Abstract

Background

Aedes albopictus is naturally infected with Wolbachia spp., maternally transmitted bacteria that influence the reproduction of hosts. However, little is known regarding the prevalence of infection, multiple infection status, and the relationship between Wolbachia density and dengue outbreaks in different regions. Here, we assessed Wolbachia infection in natural populations of Ae. albopictus in China and compared Wolbachia density between regions with similar climates, without dengue and with either imported or local dengue.

Results

To explore the prevalence of Wolbachia infection, Wolbachia DNA was detected in mosquito samples via PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene and the surface protein gene wsp. We found that 93.36% of Ae. albopictus in China were positive for Wolbachia. After sequencing gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ, fbpA and wsp genes of Wolbachia strains, we identified a new sequence type (ST) of wAlbB (464/465). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that wAlbA and wAlbB strains formed a cluster with strains from other mosquitoes in a wsp-based maximum likelihood (ML) tree. However, in a ML tree based on multilocus sequence typing (MLST), wAlbB STs (464/465) did not form a cluster with Wolbachia strains from other mosquitoes. To better understand the association between Wolbachia spp. and dengue infection, the prevalence of Wolbachia in Ae. albopictus from different regions (containing local dengue cases, imported dengue cases and no dengue cases) was determined. We found that the prevalence of Wolbachia was lower in regions with only imported dengue cases.

Conclusions

The natural prevalence of Wolbachia infections in China was much lower than in other countries or regions. The phylogenetic relationships among Wolbachia spp. isolated from field-collected Ae. albopictus reflected the presence of dominant and stable strains. However, wAlbB (464/465) and Wolbachia strains did not form a clade with Wolbachia strains from other mosquitoes. Moreover, lower densities of Wolbachia in regions with only imported dengue cases suggest a relationship between fluctuations in Wolbachia density in field-collected Ae. albopictus and the potential for dengue invasion into these regions.

Keywords: Aedes albopictus, Wolbachia, Infection, MLST genes, Phylogenetic analysis, Dengue virus

Background

Dengue is a rapidly spreading infectious disease transmitted between humans by mosquitoes of the genus Aedes. It is estimated that 400 million people are infected with dengue per year worldwide. To date, no effective vaccine or curative antiviral drug is available to prevent or treat dengue fever [1]. Thus, vector control has become the primary tool for dengue intervention. In China, Aedes albopictus is the primary dengue vector, and was responsible for the epidemic in 2014 resulting in approximately 47,000 infections. Use of insecticides is effective in controlling dengue, but is often prohibitively expensive, unsustainable and environmentally unfriendly. Other approaches require constant interventions that are expensive and difficult to implement in urban areas [2]. In recent years, the Wolbachia-based approach has been proposed as a new vector control strategy [3].

Wolbachia is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria that infect arthropods and filarial nematodes. It has been recently estimated that ~ 40% of arthropod species and ~ 28.1% of mosquitoes are infected with Wolbachia [4, 5]. These alpha-proteobacteria endosymbionts are transmitted vertically through host eggs and alter host biology in diverse ways, including reproductive manipulations such as feminization, parthenogenesis, male killing and sperm-egg incompatibility [6–8]. Furthermore, a large number of studies have shown that Wolbachia have an effect on the host’s olfactory sense, immunity and lifespan [9, 10]. After Hedges et al. [11] and Teixeira et al. [12] reported that Wolbachia can protect Drosophila flies from viral infections, a novel control strategy was proposed using Wolbachia to control or limit the spread of mosquito-transmitted diseases such as dengue and malaria. A Wolbachia strain from Drosophila could be transferred into Aedes aegypti; releasing this transinfected mosquito may result in invasion and spread of Wolbachia into wild mosquito populations [13]. Additionally, these strains also interfere with the host’s reproduction, inhibit viral replication and reduce adult lifespan [14].

wMel-transinfected Ae. aegypti populations have already been established and successfully released in Australia [3, 15]. Subsequently, other countries and regions in which Ae. aegypti is the main vector of dengue, such as Vietnam, Brazil, Colombia and Indonesia, have also started to release wMel-infected mosquitoes [16, 17]. In different parts of China, especially the south (e.g. Guangdong), Ae. albopictus is the major vector of dengue. Thus, studies are currently underway to apply a Wolbachia strain, wPip, from a Culex mosquito species to control Ae. albopictus. Although the theory and technology are already established, the prevalence and characteristics of Wolbachia in natural Ae. albopictus populations are poorly understood.

Aedes albopictus carries Wolbachia superinfections with two strains, wAlbA and wAlbB. In a given region Ae. albopictus harbors only single wAlbA infections, and field-collected mosquitoes with single wAlbB infections were identified in Changsha, Chenzhou and Wuhan, as has been previously reported in Guangzhou [18]. Studies of natural Wolbachia infections of Ae. albopictus in China have been much less conclusive and were mainly based on the wsp gene. In addition, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), a robust classification system that accomplishes strain typing based on variation in five conserved housekeeping genes (ftsZ, gatB, coxA, hcpA and fbpA), was applied in mosquitoes singly infected with supergroup A or B Wolbachia [19]. No studies have applied MLST to assess co-infection with supergroups A and B Wolbachia in Ae. albopictus. In previous studies, quantification of Wolbachia in mosquitoes aimed to examine the direct association between Wolbachia and virus in vivo, and several studies were carried out to understand virus-Wolbachia relationships in natural mosquito populations [20, 21].

The present study aimed to determine the natural prevalence of Wolbachia infections and to investigate differences in Wolbachia infection among five different climatic regions. MLST and wsp analyses were applied to characterize Wolbachia strains and estimate the phylogenetic relationships between Wolbachia strains in field-collected Ae. albopictus from China. Our findings illuminate the characteristics and prevalence of Wolbachia in natural populations of Ae. albopictus in China.

Methods

Mosquito sampling

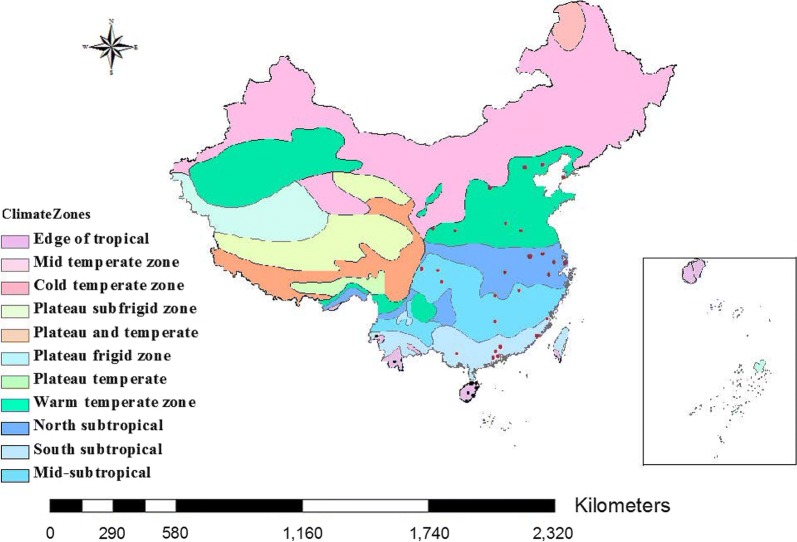

According to the geographical distribution and climatic characteristics of Ae. albopictus in China, we selected 6–8 sites in each of five climate zones of Ae. albopictus distribution. Samples were collected at each site according to a five-point method. In this study, a total of 704 adult Ae. albopictus (190 males and 514 females) were collected from 34 districts between June and October 2014 (Table 1). For analysis of prevalence, sampling locations were placed into five climate groups as defined in the Chinese Climatic Regions, based on the following climate classifications: Edge of tropical; South subtropical; Mid-subtropical; North subtropical; and Warm temperate zone (Fig. 1) [22]. BG traps, human baited net traps and manual aspirators were used to catch adult mosquitoes. Pipettes and dippers were used for capturing larvae or pupae from different containers at each site. The same operation was repeated at least five times in each location to reduce sampling error. Sampling staff were well protected whilst catching adults to avoid mosquito bites. The collected larvae and pupae were reared to adults and supplemented with yeast extract. The adults collected in the field were examined morphologically to confirm whether they were Ae. albopictus [23]. Samples were stored at − 80 °C in individual tubes containing 95% ethanol until DNA extraction.

Table 1.

Sample information

| Climate zone | District | Coordinates | No. of samples | ♀ | ♂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge of tropical | Wenchang | 19.57°N, 110.80°E | 33 | 25 | 8 |

| Wanning | 18.81°N, 110.39°E | 21 | 16 | 5 | |

| Haikou | 20.02°N, 110.20°E | 33 | 21 | 12 | |

| Qiongzhong | 19.04°N, 109.83°E | 18 | 10 | 8 | |

| Sanya | 18.25°N, 109.51°E | 37 | 22 | 15 | |

| Jinghong | 22.01°N, 100.77°E | 34 | 23 | 11 | |

| Dehong | 24.43°N, 98.59°E | 21 | 19 | 2 | |

| South subtropical | Nanning | 22.82°N, 108.36°E | 25 | 17 | 8 |

| Foshan | 23.02°N, 113.11°E | 12 | 10 | 2 | |

| Guangzhou | 23.41°N, 113.23°E | 33 | 19 | 14 | |

| Jiangmen | 22.50°N, 113.40°E | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Zhongshan | 22.40°N, 112.72°E | 20 | 12 | 8 | |

| Fuzhou | 26.08°N, 119.30°E | 24 | 18 | 6 | |

| Xiamen | 24.59°N, 118.10°E | 24 | 15 | 9 | |

| Mid-subtropical | Changsha | 28.21°N, 112.99°E | 25 | 11 | 14 |

| Chenzhou | 25.77°N, 113.01°E | 18 | 13 | 5 | |

| Nanchang | 28.68°N, 115.86°E | 22 | 16 | 6 | |

| Chengdu | 30.66°N, 104.07°E | 18 | 14 | 4 | |

| Nanchong | 30.49°N, 106.04°E | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Chongqing | 29.57°N, 106.55°E | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

| North subtropical | Hefei | 31.82°N, 117.23°E | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Nanjing | 32.05°N, 118.79°E | 27 | 20 | 7 | |

| Shanghai | 31.23°N, 121.48°E | 31 | 24 | 7 | |

| Wuhan | 30.35°N, 114.17°E | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Wuxi | 31.34°N, 120.18°E | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Hangzhou | 30.18°N, 119.5°E | 26 | 18 | 8 | |

| Warm temperate zone | Beijing | 39.77°N, 116.66°E | 30 | 24 | 6 |

| Shangqiu | 34.17°N, 116.20°E | 13 | 13 | 0 | |

| Taiyuan | 37.98°N, 112.32°E | 31 | 31 | 0 | |

| Xian | 34.17°N, 108.21°E | 18 | 18 | 0 | |

| Tangshan | 39.96°N, 118.81°E | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Kaifeng | 34.80°N, 114.27°E | 15 | 12 | 3 | |

| Tianshui | 34.71°N, 105.47°E | 22 | 20 | 2 | |

| Dalian | 38.94°N, 121.40°E | 21 | 15 | 6 |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of sampling sites for Ae. albopictus. Black, red, pink, purple, and brown dots are the sample sites at the Edge of tropical, South subtropical, Mid-subtropical, North subtropical and Warm temperate zones, respectively

DNA extraction and prevalence of Wolbachia infection

To assess the prevalence of Wolbachia infection, 2–37 Ae. albopictus were used from each population to extract total DNA. After drying the Ae. albopictus for several minutes, they were washed three times in ddH2O. DNA was then individually extracted using a DNAeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Two 16S rDNA primers and four wsp-specific primers, WAF/WAR and WBF/WBR, were used to detect Wolbachia DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the DNA of a single mosquito as a template [24, 25]. The 28S rRNA gene was used to assess the quality of DNA extraction and the cox1 mitochondrial gene was sequenced to exclude mosquitoes that were not Ae. albopictus. The full-length cox1 gene was amplified using four primers, cox1F/cox1R and cox1f/cox1r (Table 2). PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μl containing 2 μl of DNA, 11 μl of ddH2O, 1 μM of each primer and 10 μl of SuperMix. The temperature was cycled at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 37 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and then a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. DNA extracted from Wolbachia-infected Ae. albopictus was used as a positive control and ddH2O was used as a negative control. PCR products were run on 1% agarose gels and the cox1 PCR products were sequenced directly.

Table 2.

Primers for amplification and sequencing

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Annealing T (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rDNA | 16SF | CGGGGGAAAAATTTATTGCT | 55 |

| 16SR | AGCTGTAATACAGAAAGTAAA | ||

| wAlbA-wsp | WAF | CCAGCAGATACTATTGCG | 55 |

| WAR | AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA | ||

| wAlbB-wsp | WBF | AAGGAACCGAAGTTCATG | 55 |

| WBR | AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA | ||

| wsp | 81 | TGGTCCAATAAGTGATGAAGAAAC | 53 |

| 691 | AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA | ||

| FtsZ | ftsZ-F | TACTGACTGTTGGAGTTGTAACTAAGCCGT | 58 |

| ftsZ-R | TGCCAGTTGCAAGAACAGAAACTCTAACTC | ||

| 28S rRNA | 28F | TACCGTGAGGGAAAGTTGAAA | 55 |

| 28R | AGACTCCTTGGTCCGTGTTT | ||

| cox1 | cox1F | TTTACAATTTATCGCCTAAACTTC | 55 |

| cox1R | CATTGCACTAATCTGCCATA | ||

| cox1f | GGGGGAGACCCTATTTTATA | 55 | |

| cox1r | TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA | ||

| wAlbAq-wsp | qAF | GGGTTGATGTTGAAGGAG | 55 |

| qAR | CACCAGCTTTTACTTGACC | ||

| wAlbBq-wsp | qBF | ACGTTGGTGGTGCAACATTTG | 58 |

| qBR | TAACGAGCACCAGCATAAAGC | ||

| RPS | RPS6-F | CGTCGTCAGGAACGTATTCG | 55 |

| RPS6-R | TCTTGGCAGCCTTGACAGC |

Note: Primers cox1f/cox1r were used for sequencing

Abbreviation: T, temperature

Cloning and sequencing of wsp and MLST genes

The WSP loci were amplified with wsp (Wolbachia surface protein gene) primers to confirm multiple infections. PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μl containing 2 μl of DNA, 11 μl of ddH2O, 1 μM of each primer and 10 μl of SuperMix. The temperature was cycled at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 37 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and then a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min.

The five MLST loci were amplified according to previously published protocols (http://pubmlst.org/Wolbachia/). PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μl containing 2 μl of DNA, 11 μl of ddH2O, 1 μM of each primer and 10 μl of SuperMix. The temperature was cycled at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 37 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, Tm (Tm values for each primer pair are shown in Table 2) for 45 s and 72 °C for 90 s, and then a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. For co-infected samples, the coxA and ftsZ genes were amplified using primers coxA_F1 (5′-TTG GRG CRA TYA ACT TTA TAG-3′) and coxA_R1 (5′-CT AAA GAC TTT KAC RCC AGT-3′), and ftsZ-F (5′-TAC TGA CTG TTG GAG TTG TAA CTA AGC CGT-3′) and ftsZ-R (5′-TGC CAG TTG CAA GAA CAG AAA CTC TAA CTC-3′), respectively. For the fragment of coxA, primers for B-specific MLST protocols for AB infections were not used in our study, and ftsZ fragments were not long enough to be amplified by A-specific and B-specific primers. Fragments of coxA, ftsZ and wsp with the expected sizes were excised from the gel and purified using the Pure Yield™ Plasmid Miniprep System (Promega, Madison, USA). The purified DNA was ligated into pEASY-T5 Zero Cloning vector (Trans) and then transferred to Trans1-T1 phage resistant chemically competent cells (Trans). Putative clones of expected fragments were submitted for DNA sequencing. For all three kinds of fragments, at least eight clones were sequenced for each mosquito using both M13 forward and reverse primers, with three individuals being analyzed for each geographical population.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

All newly generated sequences for wsp, cox1, gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ, fbpA genes were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KU738304-KU738385, KU738386-KU738431, MK809569-MK809640, MK809709-MK809776, MK809845-MK809912, MK809777-MK809844, MK809641-MK809708, respectively. According to the MLST protocol, the sequences of gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ, fbpA and wsp were submitted to the PubMLST database for sequence typing, generating a MLST allelic profile and a WSP hypervariable region (HVR) profile. Strain and host information were deposited in the MLST database.

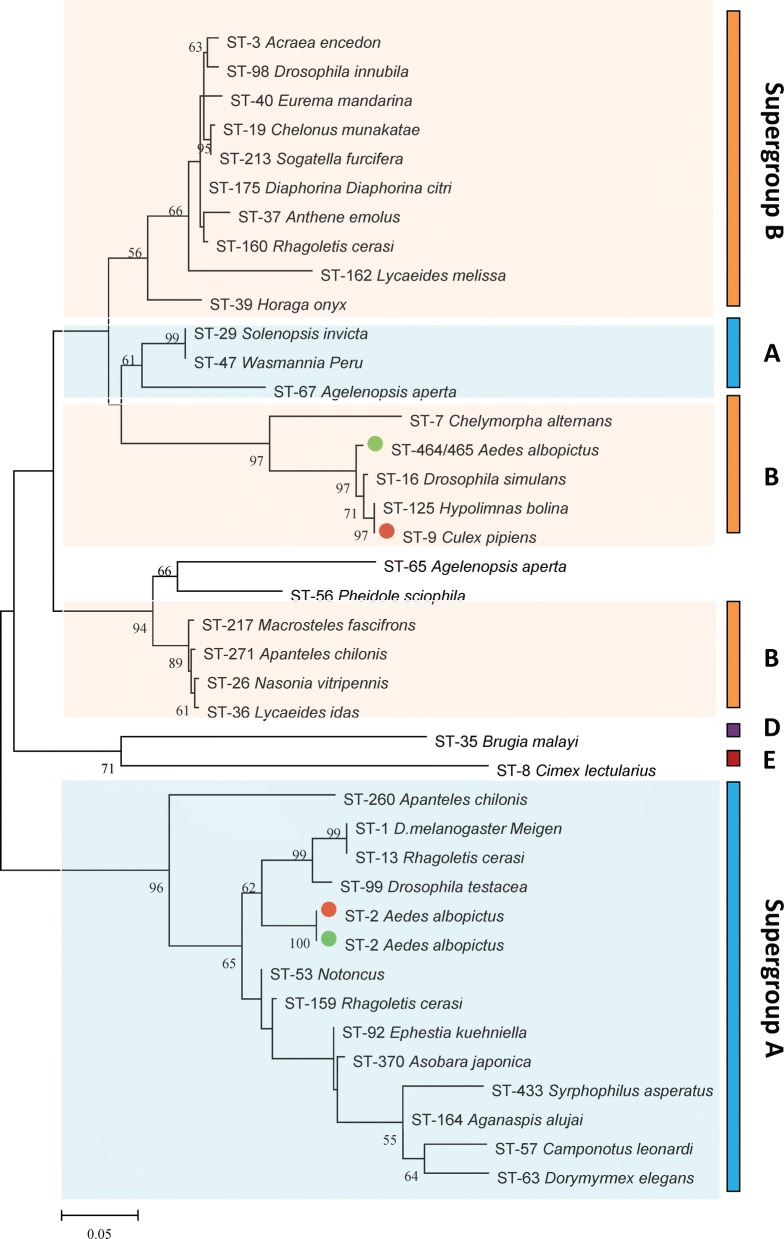

Sequence typing and phylogenetic analyses

For Wolbachia-specific wsp gene sequence analysis, several reported sequences with similarities of > 97% were obtained from GenBank for comparisons. The wsp sequence of Brugia malayi was selected as the outgroup. We also analyzed co-infection with different Wolbachia species. Furthermore, a reference list of Wolbachia isolates was constructed by searching the MLST database, which was selected for having a complete set of MLST and HVR profiles. A total of 40 of known STs were from supergroup A, supergroup B, supergroup D and supergroup F Wolbachia, and supergroup D (Table 3) and supergroup F Wolbachia were selected as outgroups. Allele sequences were downloaded from the MLST database and these Wolbachia sequences were manually edited with Chromas2.4 by DNAMAN and their translated amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE in MEGA6.0. Then, the concatenated data set of the five MLST genes was subjected to a phylogenetic analysis using MEGA 6.0. The wsp sequences were also subjected to a phylogenetic analysis using MEGA 6.0 using supergroup D and F Wolbachia strains as outgroups (for consistency with the MLST-based analysis). Maximum likelihood (ML) methods in MEGA 6.0 were used to analyze phylogenetic relationships. To select the optimal evolutionary model by critically evaluating the selected parameters, Find Best-Fit Substitution Model was conducted in MEGA 6.0 [26]. For the NCBI-wsp sequences, the concatenated dataset and the wsp sequences, the submodels T92 (Tamura 3-parameter), GTR+I+G and T92 (Tamura 3-parameter)+G were selected, respectively. The ML trees were constructed with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Table 3.

MLST allelic and WSP profiles of Wolbachia subjected for phylogenetic analyses

| ID | Supergroup | Host species | ST | gatB | coxA | hcpA | ftsZ | fbpA | wsp | HVR1 | HVR2 | HVR3 | HVR4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | Drosophila melanogaster | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 31 | 1 | 12 | 21 | 24 |

| 12 | A | Aedes albopictus | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 496 | A | Aedes bromeliae | 304 | 182 | 160 | 187 | 148 | 232 | |||||

| 114 | A | Notoncus sp. | 53 | 46 | 42 | 23 | 6 | 17 | 49 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| 120 | A | Camponotus leonardi | 57 | 49 | 44 | 53 | 42 | 49 | 52 | 41 | 42 | 45 | 42 |

| 167 | A | Agelenopsis aperta | 67 | 35 | 35 | 22 | 33 | 39 | 43 | 31 | 32 | 35 | 34 |

| 294 | A | Asobara japonica | 370 | 87 | 111 | 103 | 70 | 186 | 530 | 188 | 213 | 15 | 25 |

| 399 | A | Apanteles chilonis | 260 | 172 | 150 | 7 | 137 | 8 | 592 | 209 | 15 | 17 | 14 |

| 1682 | A | Syrphophilus asperatus | 433 | 234 | 84 | 257 | 200 | 120 | 689 | 11 | 9 | 267 | 302 |

| 56 | A | Rhagoletis cerasi | 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 12 | 21 | 11 |

| 2 | A | Solenopsis invicta | 29 | 19 | 20 | 22 | 17 | 20 | 28 | 21 | 21 | 25 | 21 |

| 61 | A | Rhagoletis cerasi | 159 | 53 | 84 | 85 | 70 | 79 | 113 | 67 | 77 | 12 | 9 |

| 68 | A | Agelenopsis aperta | 65 | 32 | 33 | 38 | 30 | 37 | 38 | 28 | 29 | 33 | 32 |

| 88 | A | Drosophila testacea | 99 | 10 | 72 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 1 | 11 | 21 | 11 |

| 107 | A | Wasmannia Peru | 47 | 43 | 20 | 46 | 38 | 46 | 28 | 21 | 21 | 25 | 21 |

| 96 | A | Aganaspis alujai | 164 | 54 | 52 | 62 | 82 | 62 | 75 | 11 | 9 | 15 | 25 |

| 129 | A | Dorymyrmex elegans | 63 | 19 | 21 | 55 | 46 | 53 | 51 | 42 | 43 | 47 | 25 |

| 325 | A | Ephestia kuehniella | 92 | 54 | 59 | 68 | 3 | 67 | 83 | 51 | 55 | 15 | 57 |

| 413 | A | Chelonus munakatae | 19 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 599 | 2 | 191 | 192 | 248 |

| 29 | B | Culex pipiens | 9 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 22 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| 499 | B | Mansonia africana | 305 | 9 | 38 | 189 | 36 | 4 | |||||

| 19 | B | Chelymorpha alternans | 7 | 9 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 14 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| 22 | B | Acraea encedon | 3 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 27 | B | Drosophila simulans | 16 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 13 |

| 34 | B | Nasonia vitripennis | 26 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 25 | 18 | 16 | 23 | 16 |

| 99 | B | Horaga onyx | 39 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 41 | 65 | 34 | 36 | 3 | 23 |

| 118 | B | Pheidole sciophila | 56 | 48 | 43 | 52 | 41 | 6 | 60 | 40 | 41 | 43 | 41 |

| 408 | B | Apanteles chilonis | 271 | 9 | 150 | 7 | 142 | 4 | 593 | 18 | 79 | 237 | 16 |

| 269 | B | Diaphorina Diaphorina citri | 175 | 109 | 86 | 88 | 126 | 27 | 160 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 23 |

| 39 | B | Lycaeides idas | 36 | 9 | 36 | 40 | 7 | 9 | 61 | 18 | 16 | 23 | 16 |

| 73 | B | Lycaeides melissa | 162 | 108 | 73 | 40 | 80 | 9 | 294 | 125 | 141 | 127 | 102 |

| 70 | B | Rhagoletis cerasi | 160 | 101 | 85 | 40 | 22 | 4 | 116 | 69 | 17 | 3 | 23 |

| 40 | B | Hypolimnas bolina | 125 | 4 | 14 | 40 | 73 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| 87 | B | Drosophila innubila | 98 | 79 | 71 | 88 | 69 | 27 | 82 | 2 | 35 | 98 | 23 |

| 97 | B | Anthene emolus | 37 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 63 | 19 | 17 | 24 | 33 |

| 200 | B | Eurema mandarina | 40 | 38 | 38 | 29 | 35 | 42 | 64 | 35 | 35 | 38 | 44 |

| 311 | B | Sogatella furcifera | 213 | 106 | 11 | 13 | 105 | 162 | 463 | 2 | 191 | 192 | 22 |

| 315 | B | Macrosteles fascifrons | 217 | 135 | 120 | 141 | 108 | 197 | 536 | 191 | 220 | 23 | 16 |

| 37 | D | Brugia malayi | 35 | 28 | 29 | 33 | 26 | 30 | 34 | 24 | 24 | 27 | 26 |

| 36 | F | Cimex lectularius | 8 | 26 | 27 | 31 | 24 | 28 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

wAlbA and wAlbB Wolbachia strain quantitation

Twenty-eight mosquitoes from regions with local dengue cases (Guangzhou and Jinghong), with only imported cases (Xiamen and Haikou) and without dengue cases (Wenchang and Fuzhou) were amplified individually by quantitative PCR using strain-specific primers qAF/qAR [27] and qBF/qBR (Table 2) to examine the relationship between Wolbachia density in field-collected Ae. albopictus and the presence of dengue virus. The Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Hercules, USA) and GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega) were used in our study. PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 µl containing 10 µl of GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix, 0.5 µM of each primer, 2 µl of template DNA and 7 µl of RNase-free water. Reactions were mixed with an electronic pipette. The thermal cycling conditions were: 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 50 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, primer Tm (wAlbA 55 °C, wAlbB 58 °C and RPS6 55 °C) for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and finally 72 °C (read temperature) for 15 s. The melting curve was constructed between 49 °C and 63 °C. We used a serial dilution of pEASY®-T5 Zero Cloning vectors containing one copy each of RPS6 [28], wAlbAq-wsp and wAlbBq-wsp gene fragments, and used their primers set up in each PCR to plot standard curves, in case any binding efficiency difference appeared. Every mosquito DNA template was quantified three times for each of the RPS6, wAlbAq-wsp and wAlbBq-wsp genes. Assuming that each gene was present in a single copy per haploid genome, the ratio between wsp and RPS6 provided the number of Wolbachia genomes relative to the number of Aedes genomes [29].

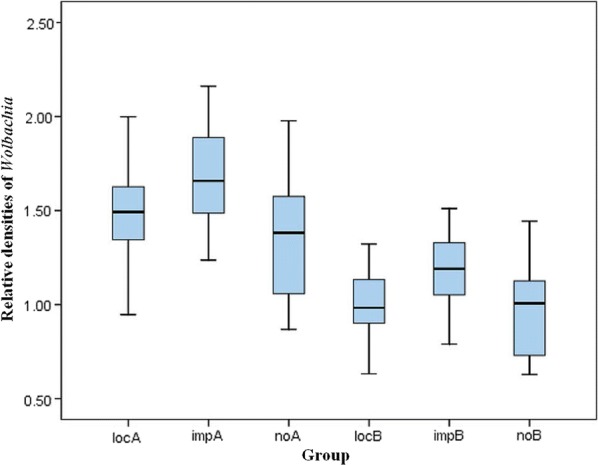

Statistical analysis

To compare the densities of the two Wolbachia strains in field mosquitoes in five regions (with different adult sizes), data were normalized to the expression of the host rps6 gene. Analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics (17.0). Chi-square tests were performed to compare the prevalence of Wolbachia infections and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare densities of Wolbachia from different regions for normally distributed data using SPSS Statistics (17.0). Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. For better presentation of results, locA and locB were used to denote the densities of supergroup A and supergroup B, respectively, from regions with local dengue cases; impA and impB were used to denote the densities of supergroup A and supergroup B, respectively, from regions with only imported dengue cases; and noA and noB were used to denote the densities of supergroup A and supergroup B, respectively, from regions with no dengue cases.

Results

Prevalence of Wolbachia infections

A total of 693 adult Ae. albopictus were obtained from five different climatic regions in China and were examined for Wolbachia infection status. Of these, 93.36% (647/693) were PCR-positive for Wolbachia using wsp and 16S rDNA primers [30]. The quality of extracted DNA was good, and the samples were all identified as Ae. albopictus [31]. Specific primers for wAlbA and wAlbB, derived from the rapidly evolving wsp outer-surface protein gene of Wolbachia, were used to screen for these bacteria in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. The PCR results showed that 83.26% (577/693) of the mosquitoes sampled were infected with supergroup A and 91.05% (631/693) were infected with supergroup B Wolbachia strains. The prevalence of co-infection was 80.95% (561/693). Individuals singly infected with supergroup A and supergroup B Wolbachia represented 2.31% (16/693) and 10.10% (70/693) of all mosquitoes, respectively. We also found 46 uninfected individuals (Table 4).

Table 4.

Infection status of Wolbachia based on PCR results of field-collected Ae. albopictus adults

| Climate region | Total | No. of infected (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single A | Single B | A and B | W+ | ||

| Edge of tropical | 186 | 11 (5.91) | 26 (13.98) | 135 (72.58) | 172 (92.47) |

| South subtropical | 143 | 1 (0.70) | 15 (10.49) | 117 (81.82) | 133 (93.01) |

| Mid-subtropical | 109 | 1 (0.92) | 13 (11.93) | 80 (73.39) | 94 (86.24) |

| North subtropical | 102 | 2 (1.96) | 12 (11.76) | 85 (83.33) | 99 (97.06) |

| Warm temperate zone | 153 | 1 (0.65) | 4 (2.61) | 144 (94.12) | 149 (97.39) |

| Total | 693 | 16 (2.31) | 70 (10.10) | 561 (80.95) | 647 (93.36) |

Note: W+ represents the positive rate of Wolbachia in Ae. albopictus

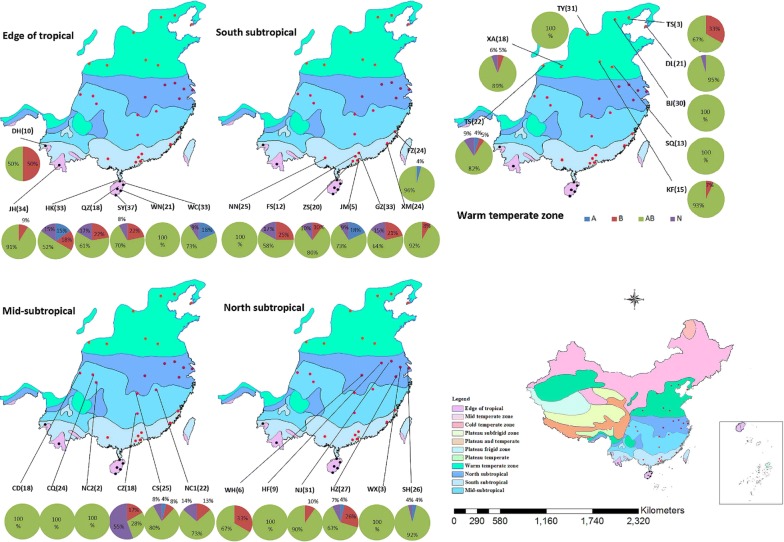

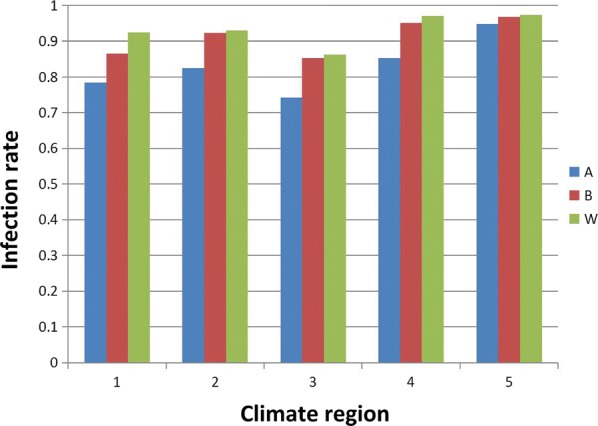

The natural prevalence of Wolbachia infection in 34 different locations of the five climatic regions is presented in Fig. 1. Chi-square tests of Wolbachia prevalence among the five different climate regions (Fig. 2) revealed a significant difference (χ2 = 15.438, df = 4, P = 0.004). Similarly, the prevalence of supergroup A and B Wolbachia differed significantly among the five climate regions (χ2 = 24.199, df = 4, P < 0.0001 and χ2 = 17.390, df = 4, P = 0.0020, respectively). Further analysis showed that the prevalence of Wolbachia infection was significantly different in four regions: Edge of tropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 4.029, df = 1, P = 0.045); Mid-subtropical vs North subtropical (χ2 = 7.906, df = 1, P = 0.005); and Mid-subtropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 11.759, df = 1, P = 0.001). However, the prevalence of Wolbachia infection in the South subtropical region did not show any significant differences compared with any of the other four regions. For the prevalence of supergroup A Wolbachia, significant differences were detected for five regions: Edge of tropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 18.298, df = 1, P < 0.0001); South subtropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 11.204, df = 1, P = 0.001); Mid-subtropical vs North subtropical (χ2 = 3.917, df = 1, P = 0.048); Mid-subtropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 22.480, df = 1, P < 0.0001); and North subtropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 6.698, df = 1, P = 0.010). For supergroup B Wolbachia, significant differences were observed in four regions: Edge of tropical vs North subtropical (χ2 = 5.147, df = 1, P = 0.023); Edge of tropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 10.770, df = 1, P = 0.001); Mid-subtropical vs North subtropical (χ2 = 5.620, df = 1, P = 0.018); and Mid-subtropical vs Warm temperate zone (χ2 = 11.242, df = 1, P = 0.001). Similar to the overall prevalence of Wolbachia infections, the south subtropical region did not show any substantial difference compared with any of the other four regions (Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 2.

Infection rates for different sites in the Edge of tropical, South subtropical, Mid-subtropical, North subtropical and Warm temperate zones. Black, red, pink, purple and brown dots are the sample sites at the edge of Tropical, South subtropical, Mid-subtropical, North subtropical and Warm temperate zones, respectively. Blue square A, rate of single-infected with wAlbA mosquitoes; brown square B, rate of single-infected with wAlbB mosquitoes; green square AB, rate of co-infected with wAlbA and wAlbB mosquitoes; purple square N, rate of Wolbachia-negative mosquitoes

Fig. 3.

Wolbachia infection rates in Ae. albopictus of the five climate regions in China: 1, Edge of tropical; 2, South subtropical; 3, Mid-subtropical; 4, North subtropical; 5, Warm temperate zone. Blue bars (A), wAlbA infection rate in Ae. albopictus; brown bars (B), wAlbB infection rate in Ae. albopictus; green bars (W), rate of co-infection with wAlbA and wAlbB in Ae. albopictus

Nucleotide sequence analysis of Wolbachia from Ae. albopictus

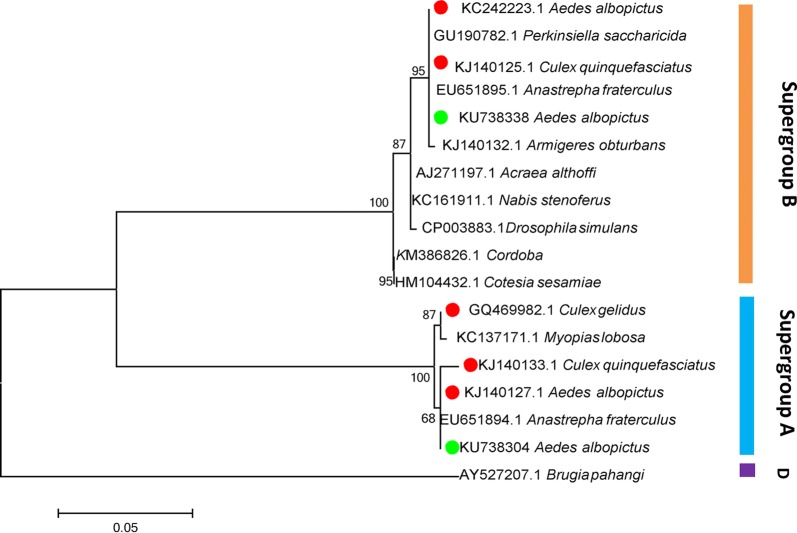

DNA sequencing analysis indicated that Ae. albopictus from different locations in China harbored two different Wolbachia strains: wAlbA and wAlbB (Fig. 4). The WSP profiles of wAlbA and wAlbB for wsp, HVR1, HVR2, HVR3 and HVR4 were 1, 1, 1, 1 and 1, and 169, 10, 82, 10 and 84, respectively, suggesting that these two Wolbachia strains were very stable.

Fig. 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on wsp gene sequences for Wolbachia from different hosts from GenBank. Red dots indicate reported Wolbachia strains of mosquitoes; green dots indicate Wolbachia strains of Ae. albopictus sampled in the present study

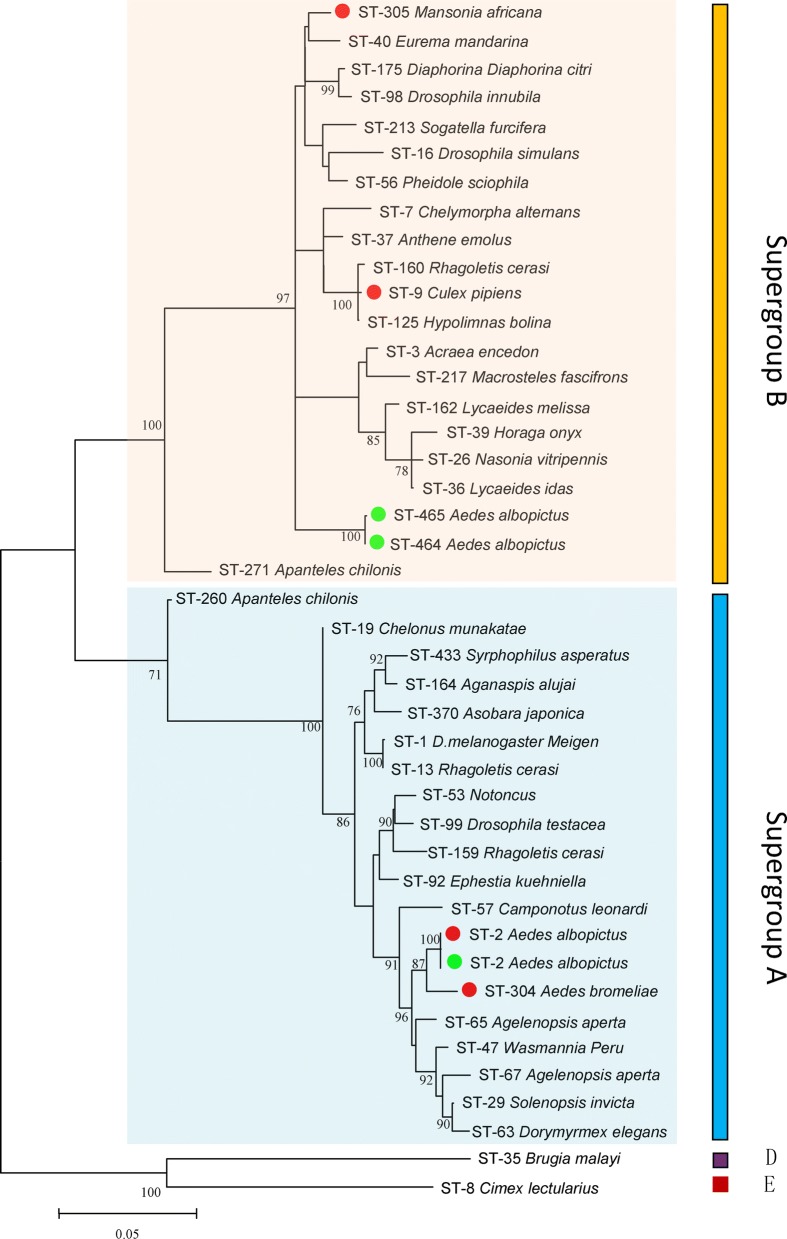

Phylogenetic analysis based on the concatenated sequences of all MLST loci showed that ST-2 was wAlbA, but no closely-related STs were identified for wAlbB. We submitted our sequences to the MLST database, and received new ST codes (ST-464, ST-465, designated for wAlbB1, wAlbB2 respectively). wAlbB1 and wAlbB2 only differed by a single base pair: gatB16A and gatB16G, respectively. The five MLST genes of wAlbA shared the same alleles as ST-2, as previously demonstrated [19]; however, three of the five MLST genes (fbpA, gatB and hcpA) of wAlbB1 and two of the five genes (fbpA and hcpA) of wAlbB2 shared alleles with other STs. In total, 40 known Wolbachia STs in the MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/Wolbachia/) were used as a dataset to infer the phylogeny of Wolbachia infecting field-collected Ae. albopictus. The MLST-based ML tree (Fig. 5) separated the isolates into three major clusters: supergroup A, supergroup B, and supergroup D + supergroup F. For the wsp-based ML tree, the isolates were separated into supergroup A, supergroup D, supergroup F and a mixture of supergroup A and supergroup B branches. According to these data, it was safe to classify ST-464 and ST-465 as strains of supergroup B. In the wsp-based ML tree (Fig. 6), wAlbA and wAlbB formed a cluster with strains from other mosquito species (Culex quinquefasciatus and Culex gelidus). Similarly, in the MLST-based tree, wAlbA (ST-2) formed a clade with ST-304 whose host is Aedes bromeliae. In supergroup B, wAlbB (ST-464 and ST-465) did not form a clade with ST-305 and ST-9, whose hosts were Mansonia africana and Culex pipiens, respectively (Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 5.

MLST-based maximum likelihood tree for Wolbachia from different hosts. Red dots indicate reported Wolbachia strains of mosquitoes; green dots indicate Wolbachia strains of Ae. albopictus sampled in the present study

Fig. 6.

wsp-based maximum likelihood tree for Wolbachia from different hosts. Red dots indicate reported Wolbachia strains of mosquitoes; green dots indicate Wolbachia strains of Ae. albopictus sampled in the present study

wAlbA and wAlbB Wolbachia strain quantitation

The relative densities of the wAlbA and wAlbB strains were estimated for individual females sampled from regions with local dengue cases, with only imported dengue cases, and without dengue cases. The data were normalized using the host rps6 gene, which also allowed the densities of the two Wolbachia strains to be compared between different adult sizes.

Figure 7 shows a higher density of the wAlbB strain relative to wAlbA, and this difference was significant in three different regions: locA vs locB (ANOVA, F(1, 54) = 67.143, P < 0.0001), impA vs impB (ANOVA, F(1, 54) = 38.955, P < 0.0001), and noA vs noB (ANOVA, F(1,54) = 12.650, P = 0.001). Moreover, both wAlbA and wAlbB strains showed significantly lower densities in regions with only imported dengue cases than in the other two regions [wAlbA (ANOVA, F(2, 81) = 10.203, P < 0.0001) and wAlbB (ANOVA, F(2, 81) = 7.468, P = 0.001)]. Neither locA vs impA, locA vs noA, locB vs impB, nor locB vs noB showed any significant difference, which may indicate a relationship between the fluctuation of Wolbachia density in field Ae. albopictus and the invasion of dengue virus.

Fig. 7.

Relative Wolbachia densities in Ae. albopictus collected in different regions in China. Abbreviations: loc-A, relative densities of wAlbA in the regions with local dengue cases; imp-A, relative densities of wAlbA in the regions with import dengue cases; no-A, relative densities of wAlbA in the regions without dengue cases; loc-B, relative densities of wAlbB in the regions with local dengue cases; imp-B, relative densities of wAlbB in the regions with import dengue cases; no-B, relative densities of wAlbB in the regions without dengue cases

Discussion

Wolbachia is a bacterial endosymbiont that infects the reproductive tissues of arthropods, mainly insects. It is spread primarily via the ova cytoplasm and alters the reproductive success of its host, thus making it a suspected driver of development and speciation. The prevalence of Wolbachia in insects has been reported as ranging from 20% to 65% [32]. Our results showed a prevalence of 93.36% for Wolbachia in natural populations of Ae. albopictus in China, slightly lower than the 100% previously reported in Guangzhou (China), Orissa (India), Chachoengsao (Thailand) [18, 33, 35] and over 99% in Korea [34]. Furthermore, single infections with both wAlbA and wAlbB were detected in our study and the prevalence of wAlbB (10.10%) strains was higher than that of wAlbA strains (2.31%). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of single wAlbB infections in field-collected Ae. albopictus in Changsha, Chenzhou and Wuhan, China, and our findings were similar to those reported in Guangzhou [18]. These results thus support and validate the work of O’Neill et al. [35]. In the present study, 28S rRNA was used to assess the quality of DNA extraction [30] and the cox1 gene of Ae. albopictus was sequenced to rule out samples that were not Ae. albopictus. In addition, to obtain an accurate estimate of the prevalence of wAlbA and wAlbB, qPCR was used to check negative samples and indicated an increased prevalence of 83.26% and 91.05% for supergroup A and B Wolbachia strains, respectively.

Wolbachia significantly and efficiently reduced the proportions of mosquitoes achieving infection and transmission potential across the different regions. Wolbachia density is sensitive to temperature variations [36]. A Chi-square test of Wolbachia prevalence among the five different climate regions in China revealed that geographical location and climate may have a significant effect on the prevalence of Wolbachia in natural populations of Ae. albopictus. As shown in Fig. 3, for both wAlbA and wAlbB, the prevalence of Wolbachia infection in the Mid-subtropical region was lower than in other climate regions; the difference between the North subtropical region and the Warm temperate zone was apparent in all three measures of prevalence. There was a clearly lower prevalence in Chenzhou (Fig. 2), which may be the reason why rates in the Mid-subtropical region were lower than in other regions. Aside from this, the rates of Wolbachia infection did not show any linear relationships, which may imply that there is no absolute correlation between climate region and Wolbachia infection.

MLST is an important source of sequence data for comparative genetics, providing a tool for exploring molecular evolutionary methods in intracellular bacteria [19]. Our results show that in both the MLST-based and wsp-based ML trees, Wolbachia isolates included in the analyses are placed in supergroups A and B (Fig. 5). However, in the wsp-based ML tree (Fig. 6), a mixed cluster of supergroups A and B was identified, with ST-19, ST29, ST47, ST65 and ST67 belonging to a supergroup associated with isolates from supergroup B. This suggests that MLST-based genotyping is perhaps more accurate than the wsp-based method. Our results may, however, be explained by the fact that the sharing of wsp sequences between A and B strain supergroups indicates a strong genetic cohesiveness of Wolbachia strains [37]. Moreover, for supergroup B in the wsp-based ML tree, Wolbachia of Ae. albopictus did not show an exact match with previously identified STs. Furthermore, we identified the new ST-464 strain wAblB1 and the new ST-465 strain wAblB2. ST-464 was found in all locations, but ST-465 strains were only found in single infected mosquitoes from Changsha and Chenzhou and co-infected mosquitoes from Wuhan and Nanchang. This may reflect the various states of Wolbachia infection in these locations.

The density of the endosymbiont Wolbachia plays an important role in crossing sterility, which is known as a cytoplasmic incompatibility and limits the degree of parental spread. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes can be superinfected with the Wolbachia strains wAlbA and wAlbB [38]. In our study, the wAlbB strain was found at a higher density than wAlbA in Ae. albopictus, which is consistent with the results of two previous studies [38, 39]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess relative Wolbachia densities in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes from different natural populations, which were sampled from regions with different dengue fever load. The relative density of Wolbachia (wAlbA and wAlbB) in mosquitoes from regions with only imported dengue cases was lower than that in mosquitoes from regions with local dengue cases and without dengue cases. The decrease of Wolbachia density could lead to the loss of protection by the host immune system [40]. We hypothesize that the imported dengue cases caused a lowering of Wolbachia densities in natural mosquito populations and that densities of virus in these mosquitoes will increase. Sometime later, densities of virus and Wolbachia would come to a balance in the natural mosquito populations and thereafter could transmit virus smoothly, resulting in local dengue case emerging. This hypothesis has yet to be substantiated by other reports, but our results may reflect the alarm reaction of natural mosquito populations in response to invasion of dengue virus, which is embodied in the fluctuation of Wolbachia densities. Furthermore, the low prevalence in Chenzhou, which also has imported dengue cases, may be explained if our hypothesis were correct [41, 42]. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between Wolbachia densities in natural Ae. albopictus mosquitoes and the invasion of dengue virus.

In this study, we obtained adult mosquitoes at a variety of ages from different parts of China. Because adults had only recently emerged (1 or 2 days), these may have had Wolbachia densities that were too low to be detected. Our subsequent studies will be based on field-collected larvae, which will be brought back to the laboratory and used for further research after emergence.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the natural prevalence of Wolbachia infections in China was much lower than the prevalence in other countries or regions. The prevalence of Wolbachia was significantly different among five different climatic regions. The phylogenetic relationships of Wolbachia in field-collected Ae. albopictus were estimated based on MLST and wsp analyses, and showed that these strains were rather stable. However, wAlbB (464/465) and Wolbachia strains did not form a clade with Wolbachia strains from other mosquitoes. Moreover, the lower densities of Wolbachia in regions with only imported dengue cases suggested a relationship between the fluctuation of Wolbachia density in natural Ae. albopictus populations and the invasion of dengue virus.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MLST

multilocus sequence typing

- ST

sequence type

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ddH2O

double distilled water

- WSP

Wolbachia surface protein gene

- HVR

hypoxic ventilatory response

Authors’ contributions

YH, QL, BC, ZX and XL planned the project and wrote the paper. QL, BC, YG, DR, JW and XW conducted the field survey. YH carried out the multiplex PCR assay. XL and HW contributed to data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 81273139) and National Major Research and Development Programme (Grant No. 2016YFC1200802).

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. Representative nucleotide sequences generated in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KU738304-KU738385 and KU738386-KU738431. The sequences of gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ, fbpA and wsp were deposited in the MLST database and the allele numbers are 247/242, 229, 166, 210, 27 respectively.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yaping Hu and Zhiyong Xi contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Yaping Hu, Email: huyap9009@163.com.

Zhiyong Xi, Email: xizhiyong@yahoo.com.

Xiaobo Liu, Email: liuxiaobo@icdc.cn.

Jun Wang, Email: wangjun@icdc.cn.

Yuhong Guo, Email: guoyuhong@icdc.cn.

Dongsheng Ren, Email: rendongsheng@icdc.cn.

Haixia Wu, Email: wuhaixia@icdc.cn.

Xiaohua Wang, Email: 1425039903@qq.com.

Bin Chen, Email: c_bin@hotmail.com.

Qiyong Liu, Email: liuqiyong@icdc.cn.

References

- 1.Tennakone K, De Silva LA. Host-vector interaction in dengue: a simple mathematical model. Ceylon Med J. 2018;63:58–64. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v63i2.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iturbe-Ormaetxev I, Walker T, OʼNeill SL. Wolbachia and the biological control of mosquito-borne disease. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:508–518. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker T, Johnson P, Moreira L, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu F, McMeniman C, et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476:450–453. doi: 10.1038/nature10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zug R, Hammerstein P. Still a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci I, Cancrini G, Gabrielli S, Dʼamelio S, Favia G. Searching for Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae): large polymerase chain reaction survey and new identifications. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:562–567. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werren JH. Biology of Wolbachia. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997;42:587–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JA, Hurst GD. Wolbachia pipientis: microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:71–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:741–751. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rances E, Ye YH, Woolfit M, McGraw EA, O’Neill SL. The relative importance of innate immune priming in Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002548. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y, Wang JL, Liu C, Wang CP, Walker T, Wang YF. Differentially expressed profiles in the larval testes of Wolbachia infected and uninfected Drosophila. BMC Genom. 2011;12:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science. 2008;322:702. doi: 10.1126/science.1162418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1000002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann A, Montgomery B, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson P, Muzzi F, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476:454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen LH, Wilson ME. Dengue and chikungunya in travelers: recent updates. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:523–529. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328356ffd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frentiu FD, Zakir T, Walker T, Popovici J, Pyke AT, Vanden HA, et al. Limited dengue virus replication in field-collected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen TH, LeNguyen H, Nguyen TY, Vu SN, Tran ND, Le TN, et al. Field evaluation of the establishment potential of wmelpop Wolbachia in Australia and Vietnam for dengue control. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:563. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutra HLC, dosSantos LMB, Caragata EP, Silva JBL, Villela DAM, Maciel-de-Freitas R, et al. From lab to field: the influence of urban landscapes on the invasive potential of Wolbachia in Brazilian Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang D, Zhan X, Wu X, Yang X, Liang G, Zheng Z, et al. A field survey for Wolbachia and phage WO infections of Aedes albopictus in Guangzhou City, China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:399–404. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldo L, Dunning HJC, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7098–7110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bian G, Joshi D, Dong Y, et al. Wolbachia invades Anopheles stephensi populations and induces refractoriness to plasmodium infection. Science. 2013;340(6133):748–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1236192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xi Z. Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science. 2005;310(5746):326–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1117607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan W, Qiyong L, Jinfeng W. A study on the potential distribution of Aedes albopictus and risk forecasting for future epidemics. Beijing: China CDC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baolin L, Feng L, et al. Fauna of China. Beijing: Beijing Science Press; 1997. VIII. Diptera: mosquitoes. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braig HR, Zhou W, Dobson SL, O’Neill SL. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2373–2378. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.9.2373-2378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou W, Rousset F, OʼNeill S. Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc Biol Sci. 1998;265:509–515. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tortosa P, Courtiol A, Moutailler S, Failloux AB, Weill M. Chikungunya-Wolbachia interplay in Aedes albopictus. Insect Mol Biol. 2008;17:677–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina CA, Gupta L, Richardson J, Bennett K, Black W, Barillas-Mury C. Effect of mosquito midgut trypsin activity on dengue-2 virus infection and dissemination in Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:631–637. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zele F, Nicot A, Berthomieu A, Weill M, Duron O, Rivero A. Wolbachia increases susceptibility to Plasmodium infection in a natural system. Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281:20132837. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi Y, Jing W, YunLi T, Dong G, Dong C. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of Wolbachia in different geographical populations of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Acta Entomol Sin. 2013;56:323–328. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Y, Shen ZR, Wang Z, Li ZY. Distribution and genetic stability of Wolbachia in populations of Trichogramma chilonis. J Environ Entomol. 2010;32:188–193. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maren W, Sara S. Investigating the frequency of Wolbachia infection in West Virginia arthropods. Proc WVAS. 2017;89:1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das B, Satapathy T, Kar SK, Hazra RK. Genetic structure and Wolbachia genotyping in naturally occurring populations of Aedes albopictus across contiguous landscapes of Orissa, India. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park CH, Lim H, Kim H, Lee WG, Roh JY, Park MY, et al. High prevalence of Wolbachia infection in Korean populations of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) J Asia Pac Entomol. 2015;19:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2015.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitrayapong P, Baimai V, O’Neill SL. Field prevalence of Wolbachia in the mosquito vector Aedes albopictus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:108–111. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye YH, Carrasco AM, Dong Y, Sgro CM, McGraw EA. The effect of temperature on Wolbachia-mediated dengue virus blocking in Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:812–819. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldo L, Werren JH. Revisiting Wolbachia supergroup typing based on WSP: spurious lineages and discordance with MLST. Curr Microbiol. 2007;55:81–87. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-0055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dutton TJ, Sinkins SP. Strain-specific quantification of Wolbachia density in Aedes albopictus and effects of larval rearing conditions. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinkins S, Braig H, Oneill S. Wolbachia pipientis: bacterial density and unidirectional cytoplasmic incompatibility between infected populations of Aedes albopictus. Exp Parasitol. 1995;81:284–291. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osborne SE, Iturbe OI, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN. Antiviral protection and the importance of Wolbachia density and tissue tropism in Drosophila simulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:6922–6929. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01727-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mousson L, Zouache K, Arias GC, Raquin V, Mavingui P, Failloux AB. The native Wolbachia symbionts limit transmission of dengue virus in Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bian G, Zhou G, Lu P, Xi Z. Replacing a native Wolbachia with a novel strain results in an increase in endosymbiont load and resistance to dengue virus in a mosquito vector. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. Representative nucleotide sequences generated in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KU738304-KU738385 and KU738386-KU738431. The sequences of gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ, fbpA and wsp were deposited in the MLST database and the allele numbers are 247/242, 229, 166, 210, 27 respectively.