Abstract

Background:

Adolescents who live near more alcohol outlets tend to consume more alcohol, despite laws prohibiting alcohol purchases for people aged < 21 years. We examined relationships between adolescents’ exposure to alcohol outlets, the sources through which they access alcohol, and their alcohol consumption.

Methods:

Participants for this longitudinal study (n=168) were aged 15–18 years and were from 10 cities in the San Francisco Bay Area. We collected survey data to measure participant characteristics, followed by 1 month of GPS tracking to measure exposure to alcohol outlets (separated into exposures near home and away from home for bars, restaurants, and off-premise outlets). A follow-up survey approximately 1 year later measured alcohol access (through outlets, family members, peers aged < 21 years, peers aged ≥ 21 years) and alcohol consumption (e.g. count of drinking days in last 30). Generalized structural equation models related exposure to alcohol outlets, alcohol access, and alcohol consumption.

Results:

Exposure to bars and off-premise outlets near home was positively associated with accessing alcohol from peers aged < 21, and in turn, accessing alcohol from peers aged < 21 was positively associated with alcohol consumption. There was no direct association between exposure to alcohol outlets near home or away from home and alcohol consumption.

Conclusions:

Interventions that reduce adolescents’ access through peers aged < 21 may reduce adolescents’ alcohol consumption.

Keywords: Access, Adolescent, Alcohol, Neighborhood, Outlet, Structural Equation Model, Teen

1. Introduction

Two clear and incongruous observations motivate this paper. First, alcohol consumption is common among US adolescents. The 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates that 7.4 million (20%) adolescents aged 12 to 20 consumed alcohol within the previous 30 days, and 4.5 million (12%) binged on 4 or more drinks for females and 5 or more drinks for males (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). The high prevalence of this risk behavior persists despite a trend of decreasing consumption over the last quarter century (Esser et al., 2017). Second, alcohol consumption is illegal for US adolescents. Laws in all 50 States and the District of Columbia restrict purchases in retail outlets to persons aged ≥ 21 who have a valid identification (Babor et al., 2010). Given that alcohol use by adolescents is both common and illegal, a logical line of inquiry is to examine the sources through which adolescents access alcohol, with a view to identifying possible preventive interventions to reduce alcohol consumption. These are critical public health questions because approximately 4,300 adolescents die due to alcohol-related causes (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2016) and 190,000 attend emergency rooms each year (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012).

Descriptive studies largely agree about the sources through which adolescents access alcohol. The 2018 Monitoring the Future study documented that 86% of 12th graders considered alcohol “fairly easy” or “very easy” to get (Johnston et al., 2019). Other studies document that those who actually access alcohol most commonly nominate peers as their primary sources (Gilligan et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 1998; Wagenaar et al., 1996), and a smaller proportion indicate that they access alcohol from home with their parents’ permission (Gilligan et al., 2012; Hearst et al., 2007; Ward and Snow, 2011). Fewer still report accessing alcohol through retail sources (Harrison et al., 2000; Wagenaar et al., 1996), despite research finding that a considerable proportion of retail outlets are willing to sell to minors (Britt et al., 2006; Forster et al., 1994; Forster et al., 1995; Gosselt et al., 2012; Lynne-Landsman, 2016; Paschall et al., 2007; Preusser and Williams, 1992; Toomey et al., 2008). Importantly, access through peer, home, and retail sources differs according to adolescents’ demographic characteristics (Harrison et al., 2000; Hearst et al., 2007; Wagenaar et al., 1996). For example, younger adolescents are more likely than older adolescents to access alcohol through their parents (Hearst et al., 2007), females are more likely than males to access alcohol through peers, and racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than whites to buy alcohol at retail outlets (Harrison et al., 2000).

The sources through which adolescents’ access alcohol is related to their patterns of alcohol consumption. Dent and colleagues (2005) surveyed 11th grade students in Oregon and found individuals who accessed alcohol through peers aged under 21 reported more frequent alcohol consumption, binging, drunk driving, and riding in a vehicle with a drunk driver. Other studies find similar links between alcohol consumption and alcohol access through the home (Deutsch et al., 2017; Tobler et al., 2009) and through retail outlets such as bars (Casswell and Zhang, 1997). Possessing a fake ID is associated with increased alcohol consumption and related harms (Morleo et al., 2010), although it is not clear if this association is causal or if possessing a fake ID marks for other characteristics, such as risk taking (Stogner et al., 2016). Event-level studies find that perceived ease of access (Bersamin et al., 2016) and accessing alcohol through adults in the previous year are associated with increased alcohol intake, but drinking with a parent present is associated with lower single-session intake (Foley et al., 2004).

A complementary group of studies identifies that certain neighborhood conditions predict the sources through which adolescents access alcohol. Most notably, the concentration of retail alcohol outlets near adolescents’ homes seems to affect alcohol access (Reboussin et al., 2011). For example, Chen et al (2009) found that adolescents who live in ZIP codes with more alcohol outlets were more likely to access alcohol through home, through peers aged under 21, and though retail outlets (either directly or by asking a stranger), but not through peers aged 21 or older. Similarly, Treno et al (2008) found that greater concentrations of off-premise outlets around the home were associated with greater perceived ease of access and more frequent direct purchases through retail sources, but less frequent access through peers and other social sources. Importantly, retail outlets are more likely to sell alcohol to adolescents when there are more outlets nearby (Chen et al., 2009; Freisthler et al., 2003), possibly due to increased competition (Gruenewald, 2007).

In addition to predicting the sources through which adolescents access alcohol, neighborhood conditions are also directly related to the quantity and frequency of adolescents’ alcohol consumption. Specifically, adolescents who live in cities (Treno et al., 2003) and neighborhoods (Kypri et al., 2008; Reboussin et al., 2011; Scribner et al., 2008; Truong and Sturm, 2009) with more alcohol outlets consume more alcohol, and these associations are typically strongest for on-premise outlets (Sherk et al., 2018) near adolescents’ homes (Morrison et al., 2019). For example, in generalized structural equation models, Rowland et al. (2016) identified that exposure to alcohol outlets predicted increased alcohol consumption one year later among Australian adolescents. A possible explanation for these findings is that frequent exposure to alcohol outlets affects adolescents’ perceptions of normative behavior regarding alcohol consumption (Tobler et al., 2011). Alternatively, alcohol outlets tend to be located in disorganized neighborhoods (Gorman and Speer, 1997; Morrison et al., 2015; Theall et al., 2009), and the absence of social controls may contribute to deviant behavior, including greater alcohol consumption (Shaw and McKay, 1942).

Thus, previous studies identify that (i) the sources through which adolescents access alcohol is related to their alcohol consumption, (ii) neighborhood conditions, including alcohol outlet density, affect the sources through which adolescents access alcohol, and (iii) neighborhood conditions are associated with adolescents’ alcohol consumption. The aim of this study is to combine these perspectives and elucidate the paths through which neighborhood conditions, alcohol access, and alcohol consumption are interrelated for adolescents. We interpret our results in the context that alcohol access and consumption by adolescents is both common and illegal, and that harms related to alcohol consumption are an important public health problem.

2. Method

2.1. Study Setting

Healthy Communities for Teens is a cohort study of exposure to physical and social environmental conditions and risks for alcohol, tobacco and other drug use and problem behaviors among adolescents. Study participants were a convenience sample of 261 adolescents recruited from 10 cities in the San Francisco Bay Area. The cities were the closest to the Prevention Research Center (Berkeley, CA) from among a random sample of 50 California cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000. The Prevention Research Center has studied the social ecology of alcohol use and related harms in these 50 cities over several years (Gruenewald et al., 2014). Healthy Communities for Teens participants were recruited using a combination of online advertisements, paid peer referrals, posted flyers, phone recruitment, and outreach at community venues. Eligible teens (i) resided in one of the 10 study cities, (ii) were aged 14 to 16 years between July 2015 and August 2016, (iii) had an active email address, and (iv) spoke English or Spanish. Of the 261 participants recruited at baseline, we retained and had complete data for 168 participants through three annual waves (retention rate = 64.4%). This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (Berkeley, CA).

2.2. Data Collection

We sent each participant a weblink to an annual survey approximately twelve months apart during each study year for three annual waves. After they completed each annual survey, a field research assistant met the participant in person to provide them with a GPS-enabled Apple iPhone 5c which they carried for one month. During this time we recorded participants’ point locations (latitude, longitude) and a date and time stamp every 60 seconds using ActSoft’s Comet Smart Tracker (ActSoft Inc., Tampa, FL). Wave 2 data collection was conducted from July 2016 to August 2017, and Wave 3 data collection was conducted from July 2017 to August 2018.

2.3. Measures

The main outcomes were measures of alcohol consumption taken from the Wave 3 annual survey. Wave 3 alcohol consumption provided the outcome because alcohol consumption increased as participants aged and the Wave 3 observations provided the greatest variance. Participants were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink alcohol?” (frequency); “How many drinks did you usually have each time on a typical occasion?” (quantity); “On how many days have you gotten drunk or ‘very high’ on alcohol” (drunk); and, “On how many days did you drink four or more drinks in the same setting?” (binge).

The exposures of interest were measures of proximity to alcohol outlets. These measures were taken from the Wave 2 GPS data in order to ensure that the exposure preceded the outcome, and separated outlets encountered near home from those encountered away from the home. First, we measured exposure to alcohol outlets near home as counts of alcohol outlets within the Census block group in which participants lived during Wave 2. Second, we calculated exposure to alcohol outlets away from home using the GPS data (Morrison et al., 2019). Sequential GPS points were connected by the shortest distance on a Euclidean plane to produce a “polyline” for each participant composed of 12,069 to 43,071 segments. Each polyline segment included the date and time for the start- and end-points, and the combination of all polyline segments for a participant represented their four-week activity path. We deleted points that were within 100m of home. Taking distance buffers of 50m, 100m, and 200m around the polyline segments, the total number of outlets within the polyline buffers were weighted by the duration of each corresponding polyline, then divided by the total time each participant was tracked, thereby calculating the average “outlet-hours” per hour of exposure participants accumulated away from home along their activity paths. These buffer distances are approximately similar to the distance within a street, along a street, and across a block. All measures of exposure to alcohol outlets were calculated using geocoded 2013 data from the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control. We categorized outlets by license type as bars (license type 23, 40, 42, 48, 61, and 75), restaurants (41 and 47), and off-premise outlets (20 and 21).

Potential confounders were participants’ sex (male vs. female), age in years at the time of the Wave 2 annual survey (continuous), race and ethnicity (categorized as non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, Asian, and other), and the median household income for the Census block group of residence for Wave 2. From the Wave 2 activity path data we calculated the proportion of time spent within 100m of any retail outlet, the proportion of time spent within 100m of home, and an index of exposure to neighborhood disorganization. Using 2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates for Census block groups, neighborhood disorganization was the time-weighted average for the sum of: overall unemployment, households receiving public assistance, low income persons (< 100% poverty level), low income persons (100–149% poverty level), high school dropouts, female-headed households, renter-occupied houses, and moved in the previous year.

The sources through which adolescents accessed alcohol were taken from the Wave 3 annual survey. We asked participants, “Thinking about the last 12 months, when you had at least one whole drink, how did you get alcoholic beverages?” Response frequencies are presented in Table 1. We grouped responses as retail access, home access, access from a peer aged ≥ 21 years, and access from a peer aged < 21 years.

Table 1.

Response frequencies for measures of alcohol access, Wave 3 annual survey; n = 168.

| Alcohol Source | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Store Access | 8 | 4.8 |

| I bought it myself with a fake ID | 1 | 0.6 |

| I bought it myself without a fake ID | 1 | 0.6 |

| I took it from a store or shop | 3 | 1.8 |

| A stranger bought it for me | 2 | 1.2 |

| “Took it from homeless” | 1 | 0.6 |

| Home Access | 45 | 26.8 |

| I got it from a brother or sister | 5 | 3.0 |

| I got it from home with my parents’ permission | 31 | 18.5 |

| I got it from home without my parents’ permission | 21 | 12.5 |

| I got it from another relative | 9 | 5.4 |

| “I took it from my uncle’s house without permission” | 1 | 0.6 |

| “Open bar at a wedding” | 1 | 0.6 |

| Peer Access (21+) | 21 | 12.5 |

| I got it from someone I know aged 21 or older | 21 | 12.5 |

| Peer Access (<21) | 39 | 23.2 |

| I got it from someone I know under age 21 | 9 | 23.2 |

Note that responses may not sum to the observed total within each category because the participants were able to select multiple responses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

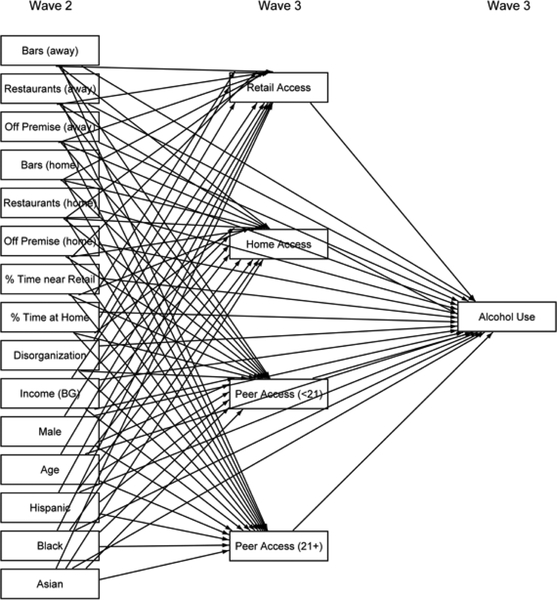

Path analyses using generalized structural equation models related neighborhood conditions, alcohol access, and alcohol use. Separate models assessed each alcohol use outcome (e.g. frequency, volume). A fully saturated model is presented in Figure 1. We specified the alcohol source variables as binary and fit binomial regressions with logit links, and specified the alcohol use variables as counts and fit negative binomial regressions with log links. We used a stepwise procedure in which we first estimated the saturated models, then removed all paths with p > 0.1. Variables not connected to any other variables through remaining paths were removed from the model. We then estimated the trimmed models. Conventional fit statistics for structural equation models (e.g. RMSEA) are not available for the generalized variant of these models (Lombardi et al., 2017), so model specification was assessed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) statistics. Similarly, the covariance structure of the independent variables cannot be explicitly included in the generalized structural equation models (Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh, 2004), so we inspected a correlation matrix and conducted sensitivity analyses in which we removed variables that were correlated at r > 0.7. The main analyses used exposure to alcohol outlets away from home using the 100m buffer, and exposure to alcohol outlets near home using Census block groups. Additional sensitivity analyses tested exposure to alcohol outlets away from home using the 50m and 200m buffers; tested exposure to alcohol outlets at home using tracts; combined retail access with home access (to test for possible bias due to a low frequency of adolescents accessing alcohol through retail sources); measured exposure to alcohol outlets during Wave 3 instead of Wave 2; omitted 15 participants who moved residences between Wave 2 and Wave 3; and included controls for census block group land area so as to assess effects for alcohol outlet density per square mile. Spatial data processing was performed using ArcGIS v10.3.6, and statistical analyses were performed using Stata v15.

Figure 1.

Saturated generalized structural equation model linking exposure to alcohol outlets and relevant covariates (wave 2) to alcohol access (wave 3), and exposure to alcohol outlets and alcohol access to alcohol use (wave 3).

3. Results

Complete data were available for 168 participants, whom we tracked using GPS track for a mean of 598.7 hours per person (SD = 113.1) during Wave 2 and who travelled a mean of 1,560.2 kilometers per person (SD = 734.2). Table 2 shows the summary statistics for all included variables. Demographic characteristics are similar to the demographic profile of the San Francisco Bay Area; there were 66 (39.2%) males, 88 (52.4%) non-Hispanic Whites, 33 (19.6%) Hispanics, 21 (12.5%) Blacks and 11 (6.6%) Asians. In the Wave 3 annual survey, 45 (27.3%) participants reported consuming alcohol. The mean 30-day drinking frequency for all participants was 1.1 days (SD = 2.9), and all participants consumed a mean of 1.0 drinks (SD = 2.1) on drinking days. Participants reported getting drunk a mean of 0.5 days (SD = 1.4), and 0.4 (SD = 1.2) days of binging.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for included variables; n = 168

| Variable Name | Description | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to Retail Alcohol Outlets - Away from Home (Wave 2) | |||||

| Bars (Away) | Bars per hour in Wave 2 GPS activity path, excluding within 100m of home point | 6.2 | 18.0 | 0.0 | 143.8 |

| Restaurants (Away) | Restaurants per hour in Wave 2 GPS activity path, excluding within 100m of home point | 35.8 | 60.8 | 0.9 | 537.8 |

| Off Premise Outlets (Away) | Off premise outlets per hour in Wave 2 GPS activity path, excluding within 100m of home point | 17.5 | 39.3 | 0.1 | 419.8 |

| Exposure to Retail Alcohol Outlets - Near Home (Wave 2) | |||||

| Bars (Home) | Bars in home block group | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 11.0 |

| Restaurants (Home) | Restaurants in home block group | 1.4 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 30.0 |

| Off Premise Outlets (Home) | Off premise outlets in home block group | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Exposure to Social Environmental Conditions (Wave 2) | |||||

| % Time near Retail | Percent of time spent within 100m of any retail outlet during Wave 2 GPS activity path | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 4.3 |

| % Time at Home | Percent of time spent within 100m of home during Wave 2 GPS activity path | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Disorganization | Time weighted exposure to neighborhood disorganization during Wave 2 GPS activity path (calculated using block groups) | 94.4 | 50.2 | 25.1 | 281.4 |

| Income (BG) | Median household income for block group of residence | 102632.4 | 42263.2 | 31028.0 | 232679.0 |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Male | Male | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Age | Age in years at Wave 2 annual survey (continuous) | 16.8 | 0.8 | 16.0 | 18.0 |

| White | Non-Hispanic White | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Hispanic | Hispanic | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Black | Non-Hispanic Black | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Asian | Asian | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Alcohol. Access (Wave 3) | |||||

| Store Access | Accessed alcohol from any retail outlet in previous 12 months | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Home Access | Accessed alcohol from home in previous 12 months | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Peer Access (21+) | Accessed alcohol from a friend aged ≥ 21 years in previous 12 months | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Peer Access (<21) | Accessed alcohol from a friend aged < 21 years in previous 12 months | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Alcohol Consumption (Wave 3) | |||||

| Frequency | Estimated number of days consumed alcohol in last 30 days | 10.9 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 24.0 |

| Quantity | Estimated number of drinks consumed on each drinking day in last 30 days | 1.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 12.0 |

| Drunk | Estimated number of days drunk on alcohol in last 30 days | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 8.0 |

| Binge | Estimated number of days binged on ≥ 4 drinks in last 30 days | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

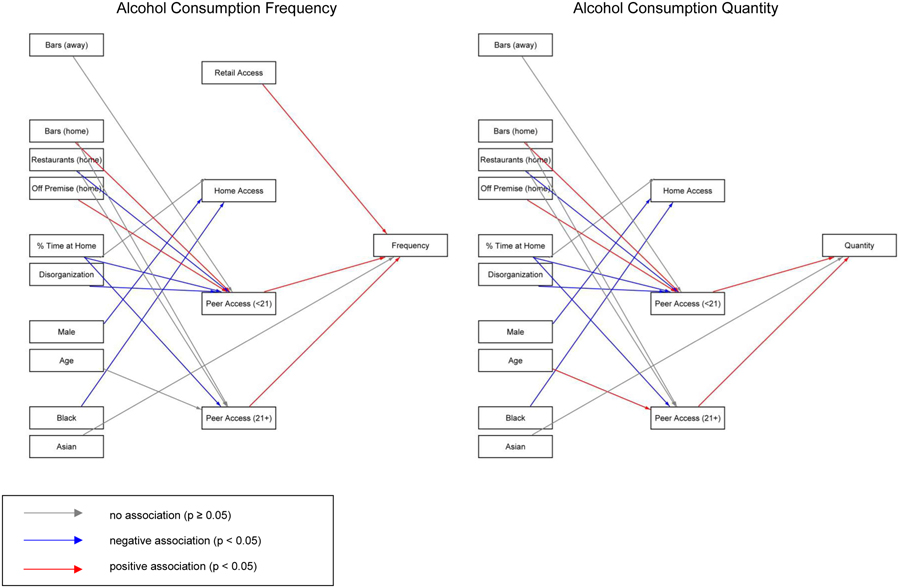

The trimmed generalized structural equation models for 30-day drinking frequency and 30-day drinking quantity are presented in Figure 2. Both models retained the measures of exposure to bars away from home and exposure to bars, restaurants, and off-premise outlets near home. All four alcohol sources were retained in the model for drinking frequency, and retail access was omitted from the model for drinking quantity. Assessed using AIC and BIC, the model fit improved between the saturated and trimmed models in all cases (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Results for trimmed generalized structural equation models.

Table 3.

Fit statistics for generalized structural equation models

| Alcohol Use Measure | Model | ll(model) | df | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Saturated | −424.3 | 85 | 1018.7 | 1287.7 |

| Trimmed | −409.7 | 22 | 863.3 | 933.0 | |

| Quantity | Saturated | −433.8 | 85 | 1037.6 | 1306.6 |

| Trimmed | −424.5 | 21 | 890.9 | 957.4 | |

| Drunk | Saturated | −366.3 | 85 | 902.6 | 1171.6 |

| Trimmed | −355.3 | 21 | 752.7 | 819.1 | |

| Binge | Saturated | −357.6 | 85 | 885.2 | 1154.2 |

| Trimmed | −341.8 | 21 | 725.5 | 792.0 |

Point estimates for these trimmed models are suppressed for ease of interpretation, but the direction of the association is shown by color coding (online version only; see legend for black and white print version). In both the drinking frequency and drinking quantity models, red paths (indicating positive associations with p < 0.05) link exposure to bars and off-premise outlets near home to alcohol access through a peer aged < 21, which in turn predicts alcohol consumption. There is no path between exposure to alcohol outlets and alcohol consumption. Alcohol access through stores and through peers aged ≥ 21 years predict drinking frequency, and access through peers aged ≥ 21 years predicts drinking quantity. In both models, blue paths (indicating negative associations with p < 0.05) link a greater proportion of time spent at home and greater exposure to neighborhood disorganization to less alcohol access through peers aged < 21. Trimmed models for the 30-day measures of days drunk and days binge drinking are shown in Supplementary Figure S1*, and results are similar to the two models for drinking quantity and drinking frequency.

There was some inconsistency between the results for these main models and the sensitivity analyses that used different geographic boundaries to delineate exposures at home and exposure away from home (Supplementary Figure S2)†. The retained structure of the trimmed models remained similar, and exposure to off-premise outlets was associated with alcohol access through peers aged < 21 years in most cases; but exposure at home assessed within Census tracts (vs. block groups) showed links between bars near home and alcohol access through peers aged ≥ 21 years. Likewise, omitting 15 participants who had a residential move between Wave 2 and Wave 3 led to some key associations falling outside statistical significance. Combining home sources with retail sources, adding controls for land area, using exposure measures from Wave 3, and combining home and retail access measures did not materially affect study results.

4. Discussion

Alcohol access and consumption are both illegal and common for adolescents aged under 21 years in the United States. Because alcohol consumption during adolescence is associated with increased problems during adolescence (such as injury, offending, regretted sex) (Bellis et al., 2009; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2016; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012) and in later life (such as alcohol use disorders) (Grant, 1998; Wells et al., 2004), studies identifying the factors that contribute to adolescent access and consumption can inform preventive interventions and benefit public health. In this longitudinal path analysis of adolescents from 10 cities in the San Francisco Bay Area, exposure to bars and off-premise outlets near home is associated with accessing alcohol through peers aged under 21, which is in turn associated with increased alcohol consumption. Results were mostly consistent across different alcohol consumption measures, including the frequency of use, the volume consumed, the frequency of binging, or the frequency of drunkenness.

Our results are consistent with prior studies of neighborhood conditions, alcohol access, and alcohol consumption. Specifically, associations have been detected previously between living near alcohol outlets and access through peers (Chen et al., 2009), and between access through peers and increased consumption (Dent et al., 2005). Other longitudinal studies (Rowland et al., 2016; Tobler et al., 2009; Tobler et al., 2011) have identified similar paths to those found here. These collective studies provide preliminary evidence regarding distal causes of adolescents’ alcohol consumption (McMichael, 1999), beyond proximate causes such as being given alcohol by a friend. Adolescents who encounter alcohol outlets during routine activities may consider alcohol consumption to be normative behavior, and may be more willing to consume alcohol. Adolescents’ self-perceptions are closely and rigidly linked to their routine activities and their peer affiliations, and the neighborhoods they routinely encounter shape behavioral norms (Boardman and Saint Onge, 2005; Pasch et al., 2009; Reboussin et al., 2011), so outlets encountered near home may affect these pathways to a greater extent than outlets encountered elsewhere in their activity space. At the same time, the presence of more outlets contributes to greater “flow” of alcohol through neighborhoods (Treno et al., 2008), including for peers for whom access is easier (either directly through retail outlets or indirectly, for example through their own homes). We controlled for neighborhood income and exposure to neighborhood disorganization, so our results provide stronger evidence for this normative behaviors explanation than the alternate explanation that, because alcohol outlets tend to be located in lower income and socially disorganized areas, weaker social controls contribute to deviant behavior including alcohol consumption.

These findings have clear implications for preventive interventions. Most strategies to reduce adolescents’ alcohol consumption focus on reducing direct access through retail sources (Dent et al., 2005; Flewelling et al., 2013; Grube, 1997; Joris et al., 2012; Preusser and Williams, 1992; Rammohan et al., 2011; Wagenaar et al., 2000). For example, reward and reminder programs that encourage retailers to adhere to minimum purchase age laws can achieve reductions in adolescent access (Grube, 1997; Treno et al., 2007; Wagenaar et al., 2005). Such interventions are predicated on community systems theory, which proposes that communities are complex adaptive systems and that affecting global change requires intervening upon the social, economic, and physical environmental contexts within which individuals interact (Holder, 1998, 2000). Limiting direct access through retail outlets is a necessary component of a systems-based prevention approach, but it is clearly not sufficient. Further interventions are necessary to disrupt the link between exposure to alcohol outlets, alcohol access, and alcohol use. For example, published studies provide strong evidence that adolescents consume more alcohol when they are exposed to more alcohol advertising (Naimi et al., 2016) and that perceived norms mediate this association (Davis et al, 2019). Neighborhood exposure to alcohol outlets may affect consumption through the same mechanism—that is, with exposure to alcohol signage functioning as a form of advertising—and could therefore be a viable target for intervention. Having less prominent alcohol signage could thus limit exposure to alcohol in the environment (Collins et al., 2007; Grube and Wallack, 1994; Martin et al., 2002), and could thereby reduce adolescent alcohol consumption. Our findings also implicate direct access to alcohol through social networks, suggesting that preventive intervention should seek to disrupt the connection between exposure and access (Arria et al., 2014; Fell et al., 2016). For example, social host laws impose liability on of-age hosts when alcohol is served to a minor at a private residence, including liability for subsequent alcohol-related harms (e.g. motor vehicle crashes).

This analysis has several strengths. Exposures to alcohol outlets near home were separated from those away from home. Analyses were conducted within rather than across individuals. Data were longitudinal, ensuring temporal agreement between the associations and the theoretical mechanisms. However, we acknowledge some important limitations. Our results were slightly unstable when we used different measures of exposure to alcohol outlets, which may be due to our small sample size or because exposures at different geographic scales contribute differently to alcohol access and alcohol consumption. Our convenience sample of adolescents may not be representative of adolescents in the San Francisco Bay Area or elsewhere. Although the study sample had a similar demographic composition to the source population, was recruited within a careful spatial sample frame, and had comparable alcohol consumption to other population-based samples of similarly aged adolescents (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018), it is possible that generalizability was affected. The loss to follow-up could also have biased results in either direction. Finally, although our longitudinal design is a key strength, the precise temporal scale over which exposure to alcohol outlets affect adolescents’ alcohol consumption is not clear. Prior studies using longitudinal designs have generally used one-year intervals between the exposure and the outcome (Rowland et al., 2016; Tobler et al., 2009), apart from Tobler et al (2011) who used a one-year interval between exposures and then a four-year interval between the exposures and alcohol consumption. We collected data at 1-year intervals to ensure consistency within this literature, although it is possible that alternate intervals would yield different results.

5. Conclusion

Alcohol consumption is both illegal and common for adolescents. This study and many others that have considered paths connecting neighborhood conditions, alcohol access, and alcohol consumption indicate that exposure to alcohol outlets contribute to greater alcohol access through peers, and that alcohol access through peers contributes to greater alcohol consumption. Environmental strategies that interrupt these paths may reduce adolescents’ alcohol consumption and benefit public health.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Combines survey and GPS data to measure alcohol exposure, access and consumption

Uses generalized structural equation models to examine interrelationships

Finds exposure to outlets near home predicts alcohol access through peers aged < 21

Finds alcohol access through peers aged < 21 predicts increased consumption

Detects no direct association between exposure to outlets and consumption

Role of Funding Source

This study was funded by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R01HD078415-01A1) and the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K01AA026327-01A1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107622

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107622

References

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Moshkovich O, Bugbee BA, Vincent KB, O’Grady KE, 2014. Providing alcohol to underage youth: the view from young adulthood. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 38, 1790–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, Grube JW, Hill L, Holder HD, Homel R, Livingston M, Osterberg E, Rehm J, Room R, Rossow I, 2010. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy, 2nd ed Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Phillips-Howard PA, Hughes K, Hughes S, Cook PA, Morleo M, Hannon K, Smallthwaite L, Jones L, 2009. Teenage drinking, alcohol availability and pricing: a cross-sectional study of risk and protective factors for alcohol-related harms in school children. BMC Public Health. 9, 380–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin M, Lipperman-Kreda S, Mair C, Grube J, Gruenewald P, 2016. Identifying strategies to limit youth drinking in the home. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 77(6), 943–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman J, Saint Onge J, 2005. Neighborhoods and adolescent development. Child. Youth Environ. 15, 138–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt H, Toomey TL, Dunsmuir W, Wagenaar AC, 2006. Propensity for and correlates of alcohol sales to underage youth. J. Alcohol Drug. Educ 50, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, Zhang J-F, 1997. Access to alcohol from licensed premises during adolescence: a longitudinal study. Addiction. 92, 737–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2012. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2010 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2018. 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M-J, Gruenewald PJ, Remer LG, 2009. Does alcohol outlet density affect youth access to alcohol? J. Adolescent Health. 44, 582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, McCaffrey D, Hambarsoomians K, 2007. Early adolescent exposure to alcohol advertising and its relationship to underage drinking. J. Adolescent Health. 40, 527–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JP, Pedersen ER, Tucker JS, Dunbar MS, Seelam R, Shih R, D’Amico EJ, 2019. Long-term associations between substance use-related media exposure, descriptive norms, and alcohol use from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 1311–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent CW, Grube JW, Biglan A, 2005. Community level alcohol availability and enforcement of possession laws as predictors of youth drinking. Prev. Med 40, 355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch AR, Steinley D, Sher KJ, Slutske WS, 2017. Who’s got the booze? the role of access to alcohol in the relations between social status and individual use. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 78, 754–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser M, Clayton H, Demissie Z, Kanny D, Brewer R, 2017. Current and binge drinking among high school students - United States, 1991–2015. MMWR-Morbid. Mortal. W 66, 474–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell JC, Scherer M, Thomas S, Voas RB, 2016. Assessing the Impact of Twenty Underage Drinking Laws. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 77, 249–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling RL, Grube JW, Paschall MJ, Biglan A, Kraft A, Black C, Hanley S, Ringwalt C, Ruscoe J, 2013. Reducing youth access to alcohol: findings from a community-based randomized trial. Am. J. Community Psychol. 51, 264–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley K, Altman D, Durant R, Wolfson M, 2004. Adults’ approval and adolescents’ alcohol use. J. Adolescent Health. 35, 345.e317–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster J, McGovern P, Wagenaar A, Wolfson M, Perry CL, Anstine P, 1994. The ability of young people to purchase alcohol without age identification in northeastern Minnesota, USA. Addiction 89, 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster J, Murray D, Wolfson M, Wagenaar AC, 1995. Commercial availability of alcohol to young people: results of alcohol purchase attempts. Prev. Med 24, 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Gruenewald P, Treno AJ, Lee J, 2003. Evaluating Alcohol Access and the Alcohol Environment in Neighborhood Areas. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 27, 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C, Kypri K, Johnson N, Lynagh M, Love S, 2012. Parental supply of alcohol and adolescent risky drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 31, 754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman D, Speer P, 1997. The concentration of liquor outlets in an economically disadvantaged city in the northeastern United States. Subst. Use Misuse. 32, 2033–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselt JF, Van Hoof JJ, De Jong MD, 2012. Why should I comply? Sellers’ accounts for (non-)compliance with legal age limits for alcohol sales. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 7, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, 1998. The impact of a family history of alcoholism on the relationship between age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Alcohol Health Res. W 22, 144–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube JW, 1997. Preventing sales of alcohol to minors: results from a community trial. Addiction. 92, S251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube JW, Wallack L, 1994. Television beer advertising and drinking knowledge, beliefs, and intentions among schoolchildren. Am. J. Public Health. 84, 254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald P, Remer LG, LaScala E, 2014. Testing a social ecological model of alcohol use: the California 50-city study. Addiction. 109, 736–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, 2007. The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: niche theory and assortative drinking. Addiction. 102, 870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Park E, 2000. The relative importance of social versus commercial sources in youth access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Prev. Med 31, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearst MO, Fulkerson JA, Maldonado-Molina MM, Perry CL, Komro KA, 2007. Who needs liquor stores when parents will do? The importance of social sources of alcohol among young urban teens. Prev. Med 44, 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, 1998. Alcohol and the Community: A Systems Approach to Prevention. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, 2000. Community Prevention of Alcohol Problems. Addict. Beh 25, 843–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2019). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975–2018: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Bell M, Hay G, Baxter J, 2008. Alcohol outlet density and university student drinking: a national study. Addiction. 103, 1131–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi S, Santini G, Marchetti GM, Focardi S, 2017. Generalized structural equations improve sexual-selection analyses. Plos One. 12, e0181305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynne-Landsman SD, Kominsky TK, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC, Komro KA, 2016. Alcohol sales to youth: data from rural communities within the Cherokee Nation. Prev. Sci 17, 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Snyder L, Hamilton M, Fleming-Milici F, Slater M, Stacy A, Chen M-J, Grube JW, 2002. Alcohol advertising and youth. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 26, 900–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael A, 1999. Prisoners of the proximate: Loosening the constraints on epidemiology in an age of change. Am J. Epidemiol 149, 887–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morleo M, Cook PA, Bellis MA, Smallthwaite L, 2010. Use of fake identification to purchase alcohol amongst 15–16 year olds: a cross-sectional survey examining alcohol access, consumption and harm. Subst. Abuse Treat. Pr 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison CN, Byrnes HF, Miller BA, Kaner E, Wiehe SE, Ponicki WR, Wiebe DJ, 2019. Assessing individuals’ exposure to environmental conditions using residence-based measures, activity location–based measures, and activity path–based measures. Epidemiology. 30, 166–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison CN, Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, 2015. Socioeconomic determinants of exposure to alcohol outlets. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 76, 439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch K, Hearst MO, Nelson M, Forsyth A, Lytle L, 2009. Alcohol outlets and youth alcohol use: exposure in suburban areas. Health Place. 15, 642–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall M, Grube J, Black C, Flewelling R, Ringwalt C, Biglan A, 2007. Alcohol outlet characteristics and alcohol sales to youth: results of alcohol purchase surveys in 45 Oregon communities. Prev. Sci 8, 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preusser D, Williams A, 1992. Sales of alcohol to underage purchasers in three New York counties and Washington, D.C. J. Public Health Pol. 13, 306–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2016. Alcohol and Public Health: Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Retrieved March 13, 2019 from: https://nccd.cdc.gov/DPH_ARDI/default/default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Ross CS, Siegel MB, DeJong W, Jernigan DH, 2016. Amount of televised alcohol advertising exposure and the quantity of alcohol consumed by youth. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 77, 723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Song E-Y, Wolfson M, 2011. The impact of alcohol outlet density on the geographic clustering of underage drinking behaviors within census tracts. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 35, 1541–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B, Evans-Whipp T, Hemphill S, Leung R, Livingston M, & Toumbourou JW, 2016. The density of alcohol outlets and adolescent alcohol consumption: An Australian longitudinal analysis. Health Place. 37, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R, Farrow J, Banks B, Giesel A, 1998. Use of false ID cards and other deceptive methods to purchase alcoholic beverages during high school. J. Addict Dis. 17, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Mason K, Theall K, Simonsen N, Schneider S, Towvim L, DeJong W, 2008. The contextual role of alcohol outlet density in college drinking. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 69, 112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C, McKay H, 1942. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Sherk A, Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T, Andreasson S, Angus C, Gripenberg J, Holder H, Holmes J, Makela P, Mills M, Norstrom T, Ramstedt M, Woods J, 2018. Alcohol consumption and the physical availability of take-away alcohol: systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the days and hours of sale and outlet density. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 79, 58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S, 2004. Generalized linear latent and mixed models with composite links and exploded likelihoods, in: Biggeri A, Dreassi E, Lagazio C, Marchi M (Eds.), Proceedings of the 19th International Workshop on Statistical Modeling. Firenze University Press, Florence, Italy, pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stogner J, Martinez JA, Miller BL, Sher KJ, 2016. How strong is the “fake id effect?” An examination using propensity score matching in two samples. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 40, 2648–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall K, Scribner R, Cohen D, Bluthenthal R, Schonlau M, Farley T, 2009. Social capital and the neighborhood alcohol environment. Health Place. 15, 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM, 2009. Relationship between neighborhood context, family management practices and alcohol use among urban, multi-ethnic, young adolescents. Prev. Sci 10, 313–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Livingston MD, Komro KA, 2011. Racial/ethnic differences in the etiology of alcohol use among urban adolescents. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 72, 799–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Komro KA, Oakes JM, Lenk KM, 2008. Propensity for illegal alcohol sales to underage youth in Chicago. J. Commun. Health 33, 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treno AJ, Grube JW, Martin S, 2003. Alcohol availability as a predictor of youth drinking and driving: a hierarchical analysis of survey and archival data. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 27, 835–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treno AJ, Gruenewald P, Lee J, Remer LG, 2007. The Sacramento Neighborhood Alcohol Prevention Project: Outcomes from a community prevention trial. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs. 68, 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treno AJ, Ponicki WR, Remer LG, Gruenewald PJ, 2008. Alcohol outlets, youth drinking, and self-reported ease of access to alcohol: a constraints and opportunities approach. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 32, 1372–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong KD, Sturm R, 2009. Alcohol environments and disparities in exposure associated with adolescent drinking in California. Am. J. Public Health. 99, 264–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof JJ, Gosselt JF, Baas N, De Jong MDT, 2012. Improving shop floor compliance with age restrictions for alcohol sales: effectiveness of a feedback letter intervention, Eur. J. Public Health. 22, 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward BM, Snow PC, 2011. Factors affecting parental supply of alcohol to underage adolescents. Drug Alcohol Rev. 30, 338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Murray D, Gehan J, Wolfson M, Forster J, Toomey TL, Perry CL, Jones-Webb R, 2000. Communities mobilizing for change on alcohol: outcomes from a randomized community trial. J. Studies Alcohol. 61, 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Erickson D, 2005. Preventing youth access to alcohol: outcomes from a multi-community time-series trial. Addiction. 100, 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Murray D, Short B, Wolfson M, Jones-Webb R, 1996. Sources of alcohol for underage drinkers. J. Studies Alcohol. 57, 325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J, Horwood L, Fergusson D, 2004. Drinking patterns in mid-adolescence and psychosocial outcomes in late adolescence and early adulthood. Addiction. 99, 1529–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.