Abstract

The femoral bifurcation is typically composed of a common femoral artery that bifurcates into the superficial (SFA) and deep (DFA) femoral arteries, with the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA) branching distal to the origin of the DFA. We report a unique case of a 22-yr-old woman with a femoral “trifurcation,” where the origin of the LCFA coincides with the origin of the DFA, resulting in a true three-way branching of the common femoral artery. We characterized the complex hemodynamics of the trifurcation region with ultrasound vector flow imaging at rest, and during 80 mmHg cuff compression of the calf to induce greater oscillatory blood flow. At rest, a clear trifurcation is observed with color Doppler imaging, while vector flow imaging further revealed a large area of flow circulation proximal to the LCFA and DFA. Cuff compression reduced SFA blood flow to 0 cm3/min, characterized by almost constant retrograde blood flow throughout diastole. When visualized with vector flow imaging, diastolic retrograde blood flow from the SFA appeared to reperfuse the DFA and LCFA during late systole, eliminating the retrograde flow component and providing a secondary source of anterograde blood flow to the thigh. In a rare case of a femoral trifurcation, we demonstrate blood recirculation patterns at rest, as well as collateral retrograde blood flow redistribution during lower limb compression. While it is unknown whether these trifurcation findings extend to typical bifurcations, it is evident that advanced methods of blood flow characterization are necessary to visualize and study complex vascular regions.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A femoral “trifurcation” is observed when the lateral circumflex femoral artery has an atypical proximal origin, branching at the same level as the superficial and deep femoral arteries. Ultrasound vector flow imaging at 750 fps was able to reveal substantial blood recirculation within the trifurcation at rest, as well as unique redistribution of blood flow between downstream branches during external cuff manipulation of retrograde flow, indicating novel ways in which diastolic blood flow is controlled.

Keywords: arterial anatomy, blood flow, complex hemodynamics, external cuff compression, ultrasound, vector flow imaging

INTRODUCTION

In typical anatomy, the common femoral artery (CFA) bifurcates into the superficial femoral artery (SFA) and the deep femoral artery (DFA; also known as the profunda femoris artery) below the level of the midfemoral head. The SFA primarily feeds the knee (via the genicular arteries) and lower leg (via the popliteal, tibial, and peroneal arteries), while the DFA feeds the thigh through downstream branching first toward the femoral head by the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA), and then the deep thigh muscles by the perforating arterial branches. This vast downstream vascular network of the leg contributes to the unique biphasic (i.e., anterograde and retrograde) blood flow pattern in the femoral branches, and complex multidirectional blood flow patterns at the femoral bifurcation (1, 6). Given the proposed role for low, oscillatory shear stress to contribute to a proatherosclerotic vascular milieu (3), the study of hemodynamic complexity in this region may help explain the relatively high prevalence of plaque deposition (4) and local wall thickening (9) in the femoral bifurcation, even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Over the course of our recent investigations, we observed a noteworthy case of a femoral “trifurcation,” in which the LCFA branches at the intersection of the common and deep femoral arteries. To our knowledge, there is very low prevalence of a true trifurcation previously reported in the literature: single cadaver case studies from Greece (14) and India (11), and in 3 of 42 cadaver cases of black Kenyans (12). This specific trifurcation description does not fit into previously reported anatomical classifications of the LCFA origin (13, 15), and is considered a rare separate morphology by the above reports with possible implications for resting hemodynamics. While the anatomical description has been reported, the blood flow dynamics have never been quantified in vivo, which may have functional consequences for how blood traverses the femoral arterial tree.

In this Case Study in Physiology, we report incidental findings from a recent experiment in which we observed a femoral “trifurcation” at rest, and during experimental manipulation of retrograde blood flow in the SFA to induce highly complex hemodynamic behavior at the femoral branching point. While conventional ultrasound imaging is unable to quantify blood velocity within bifurcations due to nonlaminar blood flow, our laboratory has refined the vector flow imaging technique (5, 7) to visualize and quantify angle-independent blood velocity vectors at high frame rates (>1,000 fps) to better characterize multidirectional blood flow features (2, 17, 18). These emerging techniques are highly relevant to study complex hemodynamics in atherosclerotic-prone regions such as arterial bifurcations, as in the specific case of the femoral arterial branches.

METHODS

Case study.

We present data from a 22-yr-old Caucasian woman (height 1.6 m, body mass 65 kg) who volunteered for an ongoing study in our laboratory. The participant was in good health with no apparently clinical consequences of the anatomical variation. The study protocol was approved by the local research ethics board, and informed consent and permission to use these data in a case study format were received in writing from the participant. After 10 min of supine rest, ultrasound was performed at the CFA, SFA, DFA, and femoral bifurcation at rest, and during subsystolic 80 mmHg cuff occlusion of the lower leg. Imaging was performed on both the right and left sides.

Conventional Doppler ultrasound.

Conventional ultrasound imaging was performed with a 9–3 MHz linear array probe (Phillips iE33; Phillips Medical Systems, Andover, MA). At rest, and after 2 min of cuffing, 10-s B-mode images, color Doppler images, and single-gate pulsed Doppler spectrograms were acquired sequentially at the CFA, SFA, and DFA ~2–3 cm from the bifurcation to quantify conduit artery blood flow patterns. We were unable to capture LCFA blood velocities using pulsed wave Doppler. For single-gate Doppler data acquisitions, the angle of insonation was kept at 60° to limit velocity estimation errors, while the velocity sample gate was extended to the arterial walls >1 cm away from the bifurcation region. Arterial diameters were extracted from B-mode images, and the intensity-weight mean blood velocity (MBV) signal was extracted from the Doppler spectrogram, using commercial software (Measurements from Arterial Ultrasound Imaging; Hedgehog Medical, Waterloo, Canada). Blood flow was calculated as:

where d is arterial diameter; d and MBV are expressed in cm and cm/s, respectively.

High-frame rate ultrasound (HiFRUS) and vector flow imaging.

Research-grade ultrasound imaging was performed with a 13–3 MHz linear array probe (pitch: 0.245 mm; Esaote SL1543, Genova, Italy) connected to an open-platform ultrasound unit (USPlatform; US4US, Warsaw, Poland) for which the imaging sequences and data handling operations can be customized in a software programming environment (17). A two-angle (−10°, 10°) plane wave transmit sequence (5 MHz 2-cycle pulse) was used to acquire raw HiFRUS data for time-resolved flow vector estimation at a pulse repetition frequency of 6,000 Hz, allowing ~4 s of data capture per acquisition. Data sets were transferred to an offline server for parallel beamforming and signal processing in Matlab (R2016a; Mathworks, Natick, MA) (16, 17). To derive the flow vector at each pixel position in the vasculature, four unique transmit-receive angle pairs were used in the signal processing chain such that the cosθ correction factor in the Doppler equation can be eliminated to yield an angle-independent flow velocity estimate (18). Data regularization was applied to each angle pair’s Doppler frequency estimate that was used as input for flow vector computation, which served to suppress spurious or aliased Doppler frequency estimates. The final effective frame rate of vector flow images was 750 fps. Data was visualized using the vector projectile imaging algorithm, which dynamically renders flow paths through interframe position updates of color-coded projectiles representing the magnitude and direction of flow velocity vectors within a manually identified arterial wall boundary (16). Vector-based mean blood velocity magnitude was extracted from a manual region of interest extending across the full lumen diameter ~1 cm from the flow divider, keeping the bifurcation within the imaging view.

RESULTS

Anatomical description.

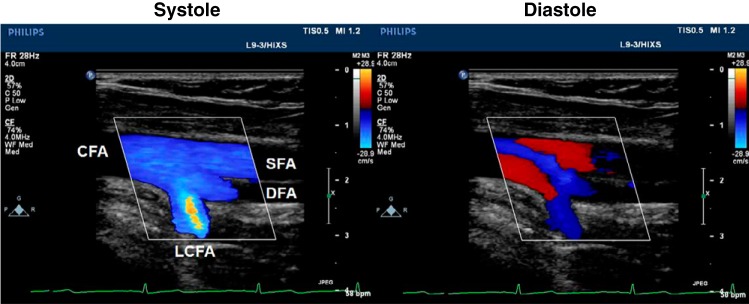

Trifurcations were observed at both the right and left femoral arteries, although only the right trifurcation was fully in-plane and is therefore the focus of this report. The origin of both the DFA and LCFA occur at the same level of the SFA, resulting in a true triple branching of the CFA (Fig. 1). The limitations of conventional color Doppler imaging are noted, as the deep orientation of the LCFA is not consistent with the single insonation angle used to delineate blood velocity magnitude and direction, resulting in aliased color information.

Fig. 1.

Color Doppler imaging of a femoral “trifurcation” in systole and diastole. The common femoral artery (CFA) branches into the superficial femoral artery (SFA), deep femoral artery (DFA), and lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA). Simultaneous bidirectional blood velocities can be observed in diastole with simplified color Doppler indicating the direction of blood either in the anterograde (blue) or retrograde (red) directions.

Hemodynamics at rest and during 80 mmHg cuff compression.

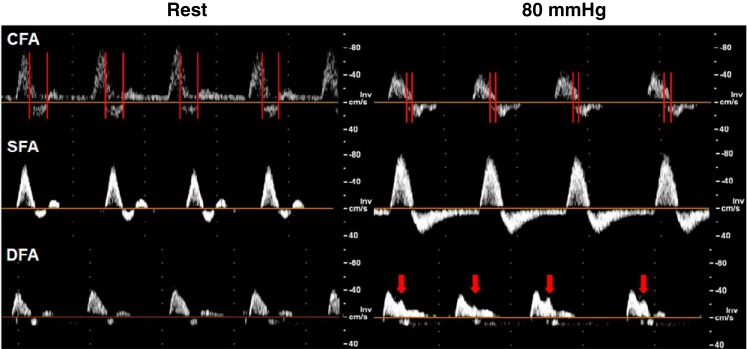

Conduit artery hemodynamics are presented in Table 1 with representative Doppler spectrograms presented in Fig. 2. Sub-systolic cuff occlusion of the right calf increased anterograde (Δ8.7 cm/s), and retrograde (Δ12.4 cm/s) peak blood velocity, and decreased blood flow to 0 cm3/min in the SFA, characterized by constant retrograde flow in diastole (Fig. 2). In comparison, the DFA exhibited a reduction in peak retrograde velocity, while CFA peak anterograde and mean blood velocity were reduced. The LCFA was unaffected by the cuff intervention.

Table 1.

Hemodynamic changes with application of lower limb cuff compression measured by conventional pulsed wave Doppler

| Variable | Rest | 80 mmHg |

|---|---|---|

| Common femoral artery | ||

| Mean blood velocity (cm/s) | 9.6 | 1.8 |

| Peak anterograde blood velocity (cm/s) | 47.1 | 28.5 |

| Peak retrograde blood velocity (cm/s) | −13.1 | −14.5 |

| Mean arterial diameter (mm) | 8.6 | 8.5 |

| Blood flow (cm3/min) | 332.5 | 61.0 |

| Superficial femoral artery | ||

| Mean blood velocity (cm/s) | 4.7 | 0.0 |

| Peak anterograde blood velocity (cm/s) | 38.9 | 47.6 |

| Peak retrograde blood velocity (cm/s) | −9.8 | −22.2 |

| Mean arterial diameter (mm) | 6.2 | 6.6 |

| Blood flow (cm3/min) | 84.8 | 0.0 |

| Deep femoral artery | ||

| Mean blood velocity (cm/s) | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Peak anterograde blood velocity (cm/s) | 26.7 | 25.7 |

| Peak retrograde blood velocity (cm/s) | −9.5 | −1.5 |

| Mean arterial diameter (mm) | 5.6 | 5.7 |

| Blood flow (cm3/min) | 57.4 | 60.8 |

| Lateral circumflex femoral artery* | ||

| Mean blood velocity (cm/s) | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| Peak anterograde blood velocity (cm/s) | 13.5 | 16.8 |

| Peak retrograde blood velocity (cm/s) | −2.5 | −1.1 |

| Mean arterial diameter (mm) | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Blood flow (cm3/min) | 21.9 | 26.9 |

Derived from vector flow data.

Fig. 2.

Doppler spectrogram of the common femoral artery (CFA), superficial femoral artery (SFA), and deep femoral artery (DFA) at rest and during 80 mmHg cuff occlusion. Red vertical bars identify periods of simultaneous overlap between anterograde and retrograde blood velocities. Red arrows indicate a late systolic anterograde peak.

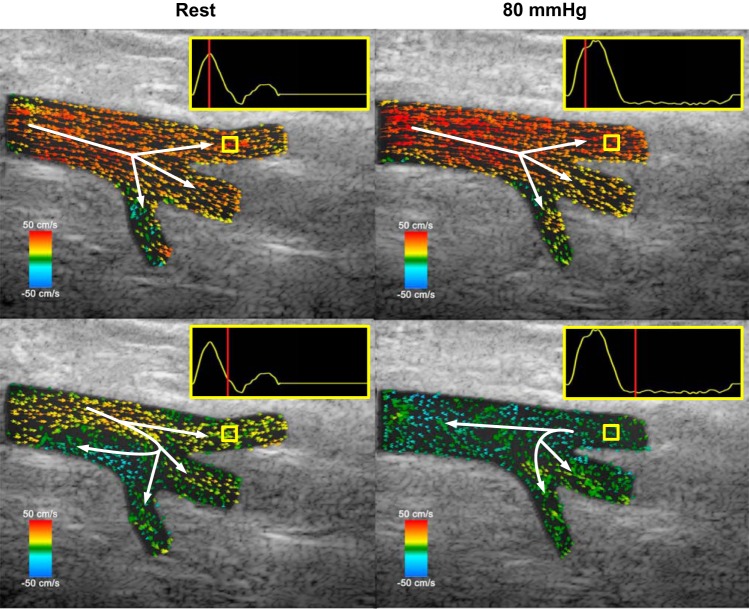

Vector flow imaging.

The results of our vector projectile imaging visualization of the femoral trifurcation are presented in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video S1 (available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8344004.v1). Visualizations are measured from one heart cycle at 750 fps, and played back at 25 fps over 16 s to appreciate the complexity of hemodynamic behavior during flow reversal and recirculation. Unlike color Doppler imaging, specific paths of blood velocity vectors can be noted. At rest, anterograde blood vectors are largely laminar through the CFA, SFA, and DFA, while vectors in the LCFA go deeper into the thigh. Flow reversal occurs nonuniformly in the main trunk, with flow recirculation first occurring proximal to the LCFA while anterograde flow through to the SFA is maintained. This bidirectional flow is also observed in the CFA Doppler spectrogram trace in Fig. 2, where the red vertical bars indicate simultaneous anterograde and retrograde velocities in the same sampling region, causing some error in average velocity measurement.

Fig. 3.

Representative vector flow images of a femoral trifurcation at rest and during 80 mmHg cuff compression of the lower leg. Velocity traces are extracted from the yellow region of interest in the superficial femoral artery. Top panels are extracted during systole, while bottom panels are extracted during flow recirculation points during diastole, with the corresponding phase of the cardiac cycle indicated by the red vertical line within the reference velocity trace. Scale bars refer to right (red) or left (blue) orientation of blood flow.

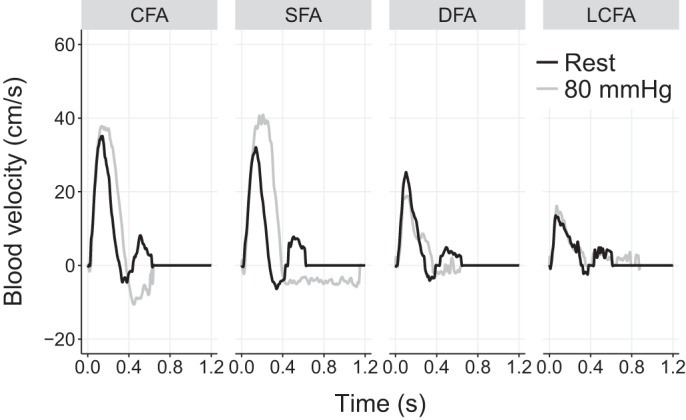

Vector flow patterns remained similar during cuff compression, albeit with changes in the timing and magnitude of the recirculation zone. Flow recirculation occurred in a similar area, although in a smaller region for a shorter period of time. However, the larger, sustained retrograde blood flow stream from the SFA created an unforeseen hemodynamic pattern, where the bulk of blood travels upwards in the CFA, but the streams proximal to the DFA and LCFA redirect in the lower half of the bifurcation and appear to further perfuse the DFA and LCFA even during early diastole when flow should be reversed. This trend is summarized in Fig. 4, which shows the mean flow velocity at each artery inlet between normal and cuffed conditions. Note that the plotted flow velocity values are derived from the corresponding flow vector estimates that are projected to the parallel axis of the vessel wall of the artery inlet segment. During 80 mmHg cuff occlusion, retrograde flow is reduced in the DFA and LCFA, and is replaced by periods of anterograde flow, most notably in the LCFA. This effect can also be observed in the pulsed-wave Doppler spectrogram (Fig. 2), where the DFA shows a secondary anterograde peak late in systole (~0.25 s into the cardiac cycle), consistent with the direction of blood vectors in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video S1.

Fig. 4.

Regional blood velocity traces of the common femoral artery (CFA), superficial femoral artery (SFA), deep femoral artery (DFA), and lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA), extracted simultaneously from the same cardiac cycle from flow vector estimates.

DISCUSSION

In this case study, we report complex hemodynamic behavior in a femoral “trifurcation,” a rare variant of a proximal origin of the LCFA, using an emerging ultrasound technique. Vector flow imaging revealed significant blood flow recirculation at rest, as well as collateral retrograde blood flow redistribution during lower limb compression. While it is unclear whether findings from this case study would also be replicated in more typical bifurcation anatomy, these results offer new scientific insight into both the study of complex hemodynamic environments, as well as interarterial communication in conduits that are typically thought of as isolated systems.

The multidirectional characteristics of femoral bifurcation hemodynamics have scarcely been investigated in the literature. While it is technically possible to use single-gate pulsed wave Doppler to assess velocity in the bifurcation, characterization is not possible due to nonuniform flow distributions across the width of the lumen. To our knowledge, only simulation work has been conducted to examine the complexity of femoral bifurcation hemodynamics, suggesting the presence of nonlaminar flow in this region (1, 6, 8). This is surprising as the femoral bifurcation is prone to plaque deposition, likely related to the exposure of turbulent blood flow or oscillatory wall shear stress at the branching point (4, 9). The presence of a trifurcation may complicate inferences made from these observations, which provides this case study a unique perspective on complex hemodynamics. Replication of these findings in a larger sample of typical bifurcations would help shed light on the novelty of these trifurcation hemodynamics, particularly whether the magnitude of blood flow recirculation and interarterial communication in downstream conduit arteries are reproducible observations.

While the HiFRUS-based vector flow imaging techniques used in this investigation are relatively novel to the physiological sciences, we demonstrate their potential to uncover relevant hemodynamic phenomena that cannot be investigated with conventional Doppler ultrasound. As this imaging technology is largely still in active development (7), our acquisition was restricted to a limited number of cardiac cycles to preserve the high frame rate (750 fps) nature of our data. We are unable to confirm interbeat variability that may have influenced our findings, although color Doppler images obtained from conventional ultrasound imaging suggests that zones of flow reversal are consistent with vector projectile imaging beat-to-beat, indicative of the stability of these hemodynamic patterns.

As this is a single case study, there are significant limitations to the inferences that can made from these data. At minimum, it should be noted that individual arterial anatomy may vary widely and is thought to largely dictate the presence and magnitude of flow phenomena, such as recirculation (10). For this reason, we are unable to directly compare the hemodynamic patterns of this femoral trifurcation with a randomly sampled femoral bifurcation, as even in typical anatomy, there would exist large interindividual differences in bifurcation flow patterns. This limitation is compounded by the planar nature of ultrasound, where we can only confidently visualize and quantify information in a narrow arterial longitudinal section. This limitation was noted in the participant’s left femoral trifurcation, in which we were unable to acquire all four femoral branches in the same imaging view. This likely also impacts the vector visualization in the LCFA, where it appears blood vectors originate at the vessel wall; in reality, this is likely due to slight tortuosity in vessel geometry. A related limitation of this technique is that we are unable to confirm whether 3D vortical flow also occurs out-of-plane in this region. While the femoral bifurcation region does not present with a bulb similar to the carotid sinus (16), the presence of blood flow recirculation suggests that out-of-plane motion occurs, requiring 3D/4D imaging to fully appreciate the complexity of the hemodynamic patterns.

In summary, we report a unique case of a femoral trifurcation characterized by a proximal origin of the LCFA. We observed flow recirculation at rest and collateral retrograde blood flow redistribution from the SFA to the DFA and LCFA during diastole during cuff manipulations. While inferences to typical bifurcations may be limited, this unique case of a femoral trifurcation offers interesting insight into how anatomical variability might impact complex hemodynamic patterns, which may be revealed with emerging noninvasive imaging techniques.

GRANTS

This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (PJT-153240), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2016-04042; CREATE-528202-2019), the Canada Foundations for Innovation (36138), an Ontario Early Researcher Award (ER16-12-186 to A. C. H. Yu) and a CIHR Post-doctoral Fellowship (MFE-152454 to J. S. Au).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.S.A., B.Y.S.Y., and A.C.H.Y. conceived and designed research; J.S.A. performed experiments; J.S.A. and B.Y.S.Y. analyzed data; J.S.A., B.Y.S.Y., and A.C.H.Y. interpreted results of experiments; J.S.A., B.Y.S.Y., and A.C.H.Y. prepared figures; J.S.A. drafted manuscript; J.S.A., B.Y.S.Y., and A.C.H.Y. edited and revised manuscript; J.S.A., B.Y.S.Y., and A.C.H.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiri MH, Keshavarzi A, Karimipour A, Bahiraei M, Goodarzi M, Esfahani JA. A 3-D numerical simulation of non-Newtonian blood flow through femoral artery bifurcation with a moderate arteriosclerosis: investigating Newtonian/non-Newtonian flow and its effects on elastic vessel walls. Heat Mass Transf 55: 2037–2047, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00231-019-02583-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au J, Hughson R, Yu A. Riding the plane wave: considerations for in vivo study designs employing high frame rate ultrasound. Appl Sci (Basel) 8: 286, 2018. doi: 10.3390/app8020286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, van der Baan A, Grosveld F, Daemen MJAP, Krams R, de Crom R. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation 113: 2744–2753, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidsson L, Fagerberg B, Bergström G, Schmidt C. Ultrasound-assessed plaque occurrence in the carotid and femoral arteries are independent predictors of cardiovascular events in middle-aged men during 10 years of follow-up. Atherosclerosis 209: 469–473, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goddi A, Fanizza M, Bortolotto C, Raciti MV, Fiorina I, He X, Du Y, Calliada F. Vector flow imaging techniques: An innovative ultrasonographic technique for the study of blood flow. J Clin Ultrasound 45: 582–588, 2017. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javadzadegan A, Lotfi A, Simmons A, Barber T. Haemodynamic analysis of femoral artery bifurcation models under different physiological flow waveforms. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 19: 1143–1153, 2016. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2015.1113406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen JA, Nikolov SI, Yu ACH, Garcia D. Ultrasound vector flow imaging. II. Parallel systems. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 63: 1722–1732, 2016. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2016.2598180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YH, Kim JE, Ito Y, Shih AM, Brott B, Anayiotos A. Hemodynamic analysis of a compliant femoral artery bifurcation model using a fluid structure interaction framework. Ann Biomed Eng 36: 1753–1763, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornet L, Hoeks APG, Lambregts J, Reneman RS. In the femoral artery bifurcation, differences in mean wall shear stress within subjects are associated with different intima-media thicknesses. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 2933–2939, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.12.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perktold K, Resch M. Numerical flow studies in human carotid artery bifurcations: basic discussion of the geometric factor in atherogenesis. J Biomed Eng 12: 111–123, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(90)90131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savithri P. A rare variation of trifurcation of right femoral artery. Int J Anat Var 6: 4–6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinkeet SR, Ogeng’o JA, Elbusaidy H, Olabu BO, Irungu MW. Variant origin of the lateral circumflex femoral artery in a black Kenyan population. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 71: 15–18, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomaszewski KA, Vikse J, Henry BM, Roy J, Pękala PA, Svensen M, Guay D, Saganiak K, Walocha JA. The variable origin of the lateral circumflex femoral artery: a meta-analysis and proposal for a new classification system. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 76: 157–167, 2017. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2016.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troupis T, Michalinos A, Markos L, Samolis A, Tsakotos G, Dimitroulis D, Venieratos D, Skandalakis P. “Trifurcation” of femoral artery. Artery Res 7: 106–108, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.artres.2012.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vuksanović-Božarić A, Abramović M, Vučković L, Golubović M, Vukčević B, Radunović M. Clinical significance of understanding lateral and medial circumflex femoral artery origin variability. Anat Sci Int 93: 449–455, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s12565-018-0434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yiu BYS, Lai SSM, Yu ACH. Vector projectile imaging: time-resolved dynamic visualization of complex flow patterns. Ultrasound Med Biol 40: 2295–2309, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yiu BYS, Walczak M, Lewandowski M, Yu ACH. Live ultrasound color encoded speckle imaging platform for real-time complex flow visualization in vivo. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 66: 656–668, 2019. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2019.2892731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yiu BYS, Yu ACH. Least-squares multi-angle Doppler estimators for plane-wave vector flow imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 63: 1733–1744, 2016. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2016.2582514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]