Abstract

Microporous annealed particle (MAP) hydrogels are promising materials for delivering therapeutic cells. It has previously been shown that spreading and mechanosensing activation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) incorporated in these materials can be modulated by tuning the modulus of the microgel particle building blocks. However, the effects of degradability and functionalization with different integrin-binding peptides on cellular responses has not been explored. In this work, RGDS functionalized and enzymatically degradable poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) microgels were annealed into MAP hydrogels via thiol-ene click chemistry and photopolymerization. During cell-mediated degradation, the microgel surfaces were remodeled to wrinkles or ridges, but the scaffold integrity was maintained. Moreover, cell spreading, proliferation, and secretion of extracellular matrix proteins were significantly enhanced in faster matrix metalloproteinase degrading (KCGPQGIWGQCK) MAP hydrogels compared to non-degradable controls after 8 days of culture. We subsequently evaluated paracrine activity by hMSCs seeded in the MAP hydrogels functionalized with either RGDS or c(RRETAWA), which is specific for α5β1 integrins, and evaluated the interplay between degradability and integrin-mediated signaling. Importantly, c(RRETAWA) functionalization upregulated secretion of bone morphogenetic protein-2 overall and on a per cell basis, but this effect was critically dependent on microgel degradability. In contrast, RGDS functionalization led to higher overall vascular endothelial growth factor secretion in degradable scaffolds due to the high cell number. These results demonstrate that integrin-binding peptides can modulate hMSC behavior in PEG-based MAP hydrogels, but the results strongly depend on the susceptibility of the microgel building blocks to cell-mediated matrix remodeling. This relationship should be considered in future studies aiming to further develop these materials for stem cell delivery and tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: Poly(ethylene glycol), hydrogel, human mesenchymal stem cells, cell-material interactions, integrin, matrix remodeling

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Efficacious stem cell therapies for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine require a biomaterial carrier to improve stem cell retention in degenerated sites and orchestrate tissue repair [1–3]. Understanding cell-material interactions is critical for designing effective stem cell delivery systems that promote specific cell behaviors, such as differentiation and paracrine secretion [4]. In general, it is appreciated that the biochemical and biophysical cues presented by biomaterials (i.e., bioactive molecules, topography, and substrate stiffness) can affect cell spreading, proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine secretion and, thus, should be considered in designing stem cell delivery systems [5–9]. However, the interplay between these cues can be complex and must also be considered.

Hydrogels have been a focal point in the field due to their ability to encapsulate stem cells and provide them with an extracellular matrix (ECM) like microenvironment [2, 10]. Myriad hydrogel platforms spanning natural and synthetic polymers and using a number of crosslinking strategies have been developed and reported. However, most work on hydrogels for stem cell delivery has focused on methods involving cell encapsulation within a nanoporous mesh, and recent research suggests that the isolated and restrictive nature of this microenvironment significantly alters cellular behavior [11–13]. For example, Caliari et al. reported that human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) encapsulated within 3D nanoporous hydrogels exhibit decreased spreading and decreased YAP nuclear localization as stiffness increases, which is opposite to the trends seen in 2D cultures [11]. These effects have been attributed to the nanoporous nature of the hydrogels, since stiffer hydrogels constitute more restrictive microenvironments to encapsulated cells. However, the effects are not limited to cell spreading and mechanosensing, as Qazi et al. found that when rat MSCs were encapsulated in nanoporous hydrogels the lack of cell-cell interactions resulted in decreased paracrine secretion, which could influence tissue regeneration outcomes [14].

Scaffolds assembled from hydrogel microspheres, or microgels, have recently emerged as a promising alternative platform to nanoporous hydrogels for stem cell delivery. In general, these materials are constructed by covalently linking microgels together (referred to as annealing) either via complementary functional groups or through the addition of bi-functional linker [15]. They can be injected into tissue defects non-invasively and in situ linked to form scaffolds that are inherently microporous with excellent pore interconnectivity. The average size of microgels typically ranges from 50–250 μm, which creates pores with several tens of microns in size. Thus, these materials have been termed microporous annealed particle (MAP) hydrogels. Importantly, cells can be incorporated during microgel annealing into MAP hydrogels and, in contrast to conventional hydrogels, cells are incorporated in the micropores between the spherical microgels rather than embedded in a nanoporous polymer mesh. Several recent studies have shown that cell spreading is superior in these microgel-based scaffolds compared to cells encapsulated in conventional nanoporous hydrogels [16–22]. In addition, because cells in MAP hydrogels interact with microgel surfaces and are not encapsulated, these materials provide a unique opportunity to leverage the rich body of knowledge regarding cell behavior in 2D environments to direct cellular behavior within these 3D scaffolds. Our previous work on poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) based MAP hydrogels annealed via thiol-ene click chemistry was the first to demonstrate this possibility, as we showed that hMSCs exhibit increased nuclear localization of Yes-associated protein (YAP) in MAP hydrogels made from stiff microgels, similar to what has been observed in 2D cultures [20].

To build on our prior work and develop materials that could be useful for hMSC delivery and bone tissue engineering, we are interested in understanding how the presentation of different integrin-binding peptides to hMSCs affects their behavior in PEG based MAP hydrogels [23, 24]. We are specifically interested in comparing the effects of a cyclized RRETAWA peptide (henceforth referred to as c(RRETAWA)), which targets α5β1 integrins, to the widely used RGDS motif that binds to many different integrins. c(RRETAWA) was originally identified from a heptapeptide phage display library for α5β1 specific targeting, and it was subsequently found to be effective in inducing hMSC osteogenic differentiation when added solubly [25–28]. The osteoinductive mechanism has been attributed to the upregulated PI3K/Wnt/β-catenin signaling by c(RRETAWA)-induced α5β1 integrin priming [29]. Importantly, Gandavarapu et al. reported that 2D PEG hydrogels functionalized with c(RRETAWA) induced hMSC osteogenic differentiation without the addition of soluble osteoinductive factors [30], providing further motivation for us to study c(RRETAWA) in MAP hydrogels. However, because the porosity of MAP hydrogels is relatively low (reported values range from 10–35 % [17, 20, 21]), we expected that the potential for cells to remodel their microenvironment might also be critical.

The objective of this study was to characterize hMSC growth in PEG-based MAP hydrogels and investigate the interplay between integrin-binding peptides and microgel degradability on hMSC behavior. To render the materials degradable, we synthesized enzymatically degradable PEG-peptide microgels using well established matrix metalloproteinase cleavable peptides. We then studied the effects of cell-mediated degradation on hMSC spreading, proliferation, and secretion of ECM in MAP hydrogels. The effects of cell-mediated degradation were also studied by characterizing the bulk integrity of the MAP hydrogel scaffolds as well as the surface morphology of the microgels. Similar experiments were performed for scaffolds functionalized with c(RRETAWA) rather than RGDS. Finally, we evaluated the interplay between degradability and integrin-binding via RGDS or c(RRETAWA) for modulating hMSC paracrine activity in MAP hydrogel scaffolds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Tetrafunctional PEG-norbornene macromers (PEG-Nb, 5 kDa, JenKem Technology) were synthesized from PEG-hydroxyl precursors via esterification with 5-norbornene-2-carboxylic acid (Alfa Aesar) and diisopropyl carbodiimide (Alfa Aesar) activation, as previously described by Jivan et al [31]. The polymers were dialyzed against deionized water prior to use, and the percent functionalization was higher than 95% via 1H NMR spectroscopy analysis. PEG-dithiol (PEG-DT, 3400 Da) crosslinker was purchased from Laysan Bio.. The cell adhesive peptide CGRGDS, enzymatically degradable peptide crosslinker KCGPQGIWGQCK, and CGPQGPAGQGCR were prepared via microwave- assisted standard Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis methods. Peptide identity was verified by matrix- assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI- TOF MS) analysis. The α5β1 integrin targeting peptide c(RRETAWA) was purchased from AAPPtec and was synthesized via an on-resin cyclization reaction of Ac-CAhxK(Alloc)RRETAWAE(ODmab), as previously described by Gandavarapu et al. [30]. Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) photoiniator was synthesized following the methods of Fairbanks et al. without modification and was verified by 1H NMR spectroscopy and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry prior to use [32].

2.2. Fabrication of MAP hydrogels

PEG microgels were fabricated by submerged electrospraying and thiol-ene click chemistry, as described previously [33]. Briefly, PEG-Nb, dithiol crosslinker, LAP, and cell adhesive peptide were mixed off-stoichiometrically to achieve a [SH]:[ene] ratio of 0.75:1. The working concentrations of PEG-Nb, di-thiol crosslinker, LAP, and cell adhesive peptide were 10 wt% (resulting in 73 mM norbornene groups), 26.87 mM, 1 mM, and 2 mM, respectively. PEG-DT, CGPQGPAGQGCR, and KCGPQGIWGQCK were used to prepare microgels with varying degradability (termed non-deg, slow-deg, and fast-deg, respectively) [34, 35]. These precursor solutions were electrosprayed under voltage of 4 kV, flow rate of 12 mL/h, and needle- to- grounded ring distance of 16 mm. The electrosprayed droplets were then collected in a light mineral oil bath with Span 80 (0.5 wt%) and photopolymerized using UV light (365 nm, 60 mW/cm2, 7 min, Lumen Dynamics Omnicure S2000 Series). The resulting microgels were centrifuged, washed one time with 30% ethanol, and then washed five times with phosphate buffered saline to remove mineral oil and surfactant. The microgels were swollen in 1X phosphate buffered saline at 4 °C overnight to reach equilibrium before use. After swelling, the microgels were imaged using light microscopy (Eclipse, TE2000-S, Nikon), and the size of microgels was measured from the images using Image-J software (n ≥ 150).

Next, these microgels were packed in a 6 mm diameter, 50 μL rubbery circular mold. Then, 8 μL of a solution containing PEG-DT and LAP in PBS was added to reach final concentration 2 mM and 1 mM, respectively, and the microgels were assembled into scaffolds by forming linkages between norbornene groups on the microgel surfaces via a secondary thiol-ene UV polymerization (Figure 1a, 365 nm, 10 mW/cm2, 3 min).

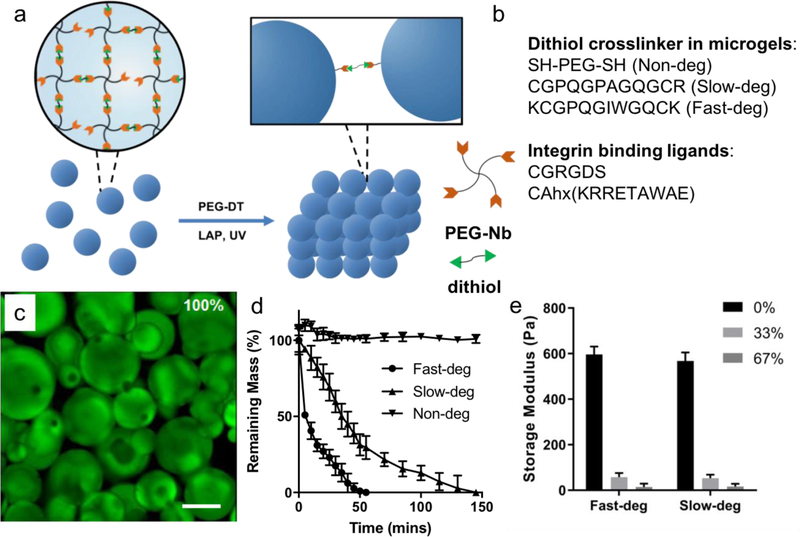

Figure 1.

Design and characterization of MAP hydrogels with varying degradability. a) A schematic of MAP hydrogels assembled from off-stoichiometric PEG microgels via a secondary thiol-ene photopolymerization. b) Peptide sequences designed as crosslinkers and cell-adhesive ligands to achieve varying degradability and integrin binding. c) A representative Z-stack projection image of MAP hydrogels labeled with Alexa Fluor 488- succinimidyl ester illustrating the internal porous structure. Scale bar is 100 μm. d) Degradation curves of non-deg, slow-deg and fast-deg MAP hydrogels in a 0.2 mg/mL collagenase solution at 37 °C. e) Storage modulus of slow-deg and fast deg MAP hydrogels after degradation with 0%, 33%, and 67% mass loss.

2.3. Characterization of MAP hydrogels

To characterize the degradability of MAP hydrogels, slow-deg and fast-deg scaffolds were soaked in 0.2 mg/mL collagenase B (Sigma) solution at 37 °C. The remaining scaffolds were weighed every 5 minutes for the first 50 minutes and every 20 minutes later on. In addition, the storage moduli of the MAP hydrogels after 33% and 67% mass loss were measured by oscillatory shear rheology (Physica MCR 301, Anton Paar) at 1% strain and 1 rad/s and compared to non-degraded scaffolds.

2.4. hMSC culture and seeding

Bone marrow derived hMSCs were acquired from the Institute of Regenerative Medicine at Texas A&M University. The hMSC identity was confirmed by immunophenotypic analysis on positive expression of CD29, CD44, CD146, CD166, HLA ABC, and negative expression of CD11b, CD79a [36]. hMSC culture media was α-Minimal essential medium (Gibco) supplemented with 20% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco), 50 U/mL penicillin (Gibco), and 50 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) at 5% CO2 and 37 °C in a humidified environment. Passage 3 cells, where 1 passage is equivalent to 8–9 population doublings, were used in this work. For hMSC seeding in MAP hydrogels, single- cell suspensions of hMSCs (5 μL) were mixed with microgels in the mold at a density of 250,000 cells per 50 μL scaffold along with the additional linker and LAP, and microgel assembly was performed by UV polymerization (365 nm, 10 mW/cm2, 3 min).

2.5. Cell spreading and proliferation

Samples were fixed after the desired culture time using 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Cytoskeletal staining was performed to determine the impact of scaffold degradability on cell spreading using rhodamine phalloidin (1:40, Invitrogen), and cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6- diamidino- 2- phenylindole (DAPI) (1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch). All the samples were imaged in a glass-bottomed petri dish (MarTek) by confocal microscopy (FV1000, Olympus).

At least three z-stack images were taken in different regions of each scaffold and each z-stack had a depth of 200 μm depth and 45 slices. The images were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH). For cell proliferation quantification, the 3D Objects Counter plugin was used to count the number of nuclei based on DAPI staining. The Voxel Counter plugin was used to measure the total cell volume in a z-stack based on phalloidin staining after thresholding. The average cell volume was then calculated by dividing the total cell volume by cell number.

2.6. Characterization after cell-mediation degradation

The diameter of MAP hydrogels before and after cell culture was measured by a caliper. To quantify the porosity of these scaffolds, high molecular weight tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate- labelled dextran (155 kDa, Sigma) was diffused into the MAP hydrogels and imaged by confocal microscopy (FV1000, Olympus). The overall porosity was calculated using ImageJ software (NIH) and the Voxel Counter plugin after thresholding. The storage moduli of fast-deg MAP hydrogels before and after cell culture were measured by oscillatory shear rheology (Physica MCR 301, Anton Paar) at 1% strain and 1 rad/s. To visualize the surface morphology after cell-mediated matrix remodeling, samples were collected after cell culture and decellularized by rinsing in 1X RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) overnight. The surface morphology was then imaged using environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM, Tescan Vega 3) in wet mode with a backscattering detector at 1 °C and 600 Pa.

2.7. ECM deposition

Proteins produced by cells were labelled based on fluorescent tagging of azidohomoalanine (AHA), as previously reported [37]. hMSC-laden MAP hydrogels were cultured in L-methionine, L-cystine and L-glutamine free high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Sigma) supplemented with 0.1 mM AHA (Invitrogen), 20% FBS, 0.2 mM cystine (Sigma), 100 μg/mL sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), 50 μg/mL ascorbate 2-phosphate, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. After the desired culture time, newly synthesized proteins were labeled with 25 μM dibenzocyclooctyne-PEG4-fluor 545 (Sigma) for 30 minutes and cell membranes were stained with the CellMask green plasma membrane stain (1:1000, Invitrogen). The samples were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Confocal microscopy (FV1000, Olympus) was used to image these samples at 20X and at least three z-stack images (100 μm depth with 45 slices) were taken in different regions of each scaffold. The protein channel was subtracted from cell membrane channel using image calculator in ImageJ to obtain only the ECM protein. The total ECM volume was then calculated using the Voxel Counter plugin in ImageJ.

Immunostaining for collagen type I and fibronectin after 8 days of culture was also performed. Prior to staining, the samples were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and incubated in blocking buffer containing 3% normal goat serum (Gibco) and 0.3% Triton-X 100 (Thermo Scientific) for 2 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against collagen type I (1:500, Abcam) and fibronectin (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were then added, followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor-488/647 IgG H&L (1:200, Abcam). Samples were counter stained with DAPI (1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Samples were imaged using confocal microscopy (FV1000, Olympus), and the volumes of collagen type I and fibronectin production were calculated using the Voxel Counter plugin in ImageJ.

2.8. Quantification of secretory activity

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits to evaluate the effect of scaffold degradability on stimulation of hMSC paracrine secretion by different integrin-binding peptides. Specifically, the angiogenic marker vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the osteogenic markers bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP2) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) were tested. In these experiments, hMSCs were cultured in culture media supplemented with 5 mM β-glycerophosphate and 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid. Media were collected after the desired culture time and protein concentrations were quantified following the commercial kit protocols (R&D Systems). The scaffolds were also lysed by 1X RIPA buffer, and the double stranded DNA content was determined by the Picogreen assay (Invitrogen) to normalize VEGF, BMP2, and OPG expression.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with at least three independent replicates. Results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to determine significant differences between groups. Significance is indicated by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.0001, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. MAP hydrogel characterization and degradation

PEG-based MAP hydrogels were synthesized similar to what we previously described [20]. The degradability of the MAP hydrogel scaffolds was tuned by introducing different dithiol crosslinkers during microgel fabrication (Figure 1b). The size of non-degradable microgels and degradable microgels were 266 ± 89 μm and 192 ± 90 μm, respectively (Figure S1). Linking the microgels together with a secondary thiol-ene reaction resulted in a microporous internal structure despite the high polydispersity of the microgels (Figure 1c). The linkages between the microgels were non-degradable PEG-DT to ensure that scaffold integrity was maintained during cell-mediated degradation. To evaluate the degradation rates, an accelerated degradation study was performed by immersing the MAP hydrogels in collagenase B solutions at 37 °C. The results confirmed that MAP hydrogels constructed from microgels with the tryptophan-containing peptide crosslinker (fast-deg group) degraded faster than those with proline-containing peptide crosslinker (slow-deg group; Figure 1d), which was comparable to previous investigations [35, 38], whereas MAP hydrogels from microgels with PEG-DT crosslinker (non-deg group) did not degrade. In addition, the shear storage moduli of the MAP hydrogels were characterized during degradation (Figure 1e). When they were degraded to the point of ~33% mass loss, the storage modulus was reduced by approximately ~90% in both the slow-deg and fast-deg groups. The modulus was further reduced after ~67% mass loss, and the MAP hydrogel scaffolds could be completely degraded over time.

3.2. Characterization of hMSC growth in RDGS and cRRETAWA functionalized MAP hydrogels

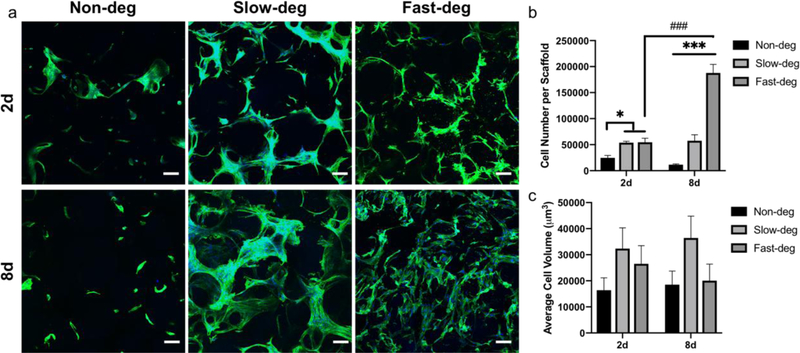

250,000 hMSCs were mixed with the microgels and incorporated into 50 μL MAP hydrogels during annealing via the secondary thiol-ene crosslinking reaction. Thus, they were located in the scaffold pores and were able to attach and spread on the microgel surfaces. We first evaluated hMSC spreading and proliferation in RGDS-functionalized MAP hydrogel scaffolds (Figure 2). Similar to previous results in the literature, hMSCs were able to spread around the microgels after 2 days due to the permissive environment in the scaffolds [16, 20]. However, the numbers of cells in both the slow-deg and fast-deg scaffolds were higher than in non-deg group after 2 days, indicating that cell-mediated degradation allowed for proliferation. This trend became more obvious after 8 days of culture, as further proliferation and an approximately 4-fold increase in cell number was observed in the fast-deg group. However, there was no significant increase in cell number in both the non-deg and slow-deg groups. In addition, in the slow-deg and fast-deg groups the cells were aggregated and formed a 3D cellular network, whereas they were isolated in the non-deg control group. Acellular spherical regions were no longer visible in the fast-deg 8-day samples, suggesting that cell-mediated degradation altered microgel morphology in this group.

Figure 2.

The effect of degradability on hMSC spreading and proliferation in RGDS-functionalized MAP hydrogels. a) Maximum intensity Z- projection of cytoskeleton staining of hMSCs cultured in MAP hydrogels after 2 and 8 days. Green represents F- actin and blue represents nuclei. Scale bars are 100 μm. b) Quantification of cell number. c) Quantification of cell volume. * comparison factor: degradability; # comparison factor: time. * indicates p < 0.05, *** and ### indicate p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

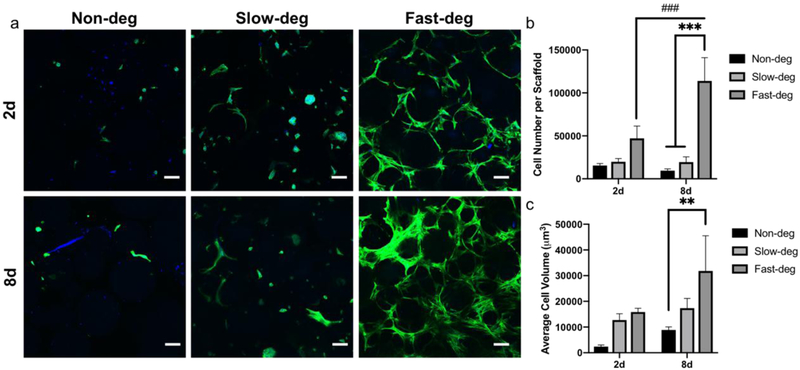

We also studied hMSC attachment, spreading and proliferation in c(RRETAWA)-presenting MAP hydrogel scaffolds (Figure 3). Abundant surface expression of α5 integrins by hMSCs has previously been reported [39], and we evaluated the integrin binding specificity of c(RRETAWA) was with an integrin blocking experiment (Figure S2). Importantly, when α5 integrins were blocked with an antibody, the number of cells in c(RRETAWA)-functionalized MAP hydrogels decreased by approximately 50%, whereas hMSCs were still able to attach normally within RGDS MAP hydrogels. These results are similar to those reported by Gandavarapu et al. [30], although our decrease in attachment to c(RRETAWA) after α5 blocking was not as dramatic. This difference is likely due to the greater difficulty of removing unattached cells from MAP hydrogels compared to 2D hydrogel slabs. Next, we characterized cell spreading in c(RRETAWA) functionalized MAP hydrogels, which was observed to be reduced compared to RGDS-presenting MAP hydrogels in non-deg and fast-deg groups after 2 days (Figure S3), likely because c(RRETAWA) binds only α5β1 integrins. Nevertheless, the hMSC spreading and proliferation trends with increasing degradability in c(RRETAWA) MAP hydrogels were similar to what was shown in RGDS scaffolds. While there were no significant differences between groups in cell number and volume after 2 days, the fast-deg scaffolds showed significantly higher cell number and volume after 8 days compared to non-deg and slow-deg groups. Interestingly, cells again only proliferated drastically from 2 to 8 days in the fast-deg scaffolds, similar to the results in the RGDS scaffolds. This result indicates that cell-mediated degradation is critical regardless of the integrin-binding peptide used.

Figure 3.

The effect of degradability on hMSC spreading and proliferation in c(RRETAWA)-functionalized MAP hydrogels. a) Maximum intensity Z- projection of cytoskeleton staining of hMSCs cultured in MAP hydrogels after 2 and 8 days. Green represents F- actin and blue represents nuclei. Scale bars are 100 μm. b) Quantification of cell number. c) Quantification of cell volume. * comparison factor: degradability; # comparison factor: time. ** indicates p < 0.01, *** and ### indicate p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

3.3. Cell-mediated matrix remodeling in MAP hydrogels

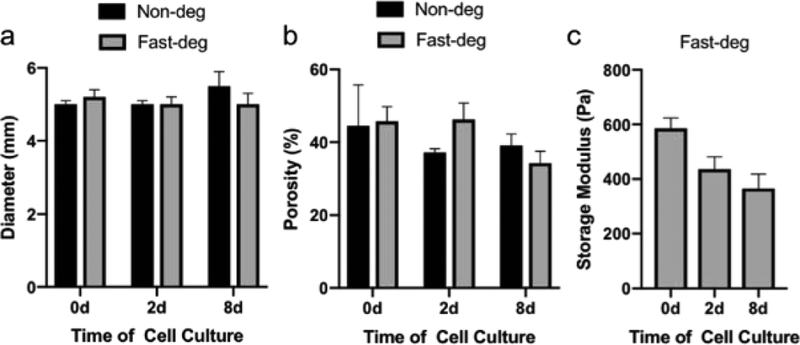

We further investigated the impact of degradability in RGDS-functionalized MAP hydrogels. First, to examine the extent of cell-mediated degradation in fast-deg MAP hydrogel scaffolds, we characterized bulk properties after cell culture and compared them to the non-deg control group (Figure 4). The diameter and porosity of the scaffolds did not change significantly after 8 days of culture in either the fast-deg or non-deg groups (Figure 4a and b), indicating cell-mediated degradation only occurred in a small portion of the materials. Furthermore, the storage moduli of the fast-deg scaffolds only dropped about ~30% after 8 days (Figure 4c). Considering ~33% mass loss could result in ~90% drop of modulus (Figure 1e), these results further confirmed that cell-mediated degradation of the MAP hydrogels was relatively limited after 8 days. Thus, these scaffolds could continue to play a supportive role to cells after long-term cell culture.

Figure 4.

Bulk properties of MAP hydrogels before and after cell-mediated degradation. a) Diameter and b) porosity of MAP hydrogels over cell culture. c) Storage modulus of fast-deg MAP scaffolds over cell culture.

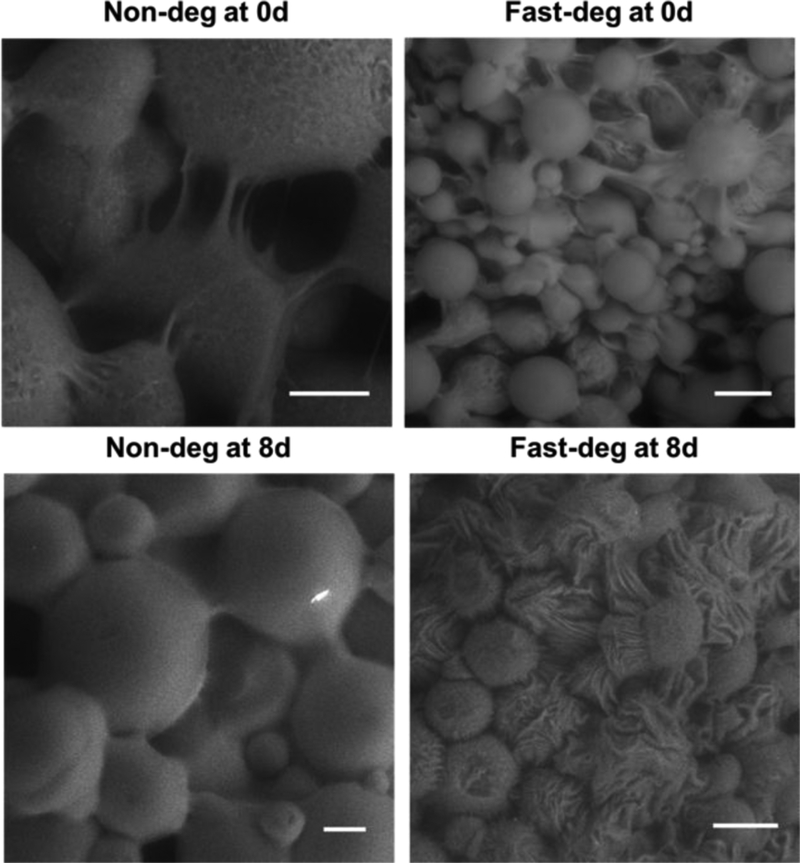

Next, we investigated the surface morphology of the microgels after cell-mediated degradation using ESEM (Figure 5). The microgel surfaces were smooth in the scaffolds prior to cell culture. Interestingly, fiber-like structures connecting microgels could be visualized, owing to the PEG-DT linkages between surface norbornene groups formed during the annealing process. After 8 days of cell culture, the MAP hydrogels were decellularized by washing in detergent. Non-deg scaffolds after cell culture maintained a smooth surface, although the linkages became less visible. In contrast, the surfaces of the fast-deg scaffolds appeared wrinkled after cell culture, indicating that cells were creating grooves as they remodeled their microenvironments to facilitate their spreading and proliferation. These results also indicated that cell-mediated matrix remodeling in the MAP hydrogels was limited to the microgel surfaces, again indicating that these scaffolds could continue to play a supportive role for cells despite cell-mediated degradation.

Figure 5.

ESEM images illustrating surface morphology of non-deg and fast-deg before and after cell-mediated matrix remodeling. Scale bars are 100 μm.

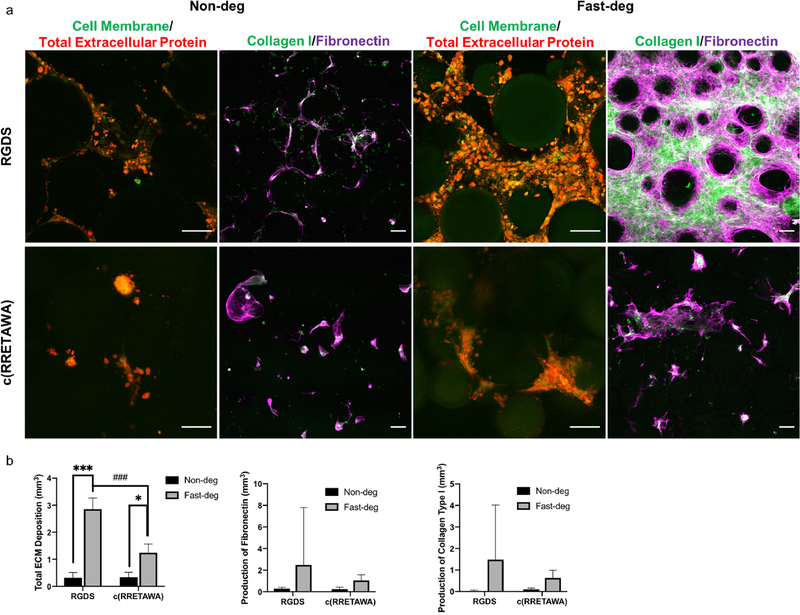

In addition to studying morphological changes to the microgels, we studied ECM deposition by the hMSCs in both non-deg and fast-deg RGDS and c(RRETAWA) functionalized MAP hydrogel scaffolds using a bio-orthogonal methionine analog labeling technique (Figure 6). ECM deposition was identified by subtracting labelled proteins from cell membrane staining and quantified. The results showed that the amount of ECM proteins synthesized after 2 days were similar for the non-deg and fast-deg groups (Figure S4). However, after 8 days of culture ECM deposition in RGDS-presenting fast-deg scaffolds accounted for roughly 5% of the volume of the entire scaffold, and the amount of ECM deposition was significantly higher compared to the non-deg scaffolds. These results correlate well with the hMSC spreading and proliferation data and indicate that, while microporosity alone can permit cellular spreading at early time points, cell-mediated degradation is critical over the longer term. Similar results of ECM deposition as an effect of degradability were observed in c(RRETAWA)-functionalized MAP hydrogels, but the amount of protein was significantly less compared to RGDS groups. Staining of specific ECM proteins, collagen type I and fibronectin further revealed that hMSCs produced fibrous ECM within the pores of MAP hydrogels in the fast-deg groups.

Figure 6.

ECM proteins, collagen type I and fibronectin synthesized by hMSCs in MAP hydrogels with varying degradability and integrin-binding peptides after 8 days of culture. a) Z-projection images from confocal microscopy. Scale bars are 100 μm. b) Quantification of total ECM protein per 50 μL MAP hydrogels. * comparison factor: degradability; # comparison factor: integrin-binding peptide. * indicates p < 0.05, *** and ### indicate p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

3.4. hMSC response to RGDS and c(RRETAWA) functionalized MAP hydrogels

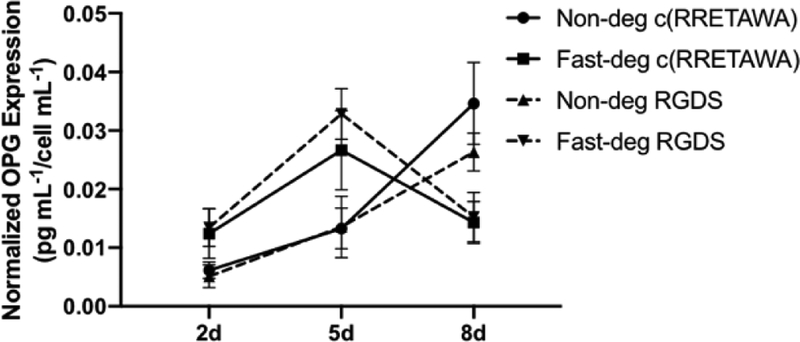

We studied the impact of cell-mediated degradation on the response of hMSCs to different integrin-binding peptides. We first examined the early osteogenic differentiation marker OPG in RGDS and c(RRETAWA) functionalized MAP hydrogel scaffolds. Importantly, the production of OPG normally peaks around 4 to 5 days during osteogenic differentiation in 2D cultures [40, 41]. In fast-deg scaffolds, OPG secretion peaked at 5 days as expected, while it did not peak until 8 days in the non-deg scaffolds (Figure 7). However, there was no significant difference in OPG secretion level between RGDS and c(RRETAWA) functionalized groups.

Figure 7.

hMSC expression of OPG in RGDS and c(RRETAWA)-functionalized MAP hydrogels with varying degradability after 2, 5, and 8 days of culture. Three-way ANOVA results: time (p < 0.0001), time×degradability (p < 0.0001), integrin-binding peptide×degradability (p < 0.05).

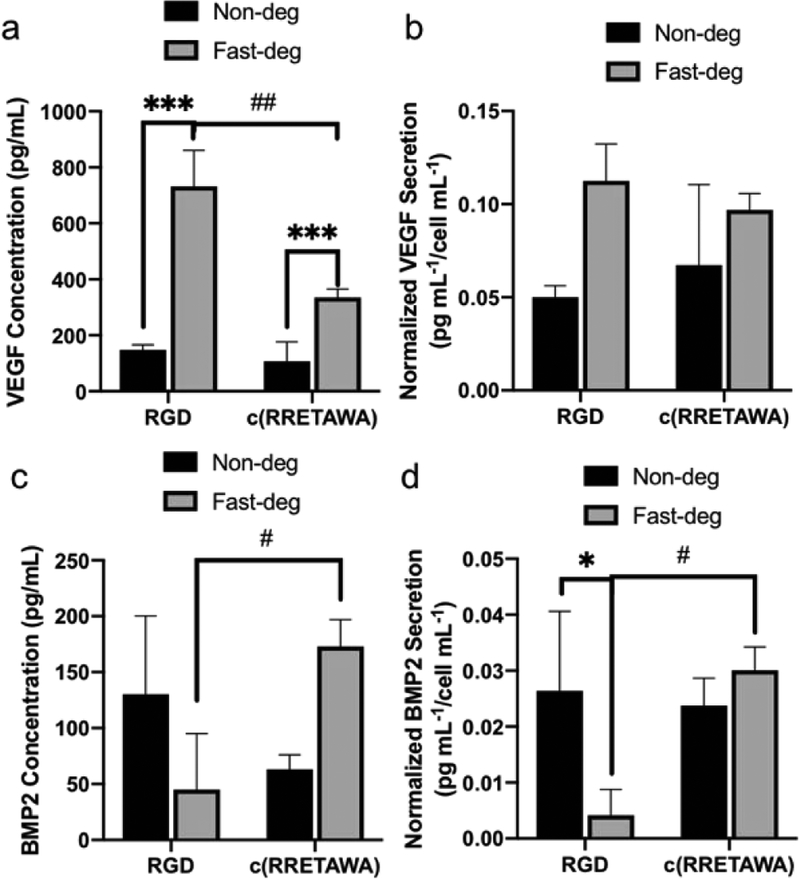

We also studied the effects on VEGF and BMP2 secretion at 8 days (Figure 8). In addition to overall protein production, the data was also analyzed after normalization to dsDNA to account for proliferation and evaluate cellular changes. Overall VEGF expression was upregulated in fast-deg MAP hydrogels and was higher with RGDS. However, this result was attributed to the higher cell number, as there were no significant differences between groups after normalization. In contrast, overall and normalized BMP2 expression was significantly higher in c(RRETAWA) functionalized fast-deg scaffolds than in RGDS functionalized fast-deg scaffolds. This result agrees with prior work reporting that c(RRETAWA) induces hMSC osteogenic differentiation [30]. However, the non-deg scaffolds did not show this difference, highlighting the importance of degradability.

Figure 8.

hMSC secretion of a, b) VEGF and c, d) BMP2 in MAP hydrogels functionalized with RGDS and c(RRETAWA) and with varying degradability after 8 days of culture. Data presented are both before and after normalization. * comparison factor: degradability; # comparison factor: integrin-binding peptide. * and # indicate p < 0.05, ## indicates p < 0.01, *** indicates p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

4. Discussion

MAP hydrogels are an emerging class of biomaterials that is receiving considerable attention for tissue repair and regeneration. The growing interest in MAP hydrogels stems from recent work demonstrating enhanced in vivo tissue regeneration compared to conventional nanoporous hydrogels [16, 42]. These materials are also an attractive stem cell delivery platform for tissue engineering [16]. Importantly, cells incorporated into MAP hydrogels during microgel annealing are able to spread and proliferate without requiring degradation of the surrounding matrix, as we previously showed [20]. However, the pore volume initially available to the cells is relatively low. Evidence suggests that larger pore spaces result in improved cell spreading and formation of a 3D cellular network [17, 20]. Thus, there is a need for degradable designs that allow for cell-mediated matrix remodeling.

To confer degradability, we fabricated MAP scaffolds from PEG-based microgels that were crosslinked with enzymatically degradable peptides. Two different peptides with varying susceptibility to enzymatic degradability (slow-deg and fast-deg) were used and compared to non-degradable controls (non-deg). MAP hydrogels constructed from these microgels exhibited the expected trends in degradability when immersed in collagenase (Figure 1). However, even the fast-deg group degraded relatively slowly in experiments with hMSCs and could likely play a supportive role for cells for a long-term period. This result was attributed to cell-mediated degradation only occurring on the microgel surfaces, leading to a low extent of degradation (Figure 4 and 5).

By culturing hMSCs in these MAP hydrogel scaffolds, we uncovered a crucial role for cell-mediated degradation in improving cell spreading and proliferation. There were negligible differences after 2 days of culture, as the inherent microporosity of the MAP hydrogels permitted initial cell spreading. However, hMSCs cultured in the fast-deg MAP hydrogel scaffolds in particular proliferated significantly from 2 to 8 days using both RGD and c(RRETAWA) integrin binding ligands, and the average cell volume did not drop (Figure 2 and 3). This result indicates that the pore space between microgels quickly becomes saturated for cell growth and cell-mediated degradation is needed to remodel surrounding matrix. Degradation may also increase the connectivity of the porous network by making larger openings between the pores.

In addition to the effects on cell growth, two notable changes to the cellular microenvironment were apparent when we compared fast-deg and non-deg MAP hydrogel scaffolds. First, topographical changes were observed, as the ESEM images revealed wrinkle structures on the surfaces of the microgels after cell-mediated degradation (Figure 5). This change could be important, as Guvendiren et al. previously manufactured various patterns of surface wrinkles on poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels and found that hMSCs cultured on lamellar patterned surfaces exhibited enhanced spreading and osteogenic differentiation compared to flat or hexagonal patterns [43]. Second, the hMSCs secreted more ECM proteins in fast-deg MAP hydrogel scaffolds compared to non-deg scaffolds (Figure 6). This difference likely impacted hMSC function, as Loebel et al. previously reported that cell-secreted nascent proteins act as an adhesive layer between cells and hydrogel matrix and cellular adhesion on the ECM layer is critical for hMSC spreading, mechanosensing, and osteogenic differentiation [44]. Several other works have also demonstrated cell-secreted ECM can play a pivotal role in hMSC differentiation [36, 45, 46].

While our findings on the effects of degradability are important and likely can be generalized to other MAP hydrogel platforms, we also sought to study the interplay between degradability and microgel functionalization with different integrin-binding peptides on hMSC behavior. We were specifically interested in comparing MAP hydrogels functionalized with RGDS and c(RRETAWA), as the latter has been shown to induce hMSC osteogenic differentiation [26, 29]. While most of the work on c(RRETAWA) has studied the effects of soluble peptide, Gandavarapu et al. showed that hMSCs grown on 2D PEG hydrogels functionalized with c(RRETAWA) differentiated down the osteogenic lineage without the addition of other soluble factors [30]. This prior work is particularly relevant to our study here because hMSCs incorporated during microgel annealing are not embedded in a hydrogel network and instead can interact with the 2D microgel surfaces, despite the 3D nature of the MAP hydrogels.

Importantly, we found that microgel degradability was critical for eliciting responses by hMSCs to the different integrin-binding peptides. Cellular OPG secretion, which is an early marker of osteogenic differentiation, peaked earlier in fast-deg MAP hydrogels with both RGDS and c(RRETAWA) functionalization (Figure 7). The effects of degradability and the integrin-binding peptides were further apparent when analyzing VEGF and BMP2 secretion. While no differences between the peptides were seen in non-deg control MAP hydrogels, overall VEGF secretion was increased in RGDS scaffolds whereas BMP2 secretion was increased overall and on a per cell basis in response to c(RRETAWA) scaffolds (Figure 8). While the up-regulated VEGF secrection mainly resulted from the high cell number in RGDS hydrogels, the higher BMP2 secretion in the c(RRETAWA) group agrees with the osteogenic effects of c(RRETAWA) reported previously [30]. The importance of degradability in elucidating these effects could be related to the changes in surface topography and ECM deposition in the degradable MAP hydrogels, but it could also be attributed to changes in cell-cell interactions, as cell-cell clustering was only observed in the fast-deg group (Figure 3). Previous work has demonstrated cell-cell interactions in biomaterial scaffolds regulates paracine secretion of hMSCs and promotes regenerative capacity [14, 47]. It is also possible that cell traction during degradation can result in matrix reorganization and clustering of integrin-binding ligands, which has been demonstrated to enhance osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs in dynamic bulk hydrogels previously [5, 48, 49].

5. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate that cell-mediated degradation in PEG-based MAP hydrogel scaffolds plays an important role in hMSC growth, ECM deposition, and responsiveness to different integrin-binding peptides. Thus, degradability is a critical variable that should be considered in future studies on cell-material interactions in MAP hydrogels. In addition, we found that in enzymatically degradable MAP hydrogels RGDS promoted higher overall VEGF secretion whereas the α5β1 binding peptide c(RRETAWA) promoted higher secretion of BMP-2 overall and on a per cell basis. Future work should aim to test if c(RRETAWA) functionalized MPA hydrogels can improve the efficacy of hMSC delivery for bone tissue engineering. Another particularly interesting possibility would be to leverage the differential effects of c(RRETAWA) and RGDS for bone tissue engineering by combining microgels presenting these two peptides into a single MAP hydrogel. Such an approach would exploit the modularity of MAP hydrogels and their unique ability to be constructed from multiple types of microgel building blocks, which is another important feature of these biomaterials that could potentially lead to superior tissue engineering outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance:

Microporous annealed particle (MAP) hydrogels are attracting increasing interest for tissue repair and regeneration and have shown superior results compared to conventional hydrogels in multiple applications. Here, we studied the impact of MAP hydrogel degradability and functionalization with different integrin-binding peptides on human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) that were incorporated during particle annealing. Degradability was found to improve cell growth, spreading, and extracellular matrix production regardless of the integrin-binding peptide. Moreover, in degradable MAP hydrogels the integrin-binding peptide c(RRETAWA) was found to increase osteogenic protein expression by hMSCs compared to RGDS-functionalized MAP hydrogels. These results have important implications for the development of a MAP hydrogel-based hMSC delivery system for bone tissue engineering.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21 AR071625. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability

The raw and processed data required to reproduce these findings are available from the authors upon request.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Madl CM, Heilshorn SC, Blau HM, Bioengineering strategies to accelerate stem cell therapeutics, Nature 557(7705) (2018) 335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Burdick JA, Mauck RL, Gerecht S, To serve and protect: hydrogels to improve stem cell-based therapies, Cell stem cell 18(1) (2016) 13–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rosales AM, Anseth KS, The design of reversible hydrogels to capture extracellular matrix dynamics, Nature Reviews Materials 1(2) (2016) 15012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang C, Varshney RR, Wang D-A, Therapeutic cell delivery and fate control in hydrogels and hydrogel hybrids, Advanced drug delivery reviews 62(7–8) (2010) 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chaudhuri O, Gu L, Klumpers D, Darnell M, Bencherif SA, Weaver JC, Huebsch N, Lee H.-p., Lippens E, Duda GN, Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity, Nature materials 15(3) (2016) 326–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee S, Stanton AE, Tong X, Yang F, Hydrogels with enhanced protein conjugation efficiency reveal stiffness-induced YAP localization in stem cells depends on biochemical cues, Biomaterials 202 (2019) 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cruz-Acuna R, Garcia AJ, Synthetic hydrogels mimicking basement membrane matrices to promote cell-matrix interactions, Matrix Biology 57 (2017) 324–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kirschner CM, Anseth KS, In situ control of cell substrate microtopographies using photolabile hydrogels, small 9(4) (2013) 578–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stanton AE, Tong X, Yang F, Extracellular matrix type modulates mechanotransduction of stem cells, Acta biomaterialia 96 (2019) 310–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Thakur A, Jaiswal MK, Peak CW, Carrow JK, Gentry J, Dolatshahi-Pirouz A, Gaharwar AK, Injectable shear-thinning nanoengineered hydrogels for stem cell delivery, Nanoscale 8(24) (2016) 12362–12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Caliari SR, Vega SL, Kwon M, Soulas EM, Burdick JA, Dimensionality and spreading influence MSC YAP/TAZ signaling in hydrogel environments, Biomaterials 103 (2016) 314–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Khetan S, Guvendiren M, Legant WR, Cohen DM, Chen CS, Burdick JA, Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels, Nature materials 12(5) (2013) 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Seidlits SK, Khaing ZZ, Petersen RR, Nickels JD, Vanscoy JE, Shear JB, Schmidt CE, The effects of hyaluronic acid hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties on neural progenitor cell differentiation, Biomaterials 31(14) (2010) 3930–3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Qazi TH, Mooney DJ, Duda GN, Geissler S, Biomaterials that promote cell-cell interactions enhance the paracrine function of MSCs, Biomaterials 140 (2017) 103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Riley L, Schirmer L, Segura T, Granular hydrogels: emergent properties of jammed hydrogel microparticles and their applications in tissue repair and regeneration, Current opinion in biotechnology 60 (2019) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Griffin DR, Weaver WM, Scumpia PO, Di Carlo D, Segura T, Accelerated wound healing by injectable microporous gel scaffolds assembled from annealed building blocks, Nature materials 14(7) (2015) 737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Caldwell AS, Campbell GT, Shekiro KM, Anseth KS, Clickable microgel scaffolds as platforms for 3D cell encapsulation, Advanced healthcare materials 6(15) (2017) 1700254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Rutte JM, Koh J, Di Carlo D, Scalable High- Throughput Production of Modular Microgels for In Situ Assembly of Microporous Tissue Scaffolds, Advanced Functional Materials 29(25) (2019) 1900071. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sheikhi A, de Rutte J, Haghniaz R, Akouissi O, Sohrabi A, Di Carlo D, Khademhosseini A, Microfluidic-enabled bottom-up hydrogels from annealable naturally-derived protein microbeads, Biomaterials 192 (2019) 560–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xin S, Wyman OM, Alge DL, Assembly of PEG Microgels into Porous Cell-Instructive 3D Scaffolds via Thiol- Ene Click Chemistry, Advanced healthcare materials 7(11) (2018) 1800160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sideris E, Griffin DR, Ding Y, Li S, Weaver WM, Di Carlo D, Hsiai T, Segura T, Particle hydrogels based on hyaluronic acid building blocks, ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2(11) (2016) 2034–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Truong NF, Kurt E, Tahmizyan N, Lesher-Pérez SC, Chen M, Darling NJ, Xi W, Segura T, Microporous annealed particle hydrogel stiffness, void space size, and adhesion properties impact cell proliferation, cell spreading, and gene transfer, Acta biomaterialia 94 (2019) 160–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Reyes CD, García AJ, α2β1 integrin- specific collagen- mimetic surfaces supporting osteoblastic differentiation, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 69(4) (2004) 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Keselowsky BG, Collard DM, García AJ, Integrin binding specificity regulates biomaterial surface chemistry effects on cell differentiation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(17) (2005) 5953–5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Koivunen E, Wang B, Ruoslahti E, Isolation of a highly specific ligand for the alpha 5 beta 1 integrin from a phage display library, The Journal of Cell Biology 124(3) (1994) 373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fromigué O, Brun J, Marty C, Da Nascimento S, Sonnet P, Marie PJ, Peptide- based activation of alpha5 integrin for promoting osteogenesis, Journal of cellular biochemistry 113(9) (2012) 3029–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mould AP, Askari JA, Humphries MJ, MOLECULAR BASIS OF CELL AND DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY-Molecular basis of ligand recognition by integrin a5b1. Specificity of ligand binding is determined by amino acid sequences in the second and third, Journal of Biological Chemistry 275(27) (2000) 20324–20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mould AP, Burrows L, Humphries MJ, Identification of amino acid residues that form part of the ligand-binding pocket of integrin α5β1, Journal of Biological Chemistry 273(40) (1998) 25664–25672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Saidak Z, Le Henaff C, Azzi S, Marty C, Da Nascimento S, Sonnet P, Marie PJ, Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediates osteoblast differentiation triggered by peptide-induced α5β1 integrin priming in mesenchymal skeletal cells, Journal of Biological Chemistry 290(11) (2015) 6903–6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gandavarapu NR, Alge DL, Anseth KS, Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on α5 integrin binding peptide hydrogels is dependent on substrate elasticity, Biomaterials science 2(3) (2014) 352–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jivan F, Yegappan R, Pearce H, Carrow JK, McShane M, Gaharwar AK, Alge DL, Sequential thiol–ene and tetrazine click reactions for the polymerization and functionalization of hydrogel microparticles, Biomacromolecules 17(11) (2016) 3516–3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Bowman CN, Anseth KS, Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2, 4, 6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility, Biomaterials 30(35) (2009) 6702–6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xin S, Chimene D, Garza JE, Gaharwar AK, Alge DL, Clickable PEG hydrogel microspheres as building blocks for 3D bioprinting, Biomaterials science 7(3) (2019) 1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Trappmann B, Baker BM, Polacheck WJ, Choi CK, Burdick JA, Chen CS, Matrix degradability controls multicellularity of 3D cell migration, Nature communications 8(1) (2017) 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Patterson J, Hubbell JA, Enhanced proteolytic degradation of molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels in response to MMP-1 and MMP-2, Biomaterials 31(30) (2010) 7836–7845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zeitouni S, Krause U, Clough BH, Halderman H, Falster A, Blalock DT, Chaput CD, Sampson HW, Gregory CA, Human mesenchymal stem cell–derived matrices for enhanced osteoregeneration, Science translational medicine 4(132) (2012) 132ra55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].McLeod CM, Mauck RL, High fidelity visualization of cell-to-cell variation and temporal dynamics in nascent extracellular matrix formation, Scientific reports 6 (2016) 38852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nagase H, Fields GB, Human matrix metalloproteinase specificity studies using collagen sequence- based synthetic peptides, Peptide Science 40(4) (1996) 399–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Martino MM, Mochizuki M, Rothenfluh DA, Rempel SA, Hubbell JA, Barker TH, Controlling integrin specificity and stem cell differentiation in 2D and 3D environments through regulation of fibronectin domain stability, Biomaterials 30(6) (2009) 1089–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Krause U, Harris S, Green A, Ylostalo J, Zeitouni S, Lee N, Gregory CA, Pharmaceutical modulation of canonical Wnt signaling in multipotent stromal cells for improved osteoinductive therapy, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(9) (2010) 4147–4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Krause U, Seckinger A, Gregory CA, Assays of osteogenic differentiation by cultured human mesenchymal stem cells, Mesenchymal Stem Cell Assays and Applications, Springer, 2011, pp. 215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nih LR, Sideris E, Carmichael ST, Segura T, Injection of microporous annealing particle (MAP) hydrogels in the stroke cavity reduces gliosis and inflammation and promotes NPC migration to the lesion, Advanced Materials 29(32) (2017) 1606471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Guvendiren M, Burdick JA, The control of stem cell morphology and differentiation by hydrogel surface wrinkles, Biomaterials 31(25) (2010) 6511–6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Loebel C, Mauck RL, Burdick JA, Local nascent protein deposition and remodelling guide mesenchymal stromal cell mechanosensing and fate in three-dimensional hydrogels, Nature Materials 18 (2019) 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Decaris ML, Leach JK, Design of experiments approach to engineer cell-secreted matrices for directing osteogenic differentiation, Annals of biomedical engineering 39(4) (2011) 1174–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kang Y, Kim S, Khademhosseini A, Yang Y, Creation of bony microenvironment with CaP and cell-derived ECM to enhance human bone-marrow MSC behavior and delivery of BMP-2, Biomaterials 32(26) (2011) 6119–6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ferreira SA, Faull PA, Seymour AJ, Tracy T, Loaiza S, Auner HW, Snijders AP, Gentleman E, Neighboring cells override 3D hydrogel matrix cues to drive human MSC quiescence, Biomaterials 176 (2018) 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, Rivera-Feliciano J, Mooney DJ, Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate, Nature materials 9(6) (2010) 518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tong X, Yang F, Sliding hydrogels with mobile molecular ligands and crosslinks as 3D stem cell niche, Advanced Materials 28(33) (2016) 7257–7263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.