Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The poor maternal oral health in the pregnancy has an impact on the fetus through the oral-systemic link. Various studies have proven the relationship between poor maternal oral health and the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Hence, periodontal therapy becomes indispensable during pregnancy. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis conducted to assess the influence of periodontal therapy on the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes have shown inconsistent results. Hence, we conducted the present review to assess the influence of periodontal therapy on the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes including the studies published till date.

Materials and Methods:

We searched for the relevant studies using the databases PUBMED, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and EMBASE on the randomized controlled trials evaluating the influence of periodontal treatment on adverse pregnancy outcomes from 2000 to 2018. Nineteen studies were considered for the present review based on the predetermined criteria. The risk of bias tool by Cochrane was used to evaluate the risk of bias among the studies.

Results:

Among the studies included for the present review, the occurrence of preterm birth among the pregnant mothers who received periodontal therapy ranged from 0% to 53.5%, while in the control group, the range was 6.38%–72%. The rate of LBW among the mothers treated for periodontal disease ranged from 0% to 36%, and in the control group, it varied from 1.15% to 53.9%.

Conclusion:

With best possible evidence, it can be inferred that nonsurgical periodontal therapy is safe during pregnancy. Even though it does not completely avert the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes, it can be recommended as a part of antenatal care.

Key words: Low birth weight, periodontal disease, periodontal therapy, pregnancy outcomes, preterm birth, preterm low birth weight

INTRODUCTION

Adverse pregnancy outcomes (preterm birth [PTB], low birth weight [LBW], and preterm LBW [PTLBW]) remain an important public health problem as it is still encountered across several communities globally and pose a considerable challenge to health professionals. PTB is defined as live birth <37 weeks of gestation, and LBW was defined by the World Health Organization in 1976 as a birth weight lower than 2500 g. The proven risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes were young and advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, previous PTB, short cervix, low educational status, stress, diabetes, short interpregnancy interval, and fetal genotype.[1] Poor maternal health also plays an important role in the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Periodontitis is a chronic destructive inflammatory disease affecting the supporting structures of the tooth which is initiated by the dental plaque with the predominance of Gram-negative anaerobic microorganisms and also mediated by the host inflammatory response. The transit of periodontal pathogens and inflammatory mediators from the periodontal pocket to the fetal placental unit triggering inflammatory cascade could be a plausible link between the periodontal disease and the occurrence of the adverse pregnancy outcomes. This association is inconsistent as shown in previous epidemiological studies.[2,3,4,5]

Various epidemiological studies have shown that periodontal therapy during pregnancy reduces the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[2,6,7,8] Preventive strategies implemented during the antenatal period have shown to improve pregnancy outcomes and oral health. Recommendations from health experts suggest women to undergo dental examination and therapeutic intervention during the preconception stage and during pregnancy.[9] However, the consensus statement of the (European Federation of Periodontology-American Academy of Periodontology) EFP-AAP workshop concluded periodontal therapy during pregnancy with or without systemic antibiotics, does not reduce the overall rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[10]

Several systematic reviews and meta-analysis conducted to assess the effect of periodontal therapy on the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes among mothers with poor oral health have yielded inconclusive results.[11,12] The discordant results can be attributed to the low quality of the trials and the inclusion of only few published studies. The methodologies used to assess the quality of the studies included were also controversial. Moreover, the previous reviews focused on studies published from 2000 to 2012. Considering the abovementioned limitations and the time gap in the literature, we conducted a systematic review to provide the best possible evidence for the plausible association between periodontal therapy and adverse pregnancy outcomes among pregnant mothers with poor oral health. We included the studies published until 2018 for this present review.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) offer the best possible evidence for assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic procedures. Hence, we included all the RCTs that assessed the influence of periodontal therapy at least on any one of these adverse pregnancy outcomes (PTB, LBW, and PTLBW). Reviews, case reports, editorials, in vitro studies, commentaries, animal studies, qualitative studies, case–control studies, cohort studies, and studies reported in other languages except English were excluded from this review. Only full-text articles were included for the present review.

Types of intervention

Scaling and root planning

Oral hygiene instructions and maintenance therapy

Adjunctive use of antibiotics.

Types of outcome measures

PTB

LBW

PTLBW.

Search strategy

We searched for the relevant studies using the databases PUBMED, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and EMBASE on the RCTs evaluating the influence of periodontal treatment on adverse pregnancy outcomes from January 2000 to October 2018. The keywords used for searching the studies were periodontitis, adverse pregnancy outcomes, periodontal therapy, and periodontal treatment, PTB, LBW and PTLBW. Relevant articles were also hand searched.

Study selection and data extraction

The eligibility for the inclusion of the studies for the present review was assessed by two reviewers independently. The reviewers appraised the full text of the studies which assessed the influence of periodontal therapy on any one of the three adverse pregnancy outcomes (PTB, LBW, and PTLBW). The data were extracted from the studies by each reviewer independently which included information about the study design, study population, timing of intervention, and type of intervention and the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes in a separate sheet. Meta-analysis was not done because of heterogeneity attributed to the variations in the timing of periodontal treatment, type of periodontal intervention, and the type of periodontal disease among the studies included in this review.

Quality assessment

Cochrane collaboration tool for assessing the risk of bias was used to assess the quality of the studies included in this review.[13] The tool helps to determine the internal validity of an intervention; usually, a treatment to control or eliminate a disease or a preventive measure to reduce the risk of having the disease. The source of bias in each study was independently appraised by two reviewers and judged as having an unclear, high, or low risk of bias. No study was excluded based on the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Risk of bias in the studies included for review

Among the nineteen studies, thirteen studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] have reported adequate randomization while allocation concealment was reported only in seven studies.[4,7,17,18,20,21,22] Proper blinding of the participants and personnel was done in eight studies.[3,6,7,15,16,17,22,23] The outcome was assessed by the blinded investigator in eight studies.[6,7,15,16,17,21,23,24] Eleven studies [4,5,6,15,17,18,19,21,24] were categorized having a low risk of bias based on incomplete data. Twelve studies [3,4,5,6,12,14,15,16,18,19,22,25] discussed the study outcomes in a prespecified way [Table 1]. Majority of the studies have not explicitly explained about the adjustment of confounders such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, history of PTB, bacterial vaginosis, gestational diabetes, prenatal care, and maternal weight gain except for six studies [3,15,16,19,21,23] which controlled for the majority of confounders. This is one of the methodological characteristics used for the assessment of individual trials based on Cochrane collaboration tool.

Table 1.

Quality of the studies assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool

| Author/years | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| López et al./2002[15] | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jeffcoat et al./2003[7] | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| López et al./2005[21] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Michalowicz et al./2006[3] | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Offenbacher et al./2006[22] | Low | Unclear | Low | High | High | Low |

| Sadatmansouri et al./2006[8] | Low | High | High | High | Unclear | Low |

| Tarannum and Faizuddin/2007[14] | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low |

| Gazolla et al./2007[2] | Unclear | High | High | High | High | Low |

| Newnham et al./2009[19] | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Radnai et al./2009[6] | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Offenbacher et al./2009[16] | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Macones et al./2010[17] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Sant’Ana et al./2011[24] | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High |

| Oliveira et al./2011[23] | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Pirie et al./2013[4] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Weidlich et al./2013[18] | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Reddy et al./2014[5] | Low | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Low |

| Khairnar et al./2015[20] | Low | Low | High | Unclear | High | High |

| Penova-Veselinovic et al./2015[25] | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High | Low |

RESULTS

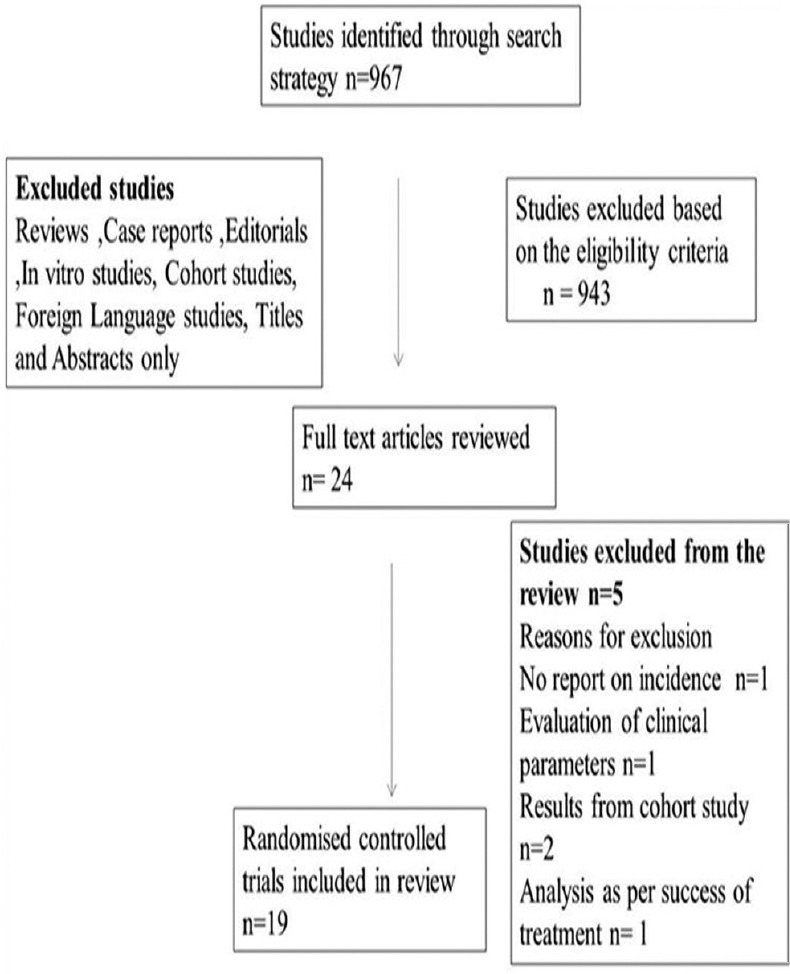

Total studies identified through the database search were 967. After assessing the studies for the eligibility criteria, 24 studies considering the title and abstract were selected for full-text reading [Figure 1]. Five studies have been excluded as they did not report the incidence of birth outcomes,[26] did not evaluate clinical parameters,[27] participants were from a part of a cohort study,[28,29] and results of the study were analyzed as per the success of periodontal treatment.[30]

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting the process of literature search

Patient characteristics

About 8761 pregnant women were included in 19 trials. The majority of participants in the trials included were in the second trimester of pregnancy. The mean age of the participants was 25.6 ± 2.5 years [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the studies included in the review

| Author/Year | Country | Total number of subjects | Timing of intervention | Pregnancy outcome | Odds ratio/Relative risk/Incidence/Risk ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Lopez/2002[15] | Chile | Treatment group - 200 Control group -200 |

9-21 weeks | PTLBW LBW PTB |

OR -6.67 (1.89-23.52) OR -6.96 (0.81-59.62) OR-6.11 (1.3-28.53) |

| 2.Jeffcoat/2003[7] | USA | Treatment group- 246 Control group- 120 |

21-25 weeks | PTB | OR-0.45 (0.15-1.28)/ RR-1.4 (0.7-2.9) |

| 3.Lopez/2005[21] | Chile | Treatment group-580 Control group-290 |

28 weeks | PTB LBW PTLBW |

OR-4.11 (1.73-9.73) OR-1.47 (0.32-6.54) OR-3.26 (1.56-6.83) |

| 4.Michalowicz/2006[3] | USA | Treatment group -413 Control group-412 |

13-17 weeks | PTB LBW |

Risk ratio1.17 (0.74,1.85) Risk ratio0.92 (0.58,1.45) |

| 5.Offenbacher 2006[22] | USA | treatment group-56 Control group-53. |

21 weeks | PTB | OR-0.26 (0.08-0.85) |

| 6.Sadatmonsouri/2006[8] | Iran | Treatment group - 15 Control group-15 |

13-20 week | PTBLBW | RR-0.12 (0.01,2.45) RR-0.31 (0.01,8.28) |

| 7.Gazolla/2007[2] | Brazil | Treatment group-266 Control group-62 |

<22 weeks | PTLBW | 7.5% Incidence |

| 8. Tarrannum/2007[14] | India | Treatment group-100 Control group-100 |

<22 weeks | PTB LBW |

76.4% Incidence 53.9% Incidence |

| 9.Radnai/2009[6] | Hungary | Treatment group-41 Control group-40 |

24 weeks | PTLBW PTB LBW |

OR- 4.6 (1.3-15.5) OR- 3.4 (1.3-8.6) OR - 4.3 (1.5-12.6) |

| 10.Newnham/2009[19] | Australia | Treatment group-538 Control group-540 |

20 weeks | PTB | OR -1.05 (0.7-1.58) |

| 11. Offenbacher/2009[16] | USA | Treatment group-903 Control group-903 |

23 weeks | PTB LBW |

OR-1.22 (0.09-1.66) OR-1.01 (0.72-1.42) |

| 12. Macones/2010[17] | Philadelphia | Treatment group-376 Control group-380 |

NA | PTB PTLBW |

RR - 1.38 (0.92–2.08) RR -1.19 (0.62-2.28) |

| 13.Santana/2011[24] | Brazil | Treatment group-16 Control group-15 |

9-24 weeks | PTB | OR-13.50 (1.47-123.45) |

| 14. Oliveria/2011[23] | Brazil | Treatment group-122 Control group-124 |

12-20 weeks | PTB LBW PTLBW |

RR-0.927 (0.601-1.431) RR-0.735 (0.459-1.179) RR-0.915 (0.561-1.493) |

| 15. Weidlich/2011[18] | Brazil | Treatment group-122 Control group-124 |

12-20 weeks | PTB | RR-1.25 (0.87,1.78) |

| 16. Pirie/2013[4] | Northern ireland | Treatment group-49 Control group-50 |

22 weeks | PTB- LBW- |

RR-4.08 (0.47-35.24) RR-3.06 (0.33-28.43) |

| 17. Reddy/2014[5] | India | Treatment group-49 Control group-50 |

22 weeks | PTB LBW |

10% Incidence 20%Incidence |

| 18.Khairnar/2015[20] | India | Treatment group-50 Control group-50 |

<22 weeks | PTB LBW |

OR -0.54 (0.38-0.77) OR -0.78 (0.50-1.21) |

| 19.Penova vaselinovic/2015[25] | Australia | Treatment group-50 Control group-50 |

<22 weeks | PTB | OR -0.33 (0.04-2.99) |

OR-Odds ratio, RR-Relative risk, NA – Not applicable, PTLBW-Preterm low birth weight, PTB- Preterm birth, LBW-Low birth weight

Population characteristics

The studies were conducted on different countries among homogenous population in Chile,[15,21] Iran,[8] India,[5,14] Hungary,[6] Ireland,[4,11] Brazil [22] and heterogeneous population in U.S.A [3,7,16,17,18,22,23] and Australia.[19] The studies conducted among homogeneous population showed positive influence of periodontal therapy on the reduction of adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to studies done in heterogeneous population.

Study location

When compared to single center trials with a defined population,[6,7,14,15,21,22] multicenter trials with a larger population [3,16,17] showed negative results due to differences among the study population.

Criteria used for defining periodontal disease

The parameters used for assessing the periodontal status in the studies were probing depth, clinical attachment level (CAL), and bleeding on probing. Among the studies included in this review, there is a disparity in the criteria used for defining the periodontal disease. Some studies used CAL as the only criteria [7,14,17,22] to define periodontal disease, whereas other studies [3,5,6,12,21] used combination of probing depth, CAL, and bleeding on probing.

Periodontal intervention

There was heterogeneity among the studies considering the treatment options provided to pregnant mothers. The participants in the treatment group received oral hygiene instructions, full-mouth scaling, and root planning either in a single visit or multivisits and was followed till delivery. Only two studies [7,15] advocated the use of antibiotics as a part of the intervention. However, the results did not show any significant difference over the additional usage of antibiotics. Nine [7,8,14,15,17,18,19,20] of the RCTs used root planning as the only treatment option. The control group in the studies did not receive any active periodontal therapy during pregnancy [Table 3].

Table 3.

Periodontal characteristics of the participants from the studies included for the review

| Author/years | Definition of periodontal disease | Type of periodontal disease | Type of intervention | Conclusion from studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| López et al./2002[15] | 4 teeth with 1 site with PD ≥4 mm and CAL ≥3 mm | Mild to moderate | SRP and rinsing with 0.12% CHX maintenance 2-3 weeks till delivery | Periodontal therapy significantly reduces rates of PLBW |

| Jeffcoat et al./2003[7] | >3 sites with CAL loss ≥3mm | Moderate | SRP and rinsing with CHX maintenance 2-3 weeks till delivery | SRP reduces PTB |

| López et al./2005[21] | ≥25% of sites with BOP and no sites with CAL >2 mm | gingivitis | SRP with 0.12% CHX | Periodontal treatment significantly reduces rate of PTB/LBW |

| Michalowicz et al./2006[3] | PD ≥4 mm and CAL ≥2 mm and BOP at≥35% of tooth sites | Moderate | SRP and OHI till needed till delivery | Periodontal treatment improves periodontal disease but does not alter pregnancy outcomes |

| Offenbacher et al./2006[22] | ≥2 sites with ≥5 mm PD with CAL 1-2 mm ≥1 site and PD ≥5 mm | Mild | SRP with the use of sonic brush | Potential benefits of periodontal treatment on pregnancy outcomes |

| Sadatmonsouri et al./2006[8] | ≥ 4 mm PD at≥4 teeth≥3 mm CAL at same site | Moderate to severe | SRP with 0.12% CHX | Periodontal therapy reduces the PTB rate |

| Gazolla et al./2007[2] | P1 - ≥4 teeth PD 4-5 mm and CAL - 3-5 mm. P2 - ≥4 teeth with PD and CAL of 5-7 mm at the same site. P3 - ≥4 teeth withPD and CAL 7mm at the same site | Moderate to severe | SRP, OHI with 0.12% CHX | Periodontal disease is significantly related to PTLBW |

| Tarannum and Faizuddin/2007[14] | ≥2 mm attachment loss at ≥50% of examined sites | Moderate to severe | SRP with CHX and maintenance every 3-4 weeks | Periodontal therapy reduces the risk of PTB |

| Radnai et al./2009[6] | ≥4 mm PD atleast at one site, BOP for ≥50% of teeth | Mild to moderate | SRP and plaque control | Periodontal treatment completed before 35th week have beneficial effect on birth weight and time of delivery |

| Newnham et al./2009[19] | PD ≥4 mm at ≥12 probing sites | Mild to moderate | SRP with CHX and maintenance every 3 weeks till delivery | Periodontal treatment does not improve pregnancy outcomes |

| Offenbacher et al./2009[16] | ≥20 teeth with ≥3 sites with CAL ≥3 mm | Mild | SRP | Periodontal therapy did not reduce incidence of preterm delivery |

| Macones et al./2010[17] | CAL ≥3 mm on ≥3 teeth and ≥5 mm on ≥3 teeth | Moderate to severe | SRP | Periodontal treatment does not reduce the incidence of pregnancy outcomes |

| Sant’Ana et al./2011[24] | NA | NA | SRP and OHI | Periodontal treatment during second trimester did not reduce the risk for PTB, LBW and PTLBW |

| Oliveira et al./2011[23] | 4 or more teeth with one or more sites with PD ≥4 mm and CAL ≥3 mm | Mild to moderate | SRP with maintenance every 3 weeks till delivery | Periodontal treatment during second trimester reduces the risk for PTB, LBW and PTLBW |

| Weidlich et al./2011[18] | 4 or more teeth with one or more sites with PD ≥4 mm and CAL ≥3 mm | Mild to moderate | SRP with maintenance every 3 weeks till delivery | Periodontal treatment during second trimester reduces the risk for PTB, LBW and PTLBW |

| Pirie/2013[4] | ≥4 mm at 4 or more sites and CAL ≥at 4 or more sites | Mild to moderate | SRP | Nonsurgical periodontal therapy completed at 20-24 weeks did not reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes |

| Reddy et al./2014[5] | Loss of attachment ≥1 mm, PPD ≥4 mm at 3 to 4 sites in >4 teeth | Mild to moderate | SRP | Treatment reduces pregnancy outcomes |

| Khairnar et al./2015[20] | PD >2 mm, CAL at 50% examined sites | Mild to moderate | SRP with 0.2% CHX rinse once a day | Nonsurgical periodontal therapy can significantly reduce the risk of PTB and LBW deliveries |

| Penova-Veselinovic et al./2015[25] | PD ≥3.5mmat 25% of sites | Mild to moderate | Nonsurgical debridement of sub and supragingival calculus and overhanging restoration | Periodontal disease treatment in pregnancy improves periodontal parameters with no effect on pregnancy outcome |

NA – Not applicable; SRP – Scaling and root planning; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; BOP – Bleeding on probing; RR – Relative risk; PTB – Preterm birth; LBW – Low birth weight; PTLBW – Preterm LBW; CHX – Chlorhexidine; OHI – Oral hygiene instruction

Optimal timing of treatment

The timing of periodontal intervention is a crucial factor which determines the success of periodontal treatment in reducing the adverse pregnancy outcomes. Most of the studies have discussed the optimal timing of periodontal intervention, which was between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation.[2,14,20,21,25]

Outcome measures considered

The outcome measures considered were the occurrence of PTB, LBW, and PTLBW. Twelve [2,5,6,7,8,14,15,20,21,22,24,25] of 19 studies showed the positive influence of periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcomes, and seven studies [3,4,16,17,18,19,23] reported no significant effect of periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcomes. Among the studies included in the present review, the occurrence of PTB [3,4,12,13,17,18,20,21,22,25,26] among the individuals who received periodontal therapy ranged from 0% to 53.5%, while in the control group, the range was 6.38%–72%. The occurrence of LBW [5,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,23] among the individuals treated for periodontal disease ranged from 0% to 36%, and in the control group, it varied from 1.15% to 53.9%. The incidence of PTLBW [2,6,7,15,18,21,23] among the test group ranged from 0% to 26.7%, whereas in the control group, it ranged from 4.15% to 79%. The odds of decreased occurrence of PTB, LBW, and PTLBW among the participants who received periodontal therapy when compared to the control group ranged 0.26–13.50, 1.008–4.3, and 1.05–5.49, consecutively.

DISCUSSION

Adverse pregnancy outcomes remain an important public health problem. Among the adverse pregnancy outcomes, PTB has been estimated as the cause for 28% of neonatal deaths.[31] The other adverse pregnancy outcomes are LBW, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes. The proven risk factors for the adverse pregnancy outcomes were young and advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, previous PTB, short cervix, low educational status, and fetal genotype.[1] Periodontal disease among pregnant women poses a considerable risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Researchers have suggested that translocation of periodontal pathogens to the fetal placental unit or the release of inflammatory mediators by the periodontal pathogens, which spreads through hematogenous route, affects the fetus. Numerous epidemiological studies evaluating the relationship between maternal periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes have reported conflicting results.

Consistent evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analysis indicates that pregnant women with periodontal disease are at increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[32,33,34] A meta-analysis concluded that pregnant women with periodontal disease have a 2.8-fold increased risk of PTB.[32] Hence, periodontal care should be given to pregnant mothers to prevent the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The mechanism of how periodontal treatment could reduce the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes is uncertain. The possible explanation might be the treatment for periodontal disease reduces the oral bacterial load thereby minimizing the risk of bacteremia and seeding of the fetal placental unit with pathogens which cause infection and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Another possible mechanism might be the reduction in oral bacterial load would reduce the production of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and prostaglandins associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.[22,35]

The effectiveness of periodontal therapy in reducing the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes may vary according to the study location and population characteristics. Studies done in USA [3,7,16,17] Australia [19] did not report the significant difference in the occurrence of PTB, LBW, and PTLBW, whereas studies done in Chile, Brazil, India, and Hungary [6,14,15,16,21] showed significant difference among them. The disparity maybe attributed to the sharing of similar characteristics with reference to age, gender, and exposure of risk factors of PTB among homogeneous population.

Among the studies included in this review, single center trials with a defined population [6,7,14,15,21,22] provided positive influence of periodontal treatment when compared to multicenter trials with a larger population [3,16,17] which showed negative results. The inconsistency of the study results can be attributed to the differences in the study population and providing patient care in case of multicenter trials.

Timing of periodontal intervention is a crucial factor which determines the efficacy of reducing signs and symptoms of periodontal disease and associated inflammatory response thereby its impact on reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes. Most of the studies discussed the optimal timing of treatment to be between 28 and 32 weeks.[2,14,20,21,25] While in some studies, periodontal intervention was carried out before 24 or 28th week,[3,7,8,23] and in a study done by Jeffcoat et al.,[7] the treatment was given before 35th week of gestation. Majority of large clinical trials did not show positive influence of periodontal therapy on adverse pregnancy outcomes when treatment was given in the second trimester.[3,16,17] The underlying mechanism being the intervention provided too late because by the time periodontal bacteria would have reached the fetoplacental unit and have initiated the process of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[36] Hence, if the adverse pregnancy outcomes could be linked to the presence of periodontal pathogens and inflammatory mediators, the correct timing of treatment could be before pregnancy or in the early stages of pregnancy.

The criteria used for defining the periodontal disease also differed among the studies considered for the review. Four studies [7,14,17,22] used CAL as the only criteria to define periodontal disease, whereas other studies [3,5,6,21] used a combination of probing depth, CAL, and bleeding on probing. Hence, standardized criteria should be used for defining periodontal disease to assess the influence of periodontal therapy on the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes without any disparity among the study results.

Most of the studies included in this review assessed the influence of periodontal treatment on PTB and LBW and only a few studies reported stillbirth as one of the primary outcomes.[3,19] Most of the studies reporting the success of periodontal therapy in this review considered mild to moderate cases of periodontitis because in severe cases, there is systemic dissemination of microorganisms and the infection does not completely resolve.[11,37,38] Hence, the study results cannot be generalized to individuals with severe periodontal disease.

Among the studies included in the review, the treatment and control groups were comparable with reference to the periodontal characteristics and exposure of risk factors. In majority of the studies, the treatment group received full-mouth scaling, root planing with oral hygiene instructions and followed by maintenance till delivery.[3,14] Few studies reported the use of chlorhexidine rinse as an adjunct to scaling and root planing [2,7,8,21] with significant results for control of periodontal disease. Among the control groups, only periodontal examination was done before delivery in some studies.[3,6,21] While in few studies, control groups received periodontal treatment after delivery.[2,14] Both the groups were followed until delivery for the assessment of birth outcomes.

Studies with high risk or unclear risk of bias [2,5,6,7,8,14,15,20,21,22,24,25] supported the beneficial influence of periodontal treatment in contrary to studies with low-risk of bias.[3,4,16,17,18,19,23] Hence, the influence of periodontal treatment on adverse pregnancy outcomes is uncertain, and further studies without the risk of bias evaluating the influence of periodontal treatment on adverse pregnancy outcomes should be conducted.

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis revealed a reduction in the occurrence of PTB with periodontal treatment in the population with the high-risk of the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[11,39] However, in case of moderate risk of occurrence of events, the results were not statistically significant.[11,37,38] Polyzos et al. in his meta-analysis found that periodontal disease during pregnancy had no significant effect on the reduction of PTB rate (odds ration [OR] – 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.95–1.40)[40] supported by meta-analysis performed by Chambrone et al. and Fogacci et al.[12,41]

In contrast to the above findings, George et al. in his meta-analysis found that periodontal treatment during pregnancy significantly reduces PTB (OR = 0.65, CI: 0.45–0.93).[39] In the recent systematic review, da Silva et al, concluded that intra-pregnancy non-surgical periodontal therapy decrease the level of inflammatory biomarkers from GCF and serum blood but it did not reduce the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[42] The differences reported in the study findings can be explained by the variation in strategies applied and the trials included for meta-analysis.

The strength of this systematic review is pertained to the inclusion of RCTs of varied methodological quality. The probable limitations of this systematic review could be the search for the relevant studies pertaining to three databases only, and the studies in the English language only were included. With best available evidence, it is sufficient to state that scaling and root planing alone is not effective in reducing the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Hence, this review highlights the need of further multicentered RCTs to be conducted with strict protocol, clearly defined criteria for the periodontal disease, and intervention during the early stages of pregnancy or preconception to assess the influence of periodontal therapy on adverse pregnancy outcomes.

CONCLUSION

The present systematic review concluded that nonsurgical periodontal therapy during pregnancy is safe, but it does not completely reduce the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Since nonsurgical periodontal therapy shows significant reduction in the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes among high-risk patients, it can be included as a part of antenatal care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my reviewers, colleagues, and staff of C.S.I College of Dental Sciences and Research for their kind support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Villar J, Carroli G, Wojdyla D, Abalos E, Giordano D, Ba'aqeel H, et al. Preeclampsia, gestational hypertension and intrauterine growth restriction, related or independent conditions? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:921–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gazolla CM, Ribeiro A, Moysés MR, Oliveira LA, Pereira LJ, Sallum AW. Evaluation of the incidence of preterm low birth weight in patients undergoing periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2007;78:842–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michalowicz BS, Hodges JS, DiAngelis AJ, Lupo VR, Novak MJ, Ferguson JE, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1885–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirie M, Linden G, Irwin C. Intrapregnancy non-surgical periodontal treatment and pregnancy outcome: A randomized controlled trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:1391–400. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy BV, Tanneeru S, Chava VK. The effect of phase-I periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcome in chronic periodontitis patients. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:29–32. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.829029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radnai M, Pál A, Novák T, Urbán E, Eller J, Gorzó I. Benefits of periodontal therapy when preterm birth threatens. J Dent Res. 2009;88:280–4. doi: 10.1177/0022034508330229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Hodgkins PM, et al. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: Results of a pilot intervention study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadatmansouri S, Sedighpoor N, Aghaloo M. Effects of periodontal treatment phase I on birth term and birth weight. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2006;24:23–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.22831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Task Force on Periodontal Treatment of Pregnant Women, American Academy of Periodontology. American Academy of Periodontology statement regarding periodontal management of the pregnant patient. J Periodontol. 2004;75:495. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanz M, Kornman K. working group 3 of the joint EFP/AAP workshop. Periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Consensus report of the joint EFP/AAP workshop on periodontitis and systemic diseases. J Periodontol. 2013;84(Suppl 4):S164–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah M, Muley A, Muley P. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy during gestation period on adverse pregnancy outcome: A systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1691–5. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.799662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambrone L, Pannuti CM, Guglielmetti MR, Chambrone LA. Evidence grade associating periodontitis with preterm birth and/or low birth weight: II: A systematic review of randomized trials evaluating the effects of periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:902–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Chichester; UK: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarannum F, Faizuddin M. Effect of periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcome in women affected by periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2095–103. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J. Periodontal therapy may reduce the risk of preterm low birth weight in women with periodontal disease: A randomized controlled trial. J Periodontol. 2002;73:911–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.8.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Jared HL, Mauriello SM, Mendoza LC, Couper DJ, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy on rate of preterm delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:551–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b1341f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macones GA, Parry S, Nelson DB, Strauss JF, Ludmir J, Cohen AW, et al. Treatment of localized periodontal disease in pregnancy does not reduce the occurrence of preterm birth: Results from the periodontal infections and prematurity study (PIPS) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:147.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weidlich P, Moreira CH, Fiorini T, Musskopf ML, da Rocha JM, Oppermann ML, et al. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy and strict plaque control on preterm/low birth weight: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0679-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newnham JP, Newnham IA, Ball CM, Wright M, Pennell CE, Swain J, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1239–48. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c15b40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khairnar MS, Pawar BR, Marawar PP, Khairnar DM. Estimation of changes in C-reactive protein level and pregnancy outcome after nonsurgical supportive periodontal therapy in women affected with periodontitis in a rural set up of India. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:S5–11. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.152930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López NJ, Da Silva I, Ipinza J, Gutiérrez J. Periodontal therapy reduces the rate of preterm low birth weight in women with pregnancy-associated gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2005;76(Suppl 11S):2144–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Offenbacher S, Lin D, Strauss R, McKaig R, Irving J, Barros SP, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy during pregnancy on periodontal status, biologic parameters, and pregnancy outcomes: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2011–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliveira AM, de Oliveira PA, Cota LO, Magalhães CS, Moreira AN, Costa FO. Periodontal therapy and risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15:609–15. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sant'Ana AC, Campos MR, Passanezi SC, Rezende ML, Greghi SL, Passanezi E. Periodontal treatment during pregnancy decreases the rate of adverse pregnancy outcome: A controlled clinical trial. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:130–6. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penova-Veselinovic B, Keelan JA, Wang CA, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. Changes in inflammatory mediators in gingival crevicular fluid following periodontal disease treatment in pregnancy: Relationship to adverse pregnancy outcome. J Reprod Immunol. 2015;112:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michalowicz BS, Novak MJ, Hodges JS, DiAngelis A, Buchanan W, Papapanou PN, et al. Serum inflammatory mediators in pregnancy: Changes after periodontal treatment and association with pregnancy outcomes. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1731–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novak MJ, Novak KF, Hodges JS, Kirakodu S, Govindaswami M, Diangelis A, et al. Periodontal bacterial profiles in pregnant women: Response to treatment and associations with birth outcomes in the obstetrics and periodontal therapy (OPT) study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1870–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert DA, Begg MD, Andrews HF, Williams SZ, Ward A, Conicella ML, et al. An examination of periodontal treatment, dental care, and pregnancy outcomes in an insured population in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:151–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell-Lewis D, Engebretson SP, Chen J, Lamster IB, Papapanou PN. Periodontal infections and pre-term birth: Early findings from a cohort of young minority women in New York. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:34–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeffcoat M, Parry S, Sammel M, Clothier B, Catlin A, Macones G. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: Successful periodontal therapy reduces the risk of preterm birth. BJOG. 2011;118:250–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891, 900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vergnes JN, Sixou M. Preterm low birth weight and maternal periodontal status: A meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:135.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daalderop LA, Wieland BV, Tomsin K, Reyes L, Kramer BW, Vanterpool SF, et al. Periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes: Overview of systematic reviews. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2018;3:10–27. doi: 10.1177/2380084417731097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komine-Aizawa S, Aizawa S, Hayakawa S. Periodontal diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:5–12. doi: 10.1111/jog.13782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shub A, Swain JR, Newnham JP. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:521–8. doi: 10.1080/14767050600797749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwendicke F, Karimbux N, Allareddy V, Gluud C. Periodontal treatment for preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes: A meta- and trial sequential analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim AJ, Lo AJ, Pullin DA, Thornton-Johnson DS, Karimbux NY. Scaling and root planing treatment for periodontitis to reduce preterm birth and low birth weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1508–19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.George A, Shamim S, Johnson M, Ajwani S, Bhole S, Blinkhorn A, et al. Periodontal treatment during pregnancy and birth outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9:122–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polyzos NP, Polyzos IP, Zavos A, Valachis A, Mauri D, Papanikolaou EG, et al. Obstetric outcomes after treatment of periodontal disease during pregnancy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c7017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fogacci MF, Vettore MV, Leão AT. The effect of periodontal therapy on preterm low birth weight: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:153–65. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdebc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.da Silva HE, Stefani CM, de Santos Melo N, de Almeida de Lima A, Rösing CK, Porporatti AL, et al. Effect of intra-pregnancy nonsurgical periodontal therapy on inflammatory biomarkers and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2017;6:197. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0587-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]