Highlights

-

•

Seasonal influenza vaccine post-introduction evaluations (IPIEs) were conducted.

-

•

Critical implementation issues were highlighted across three middle-income countries.

-

•

Health workers have an important dual role in seasonal influenza vaccination.

-

•

Pregnant women vaccination should be prioritized and acceptance issues addressed.

-

•

The IPIE tool is available to countries for download on the WHO website.

Keywords: Seasonal influenza vaccination, Post-introduction evaluation, Middle-income countries, National Immunization Program, Program implementation, IPIE, Health worker vaccination

Abstract

Background

Vaccines for the control of seasonal influenza are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for use in specific risk groups, but their use requires operational considerations that may challenge immunization programs. Several middle-income countries have recently implemented seasonal influenza vaccination. Early program evaluation following vaccine introduction can help ascertain positive lessons learned and areas for improvement.

Methods

An influenza vaccine post-introduction evaluation (IPIE) tool was developed jointly by WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to provide a systematic approach to assess influenza vaccine implementation processes. The tool was used in 2017 in three middle-income countries: Belarus, Morocco and Thailand.

Results

Data from the three countries highlighted a number of critical factors: Health workers (HWs) are a key target group, given their roles as key influencers of acceptance by other groups, and for ensuring vaccine delivery and improved coverage. Despite WHO recommendations, pregnant women were not always prioritized and may present unique challenges for acceptance. Target group denominators need to be better defined, and vaccine coverage should be validated with vaccine distribution data, including from the private sector. There is a need for strengthening adverse events reporting and for addressing potential vaccine hesitancy through the establishment of risk communication plans. The assessments led to improvements in the countries’ influenza vaccination programs, including a revision of policies, changes in vaccine management and coverage estimation, enhanced strategies for educating HWs and intensified collaboration between departments involved in implementing seasonal influenza vaccination.

Conclusion

The IPIE tool was found useful for delineating operational strengths and weaknesses of seasonal influenza vaccination programs. HWs emerged as a critical target group to be addressed in follow-up action. Findings from this study can help direct influenza vaccination programs in other countries, as well as contribute to pandemic preparedness efforts. The updated IPIE tool is available on the WHO website http://www.who.int/immunization/research/development/influenza/en/index1.html.

1. Introduction

Influenza causes considerable morbidity worldwide and represents a public health problem with significant socioeconomic implications. Risk groups for influenza include those at increased risk of exposure to influenza virus as well as those at risk of developing severe disease. Recent global influenza estimates suggest that 290,000–650,000 deaths each year are due to seasonal influenza-associated respiratory diseases [1]. Mortality estimates available to date show the highest mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (2.8–16.5 deaths per 100,000 individuals) and in Southeast Asia (3.5–9.2 per 100,000 individuals), as well as among people aged 75 years or older (51.3–99.4 per 100,000 individuals) [2]. These data likely underestimate the true mortality burden, which also would include non-respiratory deaths attributed to influenza virus infection [3].

Internationally available vaccines for the control of seasonal influenza have the potential to prevent significant influenza morbidity and mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO), in 2012, made recommendations for annual influenza vaccination defining specific groups at risk of influenza disease and reconfirming the safety profile of influenza vaccines [4], [5]. Vaccination of pregnant women is considered to be a priority for countries initiating or expanding programs for seasonal influenza vaccination. Other risk groups recommended to be vaccinated are health workers (HWs), children aged 6–59 months, persons 65 years of age and older, and individuals with specific chronic medical conditions [4]. HW vaccination not only protects the individual, but also helps to reduce nosocomial outbreaks [6] and to ensure functioning health-care services during influenza epidemics and pandemics [7], [8]. Resistance to antivirals among influenza viruses is another concern that emphasizes the importance of influenza vaccination [9].

A review of all 194 WHO member states showed that 115 countries (59%) reported having a national influenza immunization policy in place in 2014 [10]. Despite these policy recommendations, seasonal influenza vaccination has a low relative uptake in all regions of the world when compared to other available vaccines and has not been adopted by most low- and middle-income countries. Recent assessments, e.g., in the European region, highlight large variations in national policies and coverage among member states [11]. While influenza vaccines were shown to provide value for money in both high-income as well as in certain low and middle-income countries [12], they are still used mainly in wealthier world regions such as the Americas, Europe and parts of the Western Pacific [13].

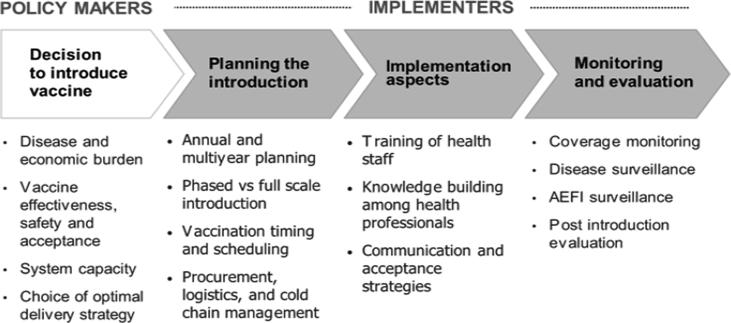

Compared with other vaccines, the use of influenza vaccines requires specific considerations related to implementation, including accommodating new formulations every year, choice of delivery sites (e.g., antenatal care clinics for pregnant women [14], nursing homes for the elderly), and timing of vaccine delivery based on variable influenza seasonality. The process of introducing influenza vaccine in a country needs to involve a large number of key stakeholders and to consider a range of interrelated issues (see Fig. 1). These include the collaboration of both the national immunization program (NIP) and the antenatal care (ANC) services, the involvement of HW occupational associations, and strong advocacy and communications efforts to ensure sufficient uptake of vaccines in the priority target groups, including those who are potentially hesitant. Conducting early vaccine post-introduction evaluations can help program managers ascertain positive lessons learned and areas for improvement to optimize their vaccination programs in their country’s context, using a generic tool tailored to specific antigens being evaluated [15].

Fig. 1.

Process of introducing an influenza vaccine into a national immunization program.

A post-introduction evaluation is usually combined with a NIP review [16], which assesses the strengths and weaknesses of the overall immunization program and provides evidence for improvements in program management and prioritization of activities. However, a post-introduction evaluation can also be useful as a standalone effort to assess the extent to which a specific vaccine introduction was successful and to recommend measures for improving operational procedures [15]. Specific to influenza, WHO, in collaboration with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), developed an Influenza Vaccine Post-Introduction Evaluation (IPIE) tool to support countries in their efforts to assess and optimize influenza vaccine program implementation [17]. The use of such a standardized tool can provide a systematic approach to compare findings and best practices across countries and regions. In this report, we present the experiences made with conducting an IPIE in three middle-income countries (MICs), and highlight some of the commonalities, challenges, and best practices in the implementation of influenza vaccination.

2. Methods

The IPIE tool provides an evaluation framework and a set of questionnaires, a standard schedule for conducting the assessment, guidance on the analysis of data collected, as well as templates for recommendations, presentation and reporting. An IPIE reviews all operational aspects and system components of vaccine use, including the availability of appropriate national policies and guidance, the quality of program management and service delivery, decision-making, planning and financing, HW capacity, vaccine management including cold chain and logistics, vaccine safety, data quality, monitoring and surveillance, as well as aspects of demand creation, communications and community acceptance.

The tool includes forms to be filled during the evaluation, templates for interviews with HWs and with immunization stakeholders, and guidance for health facility assessments including checklists for the observation of immunization sessions, vaccine storage areas and waste disposal arrangements. It also comprises interview forms for use with specific target populations, focusing on the quality of their interaction with the health services as well as on their acceptance of influenza vaccination. The tool is adaptable to each country’s context and to varying vaccine formulations and presentations and specifically reviews coordination needs among the NIP, ANC and other health programs involved in seasonal influenza vaccination.

To validate the IPIE process, in 2017, WHO, US CDC and partners, as part of a pilot project, supported the use of the tool in Belarus, Morocco and Thailand. These countries had been chosen to represent MICs in different WHO Regions (Europe, Eastern-Mediterranean and South East Asia) and at different stages of maturity of their influenza vaccination programs, as judged by the time since introduction of the seasonal influenza vaccine and the coverage achieved in the priority target groups.

The IPIE was performed at all levels of the health care system in these countries. National level interviews covered issues such as policies and service strategies, overall program management, NIP and ANC financing as well as partners’ and major stakeholders’ views. Three districts were selected based on performance (high, medium, and low performing) in each of three regions or provinces of a country and in turn, two health facilities were identified in each of these districts, one in an urban and the other in a rural location. Using the tool, health facilities were assessed and immunization sessions observed. In each health facility, at least two HWs and two vaccine recipients or their caregivers were interviewed. This provided an overall sample per country of 9 districts, 18 health facilities and 36 each of HWs and vaccine recipients.

IPIEs were conducted during five to seven days, with one day used for reviewing and adapting the tool to the country context, three to four days for team visits to selected regions, provinces and districts for carrying out interviews and observations and one to two days for data compilation and analysis, followed by a debriefing of the country Ministry of Health (MoH) and relevant stakeholders.

In November 2017, following the three evaluations, WHO held a two-day consultation in Geneva with representatives of the pilot evaluation countries and the IPIE team to discuss the appropriateness and relevance of the overall process and tool and derive lessons learned.

3. Results

In this section, we present results from the IPIE assessments conducted in Belarus, Morocco and Thailand across six major programmatic areas (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Country summaries of I-PIE assessments.

| Belarus | Morocco | Thailand | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policies and target groups | Seasonal influenza vaccination has been targeting some high-risk groups since 2002. In 2012, influenza vaccination was included in the national immunization schedule with additional groups targeted, including:

|

The country has a national plan for the prevention and control of influenza and SARI. The National Immunization Technical Advisory Group issued additional seasonal influenza vaccine recommendations in 2017.The following groups are targeted for immunization:

|

The country has a National Strategic Plan for Influenza Preparedness. The seasonal influenza vaccine program targets the following groups:

|

| Administrative vaccination coverage |

|

|

|

| Service delivery |

|

|

|

| Data recording Surveillance |

|

|

|

| Human resource capacity |

|

|

|

| Community acceptance |

|

|

|

| Other |

|

|

|

3.1. Policy and decision-making

In all three countries, the IPIE process identified national policies that had been established for the prevention and control of influenza, often in response to influenza outbreaks and potential pandemic threats, and reviewed the status of their implementation.

In Belarus, the national influenza control policy addresses coverage targets and corresponding budgets. Decisions for using the vaccine were based on national guiding principles and WHO recommendations more than on cost-benefit analyses. Morocco has a national plan for the prevention and control of influenza as well as a national influenza pandemic preparedness plan. The Moroccan National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) issued seasonal influenza vaccine recommendations and requested continuous disease burden data to be generated at the national level. In Thailand a national policy provides guidance for influenza control, but limited budgets led to insufficient vaccine supply for most target populations. Further economic evaluation has been requested by the Ministry of Health prior to deciding on the possible expansion of influenza vaccination.

3.2. Choice and coverage of target populations

In all pilot evaluation countries, a phased vaccine introduction was implemented, adding and modifying risk groups over time, usually starting with easier-to-reach priority groups such as HWs, persons with chronic diseases, and the elderly, and later including pregnant women and young children. Responding to local contexts, countries also vaccinated certain groups outside the globally recommended target groups, such as poultry cullers, security personnel, public services staff, pilgrims, obese or developmentally disabled persons.

All countries gave HW vaccination against influenza the highest priority due to infection control and pandemic preparedness considerations and as a result, coverage was highest among HWs (54–88%) compared with other target groups. Lower coverage in other groups resulted from lower acceptance and demand, e.g., in pregnant women in Morocco and Thailand, or insufficient vaccine supply despite good overall demand, e.g., in persons with chronic diseases in Thailand (Table 1).

3.3. Service delivery and vaccine management

Vaccine management and distribution systems were found to be adequate in all countries. Roles of the different responsible parties varied among the countries, with procurement, supply and distribution usually managed by the NIP whilst vaccine administration was sometimes under the responsibility of another health program (e.g., ANC implementing vaccination of pregnant women). Subnational vaccine demand forecasts varied in accuracy and sometimes could not prevent temporary vaccine stock-outs. Cold chains were well managed and maintained and vaccine wastage was generally low (<5%). In all countries, some ad-hoc vaccination of additional population groups was done, often in order to reduce vaccine wastage at the end of the influenza vaccination season.

In Belarus, appropriate demand forecasts, procurement, management and distribution resulted in sufficient vaccine stock reported at all levels. However, continuous electronic temperature monitoring systems in the cold chain were not in place everywhere and some of the cold chain equipment in use was not WHO-prequalified. In Morocco, vaccine distribution was particularly efficient, with distribution of all vaccines to regions and provinces within 2 days of vaccine arrival at the national storage facility in Casablanca. Deployment was based on microplans developed at health facilities for the number of doses needed for target groups served. Redeployment of unused doses from one facility to another was encouraged to reduce wastage. In Thailand, a mix of single and multi-dose vials allowed for the appropriate management of different vaccination session sizes. Cold chains were well managed by pharmacists and there is a vendor-managed inventory system for vaccine distribution, taking into account the need for the temporary seasonal increase in cold chain storage capacity.

3.4. Human resource capacity

Health staff were generally well-trained, experienced and knowledgeable, although in some facilities, HWs demonstrated more limited knowledge of the benefits and safety of influenza vaccines, possibly reflecting differences in training and supervision approaches. In all three countries, HWs appeared to play a central role in driving vaccine acceptance for target populations, being generally regarded as important sources of information on vaccination.

3.5. Data recording, reporting and surveillance

Across countries, doses administered at the sub-national level were regularly reported to the central level. In Belarus and Thailand, electronic databases are in use. While administrative coverage of influenza vaccination is being monitored everywhere, denominators were not always accurately known and data not regularly validated, e.g., through independent coverage surveys. Vaccination records for target groups not covered by the NIP were often insufficient (e.g. for pregnant women or the elderly) and home-based records were variably used among the three countries.

In Morocco the private sector, although actively involved in vaccination, only provides very limited data and information on influenza vaccination to the Ministry of Health. In Belarus, child records covering the early life course and including preventive and curative entries are only available at the facility level.

Routine influenza surveillance is ongoing in all countries to determine the burden of disease and to monitor influenza control activities. This surveillance includes both sentinel site and routine administrative reporting with clinical and laboratory components, with case-based surveillance implemented to a varying degree, but was at times constrained by a lack of sustained national funding.

3.6. AEFI surveillance

In all three countries, a reporting system for AEFI is in place with respective expert committees. In Morocco, AEFI surveillance is managed by a program different from the NIP and only 25% of health facilities are included in the scheme. In Thailand, online AEFI reporting systems are being set up in selected provinces. Overall, AEFI rates were lower than expected [18] and at times no AEFIs related to influenza vaccine had been reported for several years. Although WHO recommends that pregnant women should be vaccinated with inactivated influenza vaccine at any stage of their pregnancy, NIP directors noted fear of negative repercussions for national immunization programs should there be any AEFI related to influenza vaccination, even if coincidental. As a result, the policy followed in all three countries is to vaccinate pregnant women only during the 2nd and 3rd trimester, although this did not have much impact in Morocco or Thailand where coverage among pregnant women remains low.

3.7. Communications and community acceptance

A wide range of media were used in the three countries for the promotion of influenza vaccination and health communication including the provision of diverse education materials to improve community acceptance. HWs were seen to have an important double role in influenza vaccination in the three countries, one as priority recipients of vaccination and secondly, as primary information sources and proponents of influenza vaccination. However, in all three countries, there was wide variation in HW’s concerns about vaccine efficacy, and consequently, recommendations from HWs were not always consistent across target groups. At the same time, influenza vaccine uptake was also found to be related to personal beliefs and concerns among pregnant women and parents of young children, derived from other sources such as social media.

In Belarus, the IPIE assessment showed a general trust and a positive attitude towards the health care system. Exemplary community approaches using neighbourhood nurses and doctors appeared to increase vaccine demand. The country offered a large variety of complementary communication approaches with active involvement of the political leadership and the use of targeted materials for specific groups with assignment of staff to communicate with particular high-risk groups. In Morocco, on the other hand, there was only limited awareness in the general population of the influenza threat with lower overall demand. More recently, investigations into vaccine acceptance of pregnant women had to be terminated early due to the spread of anti-vaccine rumours which finally triggered the temporary cessation of all maternal immunization in the study region. Knowledge, attitudes, behaviour and practice studies are underway to better inform targeted influenza communication strategies. In Thailand, a variety of health education materials was available and village health volunteers and village leaders assisted with communications in their communities. There was good acceptance in the elderly and in persons with chronic disease, although demand was not always met because of vaccine supply shortages.

4. Discussion

The influenza vaccine post-introduction evaluations in these three countries gave rise to immediate improvements in their national influenza vaccination programs.

For example, in Belarus, IPIE findings resulted in greater attention to improvements in vaccine management, in part through the encouragement of local manufacturers of cold chain equipment to submit their products for WHO prequalification, and enhanced temperature monitoring. In addition, an existing e-Health data initiative was reinforced and health passports including influenza immunization are being incorporated into routine care for record-keeping and next visit reminders for parents and caretakers of young children. Plans were made to perform regular coverage surveys. The MoH also initiated the development of enhanced risk communications approaches to address potential vaccine hesitancy.

After the IPIE evaluation in Morocco, the country’s Department for Epidemiology and Disease Control revised its national plan for the prevention and control of influenza and initiated several awareness raising activities for decision-makers, considered additional strategies for educating HWs, and intensified the collaboration between the departments involved in implementing influenza vaccination.

In Thailand, after the IPIE was conducted, the country initiated further measures to improve coverage and reporting. Of particular note, Thailand significantly raised its commitment to the influenza vaccination program by increasing the quantity of purchased vaccine by 25% and began year-round immunization of pregnant women with an initial introduction in four provinces. Co-administration of tetanus toxoid-containing and influenza vaccines is being considered as an approach leading to increased coverage in pregnant women and to potential cost savings.

The IPIEs also identified areas of strength and areas for longer-term improvement of the countries’ influenza vaccination programs. For example, all three countries have a national policy on seasonal influenza vaccination, but the implementation of these policies varies.

The IPIEs showed that pregnant women, while recommended by WHO as highest priority risk group, were not always prioritized in the implementation of influenza vaccination, resulting in highly variable coverage rates, and highlighting the need for further sociocultural research on barriers to acceptance. Additionally, IPIE results suggested that increased integration of influenza vaccination into routine antenatal clinics, e.g., through improved collaboration between the NIP and ANC services could be a cost-saving approach to reach pregnant women. To assist countries in the optimization of influenza vaccination targeting pregnant women, the WHO guidance on how to introduce influenza vaccines for pregnant women could be a useful resource [14].

In contrast, all three countries had policies to prioritize HWs, based on pandemic preparedness considerations and had implemented specific HW influenza vaccination programs. Ensuring adequate coverage in this important target group also has the potential to affect vulnerable groups such as the immunocompromised, neonates (specifically in intensive care) and children [6], [19], [20], [21], and in the case of a severe outbreak, decrease overall disruption of health services. In all three countries, HWs – a group often insufficiently vaccinated and prone to vaccine hesitancy [22], [23], [24], [25], [26] – were identified as key influencers of program implementation. A recent study in Thailand showed that only 25% of pregnant women had received a HW recommendation for influenza vaccination and only 4% had received the vaccine during the current pregnancy [27]. Suggestions to improve uptake and trust in HWs included targeting key messages (e.g. ‘self-protection and protection of family and patients’) based on lessons learned in the pilot evaluation countries and elsewhere [28], [29], [30], [31]. In Thailand, an influenza control program including HW education, influenza screening and vaccination, and reinforcement of standard infection control policies resulted in fewer influenza infections and economic benefits to a hospital [32]. HWs should be empowered to drive communication efforts for existing and new target groups using a variety of innovative local approaches. A recent study on health education in older adults using educational videos in Bangkok showed significant positive impact on acceptance, knowledge and attitude towards influenza vaccination [33]. As seen in Belarus, paediatricians, obstetricians and other health professional groups can successfully transmit specific messages to relevant populations. The varying knowledge of the benefits and safety of influenza vaccines among HWs revealed by the IPIEs points to the need for better supporting them through intensified supervisory approaches and enhanced training and orientation at all levels. Based on a recent appraisal of evidence [34], WHO has developed a guidance document to support countries in strengthening or introducing influenza vaccination in HWs [35], [36].

Service delivery and vaccine management was found to be generally adequate, using the existing health infrastructure including cold chain and vaccine storage provisions. A recent modelling approach in Thailand, however, highlighted the risk of vaccine shortages during the influenza season due to wide-spread provincial to district transport capacity limitations [37]. Efforts should be made to meet the often high demand from the elderly and persons with chronic disease by ensuring sufficient supply to avoid potential negative repercussions for the entire program. In addition, roles and responsibilities between actors involved in influenza vaccination were at times unclear. The role of the private sector, specifically in urban settings, should be further evaluated to allow for a more coordinated delivery. To reduce costs and ease vaccine procurement processes, middle-income countries could also consider using the services of the UNICEF Supply Division.

In the area of data recording, reporting and surveillance, the IPIEs showed some limitations across countries. There is a need for more clearly estimating the numbers of persons in the target groups and to institute regular subnational coverage reporting, triangulating coverage data with the number of doses distributed and including private sector information, where applicable. Administrative coverage data should be validated through periodic surveys.

Influenza surveillance was well established in all countries with a mix of sentinel site and routine reporting systems, but at times insufficiently financed. High quality surveillance systems with minimum targets and appropriate quality indicators are vital for the planning and assessment of the effectiveness of vaccination programs. Furthermore, given the less well-defined seasonality of influenza in the tropics compared to temperate regions, surveillance in the former regions is also important to enable decisions about when best to vaccinate [38].

While AEFI surveillance systems were in place in all countries, the IPIEs showed that reporting frequency was lower than expected. The safety of vaccination in all trimesters of pregnancy remains an issue of concern to many HWs despite available WHO guidance [39]. Evidence-based information on the expected frequency of AEFI of influenza vaccines and AEFI reporting criteria will need to be reviewed and vaccine administration, AEFI management, causality assessment and response capacity enhanced, by including these issues prominently in HW trainings.

Community acceptance and potential vaccine hesitancy was shown to vary widely across the three countries, being lowest in Morocco and highest in Belarus. In Morocco, media controversies and rumours during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic were stated as the main argument for vaccine refusal [40]. A qualitative study on vaccine acceptability in Casablanca and Kenitra showed that low vaccine coverage was linked to unspecified fears including pandemic conspiracy theories, lack of knowledge of the vaccine and challenges in access to vaccination services. Decision-making among pregnant women was strongly influenced by HWs, family, community, mass media, and religious leaders, suggesting that broad communication efforts were needed to advocate for vaccination [41]. The WHO tool ‘Tailoring Immunization Programmes for Seasonal Influenza’ [42] can be helpful in guiding these communication approaches.

During the concluding IPIE consultation held in Geneva, senior officials of the participating countries felt that the IPIE process was useful to assess specific country contexts, to highlight programmatic issues and to identify measures to optimize seasonal influenza programs. The discussion also highlighted the increasingly important role that NITAGs should play in operationalizing vaccination and identifying specific influenza vaccine target groups, based on scientific evidence including local disease burden data. Participants of the consultation also suggested that policy makers would benefit from more clearly defining their operational research and information needs. Burden of disease estimates have informed some policy, e.g., in Thailand a recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that vaccination of children and adolescents (aged 2–17 years) with live-attenuated influenza vaccine was cost-effective [43], although cost-effectiveness was influenced by the match of the vaccine with the circulating influenza strains. In Belarus, on the other hand, surveillance for severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) in the WHO European region between 2009 and 2012 showed that the proportion of influenza-positive SARI cases was relatively low [44]. Additional burden of disease or cost-effectiveness considerations are expected to further strengthen national decision-making and policies.

While the small number of country experiences gathered through the pilot assessments prohibits broad generalization of the findings to other country contexts, the IPIE-related discussions among the participating countries helped to identify and address specific bottlenecks and the exchange of best practices. Further evidence gathered in additional countries may be useful to identify additional implementation issues and support countries to optimize their influenza immunization efforts.

5. Conclusion

The IPIE tool was found to be useful for delineating operational strengths and weaknesses of seasonal influenza vaccination programs. Taking into account lessons learned from the three countries, the IPIE tool has been further developed, including a version to be used on an Open Data Kit (ODK) platform, and is available to countries on the WHO influenza vaccines website at https://www.who.int/immunization/research/development/ipie_influenza_post_introduction_evaluation/en/.

Overall, the IPIE findings confirm similar observations in the literature and may thus warrant the following suggested actions depending on local contexts:

-

-

Policy making: Increased collaboration at the ministerial level (between departments in charge of seasonal influenza vaccination and of pandemic preparedness and response) and inclusion of relevant stakeholder groups (e.g., professional associations) may help strengthen policy development and implementation.

-

-

Target populations: Target groups should be more clearly defined to allow for better estimation of denominators. There is need to diversify and optimize approaches to vaccinate specific target groups, in particular HWs, to ensure adequate coverage.

-

-

Delivery and vaccine management: Clear roles and responsibilities between all actors involved, including the private sector, are required to ensure effective vaccine delivery.

-

-

Human resources: Identifying limited knowledge of the benefits and safety of influenza vaccines among HWs and intensified supportive supervisory approaches and training at all levels may help prevent and address capacity gaps.

-

-

Data recording, reporting and surveillance: Scientific rigour in data collection and analysis and sufficient support to sentinel surveillance and routine reporting systems should be ensured. AEFI surveillance will need to be enhanced.

-

-

Vaccine acceptance: HWs as both recipients and important promoters of vaccination should be further studied and supported with regards to their knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and practices related to seasonal influenza vaccination.

IPIE pilot implementation group

Country participants: Belarus: Iryna Hlinskaya, Republic Centre for Hygiene, Epidemiology and Public Health, Minsk; Sviatlana Khadasevich, Ministry of Health of the Republic of Belarus, Minsk. Morocco: Abderrahmane Maaroufi, Mohammed Youbi, Ezzine Hind, Imad Cherkaoui, Ministry of Health, Rabat. Thailand: Thanawadee Thantithaveewat, Pornsak Yoocharoen, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi.

US CDC experts: Kim Lindblade, Prabda Praphasiri and Josh Mott, US CDC, Nonthaburi, Thailand; Margaret McCarron, US CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA.

WHO experts: Bartholomew Dicky Akanmori, Technical Officer, Immunization and Vaccine Development, WHO Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo; Richard Brown, Programme Officer, WHO Country Office Thailand, Nonthaburi, Thailand; Julia Fitzner, Medical Officer, High Threat Pathogens, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Martin Friede, Coordinator, Initiative for Vaccine Research, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Viatcheslav Grankov, WHO Country Office, Minsk, Belarus; Myriam Grubo, Technical Officer, Health Systems and Innovation, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Joachim Hombach, Senior Health Adviser, Initiative for Vaccine Research, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Raymond Hutubessy, Technical Officer, Initiative for Vaccine Research, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Pernille Jorgensen, Technical Officer, Influenza and other Respiratory Pathogens, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark; Houda Langar, Regional Adviser, Vaccines Regulations and Production, WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, Cairo, Egypt; Jayantha Bandula L. Liyanage, Regional Adviser Immunization Systems Strengthening, Vaccine Preventable Diseases, WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia, New Delhi, India; Sk Md Mamunur Malik, Manager, Infectious Hazard Management WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, Cairo, Egypt; Ann Moen, Chief Influenza Preparedness & Response, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Alba Maria Ropero Alvarez, Advisor, Immunization, WHO Regional Office for the Americas, Washington, DC, USA; Yves Souteyrand, WHO Representative, WHO Representative's Office, Tunisia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the responsible senior staff of the Expanded Program for Immunization and of the Maternal and Child Health and Antenatal Care services in Belarus, Morocco, and Thailand for their willingness to collaborate with the study team on the gathering and review of data. The authors want to thank the senior officials of the National Health Security Office of Thailand, the Department for Epidemiology and Disease Control of Morocco and the Republican Centre for Hygiene, Epidemiology and Public Health in Belarus for their most valuable assistance and in-depth insights. The authors want to specifically acknowledge the assistance received from the IPIE Pilot Implementation Group in the development of the IPIE tool, the planning of the pilot program and the review and discussion of its findings.

Funding sources

The development and piloting of the IPIE tool was funded by a grant from the WHO Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR). The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the US CDC, which provides financial support to the WHO IVR (U50CK000431) and, through its collaborative agreement with the Thailand MOPH, for the Thailand evaluation.

Disclaimer

Philipp Lambach works for WHO; Susan Chu and Terri Hyde work for the US CDC. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the WHO or the US CDC.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.028.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization, News release: Up to 650 000 people die of respiratory diseases linked to seasonal flu each year; 2017.

- 2.Iuliano A.D. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan S. Challenges in reducing influenza-associated mortality. Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO/IVB Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper - November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012:461–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller-Stanislawski B. Safety of immunization during pregnancy: a review of the evidence of selected inactivated and live attenuated vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32(52):7057–7064. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sartor C. Disruption of services in an internal medicine unit due to a nosocomial influenza outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(10):615–619. doi: 10.1086/501981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horcajada J.P. A nosocomial outbreak of influenza during a period without influenza epidemic activity. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(2):303–307. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salgado C.D. Influenza in the acute hospital setting. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(3):145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maltezou H.C., Tsiodras S. Antiviral agents for influenza: molecular targets, concerns of resistance, and new treatment options. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10(10):1041–1048. doi: 10.2174/138945009789577972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortiz J.R. A global review of national influenza immunization policies: analysis of the 2014 WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on immunization. Vaccine. 2016;34(45):5400–5405. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Evaluation of seasonal influenza vaccination policies and coverage in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2014.

- 12.Ott J.J. Influenza vaccines in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(7):1500–1511. doi: 10.4161/hv.24704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palache A. Seasonal influenza vaccine provision in 157 countries (2004–2009) and the potential influence of national public health policies. Vaccine. 2011;29(51):9459–9466. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO/IVB/IVR. How to implement influenza vaccination of pregnant women. An introduction manual for national immunization programme managers and policy makers., V.a.B. Dept Immunization, Editor. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- 15.WHO/IVB/EPI. New Vaccine Post-Introduction Evaluation (PIE) Tool. World Health Organization; 2010.

- 16.WHO/IVB/EPI. A guide for conducting an expanded programme on immunization review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- 17.World Health Organization. Influenza Vaccination Program Evaluation - Brief Overview and Useful Tools. Available from: https://www.who.int/immunization/research/development/ipie_influenza_post_introduction_evaluation/en/; 2018.

- 18.World Health Organization. Observed rate of vaccine reactions - influenza vaccine 2012 [cited 2019 17 Sep]; Available from: https://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/initiative/tools/Influenza_Vaccine_rates_information_sheet.pdf.

- 19.Barlow G., Nathwani D. Nosocomial influenza infection. Lancet. 2000;355(9210):1187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunney R.J. An outbreak of influenza A in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(7):449–454. doi: 10.1086/501786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sagrera X. Outbreaks of influenza A virus infection in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21(3):196–200. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beguin C., Boland B., Ninane J. Health care workers: vectors of influenza virus? Low vaccination rate among hospital health care workers. Am J Med Qual. 1998;13(4):223–227. doi: 10.1177/106286069801300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halder S. Nosocomial influenza infection. Lancet. 2000;355(9210):1187–1188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray S.B., Skull S.A. Poor health care worker vaccination coverage and knowledge of vaccination recommendations in a tertiary Australia hospital. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26(1):65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smedley J. A survey of the delivery and uptake of influenza vaccine among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2002;52(5):271–276. doi: 10.1093/occmed/52.5.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wodi A.P. Influenza vaccine: immunization rates, knowledge, and attitudes of resident physicians in an urban teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(11):867–873. doi: 10.1086/502510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ditsungnoen D. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Thailand. Vaccine. 2016;34(18):2141–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollmeyer H. Review: interventions to increase influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(4):604–621. doi: 10.1111/irv.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann F. Influenza vaccination of healthcare workers: a literature review of attitudes and beliefs. Infection. 2006;34(3):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s15010-006-5109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maltezou H.C., Tsakris A. Vaccination of health-care workers against influenza: our obligation to protect patients. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5(6):382–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinrich-Morrison K. An effective strategy for influenza vaccination of healthcare workers in Australia: experience at a large health service without a mandatory policy. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:42. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0765-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apisarnthanarak A. Reduction of seasonal influenza transmission among healthcare workers in an intensive care unit: a 4-year intervention study in Thailand. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(10):996–1003. doi: 10.1086/656565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worasathit R. Health education and factors influencing acceptance of and willingness to pay for influenza vaccination among older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:136. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkin D.C. A rapid evidence appraisal of influenza vaccination in health workers: an important policy in an area of imperfect evidence. Vaccine X. 2019;2 doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherian T. Factors and considerations for establishing and improving seasonal influenza vaccination of health workers: report from a WHO meeting, January 16–17, Berlin, Germany. Vaccine. 2019;37(43):6255–6261. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. How to implement seasonal influenza vaccination of health workers ed. IVB/IVR. Geneva; 2019.

- 37.Assi T.M. How influenza vaccination policy may affect vaccine logistics. Vaccine. 2012;30(30):4517–4523. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caini S. Temporal patterns of influenza A and B in tropical and temperate countries: what are the lessons for influenza vaccination? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Safety of Immunization during pregancy. A review of the evidence. Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, Editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

- 40.Tagajdid M.R. Factors influencing uptake of influenza vaccine amongst healthcare workers in a regional center after the A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic: lessons for improving vaccination rates. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2011;23(4):249–254. doi: 10.3233/JRS-2011-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohiniva A.L. A qualitative study of vaccine acceptability and decision making among pregnant women in Morocco during the A (H1N1) pdm09 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.WHO/EURO. Tailoring immunization programmes for seasonal influenza (TIP FLU). Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO EURO; 2015.

- 43.Meeyai A. Seasonal influenza vaccination for children in Thailand: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2015;12(5):e1001829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001829. discussion e1001829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meerhoff T.J. Surveillance for severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) in hospitals in the WHO European region - an exploratory analysis of risk factors for a severe outcome in influenza-positive SARI cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0722-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.