Abstract

Pancreas transplantation significantly improves the quality of life for people with type 1 diabetes, primarily by eliminating the need for insulin and frequent blood glucose measurements. Despite the growing numbers of solid organ transplantations worldwide, number of pancreas transplantations in the developing countries` remain significantly low. This difference of pancreas transplantation practices was striking among the participating countries at the 1st International Transplant Network Meeting which was held in Turkey on 2018. In this meeting more than 40 countries were represented. Most of these counties were developing countries located in Africa, Middle East or Asia. The aim of this article is to identify the challenges and limiting factors for pancreas transplantations in these developing countries, by exploring the Turkish example. The challenges faced by the developing countries are broadly classified in four categories; wait-listing, donor pool, team work and follow up. Under these categorical titles, issues are further discussed in detail, giving examples from Turkish practice of pancreas transplantation. Additionally, several solutions to these challenges have been proposed- some of which have already been undertaken by the Turkish Ministry of Health. With the insight and methods presented in this article, pancreas transplantation should be made possible for the potential recipients in the developing countries.

Keywords: Pancreas transplantation, Challenges, Transplantation, Quality of life, Developing country

Core tip: With the insight and methods presented in this article, pancreas transplantation should be made possible for the potential recipients in the developing countries. This short communication attempts to summarize the expert discussions on pancreas transplantation occurring during the 1st International Transplant Meeting involving more than 40 countries’ representatives.

INTRODUCTION

The outcome of pancreas transplantations has improved over the last few decades, with one-year graft survival rates currently at about eighty percent and three-year graft survival rates at sixty percent[1-3]. This has been made possible by improvements in immunosuppression, refinement of surgical technique, better recipient- and donor-selection criteria, and interdisciplinary post-transplant patient management[4,5]. Unlike other forms of transplantation, the main goal of pancreas transplant surgery is to achieve insulin independence, with resultant decreased morbidity and increased quality of life, rather than to save lives[6,7]. Pancreas transplantation can restore glucose control and is intended to prevent, pause, or reverse secondary complications from diabetes, rendering it the definitive treatment option for these patients[8,9].

Pancreas transplantation can be performed by three different routes. The first is pancreas transplantation alone, which accounts for approximately 8% of all pancreas transplantations worldwide[10]. The second and most commonly used route is simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation (SPKT), which provides the best outcome of the three and accounts for 80% of all pancreatic transplants worldwide[11]. The third route is pancreas after kidney transplantation which is an additional option for selected patients[12]. Islet cell transplantation is another important method for achieving insulin independence, but it is beyond the scope of this article.

Despite these positive developments in pancreas transplantation, in Turkey, as well as other developing countries, pancreas transplants have not flourished as much as kidney and liver transplants. In this article, we discuss ways to improve both the number and outcome of pancreas transplantations in developing countries, by exploring the example of Turkey.

COMMUNICATION IS THE KEY

There are many challenges regarding pancreas transplantation in developing countries and communication between specialists is the key to overcome these challenges. To explore these, we retrieved and analyzed the expert discussions by the pancreas transplant panel of the 1st International Transplant Meeting in 2019, where representatives of more than 40 countries presented their experience of different types of transplantations, with a focus on the specific challenges involved. A list of the participating counties can be found in the appendix[13].

ASSESSMENTS AND OPTIMIZATION STRATEGIES

The challenges found to be common in all developing countries were categorized into four main groups. Challenges and strategies for optimizing current practice are discussed in detail below using examples from Turkey’s applications.

Wait-listing

Those on pancreas transplant wait-lists can be classified into two groups. The first consists of typical recipients, who are Type-1 diabetic patients with a low or normal body mass index (BMI). These patients are also prone to ketosis and unable to produce insulin because of autoimmune beta-cell destruction. Their C-peptide levels are extremely low or undetectable[14].

The second group can be classified as atypical recipients, who have Type-2 diabetes[15]. These recipients should be carefully selected, taking into account their BMI and insulin requirement, in order to avoid significant insulin resistance. Before listing for transplantation, their BMI should be less than 30 kg/m2 and their insulin requirement less than 100 units per day. In this way, it can be ensured that the recipient can become euglycemic after pancreas transplantation.

In developing countries, lack of regular exercise, poor nutritional choices, and relatively higher smoking rates lead to higher body mass indices, which may increase the cardiovascular risk in potential recipients[16]. These types of patients are either not listed or are suspended from the list due to their high cardiovascular risk. Consequently, this keeps the SPKT transplant wait-list short and decreases the driving force and motivation of dedicated transplant teams and relevant organizations. Even though it is very difficult to achieve in some areas, more promotion and attention to good healthcare advice in diabetic patients is necessary. According to data from the Turkish Ministry of Health, in 2016, 11 patients were waiting for SPKT, out of a population of 79.8 million. The pancreas-only wait-list consisted of 274 patients, which although is considerably more than the SPKT list is also lower than the expected listing rate when compared to other countries[17].

In some countries, such as Turkey, the allocation system itself can be a reason for the lack of drive to perform such transplants. Under the Turkish system, all organ offers are coordinated by the National Coordination Center (NCC), a branch of the Ministry of Health. The NCC oversees nine regional coordination centers in Turkey[17]. The allocation of organs is performed in a hierarchical fashion, and the NCC is responsible for all assignment and strategic decisions.

With regard to pancreas allocation, the system in Turkey differs from others in Europe and in North America. For example, in the United Kingdom, when deceased-donor kidneys become available for transplantation, they are offered by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant organization through the National Kidney Allocation Scheme, which prioritizes patients listed for a pancreas transplant[18]. As a result of this practice, on each occasion where a pancreas from a deceased donor is available, a single kidney is offered with the pancreas for SPKT. This priority does not exist in the Turkish allocation system. Thus, it is possibly taking the survival benefit opportunity of adding a pancreas to the transplanted donor kidney away from the potential recipient.

Donor pool

For the pancreatic donor pool, there are three options of donation worldwide: Donation after brain death (DBD), donation after circulatory death (DCD), and segmental pancreas living donation[19,20]. There has been an increase in the number of European and American transplant programs that utilize the option of DCD donors for their recipients. All these donors are selected using strict criteria, including a BMI lower than 30, hemoglobin A1c levels within normal ranges, age below 55, and no fatty infiltration of the pancreas. With regard to living-donor segmental pancreas transplantation, the main experience comes from surgeons in Minnesota, where more than 160 such transplants have been performed since 1977, with very good results.

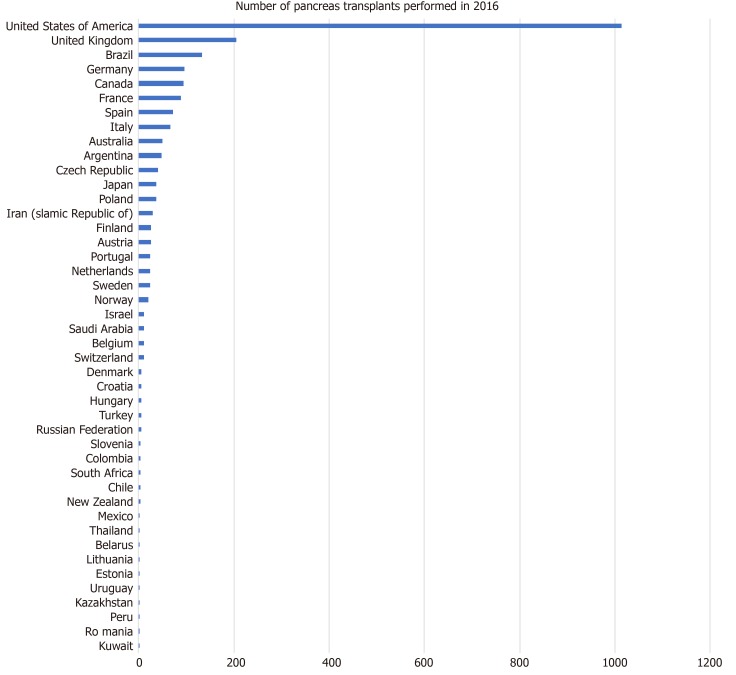

At present, only the DBD resource is utilized in developing countries, including Turkey. The criteria for DBD donation are slightly less strict than DCD and allow donation up to the age of 60 and mild steatosis. The overall rate of DBD donors in developing countries is relatively low, and donors complying with these criteria are even lower. As a result, in 2016, only six deceased-donor pancreas transplants were performed in Turkey from brain-dead donors complying with these criteria. Table 1 and Figure 1 show clearly the huge variability in pancreas transplantations between different countries in 2016.

Table 1.

The number of pancreas transplants performed globally in 2016[27]

| Country | Number of Pancreas Transplants performed in 2016 |

| Kuwait | 1 |

| Romania | 1 |

| Peru | 1 |

| Kazakhstan | 1 |

| Uruguay | 2 |

| Estonia | 2 |

| Lithuania | 2 |

| Belarus | 2 |

| Thailand | 2 |

| Mexico | 3 |

| New Zealand | 4 |

| Chile | 4 |

| South Africa | 4 |

| Colombia | 5 |

| Slovenia | 5 |

| Russian Federation | 6 |

| Turkey | 6 |

| Hungary | 6 |

| Croatia | 7 |

| Denmark | 7 |

| Switzerland | 11 |

| Belgium | 11 |

| Saudi Arabia | 11 |

| Israel | 12 |

| Norway | 20 |

| Sweden | 24 |

| Netherlands | 25 |

| Portugal | 25 |

| Austria | 26 |

| Finland | 27 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 30 |

| Poland | 38 |

| Japan | 38 |

| Czech Republic | 41 |

| Argentina | 48 |

| Australia | 51 |

| Italy | 67 |

| Spain | 73 |

| France | 90 |

| Canada | 95 |

| Germany | 97 |

| Brazil | 134 |

| United Kingdom | 206 |

| United States | 1013 |

Data of the WHO-ONT Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation office (Source: Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation Data).

Figure 1.

The number of pancreas transplants performed globally in 2016[27]. Data of the WHO-ONT Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation office (Source: Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation Data).

In pancreas transplantation, prolonged cold ischemia time is one of the most important risk factors for early pancreatic graft failure[20]. Prolonged cold ischemia can be a difficult issue to manage in a large geographical area such as Turkey, where the peninsula is intercontinental, situated at the crossroads of the Balkans, Caucasus, Middle East, and Eastern Mediterranean. Keeping this geography in mind, existing modes of organ transportation should be used effectively to provide quick solutions for transplant centers.

Lastly, the lack of trained local procurement teams also contributes to the decreased donor pool, either through not being able to retrieve the pancreas in the first place or by injuring the pancreatic vessels or parenchyma and rendering the organ un-transplantable. According to Turkish Ministry of Health data, between 2002 and 2016, 121 DBD organs were unable to be used due to pathological or technical reasons[21].

Team-work

Another challenging aspect of pancreas transplantation is that it requires extensive team work, with an endocrinologist or diabetologist, nephrologist, transplant surgeon particularly trained in pancreas transplantation, intensivist, donor coordinator who can identify potential pancreas donors, and competent retrieval team[22]. Knowledge, clear communication, and trust are essential, and without them, as well as an overall low center volume, pancreas transplantation can result in significantly unfavorable outcomes. To establish clear communication within a team, hierarchical borders may need to be removed as some will come with a lower level of knowledge or contribution of opinion. In some cases, they may turn any discussion field into a monarchial arena.

In addition, the steep learning curve of pancreas transplantation is particularly difficult to accomplish in Turkey because the healthcare and transplantation services are provided by different sectors, such as the Ministry of Health, universities, and the private sector, leading to a lack of collaborative culture.

Follow-up

With potentially life-threatening complications seen in up to 25%-30% of recipients, post-transplant follow-up is critical. This is particularly important during the first 90 d[23], as technical failure is the most common cause of graft loss, accounting for more than seventy percent of all losses[24]. Technical failures can be the result of graft thrombosis, anastomotic leak, and pancreatitis, and management of these serious complications requires skill, expertise, experience, and a patient-centered approach. Therefore, the team of physicians dedicated to the care of the pancreas transplant recipient and the necessary protocols in managing all aspects of the patient care should be prepared in advance, following local consensus and international guidelines, to avoid conflicting views and leave no room for error. Regular audits of patient and graft outcomes are paramount.

DISCUSSION

In order to increase transplantation rates from DBD donors, more effort should be directed towards increasing the assessment and therefore the diagnosis of brain death. Since most of these donors come from Intensive Care Units, the intensive care specialists should be particularly trained in detecting brain death, including complicated cases[25]. Annual nationwide courses are funded by the Ministry of Health in Turkey to train these intensive care specialists and donor coordinators, with the aim of providing a standardized communication platform for handling future difficult cases[2]. However, attendance on these courses is optional.

Training of medical professionals should go hand in hand with educating the public about brain death and organ donation[26]. There is an urgent need to increase public knowledge of the facts and benefits of organ donation and transplantation. Such efforts need to target all socioeconomic levels of the population and start at school age, so that organ donation becomes a normal part of life, much like donating blood.

Also, medical teams should be well prepared to procure donor organs in a timely manner. Therefore, local organ-procurement teams are crucial in large geographical areas to ensure quick, efficient retrieval and optimal preservation of the pancreas. The Turkish Ministry of Health is developing a new program to train local procurement teams, which will be directly in contact with the nine regional coordination centers.

At the transplant centers, it is important to ensure the presence of skilled, experienced, and functioning teams. Because the healthcare and transplantation services in Turkey are provided by different sources, an independent or semi-dependent body should be established to monitor and measure the effectiveness of all three main suppliers; Ministry of Health hospitals, university hospitals, and the private sector. Since the populations served, as well as the service policies of these suppliers, differ from each other in important ways, such an overseeing body would pave the way for standardization of transplantation and donation activities throughout the country. In this way, good clinical practice can be shared for the benefit of patients.

In Turkey, the role of the private sector in healthcare is continuing to increase, and the topics of “equity” and “allocdtion of resources” are being increasingly debated. It is therefore necessary to review the different health policies to ensure an individual-centered approach is put into practice, which in turn should decrease the negative effects of unequal distribution of funds in transplantation, ensuring that everyone’s needs are met in terms of equity and achieving similar donation rates from all sources of healthcare providers.

Last, but not least, the allocation system should be connected to local procurement teams to shorten cold ischemia times and changed to provide the SPKT option for more recipients by allocating the pancreas together with the kidney. Additionally, national data on donation and transplantation should be published annually by the Ministry of Health or an independent establishment, to provide further standardization and dissemination of information nationwide.

CONCLUSION

Successful pancreas transplantation has shown to be efficacious in significantly improving the quality of life of people with diabetes, primarily by eliminating the need for exogenous insulin and frequent daily blood glucose measurements. Therefore, pancreas transplantation should be made possible for potential recipients in developing countries through patient optimization, improving the allocation systems to favor pancreas donation and transplantation where necessary, the adoption of dedicated teams at all stages of the process, including training local procurement teams, and promoting education, audit, and the sharing of good clinical practice.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the Authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 19, 2019

First decision: June 7, 2019

Article in press: November 26, 2019

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kita K, Papalois V S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

Contributor Information

Sanem Guler Cimen, Department of General Surgery, Diskapi Research and Training Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 65000, Turkey.

Sertac Cimen, Department of Urology and Transplantation, Diskapi Research and Training Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 65000, Turkey. s.cimen@dal.ca.

Nicos Kessaris, Department of Nephrology and Transplantation, Guy's Hospital, London SE1 9RT, United Kingdom.

Eyup Kahveci, Turkish Transplant Foundation, Ankara 65000, Turkey.

Acar Tuzuner, Department of General Surgery, Ankara University Medical School, Ankara 65000, Turkey.

References

- 1.Dholakia S, Mittal S, Quiroga I, Gilbert J, Sharples EJ, Ploeg RJ, Friend PJ. Pancreas Transplantation: Past, Present, Future. Am J Med. 2016;129:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stratta RJ, Gruessner AC, Odorico JS, Fridell JA, Gruessner RW. Pancreas Transplantation: An Alarming Crisis in Confidence. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2556–2562. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruessner AC, Gruessner RW. Pancreas transplant outcomes for United States and non-United States cases as reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing and the International Pancreas Transplant Registry as of December 2011. Clin Transpl. 2012:23–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redfield RR, Rickels MR, Naji A, Odorico JS. Pancreas Transplantation in the Modern Era. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2016;45:145–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han DJ, Sutherland DE. Pancreas transplantation. Gut Liver. 2010;4:450–465. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.4.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petruzzo P, Badet L, Lefrançois N, Berthillot C, Dorel SB, Martin X, Laville M. Metabolic consequences of pancreatic systemic or portal venous drainage in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant recipients. Diabet Med. 2006;23:654–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekser B, Mangus RS, Powelson JA, Goble ML, Mujtaba MA, Taber TE, Fridell JA. Impact of duration of diabetes on outcome following pancreas transplantation. Int J Surg. 2015;18:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin X, Petruzzo P, Dawahra M, Feitosa Tajra LC, Da Silva M, Pibiri L, Chapuis F, Dubernard JM, Lefrançois N. Effects of portal versus systemic venous drainage in kidney-pancreas recipients. Transpl Int. 2000;13:64–68. doi: 10.1007/s001470050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meirelles Júnior RF, Salvalaggio P, Pacheco-Silva A. Pancreas transplantation: review. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13:305–309. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082015RW3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masri MA, Haberal MA, Shaheen FA, Stephan A, Ghods AJ, Al-Rohani M, Mousawi MA, Mohsin N, Abdallah TB, Bakr A, Rizvi AH. Middle East Society for Organ Transplantation (MESOT) Transplant Registry. Exp Clin Transplant. 2004;2:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatanarasimhamoorthy VS, Barlow AD. Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation Versus Living Donor Kidney Transplantation Alone: an Outcome-Driven Choice? Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18:67. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1039-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seal J, Selzner M, Laurence J, Marquez M, Bazerbachi F, McGilvray I, Schiff J, Norgate A, Cattral MS. Outcomes of pancreas retransplantation after simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation are comparable to pancreas after kidney transplantation alone. Transplantation. 2015;99:623–628. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.1st International Transplant Network Congress. Available from: https://www.itn2018.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kirchner VA, Finger EB, Bellin MD, Dunn TB, Gruessner RW, Hering BJ, Humar A, Kukla AK, Matas AJ, Pruett TL, Sutherland DE, Kandaswamy R. Long-term Outcomes for Living Pancreas Donors in the Modern Era. Transplantation. 2016;100:1322–1328. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruessner AC, Gruessner RWG. Pancreas Transplantation for Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the United States: A Registry Report. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47:417–441. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erek E, Süleymanlar G, Serdengeçti K. Nephrology, dialysis and transplantation in Turkey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:2087–2093. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.12.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turkish Ministry of Health Data. Ulusal Organ Ve Doku Nakli Koordinasyon Sistemi Yönergesi. Available from: https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,11250/ulusal-organ-ve-doku-nakli-koordinasyon-sistemi-yonergesi.html.

- 18.Hudson A, Bradbury L, Johnson R, Fuggle SV, Shaw JA, Casey JJ, Friend PJ, Watson CJ. The UK Pancreas Allocation Scheme for Whole Organ and Islet Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2443–2455. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi JY, Jung JH, Kwon H, Shin S, Kim YH, Han DJ. Pancreas Transplantation From Living Donors: A Single Center Experience of 20 Cases. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2413–2420. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudolph EN, Dunn TB, Sutherland DER, Kandaswamy R, Finger EB. Optimizing outcomes in pancreas transplantation: Impact of organ preservation time. Clin Transplant. 2017:31. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turkey 2002-2013 Organ Donation And Transplantation Statistics. Available from: http://tonv.org.tr/admin/pages/files/TURKEY-2002-2013-ORGAN-DONATION-AND-TRANSPLANTATION-STATISTICS.pdf.

- 22.Haberal M, Gülay H, Karpuzoğlu T, Büyükpamukçu N, Panayir M, Koç M, Hamaloğlu E, Içel E, Bakkaloğlu M, Alpaslan F. Multiorgan harvesting from heart-beating donors in Turkey. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2566–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhamad T, Malone AF, Brennan DC, Stratta RJ, Chang SH, Wellen JR, Horwedel TA, Lentine KL. Transplant Center Volume and the Risk of Pancreas Allograft Failure. Transplantation. 2017;101:2757–2764. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hampson FA, Freeman SJ, Ertner J, Drage M, Butler A, Watson CJ, Shaw AS. Pancreatic transplantation: surgical technique, normal radiological appearances and complications. Insights Imaging. 2010;1:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s13244-010-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Loo ES, Krikke C, Hofker HS, Berger SP, Leuvenink HG, Pol RA. Outcome of pancreas transplantation from donation after circulatory death compared to donation after brain death. Pancreatology. 2017;17:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haberal M. Transplantation in Turkey. Clin Transpl. 2013:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. Available from: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/summary/