Abstract

Randall’s plaque (RP; subepithelial calcification) appears to be an important precursor of kidney stone disease. However, RP cannot be noninvasively detected. The present study investigated candidate biomarkers associated with extracellular vesicles (EVs) in the urine of calcium stone formers (CSFs) with low (<5% papillary surface area) and high (≥5% papillary surface area) percentages of RP and a group of nonstone formers. RPs were quantitated via videotaping and image processing in consecutive CSFs undergoing percutaneous surgery for stone removal. Urinary EVs derived from cells of different nephron segments of CSFs (n = 64) and nonstone formers (n = 40) were quantified in biobanked cell-free urine by standardized and validated digital flow cytometer using fluorophore-conjugated antibodies. Overall, the number of EVs carrying surface monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) were significantly lower in CSFs compared with nonstone former controls (P < 0.05) but did not differ statistically between CSFs with low and high RPs. The number of EVs associated with osteopontin did not differ between any groups. Thus, EVs carrying MCP-1 and NGAL may directly or indirectly contribute to stone pathogenesis as evidenced by the lower of these populations of EVs in stone formers compared with nonstone formers. Validation of EV-associated MCP-1 and NGAL as noninvasive biomarkers of kidney stone pathogenesis in larger populations is warranted.

Keywords: extracellular vesicles, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, nephrolithiasis, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, Randall’s plaque, urinary stone disease

INTRODUCTION

Randall’s plaque (RP), subepithelial calcifications within the renal papillum that can act as an anchor for calcium oxalate (CaOx) and calcium phosphate (CaP) stones, is considered an important precursor of stone formation (26, 32). However, subsets of calcium stone formers (CSFs) lack significant RPs. In a recent surgical series of 42 consecutive CSFs, 32 patients (76%) had low amounts of RPs (<5% of papillary surface involved) and only 10 patients (24%) belonged to the high-RP group (≥5% of papillary surface involved) (48). These patients with low amounts of RP may have other mechanisms of kidney stone formation, perhaps involving renal tubular plugs or other as yet unknown renal cellular and molecular pathways.

Urinary extracellular vesicles (EVs) such as exosomes and microvesicles have emerged over the past decade as a promising source of biomarkers for renal diseases (8, 35). Exosomes (typically 30–150 nm in size) are formed by inward budding of the plasma membrane and intracellular membranes into multivesicular bodies. After intracellular processing, subsequent exocytosis of the multivesicular bodies results in exosome release to the extracellular space (1, 8, 34, 40). Microvesicles (or ectosomes) are slightly larger (40–1,000 nm) and are produced by outward budding of the plasma membrane (1, 34, 35, 40, 52). Bioactive molecules within EVs include proteins, receptors, nucleic acids, and lipids, all of which appear to reflect the activation state of the cell of origin. EVs can withstand adverse conditions, including extreme pH, long-term storage, and multiple freeze thaw cycles, all without losing their physical properties, making them an attractive source of potential cellular biomarkers (35, 38). The present study tested the hypothesis that EVs containing candidate biomarkers for inflammation [monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1] (49), renal epithelial cell injury [neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL)] (6), or pathological calcification [osteopontin (OPN)] (45) might reflect intrarenal stone formation processes and differ between CSFs and nonstone-forming controls and also differ between low- and high-RP stone formers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Urine sample collection, preparation, and storage.

Twenty-four-hour urine samples from CSFs (n = 64) and age/sex-matched stone-free controls (n = 40, nonstone formers) were collected with toluene as a preservative, with aliquots centrifuged at 2,100 g/3,400 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to remove the cells and larger molecular weight protein aggregates before freezing (−80°C) by the Mayo Clinic O’Brien Urology Research Center. Frozen cell-free urine from 33 male and 31 female CSFs with RP mapping data and 20 male and 20 female matched nonstone formers were included in the present study. The renal papillary surface area involved with RPs was assessed via videotaping at the time of percutaneous stone removal, including quantitative image processing as previously described (48). Previous studies have confirmed that urinary EVs are stable under these storage conditions (23). Urine biochemistry on the 24-h urine samples was performed at the Mayo Clinic Renal Testing Laboratory (Rochester, MN) using standard protocols.

Antibodies used in the study.

Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse anti-human MCP-1 (catalog no. 502604, BioLegend, San Diego, CA), rabbit anti-human NGAL (catalog no. bs-0444R-PE, Bioss Antibodies, Woburn, MA), mouse anti-human OPN (catalog no. IC14331P, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), FITC-conjugated recombinant annexin V (marker for vesicles carrying surface phosphatidylserine, catalog no. 556419, BD Pharminagen, San Jose, CA), rabbit anti-human aquaporin-1 (marker of the simple squamous epithelium of the descending limb of Henle, catalog no. orb15121, Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-human aquaporin-2 (marker of principal cells of the collecting duct, catalog no. orb13806, Biorbyt), rabbit polyclonal anti-human urate transporter (URAT)1 (marker of the simple cuboidal epithelium of the proximal convoluted tubule, catalog no. bs-10357R-FITC, Bioss Antibodies], mouse anti-human uromodulin (marker of the thick ascending loop of Henle, catalog no. LS-B3105, Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA), rabbit polyclonal anti-human SLC12A3 (marker of the simple cuboidal epithelium of the distal convoluted tubule, catalog no. bs-7694R-FITC, Bioss Antibodies), and rabbit anti-human cytokeratin-19 (marker of the transitional epithelium of the papillary duct, catalog no. bs-2190R-FITC, Bioss Antibodies) antibodies were used in this study.

Characterization of urinary EVs by digital flow cytometer.

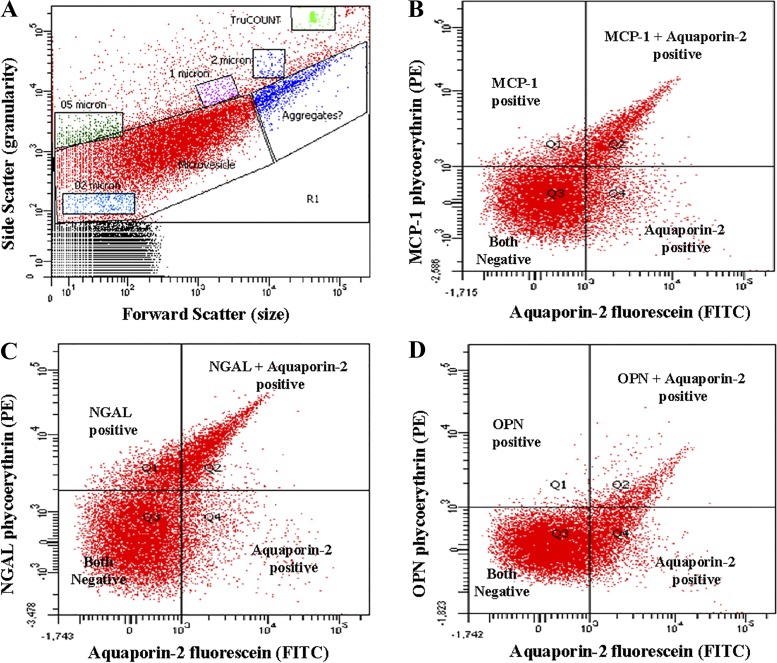

A recently published and validated method for the quantification and characterization of renal parenchymal-derived urinary EVs was used in the present study (23). In brief, EV size was determined using 0.2-, 0.5-, 1-, and 2-µm flurosbrite microparticles (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) as internal standards. For quantification of EVs in diluted urine, sample tubes were spiked with known counts of 4.2-µm diameter TruCOUNT (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) beads. HEPES-Hanks (H/H) buffer (pH 7.4) and, to reduce chemical particles and instrument noise, antibody solutions were all filtered twice using a 0.2-µm membrane filter (24). Flow cytometry settings for EV detection were identical to those of prior studies (22, 23). The flow rate (low, medium, or high) was set predominantly at high with a threshold rate (events per second per sample tube) of fewer than 1,000 events. If the threshold rate was more than 1,000 events per second, the flow rate was reduced to low or medium to keep the events per second fewer than 1,000 events per second. Unfiltered Isoton II diluent (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) was used in the cytometer. The volume of urine used for EV quantification ranged from 5 to 80 µL based on prior EV concentration check using 20 µL urine with annexin V-fluorescein. Thus, enough urine was used to obtain a minimum of 2,500 annexin V-positive events, with the total number of events in the EV gate always kept between 10,000 and 30,000. All cell-free biobanked urine was thawed and diluted with twice-filtered H/H buffer (pH 7.4) to obtain a 100 µL sample. These samples were incubated with 3 µL antibodies to localize the urinary cell of origin as follows: URAT1 (1:20 dilution in sterile water) for the proximal tubule (14), aquaporin-1 (1:5 dilution in PBS) for the descending thin limb (2, 31), uromodulin (1:30 dilution in PBS) for the thick ascending limb (37), SLC12A3 (1:20 dilution in sterile water) for the distal convoluted tubule (41), aquaporin-2 (1:5 dilution in PBS) for principle cells of the collecting duct (2), and cytokeratin-19 (1:20 dilution in PBS) for the epithelium of papillary duct (13, 20). Selected biomarker antibodies (MCP-1, NGAL, or OPN, 3 µL) were also added, and, after being mixed (80 s), tubes were incubated in the dark for 30 min followed by dilution with 800 µL of twice-filtered H/H buffer and the addition of a known quantity of TruCOUNT beads (100 µL). During flow cytometry analysis, the stopping gate was set at 1,500 TruCOUNT beads or 380 s. The absolute counts of EVs expressing the markers of interest were expressed as EV per microliter of urine. EVs positive for dual markers (e.g., nephron-specific location marker and a candidate) were found in the Q2 (dual marker positive) segment of the fluorescence dot plot (<1 µm; Fig. 1). The total number of EVs coexpressing two markers was calculated using the following formula:

where Q2 denotes events recorded in the Q2 quadrant from the 0.2 to 1 µm size (microvesicles) gate of the scatterplot, “TruCOUNT beads” denotes the number of beads analyzed, “bead count” denotes the number of known quantity of TruCount beads added into the test tube, “volume” denotes the volume of urine sample used, and “dilution” is the volume of buffer and beads solution to volume of urine in the sample tube.

Fig. 1.

Example scatterplots (A) and fluorescence dot (quadrant) plots (B–D) from FACSCanto flow cytometry. Fluorescent dot plots [quadrant derived from the microvesicle gate (contain 0.2 to 1 μm size vesicles) of A, which contains a substantial portion of extracellular vesicles] showing fluorophore spectra separates. B: monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 plus aquaporin-2 (a specific marker of collecting duct cell-derived extracellular vesicles). C: neutrophil gelatinase-associated protein (NGAL) plus aquaporin-2. D: osteopontin plus aquaporin-2. A similar pattern of scatterplot and fluorescence dot was observed with other marker combinations in all study participants.

The value obtained from the formula was expressed as EVs positive for double marker (Q2) per microliter of urine. EVs were standardized by correcting for urinary creatinine and were ultimately expressed as EVs per milligram of creatinine.

Statistical analysis.

Data analysis was performed using JMP Pro software (version 10.0, SAS, Cary, NC). Differences between baseline clinical characteristics and urine biochemistry among the study groups were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis test, with the data represented as means (SD). P values of <0.05 were reported as statistically significant. Urinary EV data are expressed as medians (25th, 75th percentile). Differences between groups were analyzed with a Wilcoxon (rank sum) test, with P values of <0.05 deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

The median ages of study participants were similar in both groups (Tables 1 and 2). The body mass index as well as 24-h urinary excretions of calcium, creatinine, phosphate, and supersaturation for CaOx and uric acid were significantly greater (P < 0.05), whereas urinary pH and osmolality were significantly lower (P < 0.05), in CSFs compared with age/sex-matched nonstone formers (Table 1). Twenty-four-hour urine calcium and creatinine excretions were significantly greater (P < 0.05), whereas urinary sodium was nominally (P = 0.05) greater, in high-plaque CSFs compared with low-plaque CSFs (Table 2). All other urine chemistry measures did not differ between groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants

| Nonstone Formers | Calcium Stone Formers | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 40 | 64 | |

| Age at urine collection, yr | 62.2 (13.1) | 62.7 (12.0) | 0.87 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 20 (50.0%) | 31 (48.4%) | |

| Male | 20 (50.0%) | 33 (51.6%) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.8 (4.3) | 29.8 (6.6) | 0.02* |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 122.1 (16.5) | 126.6 (19.4) | 0.30 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 73.7 (9.3) | 70.4 (12.6) | 0.13 |

| Urine calcium, mg/24 h | 150.5 (85.2) | 231.1 (129.6) | <0.01* |

| Urine chloride, mmol/24 h | 121.8 (59.3) | 134.5 (81.0) | 0.65 |

| Urine citrate, mg/24 h | 685.2 (399.0) | 564.6 (344.8) | 0.15 |

| Urine creatinine, mg/24 h | 1,052.9 (498.0) | 1,363.4 (636.0) | 0.01* |

| Urine uric acid, mg/24 h | 452.3 (214.0) | 524.3 (231.3) | 0.11 |

| Urine osmolality, mosmol/kgH2O | 545.1 (227.0) | 405.0 (222.4) | 0.01* |

| Urine oxalate, mmol/24 h | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.71 |

| Urine phosphate, mg/24 h | 656.7 (365.0) | 858.4 (459.0) | 0.01* |

| Urine potassium, mmol/24 h | 68.5 (50.1) | 59.0 (29.4) | 0.39 |

| Urine sodium, mmol/24 h | 130.5 (60.1) | 146.8 (91.4) | 0.61 |

| Urine sulfate, mmol/24 h | 18.3 (18.3) | 17.6 (8.8) | 0.54 |

| Urine pH | 6.4 (0.6) | 6.0 (0.6) | <0.01* |

| Urine volume, mL | 2,023.1 (608.0) | 2,080.5 (814.8) | 0.76 |

| Urine calcium phosphate (supersaturation), dG | −0.6 (1.1) | −0.4 (1.5) | 0.25 |

| Urine uric acid (supersaturation), dG | −2.9 (3.8) | 0.0 (2.7) | <0.01* |

| Urine calcium oxalate (supersaturation), dG | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.7) | <0.01* |

Data are presented as means (SD). dG, ΔGibbs. Statistical differences between groups were determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical significance.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of idiopathic CSFs with low (<5% papillary surface area) plaque and high (≥5% papillary surface area) plaque numbers

| CSFs With Low Plaque Numbers | CSFs With High Plaque Numbers | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 43 | 21 | |

| Age at urine collection | 62.5 (12.4) | 63.3 (11.6) | 0.75 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 23 (53.5%) | 8 (38.1%) | |

| Male | 20 (46.5%) | 13 (61.9%) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.0 (6.8) | 29.2 (6.2) | 0.69 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 127.0 (20.1) | 125.8 (18.1) | 0.66 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 68.5 (11.7) | 74.2 (13.8) | 0.09 |

| Urine calcium, mg/24 h | 205.5 (114.3) | 283.4 (145.5) | 0.03* |

| Urine chloride, mmol/24 h | 120.8 (70.8) | 162.7 (94.3) | 0.07 |

| Urine citrate, mmol/24 h | 596.6 (353.3) | 499.2 (325.0) | 0.35 |

| Urine creatinine, mg/24 h | 1,273.3 (582.8) | 1,547.9 (712.3) | 0.04* |

| Urine uric acid, mg/24 h | 504.4 (221.5) | 565.3 (250.6) | 0.16 |

| Urine osmolality, mosM | 438.1 (168.8) | 338.7 (296.7) | 0.14 |

| Urine oxalate, mmol/24 h | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.09 |

| Urine phosphate, mg/24 h | 798.9 (390.1) | 980.3 (566.4) | 0.12 |

| Urine potassium, mmol/24 h | 59.0 (28.8) | 58.9 (31.4) | 0.90 |

| Urine sodium, mmol/24 h | 131.3 (78.8) | 178.5 (108.1) | 0.05* |

| Urine sulfate, mmol/24 h | 16.5 (7.4) | 19.3 (10.6) | 0.41 |

| Urine pH | 6.1 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.6) | 0.56 |

| Urine volume, mL | 1,991.4 (787.6) | 2,258.5 (858.2) | 0.18 |

| Urine calcium phosphate (supersaturation), dG | −0.5 (1.5) | −0.2 (1.3) | 0.56 |

| Urine uric acid (supersaturation), dG | −0.1 (2.7) | 0.2 (2.9) | 0.78 |

| Urine calcium oxalate (supersaturation), dG | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.5) | 0.22 |

| Plaque mean, %papillary surface area | 2.1 (1.4) | 9.5 (4.3) | <0.01* |

Data are presented as means (SD). CSFs, calcium oxalate stone formers; dG, ΔGibbs. Statistical differences between groups were determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical significance.

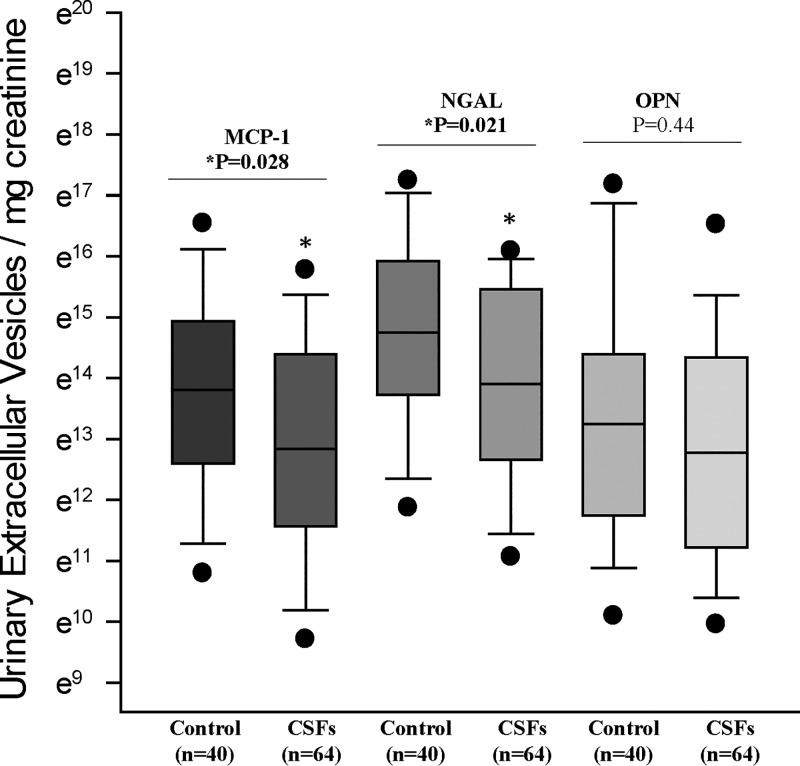

The total number of EVs expressing MCP-1 and NGAL was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in CSFs compared with nonstone formers (Fig. 2). However, the total number of OPN-positive EVs did not differ significantly between groups (Fig. 2). The total number of EVs positive for MCP-1 [44.3 (10.9, 160.2) vs. 30.9 (2.8, 250.9), P = 0.44], NGAL [119.5 (37, 536.2) vs. 91.2 (21.2, 567), P = 0.45], and OPN [35.4 (10.9, 120.2) vs. 33.3 (4.2, 385.7), P = 0.95] did not differ between low-plaque and high-plaque CSFs.

Fig. 2.

Monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1-, neutrophil gelatinase-associated protein (NGAL)-, and osteopontin-associated urinary extracellular vesicles (EVs) from idiopathic calcium oxalate stone formers (CSFs; n = 64, 33 men and 31 women) and age/sex-matched nonstone formers (n = 40, 20 men and 20 women). Data are presented as natural log (base e = 2.71828) values. Numbers of MCP-1- and NGAL-associated urinary EVs were significantly (P < 0.05) lower in CSFs compared with nonstone formers. Numbers of osteopontin-associated urinary EVs did not differ between groups.

Numbers of MCP-1-positive EVs derived from the proximal tubule, thin descending limb, and papillary duct were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in CSFs compared with nonstone formers (Table 3). Numbers of NGAL-expressing EVs derived from the proximal nephron, thin descending limb, collecting duct, and papillary duct were also significantly lower (P < 0.05) in CSFs compared with nonstone formers (Table 3). Numbers of OPN-positive EVs derived from the thin limb were nominally lower (P = 0.05) in CSFs compared with nonstone formers (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the total number of EVs associated with MCP-1, NGAL, or OPN between low- and high-RP groups (data not shown). When analyzed on the basis of the nephron segment of origin, MCP-1-expressing EVs from the thick ascending limb were nominally (P = 0.05) greater in the low-RP group compared with the high-RP group (Table 4).

Table 3.

Numbers of MCP-1-, NGAL-, and OPN-associated urinary extracellular vesicles from the different segmental epithelium of nephrons in nonstone formers (controls) and idiopathic calcium stone formers

| Segment of the Nephron | Nephron Segmental Epithelium Marker |

Tested Combination Biomarker | Nonstone Formers (n = 40) | Calcium Stone Formers | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule | URAT1 | MCP-1 | 13.2 (3.4, 44.9) | 4.6 (1, 21.1) | 0.05* |

| Ascending thin limb | Aquaporin-1 | MCP-1 | 29.2 (7.6, 96.3) | 5 (0.2, 26) | <0.01* |

| Thick limb | Uromodulin | MCP-1 | 3.7 (1.5, 19.7) | 3.4 (1, 12.2) | 0.40 |

| Distal tubule | SLC12A3 | MCP-1 | 2.1 (0.6, 10.2) | 2.8 (0.6, 11.9) | 0.96 |

| Collecting duct | Aquaporin-2 | MCP-1 | 26 (8.3, 93.5) | 16.2 (3.6, 67.3) | 0.15 |

| Papillary duct | Cytokeratin 19 | MCP-1 | 14.5 (3.2, 48.4) | 2.5 (0.7, 12.2) | <0.01* |

| Proximal tubule | URAT1 | NGAL | 19.1 (5.1, 59.2) | 8.3 (2.3, 43.8) | 0.03* |

| Ascending thin limb | Aquaporin-1 | NGAL | 50.7 (22.5, 172.5) | 8 (0.4, 54.5) | <0.01* |

| Thick limb | Uromodulin | NGAL | 62.8 (19.3, 198) | 35.4 (9.5, 130.2) | 0.13 |

| Distal tubule | SLC12A3 | NGAL | 4 (1.9, 16.1) | 4.6 (1.5, 17.2) | 0.94 |

| Collecting duct | Aquaporin-2 | NGAL | 77.3 (27, 219.4) | 38.7 (11.6, 139.5) | 0.03* |

| Papillary duct | Cytokeratin 19 | NGAL | 30.8 (5.9, 111.1) | 5.8 (1.2, 25.7) | <0.01* |

| Proximal tubule | URAT1 | OPN | 5.5 (1.6, 34.4) | 5.9 (1, 24.6) | 0.56 |

| Ascending thin limb | Aquaporin-1 | OPN | 11 (2.8, 40.8) | 4.3 (0.5, 23.3) | 0.05* |

| Thick limb | Uromodulin | OPN | 12.3 (2.5, 33) | 4.8 (1.3, 26.9) | 0.23 |

| Distal tubule | SLC12A3 | OPN | 2.7 (0.7, 15.8) | 3.8 (0.8, 17.7) | 0.76 |

| Collecting duct | Aquaporin-2 | OPN | 14.8 (3.1, 37.6) | 9.5 (2.5, 48.3) | 0.83 |

| Papillary duct | Cytokeratin 19 | OPN | 8.3 (1.6, 36.5) | 4 (0.7, 20.9) | 0.11 |

Data are presented as medians (25th percentile, 95th percentile) of the natural log of the respective marker-associated urinary extracellular vesicles/mg creatinine value. MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated protein; OPN, osteopontin; URAT1, urate transporter 1. Statistical differences between groups were analyzed with a Wilcoxon rank sum test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical significance.

Table 4.

Number of MCP-1-, NGAL-, and OPN- associated urinary extracellular vesicles from the different segmental epithelium of nephrons of idiopathic CSFs with low (<5% papillary surface area) plaque and high (≥5% papillary surface area) plaque numbers

| Segment of the Nephron | Nephron Segmental Epithelium Marker |

Tested Combination Biomarker | CSFs with Low Plaque Numbers (n = 43) |

CSFs with High Plaque Numbers (n = 21) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule | URAT1 | MCP1 | 5.9 (1.5, 21.3) | 3.5 (0.5, 27.1) | 0.58 |

| Ascending thin limb | Aquaporin-1 | MCP1 | 2.2 (0.2, 26.3) | 8.4 (0.4, 48.9) | 0.35 |

| Thick limb | Uromodulin | MCP1 | 4.4 (1.9, 12.9) | 1.3 (0.4, 8.1) | 0.05* |

| Distal tubule | SLC12A3 | MCP1 | 2.8 (0.7, 12) | 1.4 (0.2, 8) | 0.23 |

| Collecting duct | Aquaporin-2 | MCP1 | 20.1 (5.9, 67.5) | 9.9 (1.4, 70.6) | 0.19 |

| Papillary duct | Cytokeratin-19 | MCP1 | 2.4 (0.8, 11.4) | 3.4 (0.4, 46.6) | 0.78 |

| Proximal tubule | URAT1 | NGAL | 10.3 (2.7, 38.1) | 7.3 (1.8, 46.3) | 0.66 |

| Ascending thin limb | Aquaporin-1 | NGAL | 5.5 (0.3, 46) | 22.4 (1.5, 97.7) | 0.19 |

| Thick limb | Uromodulin | NGAL | 45 (11.2, 145.7) | 12.4 (4.3, 97.3) | 0.10 |

| Distal tubule | SLC12A3 | NGAL | 5 (1.6, 14.1) | 3.4 (0.9, 21) | 0.49 |

| Collecting duct | Aquaporin-2 | NGAL | 41.1 (13.8, 140.8) | 24.3 (3.9, 137.4) | 0.21 |

| Papillary duct | Cytokeratin-19 | NGAL | 4.2 (1.1, 10.8) | 13 (1.7, 50.3) | 0.13 |

| Proximal tubule | URAT1 | OPN | 7 (1.2, 17.6) | 4.4 (0.6, 49.1) | 0.91 |

| Ascending thin limb | Aquaporin-1 | OPN | 4.2 (0.4, 16.6) | 5.2 (0.7, 60.4) | 0.35 |

| Thick limb | Uromodulin | OPN | 5.4 (1.5, 17.5) | 4.1 (0.7, 133.8) | 0.97 |

| Distal tubule | SLC12A3 | OPN | 3.5 (1.2, 13.6) | 5 (0.3, 48.1) | 0.71 |

| Collecting duct | Aquaporin-2 | OPN | 9.8 (3.1, 33.3) | 8.3 (1.4, 76.1) | 0.86 |

| Papillary duct | Cytokeratin-19 | OPN | 4.2 (0.8, 13) | 3.8 (0.4, 57.1) | 0.70 |

Data are presented as medians (25th percentile, 95th percentile) of the natural log of the respective marker-associated urinary extracellular vesicles/mg creatinine value. CSFs, calcium oxalate stone formers; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated protein; OPN, osteopontin; URAT1, urate transporter 1. Statistical differences between groups were analyzed with a Wilcoxon rank sum test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Identification of causal factors and renal cellular mechanisms for calcium stone formation is necessary to develop novel treatment strategies. Our previous study demonstrated that distinct populations of nephron segment-specific urinary EVs differ between men and women, between first-time kidney stone formers and matched controls, and in relation to renal biopsy characteristics (23, 46). However, this is the first study to examine the urinary excretion of EVs associated with candidate biomarkers of inflammation (MCP-1), cell injury (NGAL), and pathological calcification (OPN) together with markers of their cell of origin in relation to stone forming status. The results indicate that EVs carrying representative inflammatory and renal cellular injury markers were significantly lower in CSFs compared with nonstone formers. However, there was no difference in the number of OPN-associated EVs by stone forming status. When examined by nephron segment of origin, EVs from the proximal nephron, descending thin limb, and papillary duct bearing MCP-1 and NGAL were significantly lower in CSFs compared with nonstone formers. Among CSFs, high-RP participants had a lower number of MCP-1- and NGAL-bearing urinary EVs, although these trends were not statistically significant. These differences in urinary EV subpopulations could reflect renal cellular responses to higher urinary calcium, CaOx crystals, and/or ongoing biomineralization. Since MCP-1- and NGAL-bearing urinary EVs were more numerous in controls and low-RP CSFs, they may reflect an adaptive response in controls that helps to prevent biomineralization events related to stone pathogenesis. It is also possible that negatively charged phosphatidylserine (annexin V positive) on the surface of EVs promotes crystal nucleation and thus consumption of EVs in the more lithogenic urine of CSFs (4, 9, 18, 27).

MCP-1 is expressed by various cells, including glomerular cells (mesangial and podocytes), renal tubular epithelial cells, and infiltrating eosinophils and mast cells (19, 28, 39). MCP-1 regulates renal inflammation and injury by selective recruitment of monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes (11, 19, 33). CaOx crystals and oxalate ions can also induce MCP-1 expression by cultured renal epithelial cells (47), and CSFs excrete greater quantities of soluble urinary MCP-1 compared with healthy controls (50). In the present study, the number of EVs expressing MCP-1 was significantly lower in CSFs compared with controls. When examined by nephron segment of origin, EVs bearing MCP-1 originating from the proximal nephron, descending thin limb, and papillary duct were significantly lower in CSFs compared with nonstone formers. The lower excretion of EVs containing MCP-1 among CSFs compared with controls, and in CSFs with high versus low percentages of RP, suggest that these specific subpopulations of EVs may contribute to stone pathogenesis by triggering or recruiting specific inflammatory cellular responses in distal nephron segments through cell-cell communication properties. Further studies are needed to confirm the exact mechanisms of EVs bearing MCP-1 involvement in calcium stone formation.

Systemic NGAL is a small (25-kDa) protein, and its production increases after acute or chronic cell injury associated with infection or inflammation and in particular with acute or chronic kidney injury (7, 36). In the present study, the number of NGAL-positive EVs was significantly lower in CSFs compared with controls. By location, EVs from the proximal nephron, descending thin limb, and papillary duct positive for NGAL were significantly lower in CSFs compared with nonstone formers. NGAL expression is induced in kidney tubular cells during regeneration after kidney injury (29). A previous study (25) has demonstrated that serum and urine levels of NGAL are not different before compared with after 10 days of unilateral shock wave lithotripsy in patients with renal calculi, whereas another study (10) has reported that urinary levels of NGAL increased 24 h after percutaneous nephrolithotripsy for stone removal compared with preoperative levels. To regulate cellular function, NGAL binds to 24p3R (a brain-type organic cation transporter) and megalin multiscavenger membrane receptors (7, 21). Both of these receptors are involved in endocytosis and cellular trafficking of NGAL alone (Apo-NGAL) and a complex with ion-binding siderophores (Holo-NGAL). Internalized Apo-NGAL captures cellular ions and exports them to the extracellular space, whereas internalized Holo-NGAL is captured inside the endosomal vesicles to release its siderophore-ion complex into the cytosol, where it activates ion-dependent specific pathways (7). The present study demonstrates that the majority of NGAL-positive EVs were derived from the collecting duct and thick limb regardless of stone forming status. The lower number of NGAL-positive urinary EVs among CSF (vs. non-stone formers) and CSFs with high RP (vs. low RP) may be due to increased accumulation within the cell at the stone forming site. Further studies are needed to identify the exact role of NGAL and its receptor expression and interactions in stone pathogenesis.

OPN (also known as uropontin) localizes to sites of pathological calcification and can inhibit CaOx and hydroxyapatite crystal growth and aggregation and block their adhesion to renal epithelial cells (5, 30, 44). All of these activities should protect against stone formation. Overall, we did not find that EV-associated OPN differed between CSF and nonstone formers. This does not mean that OPN is not important in stone pathogenesis, but it does suggest that the excretion of EV-associated OPN differs from EV-associated MCP-1 and NGAL in CSFs compared with controls. Flow cytometry can detect MCP-1, NGAL, and OPN only when present on or associated with the surface of EVs and not the free-floating (soluble) forms of these biomarkers. Therefore, the observed changes in EV-associated MCP-1, NGAL, and OPN may not reflect total excretion of these biomarkers in CSFs compared with controls.

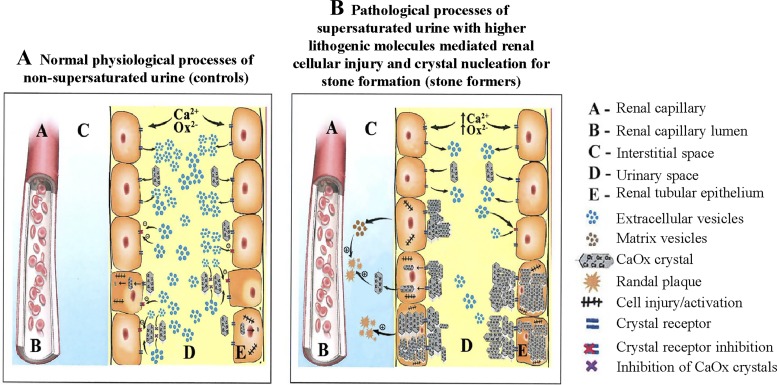

Some key observations of this study are shown in Fig. 3. Although we initially hypothesized that the number of EVs bearing MCP-1, NGAL, and OPN would be greater in CSFs, our results demonstrate the exact opposite. Thus, biomarker-bearing EVs could instead stimulate cells distally along the nephron to internalize and dissolve crystals through endosome-mediated pathways. Alternatively, specific subpopulations of EVs might signal other renal cells to decrease expression of specific cell surface molecules that can bind crystals. Lack of this inhibitory signal (i.e., fewer EVs in the urine of CSFs compared with controls) might in turn increase crystal adhesion and/or internalization and thus trigger processes that ultimately favor interstitial RP formation. Since RPs appear to begin in the basement membrane of the thin limb (16, 17, 43), it is also possible that under pathological conditions, these cells might translocate small crystals to the basement membrane and that signals transmitted by subpopulations of EVs downregulate these events.

Fig. 3.

Hypothetical interactions of supersaturated and nonsupersaturated tubular fluid and crystals with the renal tubular epithelium and/or urinary extracellular vesicles (EVs) in normal physiological (A) and pathological (B) conditions. Crystal attachment to the renal tubular epithelium in nonsupersaturated (physiological) conditions is low and the excreted number of urinary EVs is greater, whereas crystal attachment to the tubular epithelium in supersaturated (pathological) conditions is significantly greater and the number of urinary EVs is significantly lower. The resulting interstitial accumulation of crystals is greater in stone formers compared with non-stone formers. CaOx, calcium oxalate.

Another possibility is that phosphatidylserine exposed on the surface of EVs could serve as a crystalization nidus (4). The urine of CSFs is, on average, more supersaturated compared with that of nonstone formers. Furthermore, oxalate ion might promote PS exposure on the outer membrane surface (9). Thus, EVs might be more likely to promote and be consumed during crystalization events in the tubular fluid of CSFs compared with controls (18, 27).

Conclusions.

This study demonstrates that the number of urinary EVs associated with MCP-1 or NGAL is lower in CSFs compared with controls. The significance of and reason for this observation require further study. Urinary EVs are a promising source of renal cellular biomarkers that may reflect underlying stone pathogenic events. The results of this study demonstrate that reduced urinary excretion of EVs bearing inflammatory biomarkers from specific nephron segments are associated with stone forming risk and are consistent with the hypothesis that tubular fluid EVs bearing these inflammatory marker fluids might potentially mitigate stone forming risk. However, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms or pathways invoked by these EVs remains to be determined. Are the EVs responding to an increased concentration of lithogenic molecules (e.g., calcium and oxalate), crystals in the tubular lumen, or perhaps associated with other factors that associate with stone forming risk (obesity, diabetes, and hypertension)? Do the vesicles signal other types of tubular cells downstream to enhance stone pathogenesis or defense mechanisms? Do they stimulate tubular cells to release signaling molecules to the interstitium that in some way modulates the development of precursor lesions like RPs? Are selected biomarkers (MCP-1, NGAL, or OPN) present in the renal cell-derived urinary EV surface or inside of EVs or EV-free urine (soluble phase) contributing to stone pathogenesis? Does the increased lithogenicity of CSF urine lead to crystalization events on the surface of EVs that consume them? These are all speculative at this point but clearly merit further examination by in vitro and in vivo experiments.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant U54 DK-100227 from the O’Brien Urology Research Center, Rare Kidney Stone Consortium Grant U54 DK-083908, part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, an initiative of ORDR, NCATS, and NIDDK, and the Mayo Foundation.

DISCLAIMERS

The study sponsor had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.J. and J.C.L. conceived and designed research; R.S.C., S.E., Z.H., and T.M.H. performed experiments; M.J. and J.C.L. interpreted results of experiments; R.S.C., M.J., R.M., and J.C.L. analyzed data; R.S.C. and M.J. prepared figures; R.S.C. drafted manuscript; R.S.C., M.J., X.W., S.E., Z.H., M.P., T.M.H., R.M., M.E.R., and J.C.L. edited and revised manuscript; R.S.C., M.J., X.W., S.E., Z.H., M.P., T.M.H., R.M., M.E.R., and J.C.L. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abels ER, Breakefield XO. Introduction to extracellular vesicles: biogenesis, RNA cargo selection, content, release, and uptake. Cell Mol Neurobiol 36: 301–312, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0366-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agre P. Nobel lecture. Aquaporin water channels. Biosci Rep 24: 127–163, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s10540-005-2577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.An Z, Lee S, Oppenheimer H, Wesson JA, Ward MD. Attachment of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals on patterned surfaces of proteins and lipid bilayers. J Am Chem Soc 132: 13188–13190, 2010. doi: 10.1021/ja106202y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asplin JR, Arsenault D, Parks JH, Coe FL, Hoyer JR. Contribution of human uropontin to inhibition of calcium oxalate crystallization. Kidney Int 53: 194–199, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolignano D, Coppolino G, Lacquaniti A, Nicocia G, Buemi M. Pathological and prognostic value of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in macroproteinuric patients with worsening renal function. Kidney Blood Press Res 31: 274–279, 2008. doi: 10.1159/000151665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolignano D, Donato V, Coppolino G, Campo S, Buemi A, Lacquaniti A, Buemi M. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a marker of kidney damage. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 595–605, 2008. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borges FT, Reis LA, Schor N. Extracellular vesicles: structure, function, and potential clinical uses in renal diseases. Braz J Med Biol Res 46: 824–830, 2013. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao LC, Jonassen J, Honeyman TW, Scheid C. Oxalate-induced redistribution of phosphatidylserine in renal epithelial cells: implications for kidney stone disease. Am J Nephrol 21: 69–77, 2001. doi: 10.1159/000046224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daggülli M, Utangaç MM, Dede O, Bodakci MN, Hatipoglu NK, Penbegül N, Sancaktutar AA, Bozkurt Y, Söylemez H. Potential biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury after percutaneous nephrolithotripsy. Ren Fail 38: 151–156, 2016. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2015.1073494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danoff TM. Chemokines in interstitial injury. Kidney Int 53: 1807–1808, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Salahy EM. Evaluation of cytokeratin-19 & cytokeratin-20 and interleukin-6 in Egyptian bladder cancer patients. Clin Biochem 35: 607–613, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9120(02)00382-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enomoto A, Kimura H, Chairoungdua A, Shigeta Y, Jutabha P, Cha SH, Hosoyamada M, Takeda M, Sekine T, Igarashi T, Matsuo H, Kikuchi Y, Oda T, Ichida K, Hosoya T, Shimokata K, Niwa T, Kanai Y, Endou H. Molecular identification of a renal urate anion exchanger that regulates blood urate levels. Nature 417: 447–452, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nature742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evan AP, Coe FL, Lingeman J, Bledsoe S, Worcester EM. Randall’s plaque in stone formers originates in ascending thin limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1236–F1242, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00035.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Parks JH, Bledsoe SB, Shao Y, Sommer AJ, Paterson RF, Kuo R, Grynpas ML, and Grynpas M. Randall’s plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes of thin loops of Henle. J Clin Invest 111: 607–616, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI17038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fasano JM, Khan SR. Intratubular crystallization of calcium oxalate in the presence of membrane vesicles: an in vitro study. Kidney Int 59: 169–178, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haller H, Bertram A, Nadrowitz F, Menne J. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 25: 42–49, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hieda K, Hayashi S, Kim JH, Murakami G, Cho BH, Matsubara A. Spatial relationship between expression of cytokeratin-19 and that of connexin-43 in human fetal kidney. Anat Cell Biol 46: 32–38, 2013. doi: 10.5115/acb.2013.46.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hvidberg V, Jacobsen C, Strong RK, Cowland JB, Moestrup SK, Borregaard N. The endocytic receptor megalin binds the iron transporting neutrophil-gelatinase-associated lipocalin with high affinity and mediates its cellular uptake. FEBS Lett 579: 773–777, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayachandran M, Litwiller RD, Owen WG, Heit JA, Behrenbeck T, Mulvagh SL, Araoz PA, Budoff MJ, Harman SM, Miller VM. Characterization of blood borne microparticles as markers of premature coronary calcification in newly menopausal women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H931–H938, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00193.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayachandran M, Lugo G, Heiling H, Miller VM, Rule AD, Lieske JC. Extracellular vesicles in urine of women with but not without kidney stones manifest patterns similar to men: a case control study. Biol Sex Differ 6: 2, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayachandran M, Miller VM, Heit JA, Owen WG. Methodology for isolation, identification and characterization of microvesicles in peripheral blood. J Immunol Methods 375: 207–214, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kardakos IS, Volanis DI, Kalikaki A, Tzortzis VP, Serafetinides EN, Melekos MD, Delakas DS. Evaluation of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, interleukin-18, and cystatin C as molecular markers before and after unilateral shock wave lithotripsy. Urology 84: 783–788, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan SR, Canales BK. Unified theory on the pathogenesis of Randall’s plaques and plugs. Urolithiasis 43, Suppl 1: 109–123, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00240-014-0705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan SR, Maslamani SA, Atmani F, Glenton PA, Opalko FJ, Thamilselvan S, Hammett-Stabler C. Membranes and their constituents as promoters of calcium oxalate crystal formation in human urine. Calcif Tissue Int 66: 90–96, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s002230010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MJ, Tam FW. Urinary monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in renal disease. Clin Chim Acta 412: 2022–2030, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuwabara T, Mori K, Mukoyama M, Kasahara M, Yokoi H, Saito Y, Yoshioka T, Ogawa Y, Imamaki H, Kusakabe T, Ebihara K, Omata M, Satoh N, Sugawara A, Barasch J, Nakao K. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels reflect damage to glomeruli, proximal tubules, and distal nephrons. Kidney Int 75: 285–294, 2009. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieske JC, Leonard R, Toback FG. Adhesion of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals to renal epithelial cells is inhibited by specific anions. Am J Physiol 268: F604–F612, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.4.F604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maunsbach AB, Marples D, Chin E, Ning G, Bondy C, Agre P, Nielsen S. Aquaporin-1 water channel expression in human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1–14, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller NL, Gillen DL, Williams JC Jr, Evan AP, Bledsoe SB, Coe FL, Worcester EM, Matlaga BR, Munch LC, Lingeman JE. A formal test of the hypothesis that idiopathic calcium oxalate stones grow on Randall’s plaque. BJU Int 103: 966–971, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morii T, Fujita H, Narita T, Shimotomai T, Fujishima H, Yoshioka N, Imai H, Kakei M, Ito S. Association of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 with renal tubular damage in diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications 17: 11–15, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(02)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison EE, Bailey MA, Dear JW. Renal extracellular vesicles: from physiology to clinical application. J Physiol 594: 5735–5748, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP272182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nawaz M, Camussi G, Valadi H, Nazarenko I, Ekström K, Wang X, Principe S, Shah N, Ashraf NM, Fatima F, Neder L, Kislinger T. The emerging role of extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for urogenital cancers. Nat Rev Urol 11: 688–701, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paragas N, Qiu A, Hollmen M, Nickolas TL, Devarajan P, Barasch J. NGAL-siderocalin in kidney disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823: 1451–1458, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pennica D, Kohr WJ, Kuang WJ, Glaister D, Aggarwal BB, Chen EY, Goeddel DV. Identification of human uromodulin as the Tamm-Horsfall urinary glycoprotein. Science 236: 83–88, 1987. doi: 10.1126/science.3453112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pisetsky DS. Microparticles as autoantigens: making immune complexes big. Arthritis Rheum 64: 958–961, 2012. doi: 10.1002/art.34377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prodjosudjadi W, Gerritsma JS, Klar-Mohamad N, Gerritsen AF, Bruijn JA, Daha MR, van Es LA. Production and cytokine-mediated regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int 48: 1477–1486, 1995. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 200: 373–383, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riveira-Munoz E, Chang Q, Godefroid N, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Dahan K, Devuyst O; Belgian Network for Study of Gitelman Syndrome . Transcriptional and functional analyses of SLC12A3 mutations: new clues for the pathogenesis of Gitelman syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1271–1283, 2007. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sepe V, Adamo G, La Fianza A, Libetta C, Giuliano MG, Soccio G, Dal Canton A. Henle loop basement membrane as initial site for Randall plaque formation. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 706–711, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiraga H, Min W, VanDusen WJ, Clayman MD, Miner D, Terrell CH, Sherbotie JR, Foreman JW, Przysiecki C, Neilson EG. Inhibition of calcium oxalate crystal growth in vitro by uropontin: another member of the aspartic acid-rich protein superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 426–430, 1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taguchi K, Hamamoto S, Okada A, Unno R, Kamisawa H, Naiki T, Ando R, Mizuno K, Kawai N, Tozawa K, Kohri K, Yasui T. Genome-wide gene expression profiling of randall’s plaques in calcium oxalate stone formers. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 333–347, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015111271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turco AE, Lam W, Rule AD, Denic A, Lieske JC, Miller VM, Larson JJ, Kremers WK, Jayachandran M. Specific renal parenchymal-derived urinary extracellular vesicles identify age-associated structural changes in living donor kidneys. J Extracell Vesicles 5: 29642, 2016. doi: 10.3402/jev.v5.29642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Umekawa T, Chegini N, Khan SR. Oxalate ions and calcium oxalate crystals stimulate MCP-1 expression by renal epithelial cells. Kidney Int 61: 105–112, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Krambeck AE, Williams JC Jr, Tang X, Rule AD, Zhao F, Bergstralh E, Haskic Z, Edeh S, Holmes DR III, Herrera Hernandez LP, Lieske JC. Distinguishing characteristics of idiopathic calcium oxalate kidney stone formers with low amounts of Randall’s plaque. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1757–1763, 2014. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01490214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X, Lieske JC, Alexander MP, Jayachandran M, Denic A, Mathew J, Lerman LO, Kremers WK, Larson JJ, Rule AD. Tubulointerstitial fibrosis of living donor kidneys associates with urinary monocyte chemoattractant protein 1. Am J Nephrol 43: 454–459, 2016. doi: 10.1159/000446851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Sun C, Li C, Deng Y, Zeng G, Tao Z, Wang X, Guan X, Zhao Y. Urinary MCP-1、HMGB1 increased in calcium nephrolithiasis patients and the influence of hypercalciuria on the production of the two cytokines. Urolithiasis 45: 159–175, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00240-016-0902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, Colás E, Cordeiro-da Silva A, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Ghobrial IM, Giebel B, Gimona M, Graner M, Gursel I, Gursel M, Heegaard NH, Hendrix A, Kierulf P, Kokubun K, Kosanovic M, Kralj-Iglic V, Krämer-Albers EM, Laitinen S, Lässer C, Lener T, Ligeti E, Linē A, Lipps G, Llorente A, Lötvall J, Manček-Keber M, Marcilla A, Mittelbrunn M, Nazarenko I, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Nyman TA, O’Driscoll L, Olivan M, Oliveira C, Pállinger É, Del Portillo HA, Reventós J, Rigau M, Rohde E, Sammar M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Santarém N, Schallmoser K, Ostenfeld MS, Stoorvogel W, Stukelj R, Van der Grein SG, Vasconcelos MH, Wauben MH, De Wever O. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles 4: 27066, 2015. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]