Abstract

Purpose:

Care transitions between hospitals and skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are often associated with breakdowns in communication that may place patients at risk for adverse events. Less is known about how to address these issues in the context of busy patient care settings. We used process mapping to examine hospital discharge and SNF admission processes to identify opportunities for improvement.

Methods:

A quality improvement (QI) team worked with frontline staff to create a process map illustrating the sequence of events involved with hospital discharge and SNF admission. The project was completed at an academic medical center and two local SNFs in the northeastern United States. Participants represented the care management, medicine, nursing, admissions, and physical therapy services. The data informed hospital QI interventions seeking to improve the quality and safety of hospital-SNF transfers and reduce unplanned hospital readmissions.

Results:

The final process map highlighted numerous activities that need to be coordinated between care teams, including the time-sensitive exchange of clinical and administrative information. Participants shared insights about how care teams reach critical decisions about patient disposition and post-acute care utilization.

Conclusions:

Process mapping highlighted specific opportunities for improving communication between care teams. Participants advocated for earlier assessments of patients’ functional status and support systems, including reliable at-home services. They also reasoned that improved communication would help patients and providers reach decisions together, coordinate work efforts, and better prepare for hospital discharge and SNF admission. This information can be used to improve patient care transitions between hospitals and SNFs.

Keywords: care transition, hospital medicine, skilled nursing facility, process mapping, quality improvement, health services research, healthcare, evaluation, quality improvement

One in five Medicare fee-for-service patients is discharged to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) following hospitalization for acute medical illness (1). These patients are older and sicker than patients discharged home (2), and face increased risks of clinical deterioration and functional decline (3–5). Previous research has identified repeated breakdowns in communication and patient care during the transfer process (3, 6–8), leading to calls for quality improvement (QI) efforts that can enhance patient safety and reduce the rate of unplanned hospital readmissions (6, 9–11).

In this study, we used process mapping to closely examine the work involved with discharging patients from acute care hospitals and admitting them to SNFs. Process mapping is an improvement method that analyzes the interactions among individuals, groups, and systems (12, 13). Participants who have direct experience with the process of interest describe the steps they take to complete an activity. That information is compiled into an illustration displaying the involved tasks, parties, and decisions as a sequence of events. Process mapping is collaborative, participatory, and serves as a powerful tool for identifying risks and fostering change (12–14).

Our goal was to identify barriers to effective communication and patient safety practices inherent within the multiple workflows used to discharge patients from acute care hospitals to SNFs. The information can be used to identify specific opportunities for improvement efforts between care teams. It may also inform applications of this method to other complex processes, particularly in busy healthcare settings.

Methods

This project was conducted through a hospital-based patient safety learning laboratory funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (15). The Institutional Review Board at the center reviewed and exempted this project as QI.

Team members included the principal investigator, the project director, a research associate, and a certified QI consultant. The consultant had extensive experience in hospital-based process improvement and clinical care. Hospital study units included general medicine services at an urban, northeastern academic medical center. SNF study units included a suburban for-profit facility and an urban non-profit facility that were among the top volume recipients of patients discharged from the hospital for post-acute care. This criterion assured that the SNF providers were experienced in receiving patients from the study hospital.

The research associate worked with study unit supervisors to invite employees to participate in 30-minute process mapping sessions. Some supervisors extended the invitation to all staff while others recommended specific people based on their interests in QI efforts or experiences with the transfer process. The sessions were held on-site during work hours and did not disrupt patient care. The consultant facilitated all sessions. Participation was voluntary and did not affect relationships with the hospital, SNF, or center. Data were aggregated to protect confidentiality.

We completed seven process mapping sessions over a six-month period. Participants included frontline staff representing care management, medicine, nursing, admissions, and physical therapy (Table 1). During each session, the consultant asked participants to walk through a patient transfer, prompting them with questions to elicit specific details. For example, if a hospital participant said they asked a family for facility preferences, the consultant would follow up with questions about how they asked (i.e. in person, on the telephone), when they asked (i.e. at what point during the hospital stay), and what they asked (i.e. do they say ‘facility preferences’ or do they use other terms). The consultant sketched the responses onto an oversized pad while another team member took notes. After each session, the consultant organized the information into a draft process map (Microsoft Excel 2016) and held a debriefing meeting with the research associate.

Table 1:

Process Mapping Sessions

| Session | Unit Type | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hospital | Care management and transitional care coordination |

| 2 | Hospital | Care management and transitional care coordination |

| 3 | Hospital | Advanced practice providers, nursing |

| 4 | SNF | Admissions and frontline staff |

| 5 | SNF | Admissions and frontline staff |

| 6 | Hospital | Residents and nursing |

| 7 | Hospital | Physical therapy |

Draft maps were emailed to participants for review. The consultant completed the revisions and compiled the separate maps into one, comprehensive diagram; the research associate used Microsoft Visio (2013) to create a printer-friendly version for this report.

Results

Transfer Tasks

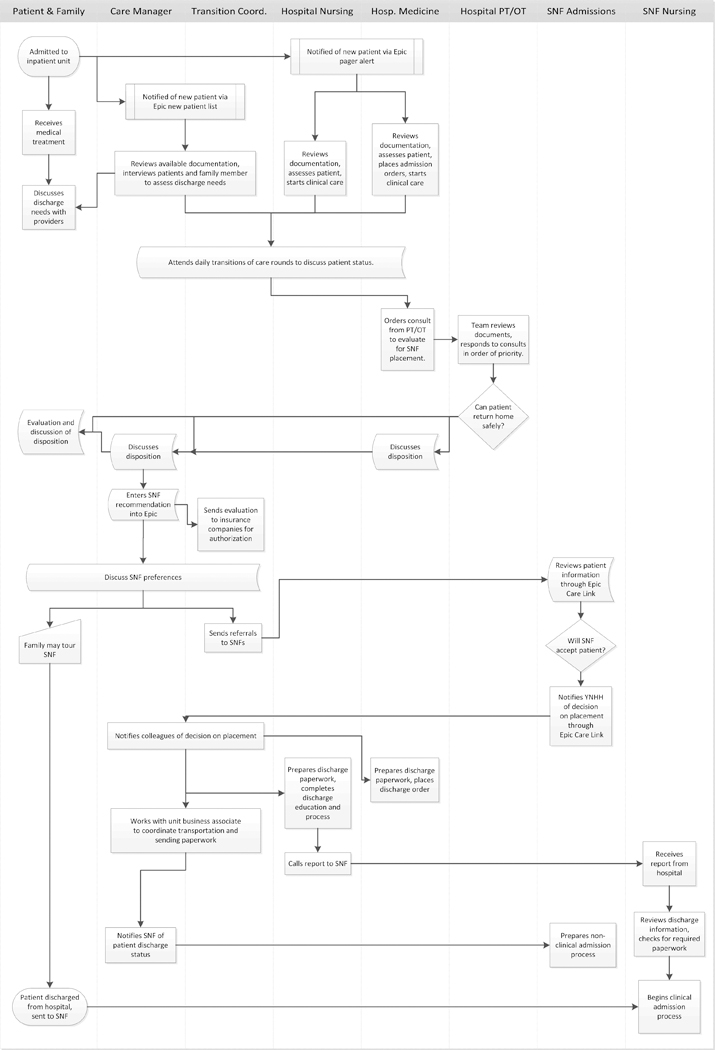

The final process map illustrated 34 discrete steps needed to transfer patients from the hospital to the SNF (Figure 1). The work included performing clinical, nursing, and specialty assessments; engaging patients and caregivers in care planning discussions; and managing orders, referrals, and authorizations. There was considerable variation in the time and effort needed for each task. For example, writing a strong hospital discharge summary required substantial time and concentration, whereas transfer reports were quickly completed through a series of checkboxes. Further, these activities are completed amidst participants’ other responsibilities, including caring for other patients.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the process of transferring a patient from the hospital to the skilled nursing facility (SNF)

Decisions to Send and Accept Patients to SNFs

The process map contained two pivotal decisions points. First, hospital care teams considered whether the patient could return home safely. While this decision was informed by several factors, including clinical status and access to a reliable support system, participants singled out the physical therapy evaluation as the most influential. This evaluation assesses patients’ functional status, as well as the physical structures and resources available within their homes.

The second decision belongs to SNF care teams, as they considered whether to accept the patient into their facilities. SNF participants reported weighing several factors, including the current facility census and the referred patient’s rehabilitation potential, needs for specialized medications or treatments, and payor source.

Participants described the conflicts that emerged during these decisions. Hospital participants recounted cases where the physical therapy evaluation was used to resolve disagreements among patients, caregivers, and clinicians, with each party trying to sway the physical therapists towards a specific disposition. SNF participants were vigilant towards rejecting referrals for patients with extensive or costly care needs. They argued that these placements were burdensome and could create unsafe situations for patients and SNF providers.

Coordination through Communication

Throughout the transfer process, participants updated and shared information using a variety of formats, including in-person meetings, telephone calls, faxes, and the hospital electronic health record (EHR). They relied on this information to coordinate parallel tasks and efficiently manage their work. Unlike hospital providers, SNF providers were less likely to have direct contact with patients and caregivers before accepting the patient. They relied more heavily on EHR searches, hospital documentation, and exchanges with hospital staff for information.

Any lapse in communication could easily derail the transfer process. The SNF referral process provides a relevant example. The hospital transition coordinator sends referral requests to the patient’s preferred SNFs. For a patient with private insurance, the request will include the physical therapy evaluation and insurance authorization. Patients with acceptance offers need to confirm their selections so the care teams can prepare for hospital discharge and SNF admission. However, if none of the facilities respond with an available bed, the patient remains hospitalized and the transition coordinator needs to begin the process again, casting a wider net until a placement is secured. If the search takes more than three business days, the physical therapy evaluation and insurance authorization expire, requiring the physical therapists to renew the evaluation and the transition coordinator to obtain another insurance authorization while the care manager continues to monitor the plan of care. This scenario was more likely to occur among complex patients with high care needs.

Discussion

We used process mapping, a collaborative improvement method, to identify opportunities to improve the quality and safety of care transitions between the hospital and SNFs. This step-by-step examination of the hospital discharge and SNF admission processes provided important insight into the work required to complete a transfer and care teams’ different approaches to decision-making. An important finding is the fundamental difference between how care teams at hospitals and SNFs approached patient disposition. Hospital participants framed the decision around whether the patient could return home safely once hospitalization for acute medical illness was no longer required (16, 17). The choice to utilize a SNF was often not made until later in the patient’s stay, which contributed to a pressure to quickly secure a facility placement and a skepticism among SNF participants about the appropriateness of patients for lower levels of care.

Process mapping also provided a venue for frontline staff to suggest their ideas for improvement. Hospital participants suggested that earlier communication with physical therapy could minimize rush requests and improve consult response time. Several added that this preventative approach could ultimately facilitate more discharges home, as patients with mobility plans may be less prone to deconditioning during the hospital stay (18). SNF participants felt that frank conversations about post-acute care options earlier in the hospitalization would give patients and caregivers time to consider their options and tour different facilities. They eagerly shared relevant policies and procedures that might have been unfamiliar to hospital staff.

Using process mapping helped our QI team understand the work required to transfer hospitalized patients to SNFs. The findings directly informed several local improvement initiatives at the host hospital, including the implementation of a warm handoff between clinicians at the time of hospital discharge (19). This initiative sought to foster direct communication between physicians and advanced practice providers, a gap which was evident on the process map.

Limitations

This project was completed at a single center, which may limit generalizability. The consultant was employed by the hospital and known to some of the participants, which could have led to social desirability bias. The participant selection process may have introduced bias as well, as participants who volunteered to attend sessions may have held stronger opinions than their colleagues. The process map does not include representation from hospital consult services that were electively referred in select cases, including social work and palliative care. It also does not represent the patient perspective or calculate timestamps.

Conclusion

We used process mapping to identify opportunities to improve care transitions from the hospital to the SNF, including reconciling different approaches to care planning. This method also provided an opportunity for participants to advocate for change, including earlier assessments of patients’ functional status and support systems, as well as improved communication to help patients and providers prepare for a safe transfer.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the participants for their openness and their commitment to quality improvement and patient safety.

Funding Source: Data were collected through the Yale Center for Healthcare Innovation, Redesign and Learning (CHIRAL, #P30HS023554–01). This research was supported by a grant (#P30HS023554–01) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and receives support from Yale New Haven Hospital and the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these organizations.

Footnotes

Ms. Campbell Britton, Ms. Petersen-Pickett, and Ms. Hodshon have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Chaudhry serves as a paid consultant for the CVS Caremark State of Connecticut Clinical Pharmacy Program.

References

- 1.Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2019 March 2019. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and Hospitalization Characteristics Associated With Increased Postacute Care Facility Discharges From US Hospitals. Medical Care. 2015;53(6):492–500. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Curtis LH, Dai D, Masoudi FA, et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):293–300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959171 PubMed PMID: ; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dombrowski W, Yoos JL, Neufeld R, Tarshish CY. Factors predicting rehospitalization of elderly patients in a postacute skilled nursing facility rehabilitation program. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2012;93(10):1808–13. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The Revolving Door Of Rehospitalization From Skilled Nursing Facilities. Health Affairs. 2010;29(1):57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King BJ, Gilmore‐Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, Polnaszek BE, Bowers BJ, Kind AJH. The Consequences of Poor Communication During Transitions from Hospital to Skilled Nursing Facility: A Qualitative Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(7):1095–102. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah F, Burack O, Boockvar KS. Perceived Barriers to Communication Between Hospital and Nursing Home at Time of Patient Transfer. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2010;11(4):239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toles M, Young HM, Ouslander J. Improving care transitions in nursing homes. Generations. 2012;36(4):78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, Min SJ, Levy C, Prochazka AV, et al. Hospital Readmission From Post-Acute Care Facilities: Risk Factors, Timing, and Outcomes. JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION. 2016;17(3):249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilmore‐Bykovskyi AL, Roberts TJ, King BJ, Kennelty KA, Kind AJ. Transitions from Hospitals to Skilled Nursing Facilities for Persons with Dementia: A Challenging Convergence of Patient and System-Level Needs. The Gerontologist. 2016;00(00):1–13. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouslander JG, Naharci I, Engstrom G, Shutes J, Wolf DG, Alpert G, et al. Root Cause Analyses of Transfers of Skilled Nursing Facility Patients to Acute Hospitals: Lessons Learned for Reducing Unnecessary Hospitalizations. JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION. 2016;17(3):256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JK, Farnan J, Barach P, Hesselink G, Wollersheim HC, Pijnenborg L, et al. Searching for the missing pieces between the hospital and primary care: mapping the patient process during care transitions. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2012;21(1):i97–i105. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2010;341(aug13 1):c4078-c. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin N, Rodstein J, Burke MA, Martin NA. Demystifying Process Mapping: A Key Step in Neurosurgical Quality Improvement Initiatives. Neurosurgery. 2014;75(2):99–109. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Associations between attending physician workload, teaching effectiveness, and patient safety. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Britton MC, Ouellet GM, Minges KE, Gawel M, Hodshon B, Chaudhry SI. Care Transitions Between Hospitals and Skilled Nursing Facilities: Perspectives of Sending and Receiving Providers. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2017;43(11):565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke RE, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, Ayele R, Lippmann B, Cumbler E, et al. How Hospital Clinicians Select Patients for Skilled Nursing Facilities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2017;65(11):2466–72. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyer EH, Friedman M, Lavezza A, Wagner-Kosmakos K, Lewis-Cherry R, Skolnik JL, et al. Promoting Mobility and Reducing Length of Stay in Hospitalized General Medicine Patients: A Quality-Improvement Project. JOURNAL OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE. 2016;11(5):341–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell Britton M, Hodshon B, Chaudhry SI. Implementing a Warm Handoff Between Hospital and Skilled Nursing Facility Clinicians. Journal of Patient Safety. 9000;Publish Ahead of Print. doi: 10.1097/pts.0000000000000529 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]