Abstract

Purpose:

Periodic MV/KV radiographs taken during volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) for hypofractionated treatment provide guidance in intrafractional motion management. The choice of imaging frequency and timing are key components in delivering the desired dose while reducing associated overhead such as imaging dose, preparation, and processing time. In this project the authors propose a paradigm with imaging timing and frequency based on the spatial and temporal dose patterns of the treatment plan.

Methods:

A number of control points are used in treatment planning to model VMAT delivery. For each control point, the sensitivity of individual target or organ‐at‐risk dose to motion can be calculated as the summation of dose degradations given the organ displacements along a number of possible motion directions. Instead of acquiring radiographs at uniform time intervals, MV/KV image pairs are acquired indexed to motion sensitivity. Five prostate patients treated via hypofractionated VMAT are included in this study. Intrafractional prostate motion traces from the database of an electromagnetic tracking system are used to retrospectively simulate the VMAT delivery and motion management. During VMAT delivery simulation patient position is corrected based on the radiographic findings via couch movement if target deviation violates a patient‐specific 3D threshold. The violation rate calculated as the percentage of traces failing the clinical dose objectives after motion correction is used to evaluate the efficacy of this approach.

Results:

Imaging indexed to a 10 s equitime interval and correcting patient position accordingly reduces the violation rate to 19.5% with intervention from 44.5% without intervention. Imaging indexed to the motion sensitivity further reduces the violation rate to 12.1% with the same number of images. To achieve the same 5% violation rate, the imaging incidence can be reduced by 40% by imaging indexed to motion sensitivity instead of time.

Conclusions:

The simulation results suggest that image scheduling according to the characteristics of the treatment plan can improve the efficiency of intrafractional motion management. Using such a technique, the accuracy of delivered dose during image‐guided hypofractionated VMAT treatment can be improved.

Keywords: Dose‐volume analysis; Digital radiography; Dosimetry/exposure assessment; Therapeutic applications, including brachytherapy

Keywords: biological organs, diagnostic radiography, dosimetry, motion compensation, radiation therapy

Keywords: volumetric modulated arc therapy, radiation treatment planning, radiofrequency tracking, intrafractional motion management, prostate radiotherapy

Keywords: Radiation therapy, Analysis of motion

Keywords: Medical imaging, Dosimetry, Multileaf collimators, Digital image processing, Radiation treatment, Medical treatment planning, Databases, Medical image quality, Therapeutics, Radiography

I. INTRODUCTION

Periodic MV/KV radiographs taken during fixed gantry intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) or volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) can be utilized to resolve the 3D trajectory of implanted fiducial markers and subsequently provide guidance during intrafractional motion management. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 The geometrical accuracy of the system, tested with programmable motion phantoms, was found to be on the order of 1 mm in all three spatial dimensions. 8 This paradigm is the best alternative to the use of implanted radiofrequency (RF) transponders (Calypso®, Varian Medical System, Palo Alto, CA) to monitor intrafractional motion, particularly for clinical sites other than prostate, or for patients who subsequently receive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The Calypso transponders cause null signals with radii around 1.5 cm and length around 4 cm and preclude the use of MR in post‐treatment assessment. 9 The major operational overheads involved with the MV/KV approach are the time associated with preparing, acquiring, and processing of MV/KV images. Imaging dose to the patient must also be considered and is intimately related to the frequency at which the patient position is monitored. Continuous KV‐imaging of the patient, especially in hypofractionated treatment which may take 5–20 min would yield a prohibitively high dose, and is therefore unacceptable. A more acceptable solution is to use the cine‐MV images that are acquired serendipitously during VMAT delivery to monitor the patient position, and only acquire KV images when the MV images predict an excursion beyond predefined action thresholds. 6 , 7 However, robust 3D motion estimation using such an approach requires that intraprostatic markers be visible in the MV portal throughout the entire MV delivery. Although quality plans that expose the markers during the entire delivery are produced for lung and pancreas using special treatment plan optimization software, 10 more investigations need to be done to extend this approach to prostate or to routine clinical operation.

Intrafractional imaging capabilities provided by the TrueBeam® linac (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) expand the horizon of integrating image acquisition into dose delivery. For example, a number of KV imaging control points (CPs) can be inserted into the treatment delivery for a MV‐scatter‐free KV‐CBCT acquisition. 11 Similarly, a series of dedicated MV/KV imaging CPs can be inserted into the delivery to provide preprogrammed MV/KV image acquisitions. The imaging frequency and timing of such a method would be a key component in the design of any imaging protocol, and has direct impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of any intrafractional motion management strategy which aims to deliver a desired radiation dose while reducing associated organ‐at‐risk (OAR) complications and operational overhead. Currently, intrafractional imaging frequency is usually chosen according to clinical experience, such as 20–60 s in Cyberknife (Accuray, Palo Alto, CA) treatment. 12 A more sophisticated selection is based on computer simulations that limit the geometric excursions to a certain range and statistical confidence, such as 40 s to ensure markers are within 2 mm of their original position 95% of time. 13 However, these selections lack dosimetric perspective and are rarely related to quantities such as target or OAR dose, which are more clinically relevant and desirable. In this project we propose a paradigm for a prototype MV/KV imaging protocol that selects image timing and frequency based on the spatial and temporal dose patterns of the treatment plan for hypofractionated radiation treatment of prostate cancer.

II. METHOD AND MATERIALS

II.A. Treatment planning study

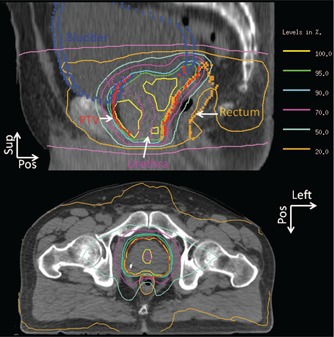

Treatment planning data from five patients treated under a hypofractionated prostate dose escalation protocol with a prescription dose of 42.5 Gy in five fractions were retrospectively studied with IRB approval. The size of the planning target volume (PTV) ranged from 92.1 cm3 to 139 cm3, with a median of 105.5 cm3. Clinical constraints for treatment planning include (1) 95% of the PTV receives at least 38.3 Gy, PTVD95 > 38.3 Gy, (2) maximum dose to urethra (UDmax) is less than 42.5 Gy, (3) dose received by 1 cm3 of the rectal wall (RWD1cc) is less than 38.5 Gy, and (4) dose received by 1 cm3 of the bladder wall (BWD1cc) is less than 42 Gy. Patients were treated using five‐field IMRT with full bladder, and Calypso monitoring, but single arc VMAT plans with 360° gantry rotation were retrospectively generated using our in‐house planning system 14 and subsequently used in this study. The monitor units (MU) of the five VMAT treatment plans ranged from 1711 to 2077, with a median of 1931. Delivery time is estimated to range from 236 to 286 s with a median of 260 s. Sagittal and transverse dose distributions from a typical plan are illustrated in Fig. 1. Note that the margin around the clinical target volume (CTV) is 3 mm between the prostate–rectum interface, and 5 mm elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Sagittal and transverse dose distributions from a typical hypofractionated prostate VMAT plan.

II.B. Sensitivity of dose to motion

In addition to the spatial dose distribution pattern a VMAT treatment plan also possesses a temporal dose deposition pattern. As the gantry rotates, dose deposition varies based on the dose rate and MLC shape of each CP. We postulate that the optimal distribution of images should not be simply and uniformly indexed to time, gantry angle, or MU, but to the sensitivity of the treatment plan to intrafractional patient motion throughout the treatment session. One way to quantify this is to study the sensitivity of individual target and OAR dose to motion. We define the directional sensitivity (Sen) of the ith CP, the kth region of interest (ROI), and the mth direction as

| (1) |

where N k is the number of points randomly placed inside the kth ROI using a density of 30–50 points/cm3 instead of a grid to save computer memory, 15 is the dose deposited to the jth point inside the kth ROI by the ith CP without any motion, is the dose calculated with a rigid ROI displacement of v m along the mth direction inside a static patient CT, MUi is the MU delivered by the ith CP, and N CP is the total number of CPs, H(x) is the step function that returns x for x > 0, and 0 otherwise, and sign(ROIk) returns −1 for target and 1 for OARs. Twenty six possible rigid 3D displacements of patient geometry along a combined direction of right (R), left (L), anterior (A), posterior (P), superior (S), and inferior (I), including R00, L00, 0A0, 0P0, 00S, 00I, RA0, RP0, LA0, LP0, R0S, R0I, L0S, L0I, 0AS, 0AI, 0PS, 0PI, RAS, RAI, LAS, LAI, RPS, RPI, LPS, and LPI were studied in the directional sensitivity calculation. The amplitude of v m is set to be 1 mm because only small amount of motion is allowed along certain directions, such as the interface between the rectal wall and the prostate, to ensure that no clinical dose limits to OAR are violated. Typical patterns of the directional sensitivity of dose to motion are illustrated for rectum wall and bladder wall, in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b), respectively.

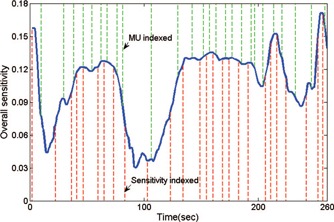

Figure 2.

Typical patterns of sensitivity of dose to motion. (a) Directional sensitivity of rectum wall. (b) Directional sensitivity of bladder wall. (c) Combined directional sensitivity [maximum of the 26 direction as described in Eq. (2)] of CTV, urethra, bladder wall, and rectal wall. (d) Overall plan sensitivity [maximum of different ROIs as described in Eq. (3)] and MU delivered by the treatment plan.

The overall sensitivity of a particular dose distribution to motion can be appreciated by evaluating the maximum directional sensitivity of a specific structure and control point over all directions, given by

| (2) |

Similarly, the maximum directional sensitivity overall structures at a specific CP is

| (3) |

Maximum function was selected over a weighted sum to avoid the complexity of choosing weighting factors for different ROIs. The maximum directional sensitivities of the rectal wall, bladder wall, CTV, and urethra to motion are illustrated in Fig. 2(c) along with the CP weight or MU delivered throughout the VMAT arc consisting of 177 CPs. The maximum CP sensitivity to motion is shown in Fig. 2(d). In this example, MU peaks around the gantry 90° and 270°, while the sensitivity peaks at the gantry 180°, reflecting the importance of rectal wall protection. Although motion sensitivity and MU are highly correlated, other factors including the spatial relationship and proximity between the MLC aperture and various OARs are equally important.

II.C. Imaging indexed to sensitivity

The purpose of MV/KV imaging is to identify excursions from the planned position so that they may then be corrected via couch movement to ensure treatment quality. Moreover, an optimal imaging scenario is comprised of imaging points triggered by the motion sensitivity. Treatment intervals with higher sensitivity include more frequent imaging. To design such a scenario, we first integrate the motion sensitivity over the entire delivery as A. Next, the treatment course is divided into N I intervals of equal sensitivity integration, where N I is the number of desired imaging. Within the rth interval, the time point with the highest sensitivity, t max, is identified and the image acquisition is then scheduled at time t r = t max − t p, where t p is conservatively set to 2 s to ensure that the patient is in the correct position via the potential image based correction when the motion sensitivity is the highest. To prevent excessively long or short periods between images, we also impose two rules limiting the shortest time between successive image acquisitions to no less than 2 s and the longest time to no more than 2T/N I, where T is the entire delivery time. Any violations of the two rules result in a corresponding shift of the scheduled imaging. A typical time series for MV/KV imaging can be seen in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Plot of overall treatment plan sensitivity to intrafraction motion vs elapsed time. Imaging acquisitions indexed to sensitivity and MU are plotted in lower and upper dotted lines, respectively.

II.D. MV/KV image acquisition

Currently, preprogrammed MV/KV acquisition such as that described here can only be achieved via a custom XML script executed in the Developer mode on the platform of TrueBeam. A VMAT treatment DICOM RTPlan file is first converted to XML via an in‐house program. Additional “MV/KV imaging” CPs are then inserted between the “treatment” CPs at points determined from the motion sensitivity analysis. The MLC aperture of each MV imaging CP is set to be the same as the shortened preceding treatment CP unless alteration is required to fully visualize all fiducials. The changes of the MLC positions were determined on the corresponding digitally reconstructed radiograph (DRR) on which MLC aperture was projected, and kept to a minimum so as to not significantly alter the dosimetric characteristics of the plan. The beam‐on time of one MV imaging CP can be set as low as 0.4 MU, which is the minimum to produce quality MV projections for the purpose of visualization and registration, and is deducted from the MU of the preceding treatment CP. For imaging CP that require no MLC aperture modification to visualize the fiducials, there is no associated overhead in terms of either delivery time or patient dose. If however, the MLC shape must be changed, the additional time associated with forming the desired aperture could reach 1–2 s if the fiducials are originally blocked. In this scenario, if necessary, the gantry will slow down to allow the MLC to catch up. In addition, there could be dosimetric consequences although we believe these will be relatively minor and would not need to be considered during optimization assuming 20–30 MV/KV image acquisitions per hypofractionated treatment and a total imaging‐related dose of up to 8–12 MU, which is around 0.5% of treatment MU. KV acquisition is independent of MV acquisition, and is specified just after the MV acquisition to avoid MV scatter. KV acquisition can be switched on and off as programmed instead of working in a continuous mode, therefore no excessive KV dose is delivered to the patient. The dose from a standard pelvis kV‐CBCT with 660 projections is measured to be around 3–7 cGy at the isocenter. 16 For a programmed acquisition of 20–30 kV projections, dose is estimated to be less than 0.4 cGy per fraction and 2 cGy in the entire 5 fraction treatment. MV/KV image pairs can be exported via a vendor supplied workstation attached to the image acquisition system (iTool Capture) for real‐time analysis, or saved for offline review after treatment.

II.E. Motion management strategy

We have previously reported a methodology to prospectively calculate a patient specific action window for electromagnetic‐tracking (Calypso®) guided VMAT delivery. 17 Intra‐fraction motion traces from the Calypso database were linked to a VMAT delivery. Cumulative dose was calculated for the simulated delivery assuming rigid transformation, and checked to determine whether dose constraints in the clinical protocol were violated due to the motion. Action thresholds along the RL, AP, and SI directions were derived as the largest possible box that contains no dose limit violations. This patient specific methodology was tested against other traces from the database and found to be capable of robust detection of dose violations with a higher sensitivity and specificity than using generic action thresholds such as 2 mm in all the directions. Therefore, it is used in this study to determine the action threshold. The tightest action threshold is found to be in the anterior direction with a value of around 0 to 1.1 mm as listed in Table I.

Table I.

Patient specific action thresholds for five patients.

| Patient | Superior (mm) | Inferior (mm) | Left (mm) | Right (mm) | Anterior (mm) | Posterior (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 1 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 3.8 |

| 3 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 3.8 |

| 4 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 0 | 3.8 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 3.8 |

During a VMAT delivery with MV/KV imaging, motion traces can be resolved by rigidly registering the paired 2D projections to the corresponding DRRs from the plan CT. The time spent in the registration process is around 500 ms with in‐house software. A future release of the TrueBeam software will allow couch adjustments during treatment. If the movement calculated from the registration exceeds the action threshold, patient position could be corrected via a couch shift either during a beam hold or simultaneously with the treatment. Shifting couch during beam‐on is only allowed when the intended shift is small, <5 mm, so that patient would not feel and react to the couch movement. Since the maximal motion correction allowed during beam‐on is only 5 mm, the reaction time for the couch correction would be less than ∼500 ms. Therefore, the overall system reaction time for the delivery system is estimated to be about 1 s. If the detected motion is larger than 5 mm, which happens 1% of the time in our motion trace database, a beam hold can be issued first. If the patient motion is verified by an extra ad hoc MV/KV imaging session, couch can be corrected accordingly during beam hold.

II.F. Simulation design

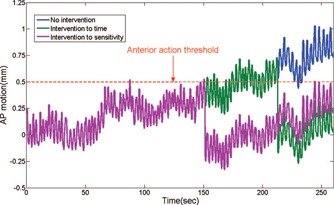

The purpose of this project is to evaluate the feasibility of the prototype motion management strategy described above and provide insight in the selection of appropriate imaging parameters. A computer simulation utilizing 114 traces, each at least 5 min long, in the Calypso database 17 is applied to assess the potential clinical impact of the motion management strategy. At the time of each simulated “MV/KV image,” patient position is corrected back to the planned position if the motion at the time of image exceeds any of the action thresholds with a system lag time of 1 s. Cumulative dose is recalculated given the corrected traces and OAR and target doses are re‐evaluated. The dose violation rate is calculated as the percentage of traces that, despite position correction, still led to OAR or target dose limit violations. Three sets of experiments, using imaging indexed to motion sensitivity, evenly spaced time intervals, and evenly spaced MU, are compared to investigate the advantages of motion sensitivity‐based imaging. The image acquisition frequency is once every 10 s in the equitime arm as suggested in our previous couch correction study. 18 The same number of image acquisitions was prescribed for the motion sensitivity and MU arm, with variable temporal spacing as shown in Fig. 3. An example of an anterior–posterior trace corrected using either the motion sensitive or equitime method is illustrated in Fig. 4. Note that the patient‐specific action thresholds for the anterior and posterior directions are 0.5 mm and 3.8 mm, respectively. Furthermore, the patient with the median delivery time is chosen to investigate the relationship between the dose violation rate and the selection of image number and timing.

Figure 4.

Plot of Calypso traces corrected by the couch shift strategy based on images taken indexed to time and sensitivity.

To evaluate the impact of the motion management strategy on the hypofractionated treatment, the dose violation rate of a single fraction delivery (VR1) needs to be converted to the dose violation rate of a five fraction delivery (VR5). The number of possible combinations of randomly picking five traces from the Calypso database with a total of N traces is Calculating accumulative dose for all these combinations and deriving the violation rate is computational prohibitive. One simple way to estimate VR5 is to assume that (1) interfractional organ motion and setup variation are corrected with either a pretreatment cone beam CT or an orthogonal image pair, and (2) dose limits of the cumulative five fractions are violated only when violations exist in the majority (≥3) of the fractions. Under these assumptions VR5 is determined by

| (4) |

Although this estimation based on simple majority does not compute the real accumulative dose, it could still serve as a theoretical indicator and facilitate decision making.

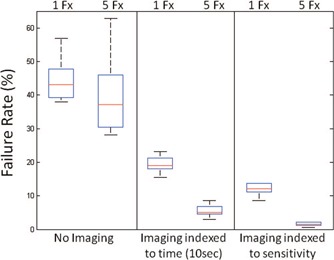

III. RESULTS

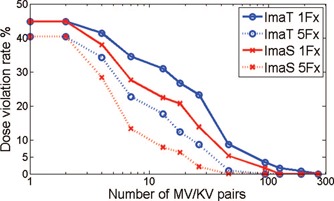

As illustrated in Fig. 5, VR1 ranges from 37.9% to 56.9%, and averages 44.5% when no motion correction is applied via imaging for the five patients tested in the study. Imaging every 10 s and correcting accordingly improves VR1 to an average of 19.5% with a range from 15.5% to 23.2%. Applying the same number of image acquisitions, but with imaging indexed to sensitivity, further reduces VR1 to an average of 12.1%, with a range from 8.6% to 13.8%. For a five fraction delivery VR5 is estimated via Eq. (4) to be 39.9%, 5.6%, and 1.5% for no imaging, imaging indexed to time, and imaging indexed to sensitivity, respectively. MLC apertures needed to be adjusted in 38% of the scheduled MV images to fully visualize all the three implanted fiducials. The required MLC movement ranged from 0.5 to 2.5 cm, and averaged 1.6 cm per alternation. The MLC modification caused an extra 7 s in treatment delivery and had less than 0.3% impact on the delivered dose. Not all motion outliers are caught by the MV/KV approach due to its much lower imaging frequency compared to the 100 ms intervals of Calypso. The residual geometric excursions outside the action thresholds occurring in the corrected traces are 6% in the motion sensitivity arm, and slightly higher than 5.3% in the equitime interval arm. The amplitude of the residual error averaged 0.13 cm with a maximum of 1.5 cm, in both arms. The number of corrections per trace in the sensitivity arm is 2.0, slightly lower compared to 2.2 in the time arm, which is probably due to the longer imaging idling time, up to 20 s in the sensitivity arm vs a fixed 10 s in the other. Image acquisition indexed to motion sensitivity is more effective than that to equitime interval because corrections are made at more crucial moments.

Figure 5.

Comparison of dose objective violation rate between imaging indexed to time and sensitivity. In this boxplot the center line indicates the median, and the edge of the box shows the 25%–75% percentiles.

A simplified alternative to imaging indexed to sensitivity is to MU, which is a significant contributor to the sensitivity calculation. For imaging indexed to MU with an imaging rate equivalent to 1 per 10 s, the average VR1 and VR5 for the five patients studied are 16.1% and 3.4%, respectively. The less effectiveness of imaging indexed to MU compared to sensitivity is due to the suboptimal image timing, especially at the end of the treatment, during which there is a higher probability of a larger prostate motion. 19

The relationship between the dose violation rate and the number and timing of MV/KV pairs taken for the patient with the median 260 s delivery time is illustrated in Fig. 6 for the motion sensitivity and equitime arms, assuming single and five fractions. If only one or two image pairs are acquired, no matter how they are arranged, VR1 remains at 44.8%, the same as without imaging. As number of imaging increases, violation rate starts to drop rapidly due to motion management. Imaging indexed to motion sensitivity provides the most drop of VR1 over the equitime arm in the range of taking 20–40 images per 260 s treatment, corresponding to a uniform imaging intervals between 6 and 13 s. The improvement of reduction in dose violation rate is in the range of 5%–10%. There is also impact in the improvement of efficiency. For example, to achieve the same 5% VR5 for a five‐fraction treatment, imaging indexed to equitime interval requires an imaging rate of 1 per 8 s (acquiring 33 MV/KV pairs) and 2.2 interventions per trace; while imaging indexed to motion sensitivity requires only 19 MV/KV pairs, a 42% reduction, and only 1.6 interventions per trace, a 28% reduction. To pursue a zero VR5, the sensitivity arm requires 43 MV/KV pairs, in contrast to 93 pairs necessary in the equitime arm. The extra MV imaging dose would be 17.2 MU in the sensitivity arm vs 37.2 MU in the equitime arm, which is 1.9% of the total MU delivered in the treatment plan. The MLC aperture adjustment in the equitime arm would require 25 s, compared to 12 s in the sensitivity arm. The 13 s reduction is 5% of the total beam‐on time.

Figure 6.

Relationship between the number of image acquisitions and the reduction of dose violation rate.

The entire procedure of determining imaging sequence and evaluating its efficacy took 5–6 h running on a 2.33 GHz Intel Xeon quadcore computer with 3 GB RAM. The unsupervised motion sensitivity and dose accumulation calculation using all the traces in the Calypso database account for 99% of the time spent. We envision utilizing this program during the night before a treatment plan is pushed to the delivery system to minimize the impact to the clinical workflow.

IV. DISCUSSION

In this investigation we demonstrate that an effective and efficient imaging strategy should consider the spatial and temporal pattern of the treatment plan. As illustrated in Fig. 2, a few directional components dominate the overall motion sensitivity at a specific time. In the case of rectal wall and posterior irradiation at gantry 180°, detecting motion along the left and right directions is the most important. As a consequence MV imaging that monitors LR and SI is more crucial than KV imaging that monitors AP and SI. As gantry rotates to 90°, the dominant directional components are anterior and anterior‐superior. Again MV imaging that monitors AP and SI at 90° gantry is more critical than KV imaging that monitors LR and SI. Similar observations exist in the bladder wall analysis. Imaging from the direction of the beam portal is always essential to detect the motion that causes the most serious dose degradations. Therefore, a MV/KV imaging strategy is superior to a pure KV‐fluoroscopy 20 , 21 or KV‐sequential stereo 22 , 23 based protocol. However, KV imaging should not be excluded since its quality and resolution is superior to MV, and it contributes to robustly reconstructing the true 3D trajectory. Different imaging techniques have their own intrinsic characteristics. The best way to design an imaging strategy is to find the best match between imaging and the treatment plan delivery.

Our simulation suggests that imaging indexed to sensitivity and with an acquisition frequency equivalent to one pair per 10 s is sufficient to reduce the dose violation rate to a 5% level. This is consistent to the findings in the Calypso study done by Malinowski et al., 24 which suggests that manually gating treatment for 11 s is the most desirable option to maintain a 3 mm accuracy if realistic repositioning overhead is taken into account in the motion management strategy. The imaging rate determined in this study is more frequent than the one per 20–60 s imaging interval in the Cyberknife literature. 12 , 13 We believe it is a result of the escalated prescription dose and the challenge to meet clinical constraints posed in this study.

The efficiency benefit brought by imaging indexed to sensitivity compared to equitime is moderate when images are acquired equivalent to 1 per 10 s to achieve a 5% violation rate in a five fraction treatment. However, if we adopt a more stringent criterion that allows no violations, the advantages of imaging indexed to sensitivity become more obvious in the reduction of imaging dose, modifications to the MLC apertures in the treatment plan, and interruptions during the delivery. Furthermore, the extra 1.9% imaging dose introduced by imaging indexed to equitime in the example described in Sec. III would more likely trigger a plan reoptimization, which is a major setback in the workflow. The quality of the plan derived through reoptimization is not guaranteed to be as good as the original plan since it would be very challenging to expose all fiducials to the MLC aperture at roughly every third gantry angle to accommodate the 93 MV/KV pairs in addition to the demanding clinical OAR sparing protocol. Treating patients with high radiation dose in a single fraction, for the benefit of patient's convenience and potential better pathological response, such as paraspinal tumors are treated in our clinic, 25 could be adopted in the foreseeable future. The efficiency savings of an intelligent motion management strategy in a single fraction protocol will be more significant because a zero violation rate is highly desired given no opportunities to repair the patient's treatment after delivery.

Due to the tight constraints imposed on rectal wall sparing, the action thresholds along some directions are below 1 mm, which is at the reported geometry accuracy of the MV/KV imaging system. To improve the accuracy of the MV/KV imaging system, an automatic algorithm that utilizes the prior shape knowledge of the fiducials to match the fiducials in the MV/KV pair with the DRR is implemented in our institution. Test on phantom shows that the uncertainty of the algorithm is ∼0.2 mm. 26 Future patient studies would benefit from the application of this algorithm. Another method to reduce the uncertainty of the imaging system is to deploy an ad hoc verification MV/KV pair immediately after the action threshold is violated. The repeated measurement would improve the robustness of the system.

Innovations in treatment planning or motion correction techniques would require more advanced and sophisticated strategies. For example, instead of utilizing the margin expansion approach in conventional radiation therapy, novel treatment planning techniques such as 4D inverse planning link the optimization of dose delivery at a specific moment to the phase of the target motion, thereby reducing OAR toxicity. 27 , 28 A potential motion management strategy for such an approach is to derive a time or target motion phase specific action threshold based on the analysis of sensitivity to motion. Faster and more accurate deformable registration can improve the accuracy of dose accumulation and sensitivity estimation. 29 , 30 , 31 The sensitivity analysis could inform us that the severe deformations of the target or OAR make the treatment unrepairable and online replanning is required. 32 , 33 , 34 The motion sensitivity analysis can be parallelized since dose calculations with respect to each CP and motion direction are separable. Calculation time can be significantly shortened with cluster computation. More time savings can be achieved by only evaluating the efficacy with a small subset of the traces. Therefore, the MV/KV imaging schedule could be potentially updated during delivery given the accumulated dose. As we implement more novel technologies into the clinic and accumulate more clinical experience we will have a more comprehensive analysis of the system and further improve the integration of the treatment planning process with the delivery process to maximize the gain of intrafractional motion management.

V. CONCLUSION

The simulation results suggest that image scheduling according to the characteristics of the treatment plan can improve the efficiency of intrafractional motion management. Using such a technique, the accuracy of delivered dose during image‐guided hypofractionated VMAT treatment can be improved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Michelle Svatos from Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA for her help and discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cho B., Poulsen P. R., Sloutsky A., Sawant A., and Keall P. J., “First demonstration of combined kV/MV image‐guided real‐time dynamic multileaf‐collimator target tracking,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 74(3), 859–867 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu W., Wiersma R. D., Mao W., Luxton G., and Xing L., “Real‐time 3D internal marker tracking during arc radiotherapy by the use of combined MV‐kV imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53(24), 7197–7213 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/24/013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mao W., Riaz N., Lee L., Wiersma R., and Xing L., “A fiducial detection algorithm for real‐time image guided IMRT based on simultaneous MV and kV imaging,” Med. Phys. 35(8), 3554–3564 (2008). 10.1118/1.2953563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mao W., Hsu A., Riaz N., Lee L., Wiersma R., Luxton G., King C., Xing L., and Solberg T., “Image‐guided radiotherapy in near real time with intensity‐modulated radiotherapy megavoltage treatment beam imaging,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 75(2), 603–610 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu W., Wiersma R. D., and Xing L., “Optimized hybrid megavoltage‐kilovoltage imaging protocol for volumetric prostate arc therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78(2), 595–604 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu W., Luxton G., and Xing L., “A failure detection strategy for intrafraction prostate motion monitoring with on‐board imagers for fixed‐gantry IMRT,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78(3), 904–911 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu W., Qian J., Hancock S. L., Xing L., and Luxton G., “Clinical development of a failure detection‐based online repositioning strategy for prostate IMRT–experiments, simulation, and dosimetry study,” Med. Phys. 37, 5287–5297 (2010). 10.1118/1.3488887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiersma R. D., Mao W., and Xing L., “Combined kV and MV imaging for real‐time tracking of implanted fiducial markers,” Med Phys. 35, 1191–1198 (2008). 10.1118/1.2842072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu X., Bourland J. D., Yuan Y., Zhuang T., O'Daniel J., Thongphiew D., Wu Q. J., Das S. K., Yoo S., and Yin Y. Y., “Tradeoffs of integrating real‐time tracking into IGRT for prostate cancer treatment,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54(17), N393–N401 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/17/N03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma Y., Lee L., Keshet O., Keall P., and Xing L., “Four‐dimensional inverse treatment planning with inclusion of implanted fiducials in IMRT segmented fields,” Med. Phys. 36(6), 2215–2221 (2009). 10.1118/1.3121425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ling C., Zhang P., Etmektzoglou T., Star‐Lack J., Sun M., Shapiro E., and Hunt M., “Acquisition of MV‐scatter‐free kilovoltage CBCT images during RapidArc™ or VMAT,” Radiother. Oncol. 100(1), 145–149 (2011). 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hossain S., Xia P., Chuang C., Verhey L., Gottschalk A. R., Mu G., and Ma L., “Simulated real time image guided intrafraction tracking‐delivery for hypofractionated prostate IMRT,” Med Phys. 35(9), 4041–4048 (2008). 10.1118/1.2968333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xie Y., Djajaputra D., King C. R., Hossain S., Ma L., and Xing L., “Intrafractional motion of the prostate during hypofractionated radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 72(1), 236–246 (2008). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Niemierko A. and Goitein M., “Random sampling for evaluating treatment plans,” Med. Phys. 17(5), 753–762 (1990). 10.1118/1.596473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang P., Happersett L., and Mageras G., “Volumetric modulated arc therapy: Implementation and evaluation for prostate cancer cases,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 76(5), 1456–1462 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ding G. X. and Coffey C. W., “Radiation dose from kilovoltage cone beam computed tomography in an image‐guided radiotherapy procedure,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 73(2), 610–617 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang P., Mah D., Happersett L., Cox B., Hunt M., and Mageras G., “Determination of action thresholds for electromagnetic tracking system‐guided hypofractionated prostate radiotherapy using volumetric modulated arc therapy,” Med. Phys. 38(7), 4001–4008 (2011). 10.1118/1.3596776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McNamara J., Lovelock D., Yorke E., and Mageras G., “Proof of principle investigation of computer controlled couch adjustments for correcting drift in target position during radiotherapy,” Med. Phys. 37, 3184 (2010). 10.1118/1.3468389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghilezan M. J., Jaffray D. A., Siewerdsen J. H., Van Herk M., Shetty A., Sharpe M. B., Jafri S. Z., Vicini F. A., Matter R. C., Brabbins D. S., and Martinez A. A., “Prostate gland motion assessed with cine‐magnetic resonance imaging (cine‐MRI),” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 62(2), 406–417 (2005). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poulsen P. R., Cho B., Ruan D., Sawant A., and Keall P. J., “Dynamic multileaf collimator tracking of respiratory target motion based on a single kilovoltage imager during arc radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 77(2), 600–607 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adamson J. and Wu Q., “Prostate intrafraction motion assessed by simultaneous kilovoltage fluoroscopy at megavoltage delivery I: Clinical observations and pattern analysis,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78(5), 1563–1570 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mestrovic A., Nichol A., Clark B. G., and Otto K., “Integration of on‐line imaging, plan adaptation and radiation delivery: Proof of concept using digital tomosynthesis,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54(12), 3803–3819 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/12/013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cho B., Poulsen P. R., and Keall P. J., “Real‐time tumor tracking using sequential kV imaging combined with respiratory monitoring: A general framework applicable to commonly used IGRT systems,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55(12), 3299–3316 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/12/003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Malinowski K., Noel C., Roy M., Willoughby T., Djemi T., Jani S., Solberg T., Liu D., Levine L., and Parikh P. J., “Efficient use of continuous, real‐time prostate localization,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53(18), 4959–4970 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/18/007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamada J., Bilsky M. H., Lovelock M., Venkatraman E. S., Toner S., Johnson J., Zatcky J., Zelefsky M., and Fuks Z., “Image‐guided intensity‐modulated radiation therapy for spinal tumors,” Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 6(3), 207–211 (2006). 10.1007/s11910-006-0007-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Regmi R., Lovelock M., Hunt M., Zhang P., Pham H., Xiong J., Yorke E., Goodman K., and Mageras G., “Tracking implanted fiducials using Kilovoltage (kV) projection images: A feasibility study,” in Proceedings of the AAPM 2012 Annual Meeting Oral Presentation, Med. Phys. 39(6), 3903 (2012). 10.1118/1.4735931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma Y., Chang D., Keall P., Xie Y., Park J., Suh T., and Xing L., “Inverse planning for 4D modulated arc therapy,” Med. Phys. 37, 5627–5633 (2010). 10.1118/1.3497271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chin E. and Otto K., “Investigation of a novel algorithm for true 4D‐VMAT planning with comparison to tracked, gated and static delivery,” Med. Phys. 38(5), 2698–2707 (2011). 10.1118/1.3578608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao S., Zhang L., Wang H., de Crevoisier R., Kuban D. D., Mohan R., and Dong L., “A deformable image registration method to handle distended rectums in prostate cancer radiotherapy,” Med. Phys. 33(9), 3304–3312 (2006). 10.1118/1.2222077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brock K. K., Nichol A. M., Ménard C., Moseley J. L., Warde P. R., Catton C. N., and Jaffray D. A., “Accuracy and sensitivity of finite element model‐based deformable registration of the prostate,” Med. Phys. 35(9), 4019–4025 (2008). 10.1118/1.2965263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bender E. T. and Tomé W. A., “The utilization of consistency metrics for error analysis in deformable image registration,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54(18), 5561–5577 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/18/014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adamson J. and Wu Q., “Prostate intrafraction motion assessed by simultaneous kV fluoroscopy at MV delivery II: Adaptive strategies,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78(5), 1323–1330 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Men C., Jia X., and Jiang S. B., “GPU‐based ultra‐fast direct aperture optimization for online adaptive radiation therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55(15), 4309–4319 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/15/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li T., Thongphiew D., Zhu X., Lee W. R., Vujaskovic Z., Yin F. F., and Wu Q. J., “Adaptive prostate IGRT combining online re‐optimization and re‐positioning: A feasibility study,” Phys. Med. Biol. 56(5), 1243–1258 (2011). 10.1088/0031-9155/56/5/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]