = 1,225) | Rivaroxaban (n = 713) | Edoxaban (n = 393) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 2,198 (55.6) | 490 (61.6) | 496 (60.0) | 622 (50.8) | 388 (54.4) | 202 (51.4) |

| Age, yr | 71.7 ± 8.4 | 72.3 ± 8.2 | 70.1 ± 8.1 | 72.5 ± 8.5 | 71.2 ± 8.4 | 71.8 ± 8.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.6 ± 3.5 | 24.4 ± 3.5 | 25.0 ± 3.3 | 24.6 ± 3.6 | 24.7 ± 3.4 | 24.6 ± 3.4 |

| Type of AF | ||||||

| Paroxysmal | 2,419 (61.2) | 506 (63.6) | 511 (61.8) | 762 (62.2) | 438 (61.4) | 202 (51.4) |

| Persistent | 1,324 (33.5) | 240 (30.2) | 281 (34.0) | 405 (33.1) | 221 (31.0) | 177 (45.0) |

| Permanent | 154 (3.9) | 36 (4.5) | 25 (3.0) | 42 (3.4) | 42 (5.9) | 9 (2.3) |

| OAC duration | ||||||

| New start | 14.5 | 3.8 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 9.1 | 49.1 |

| Maintain | 85.5 | 96.2 | 86.3 | 86.0 | 90.9 | 50.9 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 3.49 ± 1.3 | 3.52 ± 1.4 | 3.32 ± 1.3 | 3.65 ± 1.4 | 3.54 ± 1.3 | 3.21 ± 1.2 |

| HAS-BLED | 2.24 ± 0.9 | 2.88 ± 1.0 | 2.05 ± 0.9 | 2.14 ± 0.8 | 2.03 ± 0.8 | 2.02 ± 0.9 |

| Valve disease | 485 (12.3) | 141 (17.7) | 81 (9.8) | 143 (11.7) | 86 (12.1) | 34 (8.7) |

| Heart failure | 520 (13.2) | 116 (14.6) | 108 (13.1) | 163 (13.3) | 87 (12.2) | 46 (11.7) |

| Hypertension | 3,126 (79.1) | 618 (77.7) | 654 (79.2) | 1,000 (81.6) | 557 (78.1) | 297 (75.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,357 (34.3) | 286 (36.0) | 281 (34.0) | 428 (34.9) | 245 (34.4) | 117 (29.8) |

| History of stroke/TIA | 864 (21.9) | 170 (21.4) | 181 (21.9) | 282 (23.0) | 180 (25.2) | 51 (13.0) |

| History of MI | 155 (3.9) | 39 (4.9) | 36 (4.4) | 45 (3.7) | 27 (3.8) | 8 (2.0) |

| History of PAD | 287 (7.0) | 62 (7.8) | 52 (6.3) | 96 (7.8) | 51 (7.2) | 17 (4.3) |

| Cancer | 436 (11.0) | 68 (8.6) | 73 (8.8) | 169 (13.8) | 64 (9.0) | 62 (15.8) |

| CKD | 474 (12.0) | 169 (21.3) | 33 (4.0) | 177 (14.4) | 68 (9.5) | 27 (6.9) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1,635 (41.4) | 308 (38.7) | 345 (41.8) | 538 (43.9) | 312 (43.8) | 132 (33.7) |

| History of bleeding | 429 (10.9) | 95 (11.9) | 66 (8.0) | 152 (12.4) | 79 (11.1) | 37 (9.4) |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD.

VKA, vitamin K antagonist; BMI, body mass index; AF, atrial fibrillation; OAC, oral anticoagulant; CHA2DS2-VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age 75 years or older, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke/transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, sex category (female); HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/alcohol concomitantly; TIA, transient ischemic attack; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

The characteristics of the patient population in the maintenance group are described in Table 1. Generally, the patient characteristics were similar between groups for each drug. The cohort consisted of 795 patients taking warfarin and 3,158 patients taking an NOAC. Common comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, history of stroke/TIA, and heart failure. The mean CHA2DS2-VAS scores were 3.52 ± 1.4 and 3.48 ± 1.3 in warfarin and NOAC users, respectively. Apixaban-prescribed patients had higher CHA2DS2-VAS score (3.65 ± 1.4) and HAS-BLED score (2.14 ± 0.8) than those prescribed other OACs. The baseline characteristics in the new-starter and maintenance groups are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Nonpersistence rate

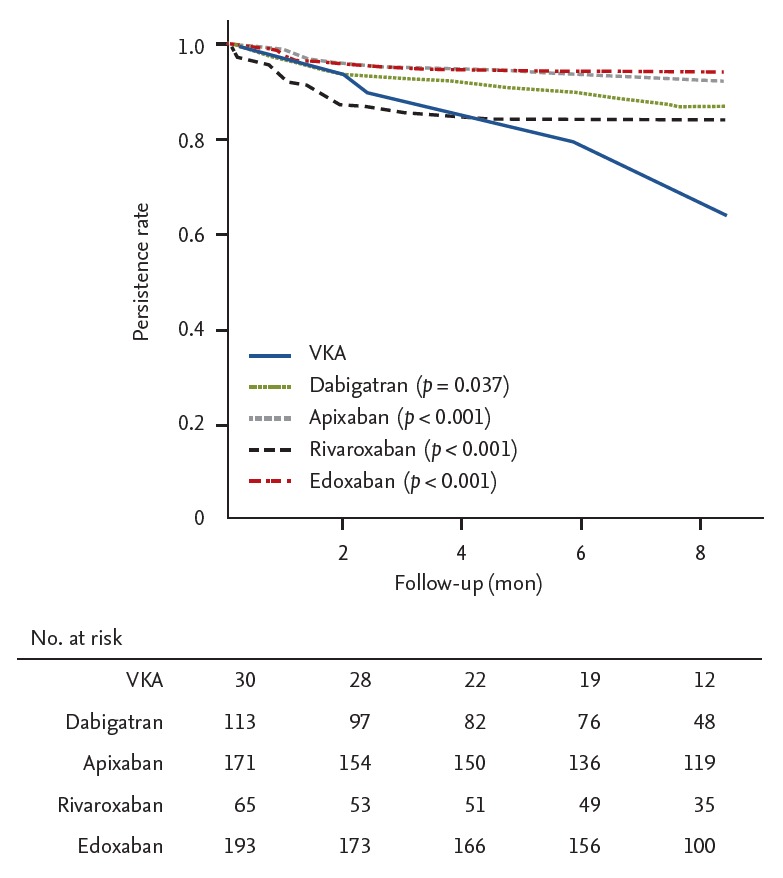

In the new-starter group during a mean follow-up duration of 192 ± 95 days, the nonpersistence rates of each OAC at 3 months were as follows: warfarin 10.4%, rivaroxaban 14.5%, dabigatran 6.4%, apixaban 4.8%, and edoxaban 5.4%. The nonpersistence rates of each OAC at 6 months were as follows: warfarin 21.1%, rivaroxaban 16.3%, dabigatran 10.8%, apixaban 5.4%, and edoxaban 5.9%. The 6-month nonpersistence rates of all of NOAC were significantly lower compared to that of warfarin (p < 0.001). In the new-starter group, apixaban or edoxaban showed a lower nonpersistence rate than rivaroxaban (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve free from persistence in the new-starter group. VAK, vitamin K antagonist.

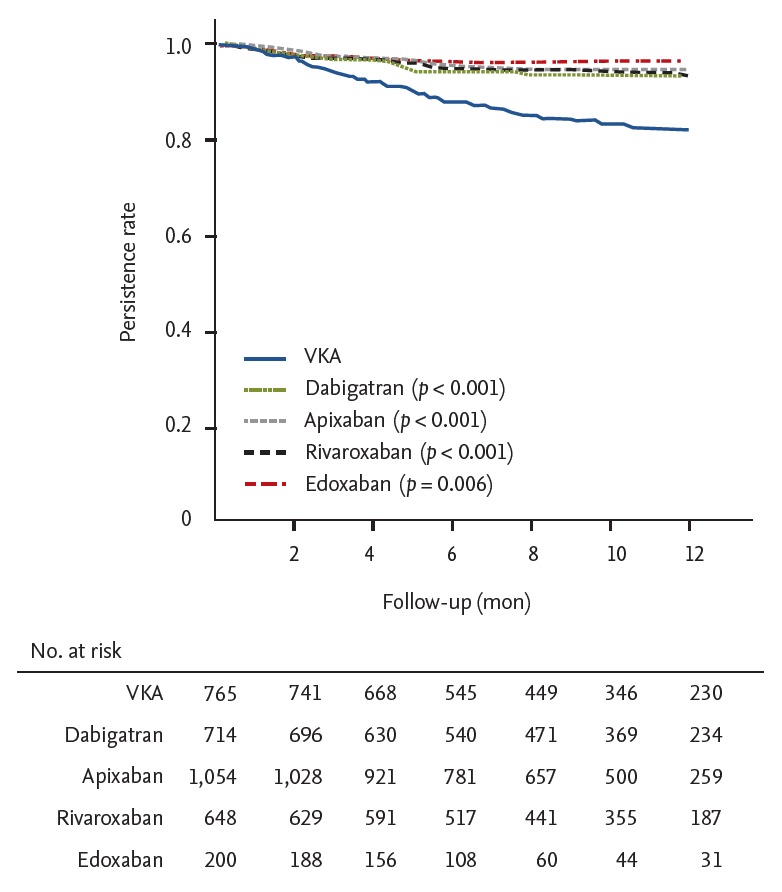

In the maintenance group during a mean follow-up duration of 266 ± 107 days, the nonpersistence rates of each OAC at 3 months were as follows: warfarin 5.5%, rivaroxaban 2.6%, dabigatran 2.9%, apixaban 1.3%, and edoxaban 2.0%. The nonpersistence rates of each OAC at 6 months were as follows: warfarin 11.7%, rivaroxaban 5.2%, dabigatran 5.9%, apixaban 4.3%, and edoxaban 3.0%. Nonpersistence to NOAC was significantly lower than to warfarin (p < 0.001). There was no difference among the four NOACs (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve free from persistence in the maintenance group. VAK, vitamin K antagonist.

In order to confirm the pattern of maintenance group, additional analysis was performed by changing the definition of maintenance group to patients who had been using NOAC for more than 60 and 90 days, respectively. The results confirmed that all three groups of patients (NOAC usage for more than 30, 60, and 90 days) showed a similar pattern in terms of discontinuation (Supplement Figs. 1 and 2).

Especially in patients with valve disease, warfarin was discontinued mainly for the change of NOAC in maintenance group (66.7%). Persistence rate was not different between twice-daily and once-daily medications (log rank test, p = 0.928) (data is not presented).

Factors related to nonpersistence

In new-starter group, diabetes mellitus (odds ratio [OR], 0.53; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29 to 0.97; p = 0.04), valve disease (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.91; p = 0.03), and cancer (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.9; p = 0.03) were related to nonpersistence of OAC (Table 2). However, in maintenance group, significant factors related to nonpersistence were not observed.

Table 2.

Predictors of nonpersistence in the maintenance and new-starter groups

| Variable | New-starter |

Maintenance |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Hypertension | 1.99 (0.85–4.65) | 0.11 | 0.78 (0.57–1.07) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.53 (0.29–0.97) | 0.04 | 1.28 (0.96–1.72) | 0.09 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.59 (0.13–2.73) | 0.50 | 0.93 (0.43–2.02) | 0.86 |

| Valve disease | 0.43 (0.2–0.91) | 0.03 | 1.23 (0.8–1.9) | 0.35 |

| Heart failure | 0.85 (0.37–1.93) | 0.69 | 0.99 (0.67–1.47) | 0.96 |

| PAOD | 0.97 (0.22–4.35) | 0.97 | 1.03 (0.56–1.89) | 0.92 |

| CVA | 1.51 (0.61–3.78) | 0.37 | 1.21 (0.86–1.69) | 0.28 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.09 (0.59–2.03) | 0.78 | 1.32 (0.99–1.75) | 0.06 |

| CKD | 0.9 (0.35–2.35) | 0.83 | 1.18 (0.75–1.83) | 0.47 |

| Cancer | 0.42 (0.2–0.9) | 0.03 | 0.81 (0.55–1.21) | 0.31 |

| Bleeding | 1.09 (0.42–2.81) | 0.86 | 0.98 (0.63–1.52) | 0.93 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PAOD, peripheral artery occlusive disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Change of OAC

In new-starter group, OAC was discontinued in 36.4%, 60.0%, 80.0%, and 63.6% of patients taking dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban, respectively. Fig. 4A shows the first change of OAC or other NOAC in these patients. The types of OAC were not changed more than two times in any of the new-starter patients.

Figure 4.

Change of oral anticoagulant method in the new-starter (A) and maintenance (B) groups. VAK, vitamin K antagonist.

In maintenance group, for patients who were nonpersistent to dabigatran, 90.5% switched to other NOACs, 4.8% to warfarin, and 4.8% completely stopped OAC. In those who were nonpersistent to apixaban, 68.9% switched to other NOACs and 31.1% completely stopped OAC. In those who were nonpersistent to rivaroxaban, 67.7% switched to other NOACs and 32.4% completely stopped OAC. All patients who were nonpersistent to edoxaban switched to other NOACs (Fig. 4B). The types of OAC were changed two and three times in five patients (2.5%) and one patient (0.4%), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

Our study found that the persistence rate was significantly higher with NOACs than with VKAs in both the maintenance and new-starter groups. Second, there was no difference in the persistence rate among different NOACs in the maintenance group. However, apixaban or edoxaban showed a higher persistence rate than rivaroxaban in the new-starter group. Finally, diabetes mellitus, valve disease, and cancer were related to the nonpersistence of OAC in the new-starter group.

Nonpersistence rate

Several factors may lead to differences in persistence and adherence among treatments in routine practice. VKA therapy involves regular INR monitoring and dose adjustments [19]. In addition, VKA therapy is influenced by numerous interactions between drugs and foods (e.g., foods rich in vitamin K) [11]. As NOACs do not require routine monitoring, do not show food-drug interactions, and show fewer drug-drug interactions, our findings of a higher persistence with NOAC than with VKA may be explained by the improved convenience of these modern therapies.

Currently, the information available on NOAC nonpersistence in clinical practice, from studies examining individual agents, shows that 23% to 49% of patients are nonpersistent to dabigatran, 19% to 42% of patients are nonpersistent to rivaroxaban, and 14% to 17% of patients are nonpersistent to apixaban [11,16,20-24]. There are no available real-world nonpersistence data for edoxaban. Recent studies show that the early (6 months) nonpersistence to dabigatran and rivaroxaban are as high as the 1-year nonpersistence rates of 25% to 32% [25-27]. However, the NOAC persistence rate was much higher in this study. This result might be related to the full insurance coverage of NOAC in Korea.

Previous studies demonstrated that nonpersistence was higher with dabigatran and rivaroxaban than with apixaban [23,24,28,29]. However, the persistence rate of edoxaban has not been well evaluated. This study showed that nonpersistence to apixaban or edoxaban was lower than that to rivaroxaban, with the nonpersistence rate being similar between edoxaban and apixaban, in the new-starter group. Interestingly, the apixaban persistence was higher than that of other OACs (albeit after the first 100 days since initiation), as it has been previously speculated that the once-a-day regimen is more convenient than twice-a-day regimens, thus probably leading to better persistence [30]. Our study showed that persistence is also likely affected by other factors. One possible explanation for the observed improved persistence to apixaban, which is given in a once-a-day regimen, is that patients taking this drug may have greater AF severity and/or more comorbidities (as observed in our study), which could increase their understanding of the importance of treatment continuation.

In the maintenance group in this study, there was no difference in the persistence rate among NOACs.

Factors related to persistence of OAC

In this study, diabetes mellitus, valve disease, and cancer were related to the persistence of OAC in the new-starter group. This may be related to the increased understanding of these patients about the importance of persistence and adherence to prescribed regimens. Therefore, better education of patients may encourage persistence. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study showing a high persistence rate in patients with diabetes [21]. In contrast, no factors were significantly related to nonpersistence in the maintenance group. However, it is important to point out that these findings should not be overinterpreted, as they were derived from a single regression model that is only used for retrospectively collected database entries.

Our study demonstrated that twice-daily dosing and frequent gastrointestinal adverse effects may contribute to dabigatran nonpersistence. It is recognized that as the frequency of drug administration increases, nonpersistence to medication use decreases [31]. However, despite the additional inconveniences of dabigatran use compared with rivaroxaban that might be considered to predispose patients to dabigatran nonpersistence, we found a rather small magnitude of difference in the nonpersistence rate between dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Our study shows that discontinuation rate at the beginning of OAC medication is generally high, followed by a low rate of discontinuation thereafter. These were the same patterns as those shown in previous study [32,33].

Second, the price of NOAC in Korea is relatively inexpensive compared to those of other countries. Most of the patients enrolled in this study were receiving medical care at tertiary centers, and can thus be considered relatively affluent. Therefore, there may have been some selection bias.

Patterns of OAC changes

After showing nonpersistence to NOAC except dabigatran, a lower proportion of patients restarted NOAC. In addition, there were nearly twice as many patients nonadherent to rivaroxaban who completely stopped all anticoagulation therapy compared with patients nonadherent to dabigatran. This lack of anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention after nonpersistence to apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban may have been related to the reluctance to use anticoagulation among less healthy patients, and may have translated into the especially high risk of adverse cerebrovascular events, stroke, and TIA. Although it is unknown why patients were less likely to restart OAC after becoming nonpersistent to medication, it is possible for clinicians to monitor for nonpersistence and consider the possible stroke prevention therapies in suitable patients to help reduce the risk of adverse clinical outcomes.

Study limitation

The number of patients started on NOAC was relatively smaller than the number of those started on VKA. Moreover, because of the relatively brief follow-up period, our estimates of the persistence rates of NOAC may be imprecise, although they seem to be much greater than those of VKA, and were consistent with those reported by other single-drug studies. Our results should spur further studies investigating this question. While patients prescribed with NOAC and VKA showed small baseline differences that might have influenced our results, a sensitivity analysis matching cohorts on individual CHA2DS2-VASc components showed almost no difference from the unmatched analysis. However, there may be residual confounding that we cannot exclude in a cohort study. A small proportion of patients switched from VKA to NOAC, and vice versa, which we addressed by conducting a competing risk analysis, as such patients would be categorized as remaining on OAC treatment. Patients who switched from VKA to NOAC had a similar persistence as those who were started on NOAC at 1 year. Our data are very limited for the follow-up of NOAC use after 1 year.

In future studies, it will be important to ascertain whether the significant persistence advantage of NOAC over VKA continues in the long term. The reason for discontinuation of OAC is difficult to determine in cohort studies; prospective studies would be required to determine whether discontinuation was appropriate, whether the discontinuation was in response to bleeding, and the outcome of discontinuation after stopping for bleeding, as well as to inform strategies to reduce anticoagulant discontinuation. It is likely that patient preferences, values, and attitudes toward stroke prevention and bleeding risk will have a significant role in determining persistence, as they do in the decision to start anticoagulant therapy [34,35]; however, this study does not allow examining such issues. A similar issue arises in ascertaining the reasons for switching between NOAC and VKA in this study.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The persistence rate was signif icantly higher with non-vitamin K antagonist (VKA) oral anticoagulants (NOACs) than with VKAs in a contemporary prospective, multicenter Korean atrial fibrillation registry.

2. There was no difference in the persistence rate among different NOACs in the maintenance group. However, apixaban or edoxaban showed a higher persistence rate than rivaroxaban in the new-starter group.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2017R1A2B3003303), and grants from the Korean Healthcare Technology R&D project funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (HI16C0058 and HI15C1200).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplementary Materials

Baseline characteristics of patients in maintenance group analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients in new-start group analysis

Kaplan-Meier curve free from persistence in the maintenance group (60 days before enrollment). VAK, vitamin K antagonist.

Kaplan-Meier curve free from persistence in the maintenance group (90 days before enrollment). VAK, vitamin K antagonist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee H, Kim TH, Baek YS, et al. The trends of atrial fibrillation-related hospital visit and cost, treatment pattern and mortality in Korea: 10-year nationwide sample cohort data. Korean Circ J. 2017;47:56–64. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:e199–e267. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim TH, Yang PS, Uhm JS, et al. CHA(2)DS(2)-VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 [doubled], diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack [doubled], vascular disease, age 65-74, female) for stroke in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: a Korean nationwide sample cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48:1524–1530. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857–867. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 Focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719–2747. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e1–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You JJ, Singer DE, Howard PA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e531S–e575S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson WW, Song X, Coleman CI, et al. Medication persistence and discontinuation of rivaroxaban versus warfarin among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:2461–2469. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.933577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shore S, Ho PM, Lambert-Kerzner A, et al. Site-level variation in and practices associated with dabigatran adherence. JAMA. 2015;313:1443–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai K, Erickson SC, Yang J, Harada AS, Solow BK, Lew HC. Adherence, persistence, and switching patterns of dabigatran etexilate. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:e325–e332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel J, Mundell D, Boga T, Sasse A. Dabigatran for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: early clinical experience in a hospital population and comparison to trial data. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zalesak M, Siu K, Francis K, et al. Higher persistence in newly diagnosed nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients treated with dabigatran versus warfarin. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:567–574. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shore S, Carey EP, Turakhia MP, et al. Adherence to dabigatran therapy and longitudinal patient outcomes: insights from the veterans health administration. Am Heart J. 2014;167:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laliberte F, Cloutier M, Nelson WW, et al. Real-world comparative effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban and warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1317–1325. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.907140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witt DM. Approaches to optimal dosing of vitamin K antagonists. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:667–672. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1324713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel MR, Hellkamp AS, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Outcomes of discontinuing rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: analysis from the ROCKET AF trial (Rivaroxaban Once-Daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beyer-Westendorf J, Forster K, Ebertz F, et al. Drug persistence with rivaroxaban therapy in atrial fibrillation patients-results from the Dresden non-interventional oral anticoagulation registry. Europace. 2015;17:530–538. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorst-Rasmussen A, Skjoth F, Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Lip GY, Lane DA. Dabigatran adherence in atrial fibrillation patients during the first year after diagnosis: a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:495–504. doi: 10.1111/jth.12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forslund T, Wettermark B, Hjemdahl P. Comparison of treatment persistence with different oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1983-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao X, Abraham NS, Alexander GC, et al. Effect of adherence to oral anticoagulants on risk of stroke and major bleeding among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003074. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. Warfarin discontinuation after starting warfarin for atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:624–631. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.937680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Holbrook AM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Persistence with therapy among patients treated with warfarin for atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1687–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackevicius CA, Tsadok MA, Essebag V, et al. Early non-persistence with dabigatran and rivaroxaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2017;103:1331–1338. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson ME, Lefevre C, Collings SL, et al. Early real-world evidence of persistence on oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a cohort study in UK primary care. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011471. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collings SL, Lefevre C, Johnson ME, et al. Oral anticoagulant persistence in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a cohort study using primary care data in Germany. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubboli A. Adherence to and persistence with non-vitamin K-antagonist oral anticoagulants: does the number of pills per day matter? Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:1845–1847. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1086993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyer-Westendorf J, Ehlken B, Evers T. Real-world persistence and adherence to oral anticoagulation for stroke risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2016;18:1150–1157. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiga T, Naganuma M, Nagao T, et al. Persistence of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant use in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: a single-center observational study. J Arrhythm. 2015;31:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lane DA, Lip GY. Patient’s values and preferences for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: balancing stroke and bleeding risk with oral anticoagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:381–383. doi: 10.1160/TH14-01-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahaye S, Regpala S, Lacombe S, et al. Evaluation of patients’ attitudes towards stroke prevention and bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:465–473. doi: 10.1160/TH13-05-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Baseline characteristics of patients in maintenance group analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients in new-start group analysis

Kaplan-Meier curve free from persistence in the maintenance group (60 days before enrollment). VAK, vitamin K antagonist.

Kaplan-Meier curve free from persistence in the maintenance group (90 days before enrollment). VAK, vitamin K antagonist.