Abstract

Purpose:

Head impact exposure (HIE) (i.e., magnitude and frequency of impacts) can vary considerably among individuals within a single football team. To better understand individual-specific factors that may explain variation in head impact biomechanics, this study aimed to evaluate the relationship between physical performance measures and HIE metrics in youth football players.

Methods:

Head impact data were collected from youth football players using the Head Impact Telemetry (HIT) System. HIE was quantified in terms of impact frequency, linear and rotational head acceleration, and risk-weighted cumulative exposure metrics (RWELinear, RWERotational, and RWECP). Study participants completed 4 physical performance tests: vertical jump, shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint. The relationships between performance measures and HIE metrics were evaluated using linear regression analyses.

Results:

A total of 51 youth football athletes (ages: 9–13 years old) completed performance testing and received a combined 13,770 head impacts measured with the HIT System for a full season. All performance measures were significantly correlated with total number of impacts in a season, RWELinear–Season, and all RWE-Game metrics. The strongest relationships were between 40 yard sprint speed and all RWE-Game metrics (all p≤0.0001 and partial R2>0.3). The only significant relationships among HIE metrics in practice were between shuttle run speed and total practice impacts and RWELinear–Practices, 40 yard sprint speed and total number of practice impacts, and 3-cone speed and 95th percentile number of impacts/practice.

Conclusion:

Generally, higher vertical jump height and faster times in speed and agility drills were associated with higher HIE, especially in games. Physical performance explained less variation in HIE in practices, where drills and other factors, such as coaching style, may have a larger influence on HIE.

Keywords: Biomechanics, Head Acceleration, Strength, Speed, Football

Introduction

There is a growing body of research suggesting a relationship between repetitive head impacts in sports, even in the absence of a clinically diagnosed concussion, with measurable changes in brain imaging and neurocognitive ability after a single season of participation (1–3). There is also concern for long-term neurocognitive deficits that may result from accumulating numerous concussive and non-concussive head impacts over many years of playing football and other contact sports (4–7). Head impact exposure (HIE), or the frequency and magnitude of on-field head impacts, has been studied using head acceleration measurement devices in football athletes to better understand the biomechanics of concussive and subconcussive impacts at all levels of play (8–11). However, the effect of confounding factors such as age of first exposure to head impacts, number of concussions, as well as the number and severity of subconcussive head impacts accumulated over a lifetime is not well understood (12, 13).

Although a growing body of literature has shown that both the severity and number of head impacts increases with level of play in football, there is significant variability in HIE among individual athletes, even at the same level of play (9, 10, 14, 15). For instance, on a single high school football team the 95th percentile linear acceleration and total number of impacts per season can vary from 39 g to 73 g and from 129 to 1258, respectively (11). Youth football players also have considerable variability in HIE on a single team with 95th percentile linear acceleration and total number of impacts ranging from 25 g to 54 g (14) and 26 to 1,003 (10), respectively. Differences in position may account for some of the variation at the high school and college level, but less so at the youth level where athletes often play a number of positions (9, 16, 17). Other variables such as player behavior and tackling technique may also affect individual HIE (18–20). A study of youth ice hockey players evaluated the effect of athlete aggression on HIE using the Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (CAAS) and found that less aggressive adolescent boys sustained head impacts of less rotational acceleration compared to more aggressive adolescent boys in practices (18). Additionally, greater tackling technique proficiency has been associated with lower numbers of high severity head impacts in youth football players (21).

Significant variability in body size, physical ability, and strength among the youth population may also contribute to differences in HIE among athletes (22–24). Physical performance characteristics have been suggested as risk factors for concussion and other injuries in football, with faster and stronger athletes potentially more likely to engage in contact (22, 25, 26). Additionally, strength and fitness training has been used to improve physical ability and reduce injury (primarily musculoskeletal), but excessive training can also result in increased likelihood of injury either from overuse and fatigue or from pushing an athlete to higher intensity (27, 28). While the effect of physical ability and fitness on head impacts in football is not well understood, it was hypothesized that physical performance may play a role in an athlete’s HIE (22, 23). Understanding how physical ability and HIE relate to one another may aid in identifying athletes at risk for experiencing higher HIE as well as developing and implementing individual or team-level interventions aimed to reduce HIE. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between physical performance measures and HIE in youth football players.

Methods

Physical performance measures, demographic, and head impact data were collected from youth football athletes participating on four youth football teams (A, B, C, and D). The athletes were placed on teams based on the national governing organization’s age and weight requirements (Table 1). This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and written participant assent and parental consent were properly acquired for participation in the study. All athletes also had to properly fit into a Riddell Speed or Revolution Youth medium size or larger helmet to be included in the study. Participation in the study was voluntary.

Table 1.

Age and weight requirements for each team. Teams A and C were age and weight restricted and teams B and D were only age restricted. For example, athletes on team A that are 12 years old or younger cannot weigh more than 165 lb. and 13 year old athletes cannot weigh more than 145 lb. (i.e. they are older/lighter athletes); whereas athletes on team B, a weight unlimited team, cannot be older than 12 years old, but they do not have any weight restrictions.

| Teams | Age Requirements (years) | Max Weight with Equipment (lbs) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 12 and under 13 |

165 145 |

| B | 12 and under | Unlimited |

| C | 10 and under 11 |

129 109 |

| D | 10 and under | Unlimited |

Physical Performance Data Collection

Study participants completed 4 physical performance tests commonly used to evaluate speed, power, and agility during a youth combine event organized by the research team (22, 29). The performance tests included the vertical jump, shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint. These tests were chosen because they are commonly used to assess physical ability, facilitating comparison with prior studies (22, 25, 30). Additionally, the tests could be completed on-field for data collection in a large group setting. Performance testing of each athlete was completed in a single session after the first week of no-contact conditioning practices. Contact practices started the following week. Height was measured by a study member during the combine event. Weight was measured at a separate pre-season testing appointment that occurred within 7 weeks of the combine event. Prior to completing the physical performance testing, athletes warmed up with their team, under the instruction of their coach, for up to 25 minutes. Next, the athletes completed the performance testing by rotating through stations with their team. The teams were randomly assigned to an initial physical performance testing station. Trained research assistants were at each station to provide instruction, run the tests, and record the data.

Each athlete completed 3 trials of the vertical jump and 2 trials each of the speed and agility drills (shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint). To measure vertical jump height, the athlete coated the fingertips on their dominant hand with chalk and the maximal height reached by the athlete’s hand while their feet remained flat on the ground was recorded as their standing height. Then, the athlete completed 3 vertical jumps, jumping as high as they could while marking the wall with their dominant hand and the height of each jump was measured. Athletes were allowed up to 1 minute between jumps to recover before making another attempt. Chalk was re-applied to their fingertips between each jump or as needed. The highest jump height was used for analysis.

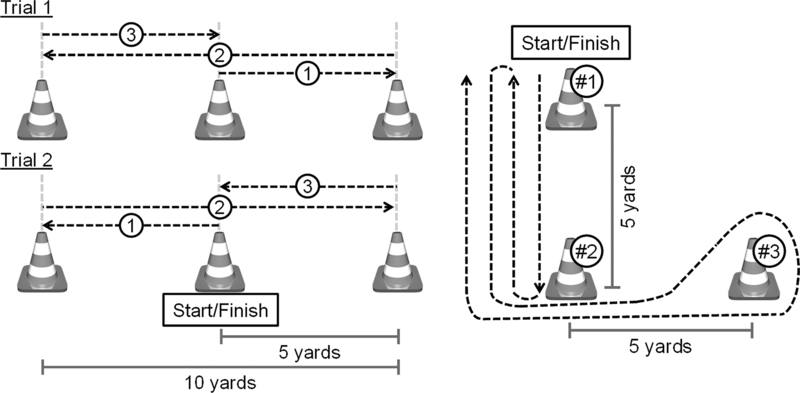

For the shuttle run test, the athletes aligned themselves with a center cone and were instructed to complete the test as fast as they could. When instructed to start, the athletes sprinted 5 yards to the right, then 10 yards to the left, and finished by sprinting 5 yards through the center cone. For the second trial, the direction was reversed and the athletes began by sprinting 5 yards to the left (Figure 1). For the 3-cone drill, three cones were placed in an L-shape. The athletes were instructed to begin at cone #1, sprint to cone #2, sprint back to cone #1, then sprint to the outside of cone #2 towards the inside of cone #3, wrap around cone #3, sprint back to the outside of cone #2, and finish through cone #1 as fast as they could (Figure 1). For the 40 yard sprint, cones were set-up from the 40 yard line to the goal line to mark a straight lane and athletes were instructed to sprint along this line as fast as they could. If an athlete made a mistake during any performance test (e.g. trips, misses a turn, knocks over a cone, etc.) they were given one opportunity to re-do the trial. The fastest shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint speeds were used for analysis.

Figure 1.

Setup for the (left) shuttle run and (right) 3-cone drills.

Head Impact Data Collection

Head impact data were collected for all pre-season, regular season, and playoff practices and games by instrumenting Riddell helmets worn by study participants with Head Impact Telemetry (HIT) System MxEncoders that mount within the existing padding of the helmet. The MxEncoders include an array of six single-axis accelerometers, a telemetry unit, data storage device, and battery pack. The accelerometers are spring-mounted to allow the encoder to remain in contact with the head throughout the duration of a head impact, ensuring measurement of head acceleration, not helmet acceleration (31). The HIT System also includes a sideline data collection base unit, which is connected to a radio receiver to collect head impacts in real-time. Trained research assistants monitored the HIT System at all practices and games. The data processing algorithm, validation of the HIT System, and data collection methodology used in this study have been previously described in the literature (10, 32). Video was also recorded for all sessions and time-synched with the HIT System to verify the times that the athletes were helmeted. Impacts occurring while the players were not wearing helmets (i.e. a dropped helmet) were removed from the data set.

Statistical Analysis

HIE was quantified in terms of number of impacts, peak head acceleration, and risk-weighted cumulative exposure (RWE) metrics. Total number of impacts in the season and number of impacts per session were computed for each player. The 95th percentile impacts per session for each player were used for statistical analysis. Head acceleration was described in terms of 95th percentile linear and rotational acceleration. The RWE metric is a cumulative exposure metric that combines the magnitude and frequency of hits experienced by an athlete on aggregate (11, 33). To compute RWE, the risk of concussion for each player’s head impact is computed and summed to generate the RWE for the season. Logistic regression is used to define three risk functions: 1) linear acceleration (RWELinear) (34), 2) rotational acceleration (RWERotational) (35), and 3) the combined probability from linear and rotational acceleration (RWECP) (33). HIE was evaluated overall and separately by session type, practice or competition. One-way ANOVA was used to compare performance measures among teams. Linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the relationships between physical performance measures and HIE metrics. The linear models were adjusted for team and primary playing position (A – line [i.e. offensive & defensive line], B – back or perimeter [e.g. wide receiver], and C – multiple positions). Partial R2 were used to describe strength of associations after accounting for systematic differences among teams and positions. For each linear regression, Cook’s distance was computed and outliers were removed accordingly. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

A total of 51 youth football athletes participated in the physical performance testing and were instrumented with the HIT System for a full season. The age, height, and weight data for the athletes are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 52.9% of the subjects were considered to be a normal and healthy weight, 25.5% were overweight, and 21.6% were obese (36, 37).

Table 2.

Summary of demographics data (mean ± standard deviation) for all athletes and stratified by team.

| Team A | Team B* | Team C | Team D* | All Teams | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 15 | 14 | 9 | 13 | 51 |

| Age (yrs) | 13.4 ± 0.4 | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 11.6 ± 0.3 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 12.0 ± 1.2 |

| Height (cm) | 166.9 ± 7.4 | 160.5 ± 6.1 | 149.1 ± 4.6 | 148.1 ± 6.9 | 157.2 ± 10.2 |

| Mass (kg) | 61.3 ± 8.5 | 63.9 ± 17.5 | 44.0 ± 5.6 | 43.0 ± 9.7 | 54.3 ± 14.8 |

| BMI | 22.1 ± 3.3 | 24.7 ± 6.2 | 19.7 ± 2.0 | 19.5 ± 3.8 | 21.7 ± 4.6 |

Team did not have weight restrictions

Physical Performance

Results from the physical performance tests are summarized in Table 3. There was significant variation in all physical performance measures among teams. Team A had the highest mean vertical jump height and fastest mean shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint speed compared to the other teams. The weight unlimited teams, B and D, had the lowest mean vertical jump height and slowest mean speed in the speed and agility drills.

Table 3.

Summary of performance testing results (mean ± standard deviation) for all athletes and stratified by team.

| Team A | Team B | Team C | Team D | All Teams | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Jump (cm) | 47.6 ± 10.3 | 34.9 ± 6.9 | 37.6 ± 5.7 | 34.7 ± 5.5 | 39.1 ± 9.3 |

| Shuttle Run (s) | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.6 |

| 3-cone (s) | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 10.0 ± 1.0 | 9.3 ± 1.0 |

| 40 Yard Sprint (s) | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 0.7 |

Head Impact Exposure

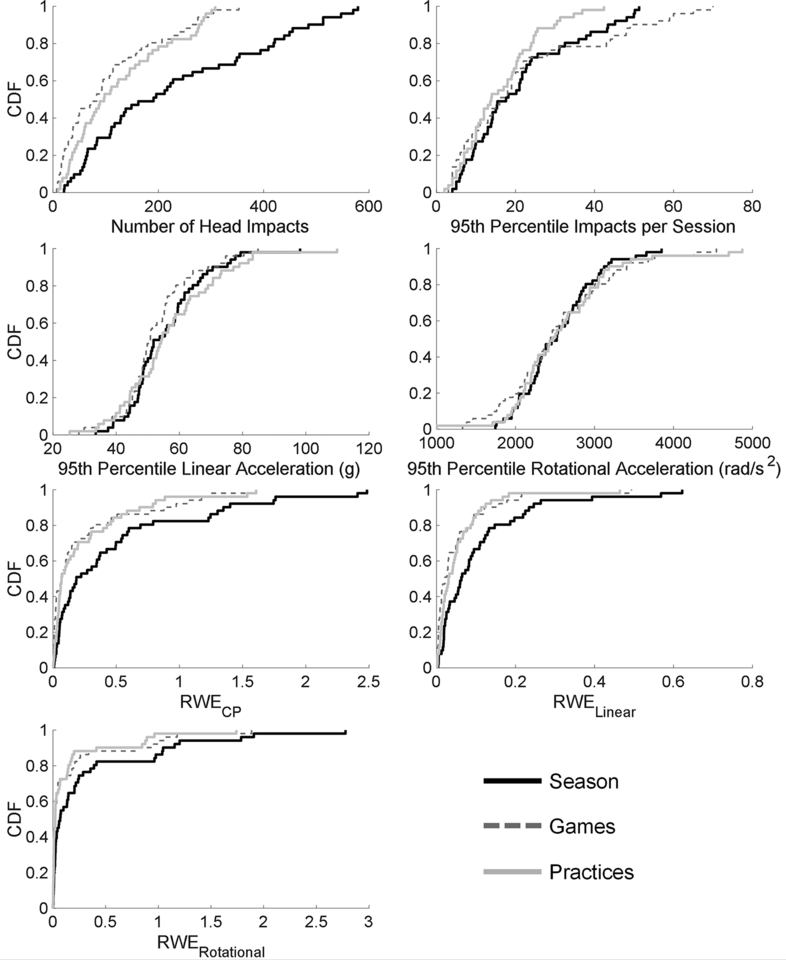

A total of 13,770 head impacts were collected among all athletes. Empirical cumulative distribution plots summarizing HIE metrics for all athletes are shown in Figure 2. The median [95th percentile] linear and rotational accelerations of all impacts were 19.3 [54.4] g and 945.6 [2,545.6] rad/s2, respectively. The distribution of the total number of head impacts in a season for each athlete ranged from 21 to 579 impacts with a median of 191 impacts. Teams participated in an average of 13 ± 2 games and 36 ± 3 practices during the season.

Figure 2.

Empirical cumulative distribution (CDF) plots of HIE metrics stratified by session type.

Relationship Between Physical Performance and HIE

The physical performance measures were significantly correlated with several HIE metrics with adjustment for the covariates of team and position (Table 4). All performance measures were significantly correlated with total number of impacts in a season and RWELinear – Season. Faster 40 yard sprint times were significantly associated with higher RWECP – Season (p = 0.01), RWELinear – Season (p = 0.003), and RWERotational – Season (p = 0.02). For all statistically significant relationships, higher vertical jump height and faster times for the speed and agility drills were associated with higher HIE, with the exception of the relationships between season 95th percentile linear acceleration and shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint speed. For these three significant correlations, greater 95th percentile linear acceleration was inversely correlated with slower times for the speed and agility drills. On the other hand, when evaluating head impacts just experienced during games, faster times for the speed and agility drills tended to be associated with greater 95th percentile linear acceleration in games, although the relationships were not significant.

Table 4.

Summary of linear regression analyses results (outcome = HIE metric, predictor = physical performance measure) controlling for team and position. For each linear regression, the Cook’s distance was computed and outliers were removed. Bolded and italicized results are significant at p < 0.05.

| Vertical Jump | Shuttle Run | 3-cone | 40 Yard Sprint | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial R2 |

Type III p-value |

Partial R2 |

Type III p-value |

Partial R2 |

Type III p-value |

Partial R2 |

Type III p-value |

||

| Season | Total Number of Impacts | 0.19 | 0.004 | 0.20 | 0.002 | 0.22 | 0.002 | 0.20 | 0.003 |

| 95th %ile Linear Acc. (g) | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.009 | |

| 95th %ile Rotational Acc. (rad/s2) | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.00 | 0.9 | |

| 95th %ile Impacts/Session | 0.25 | 0.0008 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.01 | |

| RWECP | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.008 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.01 | |

| RWELinear | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.003 | 0.23 | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.003 | |

| RWERotational | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.02 | |

| Games | Total Number of Impacts | 0.22 | 0.001 | 0.21 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.002 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| 95th %ile Linear Acc. (g) | 0.00 | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.5 | |

| 95th %ile Rotational Acc. (rad/s2) | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.03 | |

| 95th %ile Impacts/Game | 0.26 | 0.0007 | 0.18 | 0.007 | 0.24 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| RWECP | 0.27 | 0.0004 | 0.23 | 0.0009 | 0.22 | 0.002 | 0.37 | 0.0001 | |

| RWELinear | 0.19 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.0006 | 0.24 | 0.0008 | 0.30 | 0.0001 | |

| RWERotational | 0.23 | 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.0003 | 0.22 | 0.002 | 0.37 | 0.0001 | |

| Practices | Total Number of Impacts | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| 95th %ile Linear Acc. (g) | 0.00 | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.3 | |

| 95th %ile Rotational Acc. (rad/s2) | 0.00 | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.00 | 1.0 | |

| 95th %ile Impacts/Practice | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.07 | |

| RWECP | 0.00 | 0.7 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.4 | |

| RWELinear | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.20 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.2 | |

| RWERotational | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

Physical performance measures were significantly correlated with most HIE metrics in games but explained less variation in HIE in practice. Higher vertical jump height and faster times in the shuttle run, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint were associated with significantly higher risk-weighted cumulative exposure in games (RWECP – Games, RWELinear – Games, RWERotational – Games). The strongest relationships were between 40 yard sprint speed and all RWE – Game metrics (all p ≤ 0.0001 and partial R2 > 0.3). Better performances in the vertical jump, shuttle run, and 3-cone were also significantly correlated with higher total number of impacts in games. Additionally, better performances in the vertical jump, 3-cone, and 40 yard sprint were significantly correlated with a higher 95th percentile number of impacts per game. However, the only significant relationships between physical performance and HIE metrics in practices were between shuttle run speed and total number of practice impacts and RWELinear – Practices, 40 yard sprint speed and total number of practice impacts, and 3-cone speed and 95th percentile number of impacts per practice. Vertical jump height was not significantly associated with any HIE metrics in practices. It should be noted that the overall linear models of HIE metrics in practices, with the exception of the 95th percentile rotational acceleration in practices, were significant (all p < 0.01).

Discussion

The significant variability in HIE observed among football athletes, even on the same team, prompted this investigation into the relationship between physical performance measures and HIE metrics in youth football players (9, 10, 14). Our results suggest that higher vertical jump height and faster speed and agility drill performance were associated with higher head impact severity, impact frequency, and total number of impacts. However, physical performance explained more variation in HIE in games compared to practices.

The HIE metrics most strongly associated with all physical performance measures were RWE metrics, which scales each impact’s contribution to the athlete’s cumulative exposure according to the nonlinear relationship between acceleration and risk of concussion (11). The strong relationship between physical performance measures and RWE metrics suggests that physical performance is related to both the number and severity of impacts, especially in games. Of the three RWE metrics, the physical performance metrics most frequently correlated with RWELinear followed by RWECP; however, all performance metrics were still significantly associated with RWERotational-Games and 40 yard sprint speed was associated with RWERotational-Season. Given the strong relationships among all three RWE metrics and that most real-world impacts involve both linear and rotational components; future studies may only need to evaluate RWECP. Overall, these results suggest that youth athletes with greater ability in these types of physical performance tests may experience higher HIE. This may be due to these athletes engaging in a higher number of contact scenarios resulting in greater head impact severity. Scenarios associated with higher head impact magnitudes may involve tackling at a higher speed and/or from a larger closing distance (38, 39). Athletes with greater physical performance may also prioritize speed and strength over technical skill when engaging in contact; however, more in-depth analyses of on-field behaviors, tackling technique, and playing style of youth football players are needed to better understand how speed and strength of athletes relates to HIE.

Physical performance measures were more frequently and more strongly associated with HIE metrics in games compared with practices. Although the teams included in this study abided by mandatory play rules, which required each athlete to participate in a minimum number of plays depending on how many athletes are present, it is likely that more physically fit, faster, and stronger athletes are given more playing time and may be more likely to engage in contact during plays while on the field. The amount of playing time in games was not quantified for each athlete in this study, but it may be beneficial to consider playing time in future work. It should be noted, though, that the quality of contact (i.e. tackling technique) among athletes should also be considered. Although the effect of tackling technique on head impact biomechanics in youth football is not well-understood, a recent laboratory study of youth football players found that training in a vertical, head up tackling style and decreasing step length decreased head impact severity (21). This is further supported by on-field evaluations of tackle technique in rugby, which have shown that characteristics such as “head up and forward/face up” and “shortening steps” were identified as having a lower propensity to result in a head injury assessment (40). Additionally, the amount of time spent on and importance of tackle training and technique to prevent injury was associated with behaviors that reduce the risk of injury in games in junior rugby players, suggesting that spending time on teaching tackling technique in practice may be effective in reducing HIE in games (41). Athletes, especially those identified as having high physical performance measures, may benefit from additional training to improve tackling technique that emphasizes characteristics such as keeping their head up and shortening steps prior to contact.

The greater number and strength of relationships between physical performance and HIE metrics in games compared to practices may also be due to the influence individual teams and their coaches have on HIE in practices. Prior investigations into HIE in practice drills have demonstrated significant variability in HIE among drills and that activities during practice significantly affect HIE (38, 39, 42). For example, a 5-minute decrease in tackling or blocking drills could result in a 19% reduction in the number of practice impacts greater than 40g (39). Additionally, efforts to reduce HIE, such as limiting the amount of time allowed for contact in practice and eliminating certain drills, demonstrate the influence coaches and practice structure have on the number of head impacts athletes experience in practice. For instance, a youth football team that implemented Pop Warner’s 2012 rule change to limit contact in practice had 37–46% fewer impacts than athletes on teams that did not have restrictions to contact in practice, but head impact severity was not significantly reduced (14). Efforts to moderate HIE in practice should continue to focus on modifying drills and practice structure.

All physical performance measures were significantly associated with several HIE metrics, but the 40 yard sprint had the strongest relationship with RWE metrics during games. The strong relationship between sprint speed and RWE in games may be due to faster athletes being involved in more tackles and contact events because they can run quickly to join the ‘play’. Faster athletes may also be more likely to be involved in full-speed tackling scenarios, which have been shown to be associated with higher impact magnitude (38, 39). However, other factors may play a role as well, such as player aggression, competitiveness, and attitudes and behaviors towards tackling. For example, youth ice hockey players that were categorized as higher aggression, from the results of a questionnaire, experienced significantly greater rotational head acceleration during practices (18). The confluence of physical performance and intrinsic characteristics, such as aggression, warrant further study to better understand the individual variability in HIE and develop targeted intervention strategies to reduce HIE.

Although not directly related to head trauma, numerous studies have shown that physical fitness training can improve performance and reduce injury at all levels of play and across a wide range of sports (27, 28). Improved strength and speed are associated with better tolerance to higher workloads and reduced odds of injury (27). Improving physical fitness is also important, especially in the youth population, given that childhood obesity has become a major public health concern (37); however, there is also evidence that greater physical fitness training loads are related to higher injury rates potentially due to excessive and rapid increases in training resulting in overuse and fatigue-related injuries (28). Athletic trainers, sports medicine practitioners, and coaches should be aware that higher performing athletes may be more likely to experience greater HIE. In addition to individual-level interventions, such as improving tackling technique, team-level interventions, such as rule changes, may also aid in reducing HIE in games. For example, moving the kickoff line from the 35 yard to the 40 yard line and moving the touchback line from the 25 yard to the 20 yard line significantly reduced the concussion rate in collegiate football players (43). Additionally, restructuring mandatory play rules so playing time is more evenly distributed among youth football players may mitigate HIE in higher performing athletes, but may also increase HIE in other individuals, which must be considered. Further research is needed to develop effective intervention strategies that optimize technical skill and physical fitness while reducing HIE, especially in high performing athletes.

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted. First, it provides a limited representation of youth football athletes as a whole, as all study participants were from the same region and functioned under the same national youth football organization. While HIE metrics, physical performance measures, and anthropometric measures in this cohort of youth football athletes who ranged in age from 9–13 years old were comparable to previously published studies, future work should include teams from a variety of other organizations, regions, and demographic/cultural backgrounds (10, 14, 22, 23). The speed and agility drills were timed using handheld stopwatches and there is variability using this device; however, given the nature of the large data collection effort at this youth football combine event, handheld stopwatches were logistically most feasible. The physical performance testing included 4 measures, but was not a comprehensive assessment of all physical performance metrics and did not include measures such as upper body strength and VO2 max. Further research will include a more comprehensive testing protocol with a wider variety of measures that may be more sensitive to predicting HIE. The randomized simultaneous start design for the performance testing meant that not all athletes completed the testing in the same order, which could have potentially influenced the results. However, prior studies have also used a randomized simultaneous start design to evaluate physical performance in athletes (22, 30). Additionally, athletes were given adequate time between performance drills to recover and take water breaks as needed throughout the testing. The concussion risk curve used in the RWE metrics was derived from a collegiate population and may not directly translate to concussion risk in youth football athletes; however, the RWE metrics non-linearly weight the magnitude of each impact and incorporates both the number and severity of impacts an athlete experiences on aggregate. Lastly, the HIT System used for biomechanical data collection has some error associated with individual impact acceleration measurements and impact detection. However, the error of acceleration measurements is within the range of acceptable error for other measurement devices (8).

Conclusions

Overall, greater physical performance measures were significantly associated with higher HIE metrics. Physical performance measures also explained more variation in HIE in games than in practices. The strongest relationships were between 40 yard sprint speed and all three RWE metrics in games. Physical performance may aid in identifying athletes at greater risk of experiencing higher HIE and should be considered as part of intervention strategies for reducing HIE; however, further research is needed to better understand how HIE could be reduced in high performing athletes. Individual-level interventions targeted toward high performing athletes may emphasize skill development such as engaging in proper tackling technique and reducing speed prior to contact. Greater understanding of the factors that influence an individual’s HIE is important to develop additional evidence-based strategies to reduce HIE.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01NS094410 and R01NS082453. The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR001421 supported Dr. Jillian E. Urban. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors give special thanks to the Childress Institute for Pediatric Trauma at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center for providing support for this study. The authors also thank the youth football league’s coordinators, coaches, parents, athletes, and athletic trainer whose support made this study possible. The authors also thank all the research assistants that helped with physical performance and head impact data collection.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

References

- 1.Davenport EM, Apkarian K, Whitlow CT, Urban JE, Jensen JH, Szuch E, et al. Abnormalities in Diffusional Kurtosis Metrics Related to Head Impact Exposure in a Season of High School Varsity Football. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(23):2133–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahrami N, Sharma D, Rosenthal S, Davenport EM, Urban JE, Wagner B, et al. Subconcussive Head Impact Exposure and White Matter Tract Changes over a Single Season of Youth Football. Radiology. 2016;281(3):919–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talavage TM, Nauman EA, Breedlove EL, Yoruk U, Dye AE, Morigaki KE, et al. Functionally-detected cognitive impairment in high school football players without clinically-diagnosed concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(4):327–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavett BE, Stern RA, McKee AC. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(1):179–88, xi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(7):709–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montenigro PH, Bernick C, Cantu RC. Clinical features of repetitive traumatic brain injury and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Pathol. 2015;25(3):304–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailes JE, Petraglia AL, Omalu BI, Nauman E, Talavage T. Role of subconcussion in repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(5):1235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckwith JG, Greenwald RM, Chu JJ. Measuring head kinematics in football: correlation between the head impact telemetry system and Hybrid III headform. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(1):237–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broglio SP, Surma T, Ashton-Miller JA. High school and collegiate football athlete concussions: a biomechanical review. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley ME, Urban JE, Miller LE, Jones DA, Espeland MA, Davenport EM, et al. Head Impact Exposure in Youth Football: Comparing Age and Weight Based Levels of Play. J Neurotrauma. 2017; 34(11):1939–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban JE, Davenport EM, Golman AJ, Maldjian JA, Whitlow CT, Powers AK, et al. Head impact exposure in youth football: high school ages 14 to 18 years and cumulative impact analysis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(12):2474–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon GS, Kuhn AW, Zuckerman SL, Casson IR, Viano DC, Lovell MR, et al. Participation in Pre-High School Football and Neurological, Neuroradiological, and Neuropsychological Findings in Later Life: A Study of 45 Retired National Football League Players. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1106–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamm JM, Bourlas AP, Baugh CM, Fritts NG, Daneshvar DH, Martin BM, et al. Age of first exposure to football and later-life cognitive impairment in former NFL players. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cobb BR, Urban JE, Davenport EM, Rowson S, Duma SM, Maldjian JA, et al. Head impact exposure in youth football: elementary school ages 9–12 years and the effect of practice structure. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(12):2463–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong RH, Wong AK, Bailes JE. Frequency, magnitude, and distribution of head impacts in Pop Warner football: the cumulative burden. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;118:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crisco JJ, Wilcox BJ, Beckwith JG, Chu JJ, Duhaime AC, Rowson S, et al. Head impact exposure in collegiate football players. J Biomech. 2011;44(15):2673–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broglio SP, Williams RM, O’Connor KL, Goldstick J. Football Players’ Head-Impact Exposure After Limiting of Full-Contact Practices. J Athl Train. 2016;51(7):511–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt JD, Pierce AF, Guskiewicz KM, Register-Mihalik JK, Pamukoff DN, Mihalik JP. Safe-Play Knowledge, Aggression, and Head-Impact Biomechanics in Adolescent Ice Hockey Players. J Athl Train. 2016;51(5):366–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burger N, Lambert MI, Viljoen W, Brown JC, Readhead C, Hendricks S. Tackle technique and tackle-related injuries in high-level South African Rugby Union under-18 players: real-match video analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(15):932–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr ZY, Yeargin SW, Valovich McLeod TC, Mensch J, Hayden R, Dompier TP. Comprehensive Coach Education Reduces Head Impact Exposure in American Youth Football. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(10):2325967115610545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schussler E, Jagacinski RJ, White SE, Chaudhari AM, Buford JA, Onate JA. The Effect of Tackling Training on Head Accelerations in Youth American Football. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13(2):229–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caswell SV, Ausborn A, Diao G, Johnson DC, Johnson TS, Atkins R, et al. Anthropometrics, Physical Performance, and Injury Characteristics of Youth American Football. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(8):2325967116662251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malina RM, Morano PJ, Barron M, Miller SJ, Cumming SP. Growth status and estimated growth rate of youth football players: a community-based study. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(3):125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeargin SW, Kingsley P, Mensch JM, Mihalik JP, Monsma EV. Anthropometrics and maturity status: A preliminary study of youth football head impact biomechanics. Int J Psychophysiol. 2017;132(Pt A):87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupler TL, Amonette WE, Coleman AE, Hoffman JR, Wenzel T. Anthropometric and performance differences among high-school football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(8):1975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontos AP, Elbin RJ, Fazio-Sumrock VC, Burkhart S, Swindell H, Maroon J, et al. Incidence of sports-related concussion among youth football players aged 8–12 years. J Pediatr. 2013;163(3):717–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zouita S, Zouita AB, Kebsi W, Dupont G, Ben Abderrahman A, Ben Salah FZ, et al. Strength Training Reduces Injury Rate in Elite Young Soccer Players During One Season. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(5):1295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabbett TJ. The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(5):273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sierer SP, Battaglini CL, Mihalik JP, Shields EW, Tomasini NT. The National Football League Combine: performance differences between drafted and nondrafted players entering the 2004 and 2005 drafts. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(1):6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gains GL, Swedenhjelm AN, Mayhew JL, Bird HM, Houser JJ. Comparison of speed and agility performance of college football players on field turf and natural grass. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manoogian S, McNeely D, Duma S, Brolinson G, Greenwald R. Head acceleration is less than 10 percent of helmet acceleration in football impacts. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2006;42:383–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crisco JJ, Chu JJ, Greenwald RM. An algorithm for estimating acceleration magnitude and impact location using multiple nonorthogonal single-axis accelerometers. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126(6):849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowson S, Duma SM. Brain injury prediction: assessing the combined probability of concussion using linear and rotational head acceleration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(5):873–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowson S, Duma SM. Development of the STAR evaluation system for football helmets: integrating player head impact exposure and risk of concussion. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39(8):2130–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowson S, Duma SM, Beckwith JG, Chu JJ, Greenwald RM, Crisco JJ, et al. Rotational head kinematics in football impacts: an injury risk function for concussion. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.About Child & Teen BMI. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

- 37.Cheung PC, Cunningham SA, Narayan KM, Kramer MR. Childhood Obesity Incidence in the United States: A Systematic Review. Child Obes. 2016;12(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley ME, Kane JM, Espeland MA, Miller LE, Powers AK, Stitzel JD, et al. Head impact exposure measured in a single youth football team during practice drills. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;20(5):489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campolettano ET, Rowson S, Duma SM. Drill-specific head impact exposure in youth football practice. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tierney GJ, Denvir K, Farrell G, Simms CK. The Effect of Tackler Technique on Head Injury Assessment Risk in Elite Rugby Union. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(3):603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendricks S, den Hollander S, Tam N, Brown J, Lambert M. The relationships between rugby players’ tackle training attitudes and behaviour and their match tackle attitudes and behaviour. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2015;1(1):e000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asken BM, Brooke ZS, Stevens TC, Silvestri PG, Graham MJ, Jaffee MS, et al. Drill-Specific Head Impacts in Collegiate Football Practice: Implications for Reducing “Friendly Fire” Exposure. Ann Biomed Eng. 2018;doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-2088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiebe DJ, D’Alonzo BA, Harris R, Putukian M, Campbell-McGovern C. Association Between the Experimental Kickoff Rule and Concussion Rates in Ivy League Football. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2035–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]