Abstract

Background:

The use of preprocedural mouth rinse is one of the recommended ways to reduce aerosol contamination during ultrasonic scaling. Different agents have been tried as preprocedural mouth rinse. Chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine significantly reduce the viable microbial content of aerosol when used as a preprocedural rinse. Studies have shown that aloe vera (AV) mouthwash is equally effective as chlorhexidine in reducing plaque and gingivitis. There is no published literature on the role of AV as a preprocedural mouth rinse. Hence, this study compared the effect of 94.5% AV to 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX) and 1% povidone-iodine (PVP-I) as preprocedural mouth rinses in reducing the aerosol contamination by ultrasonic scaling.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty subjects were divided into three groups based on the preprocedural rinse use (0.2% CHX, 1% PVP-I, and 94.5% AV). Ultrasonic scaling was done for 20 min in the same closed operatory for all the subjects after keeping blood agar plates open at two standardized locations. Colony forming units (CFUs) on blood agar plates were counted, and predominant bacteria were identified after incubation at 37°C for 48 h.

Results:

There was statistically significant difference in the CFU counts between CHX group and PVP-I group and between AV group and PVP-I group. There was no difference between CHX group and AV group at both the locations.

Conclusion:

94.5% AV as a preprocedural rinse is better than 1% PVP-I and comparable to 0.2% CHX in reducing CFU count.

Key words: Aerosol contamination, aloe vera, chlorhexidine, povidone iodine, preprocedural rinse

INTRODUCTION

The production of contaminated aerosol and splatter is one of the major concerns in the dental environment. Even though a multitude of dental procedures can generate a contaminated aerosol, the most intense aerosol and splatter ejection occurs during the use of an ultrasonic scaler and a high-speed handpiece. Different methods are used to intervene aerosol contamination including usage of personal protective equipment, high-efficiency particulate air room filters, ultraviolet treatment of ventilation system, use of high-volume evacuator and preprocedural rinsing with an antiseptic mouthwash.[1] Preprocedural rinsing is highly effective in reducing microorganisms in aerosol and numerous agents have been tried to this end.[2,3]

Chlorhexidine, the most commonly used anti-plaque mouth rinse and local delivery agent, significantly reduces the viable microbial content of aerosol when used as a preprocedural rinse.[4,5,6] Povidone-iodine (PVP), apart from its use as subgingival irrigant and coolant for ultrasonic scaling is also used as preprocedural mouth rinse.[7,8,9] Aloe barbadensis Miller (Aloe vera [AV]), a succulent plant belonging to Liliaceae family is well known for its moisturizing, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal properties.[10] AV, also known by a number of names such as “the wand of heaven,” “heaven's blessing,” and “the silent healer” is a promising herb with its various clinical applications in medicine and dentistry.[11] It has shown its potential as an anti-plaque agent and as an agent for local drug delivery.[12,13]

According to published evidence, AV has not been tried as a preprocedural mouth rinse yet. Being a natural product, it offers many advantages over chlorhexidine or PVP. This study compared the effect of 94.5% AV to 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX) and 1% PVP as preprocedural mouth rinse in reducing the aerosol contamination during ultrasonic scaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted from July 2018 to October 2018 and was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee and Review Board (IEC/M/12/2016/DCK). After obtaining verbal and written informed consent, patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the department of periodontics based on the following criteria: (a) above 18 years of age, (b) minimum of 20 permanent teeth, (c) plaque index (PI)[14] score between 2 and 3 and Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified (OHI-S)[15] score indicating poor or fair oral hygiene (1.3–6.0), (d) Four or more sites with probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥4 mm, and (e) systemically healthy individuals. Patients with definite contraindication for the use of ultrasonic scaling device, history of systemic or topical antibiotics use within the last 3 months, history of oral prophylaxis or mouth wash use within the past 3 months, with five or more carious lesions requiring an immediate restorative treatment, pregnant women, and current smokers were excluded from the study.

The sample size was 60, taking the mean and standard deviation of number of colony forming units (CFUs) from a previous similar study.[9] OHI-S, PI, and PPD were recorded for all subjects at baseline. They were divided into three groups (20 patients each) based on the type of preprocedural mouth rinse received as follows:

Group A (CHX): 0.2% chlorhexidine (CHX) (Rexidin®, Indoco Remedies Ltd., Aurangabad)

Group B (PVP-I): 1% PVP-I (Betadine®, Win-Medicare Pvt Ltd, New Delhi-PVP solution IP 10% W/V diluted to 1% using distilled water)

Group C (AV): 94.5% AV (AV juice with fibre and orange flavour®, Patanjali Ayurved Ltd, Haridwar).

Sheep blood agar plates (Biomerieux India Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai) were used to collect the aerosol produced. They were placed at two standardized locations-one at the patient's chest area and the other at operator's chest area. The average distance from the patient's mouth to agar plates was twelve inches. Ultrasonic scaling was done in the same closed operatory for all subjects as the first case of a day. Only one patient was treated a day. Before the procedure, all the surfaces were cleaned and disinfected with 70% isopropyl alcohol. Personal protective equipment were used for the operator as well as subjects. Distilled water was used as coolant for scaling; it was changed for every case. Furthermore, the water line was flushed at the start of each day for 1 min.

Preprocedural mouth rinse was given for 1 min to all subjects 10 min before the procedure. After keeping the agar plates open at prementioned sites, ultrasonic scaling was done using piezoelectric scaler for 20 min. Power setting, frequency, and water flow were standardized for all the cases as per manufacturer's recommendation. Then, the plates were closed, sealed, labeled, and immediately transferred to the department of microbiology for incubation at 37° for 48 h. The number of CFUs on blood agar plates was counted using colony counter (Labtronics microprocessor colony counter) and predominant bacteria were identified by the same experienced microbiologist for every sample. Bacterial identification was done based on colony morphology, hemolysis, Gram's staining and by biochemical reaction (Catalase test).

RESULTS

Statistical analysis of the collected data was done using SPSS 16 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL. USA). Intergroup comparison of the number of CFUs at both the locations was carried out using ANOVA. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. Intragroup comparison between the number of CFUs at two locations was done using independent t-test.

Of the total 60 participants, 30 were male and 30 female (age ranged from 18 to 55 years, mean age 37.42 ± 10.3). Clinical parameters-PI, OHI-S, and PPD were comparable at baseline [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics between three groups

| Parameter | Mean±SD | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHX group (n=20) | PVP-I group (n=20) | AV group (n=20) | ||

| PI | 2.31±0.23 | 2.43±0.22 | 2.40±0.21 | 0.248 |

| OHI-S | 3.80±0.97 | 3.87±1.03 | 3.88±1.01 | 0.962 |

| PPD | 2.74±0.25 | 2.75±0.30 | 2.55±0.30 | 0.063 |

One-way ANOVA. *Significant P<0.05. n – Sample size; CHX – Chlorhexidine; PVP-I – Povidone iodine; AV – Aloe vera; SD – Standard deviation; PI – Plaque index; OHI-S – Oral hygiene index-simplified; PPD – Probing pocket depth; P – Probability

The lowest number of mean CFUs was found in the chlorhexidine group, followed by AV group and highest in the PVP group in both the locations. The mean difference in the number of CFUs between CHX group and PVP-I group and between PVP-I group and AV group was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05), whereas between CHX group and AV group, it was not significant at both the locations [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of the number of colony forming units between three groups at operator’s chest area

| Location | Mean (95% CI) | P | Post hoc comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHX group (n=20) | PVP-I group (n=20) | AV group (n=20) | Group | Mean difference | SE | P | ||

| Opera-tor’s chest area | 25.25 (23.34-27.16) | 81.95 (78.87-85.03) | 27.85 (25.03-30.67) | 0.001* | CHX-PVP-I | 56.70 | 1.79 | 0.001* |

| CHX-AV | 2.60 | 1.79 | 0.456 | |||||

| PVP-I-AV | 54.10 | 1.79 | 0.001* | |||||

One-way ANOVA, post hoc Bonferroni correction, *Significant P<0.05. n – Sample size; CHX – Chlorhexidine; PVP-I – Povidone iodine; AV – Aloe vera; CI – Confidence interval; SE – Standard error; P – Probability

Table 3.

Comparison of the number of colony forming units between three groups at patient’s chest area

| Location | Mean (95% CI) | P | Post hoc comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHX group (n=20) | PVP-I group (n=20) | AV group (n=20) | Group | Mean difference | SE | P | ||

| Patient’s chest area | 37.15 (34.62-39.68) | 93.75 (90.41-97.09) | 40.50 (37.53-43.47) | 0.001* | CHX- PVP-I | 56.60 | 2.004 | 0.001* |

| CHX- AV | 3.35 | 2.004 | 0.300 | |||||

| PVP-I AV | 53.25 | 2.004 | 0.001* | |||||

One-way ANOVA, post hoc Bonferroni correction, *Significant P<0.05. n – Sample size; CHX – Chlorhexidine; PVP-I – Povidone iodine; AV – Aloe vera; CI – Confidence interval; SE – Standard error; P – Probability

Within each group, the mean difference between the number of CFUs at two locations was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05), with a higher mean number of CFUs at patient's chest area [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison between the number of colony forming units at two locations among the three groups

| Group | Mean difference | SE of difference | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHX | 11.90 | 1.51 | 8.84-14.97 | 0.001* |

| PVP-I | 11.80 | 2.17 | 7.40-16.19 | 0.001* |

| AV | 12.65 | 1.96 | 8.69-16.60 | 0.001* |

Independent t-test,*Significant P<0.05. CHX – Chlorhexidine; PVP-I – Povidone iodine; AV – Aloe vera; CI – Confidence interval; SE – Standard error; P – Probability

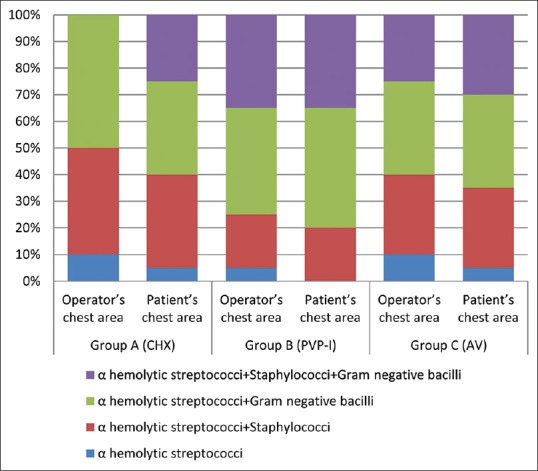

The predominant bacteria identified from the samples were Alpha-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and Gram-negative bacilli. The proportion of different bacteria identified from two locations in three groups is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The proportion of different bacteria identified from the culture among the three groups

DISCUSSION

Bioaerosols in dental operatory may contain many pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and fungi. As the production of aerosol and splatter cannot be evaded, it is important to adopt methods to intervene aerosol contamination. Preprocedural rinsing with an antiseptic mouth wash is one of the recommended ways.[16] Chlorhexidine and PVP significantly reduce the viable microbial content of aerosol when used as a preprocedural rinse.[3,9] Studies have shown that AV mouthwash is equally effective as chlorhexidine in reducing plaque and gingivitis.[12,17,18] To the extent of our knowledge, there is no published literature on the role of AV as a preprocedural mouth rinse. Hence, the present study compares the effect of 0.2% CHX, 1% PVP, and 94.5% AV as preprocedural mouth rinses in reducing the aerosol contamination by ultrasonic scaling.

There was a statistically significant difference between the three groups in the number of CFUs formed on blood agar plates at both locations [Tables 2 and 3]. As the patients in the three groups had similar oral hygiene and periodontal parameters (PI, OHI-S, and PPD) at baseline [Table 1], this difference in the number of CFUs can be attributed to the mouth rinse used.

The lowest number of mean CFUs was seen in the chlorhexidine group, followed by AV group and highest in the PVP group in both the locations. This may be due to the excellent broad-spectrum antimicrobial property and unique property of substantivity of chlorhexidine.[19] Literature is replete with studies that show the effectiveness of chlorhexidine as preprocedural rinse.[4,5,6,20]

Mean difference in the number of CFUs between CHX group and PVP-I group was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). However, randomized controlled trial by Kaur et al.[9] showed similar effects of 1% PVP-I and 0.2% CHX in reducing aerobic and anaerobic CFUs, but blood agar plates for sample collection were positioned at different locations, the operator's mask, patient's chest and a distance of 9 feet from patient's mouth.

Preceding studies have already shown that the antiplaque property of AV is comparable to chlorhexidine.[12,17,18] In the present study, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of CFUs between AV group and CHX group. However, the CFU count in AV group was lesser compared to PVP-I, which was statistically significant [Tables 2 and 3]. This suggests that AV as preprocedural rinse is better than PVP-I and is comparable to CHX in reducing the CFU count.

The above-mentioned findings can be explained by the significant anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial properties of AV. AV inhibit the inflammatory process by the reduction of leukocyte adhesion and proinflammatory cytokines.[21] It also inhibits the cyclooxygenase pathway and reduces prostaglandin E2 production, which plays an important role in inflammation.[10] Anthraquinones, an active compound in AV is structural analog of tetracycline, and it inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by blocking the ribosomal A site.[10] Pyrocatechol, a hydroxylated phenol in AV is toxic to microorganisms.[22]

A higher number of mean CFUs was observed in the patient's chest area as compared to operator's chest area. Mean difference between the number of CFUs at two locations was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) in all the three groups [Table 4]. Similar finding was also reported by Santos et al.[6] and Gupta et al.[23]

Bacterial identification of the predominant species was done from the same samples on both locations. Bacteria identified were Alpha-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and Gram-negative bacilli. Sawhney et al.[24] identified mixed group of microorganisms predominantly streptococci, staphylococci, pseudomonas, and aerobic spore-forming bacilli from aerosol. There are also studies employing advanced techniques for bacterial identification. Afzha et al.[25] utilized 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing to identify Streptococcus mutans and Staphylococcus aureus from contact lenses of the dentist after scaling and root planing using ultrasonic scalers. Feres et al.[26] recognized high proportions of bacteria belonging to purple, yellow, orange, and green complexes from splatter produced during ultrasonic scaling by means of checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization.

This is the first attempt to evaluate the effect of AV as a preprocedural mouth rinse, and this novelty is the highlight of the study. The lack of randomization in patient allocation and not employing specialized culture techniques for bacterial identification are limitations to this study. Inability to maintain a completely sterile clinical environment, lack of fumigation of operatory also needs mentioning in this regard.

AV being an herbal product is economical and devoid of the side effects that chlorhexidine is associated with including staining, burning sensation, and alteration of taste perception. Furthermore, chlorhexidine and PVP on long-term use may result in bacterial resistance. According to the findings of the present study, AV was comparable to CHX in terms of its ability to reduce the CFUs in aerosol when employed as a preprocedural rinse in the nonsurgical management of patients with periodontitis. However, further randomized controlled clinical trials in various centers using large samples are needed to prove this effect.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of the study, the following conclusions can be drawn: All the three rinses tested could reduce the aerosol load, 94.5% AV as a preprocedural rinse is comparable to 0.2% chlorhexidine and better than 1% PVP. It certainly warrants further randomized controlled clinical trials for a definitive conclusion.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Authors are thankful to Dr. Mary Shimi. S, Assistant professor, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Govt. Dental College, Kottayam for assistance in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: A brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:429–37. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine DH, Mendieta C, Barnett ML, Furgang D, Meyers R, Olshan A, et al. Efficacy of preprocedural rinsing with an antiseptic in reducing viable bacteria in dental aerosols. J Periodontol. 1992;63:821–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.10.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shetty SK, Sharath K, Shenoy S, Sreekumar C, Shetty RN, Biju T, et al. Compare the effcacy of two commercially available mouthrinses in reducing viable bacterial count in dental aerosol produced during ultrasonic scaling when used as a preprocedural rinse. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2013;14:848–51. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logothetis DD, Martinez-Welles JM. Reducing bacterial aerosol contamination with a chlorhexidine gluconate pre-rinse. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1634–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veksler AE, Kayrouz GA, Newman MG. Reduction of salivary bacteria by pre-procedural rinses with chlorhexidine 0.12% J Periodontol. 1991;62:649–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.11.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos IR, Moreira AC, Costa MG, Barbosa Md Castellucci e. Effect of 0.12% chlorhexidine in reducing microorganisms found in aerosol used for dental prophylaxis of patients submitted to fixed orthodontic treatment. Dental Press J Orthod. 2014;19:95–101. doi: 10.1590/2176-9451.19.3.095-101.oar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoang T, Jorgensen MG, Keim RG, Pattison AM, Slots J. Povidone-iodine as a periodontal pocket disinfectant. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:311–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.do Vale HF, Casarin RC, Taiete T, Bovi Ambrosano GM, Ruiz KG, Nociti FH, Jr, et al. Full-mouth ultrasonic debridement associated with povidone iodine rinsing in GAgP treatment: A randomised clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:141–50. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1471-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaur R, Singh I, Vandana KL, Desai R. Effect of chlorhexidine, povidone iodine, and ozone on microorganisms in dental aerosols: Randomized double-blind clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:160–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.135910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radha MH, Laxmipriya NP. Evaluation of biological properties and clinical effectiveness of aloe vera: A systematic review. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangaiyarkarasi SP, Manigandan T, Elumalai M, Cholan PK, Kaur RP. Benefits of aloe vera in dentistry. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S255–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.155943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhina S, Singh A, Menon I, Singh R, Sharma A, Aggarwal V, et al. A randomized clinical study for comparative evaluation of aloe vera and 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash efficacy on de-novo plaque formation. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6:251–5. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.183109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pradeep AR, Garg V, Raju A, Singh P. Adjunctive local delivery of aloe vera gel in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis: A Randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2016;87:268–74. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. i. prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrel SK, Barnes JB, Rivera-Hidalgo F. Aerosol and splatter contamination from the operative site during ultrasonic scaling. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1241–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vangipuram S, Jha A, Bhashyam M. Comparative efficacy of aloe vera mouthwash and chlorhexidine on periodontal health: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8:e442–e447. doi: 10.4317/jced.53033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta RK, Gupta D, Bhaskar DJ, Yadav A, Obaid K, Mishra S, et al. Preliminary antiplaque efficacy of aloe vera mouthwash on 4 day plaque re-growth model: Randomized control trial. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24:139–44. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v24i2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Addy M. Chlorhexidine compared with other locally delivered antimicrobials. A short review. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:957–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy S, Prasad MG, Kaul S, Satish K, Kakarala S, Bhowmik N, et al. Efficacy of 0.2% tempered chlorhexidine as a pre-procedural mouth rinse: A clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:213–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.99264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duansak D, Somboonwong J, Patumraj S. Effects of aloe vera on leukocyte adhesion and TNF-alpha and IL-6 levels in burn wounded rats. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2003;29:239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowan MM. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:564–82. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta G, Mitra D, Ashok KP, Gupta A, Soni S, Ahmed S, et al. Efficacy of preprocedural mouth rinsing in reducing aerosol contamination produced by ultrasonic scaler: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2014;85:562–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.120616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawhney A, Venugopal S, Babu GR, Garg A, Mathew M, Yadav M, et al. Aerosols how dangerous they are in clinical practice. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:ZC52–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12038.5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afzha R, Chatterjee A, Subbaiah SK, Pradeep AR. Microbial contamination of contact lenses after scaling and root planing using ultrasonic scalers with and without protective eyewear: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016;20:273–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.182599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feres M, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M, Stewart B, de Vizio W. The effectiveness of a preprocedural mouthrinse containing cetylpyridinium chloride in reducing bacteria in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:415–22. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]