Abstract

Physiological and growth responses of two Australian Echinochloa colona biotypes (glyphosate-resistant and susceptible, produced from a single population) to different concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) (ambient ~450 ppm and elevated ~750 ppm) and soil moisture (well-watered and water-stressed) were analyzed. Elevated CO2 and well-watered conditions resulted in E. colona plants with greater biomass, height and numbers of tillers and leaves in both biotypes; however, no significant response was observed for seed production or the amount of photosynthesis pigments with increasing CO2 at both soil moisture levels. In addition, water availability was more influential for growth than CO2 concentration. The mean shoot biomass of the susceptible biotype under elevated CO2 and well-watered conditions was significantly greater than the resistant biotype. Although the susceptible biotype showed more vegetative and reproductive growth than the resistant biotype, no significant difference was observed for seed production between the biotypes in the water-stressed condition. In a second experiment, different doses of glyphosate (0, 180, 360, 720 and 1440 g a.e ha−1) were applied to both biotypes grown at two soil moisture levels (well-watered and water-stressed). In the water-stressed condition, glyphosate efficacy was decreased in both biotypes. The resistant biotype in the well-watered condition had only 19% survival at 1440 g ha−1 glyphosate (double the recommended rate), but this value increased in the water-stressed condition by 62%. Our study suggests that future climate change can affect the physiological and growth processes of weeds and their responses to herbicides. Knowledge of their adapting behaviors will be critical to weed management strategies.

Subject terms: Plant ecology, Abiotic

Introduction

Climate components such as radiation, temperature and precipitation have a direct impact on the agriculture industry. Therefore, climate change could affect plant biophysiological processes and productivity1. An increase in the emission of greenhouse gasses (carbon dioxide-CO2, methane-CH4 and nitrous oxide-N2O4), aerosols, temperature and evaporation, as well as a decrease in precipitation will be important factors of future climate change2. These factors will influence other variables, such as different stresses (drought, salinity, etc), changes in pests’ life cycles and soils quality3–6.

The current atmospheric CO2 concentration, recorded at Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, is 411 ppm7. Some studies have quantified a difference of 80 ppm in the CO2 concentration between urban and suburban areas8,9. According to emission scenarios on climate change as reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), CO2 concentrations are predicted to be in the range between 600 to 1000 ppm at the end of the 21st century10.

Increased levels of CO2 in C4 weeds have less beneficial photosynthetic effects compared with C3 weeds because they already have a pathway for inhibiting photorespiration11. Different studies assessed that under current temperature conditions, elevated CO2 can increase aboveground biomass and productivity of some weeds through greater carbon availability and increases in photosynthesis4,12,13. However, increases in temperature, floods and drought can change the effect of elevated CO2 because plants respond to all environmental factors and one factor can influence the other factors14.

Some studies predicted a shift in the precipitation pattern and soil moisture deficiency15–20 For example, the amount of rainfall is expected to decrease in central Queensland, Australia, by 10–20% of the current rainfall by 207016 and an average decrease of 2–5% is expected in all areas of Australia except the far north of Queensland by 203021.

The change in the pattern of rainfall and temperature as a result of climate change can lead to the growth of C4 and thermophile weeds4,22. Some grass weeds, such as Echinochloa spp., Setaria spp., Digitaria spp., and Sorghum halepense, have expanded their distribution range because of climate change over past decades23. E. colona is highly sensitive to water stress24,25. Early stomata closing and reductions in CO2 assimilation and photosynthetic enzyme activities are the main responses of water deficit in plants26.

Plants have different pigments for absorbing light at different wavelengths, allowing a greater efficiency in light absorption in the photosynthetic process27. The number of photosynthetic pigments may change with environmental factors28–31. The effect of drought, CO2 concentration and temperature on different physiological processes in canola (Brassica napus) were studied and significant differences were reported between temperatures, CO2 concentrations and soil moistures for photosynthetic pigments content31.

Weeds are always among the problematic components in cropping systems. Therefore, understanding of weeds’ responses to climate change is essential for developing weed management strategies. Climate change can induce transformations and shifts in the weed flora and consequently changes their distribution and traits, making some of the opportunistic weeds invasive32. Response to climate change may vary, depending on the weed, region, latitude or soil33.

Echinochloa colona (L.) Link is a C4 annual summer grass native to Europe and India. It is a problematic weed in more than 60 countries and 35 crops34. In Australia, it has become problematic in summer fallows and crops such as maize (Zea mays L.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.)35,36. E. colona is an invasive weed with its vigorous growth traits and high seed production37. Each E. colona plant is capable of producing up to 42,000 seeds. Seeds can germinate at different ranges of soil temperature and moisture conditions38. The excessive use of glyphosate for E. colona control may exert an extreme selection pressure and lead to the evolution of resistant biotypes39. Glyphosate-resistant biotypes of E. colona have been reported in many cropping systems of Australia35.

Several studies showed that glyphosate efficacy is affected by soil moisture40,41. Although the effects of climate change and glyphosate efficacy are well documented for some weeds, little information is available on the response of resistant and susceptible E. colona biotypes to CO2, soil moisture and glyphosate. In order to understand the impact of climate change on the resistant and susceptible E. colona biotypes and glyphosate efficacy in water deficient conditions, the current study was conducted. In our study, both glyphosate-resistant and susceptible biotypes have the same genetic background. The main objectives of the study were 1) to evaluate the growth and physiological responses of glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of E. colona to CO2 and soil moisture conditions, and 2) to evaluate the efficacy of glyphosate when applied on the plants of both biotypes (glyphosate-resistant and susceptible) growing in different soil moisture conditions.

Materials and Methods

Seed collection and development of glyphosate-resistant and susceptible biotypes

A suspected glyphosate-resistant biotype was collected from the research farm of the University of Queensland at Gatton, QLD, Australia (latitude 27.33°S, longitude 152.16°E and altitude 94 m.a.s.l.) in 2016. Resistance was confirmed in a screen-house study, in which plants were sprayed with different doses of glyphosate. Resistant and susceptible biotypes were developed through the cloning method as described by Mutti et al. (in press)42.

Seedling preparation

Two experiments with two experimental runs/repeat (details given below) were conducted: one in growth chambers and the other in the screen-house. Seeds of both resistant and susceptible biotypes of E. colona were planted in plastic trays filled with a commercial potting mix and placed in the screen-house at the Gatton Campus of the University of Queensland, Australia, during the winter and autumn seasons of 2018. After one week, 2-leaf seedlings were transplanted into 15-cm-diameter plastic pots that were filled with a soil mix (potting mix and field soil at 1:1). Only one plant per pot was maintained. The pots were well watered and kept for 2 weeks in the screen-house with average minimum and maximum temperatures of 13.3–15.7 °C and 35.0–35.7 °C, respectively, for the two experimental runs. Two soil moisture conditions were applied after the three-leaf stage through the weighing method43. The 100% and 50% water holding capacity (WHC) were considered as well-watered and water-stressed conditions, respectively.

Experiment I. CO2 and soil moisture: A growth chamber study

The resistant and susceptible biotypes of E. colona were grown in pots placed in two growth chambers set at ambient CO2 (450 ppm) and elevated CO2 (750 ppm) under well-watered and water-stressed conditions. The temperature in both growth chambers was set at 30/20 °C (12 h light/12 h dark), optimum conditions for E. colona42. This experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design with six replications. Physiological and growth characteristics such as plant height, dry biomass, number of leaves, tillers and inflorescences per plant were measured at an interval of 10 days. Number of seeds per plant and photosynthetic pigments were measured at the end of the experiment.

Photosynthetic pigment content was measured with a portable meter and an extractable chlorophyll method44. Two middle leaves of each plant were marked and the relative chlorophyll content was measured using a SPAD meter. At the end of the experiment, the same leaves were used for measuring the amount of chlorophyll a, b and carotenoids using the extractable method proposed by Hiscox and Israelstam45. For each sample, around 0.05 g of fresh leaves were weighed and after adding 5 ml dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), all samples were placed in a water bath at 65 °C for 45 minutes45. The final solution of samples was measured with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, visible spectrophotometer, UV-2550) for detecting the amount of pigments using the wavelengths of 470, 645 and 663 nm for carotenoids, chlorophyll b and chlorophyll a, respectively46. Chlorophyll content was estimated by measuring the correlation of the extractable method and the portable meter value47.

Experiment II. Glyphosate efficacy and soil moisture: A screen-house study

Plants of both biotypes were grown in the screen-house at two soil moisture conditions: well-watered (irrigated daily) and water-stressed (irrigation stopped 2 weeks before glyphosate application). Plants were treated with different glyphosate doses (0, 180, 360, 720 and 1440 g a.e. ha−1) at the 3–4 leaf stage with a Research Track Sprayer (using 108 L water solution/ha). Flat fan nozzles were used in the sprayer. After 24 hours of spraying, all plants were well watered daily. At 2 weeks after spraying, plant survival data were taken with the criterion of survival being at least one green leaf. Surviving plants were cut from the soil surface, placed in paper bags and dried in an oven at 70 °C for 48 h for measuring dry biomass. The experiment was conducted in a randomized complete block design with eight replications.

Statistical analyses

Both experiments were conducted twice (experimental runs). In the experiments, whenever no significant interaction was observed between experimental runs and treatments, data from both runs were pooled for analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results were reported separately when the interaction of experimental run × treatment was significant. SAS (version 9.0.3) was used for ANOVA. Data from both experiments met the assumptions of homogeneity of variance and normality, and did not need transformation.

In experiment I, a three-parameter sigmoidal model was fitted to the height data:

| 1 |

In this equation, f represents height at time x, a is the maximum height at a given time, x50 is the time (days) required to attain 50% height of the maximum height and b indicates the slope.

Leaf, tiller, and inflorescence numbers per plant were modeled using a two-parameter exponential growth equation:

| 2 |

In this equation, f represents the number of leaves, tillers or inflorescences at time x, a is the intercept and b indicates the slope.

Results

Experiment I. CO2 and soil moisture: A growth chamber study

Plant height

Soil moisture and elevated CO2 affected the plant height of both resistant and susceptible biotypes. Plants grown in the well-watered treatment were taller than those grown in the water-stressed treatment at both CO2 concentrations (Fig. 1a,b). In the well-watered treatment, 55 days after planting, the height of the susceptible biotype at elevated CO2 was increased by ~16% (means of experimental runs) compared to plants grown at ambient CO2, but there was no significant increase in the resistant biotype. In the water-stressed treatment, no significant difference was observed between the height of the resistant and susceptible biotypes at both CO2 concentrations. Compared with the well-watered treatment, the height of both resistant and susceptible plants was decreased by ~29% in the water-stressed treatment at elevated CO2 (Fig. 1a,b). The maximum height was observed for the susceptible biotype in the well-watered treatment at elevated CO2.

Figure 1.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the height of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) biotypes of Echinochloa colona. (A) first experimental run (B) second experimental run. High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment. Modeled with the use of equation f = a/(1 + exp (−(x − x50)/b). In this equation f represents height at time x, a is the maximum height at a given time, x50 is the time (days) required for 50% height and b indicates the slope. Estimated parameters are given in Table 1. Vertical bars represent the standard error of means (Experiment I).

The comparison of the slope (b parameter) of the curves shows that in the water-stressed treatment, plant height was mostly constant from 25 days after planting to weed maturity and this was true at both CO2 concentrations (Fig. 1a,b; Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the height of the glyphosate-resistant (R) and glyphosate-susceptible (S) biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment I).

| Treatments | Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | X0 | R2 | |

| Experimental run 1 | ||||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 52.6 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 21.6 ± 8.4 | 0.99 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 63.5 ± 4.4 | 5.4 ± 3.3 | 17.5 ± 5.0 | 0.94 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 50.4 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 23.3 ± 4.8 | 0.99 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 54.6 ± 3.6 | 6.1 ± 2.9 | 18.6 ± 3.7 | 0.97 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | Model could not fit | |||

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 61.8 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 1.8 | 19.3 ± 2.1 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 45.9 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 24.1 ± 0.0 | 0.99 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 62.0 ± 3.8 | 6.8 ± 2.6 | 20.1 ± 2.7 | 0.98 |

| Experimental run 2 | ||||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 45.4 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 17.2 ± 2.4 | 0.99 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 65.2 ± 3.5 | 10.2 ± 6.7 | 23.0 ± 7.2 | 0.92 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 44.1 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 6.0 | 18.3 ± 6.4 | 0.99 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 53.1 ± 5.7 | 7.5 ± 4.2 | 19.7 ± 4.8 | 0.95 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 45.9 ± 1.4 | 3.2 ± 2.9 | 15.7 ± 8.4 | 0.99 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 65.2 ± 6.5 | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 23.2 ± 3.5 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 45.5 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 1.7 | 17.3 ± 3.6 | 0.99 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 62.4 ± 11.5 | 9.9 ± 6.1 | 22.9 ± 6.4 | 0.93 |

High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment.

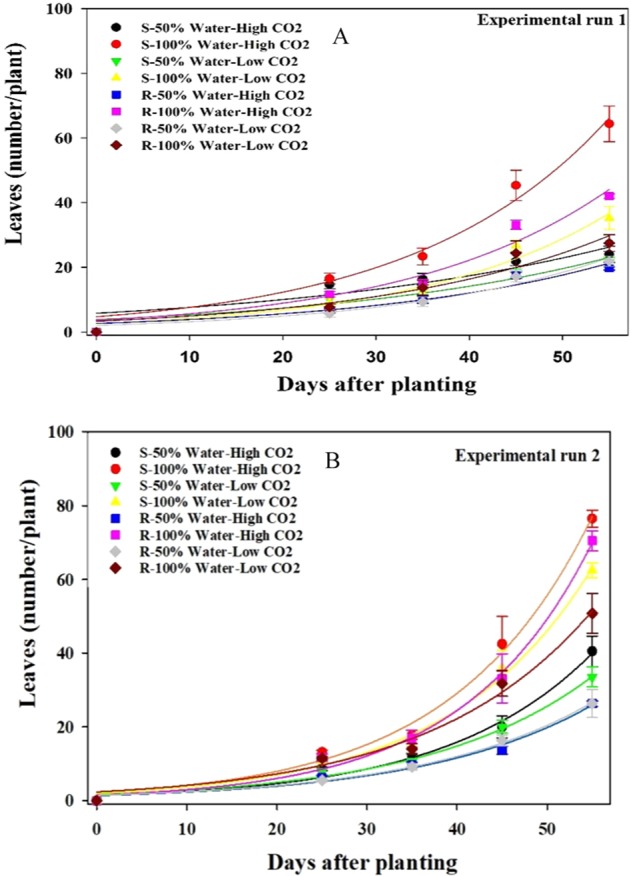

Number of leaves per plant

At elevated CO2, the number of leaves per plant in the well-watered treatment was significantly higher than in the water-stressed treatment at 55 days after planting; 55% and 58% greater for susceptible and resistant biotypes, respectively (Fig. 2a,b). In the water-stressed condition, the susceptible biotype at ambient and elevated CO2 produced 7% and 28% greater number of leaves, respectively, than the resistant biotype (Fig. 2a,b). The comparison of the slope (b parameter) shows that the increase in the number of leaves in the well-watered treatment was faster than in the water-stressed treatment (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the number of leaves per plant in susceptible (S) and resistant (R) biotypes of Echinochloa colona (A) first experimental run (B) second experimental run. High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment. Modeled with the use of equation f = a * exp(b * x). In this equation f represents the number of leaves per plant at time x, a is a constant amount and b indicates the slope. Estimated parameters are given in Table 2. Vertical bars represent the standard error of means (Experiment I).

Table 2.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the number of leaves per plant in the glyphosate-resistant (R) and glyphosate-susceptible (S) biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment I).

| Treatments | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | R2 | |

| Experiment 1 | |||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 5.70 ± 2.40 | 0.02 ± 0.009 | 0.84 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 4.70 ± 1.30 | 0.04 ± 0.005 | 0.98 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 3.82 ± 1.30 | 0.03 ± 0.007 | 0.92 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 2.57 ± 1.05 | 0.04 ± 0.008 | 0.96 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 2.62 ± 1.11 | 0.03 ± 0.008 | 0.92 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 3.55 ± 1.49 | 0.04 ± 0.008 | 0.95 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 2.03 ± 0.73 | 0.04 ± 0.007 | 0.96 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 3.29 ± 1.40 | 0.04 ± 0.009 | 0.92 |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 1.35 ± 0.39 | 0.06 ± 0.005 | 0.98 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 2.17 ± 0.54 | 0.06 ± 0.004 | 0.99 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 1.65 ± 0.36 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | 0.99 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 1.98 ± 0.42 | 0.06 ± 0.004 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 1.35 ± 0.39 | 0.05 ± 0.005 | 0.98 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 1.48 ± 0.34 | 0.07 ± 0.004 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 1.43 ± 0.26 | 0.05 ± 0.003 | 0.99 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 2.37 ± 0.71 | 0.05 ± 0.005 | 0.98 |

High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment.

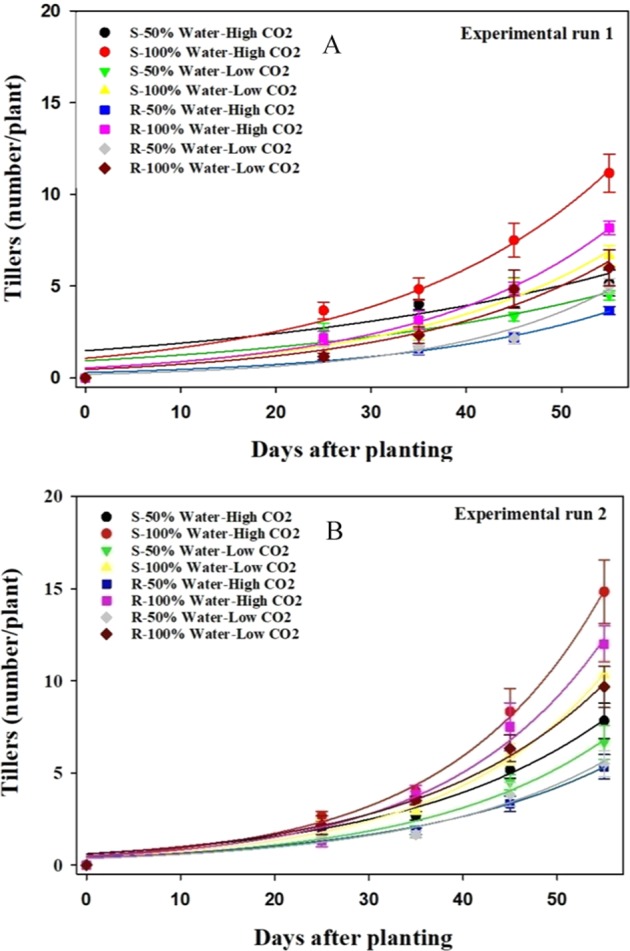

Number of tillers per plant

Regardless of moisture condition, elevated CO2 increased the number of tillers in both biotypes; however, this increase was more obvious in the well-watered treatment than in the water-stressed treatment (Fig. 3a,b, Table 3). At elevated CO2, the susceptible biotype produced 23% more tillers than the resistant biotype in the well-watered treatment (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the number of tillers per plant of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) biotype of Echinohcloa colona. (A) first experimental run (B) second experimental run. High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment. Modeled with the use of equation f = a * exp(b * x). In this equation f represents the number of tillers per plant at time x, a is a constant amount and b indicates the slope. Estimated parameters are given in Table 3. Vertical bars represent the standard error of means (Experiment I).

Table 3.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the number of tillers per plant in the glyphosate-resistant (R) and glyphosate-susceptible (S) biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment I).

| Treatments | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | R2 | |

| Experiment 1 | |||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 1.48 ± 0.69 | 0.020 ± 0.010 | 0.78 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 1.07 ± 0.27 | 0.040 ± 0.005 | 0.97 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.93 ± 0.38 | 0.029 ± 0.008 | 0.87 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.55 ± 0.18 | 0.045 ± 0.006 | 0.96 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.045 ± 0.005 | 0.97 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 0.049 ± 0.004 | 0.98 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.20 ± 0.10 | 0.057 ± 0.010 | 0.95 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.46 ± 0.21 | 0.047 ± 0.009 | 0.94 |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.62 ± 0.21 | 0.046 ± 0.007 | 0.96 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.50 ± 0.09 | 0.061 ± 0.003 | 0.99 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.052 ± 0.008 | 0.96 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 0.058 ± 0.003 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.41 ± 0.14 | 0.046 ± 0.007 | 0.96 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.46 ± 0.15 | 0.059 ± 0.006 | 0.98 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.35 ± 0.13 | 0.050 ± 0.007 | 0.97 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.60 ± 0.13 | 0.050 ± 0.004 | 0.99 |

High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment.

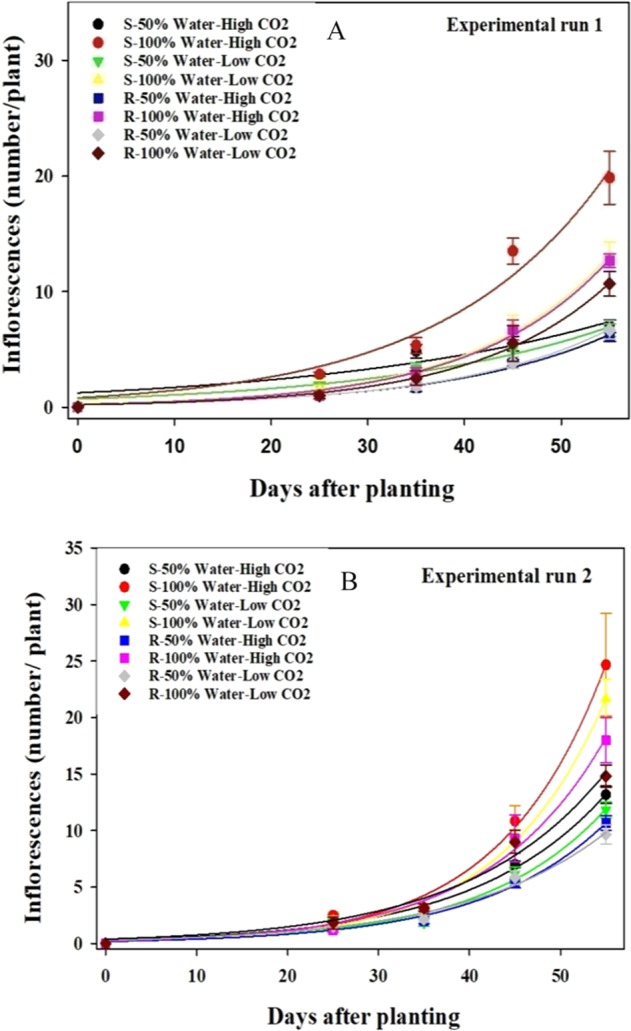

Number of inflorescences per plant

In both biotypes, the increase in soil moisture and CO2 resulted in a significant increase in the number of inflorescences per plant; however, the comparison of the slope (b parameter) of the curves shows that water availability had a more pronounced effect on the number of inflorescences per plant (Table 4). The susceptible biotype produced more inflorescence numbers than the resistant biotype at both CO2 concentrations in the well-watered condition (Fig. 4a,b). At both CO2 concentrations, the lowest number of inflorescences was observed in the resistant biotype under water-stressed conditions (Fig. 4a,b).

Table 4.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the number of inflorescences per plant in the glyphosate-resistant (R) and glyphosate-susceptible (S) biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment I).

| Treatments | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | R2 | |

| Experiment 1 | |||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.24 ± 0.49 | 0.032 ± 0.008 | 0.90 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.81 ± 0.35 | 0.058 ± 0.008 | 0.97 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.70 ± 0.21 | 0.041 ± 0.006 | 0.96 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.071 ± 0.006 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.23 ± 0.06 | 0.059 ± 0.005 | 0.98 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.070 ± 0.004 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.062 ± 0.003 | 0.99 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.072 ± 0.003 | 0.99 |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| S- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.31 ± 0.10 | 0.068 ± 0.006 | 0.98 |

| S- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.087 ± 0.006 | 0.99 |

| S- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | 0.074 ± 0.008 | 0.98 |

| S- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.087 ± 0.005 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- High CO2 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.073 ± 0.005 | 0.99 |

| R- 100% Water- High CO2 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.078 ± 0.006 | 0.99 |

| R- 50% Water- Low CO2 | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 0.064 ± 0.006 | 0.98 |

| R- 100% Water- Low CO2 | 0.39 ± 0.16 | 0.066 ± 0.007 | 0.98 |

High CO2 and Low CO2 denote 750 ppm and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment.

Figure 4.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture on the number of inflorescences per plant of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) biotype of Echinochloa colona. (A) First experimental run (B) second experimental run. High and Low CO2 denote 750 and 450 ppm CO2 concentration, respectively. 50% water represents water-stress treatment and 100% water represents well-water treatment. Modelled with the use of equation f = a * exp (b * x). In this equation f represents the number of inflorescences per plant at time x, a is a constant amount and b indicates the slope. Estimated parameters are given in Table 4. Vertical bars represent the standard error of means (Experiment I).

Number of seeds per plant

In the well-watered treatment, the susceptible biotype produced more seeds than the resistant one under both CO2 concentrations (Table 5). However, no significant difference was observed between their seed production in the water-stressed condition. The decrease in water availability (by 50%) led to a decrease in seed production in the resistant and susceptible biotypes by 67% and 88% at 450 ppm and 45% and 72% at 750 ppm CO2, respectively. Increasing the CO2 concentration did not significantly change the number of seeds per plant in both biotypes.

Table 5.

Effect of different CO2 concentrations and soil moisture conditions on the number of seeds per plant in the glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment I).

| CO2 concentration | Seed production (number per plant) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well water | Water stress | |||

| Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | |

| 450 ppm | 2561 | 1773 | 542 | 585 |

| 750 ppm | 2410 | 1398 | 666 | 601 |

| LSD (0.05%) = 433 | ||||

Total dry shoot biomass

An increase in water availability and CO2 concentration resulted in an increase in shoot biomass of both biotypes but the effect of water availability was more than CO2 concentration (Table 6). The highest amount of shoot biomass was observed for the susceptible biotype in the well-watered treatment under elevated CO2 and the lowest biomass was observed in the water-stressed treatment under ambient CO2 concentration in the susceptible biotype. In the well-watered condition, the biomass of the resistant and susceptible biotypes increased by 12% and 47%, respectively, at elevated CO2 compared with the ambient CO2 concentration. Water stress reduced the biomass of the resistant and susceptible biotypes by 73% and 77%, respectively, at elevated CO2. Under ambient CO2, water stress decreased the total dry biomass of the resistant and susceptible biotypes by 70% and 64%, respectively. The response of the susceptible biotypes was more evident compared with the resistant biotypes in both soil moisture levels and CO2 concentrations.

Table 6.

Effect of carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations and soil moisture on dry biomass of the glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment I).

| CO2 concentration | Dry biomass (g plant−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well water | Water stress | |||

| Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | |

| Experimental run 1 | ||||

| 450 ppm | 1.09 | 1.56 | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| 750 ppm | 2.71 | 1.93 | 0.61 | 0.52 |

| LSD (0.05%) = 0.48 | ||||

| Experimental run 2 | ||||

| 450 ppm | 2.93 | 3.58 | 0.81 | 0.95 |

| 750 ppm | 4.45 | 3.77 | 1.07 | 1.01 |

| LSD (0.05%) = 0.67 | ||||

Photosynthetic pigments

In both experimental runs, significant differences were found between soil moisture treatments for the content of photosynthetic pigments, while no significant differences were observed between CO2 concentrations (Table 7). The well-watered condition significantly increased the amount of total chlorophyll by 23% and 25% in the resistant and susceptible biotypes, respectively, in the ambient CO2 condition.

Table 7.

Content of photosynthetic pigment of the glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of Echinochloa colona grown at different carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations and soil moisture in growth chambers (Experiment I).

| Photosynthetic pigments content (mg g−1 dry weight) | Well water | Water stress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | ||

| Experimental run 1 | |||||

| Carotenoids | 450 ppm | 1.77 | 1.77 | 1.44 | 1.43 |

| 750 ppm | 1.81 | 1.79 | 1.47 | 1.44 | |

| LSD (0.05%) = 0.07 | |||||

| Chlorophyll a | 450 ppm | 30.55 | 30.53 | 24.94 | 24.69 |

| 750 ppm | 31.34 | 30.88 | 25.36 | 24.86 | |

| LSD (0.01%) = 1.30 | |||||

| Chlorophyll b | 450 ppm | 6.76 | 6.76 | 5.21 | 5.14 |

| 750 ppm | 6.96 | 6.86 | 5.33 | 5.19 | |

| LSD (0.05%) = 0.36 | |||||

| Chlorophyll total | 450 ppm | 37.32 | 37.3 | 30.16 | 29.84 |

| 750 ppm | 38.2 | 37.75 | 30.7 | 30.06 | |

| LSD (0.05%) = 1.66 | |||||

| Experimental run 2 | |||||

| Carotenoids | 450 ppm | 2.42 | 2.39 | 1.71 | 1.8 |

| 750 ppm | 2.41 | 2.46 | 1.71 | 1.8 | |

| LSD (0.05%) = 0.19 | |||||

| Chlorophyll a | 450 ppm | 41.87 | 41.35 | 29.49 | 31.09 |

| 750 ppm | 41.69 | 42.54 | 29.6 | 31.03 | |

| LSD (0.01%) = 3.32 | |||||

| Chlorophyll b | 450 ppm | 9.9 | 9.76 | 6.47 | 6.9 |

| 750 ppm | 9.85 | 10.09 | 6.5 | 6.9 | |

| LSD (0.05%) = 0.92 | |||||

| Chlorophyll total | 450 ppm | 51.78 | 51.11 | 35.97 | 38.01 |

| 750 ppm | 51.55 | 52.63 | 36.11 | 37.93 | |

| LSD (0.05%) = 4.25 | |||||

Experiment II. Glyphosate efficacy and soil moisture: A screen-house study

Biomass data showed that glyphosate efficacy was significantly decreased in the water-stressed condition at all glyphosate doses (Table 8). The resistant biotype in the well-watered treatment had 19% survival at 1440 g ha−1 glyphosate (twice of the recommended dose), but this survival degree increased in the water-stressed treatment by 62% (Table 8). For the susceptible biotype, plant biomass decreased by 62% and 92% at 720 and 1440 g ha−1 glyphosate, respectively, in the water-stressed condition, while at the same herbicide doses, no plant survived in the well-water condition (Table 9).

Table 8.

The effect of different doses of glyphosate and soil moisture on plant survival of the glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment II).

| Dose (g a.e. ha−1) | Dry biomass (g plant−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-water | Water-stress | |||

| Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | |

| control | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 180 | 93.8 | 100.0 | 93.8 | 100.0 |

| 360 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 100.0 |

| 720 | 0 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 100.0 |

| 1440 | 0 | 18.8 | 25.0 | 81.2 |

| LSD (0.05) = 16.43 | ||||

Well-water represents daily irrigation, in water-stress irrigation stopped 2 weeks before glyphosate application.

Table 9.

The effect of different doses of glyphosate and soil moisture on total biomass of the glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of Echinochloa colona (Experiment II).

| Dose (g a.e. ha−1) | Dry biomass (g plant−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-water | Water-stress | |||

| Susceptible | Resistant | Susceptible | Resistant | |

| 0 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| 180 | 0.24 (48%) | 0.32 (24%) | 0.16 (50%) | 0.29 (5%) |

| 360 | 0.17 (63%) | 0.19 (54%) | 0.13 (58%) | 0.20 (35%) |

| 720 | 0 (100%) | 0.11 (71%) | 0.12 (62%) | 0.14 (52%) |

| 1440 | 0 (100%) | 0.030 (93%) | 0.02 (92%) | 0.06 (80%) |

| LSD = 0.09 | ||||

The reduction (%) was presented in parenthesis.

Well-water represents daily irrigation, in water-stress irrigation stopped 2 weeks before glyphosate application.

Discussion

Elevated CO2 resulted in taller plants of both susceptible and resistant E. colona biotypes with more tillers, leaves, and biomass, but seed production was not affected by the increased CO2 concentration. Generally, elevated CO2, when considered alone, leads to increased numbers of leaves and inflorescences, height and total biomass, which could be attributed to increased photosynthesis and water use efficiency and decreased transpiration through reducing stomatal conductance48–52. While some studies reported an increase in seed production by elevated CO2 4,5, our study found no significant difference. In C4 species, because of their ability to concentrate CO2 via their photosynthesis pathway53, increasing the external CO2 concentration has little effect on net photosynthesis54, but it should not be assumed that C4 plants do not have the ability to use high CO2 amounts55.

Water deficit is one of the most concerning issues surrounding climate change and may interfere with plant growth and development. The current study observed that water deficit resulted in the reduction of growth parameters and consequently seed production, especially for the susceptible biotype. Other studies also considered the importance of water deficiency on weed growth56,57. The amount of photosynthetic pigments was significantly decreased by the reduction in water availability. Water stress can affect the synthesis of chlorophyll, the electron transport chain and consequently, synthesis of all proteins and enzymes, such as carboxylase, that have essential roles in photosynthesis29,58. How the pigment amount is affected may be related to the competitive ability of weeds, as a species with higher amounts of photosynthetic pigments may be more competitive46.

The interaction effect of soil moisture and CO2 concentration significantly influenced all measured growth parameters and seed production. The effect of elevated CO2 in increasing plant growth is likely to happen at the optimum temperature for growth and sufficient water availability14,59. In the current study, the effect of soil moisture and CO2 concentration was examined at the optimum temperature for E. colona. Water availability was found to affect weed growth more than CO2 concentration. Elevated CO2 can be helpful for the vegetative growth of plants but cannot compensate for the adverse effect of water stress on them56. Leakey et al. suggested that the increase in the growth potential of C4 plants by elevated CO2 depends on the decrease in water use and reduction in drought stress, and not by the direct effect of increased photosynthesis57. The water requirement of weeds will increase under rising CO2 and temperature56. Plants in water stress conditions cannot properly use high CO2 concentration as much as those that are well watered, due to the lower stomatal conductance caused by less guard cell turgescence. Therefore, CO2 uptake will decrease in these plants12,60. The difference in seed production between the resistant and susceptible biotypes was not significant in the water-stressed condition at both CO2 concentrations. In the water-stressed condition, increasing CO2 concentration via decreasing stomatal conductance and increasing water use efficiency may allow plants to produce more seeds, but total biomass may always be lower compared with plants grown in well-watered conditions60.

In both biotypes, growth and seed production were enhanced by increasing CO2 concentration and water availability. In the well-watered treatment, the stimulation of photosynthesis from increased CO2 concentration in our study was more evident in the susceptible than in the resistant biotype. Despite higher vegetative growth of the susceptible biotype, no difference was observed in seed production between biotypes in the water-stressed treatment. It can be concluded that the resistant biotype allocated more photosynthetic resources to seed production compared with vegetative growth in the stressed condition. Potvin (1986) mentioned a strategy of investing more resources to inflorescence development (versus leaves) in E. crus-galli plants due to the importance and critical role of seed production in population dynamics61. The link between plant size and evolutionary fitness is the ability of plants to allocate resources to reproduction3.

In Experiment II, reducing soil moisture content resulted in a decrease in the efficacy of glyphosate. This response could be caused by less absorption and translocation of glyphosate as the herbicide is mainly translocated by vascular transportation62. Tanpipat et al. also claimed that water stress via reducing leaf area can affect glyphosate uptake41. The requirement of high doses of glyphosate in the water-stressed condition may be related to the increase in the concentration gradient across the cuticle, consequently leading to more glyphosate uptake63. Using high glyphosate rates in water stress conditions may cause a high risk of producing resistant biotypes.

It is predicted that climate change will have a significant impact on weed management strategies in the future22. The latest studies on climate change in regards to weeds suggest that focusing on drought-resistant weed biotypes seems to be a more logical resolution than other biotypes. Understanding weed fitness could help to predict the dynamics of herbicide-resistant weeds and their management64. Species that showed adaptation to drought conditions were less adversely affected by climate change and were able to compete better in dry soil rather than species which adapted to wet soil moisture conditions65. In addition, the current study observed that herbicide efficacy was reduced by decreasing water availability. Therefore, more studies on herbicide efficacy in climate change conditions should be considered.

Conclusions

Environmental changes can affect the physiological and growth processes of weeds and their responses to herbicides. E. colona biotypes used in this study showed greater vegetative growth in response to elevated CO2. In both biotypes, seed production and photosynthesis pigments were not affected by the increased CO2 concentration. However, the water-stress condition caused a significant decrease in growth parameters, seed production and glyphosate efficacy in both biotypes. The results of this study suggest that the predicted climate change can make this weed more noxious and competitiveness. It is possible that increased vegetative growth of weeds combined with water deficiency caused by climate change reduces the herbicide uptake and translocation and consequently, decrease herbicide efficacy. More studies based on different climate change factors need to be conducted to elucidate the role of environmental parameters and nutrition on opportunistic weeds’ responses. A better understanding of how weeds respond to climate change based on known tolerance ranges and climatic selection pressures is suggested for developing effective weed management strategies.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: B.S.C. Data curation: A.M., M.M. Formal analysis: A.M. Funding acquisition: B.S.C. Methodology: B.S.C. Resources: B.S.C. Writing ± original draft: M.M. Writing ± review & editing: A.M., B.S.C.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nelson GC, et al. Climate change effects on agriculture: Economic responses to biophysical shocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:3274–3279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222465110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauhan, B. S., Mahajan, G., Randhawa, R. K., Singh, H. & Kang, M. S. Global warming and its possible impact on agriculture in India. In Advances in agronomy. Vol. 123 65-121 (Elsevier, 2014).

- 3.Clements DR, Ditommaso A. Climate change and weed adaptation: can evolution of invasive plants lead to greater range expansion than forecasted? Weed Res. 2011;51:227–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2011.00850.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters K, Breitsameter L, Gerowitt B. Impact of climate change on weeds in agriculture: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014;34:707–721. doi: 10.1007/s13593-014-0245-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson LJ, Macfadyen S, Hoffmann AA. Predicting the effects of climate change on natural enemies of agricultural pests. Biol. Control. 2010;52:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Barnard, P. & Moomaw, W. R. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience, 10.1093/biosci/biz088 (2019).

- 7.- National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration Research. Recent Monthly Average Mauna Loa CO2 Report. Available at, www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/ (NOAA, 2019)

- 8.Idso CD, Idso SB, Balling RC., Jr. An intensive two-week study of an urban CO2 dome in Phoenix, Arizona, USA. Atmos. Environ. 2001;35:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00412-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziska LH, Faulkner S, Lydon J. Changes in biomass and root: shoot ratio of field-grown Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), a noxious, invasive weed, with elevated CO2: implications for control with glyphosate. Weed Sci. 2004;52:584–588. doi: 10.1614/WS-03-161R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachauri, R. K. et al. Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (IPCC, 2014).

- 11.Ghannoum O, von Caemmerer S, Barlow EW, Conroy JP. The effect of CO2 enrichment and irradiance on the growth, morphology and gas exchange of a C3 (Panicum laxum) and a C4 (Panicum antidotale) grass. Funct. Plant Biol. 1997;24:407–407. doi: 10.1071/PP96077_CO. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampton JG, Conner AJ, Boelt B, Chastain TG, Rolston P. Climate Change: Seed Production and Options for Adaptation. Agricult. 2016;6:33. doi: 10.3390/agriculture6030033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wand SJ, Midgley GF, Jones MH, Curtis PS. Responses of wild C4 and C3 grass (Poaceae) species to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration: a meta‐analytic test of current theories and perceptions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 1999;5:723–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00265.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nybakken L, Julkunen‐Tiitto R. Gender differences in Salix myrsinifolia at the pre‐reproductive stage are little affected by simulated climatic change. Physiol. plantarum. 2013;147:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker J, Hartwell Allen L, Boote K, Pickering N. Rice responses to drought under carbon dioxide enrichment. 1. Growth and yield. Glob. Chang. Biol. 1997;3:119–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1997.00058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houghton, J., Jenkins, G. & Ephraums, J. Climate change: the IPCC scientific assessment Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK (1990).

- 17.Naumburg E, Loik ME, Smith SD. Photosynthetic responses of Larrea tridentata to seasonal temperature extremes under elevated CO2. New Phytol. 2004;162:323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01023.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paucar-Caceres A, Bandala ER, Wright GH. The impact of global climate change on water quantity and quality: A system dynamics approach to the US–Mexican transborder regionAuthor-Name: Duran-Encalada, JA. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017;256:567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2016.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vörösmarty CJ, Green P, Salisbury J, Lammers RB. Global water resources: vulnerability from climate change and population growth. Sci. 2000;289:284–288. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb RJ, McKellar R, Kay R. Climate change adaptation in Australia: experience, challenges and capability development. Australas. J. Env. Man. 2013;20:320–337. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2013.835285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Climate change in Australia. Technical Report. Available at, www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au (CSIRO, 2007)

- 22.Ramesh K, Matloob A, Aslam F, Florentine SK, Chauhan BS. Weeds in a changing climate: vulnerabilities, consequences, and implications for future weed management. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:95. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehrtens J, Schulte M, Hurle K. Unkrautflora in mais. Gesunde Pflanz. 2005;57:206–218. doi: 10.1007/s10343-005-0097-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otte A, Bissels S, Waldhardt R. Samen-, Keimungs-und Habitateigenschaften: Welche Parameter erklären Veränderungstendenzen in der Häufigkeit von Ackerwildkräutern in Deutschland. J. Plant Dis. Protect. 2006;20:507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauhan BS, Johnson DE. Seed germination ecology of junglerice (Echinochloa colona): a major weed of rice. Weed Sci. 2009;57:235–240. doi: 10.1614/WS-08-141.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghannoum O. C4 photosynthesis and water stress. Ann. Bot. 2008;103:635–644. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marenco Mendoza, R. & Lopes, N. F. Fisiologia vegetal: fotossintese respiracao relacoes hidricas nutricao mineral. (UFV, 2005).

- 28.Larcher, W. Physiological plant ecology: ecophysiology and stress physiology of functional groups. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2003).

- 29.Ohashi Y, Nakayama N, Saneoka H, Fujita K. Effects of drought stress on photosynthetic gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and stem diameter of soybean plants. Biol. Plant. 2006;50:138–141. doi: 10.1007/s10535-005-0089-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qaderi MM, Reid DM. Growth and physiological responses of canola (Brassica napus) to UV‐B and CO2 under controlled environment conditions. Physiol. Plant. 2005;125:247–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00566.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qaderi MM, Kurepin LV, Reid DM. Growth and physiological responses of canola (Brassica napus) to three components of global climate change: temperature, carbon dioxide and drought. Physiol. Plant. 2006;128:710–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00804.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pautasso M, et al. Plant health and global change–some implications for landscape management. Biol. Rev. 2010;85:729–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenzweig C, et al. Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:3268–3273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222463110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holm, L. G., Plucknett, D. L., Pancho, J. V. & Herberger, J. P. The world’s worst weeds. Distribution and biology. (University press of Hawaii, 1977).

- 35.Cameron, J. & Storrie, A. Summer fallow weed management. Grains Research and Development Corporation GRDC (2014).

- 36.Widderick MJ, Bell KL, Boucher LR, Walker SR. Control by glyphosate and its alternatives of glyphosate‐susceptible and glyphosate‐resistant Echinochloa colona in the fallow phase of crop rotations in subtropical Australia. Weed Biol. Manag. 2013;13:89–97. doi: 10.1111/wbm.12014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maun MA, Barrett SCH. The biology of Canadian weeds: 77. Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Beauv. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1986;66:739–759. doi: 10.4141/cjps86-093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chauhan BS, Johnson DE. Growth and reproduction of junglerice (Echinochloa colona) in response to water stress. Weed Sci. 2010;58:132–135. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-09-00016.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss, S. R. Herbicide-resistant weeds. Weed management handbook. 9 (2002).

- 40.Ahmadi MS, Haderlie LC, Wicks GA. Effect of growth stage and water stress on barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli) control and on glyphosate absorption and translocation. Weed Sci. 1980;28:277–282. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500055284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanpipat S, Adkins SW, Swarbrick JT, Boersma M. Influence of selected environmental factors on glyphosate efficacy when applied to awnless barnyard grass (Echinochloa colona (L.) Link) Aus. J. Agric. Res. 1997;48:695–702. doi: 10.1071/A96141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mutti, N., Mahajan, G. & Chauhan, B. Seed germination ecology of glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible biotypes of Echinochloa colona L.(Link) in Australia. Weed Sci. (accepted) (2019).

- 43.Steadman KJ, Ellery AJ, Chapman R, Moore A, Turner NC. Maturation temperature and rainfall influence seed dormancy characteristics of annual ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2004;55:1047–1057. doi: 10.1071/AR04083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geider, R. J. & Osborne, B. A. “Measuring Photosynthetic Pigments,” In Algal Photosynthesis, 107–121. (Springer, 1992).

- 45.Hiscox JD, Israelstam GF. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll from leaf tissue without maceration. Can. J. Bot. 1979;57:1332–1334. doi: 10.1139/b79-163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaspary TE, Lamego FP, Cutti L, Aguiar ACM, Bellé C. Determination of photosynthetic pigments in fleabane biotypes susceptible and resistant to the herbicide glyphosate. Planta Daninha. 2014;32:417–426. doi: 10.1590/S0100-83582014000200020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smillie RM, Nott R. Salt tolerance in crop plants monitored by chlorophyll fluorescence in vivo. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:1049–1054. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.4.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clifford SC, et al. Effects of elevated CO2, drought and temperature on the water relations and gas exchange of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) stands grown in controlled environment glasshouses. Physiol. Plant. 2000;110:78–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2000.110111.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guy RD, Reid DM. Photosynthesis and the influence of CO2‐enrichment on δ13C values in a C3 halophyte. Plant Cell Environ. 1986;9:65–72. doi: 10.1111/1365-3040.ep11614337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawlor, D. W. & Mitchell, R. A. Crop ecosystem responses to climatic change: wheat. Climate change and global crop productivity, 57–80 (2000).

- 51.Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Ort DR. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: plants FACE the future. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:591–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrison, J. I. L. Stomatal response to increased CO2 concentration. J. Exp. Bot. (49), 443–452, www.jstor.org/stable/23695977 (1998).

- 53.Taiz, L. & Zeiger, E. Plant physiology. 3rd edn. Ann. Bot. 91, 750–751 (1991).

- 54.Ziska LH, Bunce JA. Influence of increasing carbon dioxide concentration on the photosynthetic and growth stimulation of selected C4 crops and weeds. Photosynth. Res. 1997;54:199–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1005947802161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knapp, A. K., Hamerlynck, E. P. & Owensby, C. E. Photosynthetic and water relations responses to elevated CO2 in the C4 grass Andropogon gerardii. Inter. J. Plant Sci. 154, 459–466, www.jstor.org/stable/2995622 (1993).

- 56.Broughton KJ, et al. Warming alters the positive impact of elevated CO2 concentration on cotton growth and physiology during soil water deficit. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017;44:267–278. doi: 10.1071/FP16189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leakey AD, et al. Elevated CO2 effects on plant carbon, nitrogen, and water relations: six important lessons. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:2859–2876. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reddy AR, Chaitanya KV, Vivekanandan M. Drought-induced responses of photosynthesis and antioxidant metabolism in higher plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2004;161:1189–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drake BG, Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Long SP. More efficient plants: a consequence of rising atmospheric CO2? Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1997;48:609–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh Rishi P., Prasad P. V. Vara, Reddy K. Raja. Advances in Agronomy. 2013. Impacts of Changing Climate and Climate Variability on Seed Production and Seed Industry; pp. 49–110. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Potvin C. Biomass allocation and phenological differences among southern and northern populations of the C4 grass Echinochloa crus-galli. J. Ecol. 1986;74:915–923. doi: 10.2307/2260223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Norris, R. F. Influence of soil moisture on activity of diclofop-methyl. In Abstr. Weed Sci. Soc. Am. 102–103 (1977).

- 63.Merritt CR. The influence of form of deposit on the phytotoxicity of MCPA, paraquat and glyphosate applied as individual drops. Ann. App. Biol. 1982;101:527–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1982.tb00854.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neve P, Diggle AJ, Smith FP, Powles SB. Simulating evolution of glyphosate resistance in Lolium rigidum II: past, present and future glyphosate use in Australian cropping. Weed Res. 2003;43:418–427. doi: 10.1046/j.0043-1737.2003.00356.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiese AF, Vandiver CW. Soil moisture effects on competitive ability of weeds. Weed Sci. 1970;18:518–519. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500078590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]