Abstract

BACKGROUND

Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) is an extremely rare and highly invasive malignant tumor of the liver. To our knowledge, the imaging findings of sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma have been rarely reported; and radiological features of this tumor mimicking liver abscess have not yet been reported.

CASE SUMMARY

We present a case of SICC mimicking liver abscess. The patient, a 43-year-old male, complained of repeated upper right abdominal discomfort and intermittent distension over a period of one month. Radiology examination revealed a huge focal lesion in the right liver. The lesion was hypointense on computed tomography with honeycomb enhancement surrounded by enhanced peripheral areas. It showed a hypo-signal on non-contrast T1-weighted images and a hyper-signal on non-contrast T2-weighted images. Radiologists diagnosed the lesion as an atypical liver abscess. The patient underwent a hepatectomy. After surgery, he survived another 2.5 mo before passing away. A search of PubMed and Google revealed 43 non-repeated cases of SICC reported in 20 published studies. The following is a short review in order to improve the diagnostic and therapeutic skills in cases of SICC.

CONCLUSION

This report presents the clinical and radiological features of SICC and imaging features which showed hypovascularity and progressive enhancement. SICC can present as a multilocular cyst on radiological images and it is necessary to distinguish this lesion from an atypical abscess. Simple surgical treatment is not the best treatment option for this disease.

Keywords: Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Liver abscess, Radiological features, Case report

Core tip: Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) is an extremely rare and highly invasive malignant tumor of the liver. The radiological features of this lesion have been rarely reported and it is difficult to differentiate this tumor from a liver abscess. We present the clinical, radiological characteristics and treatment of a patient with SICC followed by a summary of relevant English literature regarding this condition, including a prognosis analysis of SICC.

INTRODUCTION

Sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma is a rare intrahepatic malignant tumor, accounting for 4.5% of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas[1]. Spindle-shaped and pleomorphic cells and adenoid structures are observed in sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma[1]. In the relevant literature, it is also known as cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatous changes[2]. The tumor pathogenesis has not been sufficiently clarified. The prognosis of sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma is worse than that of conventional cholangiocarcinoma[1]. Pathological diagnosis is the gold standard for diagnosing sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma. However, a preoperative biopsy can lead to intra-tumor bleeding and dissemination[2]. It is imperative to improve the preoperative diagnosis using imaging examination. To our knowledge, the imaging findings of sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma have rarely been reported, nor have its radiological features mimicking liver abscess. We report a patient with intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) and discuss the imaging and clinical features of this unusual disease through a careful review of the literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

The patient was a 43-year-old male suffering from repeated upper right abdominal discomfort and intermittent distension over a period of one month. There was no report of radiation of the pain to his shoulder and back.

History of present illness

There was neither a history nor symptoms of fever, yellowish eyes, weight loss, or vomiting.

History of past illness

He had a 25-year history of hepatitis B. He did not take any routine medication.

Personal and family history

His medical and family history did not reveal any history of serious or terminal illnesses or any other relevant information.

Physical examination upon admission

His temperature was 37°C, resting heart rate was 80 bpm, respiratory rate was 15 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg.

Laboratory examinations

The results of blood analysis were as follows: Red blood cells, 5.08 × 1012/L [normal range: (3.5-5.5) × 1012/L]; white blood cells, 7.7 × 109/L [normal range: (4-10) × 1012/L], and platelet count, 149 × 109/L [normal range: (80-300) × 109/L]. The results of liver function tests were as follows: Albumin, 39.3 g/L [normal range: (35.0-53.0) g/L]; globulin, 25.5 g/L [normal range: (17.0-33.5) g/L]; lactic dehydrogenase, 181.0 U/L [normal range: (109.0-245.0) U/L]. The results of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin were 4 mg/L [normal range: (0-8) mg/L] and 0.04 ng/mL [normal range: (0-0.5) ng/mL], respectively. Other measurements were as follows: Serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) 66.91 ng/mL (normal range < 10 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen 1.02 ng/mL (normal range < 5 ng/mL), serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 and CA 125 levels were 19.9 U/mL and 26.3 U/mL (normal range: < 35 U/mL), respectively.

Imaging examinations

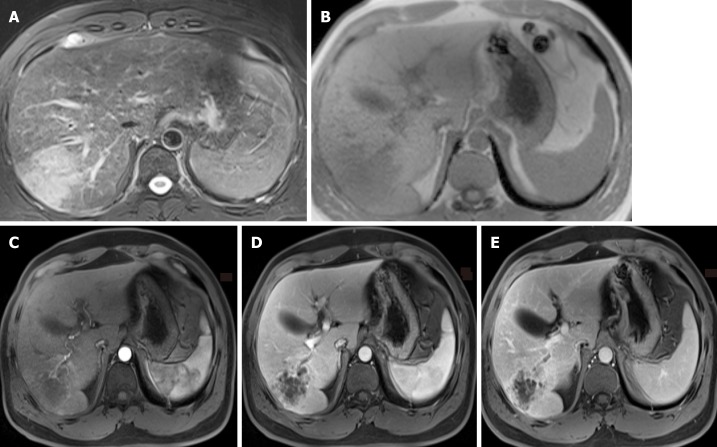

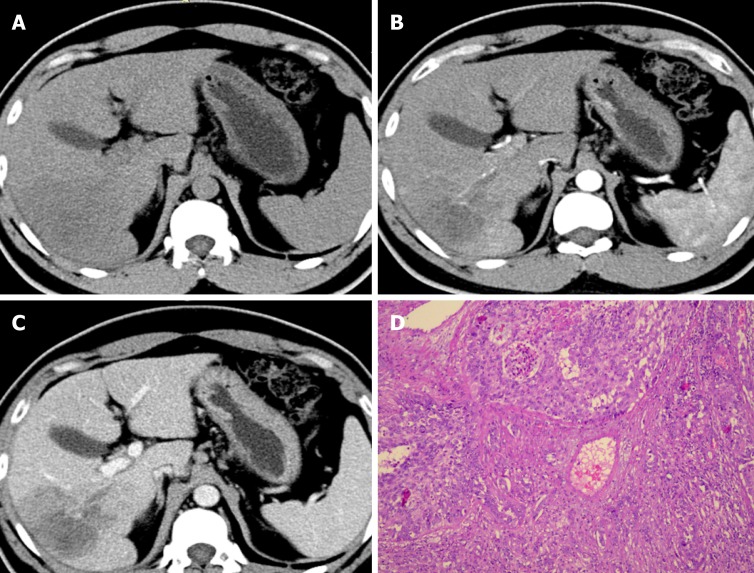

An abnormal mass of hypointensity on T1-weighted images (T1WI) and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images (T2WI) was observed in the right liver lobe (Figure 1). On post-contrast T1WI, honeycomb-like continuous enhancement, with slight transient hepatic parenchymal enhancement (THPE) around it, and adjacent proximal bile duct dilatation with enhancement of the wall were observed. In the arterial phase, blood vessels could be seen entering the lesion. Initially, a hepatic abscess could not be excluded. Further computed tomography (CT) examination (Figure 2) showed that the right lobe of the liver had a patchy low-density lesion of approximately 7.0 cm × 5.6 cm with heterogeneous enhancement. Mild dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct and enlarged lymph nodes of the retroperitoneal region were observed.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging results. A-B: There is an abnormal lesion occupying the right lobe of the liver, hyperintense on non-contrast T2 weighted images and hypointense on non-contrast T1 weighted images; C-E: A honeycomb-like structure and persistent enhancement with slight transient hepatic parenchymal enhancement around it and adjacent proximal bile duct dilatation with enhancement of the wall on contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images were observed.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography images and histopathologic findings (100 ×). A-C: The right lobe of the liver shows a patchy low-density shadow of approximately 7.0 cm × 5.6 cm with heterogeneous enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging; D: The cells are spindle to round in shape, with scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei, forming nests and microglandular structures.

The diagnosing physician considered it to be a malignant occupation; thus, surgical resection was performed. During the operation, no ascitic fluid was found in the abdominal cavity. The liver was reddish-brown and nodular hyperplasia of the liver could be seen. A mass in the right lobe of the liver was observed, which had a hard texture. In addition, no satellite lesions were found around this mass. The surgeon diagnosed it as liver cancer and performed radical hepatectomy and lympha-denectomy.

The gross cross-section examination revealed a yellowish-white mass. On microscopic examination, the tumor consisted of an adenocarcinoma component and a sarcomatous component, and the background liver showed nodular hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical examination of the mass revealed positive staining for CD34, CK19, and pancytokeratin AE1/AE3, and negative staining for CA19, hepatocytes, AFP, HMBE-1, G3, TG, TTF1, and CK5/6.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on the histological and immunohistochemical findings, the tumor was diagnosed as an intrahepatic less differentiated sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma.

TREATMENT

The patient underwent radical hepatectomy. After surgery, he was treated with anti-infection agents, rehydration, and symptomatic treatment.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The overall duration of follow-up was only 2.5 mo as the patient passed away.

DISCUSSION

Sarcomatous changes that occur in cholangiocarcinoma are considered rare and the World Health Organization[3] classification of tumors defines sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) as a cholangiocarcinoma with spindle cell areas resembling spindle cell sarcoma or fibrosarcoma or with features of malignant fibrous histiocytoma. At present, the specific pathological mechanism of cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatosis has not been clarified. Clinical manifestations as well as radiological imaging of this tumor are still limited.

An internet research was carried out using the search engines PubMed and Google with the keywords: “liver”, “sarcomatous”, “sarcomatoid”, “sarcomatosis” and “cholangiocarcinoma”. References of related literature were also reviewed to identify any other potentially relevant publications. After detailed search and analysis, 43 non-repeated cases of SICC were identified in 20 published studies[1,2,4-20].

The following tables (Tables 1-3) present a summary of the previous English-language literature with the addition of the present case. The clinical features of SICC were non-specific. Abdominal pain and fever were the most common complaints in patients. The age of the patients ranged from 37 to 87 years (median age, 61.5 years) with SICC being more commonly observed in men. This is consistent with the age and sex of the patient in the current study. Similar to typical cholangiocarcinoma, SICC usually occurs in the left lobe of the liver.

Table 1.

Summary of sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reported in English-language literature from 1992 to 2019

| Ref. | Case No. | Age/sex | Clinical symptom | Location | Size (cm) | Treatment | Outcome (mo) |

| Nakajima et al[1] | 1 | 84/F | Anorexia, jaundice, abdominal pain | Hepatic hilum | 3.5 | None | Died 3 |

| 2 | 45/F | Fever | Right lobe | 14.0 | Surgery | Died 4.5 | |

| 3 | 73/F | Abdominal mass | Left lobe | 7.0 | Chemotherapy | Died 5 | |

| 4 | 37/M | Abdominal discomfort, epigastralgia | Left lobe | 10.0 | None | Died 2.5 | |

| 5 | 64/M | Abdominal discomfort, nausea | Left lobe | 7.5 | TAE | Died 1 | |

| 6 | 52/M | Right hypochondralgia | Right lobe | 7.5 | TAE | Died 2 | |

| 7 | 69/M | Fever | Left lobe | 10.0 | Surgery | Well 36 | |

| Inoue et al[2] | 8 | 61/M | Abdominal pain, distention | Left lobe | 25.0 | Surgery | Died 1.1 |

| Haratake et al[4] | 9 | 59/M | Fever, icterus, abdominal mass | Hepatic hilar | NA | Supportive | Died 1 |

| Imazu et al[5] | 10 | 77/M | Liver tumor | Left lobe | 7.0 | Surgery | NA |

| Honda et al[6] | 11 | 61/F | Back pain | Right and Left lobe | NA | Supportive | Died 3.8 |

| Matsuo et al[7] | 12 | 77/F | Abdominal pain | Left lobe | 4.3 | Surgery | Died 5 |

| Itamoto et al[8] | 13 | 70/M | Fatigue, fever | Right lobe | 8.0 | Surgery | Well 9 |

| Kaibori et al[9] | 14 | 69/F | Fever, abdominal pain | Left lobe | 20.0 | Surgery | Died 3 |

| Gupta et al[10] | 15 | 50/M | Jaundice | Hepatic hilum | 2.0 | NA | NA |

| Lim et al[11] | 16 | 41/F | Palpable epigastric mass | Left lobe | 17.0 | Surgery | Alive 2 |

| Sato et al[12] | 17 | 87/M | Elevated ductal enzyme levels | Left lobe | 4.0 | Supportive | Died 3 |

| Malhotra et al[13] | 18 | 60/F | Abdominal pain, abdominal mass | Left lobe | 20.0 | Surgery and chemotherapy | Well 29 |

| Bilgin et al[14] | 19 | 48/M | Abdominal pain, fatigue | Left lobe | 13.0 | Surgery and chemotherapy | Alive 12 |

| Jung et al[15] | 20 | 59/M | Pain, dizziness, mild fever | Right lobe | 18.0 | Surgery and chemotherapy | Well 8 |

| Watanabe et al[16] | 21 | 62/M | Liver tumor, jaundice | Hepatic hilum | 4.5 | Surgery and chemotherapy | Died 11 |

| Kim et al[17] | 22 | 67/M | Abdominal pain | Left lobe | 6.0 | Surgery | Alive 6 |

| Shi et al[18] | 23 | 55/M | NA | Right lobe | NA | Surgery | Died 2 |

| 24 | 47/M | NA | Right lobe | NA | Surgery | Died 6 | |

| Zhang et al[19] | 25 | 63/M | Abdominal pain | Left lobe | NA | Surgery | Well 4 |

| Kim et al[20] | 26 | 45/M | Abdominal pain | NA | 7.5 | Chemotherapy | Died 1.6 |

| 27 | 67/M | Abdominal pain | NA | 2.5 | Chemotherapy | Died 4.9 | |

| 28 | 55/M | Abdominal pain, fever | NA | 6.5 | Chemotherapy | Died 4.3 | |

| 29 | 66/M | Abdominal pain, fever | NA | 10.0 | Supportive | Died 0.7 | |

| 30 | 56/M | Abdominal pain, fatigue | NA | 8.0 | Chemotherapy | Died 2.4 | |

| 31 | 66/M | Abdominal pain | NA | 7.5 | Chemotherapy | Died 4.2 | |

| 32 | 68/M | BWL, fatigue | NA | 6.0 | Supportive | Died 0.6 | |

| 33 | 55/M | Abdominal pain, fever | NA | 8.5 | Chemotherapy | Died 1 | |

| 34 | 49/M | Abdominal pain, fever | NA | 9.5 | Chemotherapy | F/U | |

| 35 | 65/M | Abdominal pain | NA | 9.5 | Supportive | Died 0.5 | |

| 36 | 61/M | Abdominal pain | NA | 5.0 | Viscum album | Alive 12.7 | |

| Tsou et al[21] | 37 | 77/F | Abdominal pain, palpable mass, BWL | Left lobe | 14.0 | None | Died 2 |

| 38 | 62/M | Abdominal pain, BWL | Right lobe | 3.0 | Unknown | F/U | |

| 39 | 59/M | Abdominal pain, palpable mass, BWL | Left lobe | 11.0 | None | Died 1 | |

| 40 | 63/M | Dyspnea, BWL | Right lobe | 14.0 | None | Died 0.3 | |

| 41 | 64/M | Back pain | Left lobe | 11.0 | Surgery | Died 2 | |

| 42 | 50/F | Abdominal pain | Right lobe | 4.5 | Surgery | Died 2 | |

| 43 | 69/F | Abdominal pain, fever | Left lobe | 2.5 | Surgery | Alive 48 | |

| Our case | 44 | 43/M | Abdominal discomfort | Right lobe | 7.0 | Surgery | Died 2.5 |

F: Female; M: Male; BWL: Body weight loss; TAE: Transarterial embolization; NA: Not available; F/U: Lost to follow-up.

Table 3.

Summary of radiological features of 44 patients

| Radiological features | Number | ||

| Location | Left lobe | 18/44 (40.9%) | |

| Right lobe | 10/44 (22.7%) | ||

| Hepatic hilum | 4/44 (9.0%) | ||

| Multiple | 1/44 (2.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 11/44 (25.0%) | ||

| Tumor size (cm)1 | 9.0 ± 5.2 | ||

| US | Hypoechoic | 6/23 (26.1%) | |

| Hyperechoic | 3/23 (13.0%) | ||

| Mixed-echoic | 10/23 (45.5%) | ||

| Unseen | 1/23 (4.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 3/23 (13.0%) | ||

| CT | Plain | Low density | 19/19 (100%) |

| Enhancement | Enhanced peripheral areas (progressive enhancement to the central region) | 22/23 (95.7%) | |

| (12/23) (52.2%) | |||

| Without enhancement | 1/23 (4.3%) | ||

| MRI | T1 WI | Iso/Low intensity | 6/8 (75.0%) |

| T2 WI | High intensity border | 1/8 (12.5%) | |

| High and low intensity | 5/8 (62.5%) | ||

| Unknown | 2/8 (25.0%) | ||

| Enhancement | Enhanced peripheral areas (progressive enhancement to the central region) | 2/8 (25.0%) | |

| (2/8) (25.0%) | |||

| Unknown | 6/8 (75.0%) | ||

| Angiography | Hypovascularity | 1/3 (33.3%) | |

| Unknown | 2/3 (66.7%) | ||

Values for tumor size are presented as means ± SD (n = 44). CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.s

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reported in the English-language reports and our case

| Clinical characteristics | Number | |

| Age (yr)1 | 60.8 ± 11.3, 61.5 | |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 33:11 (3:1) | |

| Clinical symptoms | ||

| Abdominal pain/discomfort | 26/44 (59.1%) | |

| Fever | 11/44 (25.0%) | |

| Abdominal mass | 6/44 (13.6%) | |

| Jaundice | 4/44 (9.0%) | |

| Digestive symptoms | 2/44 (4.5%) | |

| Fatigue | 4/44 (9.0%) | |

| Back pain | 2/44 (4.5%) | |

| Body weight loss | 4/44 (9.0%) | |

| Dizziness | 1/44 (2.3%) | |

| None | 2/44 (4.5%) | |

Values for age are presented as means ± SD (n = 44) and median.

Radiologic imaging of SICC is still limited. It usually shows a clear low or mixed echo mass on ultrasound[21]. CT examination revealed low density lesions, clear or unclear, and sometimes with intra-tumor hemorrhage[15]. Most lesions had enhanced peripheral areas in the arterial phase and gradually filled in the central region. In our case, on CT analysis, the lesion was seen as a patchy low-density mass with an unclear boundary. Heterogeneous enhancement was observed in peripheral areas, with no obvious enhancement in the inner necrosis area. In addition, there was slight THPE around the mass. As a result, it is difficult to distinguish SICC from an atypical liver abscess. It was reported that satellite foci may appear in SICC; and there is a certain relationship between satellite nodules and SICC[14]. In the case reported herein, no daughter nodules were found. On magnetic resonance imaging, the lesion had low signal on T1WI and high signal on T2WI. After enhancement, a honeycomb-like structure and persistent enhancement with slight THPE and adjacent proximal bile duct dilatation with enhancement of the wall were observed. In addition, blood vessels were observed entering the lesion, which was also considered a distinguishing feature. The SICC involved multiple cystic changes accompanied by fibrous septum and was inhomogeneous and hyperintense in the center on DWI mapping, which was similar to atypical liver abscess on DWI mapping[18]. Unfortunately, our patient had no evidence of diffusion restriction. Abdominal angiography showed that the tumor was supplied by the hepatic artery and was considered anemic[7], which was consistent with the results after enhancement.

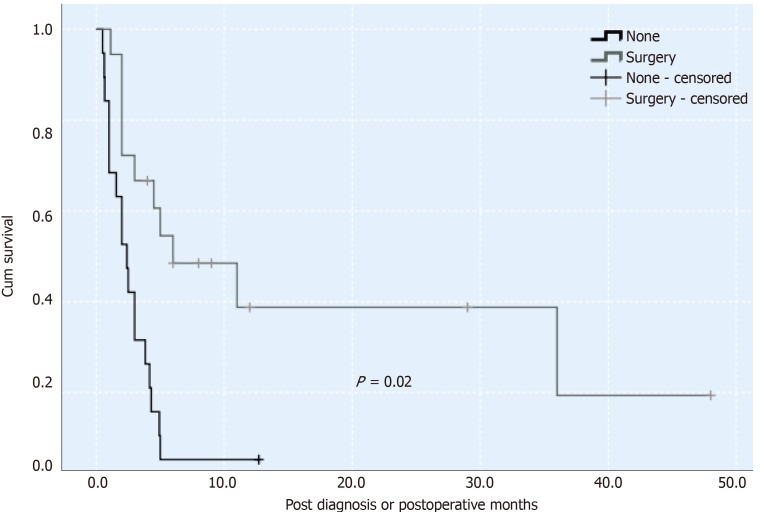

The degree of SICC malignancy is higher than that of traditional cholangiocarcinoma. The general prognosis for this malignancy is 3 mo[1]. It may be associated with an intrinsic sarcoma-like component, with high invasiveness. Most of these tumors are removed by surgery, and there is no unified comprehensive treatment for them. A previous study reported that surgery and postoperative treatment of a combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin adjuvant therapy can improve the prognosis of patients, and survival can be as long as 29 mo[13]. However, the effectiveness of chemotherapy remains unclear. According to the survival curve (Figure 3), using the Kaplan-Meier method, in 44 patients with SICC reported in the literature and our case, the survival rate of patients who underwent surgery was significantly higher than those without surgery. The present patient did not undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy after surgery, only supportive treatment. This was likely a contributing factor in his postoperative survival time of only 2.5 mo.

Figure 3.

Survival rates of operated sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and non-operative sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Survival rates of 44 cases of sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) calculated by Kaplan–Meier method [operated SICC (black solid line) and non-operative SICC (grey solid line)] are shown. The difference was estimated using the generalized log-rank method. P values of less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the clinical and radiological features of SICC are non-specific. The usual symptoms are abdominal pain and fever and the imaging features are hypo-vascularity and progressive enhancement. SICC can present as a multilocular cyst on radiological images and it is necessary to distinguish it from an atypical abscess. It is very difficult to diagnose SICC accurately prior to surgery. The last necessary pre-operative biopsy is used for identification. Pathological diagnosis is the gold standard for diagnosing SICC. We report a case of SICC mimicking liver abscess and previous reports were reviewed to increase our understanding of the clinical and imaging evidence of SICC in order to improve the preoperative diagnostic ability for radiologists as well as surgeons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to our foreign teacher, a Canadian, for his contribution to language polishing and thank the patients and their family members who agreed to publish this case.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: This report was approved by the ethics committee and the patients provided written informed consent.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 10, 2019

First decision: November 13, 2019

Article in press: November 30, 2019

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Anand A, Isik A, Ramia J, Rungsakulkij N, Valek V S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Qi LL

Contributor Information

Yan Wang, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China.

Jia-Lei Ming, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xing-Yu Ren, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China.

Lu Qiu, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China.

Li-Juan Zhou, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China.

Shu-Dong Yang, Department of Pathology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiang-Ming Fang, Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Wuxi People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi 214023, Jiangsu Province, China. xiangming_fang@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Nakajima T, Tajima Y, Sugano I, Nagao K, Kondo Y, Wada K. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatous change. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical evaluation of seven cases. Cancer. 1993;72:1872–1877. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930915)72:6<1872::aid-cncr2820720614>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue Y, Lefor AT, Yasuda Y. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatous changes. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:1–4. doi: 10.1159/000335883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed; p. 417. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haratake J, Yamada H, Horie A, Inokuma T. Giant cell tumor-like cholangiocarcinoma associated with systemic cholelithiasis. Cancer. 1992;69:2444–2448. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920515)69:10<2444::aid-cncr2820691010>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imazu H, Ochiai M, Funabiki T. Intrahepatic sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:677–682. doi: 10.1007/BF02367798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda M, Enjoji M, Sakai H, Yamamoto I, Tsuneyoshi M, Nawata H. Case report: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with rhabdoid transformation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:771–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuo S, Shinozaki T, Yamaguchi S, Takami Y, Obata S, Tsuda N, Kanematsu T. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with extensive sarcomatous change: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:560–563. doi: 10.1007/BF02482354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itamoto T, Asahara T, Katayama K, Momisako H, Dohi K, Shimamoto F. Double cancer - hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with a spindle-cell variant. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:422–426. doi: 10.1007/s005340050144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaibori M, Kawaguchi Y, Yokoigawa N, Yanagida H, Takai S, Kwon AH, Uemura Y, Kamiyama Y. Intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1097–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta K, Powari M, Dey P. Sarcomatous cholangiocarcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:168–169. doi: 10.1002/dc.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim BJ, Kim KS, Lim JS, Kim MJ, Park C, Park YN. Rhabdoid cholangiocarcinoma: a variant of cholangiocarcinoma with aggressive behavior. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:543–546. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato K, Murai H, Ueda Y, Katsuda S. Intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma of round cell variant: a case report and immunohistochemical studies. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:585–590. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra S, Wood J, Mansy T, Singh R, Zaitoun A, Madhusudan S. Intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma. J Oncol. 2010;2010:701476. doi: 10.1155/2010/701476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilgin M, Toprak H, Bilgin SS, Kondakci M, Balci C. CT and MRI findings of sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:447–451. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2012.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung GO, Park DE, Youn GJ. Huge subcapsular hematoma caused by intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2012;16:70–74. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2012.16.2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe G, Uchinami H, Yoshioka M, Nanjo H, Yamamoto Y. Prognosis analysis of sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma from a review of the literature. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19:490–496. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HM, Kim H, Park YN. Sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells associated with hepatolithiasis: A case report. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:309–313. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.21.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi D, Ma L, Zhao D, Chang J, Shao C, Qi S, Chen F, Li Y, Wang X, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Li H. Imaging and clinical features of primary hepatic sarcomatous carcinoma. Cancer Imaging. 2018;18:36. doi: 10.1186/s40644-018-0171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang N, Li Y, Zhao M, Chang X, Tian F, Qu Q, He X. Sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12549. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DK, Kim BR, Jeong JS, Baek YH. Analysis of intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma: Experience from 11 cases within 17 years. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:608–621. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i5.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsou YK, Wu RC, Hung CF, Lee CS. Intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma: clinical analysis of seven cases during a 15-year period. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]