Abstract

Evidence-based assessment (EBA) is foundational to high quality mental health care for youth and is a critical component of evidence-based practice delivery, yet is underused in the community. Administration time and measure cost are barriers to use; thus, identifying and disseminating brief, free, and accessible measures is critical. This Evidence Base Update evaluates the empirical literature for brief, free, and accessible measures with psychometric support to inform research and practice with youth. A systematic review using PubMed and PsycINFO identified measures in the following domains: overall mental health, anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior, traumatic stress, disordered eating, suicidality, bipolar/mania, psychosis, and substance use. To be eligible for inclusion, measures needed to be brief (50 items or less), free, accessible, and have psychometric support for their use with youth. Eligible measures were evaluated using adapted criteria established by De Los Reyes and Langer (2018) and were classified as having excellent, good, or adequate psychometric properties. A total of 672 measures were identified; 95 (14%) met inclusion criteria. Of those, 21 (22%) were “excellent,” 34 (36%) were “good,” and 40 (42%) were “adequate.” Few measures had support for their use to routinely monitor progress in therapy. Few measures with excellent psychometric support were identified for disordered eating, suicidality, psychosis, and substance use. Future research should evaluate existing measures for use with routine progress monitoring and ease of implementation in community settings. Measure development is needed for disordered eating, suicidality, psychosis, and substance use to increase availability of brief, free, accessible, and validated measures.

Keywords: evidence-based assessment, youth mental health, pragmatic measures

Evidence-based assessment (EBA) is a cornerstone of high-quality evidence-based practice in mental health care (Hunsley & Mash, 2018; Jensen-Doss, 2011; Youngstrom et al., 2017). EBA serves two key clinical functions. First, early in treatment, EBA is essential for guiding initial case conceptualization, supporting the identification of appropriate treatment targets, and guiding clinicians in the selection of evidence-based treatment strategies (Youngstrom, Choukas-Bradley, Calhoun, & Jensen-Doss, 2015). Second, after the initial assessment, EBA guides the monitoring of treatment progress and informs the personalization of treatment to optimize treatment success (Ng & Weisz, 2016; Youngstrom et al., 2015). Use of EBA both early in treatment and throughout the course of treatment (also referred to as measurement-based care; Scott & Lewis, 2015) has been associated with improved youth treatment engagement (Klein, Lavigne, & Seshadri, 2010; Pogge et al., 2001) and youth treatment response (Bickman, Kelley, Breda, de Andrade, & Riemer, 2011; Eisen, Dickey, & Sederer, 2000; Jensen-Doss & Weisz, 2008).

Use of EBA is particularly important when working with youth in routine and/or low-resource settings, such as community mental health clinics. In these settings, comorbidity is the norm (Southam-Gerow, Weisz, & Kendall, 2010; Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron, & Herren, 2013), so clinicians must adapt evidence-based treatment approaches often designed for single problem areas to suit the complex needs of their clients (Connor-Smith & Weisz, 2003). Emerging evidence suggests that a flexible treatment approach that allows for such adaptation by tailoring the sequence of treatment techniques to address individual client needs outperforms traditional manualized treatment protocols in these settings (Weisz et al., 2012). Thus, EBA may have enormous potential for supporting clinical decision-making. For example, systematic assessment signaling a possible clinical deterioration can guide clinicians’ decisions to adapt or shift treatment focus (Bearman & Weisz, 2015; Lambert, 2007; Lambert et al., 2003; Shimokawa, Lambert, & Smart, 2010).

Despite the promise of EBA in usual care for youth, use is low (Jensen-Doss & Hawley, 2010; Jensen-Doss, Becker-Haimes, et al., 2018; Whiteside, Sattler, Hathaway, & Douglas, 2016; Lyon, Dorsey, Pullmann, Silbaugh-Cowdin, & Berliner, 2015). Although multiple barriers to EBA exist (Boswell, Kraus, Miller, & Lambert 2015), surveys of practicing clinicians routinely demonstrate that the time and cost associated with engaging in EBA are most prohibitive (Kotte et al., 2016; Whiteside et al., 2016). Gold-standard diagnostic measures are costly, can take over three hours to administer (e.g., Lyneham, Abbott, & Rapee, 2007; Kaufman et al., 1997), and are typically non-billable services. They are therefore financially prohibitive, especially in publicly funded settings. Similarly, measurement and feedback systems, which provide an infrastructure for clinicians to regularly administer and interpret progress monitoring measures for youth, require substantial organizational investment that can be difficult to implement or sustain (Bickman et al., 2015; Lyon, Lewis, Boyd, Hendrix, & Liu, 2016). Although policy solutions to support insurance reimbursement for EBA have been proposed to circumvent the financial burden of these measures (Boswell et al., 2015), in the current healthcare landscape, many clinical settings cannot afford the costs associated with EBA. More research is needed on evidence-based strategies to reduce barriers to EBA implementation.

Brief, free, accessible, and validated measures to be used in EBA with youth can facilitate EBA adoption and uptake. Beidas and colleagues (2015) conducted a review of such measures for prevalent youth mental health disorders (overall mental health, anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior, eating, bipolar, suicidality, and traumatic stress). This review yielded 20 instruments that were fewer than 50 items, free, and had at least modest psychometric support for use with youth (Beidas et al., 2015). An update and extension to this review is needed. First, the initial review primarily served as a clinical guide and reference for selecting measures and did not emphasize their psychometric properties. A comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric properties for identified measures is needed to inform our understanding of the current state of the science and to set an agenda for future research. Second, since the publication of this initial review, multiple repositories designed to house freely accessible measures were created, there has been an increased emphasis on developing pragmatic measures to be used in EBA (Jensen-Doss, 2015), and implementation efforts focused on EBA for youth are underway (e.g., Lyon et al., 2017; Jensen-Doss, Ehrenreich-May et al., 2018). Related, the initial search was conducted prior to the publication of DSM-5 (American Psychological Association, 2013); in the past several years, new measures may have been developed to match updated diagnostic criteria and new diagnostic categories (e.g., avoidant/restrictive food intake, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder). Finally, the original review did not include any measures related to assessment of substance use. Given the growing public health crisis related to substance abuse in adolescence (Degenhardt et al., 2016), it is important to extend the initial review to cover measures of youth substance use.

This systematic review provides a comprehensive Evidence Base Update for brief, free, and accessible EBA measures for use in youth mental health, guided by criteria set forth by De Los Reyes and Langer (2018; see Table 1). The primary objectives of this review are to provide (a) an overview of the state of the science for currently available brief, free, and accessible measures, (b) recommendations for areas of priority for future research, and (c) an expanded clinical resource for those seeking to implement EBA in community settings. We paid particular attention to evaluating measures with regard to their psychometric properties to routinely monitor treatment progress, in addition to reliability and validity, since mental health care is increasingly moving toward requiring clinicians and organizations to demonstrate the quality of care provided.

Table 1.

Rubric for Evaluating Norms, Validity, and Utility

| Criterion | Adequate | Good | Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norms | M and SD for total score (and subscores if relevant) from a large, relevant clinical sample | M and SD for total score (and subscores if relevant) from multiple large, relevant samples, at least one clinical and one nonclinical | Same as “good,” but must be from representative sample (i.e., random sampling, or matching to census data) |

| Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha, Split Half, etc.) | Most evidence shows alpha values of 0.70–0.79 | Most reported alphas 0.80–0.89 | Most reported alphas ≥ 0.90 |

| Interrater Reliability | Most evidence shows kappas of 0.60–0.74, or intraclass correlations of 0.70–0.79 | Most reported kappas of 0.75–0.84, ICCs of 0.80–0.89 | Most kappas ≥ 0.85, or ICCs ≥ 0.90 |

| Test–Retest Reliability (Stability) | Most evidence shows test–retest correlations ≥ 0.70 over several days or weeks |

Most evidence shows test–retest correlations ≥ 0.70 over several months |

Most evidence shows test–retest correlations ≥ 0.70 over 1 year or longer |

| Repeatability | Bland–Altman (Bland & Altman, 1986) plots show small bias, and/or weak trends; coefficient of repeatability is tolerable compared to clinical benchmarks (Vaz et al., 2013) | Bland–Altman plots and corresponding regressions show no significant bias, and no significant trends; coefficient of repeatability is tolerable | Bland–Altman plots and corresponding regressions show no significant bias, and no significant trends; established for multiple studies; coefficient of repeatability is small enough that it is not clinically concerning |

| Content Validity | Test developers clearly defined domain and ensured representation of entire set of facets | Same as “adequate,” plus all elements (items, instructions) evaluated by judges (experts or pilot participants) |

Same as “good,” plus multiple groups of judges and quantitative ratings |

| Construct Validity (e.g., Predictive, Concurrent, Convergent, and Discriminant Validity) | Some independently replicated evidence of construct validity | Bulk of independently replicated evidence shows multiple aspects of construct validity | Same as “good,” plus evidence of incremental validity with respect to other clinical data |

| Discriminative Validity | Statistically significant discrimination in multiple samples; AUCs < 0.6 under clinically realistic conditions (i.e., not comparing treatment seeking and healthy youth) | AUCs of 0.60 to < 0.75 under clinically realistic conditions | AUCs of 0.75 to 0.90 under clinically realistic conditions |

| Prescriptive Validity | Statistically significant accuracy at identifying a diagnosis with a well-specified matching intervention, or statistically significant moderator of treatment | Same as “adequate,” with good kappa for diagnosis, or significant treatment moderation in more than one sample | Same as “good,” with good kappa for diagnosis in more than one sample, or moderate effect size for treatment moderation |

| Validity Generalization | Some evidence supports use with either more than one specific demographic group or in more than one setting | Bulk of evidence supports use with either more than one specific demographic group or in multiple settings | Bulk of evidence supports use with either more than one specific demographic group AND in multiple settings |

| Treatment Sensitivity | Some evidence of sensitivity to change over course of treatment | Independent replications show evidence of sensitivity to change over course of treatment | Same as “good,” plus sensitive to change across different types of treatments |

| Clinical Utility | After practical considerations (e.g., costs, respondent burden, ease of administration and scoring, availability of relevant benchmark scores, patient acceptability), assessment data are likely to be clinically actionable | Same as “adequate,” plus published evidence that using the assessment data confers clinical benefit (e.g., better outcome, lower attrition, greater satisfaction), in areas important to stakeholders | Same as “good,” plus independent replication |

Note. Rubric initially developed by Hunsley and Mash (2008) and extended by Youngstrom et al. (2017). Evaluation criteria were adapted in this study due to the large number of measure that met inclusion criteria for review. Table reproduced with permission from De Los Reyes and Langer (2018).

Methods

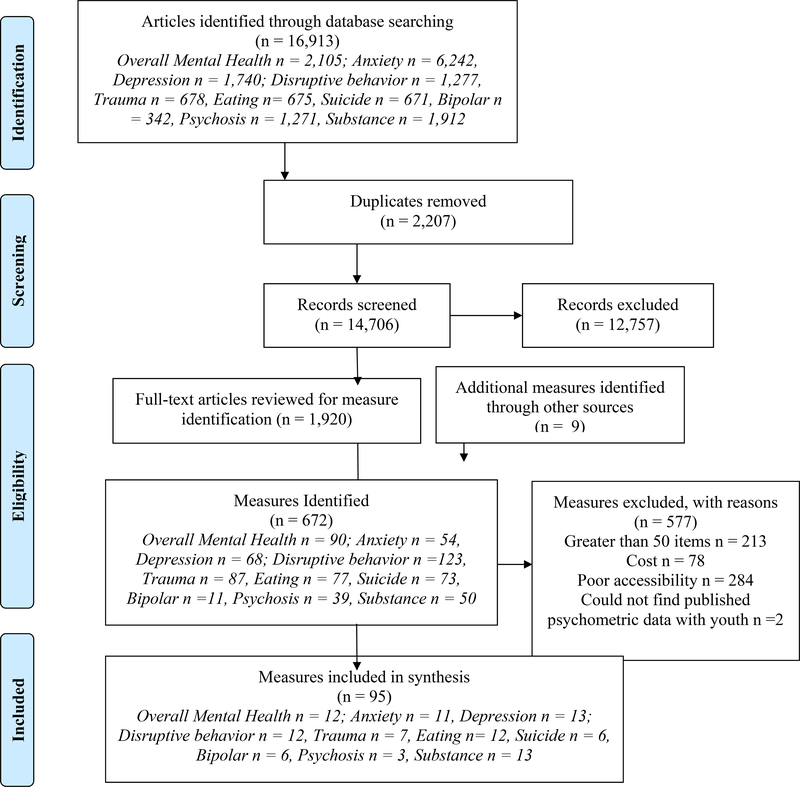

Our review process built on procedures used by Beidas and colleagues (2015) in their initial review, which was conducted in 2012–2013. Search criteria were expanded and updated to include DSM-5 language. We employed a more rigorous three-stage systematic review process that included: 1) measure identification, 2) measure eligibility assessment, and 3) evaluation of measure psychometric properties. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Measure Identification

We searched PubMed and PsycINFO in October, 2018 using the following search terms: (“disorder name/type”) AND (“instrument” OR “survey” OR “questionnaire” OR “measure” OR “assessment”) AND (“psychometric or “measure development” or “measure validation”). Each disorder name/type was searched individually, using the following terms: overall mental health: (“mental health” OR “behavioral health” AND “internalizing” OR “externalizing”); anxiety: (“anxiety” OR “obsessive-compulsive disorder” OR “panic” OR “worry” OR “generalized anxiety disorder” OR “stress” OR “phobia”); depression: (“depress*” OR “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder”); disruptive behavior disorders: (“conduct disorder” OR “oppositional defiant disorder” OR “attention-deficit” OR “disruptive behavior”); traumatic stress: (“traum*” OR “traum* exposure” OR “post-traumatic stress” OR “acute stress”); eating: (“eating disorder” OR “anorexia nervosa” OR “bulimia nervosa” OR “avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder” OR “binge eating” OR “picky eating”); suicide: (“suicide” OR “suicidality” OR “self-injurious”); bipolar: (“bipolar” OR “mania”); psychosis: (“schizophrenia” OR “psychosis” OR “psychotic”); substance use: “substance abuse” OR “substance use” OR “alcohol” OR “opioid” OR “tobacco” OR “nicotine” OR “marijuana” OR “cannabis”). We also conducted a hand-search for measures in three textbooks on youth EBA: Assessment of Childhood Disorders, Fourth Edition (Mash & Barkley, 2007), A Guide to Assessments that Work, Second Edition (Hunsley & Mash, 2018) and Diagnostic and Behavioral Assessment in Children and Adolescents: A Clinical Guide (McLeod, Jensen-Doss, & Ollendick, 2013).

This initial search returned 16,913 articles. Abstracts were screened for relevance by members of the authorship team (EBH, AT, BL, and RS). Articles were classified as “relevant” if they included a measure with a clearly defined youth sample (i.e., 18 or under) or were a review of measures for youth. Articles in this stage were excluded if they were clearly about diagnostic interviews, were not in English, or referenced a construct not of interest for this review (e.g., personality assessment). The team initially met and coded a subset of articles as a group (n = 20) and achieved perfect reliability. The remaining articles were therefore screened independently and the team met weekly to discuss any concerns and come to consensus when a coder was uncertain regarding the relevance of an abstract. A total of 1,920 articles were classified as relevant. These articles were subjected to full-text review in which the names of measures used in each article were extracted for the second phase of review; 663 measures were identified across the 1,920 articles included in this full-text review and were screened for eligibility inclusion criteria. The textbook search returned nine measures beyond the 663 obtained via literature search, for a total of 672 measures, lending support for the breadth of our search terms

Measure Eligibility

Measures were required to meet four inclusion criteria to be eligible. Specifically, measures had to: 1) be brief (i.e., defined as 50 items or fewer, including sub-items), 2) be free (i.e., no associated cost for individual use), 3) be accessible (i.e., easily obtainable in ready-to-use format on the Internet), and 4) have available data for their psychometric properties for youth. To meet the “free” criterion, measures must have included a statement that the measure was available for individual use without charge. Measures did not have to be in the public domain to meet our criteria; thus, some identified measures are unalterable and may be subject to cost or institutional agreement if used by an organization. Of note, we excluded a subset of measures that met “brief” criteria that were freely available on the Internet in violation of copyright laws at the time of our search or could not be verified as freely available. To be considered “accessible,” the measure needed to be in a “ready-to-use” format (e.g., a list of measure items in a public-access journal article was not considered accessible, as it would require a clinician to reformat items in a separate document to add instructions and a rating scale).

Of the 672 measures initially identified, a subset of measures were excluded for: length (n = 213), cost (n = 78), and poor accessibility (n = 284). Two additional measures were excluded because we were unable to find any published psychometric data in a youth sample. Our final sample constituted 95 measures.

Measure Psychometrics

Psychometric review was guided by criteria set forth by De Los Reyes and Langer (2018). Given the number of measures identified, conducting a full psychometric review for each individual measure was not feasible. A subset of the identified measures have been subject to full systematic reviews of their psychometric properties (e.g., the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; Kersten et al., 2016) or have publicly available instrument manuals. Whenever possible, we independently reviewed each measure’s psychometrics based on these existing reviews. When summative statements were not available (which was the norm), we examined psychometrics as reported both in the source manuscript for the measure and papers citing the source manuscript that focused on youth samples, using the “cited by” feature in Google Scholar (i.e., a “citation searching” approach to review; Wright, Golder, & Rodriguez-Lopez, 2014). Each measure was reviewed and classified as either having excellent, good, or adequate psychometric properties, consistent with the categories recommended by De Los Reyes and Langer (2018).

Measures were classified as “excellent” if we were able to locate two or more separate psychometric studies that showed evidence of: internal consistency > .9, test-retest > .7, some norms (e.g., M and SD for a large, relevant clinical sample), validity in at least two categories (e.g., convergent and discriminant), and treatment sensitivity (unless a screening measure). A measure could be classified as “good” in one of two ways: (1) if the measure met all of the psychometric properties outlined above under the “excellent” criteria, but we were only able to locate one study, or (2) if multiple studies demonstrated psychometric properties consistent with the criteria put forth by De Los Reyes and Langer for “good” measures (e.g., internal consistency values of .8-.9), evidence of at least one form of validity, minimal normative data, and at least some evidence for treatment sensitivity or test-retest reliability. We classified measures as “adequate” if the measure had some evidence of reliability or validity from one or more studies, but data were inconsistent (e.g., psychometric properties varied based on sample), limited (e.g., absence of normative data, no test-retest reliability data), or questionable (e.g., internal consistency values below .75). As we were unable to conduct a nuanced evaluation of validity, it is important to note that this adaptation of De Los Reyes and Langer’s criteria likely resulted in less conservative definitions of “excellent” and “good” psychometric strength, with measures more easily being categorized as excellent than if measures had been subjected to a full review. We also did not conduct reviews of measure interrater reliability, or repeatability. Twenty-two measures (23%) were randomly selected across the diagnostic categories for double coding and yielded excellent reliability (kappa = .79; Cicchetti, 1994).

Results

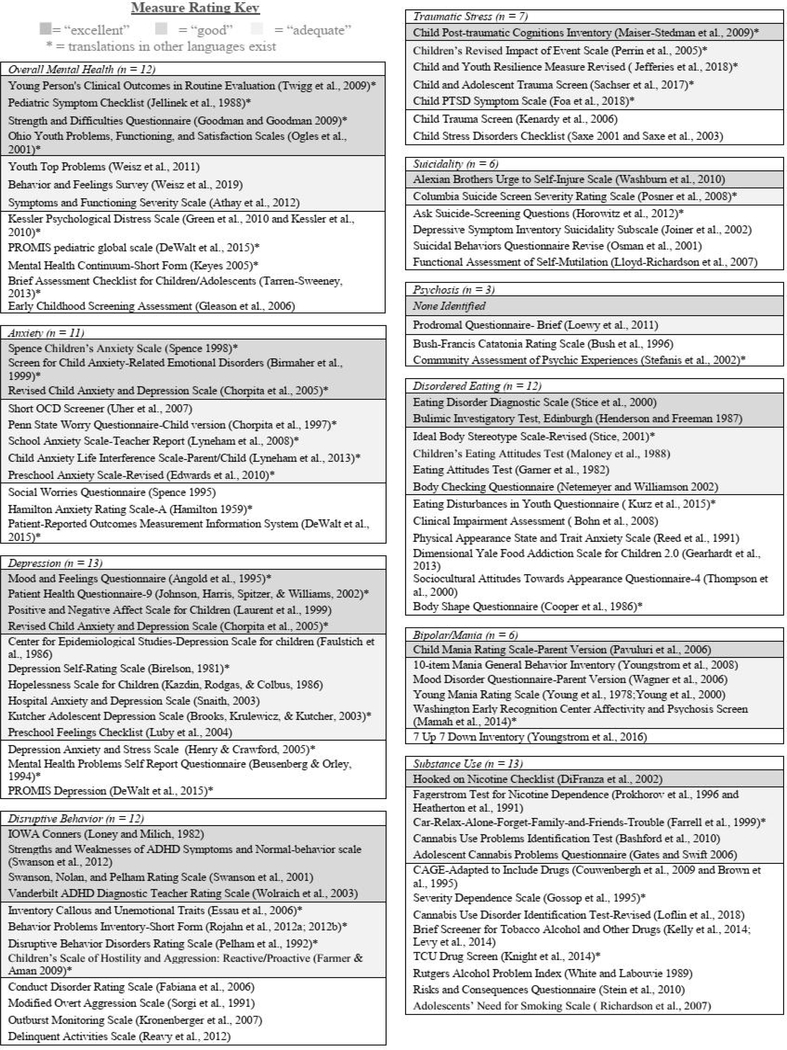

Supplemental tables 1–10 display the following information for all identified measures: overall psychometric rating (i.e., excellent, good, or adequate), number of items, available forms (self, parent, clinician, or teacher report), intended age range for use, intended clinical use (screening, diagnostic aid/treatment planning, or progress monitoring), evidence of treatment sensitivity, and a link to the measure. We also denote which measures have freely available translations in other languages. Figure 2 illustrates an overview of all identified measures. A brief summary of the findings is below, by diagnostic category.

Figure 2.

Measures at a Glance: Brief, Free, Accessible Youth Mental Health Measures

Overall Mental Health

Twelve of 90 identified measures of overall mental health met inclusion criteria (13%; Supplemental Table 1). Measures ranged from 6 to 48 items and covered youths age 1.5 to 18+ years old. In general, measures had strong psychometric properties, with four measures rated as having “excellent” psychometric support. Measures with excellent support included the Young Person’s Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (Twigg et al., 2009), the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (Jellinek et al., 1988), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman & Goodman, 2009), and the Ohio scales (Ogles et al, 2001). Three measures were rated as “good.” Five were rated as “adequate.”

Except for the Youth Top Problems Assessment (Weisz et al., 2011), all identified measures were standardized instruments assessing internalizing, externalizing, or general mental distress symptoms. Nine measures could be used for screening and/or aiding in diagnosis/treatment planning; eight were also intended for use with progress monitoring. Most measures had at least minimum evidence for internal consistency and construct validity; fewer had information about test-retest reliability, incremental validity, or treatment sensitivity. Five measures had support for their use for routine progress monitoring (at least monthly administration): the Ohio Youth Problems, Functioning, and Satisfaction Scales, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; the Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale, the Behavior and Feelings Survey, and the Youth Top Problems; the latter three had support for their use on a weekly basis.

Anxiety

Eleven of 54 measures of anxiety met inclusion criteria for review (19%; Supplemental Table 2). Measures ranged from 7 to 47 items and provided coverage for youth ages 3 to 18+. Three measures were rated as having “excellent” psychometric properties and included the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence, 1998), the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999), and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al., 2005). Five measures were rated as “good.” Three were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were designed to either screen for anxiety disorders and/or aid the diagnostic and treatment planning process with the exception of two, the PROMIS Anxiety (DeWalt et al., 2015) and the Short OCD Screener (Uher et al., 2007), which were designed specifically for screening in time-limited settings (e.g., primary care). Six measures were also intended for progress monitoring. Most measures rated as either “good” or “excellent” had support for their content, construct, and discriminant validity, but there was little information about the incremental validity of any measure. Only four measures had evidence of any treatment sensitivity: The Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale, RCADS, SCARED, and the SCAS. However, treatment sensitivity data were mixed and unclear as to the appropriate frequency with which these measures should be optimally administered for progress monitoring.

Depression

Thirteen of 68 measures of depressive (or mood) symptoms met inclusion criteria (19%; Supplemental Table 3). Measures ranged from 6 to 47 items and covered youth from the ages of 3 to 18+. Four measures met “excellent” criteria for psychometric properties: the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ; Angold et al., 1995), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Johnson et al., 2002), the Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children (PANAS-C; Laurent et al., 1999), and the RCADS (Chorpita et al., 2005).1 Six measures were rated as “good.” Three were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were intended to be used for screening or aiding in diagnosis, with eight also intended for progress monitoring. All the measures rated as “good” or “excellent” had strong support for their reliability and validity and at least some evidence for their treatment sensitivity. However, treatment sensitivity data were primarily evidenced by pre- and post-treatment data in clinical trials; we identified little support for the use of any of the identified depression measures for routine progress monitoring with youth.

Disruptive Behavior

Twelve of 123 measures of disruptive behavior problems met inclusion criteria (10%; Supplemental Table 4). Measures ranged from 10 to 48 items and covered youth ages 2 to 18+. Four measures were classified as having “excellent” psychometric support: the IOWA Conners (Loney and Milich, 1982), the Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal-behavior scale (SWAN; Swanson et al., 2012), the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale (SNAP-IV; Swanson et al., 2001), and the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale (VADTRS; Wolraich et al., 2003). Four measures were rated as “good.” Four were rated as “adequate.”

The intended use of measures of disruptive behavior problems represented a range of screening, diagnostic aid, and progress monitoring tools. Some measures, such as the VADTRS, SNAP-IV, the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBDRS; Pelham et al., 1992), and the Conduct Disorder Rating Scale (Waschbusch et al., 2007) closely map on to DSM criteria and thus function as standalone diagnostic instruments for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, or Conduct Disorder. Others are intended to assess disruptive or aggressive behavior more broadly to inform treatment planning and progress monitoring (e.g., the Inventory of Callous and Unemotional Traits; Essau et al., 2006). Although only five measures were intended for use as progress monitoring measures, eight had at least minimal evidence for their treatment sensitivity. Nearly all evidence for treatment sensitivity came from treatment trials where measures were administered pre- and post-treatment only. We identified little evidence for the use of any identified measures for routine progress monitoring with youth.

Traumatic Stress

Seven of 87 measures of traumatic stress met inclusion criteria (9%; Supplemental Table 5). Measures ranged from 8–36 items and covered youths age 2 to 18+. Only one measure met criteria for “excellent” psychometric support: the Child Post Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (CPTCI; Maiser-Stedman et al., 2009). Four measures were rated as “good.” Two were rated as “adequate.”

Overall, measures of traumatic-stress were primarily intended for use as screening tools or diagnostic aids. No measures were designed for progress monitoring, although five had at least some support for their treatment sensitivity as measured pre- and post-treatment: the CPTCI, the Child and Youth Resilience Measure Revised (CYRM; Jefferies et al., 2018), the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS; Sachser et al., 2017), Child Stress Disorders Checklist (CSDC; Saxe, 2001), and the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES; Perrin et al., 2005). Of note, three measures represented recent revisions or new measures, most likely in light of changed diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV to DSM-5. These measures (the CYRM, the CATS, and the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 [CPSS-5; Foa et al., 2018]) were classified as “good” solely because they had only one published study on their psychometric properties for the revised measure at the time of review, but may be classified as “excellent” as more studies with DSM-5 criteria are published.

Eating Disorders

Twelve of 77 measures of disordered eating met inclusion criteria (16%; Supplemental Table 6). Measures ranged from 6 to 40 items and were intended for use primarily with adolescents, although several had some psychometric data for their use with youth as young as six years old. Two measures, the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; Stice et al., 2000) and the Bulimic Investigatory Test (BITE; Henderson & Freeman, 1987) met criteria for excellent support. Four measures were rated as “good.” Six were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were intended for use as screening tools or diagnostic aids, with three also intended for progress monitoring. Most represented downward extensions of measures with ample psychometric support for their use with undergraduate or adult samples but either had limited psychometric data to support their use with youth or have demonstrated inconsistent or unstable factor structures when applied to adolescent samples. Five measures were shown to have at least minimal treatment sensitivity (i.e., evidence of change from “pre” to “post” treatment) in a youth or adolescent sample: the EDDS, the BITE, the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT; Maloney et al., 1988), the Body Checking Questionnaire (BCQ; Netemeyer & Williamson 2002), and the Ideal Body Stereotype Scale-Revised (IBSS-R; Stice, 2001). Only the BITE had support for its use beyond pre- and post-treatment and can be used on a monthly basis.

Suicidality

Six of 73 measures of suicidality met inclusion criteria (8%; Supplemental Table 7). Measures ranged from 4 to 40 items and covered youths aged 5 and up, although most measures were designed for use with adolescents only. Only one measure was classified as “excellent” with respect to its psychometrics: the Alexian Brothers Urge to Self-Injure Scale (ABUSI; Washburn et al., 2010). One measure was rated as “good.” Four were rated as “adequate.”

Identified measures of suicidality were designed for screening and/or risk assessment, with the exceptions of the ABUSI and the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2007), which were designed primarily to inform treatment or safety planning. With the exceptions of the Columbia Suicide Screen Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2008), which was classified as having “good” support for its use with youth, and the ABUSI, identified measures had limited or inconsistent published psychometric data to support their use. Only the ABUSI and C-SSRS had any data to support their treatment sensitivity; the ABUSI has support for its use pre- and post-treatment only, while the C-SSRS has demonstrated sensitivity to change over a six-week period. No measure had support for its use as a routine progress monitoring tool.

Bipolar/Mania

Six of 11 measures of bipolar or manic symptoms met inclusion criteria (55%; Supplemental Table 8). Measures ranged from 10 to 21 items and were intended for youths aged 5 to 18+. Only one measure, the Child Mania Rating Scale-Parent Version (CMRS-P; Pavuluri et al., 2006), met criteria for excellent psychometric properties. Four measures were rated as “good.” One was rated as “adequate.”

All identified measures were intended as screening tools or diagnostic aids; two were also intended for use with progress monitoring. Overall, measures had adequate support for their internal consistency, convergent, and discriminant validity, although evidence for test-retest reliability and treatment sensitivity were more limited. The CMRS-P and YMRS were the only identified measures with evidence for treatment sensitivity. The CMRS-P can be administered weekly for progress monitoring.

Psychosis

Three of 39 measures of psychosis met inclusion criteria (8%; Supplemental Table 9). Measures ranged from 21 to 42 items. All three measures were intended for adolescents aged 12 and up and were designed to be used primarily for screening. No measure was rated as having “excellent” psychometric properties. Only one measure was classified as “good” with respect to psychometric properties, the Prodromal Questionnaire Brief (Loewy et al., 2011), which showed good internal consistency and concurrent and predictive validity but lacked data on test-retest reliability and treatment sensitivity. Two measures were classified as “adequate.” There was no evidence for test-retest reliability or treatment sensitivity for any identified measure to support its use as a progress monitoring tool with youth.

Substance Use

Thirteen of 50 measures of substance use/abuse met inclusion criteria (26%; Supplemental Table 10). Measures ranged from 4 to 35 items and were intended for individuals ages 12 and up. Only one measure, the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC; DiFranza et al., 2002) met criteria for “excellent” psychometric properties. Four measures were rated as “good.” Eight were rated as “adequate.”

All measures were intended as screening tools or to support the diagnostic process; two were also intended for use with progress monitoring. Identified substance use measures varied as to whether they represented broad or specific measures of substance use. Six measures were designed to measure substance use broadly, three specifically assessed nicotine addiction, three assessed cannabis use/abuse, and one measure focused on alcohol. Seven measures were designed as screening tools only and represented downward extensions of measures developed with undergraduate or adult samples and had limited psychometric data for their use with adolescent samples. Only two measures had marginal support for their treatment sensitivity (pre-treatment to six months later): the HONC and the Cannabis Use Problems Identification Test (CUPIT; Bashford, Flett, & Copeland, 2010). No measure had any psychometric evidence for its utility as a progress monitoring tool with youth.

Discussion

This systematic review offers the most comprehensive information available on the psychometric properties of brief, free, and accessible clinical measures for youth mental health. The measures described represent the current state of the science for pragmatic EBA measures and can also serve as an expanded reference to inform selection and use of EBA measures in routine and low-resource clinical settings. Our review identified over 600 measures of youth mental health symptoms, yet relatively few (14%, n = 95) were pragmatic tools that may be easily implemented in the community. We identified nearly five times the number of brief, free, accessible, and validated measures than the initial review conducted by Beidas and colleagues (2015). Existing measures generally covered a wide age range (2 to 18+) and, with the exception of psychosis measures, all diagnostic areas had at least one measure classified as having excellent psychometric support. However, only a small subset of available measures (3%, n = 21) were classified as having “excellent” psychometric properties - even with less conservative evaluative criteria than those delineated by De Los Reyes and Langer (2018). There were notable gaps in the availability of brief, free, accessible, and validated youth measures for disordered eating, suicide, psychosis, and substance use. Furthermore, even among measures with relatively strong reliability and validity data that we classified as having excellent psychometric properties, treatment sensitivity data were limited; only seven measures (1%) across all of the examined diagnostic categories had treatment sensitivity data to support monthly administration for routine progress monitoring. As more frequent administration of measures may be needed to inform clinical decision making with respect to treatment sequencing and personalization, this suggests a major weakness in the current literature.

Taken together, results suggest more work is needed to advance the science of pragmatic measures to be used in EBA for youth mental health. Future research should focus on developing pragmatic measures that can be used to monitor treatment progress and evaluating their psychometric properties in the settings where youth are most likely to receive treatment (e.g., community mental health clinics, schools, primary care offices). Below, we delineate several important next steps to achieve this aim and to increase the likelihood that EBA will be implemented in diverse community settings.

Measure Development

Our review highlights several key areas for measure development. First, there is a dearth of well-validated measures in key areas of public health concern in youth: disordered eating, suicidality, psychosis, and substance use. There is an urgent need to develop new measures or improve existing measures to adequately assess these areas. Measures should be developed specifically for youth and adolescent needs, rather than as downward extensions of adult measures. As can be seen in Supplemental Tables 6, 7, 9, and 10, many of the identified measures in these areas rely primarily on youth self-report. Thus, new measures should be designed to be completed by multiple informants (e.g., youth and caregivers). Second, only one of our 95 identified measures was an idiographic, or individualized, assessment measure (the Youth Top Problems; Weisz et al., 2011). There is evidence that practicing clinicians view idiographic assessment tools more positively and use them more often than standardized assessment tools (Jensen-Doss, Smith et al., 2018). Thus, future measure development should focus on developing pragmatic, individualized assessment measures that can be used to support the delivery of evidence-based treatments. Third, to enhance the likelihood that measures will be readily implemented in community settings, we recommend that future research consider a community-partnered approach to measure development. Involving practicing clinicians and other stakeholders (e.g., agency leaders, clients) in the design and evaluation of new youth measures could ensure that the measure will be viewed as acceptable, feasible, and clinically informative for use in community settings.

Treatment Sensitivity and Clinical Utility in Measure Development

Our review indicates there is a need for greater attention to evaluating the treatment sensitivity of measures to inform their use in routine progress monitoring in future research. This could be done in several ways and begs the question of whether new measures should be developed to specifically monitor treatment progress or whether existing freely available measures should be further studied. One possible low-cost way to examine the utility of current measures for progress monitoring is to mine existing clinical trials datasets that administered many assessment measures at frequent time points over the course of youth treatment (e.g., Walkup et al., 2008). As noted above, development and evaluation of new measures to monitor treatment progress would ideally be done in collaboration with key stakeholders in community settings.

Evaluate Psychometric Properties of Measures in Community Settings

Research is needed that explicitly focuses on the performance of youth measures in routine clinical settings. Just as evidence-based treatments often show reduced effect sizes when delivered in the community (Weisz, Ng, & Bearman, 2014), measures may not perform comparably psychometrically when applied to youth presenting in settings such as community mental health or primary care (Youngstrom, Meyers, Youngstrom, Calabrese, and Findling, 2006). Future meta-analytic work examining psychometric performance of brief measures might also consider coding for the setting and population features to test whether setting characteristics moderate psychometric performance.

Comparative trials of the psychometric properties of established youth measures within problem areas in these settings are also needed to inform EBA implementation efforts. Currently, there is little empirical data to guide decision making for the use of one measure over another. Comparative trials examining the utility of specific batteries of pragmatic measures across multiple problem areas are also needed. In particular, it would be useful for future studies to test the reliability, validity, and utility of a collection of brief screeners or diagnostic aids. Such a battery could then be tested relative to gold-standard diagnostic interviews to determine whether the lengthier and often more costly interviews provide incremental utility over a carefully curated set of pragmatic questionnaires. This could shed light on how to best implement EBA in community settings, given time and resource constraints.

Develop Criteria for Assessing Measures for EBA Implementation Readiness

An important next step in evaluating pragmatic measures to be used in EBA is to add dimensions related to their acceptability and feasibility of implementation. As noted above, clinicians report varying levels of acceptability for different measures (e.g., standardized vs. individualized assessment; Jensen-Doss, Smith et al., 2018). A measure’s brevity does not indicate that it is easy to administer, score, and interpret. For example, some measures (e.g., the RCADS) provide freely available tools to assist clinicians with scoring and interpretation, but many do not. Future research should examine the acceptability and feasibility of measures from the perspectives of key stakeholders such as consumers, clinicians and organizational leadership. Such work could help select specific measures most likely to have buy-in and be sustainably implemented.

It is worth noting that, through the course of our review, we identified the existence of multiple repositories designed to house measures (See Supplementary Materials 2 for an overview of identified repositories) as well as several additional repositories that are under development. The growth of these repositories likely contributed to our identification of a significantly greater number of freely available measures than the initial review conducted by Beidas and colleagues (2015). However, the measures contained in each repository often did not overlap and were not always updated with the latest versions of the measure. Repositories varied in how they selected measures to include; some required authors to self-submit and self-report on the measure’s psychometric evidence, others gathered experts to recommend measures for inclusion. The dynamic nature of these repositories suggests that the landscape of freely available measures may shift quickly; however, in the absence of a single, coordinated effort to house pragmatic measures, these repositories are unlikely to keep pace with advancing science.

Results should be taken in the context of limitations. First, while we tried to be as comprehensive as possible in our review, it is possible additional measures exist that were not identified through out literature search. Future reviews might expand search methods to include screening published practice parameters for assessment and meta-analyses of published measures (e.g., by crossing the disorder-specific search terms with “AND meta-analysis”). Most notably, we did not conduct a formal systematic review of the psychometric properties for each of the measures within each of the De Los Reyes and Langer (2018) categories and instead employed a “citation searching” approach to review. Thus, it is possible that some of our measures had additional psychometric support beyond what is reported here; this may be particularly true for measures that have multiple “primary source” citations. As previously noted, our adapted evaluation criteria likely resulted in an overestimation of the strength of the psychometric support for certain measures. However, given the relatively few measures identified as having excellent psychometric properties, we do not feel a more conservative application of psychometric review criteria would have substantially changed our recommendations for future research. Related, we note that the De Los Reyes and Langer (2018) criterion for internal consistency values may be in conflict with our focus on brief measures, as typical interpretation of Cronbach’s alpha values may not be the appropriate approach for very short scales (Streiner and Kottner, 2014). Future reviews should consider alternative review criteria for ultra-brief measures, such as average inter-item values or use of a “sliding scale” for alpha values commensurate with scale length (e.g., .90 remains the criterion for “excellent” support for items with 20 or more items, but lower values are used to establish “excellent” support for shorter scales) and reducing the weight placed on alpha values for measure classifications (Youngstrom, Salcedo, Frazier, & Perez Algorta, 2019).

We also focused our review primarily on symptoms for a range of presenting youth mental health concerns; other measures may of interest to community clinicians (e.g., functioning, quality of life) or of clinical use with respect to progress monitoring to track target mechanisms of treatment (e.g., emotion regulation, social skills, family accommodation, parenting practices, intolerance of uncertainty), particularly as the field’s understanding of key treatment mechanisms continues to develop (McKay, 2019). These constructs may be targeted in future reviews. Given the number of measures identified, and the vast and complex literature regarding informant agreement for youth (De Los Reyes et al., 2015), we also did not conduct a review of measure interrater reliability (i.e., correlations between parent, youth, and teacher report). However, as emerging evidence suggests informant disagreement can be used to inform monitoring of treatment progress (Becker-Haimes, Jensen-Doss, Birmaher, Kendall, & Ginsburg, 2018; Goolsby et al., 2018), a future review may focus specifically on informant agreement for brief, free, and accessible measures. Finally, an additional challenge that emerged in our review concerned how to review measures that represented revisions to reflect new diagnostic criteria (e.g., the CPSS updated to reflect DSM-5 criteria). In the absence of established criteria, we elected to review the properties of the revised measure as its own entity. Future work should establish clear criteria for evaluating revised measures in which there is substantial psychometric evaluation of the original measure.

This review also has notable strengths. We employed a rigorous review process to identify and evaluate a broad range of youth measures to be used in EBA; many measures have been evaluated in so many studies as to warrant possible Evidence Base Updates on their own. Our emphasis on examining the treatment sensitivity of EBA measures fills a critical gap in current evidence-based assessment reviews, particularly with increased moves to implement EBA in routine community settings and increasing efforts across the field to tie payment to outcomes and quality metrics (such as in value-based purchasing; Kilbourne et al., 2018) and highlights the need for more work developing free, brief, and accessible measures with adequate treatment sensitivity for use in progress monitoring in community settings.

Conclusions

There is much to be done with respect to the development, evaluation, and implementation of measures for youth mental health to be used in EBA efforts. Our review identified measures that can be freely used by community clinicians. However, there are limited options for clinicians when it comes to selecting measures to monitor treatment progress. More research is needed to expand upon existing measures and improve our understanding of the feasibility of implementing these measures in diverse clinical contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The research was supported in part by NIMH P50113840 (PIs: R Beidas, D Mandell, K Volpp). B.S. Last was also supported by the National Science Foundation, Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-1321851). R.E. Stewart was also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [K23DA048167]; National Institute of Mental Health [P50113840].

Footnotes

The RCADS measure was identified in both our search for measures of anxiety and measures of depression. As such, it is counted separately for each category in our review, despite being the same measure.

References

- Adamson SJ, & Sellman JD (2003). A prototype screening instrument for cannabis use disorder: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test (CUDIT) in an alcohol-dependent clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Review, 22(3), 309–315. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, & Sellman JD (2010). An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 110(1–2), 137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annaheim B, Rehm J, & Gmel G (2008). How to screen for problematic cannabis use in population surveys: An evaluation of the Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test (CUDIT) in a Swiss sample of adolescents and young adults. European Addiction Research, 14(4), 190–197. doi: 10.1159/000141643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Athay MM, Riemer M, & Bickman L (2012). The Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS): Psychometric evaluation and discrepancies among youth, caregiver, and clinician ratings over time. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(1–2), 13–29. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0403-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashford J, Flett R, & Copeland J (2010). The Cannabis Use Problems Identification Test (CUPIT): Development, reliability, concurrent and predictive validity among adolescents and adults. Addiction, 105(4), 615–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02859.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, & Weisz JR (2015). Comprehensive treatments for youth comorbidity–evidence‐guided approaches to a complicated problem. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(3), 131–141. doi: 10.1111/camh.12092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Haimes EM, Jensen-Doss A, Birmaher B, Kendall PC, & Ginsburg GS (2018). Parent–youth informant disagreement: Implications for youth anxiety treatment. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry, 23(1), 42–56. doi: 10.1177/1359104516689586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Stewart RE, Walsh L, Lucas S, Downey MM, Jackson K, … Mandell DS (2015). Free, brief, and validated: Standardized instruments for low-resource mental health settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beusenberg M, Orley JH, & World Health Organization. (1994). A User’s guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ (No. WHO/MNH/PSF/94.8. Unpublished). Geneva: World Health Organization; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/61113 [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Douglas SR, De Andrade ARV, Tomlinson M, Gleacher A, Olin S, & Hoagwood K (2016). Implementing a measurement feedback system: A tale of two sites. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 410–425. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0647-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Kelley SD, Breda C, de Andrade AR, & Riemer M (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.002052011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birelson P (1981). The validity of depressive disorder in childhood and development of a self-rating scale: A research report. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22, 73–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, & Baugher M (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, & Altman D (1986). Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The Lancet, 327(8476), 307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn K, Doll HA, Cooper Z, O’Connor M, Palmer RL, & Fairburn CG (2008). The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(10), 1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Kraus DR, Miller SD, & Lambert MJ (2015). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: Benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychotherapy Research, 25(1), 6–19. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.817696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SJ, Krulewicz SP, & Kutcher S (2003). The Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale: Assessment of its evaluative properties over the course of an 8-week pediatric pharmacotherapy trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 13(3), 337–349. doi: 10.1089/104454603322572679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL, & Rounds LA (1995). Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: Criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 94(3), 135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, Dowling F, & Francis A (1996). Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 93(2), 129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Moffitt CE, & Gray J (2005). Psychometric properties of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(3), 309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Tracey SA, Brown TA, Collica TJ, & Barlow DH (1997). Assessment of worry in children and adolescents: An adaptation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(6), 569–581. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00116-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, & Weisz JR (2003). Applying treatment outcome research in clinical practice: Techniques for adapting interventions to the real world. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8(1), 3–10. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, & Fairburn CG (1987). The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(4), 485–494. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couwenbergh C, Van Der Gaag RJ, Koeter M, De Ruiter C, & Van den Brink W (2009). Screening for substance abuse among adolescents: Validity of the CAGE-AID in youth mental health care. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(6), 823–834. doi: 10.1080/10826080802484264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, … Wood C (2002). Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(4), 397–403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Stockings E, Patton G, Hall WD, & Lynskey M (2016). The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), 251–264. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE, & Rabinowitz J (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858. doi: 10.1037/a0038498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes & Langer DA (2018). Assessment and the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology’s evidence base updates series: Evaluating the tools for gathering evidence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(3), 357–365. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1458314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Gross HE, Gipson DS, Selewski DT, DeWitt EM, Dampier CD, … Varni JW (2015). PROMIS® pediatric self-report scales distinguish subgroups of children within and across six common pediatric chronic health conditions. Quality of Life Research, 24(9), 2195–2208. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0953-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SL, Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, & Spence SH (2010). The assessment of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: The revised Preschool Anxiety Scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 400–409. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen SV, Dickey B, & Sederer LI (2000). A self-report symptom and problem rating scale to increase inpatients’ involvement in treatment. Psychiatric Services, 51(3), 349–353. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.3.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sasagawa S, & Frick PJ (2006). Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment, 13(4), 454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE Jr., Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, … Burrows-MacLean L (2006). A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer CA, & Aman MG (2009). Development of the children’s scale of hostility and aggression: Reactive/proactive (C-SHARP). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1155–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulstich ME, Carey MP, Ruggiero L, Enyart P, & Gresham F (1986). Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: An evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC). American Journal of Psychiatry, 143(8), 1024–1027. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Asnaani A, Zang Y, Capaldi S, & Yeh R (2018). Psychometrics of the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 38–46. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1350962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, & Garfinkel PE (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12(4), 871–878. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700049163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Roberto CA, Seamans MJ, Corbin WR, & Brownell KD (2013). Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale for children. Eating Behaviors, 14(4), 508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Dickstein S, & Zeanah CH (2006). Further validation of the Early Childhood Screening Assessment. Presented at the 53rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry National Meeting, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, & Goodman R (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(4), 400–403. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goolsby J, Rich BA, Hinnant B, Habayeb S, Berghorst L, De Los Reyes A, & Alvord MK (2018). Parent–child informant discrepancy is associated with poorer treatment outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1228–1241. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0946-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Darke S, Griffiths P, Hando J, Powis B, Hall W, & Strang J (1995). The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): Psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction, 90(5), 607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2010). Improving the K6 short scale to predict serious emotional disturbance in adolescents in the USA. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(S1), 23–35. doi: 10.1002/mpr.314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton MAX (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32(1), 50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield DR, & Ogles BM (2007). Why some clinicians use outcome measures and others do not. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(3), 283–291. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0110-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerstrom KO (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson M, & Freeman CPL (1987). A self-rating scale for bulimia: The ‘BITE’. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(1), 18–24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, & Crawford JR (2005). The 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS–21): Normative data and psychometric evaluation in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(22), 227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, Ballard E, Klima J, Rosenstein DL, … Joshi P (2012). Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170–1176. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, & Mash EJ (2008). Developing criteria for evidence-based assessment: An introduction to assessments that work In Hunsley J & Mash EJ (Eds.), A guide to assessments that work. (pp. 3–14). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, & Mash EJ (2018). A guide to assessments that work (2nd ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Behavioral Research. (2007). Texas Christian University Drug Screen II. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research; Retrieved from http://www.ibr.tcu.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies P, McGarrigle L, & Ungar M (2018). The CYRM-R: A Rasch-validated revision of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 16(1), 70–92. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2018.1548403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Robinson J, Feins A, Lamb S, & Fenton T (1988). Pediatric Symptom Checklist: Screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. The Journal of Pediatrics, 112(2), 201–209. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A (2011). Practice involves more than treatment: How can evidence‐based assessment catch up to evidence‐based treatment? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(2), 173–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01248.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A (2015). Practical, evidence-based clinical decision making: Introduction to the special series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, & Hawley KM (2010). Understanding barriers to evidence-based assessment: Clinician attitudes toward standardized assessment tools. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(6), 885–896. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.517169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, & Weisz JR (2008). Diagnostic agreement predicts treatment process and outcomes in youth mental health clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 711–722. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Ehrenreich-May J, Nanda MM, Maxwell CA, LoCurto J, Shaw AM, … Ginsburg GS (2018). Community Study of Outcome Monitoring for Emotional Disorders in Teens (COMET): A comparative effectiveness trial of a transdiagnostic treatment and a measurement feedback system. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 74, 18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Becker-Haimes EM, Smith AM, Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Stanick CF, & Hawley KM (2018). Monitoring treatment progress and providing feedback is viewed favorably but rarely used in practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(1), 48–61. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0763-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Smith AM, Becker-Haimes EM, Ringle VM, Walsh LM, Nanda M, … & Lyon AR (2018). Individualized progress measures are more acceptable to clinicians than standardized measures: Results of a national survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 392–403. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0833-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2002). The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(3), 196–204. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00333-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr., Pfaff JJ, & Acres JG (2002). A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: Reliability and validity data from the Australian National General Practice Youth Suicide Prevention Project. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(4), 471–481. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00017-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao UMA, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rodgers A, & Colbus D (1986). The Hopelessness Scale for Children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 241–245. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SM, Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG, Kirk A, O’Grady KE, & Schwartz RP (2014). Validity of brief screening instrument for adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. Pediatrics, 133(5), 819–826. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenardy JA, Spence SH, & Macleod AC (2006). Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in children after accidental injury. Pediatrics, 118(3), 1002–1009. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten P, Czuba K, McPherson K, Dudley M, Elder H, Tauroa R, & Vandal A (2016). A systematic review of evidence for the psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(1), 64–75. doi: 10.1177%2F0165025415570647 [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL (2006). The subjective well-being of America’s youth: Toward a comprehensive assessment. Adolescent & Family Health, 4(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth-Rublee B, Ramanuj P, O’Brien RW, Tomoyasu N, & Pincus HA (2018). Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: A global perspective. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 30–38. doi: 10.1002/wps.20482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JB, Lavigne JV, & Seshadri R (2010). Clinician‐assigned and parent‐report questionnaire‐derived child psychiatric diagnoses: Correlates and consequences of disagreement. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(3), 375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Becan JE, Landrum B, Joe GW, & Flynn PM (2014). Screening and assessment tools for measuring adolescent client needs and functioning in substance abuse treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(7), 902–918. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.891617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, & Shaffer HJ (1999). A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153(6), 591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotte A, Hill KA, Mah AC, Korathu-Larson PA, Au JR, Izmirian S, … Higa-McMillan CK (2016). Facilitators and barriers of implementing a measurement feedback system in public youth mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 861–878. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0729-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberger WG, Giauque AL, & Dunn DW (2007). Development and validation of the outburst monitoring scale for children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17(4), 511–526. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz S, Van Dyck Z, Dremmel D, Munsch S, & Hilbert A (2015). Early-onset restrictive eating disturbances in primary school boys and girls. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(7), 779–785. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0622-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M (2007). Presidential address: What we have learned from a decade of research aimed at improving psychotherapy outcome in routine care. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10503300601032506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Hawkins EJ, Vermeersch DA, Nielsen SL, & Smart DW (2003). Is it time for clinicians to routinely track patient outcome? A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 288–301. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Joiner TE Jr., Rudolph KD, Potter KI, Lambert S, … Gathright T (1999). A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 326. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Weiss R, Sherritt L, Ziemnik R, Spalding A, Van Hook S, & Shrier LA (2014). An electronic screen for triaging adolescent substance use by risk levels. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(9), 822–828. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Perrine N, Dierker L, & Kelley ML (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1183–1192. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700027X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, Bearden CE, & Cannon TD (2011). Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire—brief version (PQ-B). Schizophrenia Research, 129(1), 42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loflin M, Babson K, Browne K, & Bonn-Miller M (2018). Assessment of the validity of the CUDIT-R in a subpopulation of cannabis users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(1), 19–23. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1376677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney JP, & Milich R (1982). Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical practice In Wolraich M & Routh DK (Eds.), Advances in developmental and behavioral pediatrics (2nd ed.) (113–147). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught AL, Brown K, & Spitznagel E (2004). The preschool feelings checklist: A brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 708–717. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Abbott MJ, & Rapee RM (2007). Interrater reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent version. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(6), 731–736. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180465a09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Sburlati ES, Abbott MJ, Rapee RM, Hudson JL, Tolin DF, & Carlson SE (2013). Psychometric properties of the Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale (CALIS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(7), 711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Street AK, Abbott MJ, & Rapee RM (2008). Psychometric properties of the school anxiety scale—Teacher report (SAS-TR). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(2), 292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, Dorsey S, Pullmann M, Silbaugh-Cowdin J, & Berliner L (2015). Clinician use of standardized assessments following a common elements psychotherapy training and consultation program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(1), 47–60. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0543-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, Hendrix E, & Liu F (2016). Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: Results from a comprehensive review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 441–466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, Pullmann MD, Whitaker K, Ludwig K, Wasse JK, & McCauley E (2019). A digital feedback system to support implementation of measurement-based care by school-based mental health clinicians. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(sup1), S168–S179. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1280808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney MJ, McGuire JB, & Daniels SR (1988). Reliability testing of a children’s version of the Eating Attitude Test. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 541–543. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamah D, Owoso A, Sheffield JM, & Bayer C (2014). The WERCAP screen and the WERC stress screen: Psychometrics of self-rated instruments for assessing bipolar and psychotic disorder risk and perceived stress burden. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(7), 1757–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Copeland J, Gilmour S, Gates P, & Swift W (2006). The adolescent cannabis problems questionnaire (CPQ-A): Psychometric properties. Addictive Behaviors, 31(12), 2238–2248. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Copeland J, Gates P, & Gilmour S (2006). The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) in an adolescent population of cannabis users: Reliability, validity and diagnostic cut-off. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83(1), 90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash EJ, & Barkley RA (Eds.). (2007). Assessment of childhood disorders (4th ed.). New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, Srinivasan J, McCann S, Konarski JZ, & Kennedy SH (2004). The antidepressant effects of risperidone and olanzapine in bipolar disorder. Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 11(2), e218–e226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay D (2019). Introduction to the Special Issue: Mechanisms of Action in Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. Behavior Therapy. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, & Ollendick TH (Eds.). (2013). Diagnostic and behavioral assessment in children and adolescents: A clinical guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P, Bryant R, Salmon K, Yule W, Dalgleish T, & Nixon RD (2009). Development and validation of the Child Post‐Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (CPTCI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 432–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer SC, Angold A, Costello EJ, & Loeber R, Van Kammen W, & Stouthamer-Loeber M (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents: Factor composition and structure across development. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ng MY, & Weisz JR (2016). Annual research review: Building a science of personalized intervention for youth mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 216–236. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogles BM, Melendez G, Davis DC, & Lunnen KM (2001). The Ohio scales: Practical outcome assessment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(2), 199–212. doi: 10.1023/A:1016651508801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]